Strategic Assessment

Like elsewhere throughout the world, Israel has experienced waves of internal and external migration, and these phenomena have exerted a strong influence on the country’s development, as well as on the phenomenon of acculturation and relations between the majority and minority groups. In the case of Israel, Arab and ultra-Orthodox citizens migrate in an ongoing process into the living spaces of the majority and create mixed spaces. This article examines the influence of these processes of acculturation on social resilience and national security, and explores whether Israel is sufficiently aware of the challenge that these demographic changes create and prepared to address them.

The article surveys acculturation models for absorption of both foreign immigrants and internal migrants from minority groups among the majority group in Western countries, exploring which could be implemented in Israel on a national and municipal level. The assumption is that the rapid growth of minority groups in Israel—including those that do not identify with the national ethos, feel they are outsiders, are alienated from the state, and oppose its national institutions—could lead to friction between the majority group and the minority and could even deteriorate into violence, which would undermine social resilience and Israel’s national security. Adopting a suitable policy to counter this challenge is vital if Israel is to ensure a diverse society with high levels of identity and resilience. The article proposes ways to develop a municipal model to integrate minority groups and help them connect to the majority, in order to minimize these risks and pave the way for a more cohesive society.

Abstract

Like elsewhere throughout the world, Israel has experienced waves of internal and external migration, and these phenomena have exerted a strong influence on the country’s development, as well as on the phenomenon of acculturation and relations between the majority and minority groups. In the case of Israel, Arab and ultra-Orthodox citizens migrate in an ongoing process into the living spaces of the majority and create mixed spaces. This article examines the influence of these processes of acculturation on social resilience and national security, and explores whether Israel is sufficiently aware of the challenge that these demographic changes create and prepared to address them.

The article surveys acculturation models for absorption of both foreign immigrants and internal migrants from minority groups among the majority group in Western countries, exploring which could be implemented in Israel on a national and municipal level. The assumption is that the rapid growth of minority groups in Israel—including those that do not identify with the national ethos, feel they are outsiders, are alienated from the state, and oppose its national institutions—could lead to friction between the majority group and the minority and could even deteriorate into violence, which would undermine social resilience and Israel’s national security. Adopting a suitable policy to counter this challenge is vital if Israel is to ensure a diverse society with high levels of identity and resilience. The article proposes ways to develop a municipal model to integrate minority groups and help them connect to the majority, in order to minimize these risks and pave the way for a more cohesive society.

Keywords: acculturation, multiculturalism, mixed cities, ultra-Orthodox, Arabs, demography, social resilience.

Introduction: Models of Acculturation and Minority Absorption

Ever-intensifying processes of globalization, as well as internal and international migration, mean that in more and more countries, people from different societies, different nations, and even different continents live in the same geographical space (Segal, 2019). By their very nature, multicultural encounters are charged, especially when dealing with shared lives created in the framework of close urban proximity. This encounter creates a process known as acculturation, in which cultures influence each other in terms of their values and their way of life, and can also lead to confrontations and challenges (Sam et al., 2013).

The field of acculturation was first described more than 130 years ago (Roibin & Nurhayati, 2021) and was studied by various researchers using different theoretical conceptualizations over the past 50 years (Ward & Geeraert, 2016). At first, the acculturation theory sought to describe how “primitive tribes” should adapt themselves to the dominant cultural majority (Rudmin et al., 2017). In those first years, the acculturation model was displayed through one-dimensional lenses, whereby it was expected and preferred that members of the minority group abandon their values, norms, and behavior and adopt those of the majority (Gordon, 1964). Over the years, with greater general sensitivity to the phenomenon of racism, the academic world also began to recognize the virtues of minority groups, and far more inclusive and exact models and theories were developed (Rudmin et al., 2017). One of the models most commonly accepted today was drawn up by John Berry (1990), which enables conceptualization of the processes occurring in the world and in Israel.

According to Berry (1990), members of minority groups have four coping strategies when they come into contact with the majority. Sometimes, the minority will opt to maintain its original culture and differentiate itself from the majority, creating geographic, moral, and ideological “walls” between themselves and the majority (segregation). Sometime, members of the minority group want to be absorbed into the majority or are forced to do so (assimilation). Between these options are two intermediate options, namely, integrating into the majority culture while maintaining the original culture (integration), or abandoning both the minority and majority cultures (marginalization).

Beyond the influence of sociological and psychological variables on the acculturation strategy of the minority group (Trachtengot, 2021), the position of the majority group is a significant factor when it comes to the strategy that the minority group will adopt (Brown & Zagefka, 2011; Giles et al., 2012; Lefringhausen et al., 2022). The dominant approach is that the positions of the majority group with regard to an optimal policy for creating harmony between the groups are the most important factor when it comes to the type of acculturation that the minority group adopts (Vorauer et al., 2009; Whitley & Webster, 2019; Wolsko et al., 2007).

Three Potential Approaches of the Majority Group

- Assimilation: This policy proposes the creation of a homogenous society, which expects members of minority groups to abandon their traditional values and lifestyles and adopt the behavior of the majority group (Berry & Kalin, 1995; Guimond et al., 2013). This approach is similar to the “melting pot” approach prevalent in the first years after Israel’s establishment, which aspired to create a uniform Israeli model, whereby all population groups would come together to create a new Israeli culture that did not previously exist. In the assimilation model, however, the majority group expects that overall, the smaller groups will adopt its culture and abandon other beliefs and lifestyles.

- Multiculturalism: This approach supports recognizing and protecting the singular characteristics of each group, while encouraging harmonious coexistence between the groups (Berry & Kalin, 1995; Hornsey & Hogg, 2000). This approach recognizes that there are “different tribes” in a shared space, and advocates that each continue to adhere to its particular lifestyle. At the same time, this approach urges collaborative and positive relations between the groups, from a stance of mutual acceptance. Policies of this sort are implemented in countries like the Netherlands and Germany, where the state represents a cooperative and equitable framework for members of all groups, allowing each to embrace a singular way of life while cooperating with the other groups in the population. The United States ostensibly also has a multicultural policy, which allows minorities to protect their respective lifestyles, although it is possible that assimilation is so conspicuous there that it does not fear allowing minority groups to retain their singularity while they assimilate into the majority culture.

- “Colorblindness”: This approach is driven by a concern over prejudices and discrimination against the minority group, so it seeks equal treatment for each individual, ignoring any cultural or other affiliation (Rosenthal & Levy, 2010; Wolsko et al., 2000). This approach supersedes the differences and unique qualities of each group and argues that all individuals should be treated equally.

Which Approach Prevents Prejudice and Encourages Acceptance and Equality?

In order to identify how different policies affect prejudices, Whitely and Webster (2019) surveyed 99 different studies (42 from the United States and 57 from various European countries). Their comparative study found that a policy of assimilation tends to lead to a rise in the rate of prejudice, while colorblindness leads to a very slight drop. Multiculturalism also tends to lead to a drop in the rate of prejudice. Studies have shown that these approaches can only exert a positive influence when members of the majority group recognize the lifestyle and values of the minority group, while at the same time aspire to create a society—homogeneous or heterogeneous—that can contain their shared existence as one society. In contrast, when the minority group experiences the majority as objecting to its unique traditions or customs, or not recognizing its legitimacy, it could reject a policy of integration, while adopting insular and isolationist tendencies in order to safeguard its uniqueness (Black, 2021; Bastug & Akca, 2019; Brown & Zagefka, 2011; Zagefka et al., 2012). These cases can spur a phenomenon known as reactive ethnicity. Efforts by the majority group to integrate the minority could be experienced by the latter as efforts to assimilate them and could increase opposition to integration (Rumbaut, 2008).

In the State of Israel, there are two large minority sectors—Arab and ultra-Orthodox. Beyond the obvious differences between them, both tend to perceive in a similar way the behavior of the majority group toward them as an attempt to implement a policy that leads to their assimilation into Israeli society. Notwithstanding the state’s efforts to afford these groups a certain degree of autonomy—in terms of their separate education systems, their exemption from the Israeli “melting pot,” namely, mandatory military service, and relative freedom to maintain their respective cultural lifestyles, especially in homogenous communities—they sense that overall the majority group is not willing to recognize their values and their lifestyles fully or to accept them as legitimate and, in so doing, actually wants to assimilate them. The nature and the perceptions of these groups stem from different catalysts and objectives, but in practice they are similar.

Arab society, which comprises around 20 percent of the Israeli population, experiences an ongoing sense of discrimination within Israeli society (Okun & Friedlander, 2007)— manifested in efforts to minimize the presence of the Arabic language and culture (Wattad, 2021), inequitable distribution of cultural and economic resources (Zussman, 2013), and the state’s failure to recognize the sector’s narrative regarding their national and historic past as part of the Palestinian people (Kimmerling & Migdal, 2003). The Arab minority feels that despite its efforts to connect and integrate while maintaining its lifestyle and its historic affiliation, and despite the state’s significant efforts to integrate Arab society and the cultural, linguistic, educational, and religious autonomy that the Arab minority enjoys, which is among the most extensive in the world, Israeli society as a whole is trying to erase its identity and its heritage within the greater society. Consequently, there is a tendency within Arab society toward isolationism and Palestinianization (Khaizran, 2020). Thus while Arab sector openly declares its drive to integrate into Israeli society, it seems that it harbors a fear of assimilation.

Similarly, ultra-Orthodox society, which comprises around 13 percent of Israel’s total population, is undergoing a similar if not identical process. Concerned lest it be assimilated into the majority population and its unique way of life erased, ultra-Orthodoxy has for many years adhered to a policy of separation and built ever-higher walls between itself and the rest of the population (Brown, 2017). Although this trend has been dominant in ultra-Orthodox society for many years, in the past 20 years, in tandem with and in response to growing efforts to integrate parts of ultra-Orthodox society into the general population, the ultra-Orthodox have been inclined to build even higher walls, to ensure their cognitive sense of being a minority, and to reject any trend toward integration—even if, in the end, it could benefit them. Thus, for example, ultra-Orthodox society refrains from encouraging integration into the workforce or higher education, and anything that might lead to a connection between the ultra-Orthodox population and the general population. Ostensibly, connections would boost the mobility of ultra-Orthodox society, enhance its socio-economic position, and prompt a more positive attitude among the rest of the population (Trachtengot, 2021). However, it seems that the ultra-Orthodox community’s fear of assimilation, like that of the Arab population, is so great that they prefer to segregate themselves, even at the cost of economic and social resources (Friedman, 2021). As a result, a vicious circle is created, whereby the higher walls create a backlash among the Israeli public, which loses patience with the Arab and ultra-Orthodox narratives and finds it hard to accept them. This, in turn, leads to greater seclusion, increases anxiety among the rest of the population, and so on.

According to the acculturation approach, it appears that the Arab and ultra-Orthodox minorities, despite their differences, share an increasing sense of alienation from the rest of the population. This disconnect stems from similar sources and motives, and is due in part to the policy of integration that the majority group implements toward them. This policy does not stop at its desire to integrate them into Israeli society but is accompanied by a lack of acknowledgment of the values of the minority groups and concomitant efforts to erase their cultures and values. The two groups aspire to safeguard their uniqueness and their way of life at any price, so they build walls of separation. This decreases their identification with the Israeli collective and leads to their being more distanced from the majority.

In these circumstances, demographic changes that reduce the geographic distance between these groups and the rest of the population create an emotional distance, which is a source of difficulty and tension. This occurs when the acculturation is not mediated or not managed properly by the authorities. The following section examines various models of acculturation that have been implemented in some other countries.

Models from Countries with Mixed Populations

Canada: Multicultural Model

Canada, where people from different cultures live in close proximity, is a model of a country where there is a strict policy to safeguard the rights of the minority groups that comprise the population (Guo & Wong, 2015). This massive country, the second largest in the world after Russia, covers an area of 10 million sq km, with most of its territory uninhabited. The population of Canada is around 40 million people (about 12 percent of the population of the United States, its southern neighbor), living for the most part in a small swath of land in the south of the country, stretching over a mere 500 kilometers north of the US-Canada border. These figures, coupled with the fact that Canada’s population has comprised diverse cultural groups since Europeans first began settling there (Berry & Hou, 2021), have encouraged immigration, which, in turn, shaped the character of the country and its population. Around half of the Canadians are Christian (53 percent) and only 40 percent belong to the indigenous populations, English or French. This balance continues to change as Canada absorbs more and more migrants from throughout the world. Canada currently absorbs more than 1 percent of its population in immigrants every year, mainly academics and professionals (Bragg & Wong, 2016). Thus, Canada’s population comprises significant minority groups of immigrants from all over the world—from Japan and China to South America. There are more than 200 ethnics groups in Canada, including 13 large groups that number more than 1 million people each.

In 1971, Canada become the first country in the world to adopt multiculturalism as official government policy. The goal was to unite the various groups in Canadian society, in order to relieve tensions between the English and French populations as well as to strengthen other ethnic groups’ sense of belonging to the country (Knowles, 2016). To strengthen the move, in 1982 a new constitution came into effect that included the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which legally enshrines human rights in the country. These two decisions were possible because Canadian culture is characterized by a multicultural approach and open to the existence of different cultures side by side, with the common denominator of a national framework that unifies them all (Brosseau & Dewing, 2018).

These and other points mean that from the outset—and not retroactively—Canada absorbs immigrants as citizens with equal rights and not as guests. As such, the traditional conflicts that arise between the majority that absorbs the newcomers and the incoming minority barely exist. While the Canadian province of Quebec has been home to separatist movements, this in fact illustrates well the effectiveness of the Canadian model, since Quebec previously sought to split from Canada and implement a non-multicultural policy. In general, while Great Britain, France, and other European countries experience problems integrating minority communities into their societies, including Muslim communities, the Canadian example provides a successful model that promotes national unity and social cohesion, while its starting point is equal treatment for all cultures. This is a laudable policy that nurtures shared values, recognizes the different narratives of the cultures that comprise society as a whole, is based on mutual respect, and is supported by legislation that can be endorsed by all the ethnic and religious minorities in Canadian society. One could define Canadian multiculturalism as an approach that seeks to help immigrants and minorities integrate into Canadian society, which the goal of breaching the obstructing barriers. The goal is to facilitate their acceptance into Canadian society and strengthen their Canadian identity.

The institutionalization of multiculturalism means that all the cultures in Canadian society are treated equally, and there is no concern that the integration of different cultures will undermine Canadian law, its institutions, or the character of the country. A survey conducted in 2016 showed that in comparison with other countries, Canada was less affected by the outbreak of anti-Muslim sentiment that is wont to polarize ethnic relations. The survey showed that 83 percent of Canadians agree that Muslims make a positive contribution to the country—findings that are a world apart from similar studies in European countries. The survey also showed that Canadian Muslims report less hostility from their compatriots than Muslims in other countries. As such, the identification of Canada’s Muslim community with the country grows stronger and stronger over time (Beyer & Ramji, 2013).

Unlike Canada, many European countries, particularly France, which follows a policy of colorblindness, experience periods of violent protest by Muslims against the authorities.

France: A Colorblind Model

Under France’s liberal immigration policy, the Muslim population of the country has grown over the past century and now numbers some 7 million people—more than 10 percent of the total population. In recent years, Islam became the second largest religion in France, after Catholicism and far head of Protestantism.

As far back as the 1960s, French President Charles de Gaulle said that integrating Muslim immigrants in France was like trying to join oil and water, since even if they were to live side by side for years, they would not mix. Over the years the government permitted the immigrants to live in religious-cultural ghettos, which developed entirely differently from the state’s objective. France sought economic progress while safeguarding individual rights but saw in these ghettos the good of the group before the good of the individual, which thereby perpetuated the low socio-economic standing of the people living there. This in turn reinforced the stereotypes of the general population toward immigrants and led to their entrenchment as members of the lower classes, alongside the development of negative phenomena such as unemployment, poverty, and crime. It was only a matter of time until the situation boiled over, as occurred in the October 2005 riots (Filiu, 2020).

In terms of their approach to immigrants and migrant populations, Canada and France thus represent different models: multiculturalism versus colorblindness. Immigrants to Canada are integrated in the very center of the experience, the society, and the culture. Their cultural and social development runs in parallel to the development of Canadian cities, Canadian society, and the Canadian mainstream, so fewer gaps and reasons for conflict are created. This integration aims from the outset at the center of the Canadian experience and Canadian culture. In contrast, in Europe and especially France, integration is retroactive and occurs out of a sense that the immigrants are guests, so immigrants and especially Muslims are absorbed into social, economic, and cultural ghettos, which exist separately from the state and its development. The gap between the majority group and the discriminated minority groups engenders frustration, which leads to violence and aggression.

In this context, it is impossible to ignore the fact that many of the Muslim immigrants in France who came from former French colonies, primarily in North Africa, still bear the scars in terms of their relationship to French culture; part of their goal in migrating there is to change France’s character, rather than become integrated into general society. In contrast, immigrants to Canada are, for the most part, middle-class professionals who want to integrate into the local population. It is our contention that a country’s attitude toward immigrants has a major influence on the way they are integrated. Even among an immigrant population that displays separatist tendencies, the multicultural model approach may reduce these tendencies and help build bridges to the general population.

The Israeli Case

Cognizant of the intensity of inter-group tension in Israel, this article does not presume to propose a model that erases the existing conflicts. Rather, the current comparison aims to identify and propose ways of minimizing the intensity of existing conflicts. Like Canada, France, and many other countries with positive net immigration, Israel is a society that absorbs immigrants—as long as they are Jewish—and views their immigration as a paramount national value, vital to the state and society. But while migration in Canada is linked to a socio-economic ethos, which views immigrants as making an important contribution to economic and social prosperity, nationalist and security elements are part of the Israeli ethos, which sees migration, both internal and external, as another vital part of the Jewish people’s grip on different parts of the land (Aharonovich, 2007). The opposite is true when it comes to the Arab minority.

The issue of Israel as a society comprising groups with little harmony between them has occupied sociologists for many years. Sammy Smooha, for example, said that Israeli society is not uniform and comprises three sub-groups: Hebrew, ultra-Orthodox, and Arab. Smooha argued that Israel exhibits a model of descriptive multiculturalism, but normative multiculturalism—like that which exists in various Western countries—has not developed, in part because Israel is “tricultural in essence, but not multicultural in its ethos,” and therefore it is not influenced significantly by post-nationalist and multicultural trends in the West (Smooha, 2007, p. 227). In contrast, others argue that in practice Israel is a binational state, since the Arabs who reside between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River are a very large minority (40 percent) and could be a nation with equal standing (DellaPergola, 2010). Moreover, a survey of Jews of various ages found that members of the millennial generation tend to define their Judaism more as a religion and less as a culture or an ethnic race (Keysar & DellaPergola, 2019), so it is not clear what unites the Jewish population of Israel and whether it is more of a collection of minorities that is not necessarily a unified majority society.

Our goal is to analyze the issue from an acculturation viewpoint, examining the experiences of minorities in Israel and the integration policy implemented as outlined by the authorities.

In terms of acculturation, notwithstanding the differences in foreignness experienced by the various minority groups in Israel, common to them is that paradoxically the outcome of the policy is exactly the opposite of its desired goal. On the one hand, the state invests significant resources in absorbing these groups, be they immigrants from Ethiopia, France, or the former Soviet Union, or be they are ultra-Orthodox; the same is true, to a different extent and in a different manner, especially in recent years, with regard to Arab society. At the same time, the integration policy that the state tries to implement has led to those groups remaining on the margins of society (Shafferman, 2008). Even when the government invests in these group in various areas and helps them obtain professional training and employment, provides them with preferred education opportunities, and helps them with transportation and more, these groups still experience the Israeli mainstream as trying to erase and eclipse them, which, in turn, makes them keep to themselves and remain on the fringes—sometimes even on the militant fringes (Shtoppler, 2012). In practice, despite the heavy investment, the state has not succeeded in finding a place for immigrants who do not have a Jewish, Zionist, and Western narrative in their culture. Although the state does much to aid their absorption, there is a sense that they have to set aside the narratives of their culture and toe the line with the dominant Israeli culture—and that influences their tendency to remain separate.

In general, Canadian authorities do not interfere in immigrants’ decisions on where to settle, giving them the sense that they are part of the core of the Canadian people. In contrast, in Israel, like in Europe, immigrants from overseas and domestic migrants are absorbed in the peripheries. Immigrants who do not come from an established background or who have migrated for demographic reasons are channeled to the (geographical, cultural, economic, and demographic) peripheries, in order to disperse them in places where a Jewish presence is required. This leads them to become weaker in the peripheries and increases their dependency on the state and on national resources (Sever, 2020).

It is easy to understand why Israeli governments try to implement this kind of integration policy. The Jewish state, though it has already existed for 75 years, is still worried about its very survival, for geopolitical and domestic reasons. The country’s leaders jealously guard the narrative that they believe allowed for the establishment of the state in its current format: a Zionist, Jewish, and democratic state that in terms of its values, economy, and society behaves like Western cultures.

This narrative worked well when the majority culture was Ashkenazi-secular (non-religious) and the other groups were small and marginal (Kimmerling, 2001). Over time, that narrative grew foreign and alienating among many groups in the Israeli population, which were growing due to demographic changes. The Arab sector finds it hard to accept the narrative of a Jewish state, especially under the umbrella of the nation-state law. The ultra-Orthodox find it hard to accept the narrative of a democratic state (or, in its earlier incarnations, a liberal democracy) that does not give precedence to stringent religious law. Immigrants from the former Soviet Union found it hard to accept the feeling that Israeli society expected them to abandon their culture and the Soviet lifestyles that were traditional in their countries of origin (Horenczyk, 1996). Immigrants from Ethiopia found it hard to accept a white and European culture that saw them as black and, as such, second-class citizens, with questionable Judaism. Among these groups, identification with the original values of the state—as expressed in its national anthem, messages, and even commemoration of the Holocaust—do not speak to all (Ilani, 2006; Brown, 2017).

It appears that the majority in Israel, especially in relation to its resources, has failed to see this. The fear over losing the Zionist, Jewish, and democratic nature of the State of Israel has led it to cling too staunchly to the founding narrative and to limit even more its own ability to speak directly to the minorities. This increases the sense among these minorities that the state wants to erase their identity and absorb them within the narrative of the dominant group; this, in turn, causes them to become more insular, to distance themselves from society, to identify less with the State of Israel, and to feel a smaller sense of belonging (Omer, 2019; Friedman, 2021). Unlike the Canadian ethos and narrative, which expanded to include as many immigrants and groups as possible, the Israeli narrative is exceptionally narrow and thus alienates significant groups in the country. Although the goal is to safeguard as much as possible the Jewish-Zionist hegemony, paradoxically it appears that the minorities self-segregate and perpetuate the ethos of difference and isolationism. This ethos leads them to educate the next generation not to see itself as a partner to the Israeli narrative. Instead, they behave in such a way to express the values and lifestyles of the minority group to which they belong.

A narrow national narrative is a challenge for minority groups, especially when they are sizable and have an expanding physical presence in various parts of the country. In the absence of a shared national ethos that minorities can or want to embrace, some do not find their frame of reference in the state and do not identify with its goals and values. This could represent a threat to the resilience and security of Israel and even damage its long-term ability to deal with domestic and external challenges.

It appears that Israel’s attempts to build a shared narrative and absorb minority groups in the social center is not particularly successful and the trend toward isolationism is expanding. The state must view this as a national challenge. It is possible that change will come from the local authorities, which could spearhead the activities necessary to generate the kind of socialization needed for the integration and prosperity of minority groups in Israel. The more they adopt appropriate models for cities with mixed populations that offer frameworks to absorb minority groups equitably in the societal center and build a shared fabric of life, the more they will become models for the central government.

Absorbing Minority Groups in Israeli Cities with Mixed Populations

Israel’s population is concentrated in a densely populated and rapidly developing area in the center of the country. Demographic growth leads to evident changes, which in turn have ramifications on the urban space on the local and national levels. Inter alia, there is an increasingly prevalent phenomenon of mixed-population cities in an ongoing and intensifying trend of citizens from different communities living in close proximity to each other, notwithstanding polarization in terms of values, religion, culture, and socio-economic standing. Demographic growth and changes can be an opportunity for positive renewal, but they also incur the danger of social decay, chasms, friction, and mutual violence. More than 20 central Israeli cities and towns, including the capital Jerusalem, are already deep into a process of significant and rapid demographic change. The housing crisis and other socio-economic processes have led to specific sectors, like the ultra-Orthodox and the Arabs, to move in significant numbers to cities with mixed populations, which increases their proportion in these mixed cities, including those that were largely homogenous in the past.

The violent confrontations in May 2021 between Jews and Arabs in mixed cities, like the conflicts in other spaces and cities where the minority is growing, focus public attention on the negative phenomena that also relate to national security. These phenomena, which presumably will continue, perhaps even intensify, require both forceful responses from enforcement agencies and softer socio-economic responses. Only thoughtful, long-range, and systemic socio-economic handling of the challenges posed by these phenomena will lead to a positive model of “absorption in the center,” which would reduce dangerous friction. To ensure that the expected trend of integrating populations with specific cultural characteristics is successful and becomes an engine of renewal and growth, the state and the local authority must intervene in the phenomenon at many stages and on many levels. At the same time, correct groundwork in cities could presumably allow for the implementation of a sound model for coexistence on the national level as well. Currently, Israel is not doing what it should to address the issue, and the absence of a systemic policy could turn Israel into a country in which day-to-day life is primarily characterized by violent domestic polarization. Moreover, Israel’s public systems are not built in any way to deal successfully with this threat.

The following are some examples of models of integrating minority groups in mixed Israeli cities. These can serve as a source for what is needed for positive and effective socialization.

Beit Shemesh: A Victim of Poor Planning

For many years, Beit Shemesh was a small town of people with a traditional-Mizrahi orientation. Despite its central geographical location between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, Beit Shemesh was only a hub for smaller adjacent communities, limited to the area. In the 1980s, the community’s growth potential was evident, and two neighborhoods were erected in its eastern portion for an ultra-Orthodox population. Within a decade, the population of Beit Shemesh doubled and it was declared a city in 1991, while the number of residents exceeded 20,000 (Busso, 2017). At the same time, the Housing Ministry announced the start of work on Ramat Beit Shemesh, a huge series of neighborhoods, each with more residents than the parent city (Vardi, 2017).

At the time no one thought about a comprehensive plan to deal with the demographic change. The likely assumption was that the ultra-Orthodox population would “get along” with the local, traditional population and that social harmony would prevail of its own accord. Also missing was a considered discussion about planning workplaces tailored for the hundreds of thousands of ultra-Orthodox people who would be moving to the city. Similarly, there were no preparations for the ramifications of Beit Shemesh becoming one of the largest cities in Israel, expected in the coming decade (Regev et al., 2021). In the absence of any infrastructural, social, or economic preparation, within a number of years the city found itself in a culture war between the population groups (Stern, 2018) and in ever-increasing economic distress (Tzur, 2019).

The current population of Beit Shemesh is more than 150,000 (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2023). In the coming years, the population will likely double as people start to move into the huge neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city that are currently under construction. Although there is now greater awareness of the importance of the socio-economic development of the city, and the government recently approved a resolution allocating huge sums of money for development projects in the city through various ministries, it seems that this is a case of too little, too late. The city is still plagued by many social rifts, and it seems that it will take many years to rectify the situation (Haimovich, 2011). There are tensions, even confrontations, between the various groups that share the city: conflicts between more radical ultra-Orthodox factions, which want to change the character of the city, and more moderate members of the ultra-Orthodox community (Sever, 2022); between the ultra-Orthodox community and the other communities for control of the city and its resources (Gal, 2022); ongoing conflicts between the authorities and groups of residents (Cohen et al., 2021), which peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic (Cohen, 2020); and even racial tensions between veteran Mizrahi residents of the city and the recently arrived Ashkenazi residents (Ben-Simon, 2004). Moreover, there are increasing shortages of employment opportunities tailored to the specific population of the city and of economic stimuli to aid the growth of the city.

As of 2013, there were more than 20 important Israeli cities that undergoing significant demographic changes, some just as rapidly as the change experienced by Beit Shemesh. Cities like Ashdod, Safed, Tiberius, Kiryat Malachi, Kiryat Gat, Ofakim, Netivot, and Arad have seen a rapid intake of an ultra-Orthodox population, and cities like Harish, Ma'alot-Tarshiha, Carmiel, Acre, Ramle, and Nof Galil have seen a rapid intake of an Arab population (Even, 2021). These migratory groups grow both because of a high birth rate and because the consolidation in new locations lays the infrastructure for many others to follow them. Within a relatively short period, they are likely to become the largest and most prominent groups in most of these cities.

The Current Situation in Cities with a Large Ultra-Orthodox and Arab Populations

There are differences between the dynamics of the demographic changes of the ultra-Orthodox and the Arab populations (Tables 1 and 2). Arab society is undergoing a process of rapid natural population growth. The growth rate in ultra-Orthodox society stands at 4.2 percent, while for the general population it is just 1.8 percent. This means that every 17 years the ultra-Orthodox population will double in size (Cahaner & Malach, 2021). While it is true that there has not been a significant natural rise in the population of the Arab community, where the birth rate has actually dropped in recent years and is now similar to that of the non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish population, the Arab population migrating to mixed cities is much younger, which means that the proportion of Arabs in these cities is expected to grow in the coming years (Knesset Research and Information Center, 2021).

Table 1: Total population and the proportion of ultra-Orthodox in selected cities

| City | Total population | Ultra-Orthodox population | Ultra-Orthodox population rate |

| Beit Shemesh | 152,781 | 96,400 | 63% |

| Safed | 38,033 | 20,370 | 53.5% |

| Netivot | 45,530 | 21,895 | 48% |

| Givat Ze’ev | 21,026 | 9,550 | 45% |

| Ofakim | 35,258 | 12,420 | 35% |

| Arad | 27,986 | 8,080 | 29% |

| Ashdod | 226,798 | 56,150 | 25% |

| Haztor Haglilit | 9,986 | 2,390 | 24% |

| Kiryat Malachi | 25,500 | 6,100 | 24% |

| Tiberias | 48,202 | 10,320 | 21.5% |

| Kiryat Gat | 63,559 | 12,850 | 20% |

Source: Combined analysis of December 2022 data from the Central Bureau of Statistics, the Haredi Institute for Public Affairs, and reports from the local authorities

Table 2: The total population and the proportion of Arabs in selected cities

| City | Total population | Arab population | Arab population rate |

| Nof Galil | 43,890 | 12,680 | 28.9% |

| Acre | 50,846 | 14,084 | 27.7% |

| Ramle | 78,479 | 21,267 | 27.1% |

| Lod | 85,141 | 20,093 | 23.6% |

| Ma'alot-Tarshiha | 22,399 | 4,636 | 20.7% |

| Carmiel | 46,884 | 9798 | 20.1% |

| Harish | 32,770 | 4587 | 14% |

Source: Combined analysis of December 2022 data from the Central Bureau of Statistics and reports from the local authorities

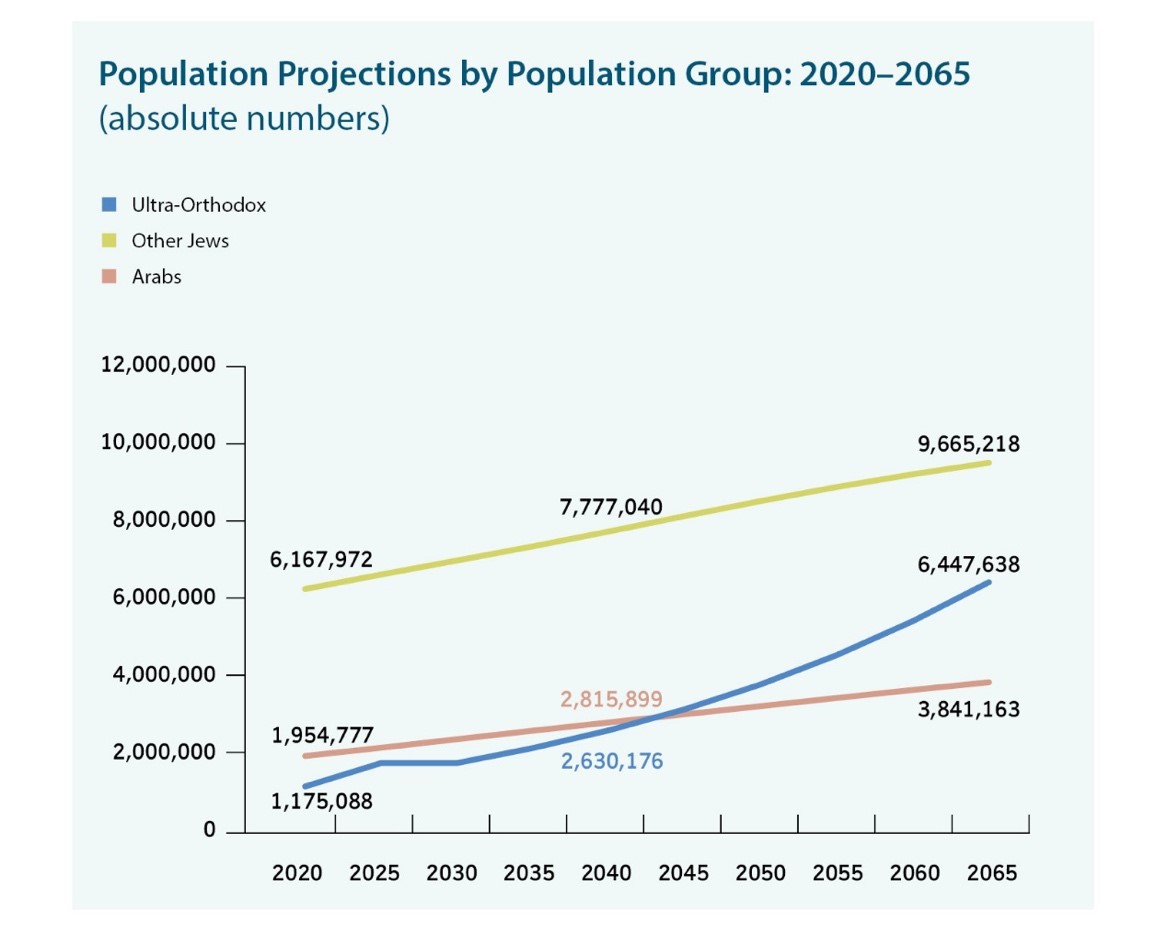

Figure 1: Projected growth for various populations in Israel

Source: The Yearbook of Ultra-Orthodox Society 2021, Israel Democracy Institute

Two important phenomena also have a significant influence on these demographic processes: the housing crisis in ultra-Orthodox society and the decrease in the sense of personal security in the Arab sector, because of the sharp increase in violence and crime. These are reflected in the demographic trends of the two communities: until recently, 85 percent of the ultra-Orthodox population lived in the center of the country. Now, however, with the shortage in housing for young couples, many are moving to the northern and southern peripheries and to cities that thus far did not have an ultra-Orthodox population (Regev & Gordon, 2020). At the same time, among the Arab population, which is suffering from an extreme crisis linked to a decline in personal security, there is a marked trend of migration to Jewish cities, in an attempt to move away from places perceived as dangerous (Abraham Initiatives and the Neaman Institute for National Policy, 2021). Among the other factors influencing this trend is presumably the housing crisis in Arab communities, resulting from a shortage of land (State Comptroller, 2019). In addition, the improved economic situation of Arab society allows many more to move to cities that in the past were characterized as Jewish cities (Ron et al., 2022).

How will these changes influence the populations of the cities absorbing the Arab and ultra-Orthodox newcomers? Will the cities be able to leverage the opportunity and the diversity for growth and prosperity? Below are three models for mixed Jewish-Arab cities: the Lod model, where the integration approach was tried, but merely increased segregation between the two populations, as well as violence and aggression; the Ma'alot-Tarshiha model, which was a multicultural model that respected the Arab minority and its traditions; and the Carmiel model, a successful multicultural model in which a strong Jewish minority lives among an Arab majority in the region.

Mixed Cities in Israel: Three Models

The Lod Model: A Negative Model of Attempted Integration

The city of Lod can be described as a negative case study of the outcome of the policy of integration, which led to a rapid demographic change and ramifications that pose a major challenge for the city. In 1946, two years before the establishment of the State of Israel, there was an overwhelming Arab majority in the city (99.7 percent). When Israel was established, certain measures, some controversial, were taken to remove Arabs from the city and it became almost exclusively Jewish. Since 1972, when the Jewish community made up around 90 percent of the population (Yaacobi, 2003), the Arab population in the city climbed steadily, in part after Arab families were moved to the city—some of them the families of collaborators for whom no other residence could be found. So, for example, after the Six Day Way, the families of Arabs who had helped Israel were relocated from the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. After the peace treaty with Egypt and the evacuation of the Sinai Peninsula, groups of Bedouins whose lands in the Negev were appropriated by the state were also moved to Lod (Research, 2014). In the early 1990s, in the aftermath of the Oslo Accords, more families of collaborators were moved to the city (Hofnung, 2010). Moreover, according to the 2012 State Comptroller’s Report, many Arabs moved illegally to the city from the West Bank, although it is not clear what proportion of the city’s population they comprise. These trends mean that of the city’s current population of around 85,000, 30 percent are Arabs (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2023).

The arrival of a large Arab population in Lod in the 1970s and 1980s was the result of a desire to create a model of multiculturalism in which Jews and Arabs could live harmoniously. The veteran Arab population of Lod, which made up around 10 percent of the city’s population, and its old neighborhoods, which were in the Oriental style, prompted policymakers to believe that the new Arab population that would be moved to the city would be integrated into the local fabric of life and would be a positive model for other cities.

In practice, exactly the opposite happened. The desire to integrate Arab residents, who came from a different background and different cultures, without giving their culture and their traditions any respectful presence or expression in the public space, increased their antipathy toward the authorities and friction with the Jewish community. In turn, this led to increased socio-economic gaps between Jews and Arabs. The poverty rate among the Arab population continued to grow, and with it, so too did phenomena of delinquency, crime, and violence. For several decades, municipal leaders “fell asleep at the wheel,” failing to address the demographic ramifications of the city’s development. By the time of the second intifada, which began in 2000 and saw a marked increase in the amount of nationalist violence in the city, they finally recognized that the integration policy was leading to a dire crisis.

A new nadir came in May 2021, during Operation Guardian of the Walls. For several days, the city was rocked by violence and vandalism, including gun battles in the streets and mob attacks on residents (Blumental & Grinberg, 2021). A civil state of emergency was declared in the city and, for the first time ever, a night curfew was imposed. Armed gangs of Jews and Arabs roamed the streets, and the city was paralyzed for several days (Senyor, 2021). These events exposed the deep national and religious chasm into which the city had fallen.

Currently, Arab residents of Lod feel that the authorities are trying to push them out, both culturally and physically, by encouraging their departure from the city (Gazit, 2022; Haj Yahya, 2023; Shimoni, 2022). These residents report that there is a basic shortage of fundamental amenities in the city. This is in addition to neglect, a sense of discrimination, frustration, insecurity, and despair, all of which contribute to a reluctance to organize and stand up for their rights in the face of the authorities (Shelah, 2022). Although there has been some development momentum in recent years, it is primarily geared toward the Jewish sector. This includes encouraging the expansion of the garin Torani (core group of families from the religious Zionist community) that the current mayor helped found—but this in turn only exacerbates the frustrations of the Arab residents of the city. It seems that the desire to integrate the Arab residents in the Jewish life of the city, without giving any room to their culture and traditions, and was replaced in 2000 by efforts to reject them and limit their involvement in various aspects of municipal life, has deepened the chasm and turned the city into a negative case study and an explosive situation.

The Ma'alot-Tarshiha Model: A Positive Model of Multiculturalism

There is no doubt that preparation and early planning can be the key to the successful migration of minority groups to a city. An example is the city of Ma’alot-Tarshiha, where Jews and Arabs coexist harmoniously, the national conflict notwithstanding (Falah Saab & Abu Laban, 2021). The city is home to secular, religious, and ultra-Orthodox Jews, immigrants with no defined religion, Muslim Arabs, and Christian Arabs, and the city functions well, with mutual respect and cooperation between the communities.

Table 3: Population distribution in Ma’alot-Tarshiha by religion and nationality

| Group | Percentage of the population |

| Secular Jews | 37% |

| National religious | 26.2% |

| Ultra-Orthodox | 3.5% |

| Muslim Arab | 10.3% |

| Christian Arab | 10.1% |

| Druze | 0.3% |

| Others | 12.6% |

Source: Combined analysis of October 2022 data from the Central Bureau of Statistics and reports from the local authority

Ma’alot and Tarshiha were originally two adjacent communities, until it was decided in 1963 to unify them into one municipal authority. Since the 1950s, Jews and Arabs lived side by side in Tarshiha, while Ma’alot was a Jewish community. The unification of the two communities left an Arab center in Tarshiha and a Jewish center in Ma’alot, but it also attracted diverse communities to all parts of the city. Not only does the Ma’alot-Tarshiha authority not try to exclude any part of the population, as happens in other cities; it provides a municipal framework to balance between the lifestyles of the different populations and safeguard the economic and social prosperity of the city. The council also encourages joint conferences to enhance and empower the communal lives of the various populations. Since 1994, when Ma’alot-Tarshiha was recognized as a city, it has been led by equal and shared management, which manages to safeguard the distinctions and qualities of each community (Abraham Initiatives, 2020).

An intercity highway connects the center of the city, which is mainly populated by Jews, and Tarshiha, where the majority of the population is Arab. There are separate education systems, community centers, and even the budget for the different parts of the city appears in separate chapters of the authority’s reports (Galili & Nir, 2001). Nonetheless, Ma’alot-Tarshiha residents participate in joint events, have a common commercial existence, and share entertainment venues (Knesset Research and Information Center, 2021). They are proud of their coexistence, have a very positive attitude toward their city, and even recommend it as a model for coexistence that has proven itself (Falah Saab & Abu Laban, 2021). The large wave of immigrants that came to the city in the 1990s from the former Soviet Union, which tilted the demographic balance in the city in favor of the Jewish population, did not upset the harmony and the desire of residents to progress and develop side by side (Arshid-Shehadeh, 2022). In the past few years, new neighborhoods have sprung up on the outskirts of the city, where Jews and Arabs live in close proximity, and the overall atmosphere in the city influences the quiet and tranquil life there. For example, in the Zeitim neighborhood in the north of the city, there is a large community of newly religious ultra-Orthodox living alongside the 30 percent of the neighborhood that is Arabs (Knesset Research and Information Center, 2021; Rath, 2022).

The Carmiel Region Model: When the Majority becomes the Minority

Although just 20 percent of the population of Carmiel is Arab, in the geographical space surrounding the city Jews are a minority. The city is a commuter hub for many Arabs from the surrounding villages and Carmiel’s municipal infrastructure serves more Arabic speakers than Hebrew speakers.

Although the city was established as a secular Jewish community in order to Judaize the Galilee and interrupt a contiguous Arab presence from Acre to Safed, the families of soldiers from the South Lebanese Army who were relocated there after Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon, along with slow but incessant migration of local Arab residents, turned it into a mixed population city with an ever-growing Arab population. The Jewish population too is not homogenous. From the start of this century, more ultra-Orthodox people moved to the city and now make up 10 percent of the population.

Nonetheless, life continues harmoniously in the city, and even when the rest of the country is beset with Jewish-Arab tensions, Carmiel has remained relatively calm, largely because the city opened its doors to Arabs almost without any restrictions. Arabs live in every part of the city, side-by-side with Jews, and they can be seen together in the city’s commercial, entertainment, and leisure centers (Nardi, 2017). The housing crisis in adjacent Arab communities, coupled with a growing number of educated young Arabs looking for quality housing in a city, has led to a rise in the Arab population in Carmiel (Oraby, 2020).

However, Carmiel still does not have an Arab education system or religious services for the Muslim population (Rosen Haberman, 2016). This means that there is movement in both directions between the city and the adjacent communities: people flock to the city for housing, employment, and leisure, and from the city to educational and religious institutions in the villages (Blatman-Thomas, 2018). Similarly, it is impossible to ignore certain elements within the city’s population who object to the arrival of Arabs; for the time being, these are marginal elements, however, and the need for functional coexistence gains over these voices (Nardi, 2017).

The more Arabs live in Carmiel and the longer the people running the city insist on a policy of integration without making the Arab lifestyle and culture more present in various public spaces, the more chance there is of conflict and confrontation ending the coexistence that residents enjoy today.

Recommendations for Municipal Preparedness for Integrating Minority Groups

While the model does not presume to resolve Israel’s existing conflicts in ideal fashion, we believe that it can significantly reduce the volatility of the current situation between the various groups in Israel. Moreover, it can help groups ostracize radical fringes that seek to spark conflict. Again, this is not a perfect model that can resolve all issues when minority and majority populations live side by side; rather, it is a suggestion for reducing conflict in those places where it can be implemented. This article, therefore, does not address the issue of Jerusalem as a mixed city, which is a national, cultural, societal, and economic challenge that must tackle not only sectorial conflicts but also multinational and other disputes. The question, rather, is how the Ma’alot-Tarshiha model can be replicated in additional communities, in which tensions are high between the various communities.

- Can advance preparedness by the government and the local authorities significantly promote coexistence?

- How can we ensure that the changes in these cities bring growth and innovation, rather than greater social division—as happened in Beit Shemesh and Lod?

- What economic and social preparations are needed to deal with far-reaching urban demographic changes?

It appears that without proper preparations that take into account all the populations and combine them in a municipal multicultural model, societal conflicts will intensify until they reach the point of widespread violence. What follows, therefore, are some points relating to the local authorities’ preparations for absorbing minority groups, both due to demographic changes and migration, and for a situation in which the population of the city is heterogenous and includes groups that are in states of conflict with each other:

A multicultural policy views migrants who move to the city as a welcome part of the fabric of life, who will contribute to its prosperity and advantages. This is a liberal policy that expands the urban ethos and vision and includes all the groups living in the city. This creates a strong sense of belonging for each group in the city, urban identification becomes stronger, and members of all the groups work together for the development of the city.

Indeed, from the survey above, it seems that the multicultural policy would be best for the absorption of immigrants and minority groups in Israel. The gulfs that exist today, be it the religious divide when it comes to the ultra-Orthodox population or the nationalist divide when it comes to the Arab population, as well as the vague Israeli identity among various minority groups that seeks to stand apart, obligate adopting a multicultural policy that affords space for all these groups and enables them to express their specific identities as part of Israeli society. To this end, Israel must integrate the minority groups to make them part of the urban ethos and vision, and urban planning must take their presence into account. Similarly, their integration must be at the very heart of the urban experience, and not the margins. Their lifestyles and their worldviews must be present in the public and central space from the outset and not retrospectively, even when these worldviews are not comfortable for the dominant Israeli narrative, which is Jewish-Zionist-Western in nature. Municipal leaders must adopt a lateral approach rather than a hierarchical one, so that all the groups that make up the population of the city, including activists on the ground, can make their voices heard in the leadership of the city and its plans for the future.

Empowering the leadership of groups integrating in the city: We tend to see groups as one entity, in accordance with prevalent stereotypes, but every group has segments that assume responsibility and want to play an active role in the prosperity and development of the city, while there are those who participate less. In every group, there are those who make up a solid economic base and contribute more to the city, and there are those who contribute less. The authorities should chart the various groups to understand with which parts of the population it is possible to work for the advancement of the city. The local authority must be able to work with those groups on assuming responsibility and leadership, and it must give them the tools to help lead the city to growth and prosperity. Empowering these groups and giving them leadership tools, in order to allow the activists among them to spearhead a process of integration and a greater sense of commonality, could turn the demographic changes these cities are facing into a constructive and empowering reality.

Employment tailored to the population: The more diverse the population, the more employment must be tailored to the target audience. For example, in ultra-Orthodox society there are some people who are interested in working in white collar academic professions, and there are those who want to obtain an education that will allow them to gain employment in simpler, blue collar professions (Employment: Key Indices, Employment Bureau, n.d.). There are some communities in which women go out to work and have careers as managers or executives, and there are some communities where it is more acceptable for the men to work and provide for the family (Ashkenazi, 2022). There are groups that prefer employment within their own community, while others are willing to work in heterogenous environments. There are groups that prefer to work in innovative environments that are rich in technology, while others are less inclined to innovative technology and prefer to work in simpler, technical occupations (Peleg-Gabai, 2022).

In Arab society too, there are different classes and specific branches of employment preferred among the population. In an era in which the proportion of Arabs with academic qualifications is increasing and many obtain training in hi-tech professions, it is noticeable that many fail to find suitable places of employment in their communities (Jabareen, 2010). The need to adapt training and employment for the target audience must be of concern to the government and the local authority the moment that significant demographic change is identified. Municipal leaders must identify the preferred branches of employment among the populations and bring suitable employees and training to the city (Regev, 2017). Similarly, they must identify the employment strong points of each group and divert employment resources in the city to these strong points, which might be different from the existing ones (Jabareen, 2010). They must work closely with employees to ensure that they employ these populations and understand the advantage of integrating them and the diversity that this brings to their business (Stein et al., 2022). Clearly, this process must be done with cooperation of the public and the community leadership so that they belong to and lead this process, rather than its being an imposition on them.

Early mapping and distribution of public, educational, cultural, and leisure facilities: A demographic change to the population of a city brings new needs in the fields of education, culture, and leisure. This could lead to a situation in which the use of certain public buildings is limited, while at the same time, there is an increasing shortage of buildings serving other populations and purposes (State Comptroller’s Report, 2022). Various local authorities have put the need to deal with this difficulty at the bottom of their agendas and prefer to find simple solutions like using mobile homes, which leads to social divisions and to an ongoing sense of discrimination among parts of the population (Ben Zikri, 2016). Early mapping of these needs and reaching agreements with groups and communities about the exchange of buildings and compensations, which must be done as an advance process and with mutual agreement, is vital for continued harmony in the city. Thus, for example, groups that find that the educational facilities are empty would be happy to turn those buildings over to younger populations, if and when they are given in exchange access to leisure and culture facilities that suit the age group of their members. The leisure activities of groups that depend on specific hours or seasons can share those buildings with other groups, who have needs at different times. In these cases, the authority will convey that no one group is served at the expense of others, rather, that each of the populations receives and gives in exchange, when the division is in accordance with the needs and the common good of the whole population (Shaked, 2021). This can reduce potential fear of one group’s growth and help the various groups see the local authority’s leadership as objective, which puts the good of the city as a whole first and acts accordingly.

Equal treatment for each population group: Leaders of city in which the population is changing tend to become anxious about the growing population, and try to limit the arrival to the city by negating the legitimacy of the group, stressing its negative characteristics and barring its members from certain parts of the city. Under these conditions, the growing population develops a reaction toward the city’s leadership, which widens the gaps and halts the city’s development (Perez-Vaisvidovsky, 2013). An authority that broadcasts openness and positivity toward groups in the city that are interested in coexistence (rather than doing so to extremist and isolationist groups that do not recognize the symbols and institutions of the state, since that would come at the expense of others), and is capable of highlighting the strong points of each of the groups, while insisting on clear criteria to help the city’s development, will reap the benefits of a diverse population and continue to prosper, demographic changes notwithstanding.

In order for the conclusions presented in this article to be adopted, the government and local authorities must first recognize the importance of the matter and understand the dangers that lie in the lack of a comprehensive policy that deals successfully with the challenges that exist in a city with mixed populations. Against the backdrop, they must prepare in advance for the needs of the changing demographic situation in their city, as the basis for building coexistence even in circumstance of local heterogeneity—thereby improving the lot of such cities. Early preparations will help transform from centers of conflict and chaos to spaces of cooperation, empowerment, and prosperity. This would have a positive influence not only on mixed cities, but on the state as a whole, which is gradually becoming a mixed space. Alternatively, failure to prepare properly will lead to the deterioration of the mixed cities into violence on all fronts and socio-economic regression, including in the mixed national sphere.

References

Abraham Initiatives (2020). From mixed cities to shared cities: The second mixed city conference [Video, conference proceedings]. https://tinyurl.com/zpesa2bu [in Hebrew and English].

Abraham Initiatives and Neaman Institute for National Policy (2021). Personal security survey for mixed cities for 2020. https://tinyurl.com/mmktbmdx [in Hebrew].

Aharonovich, Y. (2007). Models of urban planning in migrant societies: Multiculturalism versus integration (Doctoral dissertation). Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

Arshid-Shehadeh, M. (2022, July 7). Arabs in a mixed city? It depends on the sample and the approach. Globes. https://tinyurl.com/yrf5zsr9 [in Hebrew].

Ashkenazi, B. (2022, June 14). Work less and earn less: Ultra-Orthodox employment report revealed. Walla. https://tinyurl.com/yewzzp9w

Bastug, M. F., & Akca, D. (2019). The effects of perceived Islamophobia on group identification and acculturation attitudes. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie, 56(2), 251-273. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12245

Ben-Simon, D. (2004, July 18). The rabbis have marked Beit Shemesh. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/4u3z6pw6 [in Hebrew].

Ben Zikri, A. (2016, August 31). Court delays construction of ad hoc classrooms for ultra-Orthodox in secular school in Kiryat Gat. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/46y3x4ze [in Hebrew].

Berry, J. W. (1990). Acculturation and adaptation: A general framework. In W. H. Holtzman & T. H. Bornemann (Eds.), Mental health of immigrants and refugees (pp. 90–102). Hogg Foundation for Mental Health.

Berry, J. W., & Hou, F. (2021). Immigrant acculturation and wellbeing across generations and settlement contexts in Canada. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 33(1–2), 140-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2020.1750801

Berry, J. W., & Kalin, R. (1995). Multicultural and ethnic attitudes in Canada: An overview of the 1991 national survey. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 27(3), 301-320. https://doi.org/10.1037/0008-400X.27.3.301

Beyer, P., & Ramji, R. (2013). Growing up Canadian: Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists (Vol. 2). McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP.

Black, S. (2021). Gaps in the cultural integration expectations between the individual and the group: The ultra-Orthodox in Israel (Doctoral dissertation). Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Blatman-Thomas, N. (2018). Locals, not residents: On the mixed experience of a Jewish city in the Galilee. Israeli Sociology, 19(2), 52-73. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26725429 [in Hebrew].

Blumental, I., & Grinberg, H. (2021, December 2). Two Lod residents accused of shooting attacking during Guardian of the Walls. Kan. https://tinyurl.com/mt5npyuw [in Hebrew].

Bragg, B., & Wong, L. L. (2016). "Cancelled dreams": Family reunification and shifting Canadian immigration policy. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 14(1), 46-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2015.1011364

Brosseau, L., & Dewing, M. (2018). Canadian multiculturalism (Publication no. 2009-20-E). Library of Parliament.

Brown, B. (2017). The Haredim: A guide to their beliefs and sectors. Israel Democracy Institute, Am Oved [in Hebrew].

Brown, R., & Zagefka, H. (2011). The dynamics of acculturation: An intergroup perspective. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 44, pp. 129-184). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385522-0.00003-2

Busso, N. (2017, January 8). Ultra-Orthodox metropolis. TheMarker. https://tinyurl.com/2fc8tk5u [in Hebrew].

Cahaner, L., & Malach, G. (2021). The yearbook of ultra-Orthodox society 2021. Israel Democracy Institute. [in Hebrew].

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). (2023). Population data. https://tinyurl.com/bvy2uy3j[in Hebrew].

Cohen, G. (2020, April 28). Children threw stones and shouted “Nazi”: Clashes in an under-curfew neighborhood of Beit Shemesh. Ynet. https://tinyurl.com/4zjknytm [in Hebrew].

Cohen, G., Rubinstein, R., & Nahshoni, K. (2021, January 12). Clashes and shooting in the air near a Talmud Torah in Beit Shemesh: “Crossing a red line.” Ynet. https://tinyurl.com/2nk854nb [in Hebrew].

Employment: Key indices. (n.d.). Haredi Institute for Public Affairs. https://tinyurl.com/4b7y39na [in Hebrew].

Even, S. (2021). The national significance of Israeli demographics at the outset of a new decade. Strategic Assessment, 24(3), 28-41. https://tinyurl.com/2s3k74t2

Falah Saab, S., & Abu Laban, N. (2021, June 17). Mixed communities that did not experience violence try to explain why. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/2surr8xp [in Hebrew].

Filiu, J.-P. (2020, December 2). The long and troubled history of the French republic and Islam. Newlines Magazine. https://tinyurl.com/2zd2az85

Friedman, S. (2021). Israel and the ultra-Orthodox community: Growing walls and a challenging future. Israel Democracy Institute.

Gal, S. (2022, April 13). “The secular are clueless; in the end they will leave”: The fight over the neighborhood the state. N12. https://tinyurl.com/ycx7e7hj [in Hebrew].

Galili, L., & Nir, O. (2001, April 3). No romance, no hostility. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/dd3b2vxj [in Hebrew].

Gazit, A. (2022, April 13). Petition claims Lod erecting barrier between Jews and Arabs. Calcalist. https://tinyurl.com/yju7pd3w [in Hebrew].

Giles, H., Bonilla, D., & Speer, R. B. (2012). Acculturating intergroup vitalities, accommodation and contact. In J. Jackson (Ed.), Routledge handbook of language and intercultural communication (pp. 244–260). Routledge.

Gordon, M. (1964). Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion, and national origins. Oxford University Press.

Guimond, S., Crisp, R. J., De Oliveira, P., Kamiejski, R., Kteily, N., Kuepper, B., Lalonde, R. N., Levin, S., Pratto, F., Tougas, F., Sidanius, J., & Zick, A. (2013). Diversity policy, social dominance, and intergroup relations: Predicting prejudice in changing social and political contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(6), 941-958. https://tinyurl.com/4maptx7m

Guo, S., & Wong, L. (Eds.). (2015). Revisiting multiculturalism in Canada: Theories, policies and debates. Springer.

Haimovich, M. (2011, December 27). Mr. President, run to Beit Shemesh. NRG. https://tinyurl.com/rnu4eujb [in Hebrew].

Haj Yahya, D. (2023, January 9). Lod municipality offering scholarship to students but makes it hard for Arab residents to receive one. Haaretz. https://tinyurl.com/3att8jva [in Hebrew].

Hofnung, M. (2010). The price of information: Absorption and rehabilitation of security establishment collaborators in Israel's cities. Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Horenczyk, G. (1996). Migrant identities in conflict: Acculturation attitudes and perceived acculturation ideologies. In G. M. Breakwell & E. Lyons (Eds.), Changing European identities: Social psychological analyses of social change (pp. 241-250). Butterworth-Heinemann.

Hornsey, M. J., & Hogg, M. A. (2000). Assimilation and diversity: An integrative model of subgroup relations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_03

Ilani, O. (2006). The identity of immigrants from the former Soviet Union. In O. Ilani (Ed.), Religion and state in Israel (pp. 60-62). Education Ministry [in Hebrew].

Jabareen, Y. (2010). Arab employment in Israel: The Israeli economy’s challenge. Israel Democracy Institute [in Hebrew].

Keysar, A., & DellaPergola, S. (2019). Demographic and religious dimensions of Jewish identification in the US and Israel: Millennials in generational perspective. Journal of Religion and Demography, 6(1), 149-188. https://doi.org/10.1163/2589742X-00601004

Khaizran, Y. (2020). Arab society in Israel and the “Arab spring.” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 40(2), 284-301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602004.2020.1777664

Kimmerling, B. (2001). The end of Ashkenazi Hegemony. Keter [in Hebrew].

Kimmerling, B., & Migdal, J. (2003). The Palestinian people: A history. Harvard University Press.

Knesset Research and Information Center (2021, May 27). Arabs in the mixes cities: An overview. https://tinyurl.com/5yh8x7a5 [in Hebrew].

Knesset Research and Information Center (2022, June 13). Ultra-Orthodox employment: An overview. https://tinyurl.com/ch8mvup5 [in Hebrew].

Knowles, V. (2016). Strangers at our gates: Canadian immigration and immigration policy, 1540–2015. Dundurn.

Lefringhausen, K., Marshall, T. C., Ferenczi, N., Zagefka, H., & Kunst, J. R. (2022). Majority members’ acculturation: How proximal-acculturation relates to expectations of immigrants and intergroup ideologies over time. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302221096324

Nardi, G. (2017, May 2). City in denial: Carmiel is becoming a mixed city. Globes. https://tinyurl.com/yc8d7vx6 [in Hebrew].

Nardi, G. (2017, September 26). Hidden Beit Shemesh: The city’s secret “non-ultra-Orthodox” neighborhood. Globes. https://tinyurl.com/3pkysdkk

Okun, B. S., & Friedlander, D. (2007). Educational stratification among Arabs and Jews in Israel: Historical disadvantage, discrimination, and opportunity. Population Studies, 59(2), 163-180. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720500099405

Omer, F. (2019). Between identity and gender in the Arab sector. Israel Democracy Institute. https://tinyurl.com/8sec8enx [in Hebrew].

Oraby, A. (2020, December 23). We were pushed into Jewish cities; we have no choice. Ynet. https://tinyurl.com/3rndksbs

Peleg-Gabai, M. (2022). Ultra-Orthodox employment: An overview. Knesset Research and Information Center [in Hebrew].

Perez-Vaisvidovsky, N. (2013). The struggle against the ultra-Orthodox in Jerusalem bolsters the control of the ultra-Orthodox leadership. Black Labor. https://tinyurl.com/3axc4xcp [in Hebrew].

Prof. Sergio DellaPergola: The State of Israel is neglecting safeguarding the Jewish majority (2010, September 19). Kan Israel. https://kanisrael.co.il/16412 [in Hebrew].

Rath, R. (2022, September 18). Do newly religious people need a separate community? An interview with Amit Kedem. Hamakom. https://tinyurl.com/mryaut7s [in Hebrew].

Regev, E. (2017). Patterns of Haredi integration into the labor market: An inter- and multi-sector analysis and comparison. Taub Center. https://tinyurl.com/4bukj28w [in Hebrew].

Regev, E., Crombie, Y., & Susman-Efrati, S. (2021). The future of Beit Shemesh: Mapping the human and employment resources in the city. Haredi Institute for Public Affairs. https://tinyurl.com/2ddcndwk [in Hebrew].

Regev, E., & Gordon, G. (2020). The ultra-Orthodox housing market and the geographical distribution of the ultra-Orthodox population in Israel. Policy study 150. Israel Democracy Institute [in Hebrew].

Research: The case of Lod. (2014). Maoz. https://tinyurl.com/3zzcvb3u

Roibin, E. S. R., & Nurhayati, I. (2021). A model for acculturation dialogue between religion, local wisdom, and power: A strategy to minimize violent behavior in the name of religion in Indonesia. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University, 56(1). https://doi.org/10.35741/issn.0258-2724.56.1.1

Ron, O., Fargeon, B., & Haddad Haj-Yahya, N. (2022). Arab residents of mixed cities: A snapshot. Policy study 178, Israel Democracy Institute [in Hebrew].

Rosen Haberman, A. (2016, November 10). Is Carmiel a mixed city? Tzfon-1. https://tinyurl.com/5yfbu8kt [in Hebrew].

Rosenthal, L., & Levy, S. R. (2010). The colorblind, multicultural, and polycultural ideological approaches to improving intergroup attitudes and relations. Social Issues and Policy Review, 4(1), 215-246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2010.01022.x

Rudmin, F. (2004). Historical notes on the dark side of cross-cultural psychology: Genocide in Tasmania. Peace Research, 36(1), 57-64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23607726

Rudmin, F., Wang, B., & de Castro, J. (2017). Acculturation research critiques and alternative research designs. In S. J. Schwartz & J. Unger (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of acculturation and health (pp. 75-96). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190215217.013.4

Rumbaut, R. G. (2008). Reaping what you sow: Immigration, youth, and reactive ethnicity. Applied development science, 12(2), 108-111. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888690801997341

Sam, D. L., Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Horenczyk, G., & Vedder, P. (2013). Migration and integration. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 221(4), 203-204. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000149

Segal, U. A. (2019). Globalization, migration, and ethnicity. Public health, 172, 135-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.04.011

Senyor, E. (2021, May 12). Preparing for riots in Lod: 10 PM curfew imposed, more than 20 arrested. Ynet. https://tinyurl.com/4ka45zev [in Hebrew].

Sever, M. (2022, December 19). “It feels like the Wild West here”: Unprecedented violence in Beit Shemesh—but youngsters aren’t giving up. Israel Hayom. https://tinyurl.com/3fyxu8dc [in Hebrew].

Sever, R. (2000). And I gathered you from the nations: Processes of aliyah and absorption. In Y. Kopf (Ed.), Pluralism in Israel: From Melting Pot to Salad Bowl (pp. 165-184). Taub Center. https://tinyurl.com/muny5x9r [in Hebrew].

Shaked, L. (2021, April 27), The first public building in the Maof neighborhood will be used a synagogue and a multi-purpose space. Harish24. https://tinyurl.com/mwz4vyn5 [in Hebrew].

Shefferman, K. T. (2008, April 24). Israeli society: a society of migrants. Parliament, 58 Israel Democracy Institute. https://tinyurl.com/99tvzdm [in Hebrew].