Publications

INSS Insight No. 2084, January 15, 2026

This article analyzes Islamic discourse among institutions and clerics associated with Syria’s new regime. The discourse reflects fundamentally hostile positions toward Israel and rejects peace with it; however, it is neither uniform nor static. Alongside rigid Islamist ideological expressions—most of which emerged in response to Israeli military activity in Syria—over the past year, there has also been a noticeable softening in tone and frequency. This trend does not indicate a deep ideological shift or the groundwork for full reconciliation, but it may allow for the legitimization of limited and bounded arrangements that can be justified as a hudna (temporary truce). Given these findings and the renewed diplomatic contacts between the two states, it is recommended that Israel not rely solely on a military arrangement but should aspire to a combined framework that also includes a declaratory political component—namely, a mutual commitment to resolve future disputes peacefully and to strive for permanent peace. Such a framework would create a horizon for a final political settlement further down the road and provide insight into the Syrian regime’s intentions—while formulating a proposal that both sides can adopt under the existing political circumstances.

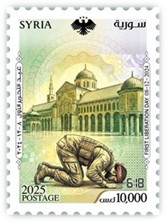

On December 8, 2025—the first anniversary of the Syrian revolution—the Syrian regime issued a series of stamps marking the historic event. One stamp depicts an elite fighter from Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a red headband on his forehead, praying in the courtyard of the famous Umayyad Mosque in Damascus at 6:18 a.m., the time when local media reported the city’s liberation. The ancient mosque—considered by some to be the fourth holiest site in Islam—became one of the symbols of the revolution. At the outset of the Arab Spring, it served as a focal point for protest demonstrations against President Bashar al-Assad, and it was there that the leader of the revolution and Syria’s current president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, chose to deliver his victory speech.

Religious symbols have helped the new regime shape the ethos of the “new Syria,” but they have not yet coalesced into a coherent policy clarifying the country’s direction. This is also true regarding the regime’s approach to Israel. Some believe that al-Sharaa was—and remains—a radical Islamist who views the capture of Damascus as “a station on the road to Jerusalem,” while others see him as a pragmatist seeking an arrangement with Israel as a guarantee for a future of peace, prosperity, and stability for his country.

Background: Islamism and Israel

The Islamist ideology—to which members of the current Syrian regime have adhered, at least in the past—has maintained a consistent and unequivocal position on the question of Palestine/Israel. From the founding of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt in 1928 to the present day, Islamists have opposed the establishment of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel, its recognition, and the conclusion of peace and normalization agreements with it.

Islamists present a structured set of arguments: Palestine is part of the Islamic umma; Palestine—and at its heart, Jerusalem—is land sacred to Muslims and belongs to them until Judgment Day, and therefore no part of it may be relinquished; violent and nonviolent jihad to liberate Palestine is an obligation incumbent upon every capable Muslim; Israel constitutes a Western outpost and embodies a military, cultural, and economic threat to its neighbors and to the Islamic nation as a whole; and Jews are viewed as the eternal enemies of Muslims from the time of Muhammad to the present, based on selectively chosen Quranic verses and traditions.

The conclusion drawn from this ideological doctrine—one that has enjoyed broad consensus among Islamist thinkers across generations and countries—is that Jews and Israel cannot serve as legitimate and desirable partners for permanent peace agreements with their Muslim neighbors.

At the same time, Islamist ideology does not reject hudna (temporary truce) as a pragmatic, time-bound solution appropriate to specific circumstances. The central Islamic precedent for a hudna is the Treaty of al-Hudaybiyya concluded in 628 between Muhammad and the Quraysh tribe. The agreement, set for ten years, lasted less than two; during that period, the Muslims grew stronger and ultimately conquered Mecca without a battle.

Over the years, Islamist movements—such as Hamas—have invoked the Treaty of al-Hudaybiyya to justify temporary ceasefires with Israel. In parallel, competing Islamic interpretations have relied on this precedent to justify permanent peace agreements with Israel. Thus, for example, the religious establishments in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates viewed it as evidence of Muhammad’s preference for the path of peace and argued that Jews—monotheistic “People of the Book”—were more worthy partners for an agreement than the pagan Meccans with whom the original treaty was concluded.

The Islamic Establishment in the “New Syria”

After al-Sharaa and his associates seized power, one of their first steps was reforming the state religious establishment in order to create a unified religious authority controlled by the new regime. The new religious establishment was integrated into al-Sharaa’s state-building efforts. Its role is not limited to issuing fatwas but also includes coordinating official religious discourse and legitimizing the emerging governing order.

In March 2025, the “Supreme Fatwa Council” was reestablished, comprising 15 members, with Sheikh Osama al-Rifa‘i (born 1944) appointed as its head. In the 1970s, he was involved in the Muslim Brotherhood, clashed with the regime of Hafez al-Assad, and was forced into exile in 1981. In the mid-2000s, he took advantage of a period of relative openness to return to Damascus and resume his religious activity. During the Arab Spring, he supported the uprising against Bashar al-Assad and was attacked by regime-aligned forces. In 2012, he again went into exile to Turkey, where he developed ties with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and in 2014 was appointed mufti on behalf of the Syrian opposition forces.

In April 2025, the council held its first meeting at the National Library in Damascus. Its members include clerics who have long accompanied al-Sharaa within HTS and held senior positions—foremost among them Mazhar al-Wais, who currently serves as the minister of justice in the Syrian government, and Abd al-Rahim Atoun, appointed in May 2025 as the president’s religious adviser. At the same time, the Syrian Islamic Council, which had operated on behalf of the exiled Syrian opposition until the revolution, was dissolved. Mohammad Khair Mousa, an expert on Islamic movements and schools of thought, explained that the new council brings together representatives from a range of currents: scientific, jihadi, and movement-based Salafism; scientific Sufism and Sufi orders; academic experts; and representatives of Damascene schools. According to him, the purpose of this diverse composition is to “bridge chasms, mend rifts, and unify visions.”

Muhammad Abu al-Kheir Shukri, a council member and figure in HTS, was appointed minister of religious endowments (awqaf). In an official directive circulated to preachers in May 2025, the Ministry of Awqaf defined the Friday sermon as a tool with a state-public function. The directive demanded adherence to the “harmonious middle path” (wasatiyya) and “moderate thought,” alongside the avoidance of vilifying institutions and individuals and an obligation to rigorously verify information and facts. Beyond limiting the sermon to 30 minutes, a more substantive change was the creation of a top-down guidance mechanism for the content of sermons, thereby narrowing the preacher’s independent discretion and prioritizing broader national, and potentially more pragmatic, considerations.

Islamist Discourse on Israel Before the Revolution

Before Syrian religious leaders assumed official roles in the new establishment, they were able to speak more freely, without the constraints imposed on an incumbent government. Although their activity focused on the struggle against the Assad regime, they frequently addressed Israel and consistently expressed Islamist-tinged positions rejecting peace agreements and supporting jihad.

Thus, on the eve of the signing of the Abraham Accords in September 2020, al-Rifa‘i joined other clerics in a fatwa issued by the International Union of Muslim Scholars, based in Qatar, which ruled that peace and normalization agreements with Israel are prohibited under Islam. About two years later, in July 2022, al-Rifa‘i met in Turkey with Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in an attempt to dissuade the movement from renewing ties with Damascus. In a statement following the meeting, al-Rifa‘i noted that Hamas constitutes “a source of inspiration for the umma” and that “the Palestinian problem is the problem of all Muslims.”

About two weeks after the October 7 attack, HTS held a solidarity conference with Hamas titled “From Idlib to Gaza—The Wound Is One.” Among the speakers was then-HTS senior jurist Mazhar al-Wais. He praised the actions of “our brothers, the jihad fighters in the Gaza Strip, on the beloved land of Palestine,” and referred to the “Zionist entity” as a “cancerous growth implanted in the heart of the Islamic world” by the West to fragment the Islamic umma and prevent its revival.

Al-Wais called on Arab and Islamic peoples not to be satisfied with solidarity but to stand with Hamas against Israel, “the enemy of the Islamic nation,” to spread jihad for the sake of God and strengthen the right of resistance. He clarified that jihad need not take the form of direct military action; it can also be carried out through money, speech, and mental effort. He concluded by praying that God grant victory to the people of Gaza and inflict defeat on their enemies.

Another speaker was Atoun, at the time the supreme legal authority in HTS. He declared that the holy land of Palestine is part of “Greater Syria” (al-Sham), an important component of the Islamic caliphate. According to him, there is no difference between Syrian and Palestinian—reflected in the participation of Syrian Muslim Brotherhood members in the 1948 war. Likewise, the current jihad in Palestine is an individual obligation (fard ‘ayn) incumbent upon all Muslims according to their abilities.

In subsequent months, Atoun added that the Zionist entity is a “bitter and persistent enemy of the Islamic umma,” not merely of Palestine or Gaza, and that Gaza’s civilians and jihad fighters are the “spearhead” of the campaign against it. On a Telegram channel bearing his name—apparently operated by him—there circulated prayers asking God to “repay the Jews for their plots by slitting their throats,” “curse them,” “destroy them,” and “deliver them as spoils to the jihad fighters.” Upon the death of Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, Atoun eulogized him on the channel, expressing hope that God would strengthen “our brothers in the Hamas movement” and subdue the Jews and their supporters.

Note. Al-Wais and Atoun at the solidarity conference “From Idlib to Gaza—One Wound,” October 2023, YouTube.

Change and Continuity in Religious Discourse on Israel After the Revolution

Since the revolution, HTS’s combative tone has been moderated in favor of messages emphasizing stability, governance, and internal reconstruction—raising the question of whether this reflects genuine ideological shift or tactical pragmatism aimed at ensuring the consolidation and survival of the Syrian Islamist project.

For example, since his appointment as minister of justice, al-Wais has emphasized the distinction between “ideology” and “state management” and has provided Islamic legal justifications for cooperation with the international coalition against ISIS, on the grounds of maslaha (action that safeguards the principal objectives of Islamic law—literally, “interest”), preservation of state sovereignty, and the obligation to fight the khawarij (religious rebels).

Regarding Israel, however, the situation is more complex. While political figures associated with the new regime have voiced conciliatory messages in favor of dialogue and arrangements, the religious establishment has not aligned itself with the political echelon and has, at most, reduced the intensity and frequency of hostile rhetoric toward Israel. Moreover, over the past year, there have been statements echoing Islamist conceptions.

Escalations in religious rhetoric have generally followed Israeli military actions in Syria. Thus, in April 2025, in one of his first declarations as grand mufti, al-Rifa‘i referred to an IDF strike carried out in late March in Daraa province in southern Syria, which killed six people and wounded others. During a condolence visit to the victims’ families, he declared that “these martyrs were killed by the worst of God’s enemies—the most hostile and despicable.”

About three months later, in July 2025, the Supreme Fatwa Council under his leadership issued an official fatwa in response to Israel’s involvement in the bloody clashes that erupted in Suwayda between local Druze militias and Bedouin tribes with the involvement of al-Sharaa’s forces. The fatwa condemned Druze forces that sought Israel’s assistance, stating that “it is agreed and self-evident that it is forbidden to betray and turn to the occupying and deceitful Zionist enemy for help against your own state. This enemy proves time and again that it deserves only enmity, not agreements and contracts.”

Throughout 2025, the Telegram channel associated with Atoun published posts expressing solidarity with the Palestinians’ struggle in Gaza and longing for God to grant them victory over their enemies. On the second anniversary of October 7, Atoun wished for God to enact justice, take revenge on the Zionists, punish them for the wrongs committed against the oppressed in Palestine, and show mercy to the “people of Islam in Gaza” who made great sacrifices.

Moreover, Syrian preachers supportive of the regime but who do not hold official positions have been documented delivering anti-Israel and anti-Jewish sermons in mosques despite tightening state supervision. For example, a preacher in Aleppo advocated preparation for jihad against Israel, called Jews “enemies of God,” and referred to them as “murderers, sinners, and infidels.”

Current Syrian religious discourse does not lay the groundwork for full peace, but neither does it necessarily reject more limited arrangements, such as a return to the 1974 Disengagement Agreement between Israel and Syria. This format is closer to a hudna, which, from an Islamist perspective, may be considered a legitimate choice reflecting the regime’s awareness of the existing balance of power and enabling it to focus on Syria’s reconstruction and consolidation of its rule—without recognizing Israel as a permanent reality or retreating from its principles.

Indeed, over the past year, several clerics and activists supportive of the new Syrian regime—though not holding official positions—have cited the Treaty of al-Hudaybiyya as a precedent for an agreement with Israel, sparking heated debate on social media. It is difficult, however, to assess whether they meant a temporary truce or permanent peace; the ambiguity may well have been deliberate, avoiding firm commitment and allowing different audiences to interpret the message as they see fit.

For example, Ma’moun Hamah (Abu Wael), a Syrian activist in exile and a supporter of al-Sharaa who runs a Facebook page with over 200,000 followers, circulated several viral videos in 2025—garnering millions of views—in which he mentioned al-Hudaybiyya as a precedent for peace with Israel and the Jews. In a video published in early 2025, he explained that Israel is not the Syrian people’s primary enemy; rather, it is the Assad regime, Iran, and their proxies. According to him, God commanded Muslims to fight those who fight them, while Israel remained neutral throughout the Syrian civil war.

His conclusion was that Syrians must not act emotionally toward Israel, as Hamas did on October 7, but rather rely on reason and wisdom. In this context, Abu-Wael recalled that the Prophet Muhammad preferred the Treaty of al-Hudaybiyya because it enabled people to convert to Islam without war. As he put it: “We will sign [with Israel] a Treaty of al-Hudaybiyya . . .We are now in peace until God, the Exalted and Sublime, grants us a way out or bestows upon us victory without battle.”

Conclusions and Recommendations

An analysis of Islamic discourse in the new Syria indicates that the religious establishment is not, at this stage, preparing the ground for a permanent peace agreement with Israel and may even oppose a political echelon that chooses this path. At the same time, there is greater political and religious openness to limited security arrangements, such as a disengagement agreement that could be interpreted as a form of hudna, a temporary truce. This raises a fundamental question: should Israel promote such an arrangement with a regime that has Islamist ideological roots? The answer is complex.

On the one hand, returning to a framework akin to the 1974 Disengagement Agreement offers significant advantages: It would improve and stabilize the security situation along the Israel–Syria border; protect the Druze on the Syrian side of the border; not require painful territorial concessions on the Golan Heights; be easier for both states to legitimize domestically; and, hopefully, help build trust toward a broader agreement in the future, if and when conditions ripen. Such an agreement could also encourage the regime to adopt a more moderate line, restrain hostility toward Israel, and provide Israel with leverage to influence a regime in formation toward desirable and positive directions.

On the other hand, such an agreement also has drawbacks: It could allow a hostile Islamist regime to consolidate power in Syria and endanger Israel and its regional partners in the medium to long term; it would create a precedent whereby states in the region could still settle for agreements that do not include permanent mutual recognition and broad normalization with Israel; and finally, it may squander an opportunity to reach a more meaningful agreement with a fragile regime desperate for political and economic gains and potentially willing to consider far-reaching compromises to reach an arrangement with Israel—such as long-term leasing of the Golan Heights.

A possible way out of the dilemma lies in creating a third, non-binary option between “peace” and “hudna.” One possible formula would be a security arrangement that includes a declaratory political horizon, such as a mutual commitment by both states to resolve future disputes peacefully, refrain from the use of force, and strive for a permanent peace agreement. This approach—similar to that implemented in the Israeli–Egyptian interim agreement of 1975 brokered by the United States—addresses the need to improve the security situation in the short term while creating a horizon for a final political settlement in the medium or long term.

Such a bridging formula could allow for testing al-Sharaa’s long-term strategic intentions toward Israel. A regime willing to declare its readiness for a permanent peace agreement—not merely a temporary hudna—could more credibly claim to have abandoned radical Islamist ideologies. More friendly, less confrontational Israeli conduct would likely make it easier for Syria’s president to go the extra mile.