Publications

INSS Insight No. 2098, February 9, 2026

The accelerated growth of high-performance computing—particularly for artificial intelligence applications—has driven a sharp increase in electric demand, water consumption for cooling, and land use in dense urban areas. These trends are placing unprecedented pressure on existing data-center infrastructure. Against this backdrop, an innovative approach has emerged in recent years: the deployment of subsea data centers, which leverage the maritime domain as an alternative infrastructure platform, with both environmental and geopolitical implications. This article examines the solution offered by subsea data centers and analyzes the opportunities, risks, challenges, and barriers associated with their implementation.

Modern data centers, especially those dedicated to AI workloads, consume hundreds of megawatts per facility, with a significant share of that energy devoted to cooling rather than computation. Water-based cooling systems have also made the sector a major consumer of freshwater, with daily usage at large AI computing farms comparable to that of a medium-sized city. At the same time, constraints on available land, public opposition to the construction of noisy and heat-intensive facilities in populated areas, and increasingly stringent environmental regulation underscore the need for alternative infrastructure deployment models.

In this context, concerns over digital sovereignty are growing. States and multinational organizations increasingly seek physical control over the location of these infrastructures in order to reduce external dependence and enhance resilience. This consideration further strengthens the case for solutions that combine infrastructural autonomy with environmental sustainability.

The Solution: Subsea Data Centers as a New Model

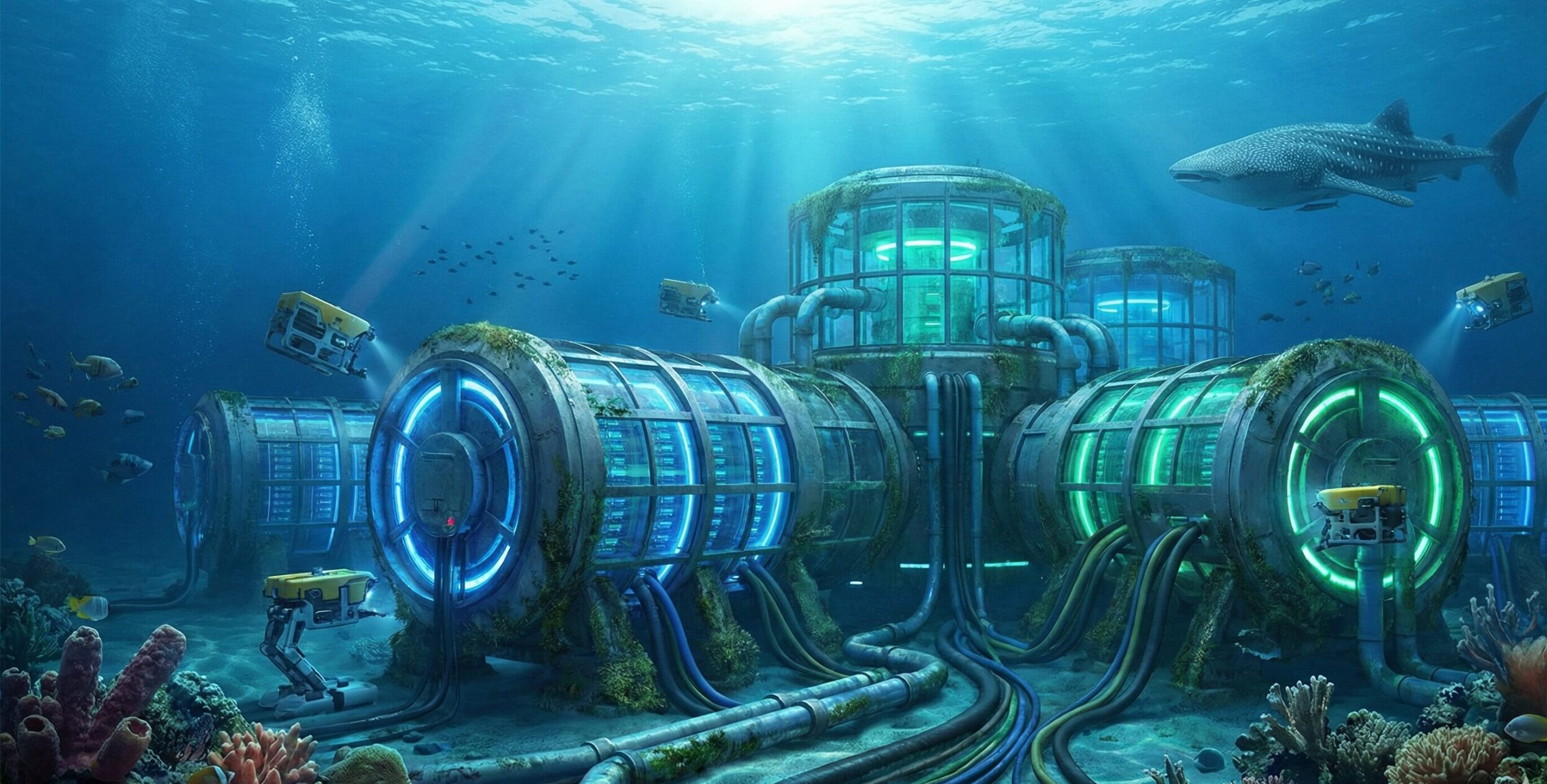

A subsea data center is a computing facility enclosed within a sealed module, deployed on the seabed or anchored at a designated depth, and connected to coastal infrastructure via power and communications cables. The first prominent project in this field was Microsoft’s Project Natick, in which a server capsule was deployed at a depth of approximately 35 meters off the coast of Scotland for about two years. In recent years, China has begun transitioning from experimental systems to commercial-scale deployments, including a subsea data center near Shanghai. This facility integrates energy generation through offshore wind turbines that supply most of the required power, alongside seawater-based cooling designed to save approximately 80% of the energy allocated to cooling in comparable land-based facilities. The project also eliminates the need for freshwater cooling and reduces required land use by roughly 90% compared to terrestrial data centers, while aiming to save about 30% of total energy consumption relative to similar land-based installations. Unlike Microsoft’s research-oriented initiative, this is a flagship Chinese project intended to serve as a cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternative to conventional data centers.

The subsea model addresses four core dimensions:

- Efficient cooling using seawater—direct use of a naturally cool heat sink;

- Freshwater conservation—elimination of reliance on land-based cooling towers;

- Integration with offshore renewable energy—wind, wave, and tidal power;

- Reduced land use—shifting infrastructure into the maritime domain.

As such, subsea data centers constitute an integrated solution—environmental, spatial, and geopolitical—to the challenge of expanding AI infrastructure.

Environmental and Operational Advantages

Energy efficiency and water savings: Data from Microsoft’s project indicate an improvement of approximately 40% in energy-use efficiency, primarily due to the dramatic reduction in cooling energy requirements and the elimination of freshwater use.

Reduced land use onshore: Relocating infrastructure offshore reduces the need to allocate valuable land near population centers, mitigates noise, heat emissions, and visual obstruction, and lowers conflicts with other land uses such as housing, agriculture, and nature reserves. This deployment model helps address public opposition to large-scale cloud infrastructure.

Equipment reliability and lifespan: A sealed subsea environment, characterized by stable temperatures and low oxygen levels, reduces corrosion and electrical failures. Microsoft reported that server failure rates were significantly lower (at least eight times) than in comparable land-based data centers. Lower failure rates translate into fewer hardware replacements, cost savings, and reduced electronic waste.

Geopolitical and Infrastructure Opportunities

The maritime domain, particularly the continental shelf and territorial waters, already serves as a critical infrastructure arena, hosting communications cables, gas and oil pipelines, and more. Integrating subsea data centers into this ecosystem offers several opportunities:

- Digital sovereignty: A state with control over its coastline and territorial waters can establish “maritime AI clusters” that remain physically and legally under national jurisdiction while maintaining proximity to users.

- Energy independence: Co-locating data centers with offshore wind farms enables energy production and consumption at sea, reducing reliance on the onshore power grid.

- Infrastructure resilience: Offshore deployment, away from population centers, may reduce vulnerability to certain threats (such as urban heat stress), although it introduces new categories of risk.

China, for example, is leveraging subsea data centers as part of a broader infrastructure strategy that integrates AI, cloud computing, and green energy, positioning itself to influence emerging global standards in this field.

Environmental, Operational, and Security Risks

Alongside the advantages, subsea deployment entails a range of risks:

Environmental: Researchers and environmental organizations warn about the potential implications of localized water heating, underwater noise, electromagnetic fields, and altered currents. While some pilot projects reported temperature increases of less than one degree Celsius, the cumulative effects of large-scale deployment in sensitive coastal environments remain unclear.

Operational: Installing facilities at depth complicates routine maintenance: Significant failures require raising the module to the surface or deploying specialized underwater vehicles, increasing costs and downtime. In addition, corrosion and hydrostatic pressure necessitate complex engineering and the use of advanced construction materials.

Security and geopolitical: Subsea infrastructure—cables, pipelines, and energy facilities—is already recognized as a target for hostile activity, ranging from espionage to physical sabotage. Subsea data centers add a new layer of sensitivity, as they host critical data and computing power; physical damage could generate systemic effects. Addressing this challenge will require the development of doctrines for protecting subsea infrastructure, enhanced capabilities for subsea domain awareness and control, and improved maritime governance above and below the waterline to prevent both deliberate and accidental damage to critical assets.

Regulatory Challenges and Barriers

Marine environmental regulation: Like other maritime infrastructure, subsea data centers will require environmental impact assessments addressing effects on marine habitats, water temperature, fisheries, and maritime traffic. These assessments are likely to result in complex and lengthy permitting processes.

Law of the sea and sovereignty: The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides a general framework for subsea infrastructure—primarily cables and pipelines—but does not specifically address complex IT facilities. This creates legal gray zones regarding permissible locations within exclusive economic zones, liability for environmental damage, enforcement authority, and the security status of such installations—issues that international and national bodies will soon need to address.

Synergy with existing infrastructure: Ports, offshore wind farms, and existing communications cables could serve as platforms for integrating subsea data centers by providing power connections, access to open waters, and cable routes. Such integration may reduce costs and facilitate permitting if pursued within an integrated maritime spatial planning framework.

Experience from Microsoft’s Project Natick, Chinese initiatives, and regional studies (for example, in the Baltic Sea) indicates that the solution is technically feasible and, in certain dimensions, more efficient than land-based alternatives. However, large-scale implementation will require coordination among multiple stakeholders.

Conclusion

Subsea data centers present an innovative response to the energy, water, and land constraints facing computing infrastructure in the AI era. Their advantages—energy efficiency, freshwater conservation, reduced land use, and integration with renewable energy—are particularly relevant for coastal states seeking digital sovereignty and green infrastructure.

These benefits must be weighed against environmental, operational, and security risks, as well as significant regulatory barriers in maritime and environmental law. Balancing innovation with responsibility will require dedicated regulatory frameworks, in-depth ecological research, and integrated maritime spatial planning.

Even if subsea data centers do not fully replace land-based facilities, they may become an important component of the digital infrastructure ecosystem of coastal states, contributing to a redefinition of the relationship between the maritime domain and the global digital economy.

Israel, as a coastal state with advanced computing infrastructure, should closely examine global developments in this field—particularly given its potential role as an international communications hub due to its location along the east–west axis. Israel’s coastline and sovereign waters already host diverse transmission infrastructure, including communications cables and gas pipelines linking offshore extraction sites to onshore networks. These assets already require updated defense concepts and pose planning, regulatory, and security challenges.

The world is becoming dependent not only on physical “supply chains” transporting goods by sea but also on “information supply chains” and data storage, in which the maritime domain will play a significant role. It is therefore recommended that Israel examine these developments and enable itself, its regional partners in the Middle East, and Israeli stakeholders to participate in this process—drawing on the experience and lessons learned from developing maritime transmission infrastructure that connects Israel to global energy and communications networks.