Publications

INSS Insight No. 1701, March 27, 2023

Iran-China relations have seen several twists and turns over the past few months, from unusual Chinese statements against Iran during President Xi’s visit to Saudi Arabia and diplomatic tension between the countries, followed by a precedent-setting visit by Iranian President Raisi to China and the signing of continuing economic agreements, to Chinese mediation in formulating the agreement to renew Iranian-Saudi relations. China-Iran relations are stable and based on strong foundations of common opposition to US hegemony in general and in the Middle East in particular, significant mutual economic interests (notwithstanding greater Iranian dependence on China than Chinese dependence on Iran), and security cooperation. Yet despite declared progress in their relations through the recent series of agreements, sanctions against Iran harm their economic relations and make it difficult to realize these agreements. However, China may still leverage its relations with Iran as a bargaining chip vis-à-vis the US.

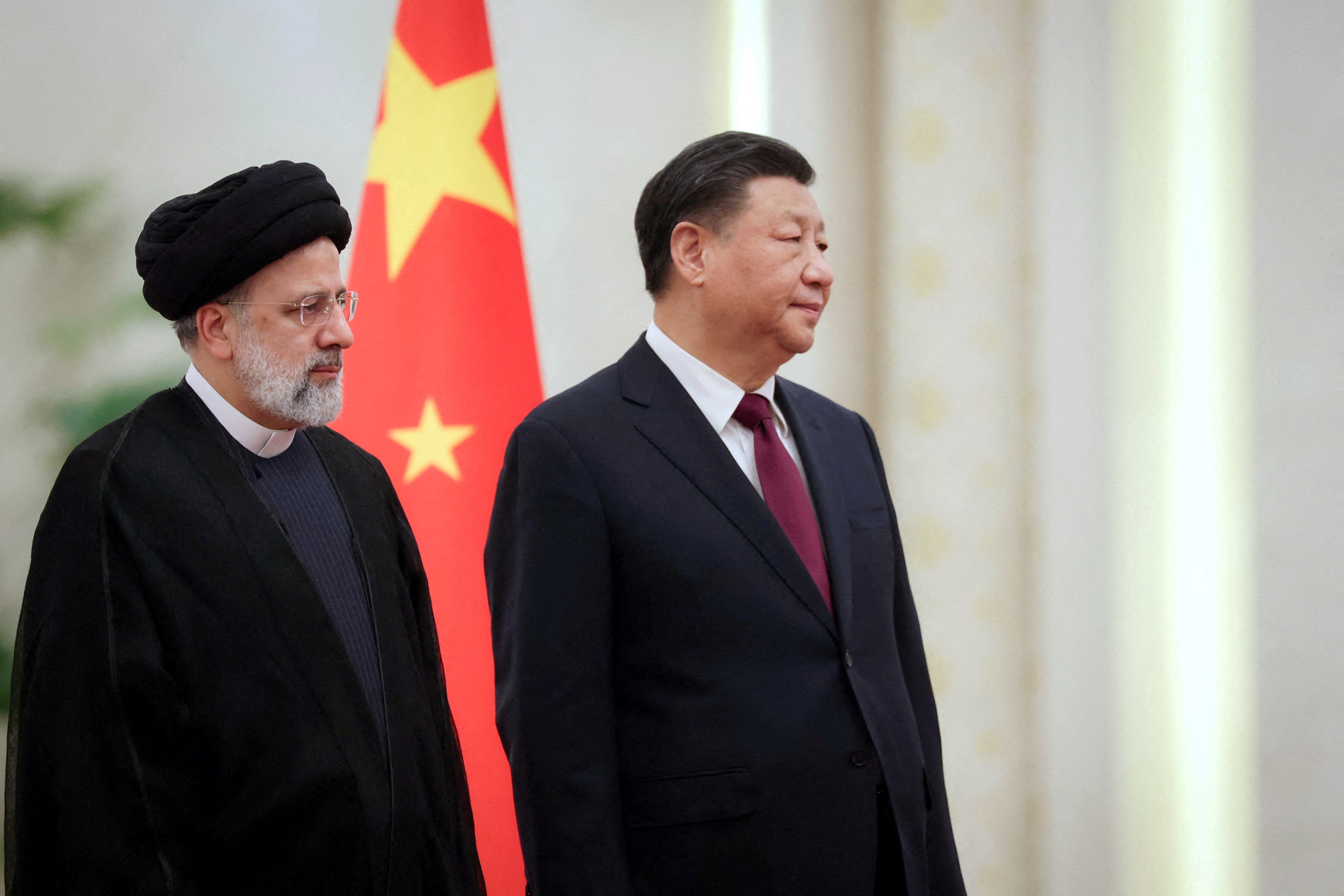

In mid-February 2023 Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi visited China at the invitation of President Xi Jinping. The visit aimed first and foremost to balance the visit by China’s President to Saudi Arabia and the summit meeting there with the Gulf Cooperation Council states. A large delegation of ministers accompanied Raisi, and during the visit short and long-term agreements were signed in the fields of commerce, agriculture, industry, and infrastructure. Likewise, the two sides continued to advance the implementation of the long-term 25-year agreement that they signed in March 2021, and almost twenty memoranda of understanding valued at some $10 billion were signed. During the visit, President Xi declared that Beijing resists the meddling of external powers in Iran’s internal issues and issues that harm security and stability, and promised to cooperate with Iran on subjects that involve the two countries’ vital interests. On the nuclear issue, he expressed willingness to take part in talks to renew the agreement, criticized the US for withdrawing from the agreement, and called for its implementation.

China-Iran relations are based on ideological, economic, and security mutual interests. Ideologically, the states both oppose the US and the unipolar American order. Inter alia, China sees Iran as a party occupying US attention in the Middle East, at the expense of refocusing its attention on Asia, which would directly harm China. Chinese and Persian civilizations also have historic links going back “some 2000 years.”

Economically, Iran is highly dependent on exports to China, which receives the highest share of its exports (some 21 percent of all Iranian exports, according to official statistics, and nearly 30 percent according to estimates that include sanctions-evading energy exports). It is highly interested in drawing Chinese investments in its economy. China sees Iran as a source of cheap energy and as its only supplier in the Persian Gulf (a critical energy region) that can be relied upon not to submit easily to US pressure in the event of China-US tension; as a large consumer market for the export of Chinese goods; and as a country that controls important trade routes for the Road and Belt Initiative. Moreover, China also believes that Iran has unfulfilled economic potential due to its prolonged disconnect from the global economy, and in light of its large, young, and relatively well-educated populace.

In security terms, Iran is interested in Chinese military assistance (and even conducted several joint exercises with China and Russia in the past few years) and in diplomatic support for its nuclear program, while for its part China does not feel threatened by Iranian nuclear threshold capabilities – although it does not have an interest in Iran violating the NPT and breaking out to a nuclear weapon.

In recent years, bilateral diplomatic relations were enhanced through a series of announcements and events, including a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement (2016), a 25-year cooperation agreement (2021), and an agreement formulated this past September regarding Iran joining the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), led by China and Russia. This agreement was reached after many years of Iranian diplomatic efforts, and is supposed to be implemented soon. In practice, however, the bilateral relations did not reach the expected heights, particularly due to the economic barrier created by US sanctions on free Chinese trade and investments in Iran, and while trade between China and Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and oil imports from the latter two exceed those from Iran and are more important to China. For example, the reported trade volume in 2022 between Iran and China (aside from unreported energy trade) was some $15.7 billion, and in 2021, $14.7 billion – much less than the reported trade volume before the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement in 2018, when it was two to three times higher.

Over the past few months, a number of negative developments marked China-Iran relations. First, the impasse in talks on renewing the nuclear agreement made it clear to China that it was unlikely that sanctions on Iran would be withdrawn any time soon, in a manner that would allow it to fulfill its economic potential. For now, though, China can exploit increasing Iranian dependence on it without fear of Western competitors. Second, the tension between Riyadh and Washington created an opportunity for China to try to increase its influence in Saudi Arabia and to exploit declining Saudi loyalty to the US, which until now was a disadvantage vis-à-vis Riyadh compared to Iran, which was considered a more reliable energy source that is better able to withstand US pressure.

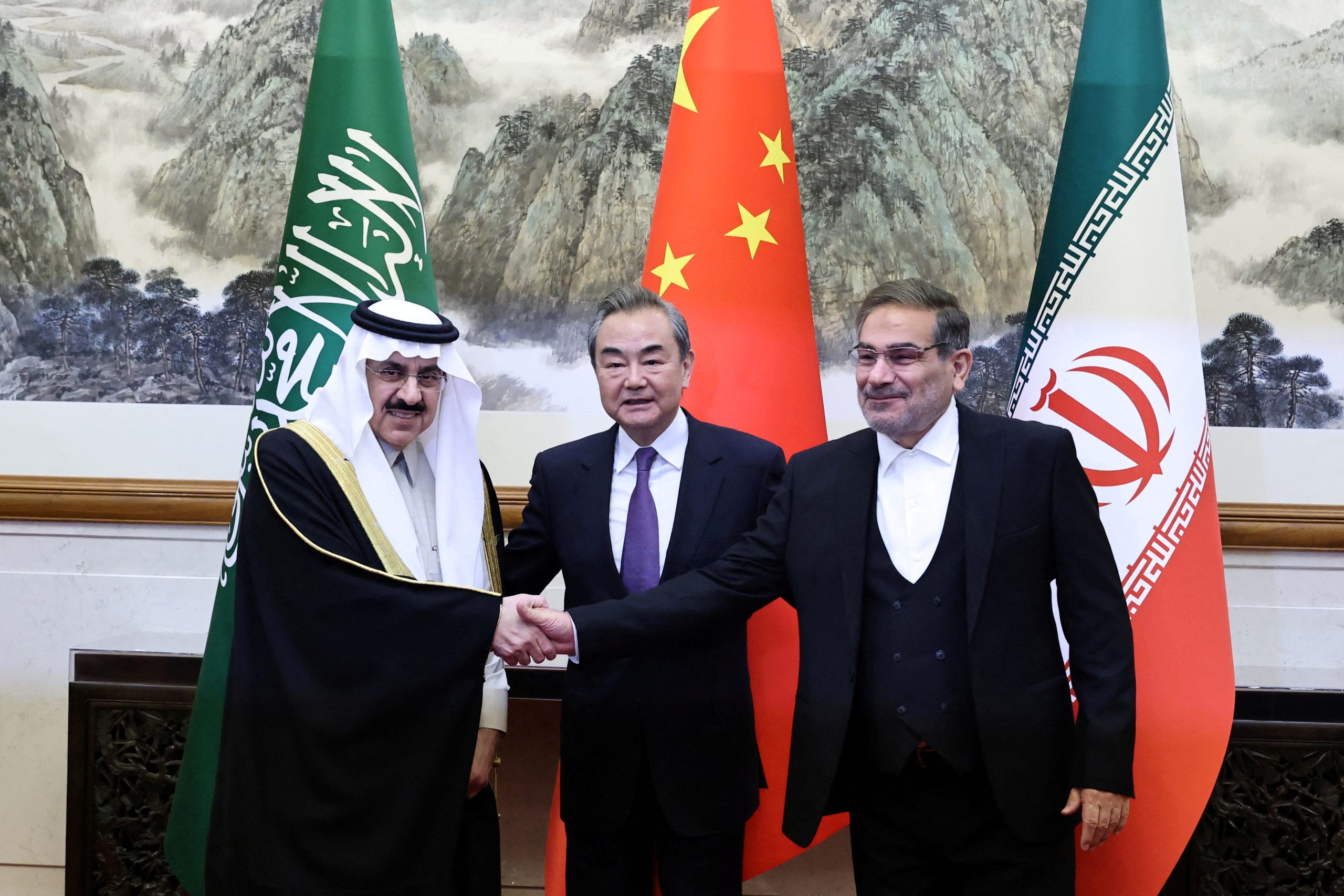

Last December, for the first time since 2018, the Chinese President visited the Middle East and held three summit meetings in Riyadh with Saudi Arabia, the GCC states, and 21 members of the Arab League (Syria was absent). The visits were held against the backdrop of increasing tension between the US and Saudi Arabia (and Biden’s visit to Riyadh, which was chillier than Xi’s); the global energy crisis caused by the war in Ukraine; and Iranian assistance in supplying UAVs to Russia for its war in Ukraine. Alongside a series of memoranda of understandings and signed agreements worth tens of billions of dollars, a joint statement was issued with the GCC states, portions of which were understood as direct criticism of Iran. Tehran was angriest about the call for negotiations between Iran and the UAE over three disputed islands in the Straits of Hormuz: Greater Tunb, Lesser Tunb, and Abu Musa. Iran conquered these islands in 1971, has viewed them ever since as an integral part of its territory, and does not recognize Emirati claims to sovereignty there.

The harsh Iranian response to the statements was sounded through criticism in newspapers, statements by senior regime officials, and a summoning of the Chinese ambassador for clarifications. In response, then-Vice Premier Hu Chunhua declared that China supported Iranian sovereignty and territorial wholeness, and was still interested in developing comprehensive strategic relations. Likewise, China voted against expelling Iran from the UN Commission on the Status of Women, praised Iranian efforts in nuclear talks, and blamed the US for their failure. At the same time, China inaugurated its first consulate (whose opening had been authorized the previous year) in the Iranian Bandar Abbas port, which is considered the country’s most significant, both commercially and militarily (and is home to the Revolutionary Guards’ central naval base).

The bottom line is that Raisi’s visit to China, in the wake of the statements that emerged from Xi’s visit to Saudi Arabia, aimed to ensure that bilateral relations between Iran and China were not weakening. After the visit, China surprised the world by mediating in Beijing between Iran and Saudi Arabia, which announced on March 10 that they are renewing diplomatic relations (which were severed in 2016) and exchanging ambassadors. The Chinese move reflected increased Chinese involvement in the Gulf, and an interest in maintaining regional stability while strengthening China’s status vis-à-vis the US. Raisi’s unprecedented visit to China also allowed Iran to present a political achievement with potential to ease the economic challenges it faces, in light of increasing international political pressure and the temporary tension between Tehran and Beijing after the Chinese President visited the Gulf. Externally, this is a message that shows Iran’s ability to rely on China to cope with Western sanctions, especially as protests against the regime die out and advancement in the nuclear program continues and reached the peak of 84 percent uranium enrichment – as reported by the IAEA.

Raisi’s visit to Tehran, the first official visit by an Iranian president in China in two decades, ostensibly represents additional progress in China-Iran relations. However, it is still too early to determine whether China will fulfill its commitments and the additional agreements signed during the visit, and enhance its relations with Iran in a substantial way via military and economic cooperation beyond the declarative level. First, other than the desire to dispel tension between the states, China sees its relations with Iran as a bargaining chip vis-à-vis the US, as part of the global competition between the two. While the US speaks about China in a harsher tone and increases the pace and scope of limitations on trade, China can threaten to strengthen Iran economically and militarily if the US takes its severe line too far. China-US relations are more important for China than relations with Iran, and in the past, it was willing to harm Iranian interests when it needed to do so for the good of relations with the US. In the past, the Chinese linked cooperation with the US on Iran to easing of US policy toward China in Taiwan.

Second, it is still not clear to what extent Iran has managed to turn the strategic 25-year agreement with China, which functioned as a roadmap, into concrete practical commitments. Either way, China still has space to maneuver and in the past withdrew from certain deals (such as the CNPC state-owned gas corporation withdrawing from the development of an Iranian gas field worth $4.8 billion dollars after Trump withdrew from the nuclear agreement and reimposed sanctions on Iran). In the background are additional obstacles independent of sanctions that influence relations between the two states and bilateral trade, such as mutual distrust, formidable Chinese bureaucracy, and Iranian terrorism, which undermines stability in the Middle East.