Strategic Assessment

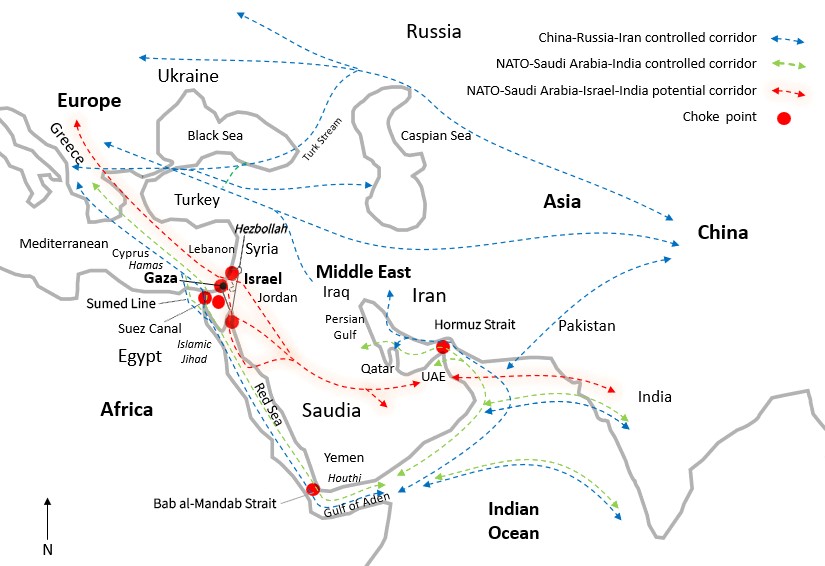

This article examines the factors that currently shape the attitude of countries around the world toward Israel in its struggle against Hamas, with a focus on energy. This mapping describes the enormous significance of energy in the contest taking place between the great powers in the background of the conflict, principally China, Russia, the US, and the NATO countries. Other constellations of alliances with a variety of players include Iran and the Shiite axis, Saudi Arabia and the Sunni axis, Turkey, and Greece. This analysis focuses on energy resources, energy corridors, and geographic “choke points”—a matter of utmost strategic significance in what is being referred to as “the New Great Game”—a cold war-style struggle for control of the Asian continent and the land passages crossing it or the sea routes surrounding it.

Keywords: Hamas, Gaza Strip, Russia, China, geopolitics of energy, Belt and Road Initiative, India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC)

When elephants dance, the grass gets beaten (Heiduk, 2022, p. 1).

Introduction

What is shaping the attitude of countries around the world toward Israel in its struggle against Hamas? In the days after October 7, 2023, Israel encountered a variety of responses in the global arena, some of which came as a great surprise, causing the collapse of conceptions and the beginning of new thinking about Israel’s relations with various countries. Israel benefited from strong support from a number of Western countries, above all the US, which put its military power squarely behind Israel. In parallel, as expected, the axis of resistance countries, led by Iran, denounced Israel before it had even responded to the war crime committed against it. No less powerful dramas took place between these two polar opposites. In contrast to past clashes, voices in some Muslim countries, among them Saudi Arabia, condemned Hamas. Great powers Russia and China chose to condemn Israel, even though they had no clear ideological affiliation whatsoever in the conflict (e.g., Einav, 2023; Feldman & Mil-Man, 2023).

Hamas is willing to embark on a dangerous conflict with Israel not because it hopes for a military victory, but rather because its main objective is to undermine Israel’s status in the international theater in order to promote the organization’s long-term goals (Gazit, 2014). The international theater is a critical theater of warfare for Israel, which cannot win in the struggle against Hamas without a good understanding of the war’s underlying causes. This article therefore analyzes one of the most important aspects affecting the geopolitical and economic interests of a country— the geopolitics of energy—and thereby determining, to a large extent, its position toward Israel’s conflict with Hamas. By mapping the global power struggles for control over energy resources and the energy corridors, referred to as the “New Great Game” in Central Asia and the Middle East, this analysis focuses on the specific array of interests that has recently surfaced around Israel. From these interests, one can understand the role that Hamas’s patrons have designed for it and one of the reasons why they have provided Hamas with large-scale aid over the years. Finally, this article elucidates the reasons why various countries have backed Hamas, even if they have not actively supported the organization economically or militarily. This support is crucial to understand, given the significant threat Hamas poses to Israel. It underscores the necessity of Israel to carefully examine the statements of these countries and identify who is standing behind them and their motives.

This article begins by reviewing the literature on the geopolitics of energy both globally and in Israel before and during the current war in Gaza. It then examines the energy alliances and conflicts between the Middle East, Russia, and the US; the attitude of China to the entire Eurasian area; and finally other countries and their attitude to the array of alliances in the framework of the “New Great Game.” The sources include professional geopolitical literature, current newspaper reports, and official plans and documents of international organizations.

The Geopolitics of Energy Corridors

Energy is a crucial element in the economy of every country, whether the country imports energy and must secure a stable supply or exports energy and needs to ensure regular, safe production and high prices. Apart from coal (which cannot be used for transportation and causes severe environmental damage), the main fuels used in global economies are oil and natural gas. Recently there has been a slow expansion of the use of solar energy, with efforts underway to develop technologies and infrastructure for its efficient use in the transportation industry through storage in batteries or conversion of solar energy to hydrogen and ammonia fuel. Oil and gas deposits and areas with abundant sunshine are not typically located near the most consumers, such as in densely populated industrialized areas with highly developed economies or rapidly developing economies like Europe, China, and India (its extensive oil reserves make the US an exception). As a result, control over the energy corridors through which oil, gas, and soon hydrogen and ammonia are transported from producers to consumers has become one of the crucial aspects in global geopolitics, with many arguing that it is the most crucial of all (Milina, 2007; Månsson, 2014; Johannesson & Clowes, 2022).

This is the reason maritime straits, through which most of the world’s energy and trade goods flow, are constant sites of struggle. The Strait of Hormuz connects the oil and gas-rich Persian Gulf to the Indian Ocean and is a theater of constant conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia. The Strait of Malacca connects the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea and is crucial for China. The Bab al-Mandab Strait connects the Gulf of Aden in the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea, and from there, through the Suez Canal, to the Mediterranean Sea and Europe. Through these three narrow passages, a significant proportion of global trade in energy and goods passes, and they can become choke points if they are militarily blocked or threatened. Similarly, the energy pipelines passing through transit states are also prone to threats along their long routes.

Controlling or guarding of the energy corridors determines a country’s economic power, its independence during a crisis, and its geopolitical leverage over other countries that depend on these corridors for energy supply or marketing. Any power or alliance of countries, such as the European Union (EU), is bound to safeguard its control of the relevant corridors by signing bilateral agreements, fostering international energy markets and institutions, using military means and/or direct control, or indirectly through proxy countries or organizations. A major power must ensure that the routes it needs are safeguarded or devise alternative routes. It must also be able to block the routes of its enemies when necessary (Rodrigue, 2004; Milina, 2007; Masuda, 2007; Pascual & Zambetakis, 2010; Månsson, 2014; Campos & Fernandes, 2017; Hao et al., 2020).

Development of energy corridors is a complex and expensive process. In part, it requires the laying of special pipelines stretching for hundreds and thousands of kilometers, storage facilities, pumping stations, and sea passages, the construction of ports, and the digging and maintenance of canals. Once the corridor is established, its security must be maintained, and payments must be made to the transit countries. For this reason, and due to the strategic importance of buying or selling energy, establishing a corridor between countries creates a significant alliance. A corridor project is likely to resolve disputes between countries and enhance cooperation between them, but the opposite is also true—a dispute could hinder a potential infrastructure project connecting countries (Masuda, 2007; Hao et al., 2020). To illustrate the first possibility, in the 1970s, during the Cold War, the Soviet Union built gas lines to West Germany to strengthen relations between the countries and create strategic dependence (Schattenberg, 2022). Led by Russia, this process has continued in recent decades and has proven to be a great success, making Russia an “energy superpower” (Milina, 2007, p. 30). Many European countries now heavily rely on Russian gas (Campos & Fernandes, 2017), despite the conflict in Ukraine (which will be discussed later).

The Geopolitics of Energy in Israel—A Historical Perspective

For most of its history, Israel’s energy projects have been hindered by conflict. The Negev, in the south of Israel, is a narrow strip of land that blocks one of the world’s most important land bridges that links Asia to Africa and the West, as well as the Port of Eilat on the Red Sea to ports on the Mediterranean Sea. This territorial strip has always been of great strategic importance and has been the cause of repeated conquests by Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, Greece, Rome, the Arabs, the Ottoman Empire, and the British Empire (to name a few). Even before the State of Israel was established, David Ben-Gurion recognized the strategic importance of the Negev and put a lot of effort into settling the desert in order to convince the UN to include it in Israel’s national territory. In the War of Independence in 1948, both Ben-Gurion and Israel’s enemies saw control of the Negev as the “core of the conflict” (Asia, 1994). Israel’s successive wars have also centered around the marine-land corridor. The 1956 war, which pitted Egypt against Israel, Britain, and France, started after Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal and prevented Israeli ships from passing through. The British and French supported Israel in an (unsuccessful) attempt to regain control of the Suez Canal. In May 1967, Egypt blockaded the Straits of Tiran at the Gulf of Aqaba, preventing Israeli passage through the Suez Canal; Israel responded with war and eventually reached the Suez Canal. In the Yom Kippur War in 1973, the Egyptians regained control of the area, giving Israel passage through the Straits of Tiran and the Suez Canal only in 1977 when the peace treaty was signed between Israel and Egypt.

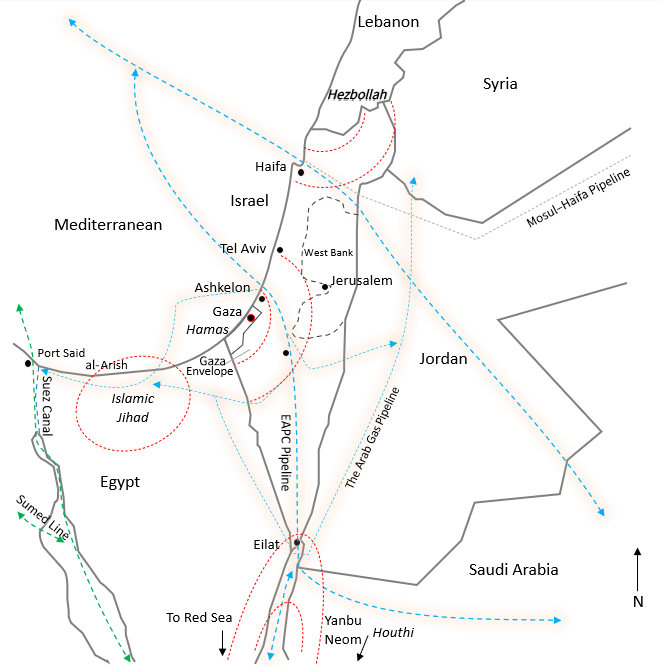

Only until recent decades, Israel had been reliant on energy imports from distant countries, due to the conflicts with its neighbors, even though many of them are among the world’s largest oil and natural gas producers. Israel’s efforts to become a transit country have also been unsuccessful. The oil pipeline from Mosul in Iraq to Haifa Port, built by the British in the 1930s, was abandoned in 1948 during Israel’s War of Independence, with its remnants looted and sold for scrap metal. Similarly, the Eilat–Ashkelon oil pipeline, constructed in the 1970s through an Israeli–Iranian partnership, declined in use. Iran utilized this pipeline to circumvent the Egyptian Suez Canal (and another Egyptian route, the Sumed pipeline, which connects the ports in the Gulf of Suez to the Port of Alexandria on the Mediterranean Sea). Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, when Iran became staunchly hostile to Israel, the pipeline’s usage significantly decreased, only increasing in recent years as a route for oil from Azerbaijan and several other countries. The Arab gas pipeline, connecting Egypt to Jordan and Syria from northern Sinai to Aqaba, included a substantial detour to avoid Israel.

The first breakthrough in Israel’s energy isolation came with the peace treaty with Egypt. Israel purchased oil from Egypt for several years, until the late 1990s when Egyptian oil reserves dwindled, leading Egypt to announce it could no longer supply Israel with oil (Koren, 1996). Another breakthrough occurred in 2000 when gas pipelines were laid between Israel and Egypt. Israel bought gas from Egypt for several years, aiming to strengthen economic ties between the two countries and warm the cold peace between them (Bahgat, 2008). However, this gas alliance was repeatedly tested and nearly collapsed following a series of terrorist attacks on the pipeline in Sinai by global jihad organizations, which gained a foothold in Sinai after the Arab Spring events in 2011 (Even, 2012; Tuitel, 2014).

Eastern Mediterranean Alliances Before October 7, 2023

The natural gas discoveries off Israel’s shores have significantly affected the relationships discussed above. Beginning in 2019, the direction of the gas flow in the pipelines changed, as Israel started selling gas to both Egypt and Jordan, with the intent of improving its diplomatic relations with these countries. Having signed a gas supply agreement with Jordan in 2016, it is now believed that Israel provides the majority of Jordan’s gas (Elmas, 2023b). Egypt, on the other hand, purchases Israeli gas to meet its growing domestic energy needs and also to liquefy it for sale to European markets at a higher price. This has become a significant industry in the Egyptian economy.

In cooperation with Egypt, Israel established the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), which forms an energy alliance between Israel, Egypt, Cyprus, Jordan, Greece, Italy, and the Palestinian Authority (Wolfrum, 2019; Mitchell, 2021b). Egypt has been exerting pressure recently to increase the flow of gas due to its aspirations of becoming a regional processing and export center, as well as its substantial reliance on this industry. In May 2023, the construction of another gas pipeline that will pass through the Nitzana Border Crossing between Egypt and Israel was announced (Elmas, 2023a). These agreements and alliances have laid the groundwork for significant infrastructure that will facilitate further agreements aimed at making Israel an energy exporter (though not a major player in the market) and a transit country for East-to-West energy corridors. Some critics argue that these energy agreements between Israel and its neighboring countries pose a threat to the Palestinian issue, as it reduces the willingness of these neighboring countries to pressure Israel on this matter (e.g., Baconi, 2017).

Israel’s opponents have a vested interest in undermining its regional energy status. Iran comes into play here as a regional power that financially supports Hamas with hundreds of millions of dollars annually and supplies the majority of its weapons. This connection has been ongoing for many years, although it has had its ups and downs. Hamas can therefore be seen as an Iranian proxy, serving Iran’s aggressive objectives in its conflict with Israel. Iran leads the “resistance axis” or “camp” of proxy countries and organizations in the region, including Hezbollah in Lebanon and Syria, militias in Iraq, and the Houthis in Yemen (Shine & Catran, 2018; Seliktar & Rezaei, 2020).While Iran and Hamas share an extreme Muslim religious ideology, it is worth noting that Iran is a Shiite country supporting a Sunni organization, both of which are two ethnic-religious groups engaged in all-out warfare against one another in other parts of the Muslim world. On the other side, the moderate Sunni camp is led by Saudi Arabia and includes countries like Bahrain, the UAE, Jordan, and Egypt (Seliktar & Rezaei, 2020; Karsh, 2023; Dunning & Iqtait, 2023).

Among the financial backers of Hamas, Qatar stands out as a unique player. Although it is theoretically aligned with the Sunni camp, Qatar has always avoided fully aligning and cooperating with Saudi Arabia. Instead, it has adopted a hedging strategy by engaging with players from all sides. Qatar’s surprisingly friendly relations with Iran, despite being at odds with its neighbors, are particularly noteworthy. One of the main reasons for this attitude is the energy question. Both countries share South Pars, one of the largest gas fields in the world. As the second largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) globally, Qatar produces significantly more from the shared field than Iran does, depleting its own reserves in the process. Concerns about potential disputes over energy production and transportation in the Persian Gulf have pushed Qatar to align itself with Iran to the best of its abilities in the geopolitical arena (Kamrava, 2017). However, Qatar’s support for Hamas, combined with these actions, has resulted in its growing distance from the Sunni camp, and its affiliation is now unclear (Chaziza, 2020a).

One of the fundamental elements of the conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia is their shared threat to the movement of oil and gas tankers in the Strait of Hormuz, the gateway to the Persian Gulf, which affects oil and gas consumers worldwide. Saudi Arabia is particularly concerned about the increasing strength of proxy organizations in the Bab al-Mandab Strait, which leads to the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, as well as the presence of rogue organizations like the Islamic State cells in Sinai. These areas have experienced repeated attacks on energy infrastructure and tankers, destabilizing global energy supply and economic stability. This common interest in maintaining economic stability aligns the Saudi-led moderate Sunni camp with the US and its Western allies. These countries are committed to supporting Saudi Arabia strategically and preventing energy crises. This is especially important considering the rising global inflation, which is sensitive to energy price increases (Rodrigue, 2004; Pascual & Zambetakis, 2010; Seliktar & Rezaei, 2020).

If the sea route for oil, gas, hydrogen, and other goods is threatened, using Israel as a land energy corridor from the UAE and Saudi Arabia could be a possible alternative. It would involve laying pipelines through a more secure route to reach Europe via the Mediterranean Sea, which is in Saudi Arabia’s interest. In contrast, Iran views this prospect as a weakening of its strategic leverage over the choke point it currently controls, posing a threat to its Saudi adversary. The process of establishing this corridor began with the signing of the Abraham Accords in 2020, through which Israel and the UAE agreed to transport oil through the Eilat–Ashkelon oil pipeline and utilize the storage facilities located alongside it. Crude oil from the Persian Gulf is intended to be shipped to Eilat or transported through pipelines to the city of Yanbu on the Red Sea coast of Saudi Arabia, then northward to Eilat, and finally to the Ashdod Port (Barkat, 2020). It is noteworthy that following the signing of the Abraham Accords, Hamas initiated a missile attack during the 2021 round of fighting (Operation Guardian of the Walls), damaging a large oil storage tank in Ashkelon and setting it ablaze. This round of fighting also led to the closure of Israel’s southern gas wells, demonstrating the capability of the Gaza Strip to threaten Israel’s energy assets and the Saudi Arabian axis (Levi, 2021).

Important talks to expand the corridor that passes through the Saudi Arabian–Israeli area and extend it westward or eastward have persisted. In the months leading up to October 2023, several large-scale infrastructure projects were approved one after another:

- The first is construction of a pipeline connecting Israel’s gas fields to a Cypriot liquefaction facility that will market the liquefied gas to Greece, and from there to Europe (Keller-Lynn, 2023). This is part of the ambitious EastMed pipeline project, the planning of which began a decade ago. It is designed to connect Israel’s gas reservoirs to Greece and Europe, but its economic and technical viability has not yet been demonstrated. If implemented, the project will become the world’s longest undersea pipeline (Krasna, 2023).

- The second is the EuroAsia Interconnector undersea power line, which will connect the electrical grids of Israel, Cyprus, and Greece. This project will make it possible to stabilize the supply of electricity between the countries and will enable one of those countries to take advantage of electrical surpluses generated by another (Mitchell, 2021a; Kahana, 2023).

- The third and most important is a railway line, with potential for laying energy cables and pipelines alongside it, connecting Europe to Jordan, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and India via the Haifa Port and Beit Shean. This will be under the umbrella of the US, which is mediating and matchmaking between the various parties along the corridor and promising its guarantee for the main requirement needed in order to connect the parts of the puzzle—a normalization agreement between Israel and Saudi Arabia (Kapoor, 2023).

- The fourth is a new gas pipeline from Israel to Egypt that will expand the latter’s ability to liquefy and export gas to Europe (Elmas, 2023a; Elmas 2023d), plus the laying of a gas pipeline between Egypt and Saudi Arabia through the Strait of Tiran, for the sale of Egyptian and Israeli gas to Saudi Arabia. Despite the fact that Saudi Arabia has huge gas reserves, it has yet to establish the export of its gas and uses a great deal of gas for internal consumption (Zaken, 2023).

- The fifth is the construction of a hydrogen pipeline that will flow to Europe from a futuristic infrastructure project from the Saudi Arabian city of Neom on the Red Sea coast, and also from planned fields in India through pipelines to be laid alongside the railway line from Saudi Arabia to the Haifa Port (Martin, 2023).

The US and the constellation that it leads have many inherent interests in Israel and Saudi Arabia, both together and separate, but one strong interest stands out above all others—the struggle against the emerging “Asian constellation.” The start of this struggle is the freeing of the EU from the Russian energy bear hug, as will be explained below.

Figure 1: Energy Corridors in the Middle East

The Bearhug

As mentioned earlier, Russia has emerged as an energy superpower in recent decades, possessing vast reserves of oil and natural gas, and has strategically utilized them to enhance its geopolitical standing. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and under Vladimir Putin’s long rule, Russia has been striving to regain its position of international influence As part of this endeavor, Russia has renewed its interest in the Middle East. One of its goals is to establish alliances with various Muslim countries or present itself as their partner. By doing so, Russia can neutralize pressure from these countries, as a result of its conflicts with Muslim minorities in southern Russia. Russia’s collaboration with Iran to support the Assad regime in Syria has solidified their budding alliance and essentially has turned Syria into a joint protectorate. Moreover, despite their cultural, religious, and ideological differences, Russia and Iran have found common ground in their opposition to the West and American hegemony (Dannreuther, 2012; Lasensky & Michlin-Shapir, 2019; Cafiero, 2020). They also share similar values with China, as described below. In this context, Russia and Iran are deepening their economic and military cooperation (Grise & Evans, 2023; Phillips & Brookes, 2023). This has become evident through the Russians’ use of Iranian drones in the attack on Ukraine and, more recently, with the sale of advanced Russian Sukhoi 35 warplanes to Iran after October 7 (Bar, 2023).

The Russian aggression against Ukraine began a decade ago when Russia started annexing parts of Ukraine’s territory through force, culminating in a brutal all-out offensive in 2022. Russia provided various justifications for this war, some of which were clearly fictitious. These included claims that the territory historically belonged to the Czarist Empire and that the Ukrainian regime needed “de-Nazification.” The primary reason given was that Russia aimed to push away the perceived Western threat from its borders, particularly in light of discussions regarding Ukraine’s potential entry into the NATO defensive alliance.

Many have criticized the US and Western countries, blaming them for provoking the war. While it is important to consider this argument, we should also explore other explanations that may receive less attention in discussions and research. First, examining the chronology of events clearly shows that Ukraine was initially hesitant about cooperating with NATO until 2014. It was the Russian attacks that ultimately pushed Ukraine into the arms of the West. Second, it is worth noting that Russia did not respond in the same manner when neighboring countries like Poland, Hungary, and the Baltic states joined NATO.

To better understand Russia’s fundamental motive in the conflict, Johannesson and Clowes (2022) suggest examining the production and consumption aspects of the energy issue. Russia specifically targeted and annexed parts of Ukraine that happen to contain the richest gas and coal deposits. Ukraine had hoped to reduce its dependence on Russian gas and become a gas exporter to Europe, which posed a significant challenge to Russia. These territories also house heavy industries that heavily rely on Russian gas.

Moreover, it is important to recognize that 19% of the Russian gas exported to Europe passes through Ukraine, with transit costs exceeding $1 billion in 2017. In essence, the Russian invasion aims to gain control over these deposits, maintain Russian control of gas supply to major Ukrainian consumers, and secure control over gas corridors passing through Ukraine. This strategic move allows Russia to hinder competition that would reduce Europe’s reliance on Russian energy (Johannesson & Clowes, 2022).

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine surprised the Russians with the strong support from the West. The US, concerned about the increasing aggression of its rival, not only provided arms to Ukraine but also imposed economic sanctions on Russia. President Biden needed the cooperation of the EU economies for this purpose but was hindered by Russia’s energy strategy. Russia had taken steps to ensure Europe’s heavy dependence on Russian gas (Schattenberg, 2022; Driedger, 2022). While most EU countries cooperated with the sanctions, some found it challenging to apply them to the gas sector, including Germany, Belgium, Spain, France, and others. These countries continued to consume significant quantities of Russian gas (Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, 2023).

Upon realizing the extent of the Russian threat, the EU focused on developing and implementing the REPowerEU plan to diversify its gas suppliers. They also worked vigorously on building infrastructure to connect with gas fields in North Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, and potential gas and hydrogen pipelines from Saudi Arabia and Israel (European Commission, 2022). As a result of the Russian oil sanctions, European demand for new oil suppliers has increased. Russia has been offering discounted oil to East Asia to compete in a market traditionally dominated by Saudi Arabia and the UAE. These countries are now seeking alternative routes to bypass the Bab al-Mandab Strait and meet the new European demand. While the use of the Eilat–Ashkelon oil pipeline is being considered, it is likely to cause potential environmental damage to the Eilat Port (Rettig, 2023), making an oil pipeline along the railway line from Riyadh to Haifa Port a possible consideration in the future. Europe’s success in establishing connections with alternative energy suppliers through Israel has become a key American interest, as it is the only way to help Europe break free from Russia’s grip and exert maximum pressure on Russia.

The New Silk Road

All of the events described so far have taken place in the shadow of the titanic struggle in the global theater between the US and China (Heiduk, 2022). For a long time, Israel has seen potential in closer ties with China. This aspiration was motivated by a risk-hedging strategy in which Israel searched for support, instead of relying exclusively on an alliance with the US, especially when concerns arose due to strained during the Obama administration (Chaziza, 2018). In addition to intensive trade, Israeli–Chinese relations have featured joint investments, academic and technological collaborations, imports of Chinese personnel, and the opening of large infrastructure tenders to Chinese companies. One of the prominent projects being carried out by Chinese firms is the construction of the Haifa Bay Port, which the US perceives as a strategic threat to its dominance in the region (Chaziza, 2018). By opening its markets and strengthening its relations with China, Israel had expected to become a station along the Belt and Road Initiative—China’s well-known infrastructure project announced in 2013, on which it has been working ever since. This initiative involves what is known as the “New Silk Road,” considered the largest infrastructure connection project in human history, connecting China to Europe through two land routes and one sea route. It entails the construction of an extensive network of transportation infrastructure, including energy supply lines from the rich reserves of Central Asia. These routes will reach China and, with Chinese sponsorship and investment, also Europe. This ambitious endeavor serves multiple purposes and promotes economic development wherever it goes. However, two overarching strategic goals stand out: The land axes will reduce China’s dependence on trade and energy passing through the choke point of the Strait of Malacca and will help China consolidate its influence throughout the Eurasian continent by forging economic alliances with many countries (Hao et al., 2020; Garlick & Havlova, 2021; Soboleva & Krivokhizh, 2021; Gresh, 2023).

It is now evident that Israel’s efforts to participate in the Belt and Road Initiative are not as successful as those of the larger countries in Central Asia. China has singled out Iran and Russia as more important countries due to their geographic location, the energy they have promised to supply to China (especially given the Western sanctions on trade with these two countries), and their general willingness to align with China in opposition to American hegemony (Lavi et al., 2015; Yeniacun, 2021; Gresh, 2023). Qatar, one of the main suppliers of natural gas to China (which recently became the world’s largest gas consumer), has also been identified as a strategic target. Within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative, China–Qatar relations have developed through investments, infrastructure projects, and military cooperation. Qatar views this as an essential risk mitigation strategy amid the crisis in its relations with its Persian Gulf neighbors and the Sunni camp (Chaziza, 2020a).

China had also identified other countries in the Persian Gulf, including Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, as targets for investment. Initially, these countries agreed to this as a way to hedge against risk because the US, their defense ally, showed signs of strain following its failure in Iraq and its decreasing involvement in the Middle East (Chaziza, 2020b; Afterman, 2021; Liao, 2023). As part of this warming of relations, China attempted to mediate between Saudi Arabia and Iran. The West’s alarm over China’s increasing presence in the region came rather late, and now the US is pressuring Saudi Arabia to end its rapprochement with China and align with America instead (Liao, 2023).

To highlight the benefits of choosing the West, the US has launched a competing project to the Belt and Road Initiative called the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor. This corridor includes sea routes, railways, and pipelines for gas, oil, and hydrogen. It began with the Abraham Accords and has expanded to include intercontinental communication cable projects, such as Google’s Blue-Raman cable, which will pass through Israel instead of Egypt’s extensive communication network (Ziv, 2020). The project will culminate with the anticipated normalization agreements between Israel and Saudi Arabia, which will involve the construction of railways, gas pipelines, hydrogen pipelines, and oil pipelines. These projects were announced in the months preceding the Hamas attack, including in September shortly before the attack (Martin, 2023).

Figure 2: Energy Corridors in Asia and Europe

The New Great Game

The geopolitical significance of the Asian region on the global stage is increasing. According to Campos and Fernandes (2017), “currently, Central Asia, as part of the Heartland, has been going through the so-called ‘New Big Game,’ characterized by rivalry and competition between the United States, the United Kingdom, and other NATO countries, against Russia, China, and other States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization on the other,” a competition that will allow the victor to control the pipelines, energy routes, and supply contracts (p. 26). The term “New Big Game” or “New Great Game” originated from the struggle between the Russian Empire and the British Empire for control over Central Asia in the 19th century (Chen & Fazila, 2018).

In the current game taking place in a vast region stretching from China to Eastern Europe, including Central and Southern Asia and the Middle East, the responses of countries in the international arena to the Hamas attack and the war in the Gaza Strip largely reflect their interest in energy geopolitics. It was predictable that Muslim countries in the Iranian Shiite camp would have a hostile attitude, but Russia and China’s condemnation of Israel surprised many (Einav, 2023; Qi, 2023). A key factor to consider is the existence of a complex alliance among these countries, which can be referred to as “the Asian constellation.” They have identified common interests in joint infrastructure projects, military cooperation, and, most importantly, the need to maintain control over energy corridors. This includes controlling their own energy corridors while posing a threat to the corridors of rival countries. For instance, instead of aligning with other countries in the Sunni camp, Qatar—a major supporter of Hamas—is increasingly forming partnerships with Iran and China due to shared economic interests, particularly in the energy sector (Kamrava, 2017; Chaziza, 2020a).

The same theoretical explanation reveals why the Sunni camp, led by Saudi Arabia, is maintaining a restrained stance toward Israel. Although the Arab public has a strong emotional hostility toward Israel, at the same time, if Saudi Arabia were to turn its back on Israel, it would lose out on an important infrastructure project. Additionally, it could lose support from the US, including the potential to develop a nuclear program and to continue to receive defense protection. Moreover, Saudi Arabia would face an increasing threat from its Iranian enemies. This explanation also helps us understand why President Biden strongly supports Israel. By establishing Israel as an energy corridor under American sponsorship, Biden’s efforts to counter Russia and China’s influence in Asia will receive a significant boost. This corridor is a key supplementary endeavor to the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy” that the US has been promoting recently. The strategy aims to create a coalition in southern Asia, from the Philippines to India and the Horn of Africa, in order to counter China’s growing power in Central and Northern Asia (Heiduk, 2022).

The US, together with its partner Saudi Arabia, must address multiple challenges at various choke points. This includes dealing with the active corridor in the Red Sea, attacks by the Houthis in the Bab al-Mandab Strait, threats from Hamas to the infrastructure area between Eilat and Ashkelon, and the Hezbollah threat to the planned route between Saudi Arabia and Haifa. These challenges are further fueled by political threats orchestrated by organizations that incite global public opinion against Israel. This incitement hampers the normalization process with Saudi Arabia, which is crucial for the construction of alternative infrastructure in these areas. This issue is of great importance to the US, as the presence of China in economic and military projects in the Middle East region poses significant challenges. For example, China has constructed a military base in Djibouti overlooking the Bab al-Mandab Strait (Orion, 2016), which further complicates the task of safeguarding shipping in the Red Sea. These challenges cast a shadow over the ability of the US to provide protection and stability in the region between the Pacific Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, which ultimately threatens its position as the dominant power—a grave strategic threat.

In addition, Turkey’s repeated distancing from Israel, despite tensions in its relations with Iran, takes on new significance when considering the presence of important pipelines within its territory. These pipelines serve as an alternative route for both Israel to the south and Ukraine to the north. As part of the Belt and Road Initiative, gas is being transported from Central Asia to Greece and Italy through the existing TANAP and TAP pipelines (Hao et al., 2020; Gersh, 2023). Furthermore, the planned expansion of the TurkStream pipeline from Russia to Turkey is expected to allow Russia to bypass sanctions on their gas, ultimately delivering it to Europe via Turkey (Ellis, 2017; Chyong et al., 2023). Turkey places significant strategic importance on its position as a hub for gas transportation from East to West, particularly for the purpose of exerting pressure on the EU (Elmas, 2023c). Consequently, Turkey is in fierce competition with Greece to become the leading transit country in the region and is deeply concerned about the growing influence of its rival. Turkey is particularly unsettled by Greece’s participation in the EMGF and the energy projects that connect Israel with the Hellenic countries, Cyprus and Greece, effectively bypassing Turkey (Çelikpala, 2021; Krasna, 2023).

In the months leading up to the Hamas attack, Turkey tried to persuade Israel to partner with Greece and transport its gas to Europe through Turkey (Elmas, 2023c). However, after the attack, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan openly sided with Hamas and even threatened Israel, effectively ending any potential energy cooperation between Turkey and Israel. Some interpreted Erdoğan’s actions as a strategic error driven by ideology and internal political interests (Markind, 2023). However, it is also possible that Erdoğan’s actions were a gesture aligning with the Asian constellation and distancing Turkey from American influence. If this is the case, it sheds new light on Turkey’s involvement in the Middle East over the past two decades. Turkey has a long-standing history of supporting Hamas and opposing Israel’s policies toward Gaza, as evidenced by its organizing the Mavi Marmara flotilla and hosting Hamas members in its territory. Additionally, Turkey provides monetary assistance in the Negev area through various charity and aid organizations in support of the Bedouin struggle against the Israeli government over unrecognized villages (Bigman, 2013; Dekel et al., 2019). By extending Turkish sponsorship to both the Gaza Strip and the Negev, Turkey enhances its ability to pose a threat to the entire land bridge. It is important to note that the supply of oil to Israel from Central Asia passes through Turkey. Despite the hostile rhetoric, Turkish gas shipments to Israel were not halted following the Hamas attack (bne IntelliNews, 2023). Nevertheless, this additional choke point serves as a means for Turkey to exert pressure on Israel.

Egypt’s ambivalent stance toward the conflict in Gaza also becomes clear. Egypt has a dislike for Israel and is dissatisfied with the development of energy and communication routes that will compete with Egypt’s control over the Suez Canal and the Sumed pipeline, which are crucial elements in Egypt’s struggling economy. At the same time, Egypt is a member of the Saudi Arabian–Sunni alliance and receives protection and support from the US. Due to increasing Iranian threats along the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, Egypt feels compelled to maintain this military protection. Additionally, there are various Islamic jihad organizations gaining strength in Sinai, which pose a threat to the gas projects passing through the area. Cooperation with Israel in combating these organizations, which even includes Israeli attacks within Egyptian territory, holds great importance (Ynet, 2018). Furthermore, Egypt’s economic and energy ties with Israel have become increasingly significant over time. As Egypt has transitioned from being a natural gas exporter to an importer, it has become crucially dependent on Israeli gas (Krasna, 2023). This dependence serves as a counterweight. Despite ideological differences between Egypt and Hamas, this factor likely discourages Egypt from providing strong support to the latter. Jordan also expresses strong criticism toward Israel, particularly due to its large Palestinian population. However, Jordan’s reliance on Israeli gas in recent years limits its ability to take concrete measures to express this disapproval. This is partly because the new Chinese-built power station in Jordan, which is based on shale oil, supplies energy at a much higher price compared to Israeli gas (Elmas, 2023b).

Finally, let us examine the perspectives of different European countries on the conflict and how they align with their energy-political interests. Ukraine’s support for Israel is clear and understandable. This is due to the realization that Russia, Ukraine’s adversary, is aligned with countries hostile to Israel, even though this hostility is not openly declared, unlike the tension between Israel and Iran. Germany, too, has multiple political and ideological reasons for supporting Israel. It is worth noting that Germany faces a significant threat from Russia and is actively seeking a gas solution through the IMEC corridor, as mentioned earlier. Greece shares similar motivations for its support of Israel (Tzogopoulus, 2023). In recent years, Greece has been viewed as a crucial strategic partner for American investment in the region, serving as an alternative to Turkey. Turkey’s distancing from the West, coupled with its threatening rhetoric toward Greece, has led to a growing rift between Turkey and both Greece and the US. As a response, the US is positioning Greece as an energy transportation hub and a NATO military control point for the entire Eastern Mediterranean, as well as a gateway to Bulgaria and the rest of Eastern Europe. Consequently, both Greece and the US prioritize the development of infrastructure connecting Greece with Cyprus and Israel (Ellis, 2017).

In contrast, some European countries are pursuing different policies toward Israel, ranging from neutrality to condemnation. While this cannot be directly attributed to the energy question, energy can be seen as a factor that enables them to take such a stance. Several countries, particularly those governed by leftist political parties, have a clear political interest in criticizing Israel due to their principled stand on the Palestinian issue. Additionally, they may aim to appease the Muslim immigrant communities within their countries. This political alliance, often referred to as “the red-green alliance” (Karagiannis & McCauley, 2013), allows these countries to express their criticism more openly. It is essential to consider that countries with less reliance on the US or those that believe they are less dependent on it have more freedom to express their views. In light of this, it is worth noting that Belgium and Spain, both significant purchasers of Russian gas, are unwilling to cooperate with American sanctions against Russia. They also continue to expand their gas supply from North African countries. This could partially explain why the leaders of these countries were able to visit the Gaza Strip border as a symbolic gesture during a prisoner exchange in the war, expressing solidarity with the Palestinians (Yosef, 2023). As mentioned earlier, it seems that the energy interest does not solely determine the stance of European countries toward Israel. However, when there is no significant energy or geopolitical dependence on the camp that supports Israel, political leaders are likely to exploit this situation for their own needs.

Conclusion

To return to the question we initially posed—what is shaping the global attitude toward Israel in its struggle against Hamas—we can now offer a substantial answer amid the complex considerations of each country. The “New Great Game” borders took form on October 7, 2023, specifically along the Gaza Strip, signifying the emergence of a second Cold War centered on Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East. This multifaceted conflict is gradually escalating, with hot fronts developing in Ukraine, Israel, Yemen, and involving Saudi Arabia and Iran. It is important to note that while the powers involved did not directly intervene in the October 7 attack, their shared interests—backed by trillions of dollars and control of strategic assets—significantly influence the countries’ attitudes toward Hamas.

We must strive to decipher the rhetoric of world leaders, as support for Hamas—whether economic, military, technological, or political—is driven by their concrete material interests, and this motivation will persist in the future. Hamas would not have obtained its tunnels, weapons, intelligence capabilities, electronic warfare, and global media campaign without assistance. These resources were provided to Hamas as part of an agreement, where Hamas fulfills its mission in exchange. Consequently, Hamas has become a “choke point” for intercontinental energy corridors. This is evident in their attempts to damage infrastructure, such as the 2021 attack on the fuel tank in Ashkelon, as well as their ability to hinder alliances and agreements for energy transportation through Israeli territory. While these efforts have not yet succeeded, as the agreements with Saudi Arabia may still be implemented in the future, preventing the development of energy infrastructure holds strategic importance for numerous global players, whether they initially supported Hamas or are now benefiting from its actions.

Contrary to theories such as “the clash of civilizations,” this is not a conflict between great cultures at war with each other, such as Islam versus the West. Nor is it a conflict between values or political philosophies, such as democratic countries versus dictatorships. The constellations connecting countries or axes of countries and organizations encompass a mixture of all these factors. On one side, there is a “Western constellation” that combines the democratic West with autocratic Muslim countries in the Sunni camp, as well as India and Israel. On the other side, there is an “Asian constellation” led by China and consisting of Russia, Shiite Muslim countries, Sunni countries such as Qatar and organizations such as Hamas, as well as Western countries or political parties on the left side of the political spectrum. While ideology and culture play important roles in motivating various players to act, we must not overlook the significant economic and geopolitical factors that underlie these actions. This includes the extensive infrastructure of alliances centered around resources and control, as well as military and commercial partnerships, particularly in the realm of energy resources and energy corridors.

References

Afterman, G. (2021, January). China’s evolving approach to the Middle East: A decade of change. Strategic Assessment, 24(1), 154–160. https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Adkan24.1Eng_6-12.pdf

Asia, I. (1994). Focus of the conflict: The struggle for the Negev 1947–1956. Yad Ben Zvi. (In Hebrew).

Bahgat, G. (2008). Energy and the Arab-Israeli conflict. Middle Eastern Studies, 44(6), 937–944. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263200802426195

Baconi, T. (2017, March 12). How Israel uses gas to enforce Palestinian dependency and promote normalization. Al-Shabaka. https://al-shabaka.org/briefs/israel-uses-gas-enforce-palestinian-dependency-promote-normalization/

Bar, N. (2023, November 28). Russia approves sale of advanced warplanes, helicopters to Iran. Israel Hayom. (In Hebrew). https://www.israelhayom.co.il/news/world-news/middle-east/article/14877841

Barkat, A. (2020, September 16). Israel to propose Saudi – Israel oil pipeline. Globes. https://en.globes.co.il/en/article-israel-to-propose-saudi-israel-oil-pipeline-1001343034

Bigman, A. (2013, July 10). Turkish money and the illegal Negev. Mida. (In Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/34d47beu

bne IntelliNews. (2023, October 30). Oil continues to flow to Israel via Turkey despite Erdogan’s vehement speeches on plight of Gaza. https://www.intellinews.com/oil-continues-to-flow-to-israel-via-turkey-despite-erdogan-s-vehement-speeches-on-plight-of-gaza-299108/

Cafiero, G. (2020, April 2). What do Russia and Hamas see in each other? Middle East Institute. https://www.mei.edu/publications/what-do-russia-and-hamas-see-each-other

Campos, A., & Fernandes, C. P. (2017). The geopolitics of energy. In C. P Fernandes & T. F. Rodrigues, (Eds.) The geopolitics of energy and energy security (pp. 23–40). Instituto da Defesa Nacional. https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/41897/1/cf_ac_tfr_geopoliticsofenergy_2017.pdf

Çelikpala, M. (2021). Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean: Between energy and geopolitics. In V. Talbot & V. Magri. (Eds.) The scramble for the Eastern Mediterranean (pp. 46-28). Ledizioni LediPublishing.

Chaziza, M. (2018). Israel-China relations enter a new stage: Limited strategic hedging. Contemporary Review of the Middle East, 5(1), 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347798917744293

Chaziza, M. (2020a). China-Qatar strategic partnership and the realization of One Belt, One Road Initiative. China Report, 56(1), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009445519895612

Chaziza, M. (2020b, October 4). China-Bahrain relations in the age of the Belt and Road Initiative. Strategic Assessment, Research Forum, 23. https://www.inss.org.il/strategic_assessment/china-bahrain-relations-in-the-age-of-the-belt-and-road-initiative/

Chen, X., & Fazilov, F. (2018, June 19). Re-centering Central Asia: China’s “New Great Game” in the old Eurasian heartland. Palgrave Communications, 4(71). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0125-5

Chyong, K., Corbeau, A. S., Joseph, I., & Mitrova, T. (2023, January 19). Future options for Russian gas exports. Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia | SIPA. https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/publications/future-options-russian-gas-exports/

Dannreuther, R. (2012, April 2). Russia and the Middle East: A Cold War paradigm? Europe-Asia Studies, 64(3), 543–560. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09668136.2012.661922

Dekel, T., Meir, A., & Alfasi, N. (2019). Formalizing infrastructures, civic networks, and production of space: Bedouin informal settlements in Be’er-Sheva Metropolis. Land Use Policy, 81, 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.09.041

Driedger, J. J. (2022). Did Germany contribute to deterrence failure against Russia in early 2022? Central European Journal of International and Security Studies, 16(3), 152–171. https://www.cejiss.org/images/docs/Issue_16-3/Drieger_-_16-3_web.pdf

Dunning, T. and Iqtait, A. (2023). Arming Palestine: Resistance, evolution, and institutionalisation. In A. Vysotskaya, G. Vieira, & M. Eslami (Eds.), The arms race in the Middle East: Contemporary security dynamics (pp. 171–193). Springer International Publishing.

Ellis, T. (2017, September 19). Greece ‘A pillar of U.S. strategy in the region.’ Interview with US Ambassador to Greece Geoffrey R. Pyatt. U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Greece. https://gr.usembassy.gov/greece-pillar-us-strategy-region/

Elmas, D. S. (2023a, May 8). Cabinet approves expansion of Israel-Egypt gas pipeline. Globes. https://en.globes.co.il/en/article-cabinet-approves-expansion-of-israel-egypt-gas-pipeline-1001445859

Elmas, D. S. (2023b, July 13). China’s power play pins down Jordan. Globes. https://en.globes.co.il/en/article-chinas-power-play-pins-down-Jordan-1001452225

Elmas, D. S. (2023c, July 16). Erdogan’s plan for controlling gas prices in Europe. Globes. (In Hebrew). https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001452443

Elmas, D. S. (2023d, July 27). Egypt pressing Israel to increase natural gas exports. Globes. https://en.globes.co.il/en/article-egypt-pressing-israel-to-increase-gas-exports-1001453486

European Commission. (2022, May 18). REPowerEU Plan. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2022%3A230%3AFIN&qid=1653033742483

Even, S. (2012, May 6). Egypt’s revocation of the natural gas agreement with Israel: Strategic implications. INSS Insight, No. 332. https://www.inss.org.il/publication/egypts-revocation-of-the-natural-gas-agreement-with-israel-strategic-implications/

Feldman, B. C. D., & Mil-Man, A. (2023, December 18). Russia’s ‘new world order’ and the Israel-Hamas war. INSS Insight, No. 1801. https://www.inss.org.il/publication/russia-swords-of-iron/

Garlick, J., & Havlova, R. (2020, September 20). The dragon dithers: Assessing the cautious implementation of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Iran. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 62(4), 454–480. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15387216.2020.1822197

Gazit, S. (2014, July 30). What motivates Hamas? Israel Defense. (In Hebrew). http://tinyurl.com/494dsmcc

Gresh, G. F. (2023). China's Maritime Silk Route and the MENA region. In Y. H. Zoubir (Ed.), Routledge Companion to China and the Middle East and North Africa. Routledge.

Grise, M., & Evans, A. T. (2023, October). The drivers of and outlook for Russian-Iranian cooperation. Rand Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PEA2800/PEA2829-1/RAND_PEA2829-1.pdf

Hao, W., Shah, S. M. A., Nawaz, A., Asad, A., Iqbal, S., Zahoor, H., & Maqsoom, A. (2020, October 12). The impact of energy cooperation and the role of the One Belt and Road Initiative in revolutionizing the geopolitics of energy among regional economic powers: An analysis of infrastructure development and project management. Complexity, 2020, Article ID 8820021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8820021

Heiduk, F. (2022). Asian geopolitics and the US-China rivalry. Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. (2023, October 31). Europe’s LNG capacity buildout outpaces demand. https://ieefa.org/articles/europes-lng-capacity-buildout-outpaces-demand

Johannesson, J., & Clowes, D. (2022, February). Energy resources and markets – Perspectives on the Russia–Ukraine war. European Review, 30(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798720001040

Kahana, A. (2023, July 3). History: On the way to electric cable connecting Israel to Europe. Israel Hayom. (In Hebrew). https://www.israelhayom.co.il/news/local/article/14348808

Kamrava, M. (2017). Iran-Qatar relations. In Bahgat, G., Ehtenshani, A., & Quilliam, N. (Eds.), Security and bilateral issues between Iran and its Arab neighbors (pp. 167–187). Palgrave Macmillan.

Kapoor, S. (2023, September 26). IMEC: The politics behind the new geopolitical corridor that’s shaking up global alliances. The Probe. https://theprobe.in/columns/imec-unveiled-the-u-s-led-counter-to-chinas-bri-thats-shaking-up-global-alliances/

Karagiannis, E., & McCauley, C. (2013, March 6). The emerging red-green alliance: Where political Islam meets the radical left. Terrorism and Political Violence, 25(2), 167–182. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09546553.2012.755815

Karsh, E. (2024, January 9). The Israel-Iran conflict: between Washington and Beijing. Israel Affairs, 29(6), 1075–1093. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13537121.2023.2269694

Keller-Lynn, C. (2023, September 4). PM: Decision on route for exporting natural gas to Europe expected in ‘3-6 months.’ The Times of Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/pm-decision-on-route-for-exporting-natural-gas-to-europe-expected-in-3-6-months/

Koren, O. (1996, December 11). Egypt to sell only 60% of oil commitment to Israel in Camp David Accords. Globes. (In Hebrew). https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=134844

Krasna, J. (2023, September 26). A long, hot summer for Eastern Mediterranean gas politics. Foreign Policy Research Institute, Middle East Program. https://www.fpri.org/article/2023/09/a-long-hot-summer-for-eastern-mediterranean-gas-politics/

Lasensky, S. B., & Michlin-Shapir, V. (2019, October). Avoiding zero-sum: Israel and Russia in an evolving Middle East. In K. Mezran & G. Massolo (Eds.), The MENA region: A great power competition (pp. 141–157). Ledizioni LediPublishing. https://www.ispionline.it/sites/default/files/pubblicazioni/ispi_report_mena_region_2019.pdf

Lavi, G., He, J., & Eran, O. (2015, October). China and Israel: On the same Belt and Road? Strategic Assessment, 18(3), 81–90. https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/systemfiles/adkan18_3ENG%20(4)_Lavi,%20He,%20Eran.pdf

Levi, H. J. (2021, May 11). Trans-Israel Pipeline Oil Container in Flames. Jewish Press. https://www.jewishpress.com/news/business-economy/trans-israel-pipeline-oil-container-in-flames-after-hit-by-gaza-rocket/2021/05/11/

Liao, J. X. (2023, October 29). Antisemitic comments increase across Chinese social media. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/world/china/antisemitic-comments-increase-across-chinese-social-media-6e73cf5c

Månsson, A. (2014, December). Energy, conflict and war: Towards a conceptual framework. Energy Research & Social Science, 4, 106–116. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214629614001170

Markind, D. (2023, November 1). Another Mideast casualty – Turkey/Israel joint gas exploration. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/danielmarkind/2023/11/01/another-mideast-casualtyturkeyisrael-joint-gas-exploration/?sh=2536fbb15cc3

Martin, P. (2023, September 12). US and EU eye hydrogen exports from India to Europe via Middle East pipeline. Hydrogen Insight. https://www.hydrogeninsight.com/policy/us-and-eu-eye-hydrogen-exports-from-india-to-europe-via-middle-east-pipeline/2-1-1515976

Masuda, T. (2007, December). Security of energy supply and the geopolitics of oil and gas pipelines. European Review of Energy Markets, 2(2), 1–32. https://eeinstitute.org/european-review-of-energy-market/EREM%205_Article%20Tatsuo%20Masuda.pdf

Milina, V. (2007). Energy security and geopolitics. Connections: The Quarterly Journal, 6(4), 25–45. http://connections-qj.org/article/energy-security-and-geopolitics

Mitchell, G. (2021, February). Supercharged: The EuroAsia interconnector and Israel’s pursuit of energy interdependence. Mitvim. https://mitvim.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Gabriel-Mitchell-The-EuroAsia-Interconnector-and-Israels-Pursuit-of-Energy-Interdependence-February-2021.pdf

Mitchell, G. (2021b). Israel’s quest for regional belonging in the Eastern Mediterranean. In V. Talbot and V. Magri. (Eds), The scramble for the Eastern Mediterranean (pp. 13–28). Ledizioni LediPublishing.

Orion, A. (2016, February 1). The dragon’s tail at the Horn of Africa: A Chinese military logistics facility in Djibouti. INSS Insight, No. 791. https://www.inss.org.il/publication/the-dragons-tail-at-the-horn-of-africa-a-chinese-military-logistics-facility-in-djibouti/

Pascual, C., & Zambetakis, E. (Eds.). (2010). The geopolitics of energy. In Energy security: economics, politics, strategies, and implications (pp. 9–35). Brookings Institute.

Phillips, J., & Brookes, P. (2023, April 27). Undermining joint Russian–Iranian efforts to threaten U.S. interests. The Heritage Foundation. https://www.heritage.org/global-politics/report/undermining-joint-russian-iranian-efforts-threaten-us-interests

Qi, L. (2023, October 29). Antisemitic comments increase across Chinese social media. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/world/china/antisemitic-comments-increase-across-chinese-social-media-6e73cf5c

Rettig, E. (2023, March 12). Israel’s energy market and the war in Ukraine. Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 2, 186. https://besacenter.org/israels-energy-market-and-the-war-in-ukraine/

Rodrigue, J.-P. (2004). Straits, passages and chokepoints: A maritime geostrategy of petroleum distribution. Cahiers de Géographie du Québec, 48(135), 357–374. https://doi.org/10.7202/011797ar

Schattenberg, S. (2022). Pipeline construction as “soft power” in foreign policy: Why the Soviet Union started to sell gas to West Germany, 1966–1970. Journal of Modern European History, 20(4), 554–573. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/16118944221130222

Seliktar, O., & Rezaei, F. (2020). Iran, revolution, and proxy wars. Palgrave Macmillan.

Soboleva, E., & Krivokhizh, S. (2021, May 18). Chinese initiatives in Central Asia: Claim for regional leadership? Eurasian Geography and Economics, 62(5–6), 634–658. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15387216.2021.1929369

Tuitel, R. (2014). The future of the Sinai Peninsula. Connections: The Quarterly Journal, 13(2), 79–92. https://connections-qj.org/article/future-sinai-peninsula

Tzogopoulos, G. N. (2023, December 26). Greece and the Israel-Hamas war. BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 2247. https://besacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/2247-Tzogopoulos-Greece-and-the-Israel-Hamas-War-1.pdf

Wolfrum, S. (2019, November). Israel’s contradictory gas export policy – The promotion of a transcontinental pipeline contradicts the declared goal of regional cooperation. SWP Comment, No. 43. DOI:10.18449/2019C43

Yeniacun, S. H. (2020). Israel’s challenge of stability in the context of BRI’s East Mediterranean policies. İsrailiyat, 7, 75–89. http://tinyurl.com/3mrd6hvd

Ynet. (2018, February 3). Against ISIS: “Israel attacked more than 100 times in Egypt within two years.” (In Hebrew). https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5081824,00.html

Yosef, I. (2023, November 24). Rafah Border Crossing: Spanish, Belgian Prime Ministers demand permanent ceasefire from Israel. News1 First Class. (In Hebrew). https://www.news1.co.il/Archive/001-D-478010-00.html

Zaken, D. (2023, January 27). Surprising change in Jordanian king’s attitude, another development between Israel and Saudi Arabia. Globes. (In Hebrew). https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001436600

Ziv, A. (2020, April 14). Israel to play key role in giant Google fiber optic cable project. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/business/2020-04-14/ty-article/.premium/israel-to-play-key-role-in-giant-google-fiber-optic-cable-project/0000017f-e5ec-da9b-a1ff-edef50650000