Strategic Assessment

- Book: The United Arab Emirates: The Unique Story of an Arab Federation

- By: Uzi Rabi

- Publisher: Resling Publishing

- Year: 2025

- pp: 319

In the early 1980s Yuval Steinitz was an undergraduate philosophy student at the Hebrew University. I know something about those years, since one of the students in the department was my older brother, whose stories from that era are very familiar to me. The teachers included such giants as Professors Nathan Rotenstreich, Yeshayahu Leibowitz and Yirmiyahu Yovel. But as my brother used to tell us, Steinitz did not come to Jerusalem to discuss philosophy with them, but rather with the person whose writings they taught. Prof. Yovel in particular, according to my brother, would sometimes lose his patience and remind the enthusiastic student Steinitz that the debate in the classroom was over the interpretation of Spinoza, and not with Spinoza himself.

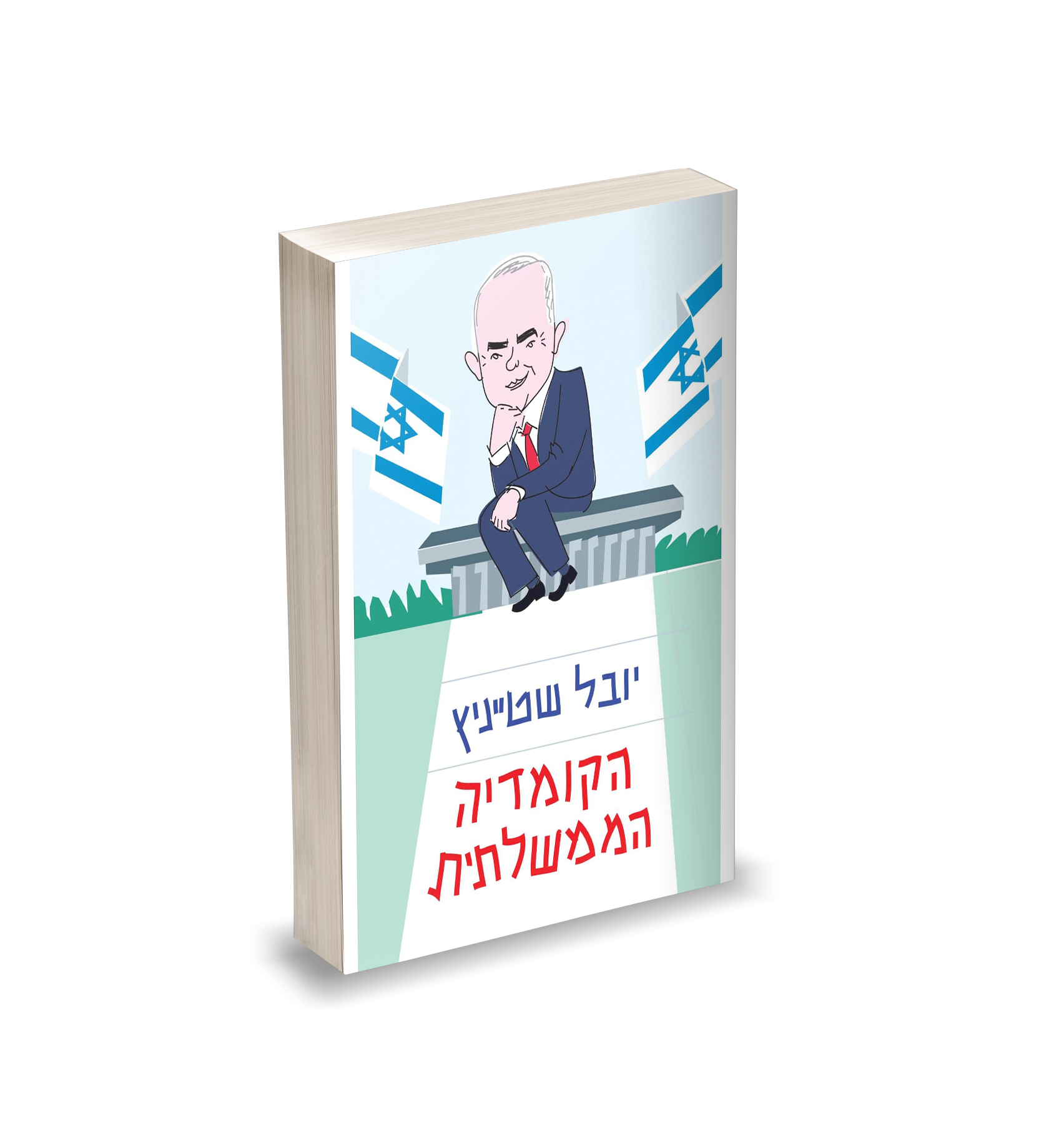

I recalled this old story as soon as I read the blurb on the cover of Steinitz’s latest book, The Government Comedy. The author, it states, is “the only philosopher in history who has served as the Minister of Finance, the Minister of Energy, a member of the Cabinet, and chairman of the Foreign Affairs & Defense Committee of any country [… He is] the person who was responsible for the invention of the two-year budget, our acceptance by the OECD, the exposure of the nuclear reactor in Syria, the investigation of the intelligence failures in Iraq and Libya, and ‘the Russo-American plan’ to dismantle chemical weapons in Syria.”

On the front cover, next to the title that of course echoes Dante Alighieri, there is a drawing of Steinitz sitting on top of the Knesset building in the pose of Auguste Rodin’s statue, The Thinker. Steinitz, whose book is replete with quotes of media headlines that complimented him and disagreements with those that were less complimentary, apparently remains in his own eyes someone whose proper place is among the giants of the human spirit, as befitting one who over forty years ago was already arguing with Spinoza.

This article is not a literary critique and suffice it to say that the slightly obsessional need of the thinker Yuval Steinitz to assert his own value rather casts a shadow over the quality of the writing. Steinitz knows how to write, as anyone who has read his works on philosophical matters will testify: Not only The Invitation to Philosophy, which the author constantly reminds us is “the top-selling book on philosophy in the history of Israel,” and about which he naturally tells us that “many of the journalists who could be found in the corridors of the Knesset at that time complimented me on” (since as we know there is nothing that parliamentary correspondents spend more time reading than books of popular philosophy), but also his excellent foreword to the Israeli edition of The Open Society by Karl Popper. Apparently this trait of his finds expression mainly when he writes about others.

Nor will I engage with the glories that Steinitz ascribes to the two-year budget, which is remembered by many as a largely political exercise from the Benjamin Netanyahu school of thinking rather than a groundbreaking macroeconomic innovation, or “my part in the amazing rescue of Israel from the global economic crisis that struck the whole world in the years 2009-2012” (p. 10). It will suffice to mention that the crisis began in 2007, reached its peak in September 2008, and if we can believe Wikipedia, “from the middle of 2009 the first signs of global economic recovery could be perceived.” For most of that time the government of Israel was led by Ehud Olmert; in my opinion, the then Finance Minister Roni Bar-On and senior members of his Ministry, as well as the solid foundations of the Israeli economy, can certainly claim much of the credit for the way Israel weathered the crisis.

Our interest lies in matters of national security, and therefore the emphasis here will be on the events that Steinitz describes from his days as chairman of the Foreign Affairs & Defense Committee in the years 2003-2006 and as a member of the cabinet. According to the picture painted by Steinetz, during his tenure the Committee was never afraid to confront the security establishment, and he himself never hesitated to clash with Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, with Defense Minister Shaul Mofaz, and above all, with Chief of Staff Moshe Ya’alon. A number of points that require clarification arise from his account.

Firstly, his main accomplice was Haim Ramon, at that time a member of the opposition. This is an important point with respect to the functioning of the Committee, in contrast to most of the Knesset committees: At its best, the Foreign Affairs & Defense Committee and its sub-committees are the only places in the Knesset where independent positions are taken, irrespective of alignment to a particular side of the House. This is very rare in the Knesset, which is one of the weakest parliaments in the democratic world, and is dominated to an extreme and doubtfully constitutional extent by the government. During Steinitz’s years as chairman this characteristic was indeed noticeable, as in the six years when I had the privilege of serving on the Committee (Omer Bar-Lev and I, both members of the opposition, headed two of the main sub-committees, with the full support and backing of the chairman Avi Dichter).

Since 2019 this feature has disappeared completely, and with it the function of the Foreign Affairs & Defense Committee in general, which today is a circus empty of content, like the Knesset as a whole. Benjamin Netanyahu’s attitude towards it is the same as his attitude to other organs of government: Contempt for any trace of separation of powers, absolute disdain for anything done by the Committee (or any other committees for that matter, or the IDF or the GSS), which can be seen in the reckless trading of senior positions for short-term political and personal needs, the parachuting in of candidates lacking any abilities, and satisfaction with the resulting situation—absolute inability to function.

From experience I can testify that Netanyahu, in times far better than today, failed to recognize the work of the Committee, was repeatedly surprised by its members’ knowledge (which is far broader and deeper than that of any member of the government, including the Minister of Defense, because of the wide range of areas covered by the Committee and because they have time to learn), and showed unwillingness to reveal to it things that were almost trivial in comparison to the material frequently presented to the sub-committees. In general, the Prime Minister met mostly with the Intelligence Sub-Committee; and at these meetings, from which not even a shred of intelligence ever leaked, Netanyahu had the habit of saying that he would present certain things “at the sub-committee.” All we could do was remind him that this was the sub-committee and there was no other below it.

Steinitz, who had no political power of his own and was in fact appointed to each of his senior jobs precisely because he was no political threat to Netanyahu, does not mention or even hint at any of this or other dubious actions of the Prime Minister in his book. Perhaps this represents a proper degree of gratitude to the man who enabled him to occupy these and other positions; yet given the time and context in which this book is being published, it is hard to find in it the type of courage of which he boasts.

Contrary to other important committees in the Knesset (and again, this refers to a “normal” Knesset, and not what we’ve had here for the past six years), the main responsibility of the Foreign Affairs & Defense Committee is supervision. It rarely legislates, and when it does legislate it is subject to the same constraints of coalition-opposition, as is apparent from the twists and turns of the conscription legislation over the past two years. This was also the situation in days gone by: Most of the practical and forward-looking recommendations of Steinitz’s investigation into intelligence failures have not yet been implemented. These include transforming Unit 8200 into a SIGINT authority outside the IDF; appointing a Secretary of Intelligence with the same status as the Military Secretary to the Prime Minister; establishing a ministerial committee for intelligence; passing the intelligence law; and reforming the intelligence community structure.

The central event of Steinitz’s time on the Foreign Affairs & Defense Committee was indeed his decision to set up an inquiry, in the framework of the intelligence sub-committee, to investigate a “reverse intelligence failure”; not the absence of a warning of an enemy attack, as happened in October 1973 and October 2023, but inflated warning of Iraq’s unconventional weapons capabilities, which led to rash decisions such as calling up the reserves and the purchase of unnecessary vaccinations against biological weapons, which the Iraqis did not have. Another failure of the intelligence system was that it knew nothing of the nuclear project (and the plan to make weapons of mass destruction in general) in Libya, which had reached an advanced stage, and was discovered by foreign intelligence services and dismantled in agreement with the United States and Britain in 2003.

The inquiry was an unprecedented step, and the response of the system—particularly Ya’alon—was Pavlovian: Opposition, refusal to cooperate, and defamation of the sub-committee report after its publication. Steinitz, who throughout the book enjoys describing himself as the child who angers everyone by stubbornly declaring that the king is naked, describes this whole episode with undisguised glee.

This inquiry led to what he is especially proud of: According to his version, during the sub-committee’s investigation of intelligence failures in Iraq, the suggestion arose that the Assad regime in Syria was setting up a secret nuclear project. The Committee was not content with merely raising this possibility, which was rejected and mocked by senior members of the intelligence community, but also issued a warning letter to Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, stating that “there is a high probability that Syria has a military nuclear project” (p.80), and even held further discussions on the matter.

The reactor in Deir ez-Zor, whose existence was finally confirmed in early 2007, was attacked and destroyed by the IAF in September of that year. Steinitz rightly takes the credit for himself and the sub-committee for their initial warning of its possible existence, which he claims also made Mossad head Meir Dagan divert efforts to this matter. This was contrary to the confident assurances by the heads of Intelligence Aharon Ze’evi-Farkash and Amos Yadlin, that Israel’s intelligence coverage of Syria was optimal, and therefore there was no possibility that such a strategic project could exist without Israel’s knowledge.

This was indeed an important contribution, but to express it in the words “the sub-committee understood what the intelligence community did not understand” is in my opinion the wrong way to frame the role of parliamentary supervision in general. The point is not that Steinitz was right and Intelligence was wrong; the point is that the sub-committee, which had been given no facts indicating the existence of a Syrian nuclear project, did what a civilian and external body ought to do: it brought a different perspective.

Steinitz describes the thinking that prompted this alternative perspective. Apparently it was based on an analysis of Syria’s situation, on its declared objective since the days of Assad senior to reach a “strategic balance” with Israel, and on the fact that, as he puts it, “in serious intelligence work it is permitted and even necessary to raise hypotheses – just as in the natural sciences” (p. 77).

This is an important statement in relation to the allegation that in Iraq the situation was reversed—the intelligence system was convinced of the existence of a nuclear project and supported the CIA’s false claim in this respect (a claim that derived, as we now know, from pressure exerted by President Bush and even more so by Vice President Richard Cheney), and the justification for the disastrous American invasion of Iraq. In Syria too, by the way, the statements from Hafez al-Assad on the need for strategic balance were first heard back in 1982, after the defeat of the Syrian Air Force and its array of ground-to-air missiles by the Israeli Air Force in June of that year, while the Deir ez-Zor project was launched no less than 18 years later. Had Steinitz insisted on his hypothesis in 1995, for example, and had similar efforts been made to examine it at that time, the Committee would have been accused of baseless alarmism and wasting the limited resources of the intelligence community. Yet still, in my view, the Committee would have been doing its job properly, since its function is not to know what the intelligence system does not know, but to identify options that have a conceptual basis requiring examination.

At the same time, there is a delicate balance between alarmism—repeatedly mentioning possible threats, when the purpose in many cases is to say “I told you so” when one of them materializes—and the essential indication of failures in readiness that must be rectified. Thus an article that Steinitz wrote in 1998 with the title “When the Palestinian army invades central Israel” becomes a concrete warning of what happened 25 years later. The problem with alarmism is that it makes any concrete discussion of priorities irrelevant: We have to be ready for every threat, at all times. That may sound reasonable to an Israeli who lived through October 7, 2023, but it’s not a way to administer life, a country, an economy and a society.

“Supervision,” contrary perhaps to what is implied in Steinitz’s book, is not necessarily and certainly not only about arguing with the system. At their best, sub-committees have an essential and unique role precisely because their discussions, unlike cabinet discussions, do not culminate in executive decisions, and just as importantly, because there are no leaks from them. They thereby provide a forum for military personnel and other organizations to engage with civilian thinking in a safe space, and this influences their thinking much more than the wrangling in the cabinet.

The confrontational position that Steinitz describes is far preferable to what he himself calls a “passive House of Lords” in the Foreign Affairs & Defense Committee, when former members of the system meet to hear gossip from their successors and to encourage them, but this attitude could also lead to a situation in which the function of the sub-committees appears to be limited to complaining and quarreling with senior officials. It is important to allow justified criticism to coexist with constructive debate. From my experience, I can say that when Dichter was chairman of the Committee in the 20th Knesset (the last time Israel had a functioning Knesset), this balance was maintained. Today of course none of this is relevant.

Elsewhere in the “Government Comedy” Steinitz relates to his time as a member of the cabinet. Many reports from the State Comptroller and other bodies have documented the weakness of the cabinet, which in the Israeli system is the nearest thing to the “supreme commander” of the military, but which almost by definition consists of people whose knowledge is scant, who spend little time on learning, and whose positions are largely dictated by political considerations. Similar things have been said about the function of the National Security Council, which was set up to optimize the process of discussion and decision making on political and defense matters, and about the structural weakness of the Defense Minister’s staff, to which the army is legally subordinate.

Steinitz’s narrative of his time in the cabinet is evidence of this, although he is in fact principally engaged with the story of how he himself, as “Don Quixote, about to storm the windmills of the Air Force completely alone” (p. 298), blocked the Air Force’s intention to acquire a second fleet of F-35 planes and brought about the decision to limit the procurement of additional aircraft to only 14. Here I won’t go into the actual discussion, which is very familiar to me. Suffice to say that ultimately the Air Force received what it wanted, down to the last plane, and more.

The real story that Steinitz is telling here is not about his legitimate position, but about the fact that the cabinet discussions are, in the words of Avigdor Lieberman to the State Comptroller, “no more than ministers letting off steam.” Prime ministers and army officers treat them as a political ritual they have to get through—and in recent years, mainly as a public “hazing” for the heads of security organizations, which is immediately leaked to the media.

Finally a word on what Steinitz refers to in just a few sentences: The submarine affair, in which “to my astonishment, I discovered that some of the dedicated people who had previously worked alongside me were being investigated” (p. 10). He is referring to Avriel Bar-Yosef, who Steinitz appointed as manager of the Foreign Affairs & Defense Committee, and David Sharan, who was head of his office, who were both indicted. Others who were investigated on this matter included Steinitz’s brother-in-law, his former adviser, head of his General Staff and his political adviser.

The Government Comedy is not a complete memoir and only purports to deal with selected episodes from Steinitz’s political biography. He himself was never questioned under caution on the submarine affair, but I think that someone who writes 300 pages and boasts of “historical achievements whose record will continue to accompany us in the future” (p. 9), and even takes the trouble to insert a rather irrelevant story about relations between Arnon Milchan and Yossi Cohen, could have covered such a critical matter slightly more extensively.