Strategic Assessment

Israel possesses a vast, environmentally-friendly, cutting edge and effectively inexhaustible potential fuel resource: the large-scale production of green and blue hydrogen in the Negev. The country’s energy resilience depends to a considerable extent on harnessing this resource and fully realizing its latent potential. Following the weakening of the Iranian axis, the threats facing the State of Israel may have changed but have not disappeared. Threats to the energy sector occupy a distinct and critical position, given its essential role in both the economy and defense.

This article examines the nature of future geopolitical threats to Israel’s energy supply chains and infrastructure, with particular emphasis on the unique characteristics of oil and the dependence of the transportation and industrial sectors on it. The point of departure is the assumption that Israel must prepare for the emergence of a “cold conflict” with Turkey; under such circumstances, Turkey’s extensive leverage over Israel’s oil supply routes constitutes a clear threat to the country’s energy resilience.

Identifying these threats points to the required systemic response: the decentralization and diversification of production and transmission sources. In this context, the article argues that one of the most important systemic responses lies in the production of green and blue hydrogen within an advanced infrastructure network to be established in the Negev.

Keywords: hydrogen; Negev; Turkey; energy storage; energy resilience; cold conflict

Introduction

National energy resilience constitutes a foundational pillar of security, as well as economic, environmental, and geopolitical resilience. This article examines the issue from two perspectives. The first is an assessment of the developing threat posed by the emerging “cold war” between Israel and Turkey, with particular attention to vulnerabilities within the energy sector under such conditions. The second is the global trend in hydrogen fuel, which offers a significant response to the need to strengthen energy resilience in the face of this threat.

Following the definition of the challenge and the required systemic response, this article proposes a strategy for the development of a hydrogen-based infrastructure and technological ecosystem, the core of which would be established in the Negev.

The deterioration of Israel–Turkey relations has already been characterized as an emerging “cold war” (Cohen Yanarocak, 2025b) between two of the most powerful regional actors in the Middle East. This development has become particularly pronounced following the relative weakening of the Iranian axis, which had posed a threat to both states, following the series of wars that followed October 7, 2023. The process began with escalating rhetoric and continued with the imposition of an economic embargo, initially identified as a move that was more likely to harm Turkey itself and isolate it from the United States (Lindenstrauss & Daniel, 2024; Cevic, 2025).

Recent developments, however, have reshaped this assessment. Turkey has gained a prominent position at the negotiating table, received a renewed and warm embrace from the United States—including arms deals—and secured a potential foothold in post-war arrangements for Gaza (Lazimi, 2025). This trend is further reinforced by Turkey’s neo-Ottoman imperial narrative, its sphere of influence in Syria under the al-Jolani leadership, and its growing entrenchment through alliances and military bases across the Mediterranean and the Red Sea (Dekel, 2024b; Spanier and Horev, 2019). Taken together, these developments indicate that Turkey is striving for regional hegemony, expressing hostility toward Israel while supporting its adversaries, and extending its strategic reach to encircle Israel in both its immediate and wider regional environment (Cohen Yanarocak, 2025a).

There is no consensus among scholars that an escalation is inevitable, and it is possible that the two states will continue to balance their interests “through clenched teeth” without coming into direct confrontation (Epstein, 2025). Nevertheless, the trend is deeply troubling and necessitates a level of readiness that is not grounded in excessive optimism. Although, unlike Iran, Turkey’s dependence on the West constrains its ability to escalate tensions (and Israel is likewise constrained from acting against Turkey, also due to Turkey’s military power, which is not comparable to that of Israel’s other adversaries), in the medium and long term Israel must prepare for a confrontation that may assume various, as yet unknown, forms—for example, a “cold conflict,” proxy confrontations, or attacks conducted through means that cannot be directly attributed to Turkey.

At the same time, Israel has yet to formulate a coherent policy in response to the emerging threat, and the scholarly and strategic discourse on this new trend remains in its infancy. In this context, the article focuses on the dangerous lever Turkey holds over Israel in the energy domain: Turkey serves as the transit state for most of the oil imported by Israel, exercises control in various ways over all maritime routes leading to Israel, and possesses the offensive capabilities required to strike components of the energy system’s infrastructure. Only a level of resilience based on reducing dependence on oil will enable a long-term response to these risks, as well as to more familiar threats, such as the Iranian axis.

Threats to Israel’s Energy Resilience

Concerns regarding national energy resilience have preoccupied policymakers, researchers, and strategists for many years (see, for example, Becher, 2024; Grossman & Efron, 2016; Weinstock & Elran, 2016; State Comptroller, 2020; Madar, 2023; Cohen, 2025). Even if the threat of international isolation does not materialize (“Super-Sparta,” in Netanyahu’s words) and that Israel’s international standing recovers after the war, specific threats to global supply chains must be taken into account, with the energy sector among the most critical (Grossman & Efron, 2016; Dekel, 2024a). Within Israel’s borders possible future threats to the energy sector could entail attacks on power plants or gas rigs, the disruption of transmission lines or pipelines, or cyberattacks on the system—whose concentration in isolated facilities creates significant vulnerability (Weinstock & Elran, 2016; Madar, 2023; Cohen, 2025). Moreover, beyond Israel’s borders, a systemic threat also looms in the form of supply denial of raw materials through trade disruption, the closure of trade routes, or direct attacks on vessels and transportation infrastructure (Dekel, 2024b).

The current focus of Israel’s energy policy is on the development of natural gas fields in the Mediterranean Sea. While this constitutes a critical component of electricity generation for the national economy, it does not ensure full energy resilience. These reserves will eventually be depleted, and moreover, reliance on fossil fuels undermines Israel’s standing in its efforts to meet the carbon-emissions reduction targets to which it has committed by 2030, as well as the targets it will be required to assume toward 2050 (Natural Gas Association & BDO, 2024; Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure, 2025b). Near-exclusive reliance on a resource dependent on isolated offshore platforms and pipelines that are vulnerable to attack creates a structural point of weakness—a lesson learned by the European Union, which suffered as a result of its dependence on Russian gas (Madar, 2023). Furthermore, natural gas is ill-suited to meet the needs of certain sectors, foremost among them transportation and heavy industry, which rely on petroleum products—an issue that has received relatively limited attention in discussions of energy-resilience strategy (in contrast to the extensive focus on electricity-grid resilience).

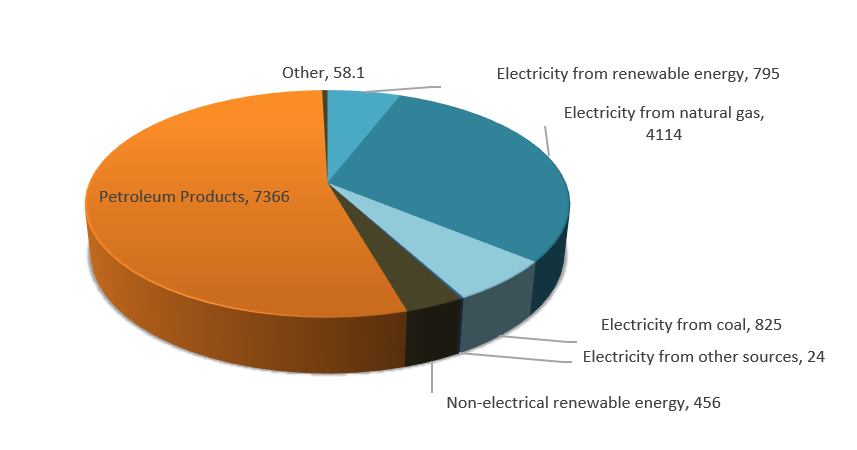

Israel’s energy economy is heavily dependent on fossil fuels, with a significant share—particularly in the transportation sector and parts of heavy industry—based on oil and its derivatives (see Figure 1). According to the forecast of the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure (2024b), despite an expected decline in demand for petroleum products (currently approximately 10 million tons per year), Israel is projected to consume close to seven million tons annually even in 2050. Despite the expansion of electric vehicle use and industrial electrification, under no plausible scenario are these trends expected to replace oil’s dominance in these sectors in the coming decades (Becher, 2024).

As an “energy island” (Weinstock & Elran, 2016; Friedman, 2021), any disruption to Israel’s oil supply chain would have immediate and direct repercussions for the entire economy. Such a disruption could result from unilateral decisions by hostile states, in contrast to isolation scenarios in other sectors that require coordination among large numbers of competing—mostly private—actors, and therefore have a lower likelihood of materialization.

Figure 1: National Energy Balance in 2024—Final Energy Consumption (ktoe)[1]

Crude oil reaches Israel from a limited number of sources, primarily from countries in the Caspian Basin—Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. Israel’s relations with these states are stable; however, the problem lies with the transit routes, which traverse Turkey, either via a pipeline terminating at the port of Ceyhan or through Black Sea ports and the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits. The deterioration of diplomatic and economic relations with Turkey has led to a Turkish goods embargo, yet oil shipments have continued. Under pressure, Azerbaijan announced that it had ceased exports to Israel, though trade has in practice continued through intermediary companies (see Schmil & Scharf, 2025). This may be attributed to Turkey’s interest in avoiding harm to its oil-exporting partners or to its reputation as a land-based energy transit hub (see Almas, 2024).

Nevertheless, under current circumstances, preparation for worst-case scenarios is required (Feldman, 2024), including the possibility of a halt to oil trade. This could take the form of preventing oil transit through Turkey’s coastline and ports, stopping tankers operating in the central Mediterranean (where Turkey has declared an exclusive economic zone for itself and Libya, contrary to established norms; Spanier & Horev, 2019), or in the Red Sea, where Turkey is establishing military bases that exert control over the chokepoint along the coasts of Somalia and Sudan (Dekel, 2024b). To this must be added the possibility of attacks on other energy infrastructures, such as cyberattacks or “mysterious” damage to subsea gas pipelines, similar to the Russian attack on the Nord Stream gas pipeline.

Indeed, Israel has been vigorously searching for new oil-export partners, yet most of these are located at considerable distances. Beyond the high costs that such distances imposes on traded oil, past experience demonstrates how easily this trade can be disrupted, as occurred with Russia due to its war in Ukraine; with the Kurdish autonomous government following a shift in Iraqi policy; with West African states experiencing frequent coups (Almas, 2023); or with eastern suppliers compelled to transit the threatened Red Sea route (Dekel, 2024b). Finally, many tankers are required to undergo transshipment at nearby Mediterranean ports in preparation for unloading in Israel, thereby reintroducing dependence on a limited number of states. A negative political shift in Greece or Italy, for example, could place Israel in a severe predicament.

The vulnerabilities do not disappear once the fuel is unloaded at Israeli ports, as the infrastructures for unloading, processing, transmission, and distribution of raw materials may themselves be subject to attack. Past examples include Hamas’ strike on the storage facilities of the Energy Infrastructure Company (EAPC) in Ashkelon in 2021 (Dekel, 2024a) and the Iranian attack on the BAZAN facilities in Haifa in June 2025, which disabled a critical component of refining operations. It was claimed that this attack brought Israel to the brink of a fuel supply crisis—ultimately averted—while the risk to the supply of cooking gas remains. This incident reveals how the economy’s reliance on only two domestic refineries, in Haifa and Ashdod, has already nearly led Israel into an energy crisis, even during wartime (Benjamin, 2025; Mustaki, 2025).[2]

Several solutions have been proposed to address this challenge, yet all suffer from significant shortcomings. First, expanding emergency oil storage capacity, which is a very costly solution and even large-scale reserves would extend capacity by only a few weeks and would certainly not ensure genuine energy independence. Second, regarding the proposal to turn toward Saudi Arabia and connect the Eilat–Ashkelon pipeline (EAPC) with the Saudi pipeline that reaches Yanbu on the Red Sea coast. Should this materialize, it would constitute an important systemic solution; however, it clearly requires normalization between the two countries, massive investments in pipeline construction, and complex solutions to mitigate the risk of oil spills along the route or in the Gulf of Eilat—an event that could devastate the local ecosystem and the city’s tourism industry. Moreover, such a pipeline would create Israeli dependence on Saudi Arabia. Moshe Becher (2024) argues that connecting the EAPC to Saudi Arabia would in fact reduce risks to the Gulf of Eilat (compared to the alternative of offloading oil from tankers at the port) and enable the flow of oil to Europe, thereby consolidating Israel’s position as a transit state. Nevertheless, all of this depends on the uncertain future of relations with Saudi Arabia, and in any case, the process would take many years to complete.

Finally, the most advanced process currently under consideration is a transition toward importing refined petroleum products (gasoline, diesel, and other fuels for industrial and household use). This move has a different underlying motivation—the desire to remove the refineries from Haifa Bay in order to promote urban and metropolitan development, reduce air pollution, and mitigate risks to residents. The closure of the BAZAN refinery (which currently supplies the majority of Israel’s petroleum products, alongside the smaller refinery in Ashdod) would reconfigure the strategic context, enabling the import of finished fuel products from a wide range of countries with operating refineries (Davidovitch et al., 2025).

According to the forecast of the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure (2024b), the global transition to renewable energy is expected to generate excess refining capacity in many refineries—primarily in the East and to a lesser extent in Europe—suggesting an adequate potential supply from a variety of potential sources. Even so, this scenario would continue to leave Israel dependent on other states (Horesh, 2020)—albeit on more diversified and therefore more stable sources—and also dependent on the security of transportation routes from those sources. If the bulk of supply originates east of Suez, this would again entail risk, as the necessary transit passes through chokepoints in the Red Sea. Accordingly, while the import option should be advanced, it should not be regarded as a comprehensive solution.

While it is possible to strengthen the protection of various infrastructures, it must be anticipated—and prepared for with a relatively high degree of certainty—that in a future confrontation the system will sustain more severe damage, whether as a result of attack, political decisions by states, or even a natural disaster such as an earthquake. Exclusive reliance on defensive measures will be insufficient in such cases, leaving Israel exposed. The guiding paradigm for the required readiness is a shift from defense to resilience—that is, recognition that some form of disruption is likely to occur, and that the system must be prepared to cope with its consequences, even under unforeseen circumstances or on unexpected scales, to endure without collapsing during the crisis and to recover rapidly thereafter. Accordingly, a national strategy for energy resilience must focus on the decentralization and diversification of the energy economy, including the oil sector. A multiplicity of “legs” provides the system with sufficient support even when one leg breaks (Eckstein et al., 2021; Grossman & Efron, 2016; Weinstock & Elran, 2016; Madar, 2023; Friedman, 2021; Cohen, 2025).

Opportunities and Constraints for Decentralizing and Diversifying the Energy Economy through Renewable Energy

As is well known, Israel is endowed with abundant solar radiation and a strong capacity to generate energy from solar sources. Among the advantages of solar infrastructures are their resilience to attack (attempts to damage photovoltaic panels require considerable effort while yielding very limited gains for an attacker) and the possibility of geographically decentralizing production facilities.This type of energy is generated, processed, and consumed entirely within Israel’s borders and therefore creates minimal dependence on external actors (aside from the supply of raw materials for infrastructure construction) (Madar, 2023).

In addition, expanding the use of renewable energy contributes to one of the most critical struggles of our time—the reduction of carbon emissions and the mitigation, and even prevention, of the climate crisis. A substantial contribution to this effort would reduce the climate-related disasters threatening Israel, from rising sea levels to extreme weather events. It would also strengthen Israel’s standing as a green and innovative state that meets the emissions targets to which it has committed in government decisions (see State Comptroller, 2020; Prime Minister’s Office, 2020) and in global forums—a soft power win for Israel in the international arena, where this issue is given pride of place (Becher, 2021).

However, three main barriers stand in the way of Israel’s ability to adopt a national strategic decision on this issue and to implement it swiftly. The first is the land constraint. Large-scale renewable energy production requires the establishment of facilities—primarily solar fields—across extensive areas. Under ideal conditions, numerous installations could be deployed on rooftops and in small sections of land between cities and villages (see Heschel Center, 2021), as well as through dual-use of agricultural land (agrivoltaics) (Friedman, 2021). Yet realizing this vision requires coordination, regulation, marketing and planning, as well as cooperation among countless landowners and property holders, and the management of planning objections (for example, on environmental or landscape grounds), among other challenges (Alterman & Tzachner, 2021; Knesset Research and Information Center, 2021; State Comptroller, 2020).

Integrated efforts to promote solar production alongside agriculture have also proven complex and suitable for only a limited range of crops, thereby constraining their overall potential. While these avenues should certainly continue to be explored, it is also necessary to acknowledge that they are lengthy and complex and are unlikely to position Israel strategically within the timeframes required to meet the 2030 targets or beyond, or to generate sufficient national energy resilience that would sever dependence on fossil fuels imported from abroad.

The optimal solution to this constraint lies in the obvious utilization of the extensive lands of the Negev, which constitute approximately 60 percent of the country’s territory. Large portions of these areas are available for the establishment of large-scale infrastructure, and they benefit from higher levels of solar irradiation than northern regions of the country, where the Mediterranean climate results in more prolonged cloud cover throughout the year. The Electricity Authority (2020) found that land reserves for solar generation in central Israel are negligible, and that 85 percent of land that is either planned or has planning potential for solar development is located in the Negev.

In this context, the second barrier arises: transmission constraints. Large-scale generation requires the delivery of energy through an extensive network of high-voltage transmission lines. This infrastructure is particularly costly and generates significant visual, ecological, and safety hazards. It occupies large land reserves that cannot be used for other purposes (except for limited agriculture) and therefore severely constrain the ability to rely on large-scale generation located far from centers of energy demand (Knesset Research and Information Center, 2021). Burying such infrastructure underground is an effective but extremely expensive solution and can therefore be implemented only in limited segments. Moreover, unauthorized construction in the Negev significantly restricts the ability to establish infrastructure efficiently in this area (State Comptroller, 2020). For these reasons, environmental organizations support the concentration of generation infrastructure in closer proximity to demand centers, thereby reducing the need for extensive transmission infrastructure (see Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel & Tasc, 2019; Heschel Center, 2021). As noted, however, these are areas characterized by high costs and stringent planning and environmental constraints, making it very difficult to operate at large scale and with speed.

Finally, the third barrier to genuine energy resilience is the transportation sector’s heavy dependence on oil-based fuels, which are difficult to substitute with electricity generated by solar installations. While batteries are increasingly used in vehicles, their adoption faces several significant challenges. First, batteries have a limited lifespan, and over time increasing problems are expected in the efficiency of aging batteries, along with associated safety hazards and severe environmental issues related to the disposal of vast quantities of batteries at the end of their life cycle. Second, and more importantly, batteries do not provide an effective solution for vehicles and heavy equipment that require high power bursts, including heavy trucks, trains, heavy engineering equipment, aircraft, ships, and the like. In addition, several heavy industries are unable to rely on electricity in place of petroleum products (Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure, 2024a, 2025b).

At this point, a national strategic initiative is proposed that could address a substantial number of the barriers outlined above, while simultaneously creating levers for development, innovation, and—most importantly—energy resilience at a level unattainable through other means. The initiative in question is the full exploitation of the Negev’s green energy potential by converting it into stored hydrogen, thereby enabling the diversion of a significant share of the national energy economy toward the use of this clean fuel.

The Opportunity Embedded in Hydrogen

Hydrogen (H₂) is the lightest element, and in its natural state it can be combusted (not fissioned—a fundamentally different process) to produce substantial amounts of energy without emitting carbon or other greenhouse gases. Although hydrogen is abundant in nature, it is extremely difficult to produce, transport, and store, and for this reason it was until recently not regarded as a significant energy resource. Over the past decade, however, it has become increasingly clear that hydrogen is likely to play a central role in the future energy economy, both due to the imperative to develop solutions in response to the climate crisis threatening humanity and as a result of cumulative technological breakthroughs that have made it possible to produce and utilize hydrogen across various domains at steadily declining costs.

Hydrogen is commonly categorized according to different “colors,” which indicate the method of production and its environmental impact. Gray or brown hydrogen is produced by separating hydrogen from fossil fuels, resulting in hydrogen fuel but offering no environmental benefit, as the carbon stored in these materials is released during the production process. The true potential and promise lie in blue and green hydrogen. Green hydrogen is produced through electrolysis, which separates hydrogen from water using renewable energy, such as solar power. Blue hydrogen, by contrast, is produced from fossil fuels, but the residual carbon is captured through various means and prevented from entering the atmosphere; for this reason, this production pathway is also considered environmentally friendly (Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2023; Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure, 2024a; Le et al., 2023; Sadeq et al., 2024).

Hydrogen also offers higher efficiency than batteries for powering heavy vehicles—such as trucks, trains, ships, aircraft, buses, and heavy engineering equipment—which require powerful energy bursts that batteries struggle to deliver. (By contrast, in private vehicles, batteries appear likely to retain a clear advantage). Hydrogen is likewise suitable for industrial applications and for energy storage at the local level. Energy generated by solar installations is most efficiently utilized when converted directly into electricity and fed into the grid, provided that it can be transmitted efficiently to consumers at the moment of generation and used effectively. As noted, during periods of peak solar irradiation it is not possible to transmit all of the energy produced; storing this energy in the form of hydrogen therefore enables its utilization outside peak hours—during nighttime or on other low-irradiation days (Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure, 2024b).

The expanding battery economy itself may also come to rely on hydrogen-based storage—for example, for rapid charging of electric vehicles, or due to the need to store energy at regional or neighborhood charging facilities, or for “seasonal storage,” requirements for which the use of massive battery installations is neither efficient nor safe. In sum, hydrogen—whether as a stand-alone energy carrier or as part of an extended supply chain within the various energy sectors—is a central component that can provide both economic energy efficiency and effective mitigation of the climate crisis. It is not intended to replace the use of natural gas or solar energy in the electricity grid, but rather to function as a complementary element—either within the energy supply chain or as a solution for specific segments for which gas or electricity alone offer no adequate response.

The conversion of various sectors of the economy to hydrogen is neither simple nor inexpensive; however, the means to do so already exist, and the global economy is advancing decisively toward this objective—in Japan, Australia, Germany, and elsewhere. In the regional context as well, Saudi Arabia is establishing massive infrastructure for the production of green hydrogen as part of the NEOM project. The financial scale of hydrogen infrastructure projects worldwide has increased eightfold since 2021 and is now estimated at approximately USD 680 billion (Hydrogen Council, 2024). This transformation offers tremendous opportunities for technological and infrastructure deployment that are expected to drive broad-based growth. The principal challenge currently facing this transition is the cost of green hydrogen, which remains higher than that of petroleum products. Nonetheless, the prevailing technological trend is toward declining costs, driven both by continuous technological innovation in the field and by the now established deployment of infrastructure and market development, which enable market mechanisms within the sector to mature and reduce costs accordingly (Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2023; Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure, 2024a; see also Mallapragada et al., 2020). It is also noteworthy that Israel’s hydrogen innovation ecosystem has been developing in recent years, with examples including companies such as H2PRO, GenCell, Electric Global, H2 Clarity, and others.

The Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure (2024a) has recently examined this issue and formulated a national hydrogen strategy, whose main components are as follows:

(1) preparation for the development of a hydrogen market to begin immediately, both in order to integrate into the global trend and as part of a future regional hydrogen ecosystem in the Middle East; (2) investment in hydrogen-related research and development, with the aim of leveraging Israel’s innovation capacity to achieve technological breakthroughs in the field; (3) a cautious approach, given that the widespread adoption of hydrogen use depends on multiple factors, some of which involve reliance on projected technologies that have not yet been developed, rendering the future of hydrogen uncertain; (4) accordingly, preparation for limited use of hydrogen (a minimum scenario), unless technological conditions change and enable expansion (a maximum scenario), particularly in light of the economy’s relatively low suitability for hydrogen’s advantages—Israel has a limited heavy industry base, and its transportation infrastructure is not extensive, in contrast to large industrialized economies such as China, the United States, or the countries of the European Union.

The “Hydrogen Valley” in the Negev

Unlike oil or gas wells, where the resource is located beneath the surface and extraction requires primarily the establishment of pumping infrastructure, hydrogen production is more complex. Nevertheless, given the requisite infrastructure, it may be argued—by way of analogy—that the Negev contains a “well” of green hydrogen fuel—a kind of “Leviathan reservoir” in the desert (analogous to the Leviathan natural gas field in the eastern Mediterranean). Although hydrogen can be produced from multiple sources, only the Negev offers the potential for establishing an infrastructure complex of sufficient scale.

This chapter proposes a strategic framework outlining the possibilities and opportunities for such development, while recognizing that each of its components requires further in-depth research to assess feasibility and implications, alongside detailed implementation planning. The framework defines an optimal regional development approach, identifies land-use potential (both within existing plans and in areas not yet planned or assessed), highlights potential hydrogen applications (some of which have been examined in depth by governmental bodies and others that have not), and presents a selection of emerging innovative technological opportunities—acknowledging that many more are likely to arise as the national initiative takes shape. The conceptual linkage between the full spectrum of possibilities, on the one hand, and the pressing need, on the other—stemming both from the geopolitical threat that has not been sufficiently examined by state institutions and from the unique opportunity for regional development in the periphery—leads to the strategic conclusion regarding the importance of adopting the maximum hydrogen scenario and focusing on the establishment of a “Hydrogen Valley” in the Negev.

A “Hydrogen Valley” is the globally accepted development model, describing a regional-scale system that integrates production, transportation, distribution infrastructure and end users, alongside research and development that supports all segments of the value chain. The underlying premise is that the relative difficulty of transporting hydrogen over long distances necessitates the concentration of this ecosystem within a defined area in order to maximize the benefits of a semi-closed system. Initial steps toward establishing hydrogen valleys have already begun in Israel, in the Eilat–Eilot region and in Dimona and the eastern Negev (Dekel, 2022). However, all of these initiatives remain inherently dependent on substantial state backing and budgetary support for the deployment of initial infrastructure. From a broader perspective, the Negev can be viewed as a single region divided into several interlinked “valleys”—Eilat, Dimona, and Ramat Negev—and accordingly, their potential is assessed as one integrated regional complex.

In the Negev—Israel’s most solar-rich and land-abundant region—several large renewable energy facilities are already in operation, foremost among them the Ashalim solar-thermal complex. Much larger fields are planned and expected to be established in the coming years (see Planning Administration, 2021; Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure, 2025a), including the expansion of Ashalim, Dimona South, the expansion of Tze’elim, Timna and additional sites in the Arava region, Hatrurim, Hatzerim, and others (amounting in total to approximately 20,000 dunams). Two additional mega-projects are currently at preliminary planning stages: “Green Sdom” on the lands of the Dead Sea Works, and the Oron–Zin field, which is undergoing statutory planning. The latter is expected to cover an area of up to 110,000 dunams and to generate tens of thousands of megawatt-hours of solar energy—making it one of the largest solar fields in the world. In addition, numerous small- and medium-scale fields that have been established or are expected to be established across the Negev are projected collectively to generate hundreds of thousands more megawatt-hours. These include installations within the jurisdictional areas of communities and cities, in areas to be regulated within Bedouin localities, on the plains surrounding Neot Hovav and the Negev Nuclear Research Center (Dimona), and particularly within military installations and extensive firing zones, which together hold significant potential spanning tens of thousands of dunams (Electricity Authority, 2020). To this may be added fields that could be established in southern Jordan and especially in central Sinai, close to the Israeli border, through joint investment, with energy sold to the Israeli side. In a more optimistic vision, one could also include the import of hydrogen from NEOM facilities—the massive Saudi hydrogen hub currently under development.

Among the factors that hinder or delay this vision, the first is the constraint of available capital for construction. This challenge could be addressed if the state were to designate the initiative as a national priority and decide to provide financial support—whether through direct grants to developers or by subsidizing land and development costs—as well as by streamlining and accelerating planning and permission processes. Second, opposition has emerged from environmental organizations that view some of the proposed fields as visual and ecological nuisances, particularly in the heart of the desert, which they regard as a space of tranquillity and serenity and as a primordial landscape that should be preserved (Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel & Tasc, 2019). These arguments should not be dismissed lightly. Nevertheless, it can be argued convincingly—and planning committees can be guided accordingly—that the Negev is sufficiently vast and constitutes 60 percent of the country’s territory. While this area cannot meet all the needs of the energy economy due to the presence of firing zones, nature reserves, and other land uses, it is nonetheless large enough to allow, with appropriate care and balance, the establishment of several facilities that serve both the national interest and environmental objectives in the context of the climate challenge.[3]

Third, and perhaps most importantly, as explained above, there is the challenge of transmitting energy to the main centers of demand in central Israel. Only recently was the 400 kV transmission line connecting Dimona to the center completed, and even this line is not expected to withstand peak energy loads—certainly not after the majority of planned projects are brought online. National Outline Plan 41, which awaits government approval and addresses the deployment of energy infrastructure, is based on low and outdated national emissions targets, does not reflect the technological breakthroughs of recent years, and fails to address the importance of energy resilience in light of current geopolitical threats. Consequently, the plan does not adequately regulate the required transmission network. In practice and in planning terms, the Negev is not allocated sufficient generation areas or an adequate transmission network—either in existing plans or in the outline plan that has remained unapproved since 2021—and this has led to the rejection of a substantial share of entrepreneurial applications to connect solar facilities in the Negev to the grid (on the basis of network constraints—to a far greater extent than in any other region) (Knesset Research and Information Center, 2021).

At this point, the storage of surplus energy in the form of hydrogen becomes relevant, capturing energy that cannot be transmitted directly through the electrolysis of water (or through emerging methods for direct extraction from water). To enable this, the state would need to establish a major water conveyance system, including a new desalination facility in the southern coastal plain, to transport water to a series of large reservoirs in the eastern Negev. This conveyance system—whose construction and operating costs, including the energy required for pumping, would be offset by energy production—would enable the generation of hydrogen from water, alongside the production of oxygen (for various industrial uses). In parallel, it would allow for a significant expansion of agriculture in the eastern Negev, the upgrading of urban parks and landscaping for hundreds of thousands of residents, and the development of large-scale tourism projects around expanded oasis areas, including the Yeruham Lake, Dimona, Golda Park, and the Be’er Sheva River.[4]

New technologies developed by Israeli companies will make it possible to produce additional hydrogen from novel sources. For example, one technology enables the melting of mixed municipal waste and its conversion into green hydrogen on the one hand and a solid material on the other, which can be used in construction. The establishment of such facilities in Negev cities and at existing national landfill sites located in the region (Afa’a and Dudaim) would allow the production of thousands of tons of hydrogen per year (estimated at more than 2,000 tons annually per small city), while also providing a clean, environmentally sound, and economically viable alternative to waste burial. Another emerging technology enables the production of hydrogen from natural gas, while capturing the residual carbon and chemically binding it to phosphogypsum for the production of limestone. In this way, a polluting gas is converted into blue hydrogen (estimated at approximately 100,000 tons per year), in a facility to be established adjacent to the phosphogypsum stockpiles of the Dead Sea Works in the eastern Negev.

A rough estimate indicates that combining green hydrogen produced from solar installations (for estimation purposes, once facilities covering approximately 200,000 dunams are established, roughly half of this area could be utilized to produce about 300,000 tons of hydrogen per year) with hydrogen derived from waste and blue hydrogen produced from natural gas (an additional approximately 100,000 tons per year) would yield a total of close to half a million tons annually in the Negev. This is not intended as a precise calculation, but rather as an order-of-magnitude estimate of what could be achieved on the basis of defining a national target.

If an “either–or” approach is not adopted (either large solar installations in the Negev or a proliferation of small installations in central Israel), but rather a “both–and” approach, it would be possible to allocate most of the Negev’s infrastructure potential to hydrogen production, while the remaining facilities would supply electricity directly to the national grid. What would such a large quantity of hydrogen be used for? According to the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure (2024a), under a maximum scenario it would be possible to utilize approximately one million tons per year to power 40 percent of heavy vehicles (heavy trucks and buses), supply about one-quarter of industrial energy consumption (across 15 large factories), and meet most of the aviation and maritime sectors’ needs through synthetic aviation fuels (SAF). If achieved as a national target, this level would enable genuine and substantive diversification in these complex sectors.[5]

The Government of Israel has recently identified the potential inherent in this vision and, through a government resolution, allocated an initial NIS 20 million for the establishment of a Hydrogen Valley, conceived as a regional ecosystem involving local authorities (led by Dimona and joined by additional authorities in the eastern Negev). The launch of the hydrogen ecosystem in the Negev will begin with support for pilot projects that will enable experimentation and gradual refinement, assessment of the efficiency of available technologies and their applicability, while assisting in mitigating the risk associated with entrepreneurial investment in this new frontier. The initial stage will involve the establishment of a network of hydrogen refueling stations along the Eilat–Be’er Sheva–Haifa corridor, followed by the gradual replacement of heavy vehicle fleets and heavy engineering equipment throughout the region with hydrogen-powered alternatives (a process that is desirable and, in the early stages, necessary with state support in the form of subsidies for vehicle procurement and station construction, as without such support the infrastructure required for market activity in this new sector cannot be established).

The next step will be the creation of extensive urban microgrids in the cities of the eastern Negev, based on hydrogen, enabling urban carbon neutrality for more than half a million residents. Within the urban system, hydrogen will be converted in local facilities into electricity for residential use, industry, and the charging of private electric vehicles, or for powering hydrogen-fueled buses. Similar applications will be implemented at IDF bases and other security installations, which will in practice be disconnected from the national electricity grid in favor of local energy independence. In parallel, the planned railway line between Be’er Sheva and Eilat will operate on the basis of hydrogen-powered locomotives, as will other large facilities, including Ramon Airport and others.

Major industries located in the Negev would undergo extensive conversion to hydrogen-based processes—among them the Dead Sea Works, the Negev Nuclear Research Center (Dimona), and others. With state encouragement, additional large industries would relocate from central Israel to the eastern Negev, where they would benefit from cheaper land prices, access to subsidized green energy in the Negev, and the advantage of marketing their products abroad as carbon-footprint–free, thereby qualifying for exemptions from environmental tariffs, which are expected to rise significantly in the coming years. One particularly important initiative to be examined is the establishment of a southern green cement plant. Existing cement plants are among the most polluting industrial facilities and major contributors to carbon emissions, due to the massive kilns required for cement production. The need to establish an additional cement plant in the Negev was already identified by the Hershkovitz Committee (Interministerial Committee for Promoting Competition in the Cement Industry, 2013), as part of efforts to reduce construction costs and enhance sector resilience by avoiding dependence on imported cement. The hydrogen “well” in the Negev creates an opportunity to produce hydrogen-based green cement and to further strengthen resilience in the construction sector (see Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2023; Bacatelo et al., 2024).

Additional industries that would derive significant advantage from access to green and blue hydrogen—and that would also generate broad regional development spillovers—include producers of green ammonia (which can be transported by tanker from the port of Ashdod to European ports and reconverted there into green hydrogen), as well as producers of clean aviation fuel, namely synthetic aviation fuels (see Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure, 2024c). Existing Israeli technological developments also make it possible to store hydrogen in the form of a dry powder—a product that enables efficient and safe energy storage for powering engines at sites not connected to the grid, such as construction sites, military camps, or other remote locations.

Another major energy consumer, whose future growth is expected to be exponential, is data centers, which are required to support the vast markets of artificial intelligence, cryptocurrency, and the entire intercontinental internet infrastructure. For cooling purposes, large data centers consume enormous amounts of energy, and worldwide they are increasingly required to demonstrate efforts to reduce their carbon emissions. With state support and encouragement, the hydrogen reservoir in the Negev could be leveraged for the establishment of a large-scale data center complex in Be’er Sheva, which would serve as an anchor for substantial growth in technology companies that depend on proximity to such facilities in order to access high levels of computing power.

Finally, the establishment of a national research and development center for energy and storage in the heart of the Negev would create the “nerve center” of the entire Hydrogen Valley (as proposed, for example, by the Or Movement – the Guttsman Laboratory for the Future of Israel, and the Municipality of Dimona; Dekel, 2022). This would enable the development of an infrastructure hub linking production, transmission, consumption, and research within a large-scale “living laboratory,” enhancing capabilities and generating a leading edge of knowledge for a world increasingly hungry for Israeli innovation, particularly in the context of the climate crisis.

Conclusion

Geopolitical threats to Israel are steadily intensifying, assuming evolving and diverse forms, among which threats to the energy sector occupy a distinct and critical place. Current trends point to a growing threat from Turkey, even if primarily over the long term. Turkey’s control—amid steadily deteriorating relations—over Israel’s principal oil trade routes constitutes a critical vulnerability, whether through pipelines traversing its territory, overseas military bases along the Red Sea, or its capacity to attack, directly or via proxies (overtly or covertly), oil infrastructure as well as other components of the energy network within Israel’s borders. Building resilience in Israel’s energy economy against this threat, and against similar ones, depends on decentralizing and diversifying energy sources beyond the country’s heavy reliance on natural gas. However, the required transition to renewable energy is fraught with physical, economic, and regulatory barriers and, in any case, does not provide a satisfactory solution for the transportation and heavy industrial sectors, whose dependence on oil is high and is expected to remain so for a long time.

The systemic response proposed here, even if not comprehensive, is to view hydrogen production as a central component in building this resilience: transforming the Negev into Israel’s energy hub, centered on a system for producing and utilizing hydrogen generated from renewable energy and water (green hydrogen) or from natural gas and waste, with carbon capture to prevent its release into the atmosphere (blue hydrogen). A Hydrogen Valley in the Negev would enable the production of clean, carbon-free fuel for energy-intensive segments of the heavy-truck, bus, rail, maritime, aviation, and heavy industrial sectors. Such a system would embed resilience within the energy economy in the event of disruption—whether due to attacks on infrastructure, embargoes, blockades, or even natural disasters—while also positioning Israel to advance toward global leadership in the fight against the climate crisis, anchoring it at the forefront of this critical technological domain and strengthening its role within the emerging regional hydrogen ecosystem alongside its neighbors.

This strategic perspective broadens the prevailing view regarding the nature of the threats, the urgency of addressing them, and the manner in which they should be weighed within the technical and economic debate over the appropriate level of investment in hydrogen. It argues that discussions of the future of the energy economy must assess which innovations are likely to emerge, while also considering how they can be actively brought about. In this sense, the perspective reflects a distinctly Israeli approach grounded in confidence in innovation—one that identifies opportunity and acts to realize it, even when modes of implementation have not yet been fully tested and the requisite technologies have not yet fully matured. Thus emerges a call to regard the “maximum scenario” recently defined by the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure as the “necessary minimum” for achieving adequate national resilience, as well as a call to leverage the Hydrogen Valley as a powerful engine of regional growth for the Negev and for the economy as a whole.

**

The article was written in collaboration with the Gottesman Lab for the Future of Israel and the Or Movement (Within the framework of the Or Movement, the author accompanied the Municipality of Dimona in a strategic assessment of the hydrogen sector as a growth engine for the city.)

Sources

Almas, D. S. (2023, October 2). After the coup in Gabon: Where will Israel now source its oil? Globes. https://tinyurl.com/2wh4ynx6

Almas, D. S. (2024, May 5). Oil exports to Israel via Turkey continue despite the embargo: These are the reasons. Walla. https://tinyurl.com/57jh6pv9

Alterman, R., & Teschner, N. (2021). Grounded renewable energy: Regulatory barriers regarding land-use and planning in Israel in comparative perspective. Technion – Center for Urban and Regional Studies. https://tinyurl.com/5cfahme9

Bacatelo, M., Capucha, F., Ferrão, P., Margarido, F., & Bordado, J. (2024). Carbon-neutral cement: The role of green hydrogen. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 63, 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.03.028

Behar, G. (2021). Israel and the international climate change arena—A matter of national security. In K. Michael, A. Tal, G. Lindenstrauss, S. Bokchin-Peles, D. Hanin, & U. Weiss (Eds.), Environment, climate, and national security: A new front for Israel (pp. 67–77). Institute for National Security Studies.

Behar, M. (2024). Diversifying Israel’s oil supply sources. Hashiloach, 39. https://tinyurl.com/rd3ucez6

Benjamin, I. (2025, September 15). Winter is approaching, and cooking and heating gas may be insufficient for households. TheMarker. https://tinyurl.com/3jre79wd

Cevic, S. (2025, October 2). Beyond Gaza: The strategic fault lines in Turkey–Israel relations. Arab Center Washington DC. https://tinyurl.com/3x5885f2

Cohen, E. (2025). Structural vulnerabilities and resilience of Israel’s energy sector during security emergencies. Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/15567249.2025.2559944

Cohen Yanarocak, H. A. (2025a, May 31). The Turkish crescent: A new strategic challenge for Israel. Israel–Africa Relations Institute. https://tinyurl.com/2p8ym2wb

Cohen Yanarocak, H. A. (2025b, July 7). The cold war between Israel and Turkey has begun. Israel Center for Grand Strategy. https://tinyurl.com/muhjjr86

Davidovitch, N., Rubin, O., Olos, T., & Neiman, N. (2025, July). Position paper: Accelerating Israel’s transition to alternative energy following damage to BAZAN—Policy steps for realizing a new vision for the energy sector. National Institute for Climate Policy, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. https://tinyurl.com/yenzryh4

Dekel, T. (2022). Developing growth engines in the energy and robotics sectors in Dimona. Municipality of Dimona & Or Movement.

Dekel, T. (2024a). Hamas and the new great game. Strategic Assessment, 27(1), 3–15. https://tinyurl.com/mwm7spaa

Dekel, T. (2024b). Chokepoint: Great Power Infrastructure Competition in the Red Sea. Strategic Assessment, 27(4), 3–17. https://tinyurl.com/uejw2a94

Eckstein, Z., Somkin, S., & Axelrad, H. (2021). A strategy for optimal planning of the electricity sector. Policy Paper 2021.03, Aaron Institute for Economic Policy. https://tinyurl.com/2y22myvt

Electricity Authority. (2020, August 10). Raising renewable electricity generation targets for 2030. https://tinyurl.com/2s38whw8

Epstein, J. (2025, June 25). Turkey and Israel—Cooperation through gritted teeth. Turkeyscope, 9(3). Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies, Tel Aviv University. https://tinyurl.com/3rsy38au

Feldman, N. (2024, January 2). Israel’s oil trap: Will Erdoğan turn off the tap? TheMarker. https://tinyurl.com/2hjx8hzc

Friedman, G. (2021). Renewable energy—The key to national energy resilience. In K. Michael, A. Tal, G. Lindenstrauss, S. Bokchin-Peles, D. Hanin, & U. Weiss (Eds.), Environment, climate, and national security: A new front for Israel (pp. 199–211). Institute for National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/4vst9myx

Grossman, G., & Efron, Y. (Eds.). (2016). Environment and energy: Energy supply security in Israel—Summary and recommendations of Energy Forum 37. Samuel Ne’eman Institute. https://tinyurl.com/4fu5mets

Heschel Center. (2021). NZO: 95% renewable electricity in Israel by 2050. https://tinyurl.com/ym4av34v

Horesh, H. (2020, June 16). The censored McKinsey report: “Evacuating Haifa Bay factories will cost NIS 18 billion—too expensive.” TheMarker. https://tinyurl.com/3n4jn6bm

Hydrogen Council & McKinsey & Company. (2024). Hydrogen Insights 2024. https://tinyurl.com/mtk9fzfe

Interministerial Committee for Promoting Competition in the Cement Industry (Hershkovitz Committee). (2013). Structural changes and increasing competition in the cement industry: Findings and recommendations. https://tinyurl.com/mumjbx5u

Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Steering Committee for coping with the climate crisis. (2023). Position paper No. 3: Hydrogen fuel. https://tinyurl.com/4aytccv4

Knesset Research and Information Center. (2021, December 7). Renewable energy in Israel—Background and issues for discussion (update). https://tinyurl.com/2rb4au7p

Lazimi, N. (2025, October 10). The Turkish test: What should Israel beware of in a Trump agreement? Walla. https://tinyurl.com/yc4sk2wj

Le, P. A., Trung, V. D., Nguyen, P. L., Phung, T. V. B., Natsuki, J., & Natsuki, T. (2023). The current status of hydrogen energy: An overview. RSC Advances, 13(40), 28262–28287. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA05158G

Lindenstrauss, G., & Daniel, R. (2024, May 19). Turkey–Israel relations at a dangerous turning point. INSS Insight No. 1853, Institute for National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/3ksyzz8d

Madar, D. (2023). Energy resilience in Israel—Centralized versus decentralized electricity grids: A risk review. SP Interface. https://tinyurl.com/bd2k4b4a

Mallapragada, D. S., Gençer, E., Insinger, P., Keith, D. W., & O’Sullivan, F. M. (2020). Can industrial-scale solar hydrogen supplied from commodity technologies be cost competitive by 2030? Cell Reports Physical Science, 1(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrp.2020.100174

Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure. (2024a, February). Hydrogen strategy: Guiding principles and decision points. https://tinyurl.com/yxtzkzhy

Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure. (2024b, June 16). The future of Israel’s fuel economy—A strategic study. https://tinyurl.com/3chnd3dx

Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure. (2024c, July 11). Policy paper on sustainable aviation fuels. https://tinyurl.com/3mww7y58

Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure. (2025a, January). Update document to the “2030 Renewable Energy Roadmap.” https://tinyurl.com/2jmyrard

Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure. (2025b, April 9). Interministerial committee on natural gas policy and strengthening energy security—Draft report for public comment. https://tinyurl.com/3s5bhpxu

Mustaki, A. A. (2025, July 15). Refineries warn of a severe diesel shortage; the Ministry of Energy insists there is no problem. Calcalist. https://tinyurl.com/42b2t2c7

Natural Gas Association & BDO. (2024). The natural gas economy in Israel 2024—Energy security in Israel 2024. https://tinyurl.com/y8dkswtr

Planning Administration. (2021, November 22). National Outline Plan TAMA/41—Energy infrastructure. https://tinyurl.com/37tspptr

Prime Minister’s Office. (2020, October 25). Promoting renewable energy in the electricity sector and amending government decisions (Government Decision No. 465). https://tinyurl.com/mr3477z3

Sadeq, A. M., Homod, R. Z., Hussein, A. K., Togun, H., Mahmoodi, A., Isleem, H. F., Patil, A. R., & Moghaddam, A. H. (2024). Hydrogen energy systems: Technologies, trends, and future prospects. Science of the Total Environment, 939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173622

Schmil, D., & Scharf, A. (2025, June 3). According to official data—Azerbaijan has stopped oil exports to Israel. The truth is somewhat different. TheMarker. https://tinyurl.com/dam86f36

Spanier, B., & Horev, S. (2019, December 23). How Turkey could block Israel in the Mediterranean. Ynet. https://tinyurl.com/r95x83nu

Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel & Tasc. (2023). Formulating a strategy for a green electricity grid in Israel. https://tinyurl.com/cjn7ukje

State Comptroller of Israel. (2020). Annual report 71A: Promoting renewable energy and reducing dependence on fossil fuels. https://tinyurl.com/2jcw25x4

Weinstock, D., & Elran, M. (2016). Securing Israel’s electricity system: A proposal for a grand strategy. Memorandum No. 152, Institute for National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/buazcym2

________________________

[1] ktoe –equivalent to a ton of oil. Total energy depicted = 13,639 ktoe. The figure is based on processing data from Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS): Energy Balance (detailed by products), 2024, thousand ktoe.

The breakdown of the electricity sector’s energy balance by source was processed on the basis of: Electricity Authority (2025), Report on the State of the Electricity Sector for 2024, Table 1.2: National generation. This breakdown is an approximate estimate, since total generation data are reported in TWh, whereas the national energy balance data presented in the figure are measured in ktoe. The metrics were assumed to be comparable, taking into account each component’s share of total electricity generation.

[2] It should be noted that researchers in the field warned precisely of such scenarios years in advance (see, for example, Weinstock & Elran, 2016).

[3] The Electricity Authority (2020) identified that 85 percent of the land reserves suitable for new solar installations are located in the Negev, with a significant share in the western Negev, based on agrivoltaic applications and fields within the jurisdictional areas of communities. Additional land potential that has not yet been sufficiently examined exists in “landlocked” areas within large industrial zones (such as the Rotem Plain), in unused mining areas, in firing zones where no conflicting activity takes place, along the perimeters of security installations such as airfields and testing grounds, and in dispersed Bedouin areas designated for evacuation and formal regulation. These areas are not currently being assessed, as the potential of sites more convenient for development has not yet been exhausted; however, over the long term they constitute a highly significant land reserve.

[4] It is important to note that the volume of water required for the production of green hydrogen is not expected to be significant at all when compared to national water consumption (Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2023).

[5] To provide a sense of scale, under current technology it is possible to produce approximately three tons of hydrogen per year from one dunam of photovoltaic panels, with a water consumption of about 27 cubic meters. This quantity of hydrogen is sufficient to fuel between one hydrogen-powered truck and one-third of a truck per year, depending on vehicle weight and mileage. It should be noted that hydrogen use may take the form of a hydrogen internal combustion engine or, alternatively, an electric motor powered through rapid charging based on a hydrogen fuel cell. If by 2050 Israel has approximately 200,000 medium and heavy trucks (over 3.5 tons), then powering 40 percent of them with hydrogen would require between 100,000 and 150,000 dunams producing green hydrogen. Blue hydrogen could, of course, be incorporated into the supply, thereby enabling this target to be achieved with roughly half the land area. Under the maximum scenario, the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure estimates that 278,000 tons of hydrogen would serve the transportation sector at these scales.