Publications

Strategic Survey for Israel 2019-2020, The Institute for National Security Studies, January 2020

The most significant conventional military threat to Israel is posed by the northern arena, specifically, from Iran and those under its patronage: first and foremost, Hezbollah in Lebanon, followed by the Assad regime and militias active in Syria and Iraq under Iranian guidance, and Iranian (and Hezbollah) forces active in the Syrian arena. In addition, Israel must consider how the targeted killing of Soleimani might impact on the northern arena. In recent years, Israel has adopted a “campaign between wars” strategy in order to reduce the threat in the northern arena and to obstruct enemy measures that seek to entrench Iranian and pro-Iranian military capabilities and militias along Israel’s borders, while strengthening deterrence and staving off war. So far, Israel has succeeded in disrupting Iranian progress, but in the past year the risk of escalation has increased, with Israeli activity focused against two principal efforts: Hezbollah’s precision missile project in Lebanon and that of Iran in Syria; and Iranian moves to establish a land bridge from Iran through Iraq and Syria. During 2019 it became clear that Iraqi territory is also used by Iran as a possible platform to attack Israel with missiles.

Principal Trends and Expectations for 2020

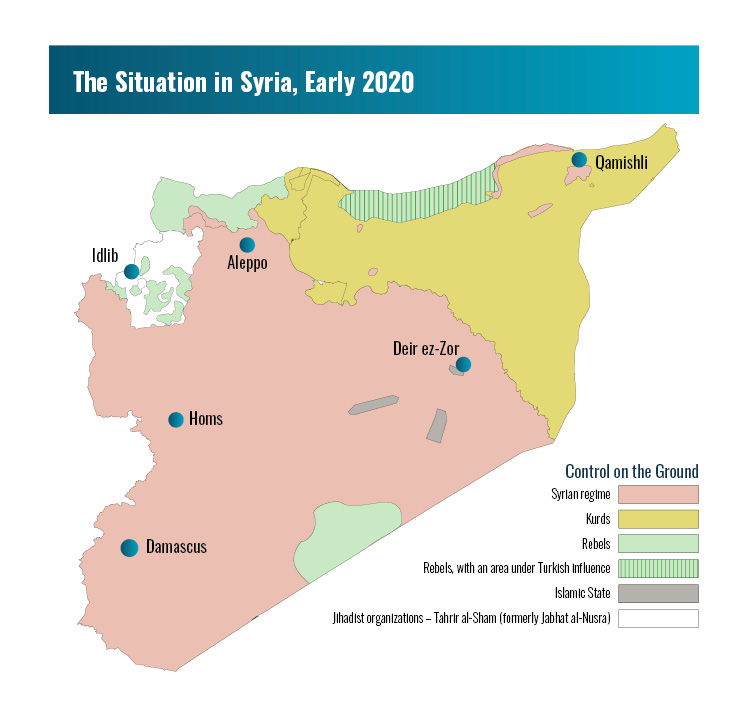

Syria is still far from functioning as a unified state. President Bashar al-Assad remains in power, but he is entirely dependent on Iran, Russia, internal security apparatuses, the army, militias, and criminal elements. In his eyes, the survival of his regime is paramount: he strives to establish a political and military order that is similar to what existed before the civil war; prefers to invest in rebuilding the army rather than rebuilding the state’s infrastructures; will continue to engage in demographic “cleansing” by removing or weakening unwanted (especially disloyal) populations and preventing the return of refugees; and will maintain his chemical warfare capabilities. The Syrian army is being rebuilt under Russian influence with Iranian involvement, with an emphasis on air defense, high trajectory fire including precision missiles, high mobility, and special forces.

It is too early to assess how the killing of Soleimani will impact on Iran’s regional activity. Iran is expected to continue to exploit Assad’s weakness in order to consolidate its multidimensional influence in Syria: build the war machine in the theater and strengthen the Shiite supply axis from Iran via Iraq to Syria and Lebanon. Iran will continue to transfer advanced missile capabilities to Syria and strengthen the readiness of the militias that are under its authority, which include tens of thousands of operatives located within the Syrian arena. Some are intended for fighting against Israel, others for ongoing missions to retain territory in the area, along with upgrading and reinforcing Hezbollah outposts on the Golan Heights.

Russia is unlikely to push Iran out of Syria in 2020. Its network of interests vis-à-vis Iran is broader, and from its perspective, Iran has a role to play in stabilizing Assad’s regime. However, it is likely that Moscow will not let Iran establish itself in Syria in a way that threatens Russian interests – both economic interests and those connected to the stability of the Assad regime.

In northern and northeastern Syria, it seems it will be difficult to stop Turkey from reinforcing its influence, all the more so in light of the reduction of the American presence there in late 2019. Turkey conducted a military operation to construct a 32-kilometer wide safe zone on the Syrian side of the border, in order to create a barrier between the Kurds and Syria and the Kurds in Turkey. In Ankara’s view, an effective means of creating the barrier is to exploit the territory to settle Syrian refugees, mainly Sunnis, who fled to its territory, and deploy rebel forces subject to its authority. As such, it seeks to achieve two goals: reduce the heavy burden of the refugees, and reduce Kurdish dominance in the area. The immediate response of the Kurds was a willingness to reach an agreement with the Assad regime with Russian mediation, in return for a guarantee from Russia and the regime of the right to autonomy in northeastern Syria. In addition, a Russian-Turkish agreement led to a ceasefire and the agreement of Kurdish forces to withdraw from the border, such that Russian and Turkish forces conduct joint patrols of the territory.

There is only a slim chance in 2020 of seeing governmental reforms in Syria or a viable agreement between the opposition and the Assad regime sponsored by the countries involved – Russia, Iran, and Turkey – and the greater international community. Furthermore, it does not appear that there will be budgets or motivation for civilian reconstruction of Syria. The issue is not a top priority for China, Europe, the United States, or the Sunni states.

In Lebanon, after an extended political deadlock, a new government was formed in early 2019, but it has had difficulty taking decisions and spearheading improvement in the severe internal situation (deep economic crisis; lack of infrastructure; unemployment; corruption; and the burdensome presence of Syrian refugees). The increasing distress of the population, along with the paralysis of the political system, led to the spontaneous outbreak (October 17) of large-scale popular protests, singular in nature insofar as they did not differentiate between communities and targeted all of the elements comprising the government (both the Sunni camp led by Prime Minister Hariri, who resigned, and the Christian-Shiite camp, which includes President Aoun and Hezbollah as a political movement). The demonstrators demand substantive change in the political system and the leadership and elimination of government corruption. Hezbollah is not interested in change because the current system serves its interests; in any case, in different scenarios Hezbollah would likely retain its independence and its increasing influence on decision making processes in Lebanon. It thus remains possible that the Lebanese system could collapse and even deteriorate into another civil war.

Significance and Recommendations for Israel

Israel can point to many operational achievements in recent years in the northern arena, due to intensive offensive activity with an impressive level of operational efficiency in the campaign between wars, which has allowed Israel to avoid war. However, on the strategic level, Israel has not prevented Iran’s ongoing consolidation in the northern arena and construction of its war machine in Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq.

Israel’s Campaign between Wars

In 2020, Iran is expected to further its entrenchment in Syria on social, cultural, economic, and infrastructure levels. Iran is also developing offensive capabilities for attacking deep into Israel from Syrian territory and possibly also from Iraqi territory, while adopting rules of the game that are similar to the Israeli campaign between wars. In this context, Iran’s activity and its high level operational capabilities were evident in the attack on the oil facilities in Saudi Arabia, and in the attempts to launch rockets and drones toward Israel from Syria. Overall, there is increased potential for escalation between Israel and Iran and its proxies from the Syrian and Iraqi spheres, particularly following the killing of Soleimani.

This dynamic highlights the Israeli challenge of waging the “ongoing campaign below the threshold of war” against Iranian buildup in the northern arena, and the need for coordination with the United States. In 2020, it seems that Israel will have difficulty controlling the levels of escalation, because the enemy is now familiar with the IDF’s capabilities and has improved its defense, while developing offensive response capabilities. In addition, to the extent that stability in Syria is further undermined, Russia could impose limitations on Israel’s freedom of operation in Syrian airspace. Israel would do well to return to the policy of deliberate ambiguity, employ more covert capabilities, and refrain from public arrogance regarding its operations in the northern arena.

Israel should reassess its policy of non-intervention in the civil war in Syria. Israel’s ability to damage the Assad regime served as a means of leverage, especially toward Russia, which enabled it to operate in the Syrian arena against Iran and its proxies. But this policy also led to informal recognition of the Assad regime as the victor in the civil war. The ongoing campaign and Israel’s damage capability can lay the groundwork for a complementary political process that could remove Iranian capabilities that threaten Israel from Syria, whether via Russian pressure on Iran or via President Assad’s understanding that the Iranian activity in Syria exacts too great a toll.

The killing of Soleimani sparked a reinforcement of US forces in the region. However, this might be a prelude to an accelerated withdrawal of US forces from Iraq and eastern Syria. A development of this sort will grant a victory to US adversaries in the competition over shaping the Syrian sphere: Russia, Iran, and the Assad regime, which together will receive a strong grip on northeastern Syria. In addition, it is possible that the Islamic State will reappear, despite the US operational and moral achievement of assassinating its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Improved Preparedness for War in the Northern Arena is Imperative

The loss of control over the levels of escalation, the increasing confidence of Iran and Hezbollah, and above all, their increasing number of precision missiles raise the likelihood of a war between Israel and Hezbollah and the Shiite axis in the northern arena. Israel must decide if a particular number of precision missiles in Hezbollah’s possession demands a preventive attack to remove or significantly reduce the threat. A successful Israeli attack to prevent the construction of an arsenal of precision missiles in Lebanon would increase the risk of war.

As part of his risk management, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah estimates that the organization’s actions in Lebanon enjoy “immunity,” based on the mutual deterrence with Israel since 2006. According to the equation that has developed, if Hezbollah does not attack Israel from Lebanon, then Israel will not attack in Lebanon. Based on this working assumption, Hezbollah advanced the missile conversion project together with Iranian Revolutionary Guards Quds Force commander Soleimani, and over the course of a decade dug attack tunnels (exposed and neutralized by Israel in Operation Northern Shield). Nasrallah is wary of war, given his familiarity with Israel’s capabilities, as well as due to the organization’s internal and economic difficulties and Lebanon’s unstable situation. The organization is torn between its increasing responsibility for the Lebanese state and its commitment to its patron (Iran) and its commitment to respond to Israeli attacks in Lebanon and perhaps even to serious attacks on Iranian forces in Syria.

It will be difficult to limit the next war to the Lebanese front, and it is likely that it will unfold on several fronts at once: Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and possibly Iran itself. Israel’s security cabinet decided this year to strengthen Israel’s defense capabilities, especially against missile and unmanned aerial vehicle attacks. In practice, Israel must also strengthen the preparedness of the home front, improve its defense ability and the means of protection, and reinforce the pillars of civilian resilience in communities in the north. In tandem, the political-economic-cognitive effort to weaken Hezbollah (which bore fruit over the past year with the sanctions on Iran, the recognition of Hezbollah as a terrorist organization by a greater number of states, and the civil unrest in Lebanon) must be maintained, even though it may undermine the performance of the Lebanese state.

Coordination with the World Powers

Israel should continue its close relations and coordination with both world powers relevant to the Syrian context – Russia and the United States. Russia has an interest in reducing long term Iranian influence in Syria, but it does not want and cannot remove it from Syria due to the complexity of the strategic relations between the countries on other levels. However, given its increasing influence on the reconstruction of the Syrian army, Moscow has the ability to at least slow the construction of the Iranian war machine in Syria, which depends on Syrian national and military systems and infrastructure. Coordination with Russia is also essential for maintaining Israel’s freedom of operation, preventing military friction, and formulating a shared picture of the challenges before them. Israel must continue to place political pressure on Russian President Putin in order to prevent the supply of advanced air defense systems to the Assad regime, especially as long as he enables Iran’s buildup in his territory.

The likelihood of a scenario in which Russia distances Iran from Syria in 2020 is low. Pavel Golovkin / Pool via REUTERS

Despite the US desire to withdraw its forces from northeastern Syria, Israel must continue its attempts to include the United States in the process of crafting an arrangement in Syria, and to cultivate an American commitment to block the Shiite supply axis between Iraq and Syria (and Lebanon). The United States is expected to continue to provide political backing to Israel (on the condition that Israel not entangle it in conflicts in Iraq and in eastern Syria) but will refrain from getting drawn into another war in the Middle East. Consequently, Israel and the United States would do well to consider a Russian offer of removing Iranian capabilities that threaten Israel from Syria, in return for the easing of American sanctions on Russia and on Iran. Such an arrangement could be feasible if a formula is created for returning Iran to negotiations on an updated nuclear deal (JCPOA), which includes a reduction of its intervention in the region.

The Israeli interest is to strive to develop a broad group of partners for preventing the consolidation of the Shiite- Iranian axis from Tehran to the Mediterranean Sea. Aside from the United States, potential partners are the Sunni Arab states and European states. Part of the process should also include strengthening control of the border crossings between Syria and Lebanon – which would restrict the Iranians and Hezbollah, and at the same time (at least ostensibly) strengthen Lebanese sovereignty. An alternative plan for Syria’s reconstruction led by the West and the Sunni Arab states should be prepared, rather than leaving the reconstruction to Iran by default. Israel can also take part in such an effort and, via a third party, direct investments toward southern Syria, especially the Quneitra and Daraa governorates on the Syrian side of the Golan Heights.

Conclusion

It has become clear that the assessments that Assad defeated his opponents were premature, and the civil war in Syria is expected to continue at a low intensity. Iran will use the struggles among the internal and external actors to continue its buildup in Syria, and Salafi-jihadist elements may likewise exploit the situation for their own revitalization. The economic and humanitarian crisis will continue for the lack of a Western element that is willing to invest in Syria while Iran is involved and Assad remains in power. All of the relevant actors will have difficulty formulating a political settlement and implementing governmental reform in Syria, certainly one that would end Assad’s rule.

The winds of war in the northern arena are blowing stronger than in previous years. Israel could lose two of its prominent advantages: first, its ability to operate freely against the construction of the Iranian war machine in Syria, without risk of escalation; and second, the knowledge that the United States would stand with Israel and block the Shiite supply axis from Iran via Iraq to Syria and Lebanon. Consequently, Israel must formulate an updated plan for the ongoing campaign against Iranian consolidation in the northern arena, and at the same time, prepare for a multi-theater military challenge that it might face alone.

The next Israeli government faces four serious strategic decisions:

* The first involves the set of responses to an Iranian attack on military and national infrastructure deep within Israel using cruise missiles, high trajectory weapons, and unmanned aerial vehicles.

* The second considers whether to change the policy toward the Assad regime and see it as responsible for developments in Syria, including the Iranian involvement.

* The third debates whether there is a red line regarding Hezbollah’s precision missile stockpile that would demand an Israeli preemptive strike to remove the threat to the home front under conditions that are more favorable to Israel than postponement of the war to an unknown time in the future.

* The fourth examines how to intensify the campaign against Iran’s influence in Iraq while leveraging the effect of Soleimani’s killing and the close coordination with the United States.