Publications

INSS Insight No. 1928, December 26, 2024

The success of the rebel forces in Syria in bringing about the fall of Assad’s regime was seen as evidence that China had suffered yet another setback to its policy in the Middle East. Similarly, Israel’s military successes in its war against the pro-Iranian “Axis of Resistance”—Hamas, Hezbollah, and in its confrontation with Iran itself in October—were portrayed as challenges to China’s regional policy. Some commentators argued that the Axis served as an anchor for China to expand its political and diplomatic influence in the Middle East. However, this interpretation misrepresents both China’s strategy in the region and the importance of the Axis of Resistance to China, both in the past and present. The most sensitive issue for China in Syria remains the Uyghur rebels, but its overall policy in the region is expected to continue as it was before the developments in Syria.

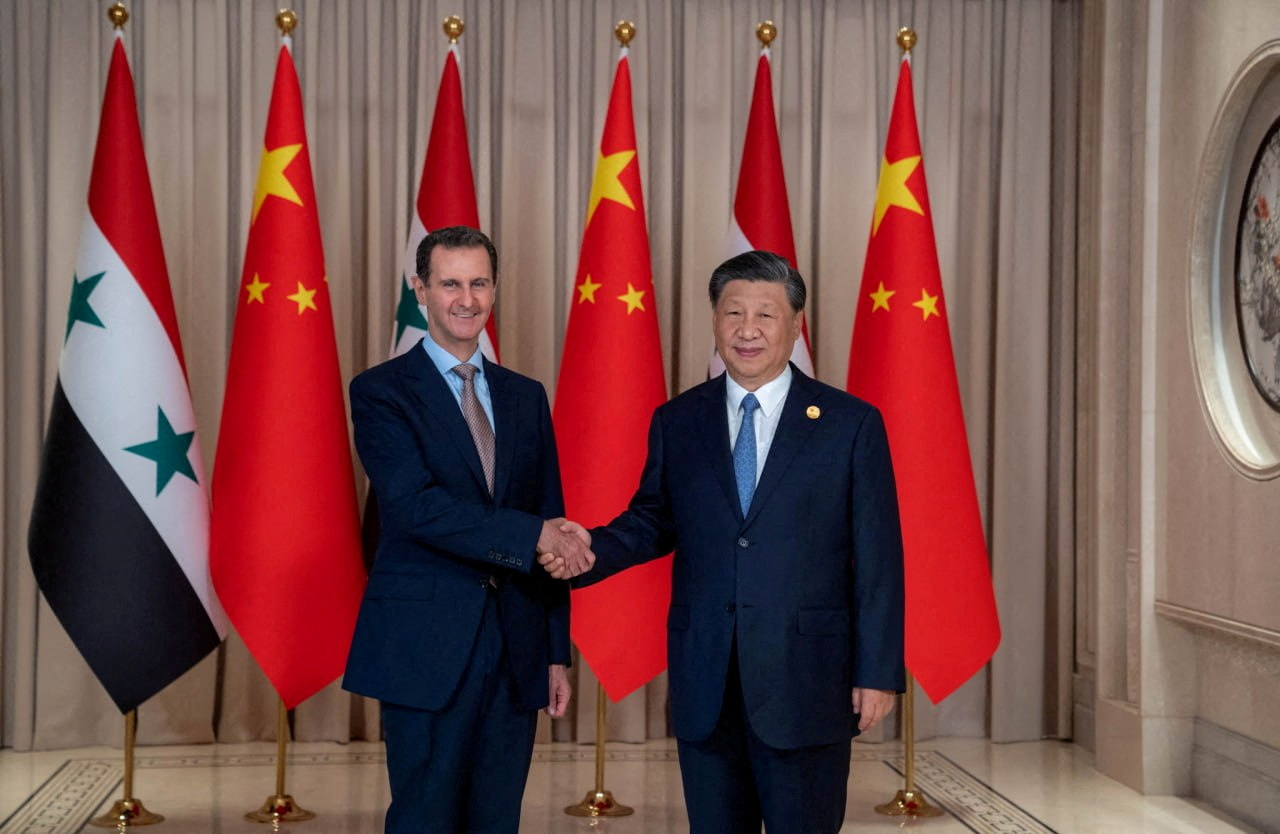

Despite the strengthening of the “Axis of Resistance” over the past decade, China has been cautious about moving closer to Syria. Speculations about substantial Chinese involvement in Syria’s reconstruction efforts, which have repeatedly been heard since the mid-2010s, have consistently been proven baseless. In the past two years, as Syria began to reintegrate into the Arab world, Sino-Syrian relations appeared to improve. In early 2022, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding on Syria’s entry into China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); and in September 2023, during Bashar al-Assad’s visit to China, the Syrian and Chinese presidents announced a “strategic partnership” between their countries. Media headlines once again speculated about the extent of Chinese aid planned for Syria’s reconstruction, especially given the many discussions held between the two countries on economic cooperation. However, in practice, such aid has largely failed to materialize.

The decline in trade volume between China and Syria in 2023—and the consistent downward trend in trade between the two countries over the years, with almost no significant business agreements—has generally escaped media attention. Since 2011, China has used its veto power in the UN Security Council to block resolutions against Syria and has repeatedly called for lifting sanctions on Syria. However, these declarations of support, Syria’s entry into the BRI, and even the strategic partnership between the two countries have had little tangible impact. China’s declarations of support continued even on the eve of the rebel offensive. On November 21, 2024, China’s representative to the UN Security Council reiterated key positions, calling for the withdrawal of foreign forces from Syria—implying American forces, not Russian and Iranian forces—and again demanding the immediate removal of sanctions. The Chinese representative also condemned Israel’s airstrikes in Syria, a stance that China has repeatedly taken.

China was not alone in failing to anticipate the Syrian rebels’ success, sharing this misjudgment with many others. However, in the initial days of the offensive, China maintained its previous position. China’s understanding of the region has remained significantly flawed. Even after the rebels had achieved considerable successes, China’s representative, Fu Cong, upheld the same line during a Security Council discussion on December 3, 2024. Fu expressed China’s support for Syria’s efforts to combat terrorism and maintain national stability and security, referring to the rebels as terrorist forces. He also condemned the rebels’ takeover of the Iranian consulate in Aleppo, encouraged various countries to cut off the supply lines to the rebels, and called for the removal of sanctions on Syria while condemning foreign forces in Syria.

However, in the days that followed, China refrained from making significant statements on the matter, appearing to grapple with the events unfolding in the region, perhaps without much success. While Russia and Iran demonstrated their presence (diplomatically at least) on the ground, with Assad visiting Russia and Iran’s defense minister traveling to Damascus, China remained on the sidelines. In early December, China’s Deputy Prime Minister Zhang Guoqing visited Iran on a mission officially described as aimed at improving economic relations between China and Iran, with no public mention of Syria. After the rebels captured Damascus, China’s initial response was brief, focusing on the safety of Chinese citizens in Syria. A few hours later, China added that it hoped the fragile and dangerous situation in Syria would stabilize soon.

This approach does not rule out the possibility that China will engage with Syria once stability is restored and the threat of renewed civil war subsides, and once China believes this is a long-term development. Business is business, and China would willingly cooperate with any party that serves its interests—even those it previously labeled as “terrorists.” President-elect Donald Trump’s statements about how “China can help,” although made in the context of Ukraine, could be relevant for Syria in the future, and in the broader region, including Iran, even sooner.

China’s primary concern regarding Syria is not its strategic importance (which is minimal at this stage) nor the weakening of the “Axis of Resistance” (this development in itself does not truly harm China). Rather, China’s concern lies in the presence of Uyghurs among the rebels, particularly in the “Turkistan Islamic Party” (TIP). China, and others, classify this group as a radical terrorist organization that poses a direct threat to China. If TIP gains influence in Syria’s governance or spreads its ideology beyond Syria to neighboring regions such as Pakistan and Afghanistan along China’s border—or within China itself—Beijing will face challenges in future collaboration with Damascus even if stability is restored. TIP’s repeated statements regarding China, including calls to “liberate East Turkestan” (as they call Xinjiang), further heighten China’s concerns. This issue extends beyond Syria to other regions where TIP operates, especially Afghanistan, and could affect China’s future relations with Syria.

This issue also has potential implications for Sino-Turkish relations, although any impact is likely to be minor. Until around 2015, Turkey inconsistently supported the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, even criticizing China on the matter. However, as Turkey’s relations with the West deteriorated and its economy weakened, Ankara increasingly relied on Beijing, pushing the Uyghur issue to the sidelines and even suppressing related domestic protests. Turkey, of course, did not support the Syrian rebels because of the small Uyghur minority among them, and it is likely that Turkey will continue to downplay the Uyghur issue to preserve its economic ties with China. Moreover, Turkey’s aspirations to position itself as a hub for supply chains (including energy) from China to Europe depend on both regional stability and strong relations with China—which are also Chinese interests.

Nevertheless, China’s overall approach to the Middle East and its key relationships in the region remain unchanged. China’s “global initiatives”—particularly the Global Security Initiative (GSI) and the Global Development Initiative (GDI)—were launched before its China boasted its role in facilitating reconciliation between Saudi Arabia and Iran in March 2023, and China continues to prioritize these initiatives, as well as the BRI, focusing on economic and technological involvement, especially in energy. The Gulf states and Egypt remain the primary countries for advancing these interests, alongside friendly declarations toward Iran. Syria and the “Axis of Resistance” have not played a significant role in these matters.

China’s policy in the Middle East remains opportunistic. It will continue to project itself as a state with political weight (to advance settlements) in the region, even if its actual influence remains limited. Beijing continues to emphasize that the region’s countries should determine their own futures, urging the international community to support and encourage this, while hinting or explicitly stating that “foreign intervention” (i.e., American) is a problem that only exacerbates instability. This rhetoric aligns with China’s broader strategy toward the “Global South.” Foreign Minister Wang Yi reiterated this approach during his meeting with Egypt’s foreign minister on December 13 and his meeting with Arab ambassadors on December 19. In fact, the weakening of the “Axis of Resistance,” particularly Iran, could even strengthen China’s leverage over Iran. Should nuclear negotiations resume against the backdrop of a credible military option—and if President-elect Trump decides that “China can help,” similar to his comments about Ukraine—China could find itself with greater influence in the region.

China continues to declare its support for the Palestinians and Arab/Muslim states while criticizing Israel’s airstrikes in Syria and its actions in the Golan Heights buffer zone. Israel’s successes do not undermine China’s policies, as Beijing has consistently positioned itself as a supporter of all Arab and Muslim states, rather than exclusively backing the “Axis of Resistance.” Syria has never been a central factor in China’s Middle East policy, and China’s policy toward Israel is unlikely to change significantly as a result of these events. However, ceasefires could shift Beijing’s perspective—not necessarily in terms of official policy statements but by creating opportunities to foster stronger ties between China and Israel through practical collaboration on the ground.