Strategic Assessment

Introduction

The Israel–Hamas War, that began with Hamas’ attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, focused attention on numerous issues that have long been the subject of public and political controversy in Israel. Among other things, it intensified the debate surrounding the conscription of the ultra-Orthodox population to the IDF, which in essence focuses on the granting of exemptions from military service to yeshiva students who devote their lives to Torah study, in a state whose greatest expression of mutual responsibility is participation in the military.

Several factors contributed to this development. Foremost among them is the assessment that the central lesson of the war is the need for far-reaching, transformative changes in the defense establishment in general, and in the Israel Defense Forces in particular. “[After] Hamas’ attack on October 7, 2023,” writes Major General Yaniv Asor, “the surprise and shock experienced by the IDF and Israeli society, the expansion of the campaign across multiple arenas, and its prolonged duration, compel us to undertake a fundamental reorganization and to mobilize efficiently and urgently in the face of the threat confronting us” (Asor, 2025, p. 4).

One of the central lessons of the war—one that appears to command a broad consensus—is the need to abandon the paradigm that has accompanied the IDF over recent decades that Israel can defend itself with a small army. “The idea of a ‘small and smart army,’” writes Major General Asor, “is another clear manifestation of the [mistaken] manpower conceptzia [governing assumption] … [which] underpinned the notion of a ‘select serving elite’” that can ensure the safety of Israel (Asor, 2025, p. 4).

Major General Asor concluded his remarks by stating what is now clear to all, that:

It was indeed correct until the outbreak of the present war, to conduct ourselves with a consciousness that we are a “mobilized nation.” Namely, that we can maintain just a small army. However, the scope of the present war, its duration, its lessons, and the security challenges that lie ahead, require us to maintain a large, smart, trained, equipped, and properly budgeted army […] The protracted war and the understanding that we are facing a decade that will demand sustained security challenges oblige us to formulate a manpower strategy that is commensurate with the needs of attrition and fatigue that are always part of long wars, and that provides us with strategic depth, resilience, and a permanent force (Asor, 2025, pp. 4–5).

This article is written against the backdrop of the intensifying debate in Israeli society over the conscription of ultra-Orthodox men and yeshiva students into the Israel Defense Forces. Its purpose is to present the historical background related to the exemption from military service granted to the ultra-Orthodox and to yeshiva students in the early years following the establishment of the state. The analysis is based primarily on historical documents that were collected for this study from the State Archives and the Ben-Gurion Archive.

The basis for this article is the 1988 report of the Subcommittee of the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee for the Re-examination of the Exemption from Conscription of Yeshiva Students (the Cohen Committee). The overwhelming majority of the committee’s members, chaired by Member of Knesset Menachem Cohen, supported the conscription of yeshiva students into the IDF, on the basis of a variety of proposed frameworks.

The committee undertook a thorough examination in its efforts to understand the roots of the arrangement that had led to the entrenchment of the existing situation regarding the non-conscription of yeshiva students into the IDF since the establishment of the state. However, the clearly imbalanced composition of the committee ultimately ensured that its conclusions would not be accepted by the religious parties or by the leaders of the ultra-Orthodox yeshivas.

Ultimately, the committee failed to fully grasp the nature of its objectives. It was not expected to function as an academic research body, but rather as a politically oriented committee. Eventually, its ultimate test lay in the formulation of solutions that could be implemented within the existing constraints of Israeli society.

The arrangement granting an exemption to yeshiva students was established during the War of Independence by David Ben-Gurion. One may, of course—and with good reason—question this decision and the degree of prudence it entailed. In practice, however, it created a powerful political fait accompli. The nature of Israel’s political system and the procedures governing the formation of coalitions and governments in Israel (along with other factors) require, in the view of this author, the relevant actors to proceed with wisdom and sensitivity in order to advance an arrangement that is acceptable to the majority of the parties concerned, if not to all of them.

The choice of the Cohen Committee as an anchor for this study is intended to convey a message to all those who rightly seek to change the reality that was entrenched during the War of Independence and has remained in place ever since. Such change can be realized only on the basis of broad consensus within Israel’s political system and public sphere.

The Cohen Committee on the Conscription of Yeshiva Students

On July 9, 1986, the Knesset plenum decided to refer to the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee a motion for the agenda submitted by Member of Knesset Geula Cohen on “the need to act against draft evaders from non-Zionist yeshivas.” In an impassioned speech, MK Cohen expressed her deepest convictions about the exemption granted to yeshiva students from service in the IDF. “What is at issue here,” she stated, “is not merely moral distortions relating to quality of life, but moral distortions that touch upon life itself—matters of life and death” (224th Session, 1986, p. 3491).

At that same session, Geula Cohen noted that the number of yeshiva students receiving exemptions from service in the IDF was steadily increasing. In 1981, she stated, 700 students had requested exemptions; by 1986, that number had doubled. What, she asked, explained this doubling? She claimed that some of those seeking exemptions were young men attempting to evade military service. All of them, she argued, were granted repeated deferments from military service until they passed the age of conscription, and thus never served in the IDF at all.

The Minister of Defense at the time, Yitzhak Rabin, did not dispute her remarks. However, his message was that, in practice, political constraints necessitated the continuation of the existing arrangement. “The question of the scope of the conscription of yeshiva students, in all its aspects” he stated, “has been considered on numerous occasions in the past by Israeli governments of every period, and there is nothing new in this motion for the Knesset agenda that would justify a change in policy” (224th Session, 1986, p. 3493).

Many years later, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (may his memory be a blessing) leveled sharp criticism at Geula Cohen for her efforts to promote the conscription of yeshiva students: “She stands at the forefront of those [who claim] that yeshiva students must be conscripted—this wicked woman; what religion has she ever had?” (Gottlieb, 2022).

On December 23, 1986, the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee held a session to discuss Geula Cohen’s July 9 proposal. Following the deliberations, the committee decided to establish a subcommittee under its auspices to re-examine yeshiva students’ exemption from conscription. The subcommittee was composed of Members of Knesset Menachem Cohen (chair); Binyamin Ben-Eliezer; Sarah Doron; Rabbi Haim Druckman; Micha Harish; Rafael Pinhasi; and Yossi Sarid.

On July 18, 1988, the committee published its report, including the executive summary and its conclusions and recommendations, which were adopted by a vote of four in favor, one opposed, one abstention, and one absent. The committee should have been aware that it was addressing an issue of exceptional complexity, sensitivity, and political volatility. For this reason, heightened sensitivity and political prudence were required in determining the committee’s composition. It was necessary to ensure appropriate representation of viewpoints opposed to those of the majority of its members.

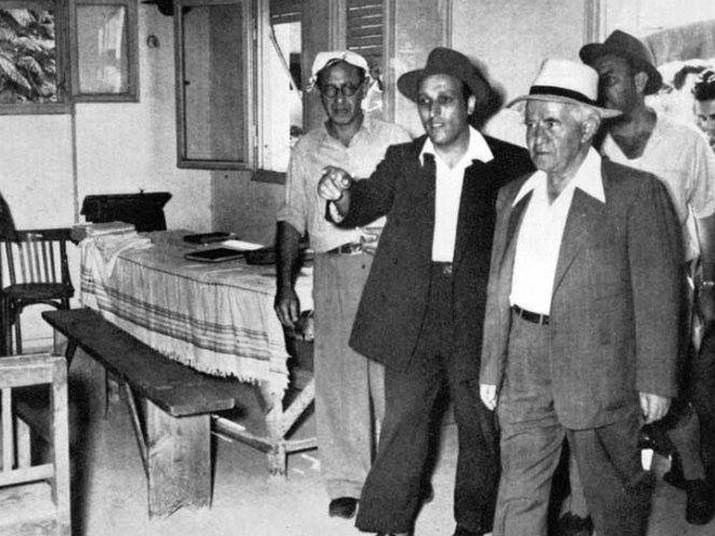

The committee was fully aware of the claim that Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, was the one who laid the foundations for granting yeshiva students an exemption from conscription into the IDF. However, it emphasized that “Ben-Gurion’s intention was to exempt only a limited number of yeshiva students—several hundred at most, not thousands—as the situation evolved over the years.”

This assessment, the committee members determined, is also corroborated by Ben-Gurion’s remarks at a meeting of the Security Committee of the Provisional State Council on October 1, 1948, where he noted that the rabbis had argued that “there are 400 yeshiva students, all of them young, and that if they were obligated to enlist, the yeshivas would have to be closed” (Re-examination of the exemption from conscription of yeshiva students, 1986–1988, p. 8; Security Committee of the Provisional State Council, 1948).

Ben-Gurion himself lent support to this argument in the years following his resignation from the government. “I exempted yeshiva students from military service,” he wrote to Prime Minister Levi Eshkol on September 12, 1963. “I did so when their numbers were small, but their number is steadily increasing […] In general, it may be necessary to reexamine the entire question of whether yeshiva students should be exempt from military service” (Ben-Gurion, 1963).

These later claims by Ben-Gurion—that the exemption was granted to only a limited number of yeshiva students, and that with the growth of the ultra-Orthodox population in Israel it is difficult to justify the continuation of the arrangement—appear somewhat puzzling. Was Ben-Gurion unaware that the ultra-Orthodox population tends toward a high rate of natural increase? Was he unaware of the fact that religious parties would always be crucial for the establishment of any coalition in Israel?

Moreover, the Cohen Committee emphasizes in its report that it is quite likely that Ben-Gurion himself understood that the decision to grant the exemption was actually flawed from the outset. Accordingly, he sought to lend it a more “universal” character. Thus, at a meeting of the Security Committee, he stated that the policy of the government and the Ministry of Defense was to refrain from closing any institution of higher or secondary education because of the war, insofar as this was possible. “We promised the high schools that the twelfth grade would not be closed, even though the twelfth-grade students—the male students—are being conscripted, but not the female students. We promised the university to make arrangements so that it would remain open even during wartime. Our policy is not to close educational institutions, just as our policy is not to close factories. We are concerned to ensure that the university, the Technion, and the upper grades of the secondary schools remain open” (Security Committee of the Provisional State Council, 1948).

The chairman of the Cohen Committee, Rabbi Menachem Cohen, was a Member of Knesset who had served as the rabbi of the Moshavim Movement (representing cooperative agricultural villages) and as a Knesset member on behalf of the Labor Party. His sympathies clearly lay with supporters of the conscription of yeshiva students, though he was prepared to accept certain compromises on the issue: “The basic principle that I proposed, and that was accepted by the majority of the committee’s members, was to limit the number of those receiving exemptions from compulsory service not by a numerical quota, but rather according to the academic level of the students […] The arrangement for the conscription of yeshiva students would apply only to students of recognized yeshivas and religious secondary schools” (Huberman, 2025).

In addition, the committee recommended the establishment of a framework akin to an academic reserve track for yeshiva graduates. Under this arrangement, each yeshiva student—provided that the yeshiva was officially recognized—would be permitted to study from age 18 until age 24. At the conclusion of this period, the students would take examinations, and only two hundred outstanding students each year would receive a full exemption from security service and be allowed to continue their studies. The remaining students, the committee recommended, would be conscripted for a shortened period of service lasting one year, after which they would be assigned to the IDF reserve system and serve in coordination with the heads of the yeshivas.

However, the committee claimed, once the right-wing parties won the election of 1977, the floodgates were opened. Much larger number of yeshiva students were exempted from military service than ever before. As the committee stated in its concluding remarks:

In 1977, the non-service of yeshiva students significantly increased, and became a focal point of controversy and a source of tension within Israeli society. There is no dispute regarding the central role of the State of Israel in encouraging the growth and development of yeshivas in their various forms. Under these circumstances, many question the existing arrangement, whose origins date back to the establishment of the state. A historical and moral sensitivity to ensuring the continuity of Torah study among the Jewish people led the state’s leadership, under David Ben-Gurion, to institute the existing framework. However, its continued existence in the present day reflects an alienation of growing segments within Israeli society who perceive themselves as exempt from bearing the security burden necessary for the State of Israel’s survival.

To the committee’s credit, it should be stressed that it presented important documentation of the deliberations and positions of senior figures in the state’s leadership during the early stages of statehood with regard to this complex and contentious issue. The committee’s report enables us, even from the vantage point of many years later, to gain a clearer understanding of the considerations for and against granting an exemption to yeshiva students.

Historical Overview

The process leading to the arrangement granting yeshiva students an exemption from service in the IDF began even prior to the establishment of the state. Its origins lie, inter alia, in Ben-Gurion’s desire to form as broad a coalition as possible of political forces in support of the Partition Plan. One of the most prominent expressions of this effort was the well-known Status Quo Letter of June 19, 1947, addressed to the leaders of Agudat Israel, in response to their demands for guarantees concerning various religious issues in Israel. (Ben-Gurion, 1947).

With regard to matters of personal status (marriage and divorce), Ben-Gurion stipulated that the situation that had prevailed during the Mandate period would be maintained. Namely, these issues would be adjudicated by the religious courts of each community; the Sabbath would be observed as “the legal day of rest of the State of Israel,” in accordance with Jewish tradition; and kashrut would be maintained in state institutions in accordance with Orthodox halakha (Friedman, 2018). From Ben-Gurion’s remarks it may be inferred that the State of Israel was not intended to be a theocratic state. Freedom of conscience would be guaranteed to all.

During the siege of Jerusalem, the “Central Command in service of the people” (a command-administrative body responsible for mobilizing manpower for the campaign) required all men between the ages of 17 and 55 to enlist in the defensive forces. The manpower shortage was acute. Against this backdrop, an understanding was reached between the Chief Rabbis and representatives of the Haganah, according to which yeshiva students aged 17 to 22 would undergo training within a special framework suited to the distinctive environment in which they had been educated. (Otzar HaTorah, 5782 [2021/22]; on the Central Command, see Tamari, 2012).

On January 27, 1948, Chief Rabbi Isaac Herzog published a wide-ranging article on the issue of conscripting yeshiva students in view of the approaching war. The article treads a careful path. On the one hand, it calls for the full mobilization of all those obligated to enlist in the fateful campaign; on the other, it demands the preservation of the “world of Torah” that had been destroyed in the Holocaust.

For the most part, this was a halakhic study grounded in a wide range of sources. The rabbi makes clear that the Jewish community was facing danger of annihilation, and that the war looming ahead was a milhemet mitzvah (an obligatory war). In such a war, according to the Jewish law, “all go out [to fight], even a bridegroom from his chamber and a bride from her canopy” (Conscription of yeshiva students, n.d., p. 3). Where even a bridegroom and bride are obligated, the rabbi argued, a fortiori Torah scholars are likewise obligated. In his view, even the greatest sages of Israel are not exempt from participation in a milhemet mitzvah.

“In a time of danger,” he stated, “[we must] impose upon yeshiva students a duty of guard service within the city […] we are facing an immediate threat of siege and must mobilize every bit of manpower at our disposal” (Conscription of yeshiva students, n.d., pp. 1–2). Later in his remarks, the rabbi wrote:

At the same time, great care must be taken not to cause—Heaven forbid—the disruption or undermining of Torah study, even for a short period. This applies especially in our present circumstances, when the centers of Torah in the Diaspora have been destroyed. We have to know we have no guardian but the Torah and the yeshiva students […] The commanders understand this and seek to avoid measures that would lead—Heaven forbid—to the suspension of the yeshivas, even temporarily. Therefore, in my view, the heads of the yeshivas should reach an appropriate arrangement with them regarding partial conscription under certain conditions (Conscription of yeshiva students, n.d., p. 46)

Rabbi Herzog rejected the claims of those demanding exemptions on the grounds that non-Jewish states, too, had exempted religious scholars from military service. First, he argued, during the Second World War even religious students were conscripted into the British Army. Beyond that, he maintained, the Jewish community in Israel was living in a unique historical moment, one that required exceptional considerations adapted to the nature of the threats it faced.

At the same time, the rabbi held that the state should recognize the special status of outstanding Torah scholars who devote their lives to Torah study, much as the Torah itself recognized the unique status of the Tribe of Levi and exempted them from military service. In his view, they constitute an existential necessity for the nation no less than the army or the police. Without Torah and halakhic adjudication, he concluded, the State of Israel could not endure as a Jewish state.

On February 12, 1948, the Central Command in Service of the People issued a proclamation clarifying that it acknowledged and appreciated the arguments advanced by the heads of the yeshivas in justification of postponing the conscription of yeshiva students, despite full awareness of the gravity of the situation. Nevertheless, the Command maintained that the obligation to undergo training for self-defense applied to every young Jew. (Central command in service of the people, 1948).

It was therefore deemed desirable that all yeshiva students, like all other young men in Jerusalem, undergo training in self-defense, on the assumption that they would not be deployed operationally except in cases of necessity and pikuach nefesh (the preservation of life). If, for various reasons, this arrangement was not acceptable to the heads of the yeshivas, the Command agreed that a yeshiva student would be issued a deferment certificate for three months, at the end of which the matter would be reconsidered in light of prevailing circumstances. Such certificates would be granted only to yeshiva students for whom Torah study constituted their full-time vocation (Central command in service of the people, 1948).

In practice, the proclamation amounted to full acceptance of the position of the yeshiva heads and left the option of defensive training to the goodwill of the yeshiva students themselves.

On March 9, 1948, the Rama—Head of the National Headquarters, Israel Galili—issued his decision to exempt yeshiva students from security service. This decision, it was stipulated, would remain in force for the year (1948), at the end of which the issue would be reconsidered. The exemption was granted subject to a minor reservation, stating that “students who are capable will be given training in self-defense at their place of study […] in such a manner that the academic routine of the yeshivas will not be disrupted” (Schlesinger, 2014). In practice, however, this directive was not implemented. The heads of the yeshivas sought to have this decision anchored in law, but Ben-Gurion opposed such a move.

This very “generous” position of the defense establishment was also reflected in reports on Rabbi Herzog’s meetings with security officials in the country. These officials, it was reported, demonstrated deep understanding regarding the issue of conscripting yeshiva students into military service. Already at the first meeting, the head of the Jerusalem Recruitment Office, Mr. Yaakov Tchernowitz (Yaakov Tzur, who would later serve as Israel’s ambassador to France), declared that it was certainly not the intention of the security forces to close the halls of Torah study or to compel their students to undergo full conscription in accordance with the general mobilization order that had been issued.

However, the granting of a sweeping exemption to yeshiva students is difficult to comprehend. It was issued at a time when the IDF was suffering from a severe manpower shortage. It was facing profound uncertainty regarding the Yishuv’s ability to withstand the heavy campaign waged by the Arab armies. Indeed, a very real danger of annihilation loomed over the Jewish community in the country. Galili himself made this clear at a meeting on April 26, 1948. A confrontation with the Arab Legion, he warned, was drawing near and in anticipation of these impending challenges, the Yishuv lacked the necessary forces to defend itself.

However, it appears that even this arrangement did not function smoothly. In early May 1948, Rabbi Herzog received reports that personnel of the Central Command were withholding food from yeshiva students who refused to perform guard duty. The rabbi reacted with fury to this action: “If you punish those yeshiva students,” he warned, “brand them as mere draft evaders and cut off their food, whatever your justifications may be, I will rise against you in open and fierce protest before all Israel. You have no authority to employ such drastic coercive measures against the remnant of the survivors who uphold our holy Torah in Jerusalem, our holy city. From them, as you certainly know, Torah will go forth to the Land of Israel and to all Israel” (Herzog, 1948).

Ben-Gurion’s willingness to accommodate the religious establishment even during the difficult period of the War of Independence found expression at a meeting of the Provisional State Council on June 17, 1948, during which Rabbi Menachem Mendel Hager raised the issue of the shortage of tallitot and tefillin for soldiers fighting in the war:

There are thousands of soldiers who come to us day after day requesting tallitot and tefillin […] It may be that a sense of religiosity is awakened with greater force when a person goes out to the front. Is it acceptable to you that a religious soldier should come and ask for charity […] for a tallit and tefillin? The fact is that people come to the hevra kadisha (a Jewish community organization responsible for preparing the deceased for burial according to Jewish law) to request tallitot belonging to the deceased […] I am certain and convinced that if the Minister of Defense were to request a special budget for this purpose, the Minister of Finance would surely not refuse. This is a very serious matter, which in my view demeans the dignity of the religious soldier in our army. Provision must be made so that we are not forced to distribute tallitot of the deceased to soldiers who request them, but rather that these be provided with dignity by the government. (4th Session of the Provisional State Council, 1948, p. 28).

Ben-Gurion heard these remarks and immediately responded: “This is the first time I have heard about the matter of tallitot and tefillin. I can assure you that every soldier who needs tallit and tefillin will receive them. He is entitled to this, and a budget will be found for it, just as there is a budget for other things” (4th Session of the Provisional State Council, 1948, p. 28). It is quite likely that this gesture was intended, inter alia, to signal to the “guardians of the Torah” that the defense establishment would attend to their religious needs should they consent to enlist in the IDF.

The decision to grant yeshiva students an exemption from conscription aroused perplexity among members of the leadership. Some claimed that ultra-Orthodox youths were rushing to enroll in yeshivas as a result. One of them, a member of the Security Committee of the Provisional State Council and later chair of the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, Meir Grabovski (later Meir Argov), asked at a meeting of the Security Committee on September 17, 1948: “Is it true that all yeshiva students in the country are exempt from conscription, and that on this basis the yeshivas are currently full of students?” (Security Committee of the Provisional State Council, 1948).

Already toward the end of 1948, Ben-Gurion expressed his dissatisfaction with the conduct of the rabbinical establishment on matters of religion and state. For example, he questioned the need for two chief rabbis at a time when the state was facing severe financial distress. Nevertheless, in the final analysis he continued to support an accommodating approach toward the religious establishment in matters of religion–state relations, and, of course, also on the issue of military conscription: “These dividing lines [between religious and secular communities in Israel] will not be easily dismantled. The state must provide for the religious needs of its citizens and refrain from coercion. If some Jews say they will go their own way, they should be allowed to do so, even though it would be preferable that there not be so many divisions among the Jews” (Minutes of the provisional state council, 1948, p. 32).

It is quite likely that Ben-Gurion had in mind the views of Rabbi Abraham Isaac HaCohen Kook (the Ra’ayah) regarding the conscription of yeshiva students. Ben-Gurion held him in great esteem. “The success of the state in its wars against its enemies,” Rabbi Kook argued, “depends on the presence within it of Torah scholars engaged in study. They benefit the state more than the fighting soldiers themselves.” According to Jewish law, Torah scholars must not be pressured to go out to war. (Nagari, 2024).[1]

It appears that Ben-Gurion was also aware of opposing views to that mentioned above. One such view was articulated by Rabbi S. Y. (Shlomo Yosef) Zevin in an article published in 1948, which he signed simply as “one of the rabbis.” In a tone of defiance and criticism directed at rabbis who demanded an exemption from conscription for yeshiva students, he asserted that such a position had no halakhic basis whatsoever. The saving of even a single Jewish life—let alone many lives—is a fundamental principle of Jewish law: “The Torah’s view? It is simple and clear: ‘He who hastens [to save lives] is praiseworthy, and there is no need to seek permission from a rabbinical court!’” (Zevin, 1948, p. 373). Ben-Gurion chose to disregard this opinion at that time.

The deliberations surrounding the exemption from conscription continued into 1949. In that year, then Minister of Defense, David Ben-Gurion, informed the Minister of Welfare, Rabbi Y. M. Levin (the first Minister of Welfare of the State of Israel until 1952 and a prominent leader of Agudat Israel), that he had agreed to defer the conscription of yeshiva students for whom Torah study constituted their full-time vocation. This deferment was based on Section 12 of the Defense Service Law, which authorizes the Minister of Defense to exempt an individual from military service on educational grounds (Knesset Research and Information Center, 2018, p. 2). As Ben-Gurion himself stated in the Knesset plenum in March 1953: “The law permits the exemption of individuals from the army on grounds of education, economy, family, and health. On this basis, yeshiva students were exempted” (201st Session, 1953, p. 875).

On July 18, 1949, a meeting was held between Ben-Gurion and Rabbis Isaac Herzog and Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel (who had served as rabbi of Jaffa and Tel Aviv, rabbi of Salonika, and later as the Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem). The rabbis briefly raised the need to grant yeshiva students an exemption from conscription into the IDF. Ben-Gurion avoided giving a definitive response, making it clear that it was still too early to address the issue. From the somewhat evasive wording of Ben-Gurion’s remarks, it may be inferred that even at this stage he harbored doubts as to whether the sweeping exemption he had granted to yeshiva students during the war had been justified (Ben-Gurion, 1949a).

On January 28, 1949, Rabbi Herzog sent Ben-Gurion another letter on this issue. In his first remarks he described,

…the terrible Holocaust, in which tens of thousands of yeshiva students in Europe—their leaders and sages, of blessed memory—were destroyed, and from whom only a small remnant remains.

Under these circumstances, he stressed,

…it is my opinion that they [the yeshiva students] should be exempted from military service in order to allow these few to continue the study of our holy Torah, which is also a necessity and an honor for our state (Knesset Research and Information Center, 2007, p. 7).

In his reply to Rabbi Herzog, Ben-Gurion expressed considerable reservations regarding the phenomenon of granting exemptions. He did not respond negatively to the request outright. However, given the Chief Rabbi’s esteemed and respected standing, Ben-Gurion’s statement that he would forward the request to the Chief of Staff for consideration can reasonably be interpreted as a courteous rejection. According to Ben-Gurion, while he appreciated the reasoning behind the request to exempt yeshiva students from military service, there was concern that this right might be misused. There had already been instances confirming such concerns. He therefore stated that he would ask the Chief of Staff to examine Rabbi Herzog’s request with the appropriate degree of care.

Several months after the conclusion of the War of Independence, Ben-Gurion again expressed his view that the sweeping exemption warranted re-examination. On December 27, 1949, he met with Minister Moshe Shapira, later a leader of the National Religious Party. The minister, Ben-Gurion noted, came to demand the exemption of yeshiva students from conscription. Ben-Gurion replied that he had already given such an assurance, but at the same time expressed his desire to meet with the heads of the yeshivas in order to explain to them that “they are doing something that is not good.” The implication of this phrasing is that, formally, Ben-Gurion still adhered to the approval he had granted. Nevertheless, he expected the yeshiva leadership itself to initiate a dialogue aimed at changing the existing arrangement in a manner that would lead to the integration—at least in part—of yeshiva students into the war effort (Ben-Gurion, 1949b).

At a meeting with Minister Rabbi Yitzhak Meir Levin on January 8, 1950, the prime minister informed him that he had already issued instructions not to apply the Defense Service Law to yeshiva students. At the same time, Ben-Gurion indicated his desire to meet with the heads of the yeshivas in order to persuade them to permit at least basic training for yeshiva students, so that they would be able to bear arms when the need arose. Minister Levin expressed reservations about this proposal, arguing that it lacked practical significance, since it concerned only several hundred yeshiva students (Meeting between Ben-Gurion and Minister Levin, 1950).

Ben-Gurion found it difficult—justifiably so—to accept this position. He argued that in a wartime situation even several hundred yeshiva students trained in combat could be of significance. He made it clear that he would attempt to persuade the heads of the yeshivas to agree to such an arrangement, but that if they refused, he would not act contrary to their wishes. He further clarified that young rabbis serving in active rabbinical positions would also be exempted from military service (Meeting between Ben-Gurion and Minister Levin, 1950).

From a secular perspective, it is difficult to understand the motives that led Rabbi Levin to oppose a move that ostensibly would also have benefited the yeshiva student population. Such an arrangement would have enabled them to demonstrate at least a degree of participation in the war effort without undermining the Torah study to which they were expected to devote themselves day and night. Moreover, under the security circumstances that threatened the lives of all members of the Yishuv, it was of considerable importance that every citizen be capable of bearing arms and knowing how to use them.

Minister Levin’s position can be understood only against the backdrop of the deep suspicion that prevailed within the ultra-Orthodox public toward the secular establishment. The prevailing assessment was that the security establishment would exploit any opening in order to bring about the conscription of yeshiva students. Levin and his associates most likely feared that severe security circumstances might arise that would necessitate the immediate mobilization of yeshiva students, on the assumption that they could contribute in some measure to strengthening the sense of security. It is quite plausible that Levin’s concern was that any degree of integration into the security system would become an irreversible fait accompli.

It is even more difficult to comprehend the ease with which Ben-Gurion was prepared to relinquish a demand that was so justified, so symbolic, and so significant—both for yeshiva students and for the State of Israel. The man who knew how to wield power forcefully, resolutely, and even ruthlessly against his political rivals is behaving here as strikingly restrained and lacking in determination. The leader who dismissed Galili from his position as head of the National Headquarters, who dismantled the Palmach headquarters, and who ordered the sinking of the Altalena with full awareness that it would have lethal consequences, appears here in an entirely different and markedly softer light.

The puzzle deepens in light of Ben-Gurion’s pronounced estrangement from the world of religious observance and from the meticulous adherence to every halakhic detail that characterized ultra-Orthodox Judaism. Ben-Gurion loved and revered the Bible—the valor of the patriarchs and the prophets who arose among the people of Israel—but he clearly did not identify with rabbinic Judaism, with which he was negotiating over the exemption of yeshiva students. It is possible that the fact that many within the ultra-Orthodox public did enlist in military service during the War of Independence—particularly in areas under direct military threat, such as Jerusalem—led him to conclude that it was preferable to avoid confrontation with so radical a minority, and that, in any case, many members of the ultra-Orthodox community would continue to agree, in one way or another, to participate in the war effort (Shani & Lavi, 2024).

We are left with the impression that the rabbis’ opposition to allowing yeshiva students to undergo training and to learn how to bear and use arms for their own defense—and, if necessary, for the defense of the Yishuv as a whole—constituted a kind of breaking point in Ben-Gurion’s relationship with the rabbinical establishment. Ben-Gurion felt that he had approached them with considerable generosity and sensitivity, and that he had been prepared to offer an exemption from conscription to 400 yeshiva students even before the rabbis had formally requested it. He treated them with great respect and fully understood their need to preserve “Yavneh and its sages” [see below for more on the significance of this phrase]. In our assessment, he expected the rabbinical establishment to reciprocate by meeting him halfway, at the very least by allowing yeshiva students to undergo training in order to defend themselves.

On January 9, 1950, Ben-Gurion’s diary records a meeting he held with rabbis and heads of yeshivas:

A delegation of yeshiva heads came to see me […] They came to request the exemption of yeshiva students from security service, and although I informed them in advance that their request had already been granted, they elaborated at length, each in turn, on their arguments. They asked that a law be enacted granting the exemption; I explained to them that such a law would not be adopted. They then proposed regulations to be issued by the government or by the Minister of Defense, in case the Minister of Defense should change in the meantime (Ben-Gurion, 1950a, pp. 115–116).

Rabbi Zeltzer [so in the original; apparently referring to Meltzer], Ben-Gurion wrote in his diary, grounded his argument in a verse from the book of Ecclesiastes (9:18): “Wisdom is better than weapons of war.” Wisdom, he asserted, is Torah. Ben-Gurion understood from the rabbis’ remarks that they feared most yeshiva students would discontinue their studies if required to serve in the military, and would not return to them even after their release. They also refused to accept Ben-Gurion’s proposal to train the students at their place of study. Nor were they persuaded by Ben-Gurion’s claim that this had been the practice of Moses and Joshua son of Nun, who were military leaders; Moses and Joshua, they countered, were heads of yeshivas (Ben-Gurion, 1950a, pp. 115–116).[2]

These remarks are also corroborated by the testimony of Rabbi M. D. Tannenbaum, secretary of the Yeshiva Committee, who was present at the meeting: “Before the heads of the yeshivas began to express their views, Ben-Gurion pre-empted them by saying: ‘I wish to inform you that your request has already been granted.’ Nevertheless, the members of the delegation went on to set forth their arguments and to request that the ‘directive’ be given the force of law” (Re-examination of the exemption, 1986-1988, p. 8).

In the continuation of the meeting, the elder among the heads of the yeshivas, Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer, addressed those present. At the very outset of his remarks, he invoked an expression of profound symbolic significance in Jewish historical consciousness: “Give me Yavneh and its sages.” Rabbinic traditions concerning the destruction of the Second Temple recount that Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, during the Roman siege of Jerusalem, managed to leave the city and reach the Roman commander Vespasian. The latter, impressed by his wisdom, invited him to make a request. Rabban Yohanan did not ask for the rescission of the decree against Jerusalem, but rather: “Give me Yavneh and its sages”—that is, do not destroy Yavneh, and allow the Sanhedrin and the Torah scholars to relocate there and continue their activity after the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple. Indeed, according to tradition, Yavneh became the renewed center of Torah and rabbinic leadership—a kind of new “spiritual capital” that enabled the continued existence of Judaism after the destruction.

Below are Rabbi Meltzer’s foundational remarks in the original wording:

We have come to beseech His Excellency [Ben-Gurion] from the depths of our hearts: Give us Yavneh and its sages! […] We know well that, just as day differs from night and light from darkness, so too does this moment differ from the moment when these words were first uttered by Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai; then they were spoken before a besieger and an enemy, whereas today they are spoken before our brethren and our own flesh and blood. Then, it was a time of destruction and exile; today, it is a time of the establishment of the state and the return of children to their borders.

Yet we come before His Excellency empowered by the wisdom of Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, who understood that “Yavneh and its sages” are those who bear the Ark of the House of the Lord. This is our holy Torah, and so long as the Torah endures in Israel, the people too will endure and will not be destroyed among the nations; and since they will not be assimilated among the nations, they will assuredly aspire to return to their land and to rebuild it, as the Lord commanded us. It follows that the virtue of “Yavneh and its sages” is not only beneficial when Israel is in exile, but is all the more so when they dwell upon their own land, so that it may be made known to us and to our children that the House of Israel is not like the other nations, nor is our land like other lands (Re-examination of the exemption from conscription, 1986-1988, p. 8).

Rabbi Meltzer concluded his remarks as follows:

And behold, the Lord has granted us merit, and “Yavneh and its sages” have restored the crown to its former glory. With the destruction of European Jewry in the great catastrophe of our time, the yeshivas that had existed there for many hundreds of years have been transferred to our Holy Land, where they have been rebuilt, with God’s help, as an everlasting edifice—as the greatest center of Torah in the Jewish world, something that did not exist during Israel’s exile from its land. To these yeshivas, and to many more that will yet be established here, thousands of sons of Torah from abroad will ascend and come to quench their thirst and to know the Lord, as our prophets foresaw: “For from Zion shall go forth Torah, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem” (Re-examination of the exemption from conscription, 1986-1988, p. 8).

Rabbi Meltzer’s words, it was reported, made a profound impression on Ben-Gurion, who told his close associates that a figure of this kind arises in Israel only once every few generations. In one conversation, he went so far as to say that it seemed to him as though the words had been spoken by one of the prophets of Israel.

On May 9, 1950, the Deputy Speaker of the Knesset and one of the leaders of the National Religious Party, Dr. Yosef Burg, sent a letter to Chief Rabbi Herzog in which he complained about the abuse being made of the government’s willingness to grant exemptions from conscription to yeshiva students:

In recent months, young men have joined yeshivas whose Torah study was not truly their vocation; rather, upon reaching conscription age they registered as students in yeshivas. From this phenomenon, Heaven forbid, a desecration of God’s name may result. The attacks against the yeshivas and those who genuinely and sincerely study within them will multiply because of draft evaders who cloak themselves in the guise of yeshiva students.

Against this background, Burg appealed to Rabbi Herzog and requested that he instruct the rabbis not to issue exemption certificates to those who had entered a yeshiva only a year or less before reaching conscription age. “In this way,” he wrote, “we will be able to protect the exemption of genuine yeshiva students and to stand up to the criticism of informers for whom anything religious is an object of hostility” (Burg, 1950).

In an address delivered by Ben-Gurion to the senior command staff of the IDF on September 1, 1950, he made clear that the Jewish legacy is one of full popular mobilization for war:

The conscription laws established by Moses demonstrate that the army of Israel was a people’s army, in which the entire people were combatants. Thus, it was not desired that the faint-hearted participate in war. …These exemptions from the army did not stem from any belittling of the grave responsibility placed upon the military; on the contrary, they were intended to strengthen its morale and to free it from elements unable to devote themselves fully to the military mission (Ben-Gurion, 1950b).

On January 2, 1951, Ben-Gurion sent a letter to the Director General of the Ministry of Defense and to the Chief of Staff, in which he expressed the need to tighten the criteria for granting exemptions from conscription:

This exemption applies only to yeshiva students who are actually engaged in Torah study in yeshivas, and only so long as [emphasis in the original] they are engaged in Torah study in yeshivas. The exemption does not apply to a yeshiva student who leaves the yeshiva for any period of time (unless due to illness) and engages in another activity, even one undertaken at the behest of the yeshiva, such as teaching in camps and the like […] In cases where yeshiva students are found outside the bounds of their place of study in the yeshiva, even if on some form of mission, the military police are to detain them unless they can prove that they have lawfully completed military service, and to bring them to military intake centers (Report of the committee for formulating the arrangement, 2000, pp. 111–112).

Ben-Gurion’s disappointments with the conduct of the ultra-Orthodox establishment on the issue of military conscription appear, insofar as one can judge, to have found expression also in his approach to other questions concerning religion and state. At a cabinet meeting held on April 5, 1951, various issues in the sphere of religion–state relations were raised. During the meeting, harsh statements were voiced by the religious ministers against the government and its head, David Ben-Gurion. The prime minister did not remain silent. He responded to the religious ministers in blunt terms and made it clear that no one holds a monopoly over Judaism, and that every individual is entitled to act in accordance with his or her beliefs. “I do not think as you do on these matters,” he said to one of the most prominent rabbis:

Am I not a Jew? Do you wish to exclude all of us […] from the community of Israel? […] What is this obstinacy on the part of the rabbis? And regarding [the rabbis’ threat to appeal to American] Jewry—I say the following: “I live in my land, in my home. No Jew in America will tell me how I am to live, nor will I be intimidated by money. I live in this country; neither Jews nor non-Jews in America will tell me how I should live. Have I sold my soul?” (Minutes of cabinet meeting 39/1951, p. 21).

Rabbi Herzog is a dear Jew, but for me he is one Jew among others; his views and his religion do not bind me. Are those [who do not think as he does] not Jews? There are profound differences of opinion between us on fundamental matters of conscience—were you unaware of this? […] One cannot impose something upon the public when the public does not wish it. If there were a dictatorship here, the dictator could decree according to his will. But there is no dictator here, and we can act only on the basis of agreement” (Minutes of cabinet meeting 39/1951, p. 23).

These remarks by Ben-Gurion reflect a significant shift in comparison with his statements and actions during the War of Independence. At that earlier stage, he effectively granted ultra-Orthodox Judaism a kind of “monopoly” in matters of religion and state in general, and with regard to the conscription of yeshiva students in particular. In his statements at the cabinet meeting of April 5, 1951, however, he articulated an entirely different mode of thinking. The Orthodox stream, as may be inferred from his words, is an important current within Judaism, but not an exclusive one. The positions of secular Judaism are no less legitimate than those of Orthodox Judaism, and the latter must come to terms with this reality and act accordingly.

On October 20, 1952, David Ben-Gurion met with the Hazon Ish—Rabbi Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz, who was regarded at the time as the “greatest authority of the generation and a leading halakhic opinion.” Once again, Ben-Gurion gave expression to the deep reverence he felt toward the foremost rabbinic figures of that period. Despite his position as Prime Minister and Minister of Defense, he made it clear that he would come to meet Rabbi Karelitz in the latter’s home (The meeting in Bnei Brak, 1952).

At the outset of his remarks to the Hazon Ish, Ben-Gurion raised the question of whether Jews who had lived in the Diaspora within the framework of Jewish communities were capable of accepting sovereign authority here in the State of Israel. In addition, according to the documentation in his diary, Ben-Gurion addressed the ability of Jews to live together in the State of Israel amid internal disagreements concerning the practical implications of recognizing Israel as a “Jewish state” (Ben-Gurion, 1952).

In an implicit manner, the rabbi gave expression to the resolute stance of the religious public on the contested issues, including, inter alia, the question of the conscription of yeshiva students. In response to Ben-Gurion’s query as to how it would be possible to “live together” amid disputes over religion–state relations, the rabbi confined himself to the assertion: “For the time being, each side should act according to its conscience.” Ben-Gurion was not satisfied with this answer. Referring implicitly to the need for all Israeli citizens to contribute their share of military service, Ben Gurion addressed the Rabbi with the following statement: “There is a question of survival [of the State of Israel]; there is pikuach nefesh...Doesn’t he [ the Rabbi] acknowledge that love of Israel takes precedence over all?” (Ben-Gurion, 1952, p. 2).

The rabbi was not persuaded by Ben-Gurion’s questions and stated unequivocally—reflecting the position of the ultra-Orthodox parties—that “there is no Israel without Torah, and no Torah without Israel.” Nor did he stop there; he conveyed an unambiguous message to Ben-Gurion: “There are matters for which we will give our lives; we may be few, but when we give our lives we will be strong, and there will be no force that can prevail over us” (Ben-Gurion, 1952, p. 3).

Implicitly, the Hazon Ish made clear that priority should be accorded to the religious community over the secular community in shaping the way of life of the State of Israel:

“When two camels come toward one another, and there is a narrow path with room for only one camel, the camel bearing a load has the right of way […] We, the religious community, bear a heavy burden—the study of Torah, observance of the Sabbath, and adherence to the dietary laws. Therefore, the others must yield the path to us” (The meeting in Bnei Brak, 1952).

Ben-Gurion refused to accept this distinction: “Do non-religious Jews bear no burden? Is settling the land not a heavy burden? Are draining swamps, reclaiming wasteland, and safeguarding the state not heavy burdens? Even Jews who are entirely non-religious […] such as those engaged in settling the land and in defending you [emphasis in the original]” (The meeting in Bnei Brak, 1952).

The following exchange subsequently developed between the two, directly relating to the issue of conscripting yeshiva students:

Hazon Ish: It is by virtue of the fact that we (the guardians of the Torah) study Torah that they (the secular population) are able to endure.

Ben-Gurion: If those young men [the secular soldiers] were not defending you, the enemy would destroy you.

Hazon Ish: On the contrary—by virtue of our Torah study, they (the secular population) are able to live, work, and provide protection.

Ben-Gurion: I do not, Heaven forbid, disparage Torah. But if there are no living human beings, who will study Torah?

Hazon Ish: The Torah is the Tree of Life—the elixir of life.

Ben-Gurion: The defense of life is also a commandment. The dead do not praise the Lord (Meeting of President Yitzhak Navon with journalist Boaz Evron, 1981).

According to Yitzhak Navon, the conversation ended with each of the two figures remaining firmly entrenched in his own position, without having drawn closer to the other. After the meeting, Ben-Gurion told Navon that the rabbi was a fine and wise Jew, with beautiful and perceptive eyes, and that he was modest. Ben-Gurion wondered aloud where the rabbi derived his power and influence. (Meeting of President Yitzhak Navon with journalist Boaz Evron, 1981). He once again expressed, in blunt terms, his concern over the disputes surrounding religion and state in Israel, stating that the ingathering of the exiles was not a simple matter. There are many factors, he warned, that could tear Israeli society apart—but this was the most critical issue of all, posing a danger more severe than that of an external enemy (Meeting of President Yitzhak Navon with journalist Boaz Evron, 1981).

Ben-Gurion’s desire to demonstrate respect toward leading Torah authorities and to come to their homes is repeatedly reflected in the documentation of that period. At a cabinet meeting on July 12, 1953, Ben-Gurion reported on a meeting held in his office with three eminent rabbis—“elderly men and scholars,” as he described them: Rabbis Meltzer, Karelitz, and Tzvi Pesach Frank. Once again, he expressed the deep reverence he felt toward them: “I treat them with respect, and I felt somewhat embarrassed that they had to come to me” (Minutes of cabinet meeting 61/1953, p. 16).

The increase in the number of those seeking exemptions from conscription, on the one hand, and the growing concerns regarding the “abuse” of this entitlement, on the other, led ministers of defense from time to time to take steps aimed at limiting the scope of this phenomenon. In 1954 Defense Minister Pinhas Lavon issued an order to conscript to the army yeshiva students who were not seriously studying at the yeshiva. This decision raised various responses (Conclusions of the Committee on the Deferment of yeshiva students’ conscription into the IDF, 1995).

Ben-Gurion wrote to Pinhas Lavon on March 16, 1954:

It may be useful for you to know that there was never any agreement between me and any religious party regarding the exemption of yeshiva students. I took this step out of my own free “volition” […] Contrary to what I saw reported in one of the newspapers, the exemptions were not the product of a coalition agreement […] Incidentally, the growing number of yeshiva students, in my view, necessitates a change in the system of exemptions (Knesset Research and Information Center, 2018, pp. 2–3).

Lavon’s decision sparked a public outcry from the orthodox communities: Chief Rabbi Isaac Herzog came to the defense of the yeshiva students and wrote to Moshe Sharett:

Allow me to express my astonishment and my profound shock, to the depths of my soul, at the new approach to the question of the conscription of yeshiva students […] I have no doubt whatsoever that this approach will lead to the destruction of the centers of Torah—the remnant of the survivors in Zion, the source of our life to the forgetting of Torah, and to the ruin of Judaism.

The agreement reached at the time with Mr. David Ben-Gurion provided for the full exemption of yeshiva students for the entire duration of their studies in the yeshiva. This agreement has been strictly upheld to this day, both by the Ministry of Defense and by the yeshivas. A student who left the study halls of the yeshiva was reported to the Ministry of Defense. The comparison to the university is inappropriate: after four years of study, a university graduate completes his studies, whereas study in a yeshiva extends over many years.

A yeshiva student depends on a particular spiritual atmosphere. Experience shows that if he interrupts his studies for any purpose—even the most sacred—he will not return to the benches of learning. I am confident that Your Excellency wishes and is interested in preserving the flame of Torah in Israel […] I therefore await Your Excellency’s response regarding the continuation of the agreement as it has existed until now. In doing so, your Excellency and the Government of Israel will make a significant contribution to strengthening Torah study, to peace within the Yishuv, and to enhancing the stature of the state (Conscription of yeshiva students, n.d.).

Prime Minister Moshe Sharett, who assumed office following Ben-Gurion’s resignation from the government in late 1953, feared—justifiably—that this directive would undermine the stability of his government. His political standing was already rather fragile. He operated under the heavy shadow of David Ben-Gurion, who chose to withdraw to Sde Boker in the Negev. Yet even from there he continued to maneuver in ways that weakened Sharett’s position as Prime Minister. The persistence of terrorist attacks, together with widespread public frustration over the government’s perceived inability to respond effectively to this phenomenon, further eroded Sharett’s political standing.

Against this background, one can understand the apologetic tone of Sharett’s reply to Rabbi Herzog on March 8, 1954:

I have already ascertained that the information that reached Your Excellency was not accurate. There is no question of a general conscription of yeshiva students, but only of the conscription of those students who have already studied in a yeshiva for four years and who claim that they are still continuing their studies. The deferment of conscription for yeshiva students was determined in a manner similar to the deferment granted to university students. That is to say, the yeshivas were equated with universities with regard to their status vis-à-vis conscription. Students admitted to a university prior to fulfilling their military obligation are granted a deferment of four years, and it appears that the Ministry of Defense decided to apply the same arrangement to yeshiva students. As noted, I am still examining the matter thoroughly. For the time being, however, I deemed it appropriate to apprise Your Excellency of the facts as they have thus far become clear to me (Sharett, 1954a).

A few days later, on March 16, 1954, Sharett sent Rabbi Herzog another letter, in which he clarified that a ministerial committee headed by himself had been established to examine the arrangement governing the service of yeshiva students in the IDF. In any event, Sharett emphasized, yeshiva students would not be required to enlist in the IDF so long as Torah study constituted their full-time occupation and they had no other livelihood. At the same time, the principal issue to be addressed would be how to prevent abuse of this arrangement by young men who, in practice, neither study in a yeshiva nor enlist in military service (Sharett, 1954b).

Against this background, it is highly likely that Sharett demanded that Lavon postpone the implementation of the move:

The directive to conscript yeshiva students who have completed four years within the yeshiva walls has aroused great agitation and a storm of protest within ultra-Orthodox circles. The Chief Rabbinate, the Minister of Religious Affairs, and the leadership of Agudat Israel have approached me on this matter. I am aware that members of a delegation of rabbis from the United States who are currently in the country are also expected to approach me on the same issue […] Under the prevailing circumstances, I see a need to request that you postpone the implementation of the directive until the matter can be clarified between us or discussed at a cabinet meeting (Re-examination of the exemption from conscription, 1986-1988, pp. 9–10).

The Late 1950s

In a letter dated June 4, 1957, to the Deputy Minister of Education, Moshe Unna of the National Religious Party, Ben-Gurion regretted the sweeping exemption arrangement granted in 1948. In the letter, Ben-Gurion proposed granting an exemption from conscription to one hundred yeshiva students who would agree to engage in teaching for a period of four years. In return, they would be required to undergo basic military training for three months. The years of teaching would be recognized as equivalent to full military service as stipulated by law. Upon completion of their teaching service, they would be registered as reserve soldiers in the IDF, like other servicemen (Ben-Gurion, 1957).

In the correspondence between Ben-Gurion and Rabbi Herzog in 1958, the dramatic turn that had taken place in Ben-Gurion’s position on the conscription of yeshiva students since the sweeping exemption he granted during the War of Independence is revealed in stark terms. In a letter dated October 27, 1958, addressed to the Prime Minister and Minister of Defense, Rabbi Herzog referred to rumors concerning changes in the policy on the conscription of yeshiva students into the IDF. His words reflect a marked shift from those he had expressed in 1948: “I was deeply shaken, and my heart broke within me, upon hearing the report that there has arisen an intention to introduce changes in the existing status of yeshiva students, whose conscription has been deferred so long as they devote their days to Torah. I therefore found it my duty to come before Your Excellency with the following remarks” (Herzog, 1958).

Against this backdrop, the rabbi describes at length in his letter to Ben-Gurion the profound devastation that befell Jewish communities in Europe. This destruction led to the annihilation of major centers of Torah study—yeshivas, study halls, and synagogues. Those who survived came to the Land of Israel in order to restore and rebuild the spiritual life of the country. This reality, the rabbi maintains, must surely have been before Ben-Gurion’s eyes when he decided to grant yeshiva students an exemption from conscription. He concludes his letter with the following words:

An obligation rests upon the people dwelling in Zion […] to grant yeshiva students, who have been entrusted with safeguarding the spiritual assets of the nation a full exemption from any form of military service, so long as they dwell in the tent of Torah. These students carry out their studies with self-sacrifice and immeasurable devotion under economic conditions of crushing hardship. They too are mobilized, standing guard over the security of the Torah of Israel and its heritage, in which its glory resides and for whose sake we have reached this point [emphasis in the original]. These [the yeshiva students], no less than those [the combat soldiers], safeguard the nation’s fundamental possessions (Herzog, 1958).

At the conclusion of his remarks, the rabbi demanded that “no change whatsoever be made to this status [of the yeshiva students], not even the slightest deviation” (Herzog, 1958).

Rabbi Herzog’s words, it may be inferred, greatly angered Ben-Gurion, who responded to him in rather blunt terms:

When I exempted yeshiva students from military service ten years ago, their numbers were small. I was told, this was the only country in which Torah scholars devoted to study for its own sake still remained. Since then, the situation has changed. The number of yeshiva students has grown […] and has reached into the thousands. Here, in Israel we are all Jews, and our security depends solely upon ourselves. This is, above all, a profound moral question—whether it is morally justified that the son of one mother should be killed in defense of the homeland, while the son of another mother sits safely in his room and studies. The majority of Israel’s young people risk their lives to the point of death.

I would not presume to confront you with an explicit halakhic ruling of Maimonides, according to which, in a milhemet mitzvah, all go forth—“even a bridegroom from his chamber and a bride from her canopy” […] It cannot be that thousands of young men are incapable of bearing arms on the day of command […] One must not forget that we are not continuing a life of exile here, dependent upon the goodwill of others […] We stand on our own authority, and the burden of security rests upon us ourselves. This is a great privilege that we have attained after centuries, and in my view this privilege imposes an obligation upon every young person in Israel.

I cannot find in the Torah any basis for the claim that those who study Torah were exempt from the defense of the homeland […] I cannot, under any circumstances, agree with your assertion that “because of the yeshiva students we have reached this point.” They did not build the land. They did not risk their lives for its independence (although some of them did), and they possess no special rights that other Jews do not possess […] Nor does military service diminish Torah study. In a sovereign Israel, Torah is incomplete if it does not also encompass the doctrine of defending the people and the homeland. Without the continued existence of the people of Israel, there will be no Torah, and the preservation of the nation’s life takes precedence over all else. Precisely those who honor Torah scholars (and I dare say that I am among them) and who wish to uphold their dignity must ensure that they do not separate themselves from the collective and exempt themselves from the most sacred obligation of all—the obligation to defend their parents, their families, their communities, and their people (Ben-Gurion, 1958).

In the continuation of his letter, Ben-Gurion proposes a form of compromise that had already been raised in the early 1950s and rejected by the Council of Rabbis. The wording of his remarks clearly indicates the extent to which he was careful to avoid any impression that he was seeking to impose a particular arrangement on yeshiva students:

I proposed—I did not order, but merely proposed—that yeshiva students who devote their entire lives to the study of Torah should undergo basic training for three months, while others should serve in the army like every young person in Israel. I made this proposal to the Members of Knesset of Agudat Israel. The Director General of the Ministry of Defense made the same proposal to several heads of yeshivas […] and I ask you to use your influence with the heads of the yeshivas so that they themselves will demand, at the very least, basic training of three months for all yeshiva students (Ben-Gurion, 1958 [emphasis in the original]).

In parallel to this correspondence, the issue of the exemption granted to yeshiva students from military service was also discussed within the government. At a cabinet meeting held on March 16, 1958, Minister Mordechai Bentov of Mapam invoked a comparison attributed to Ben-Gurion—between combat soldiers in the IDF and yeshiva students who enjoy exemption from military service:

Who possessed a greater Jewish consciousness—the young men of the Palmach, or those yeshiva students. The young men of the Palmach did not know the entire Bible and were unfamiliar with the prayers. However, they sacrificed their lives [for their land]. The yeshiva students, on the other hand, […]—some of whom indeed fell in battle, but most of them did nothing and to this day believe they should be exempt from all service Why should young rabbis not be required to serve in the army? In the past, priests stood at the head of the army; in France, Catholic priests serve in the military. Why should it be said that those young men who went forth to risk their lives for their people and their homeland lacked Jewish consciousness? (Minutes of cabinet meeting 31/1958, p. 51).

At a cabinet meeting held on April 20, 1958, the issue of the exemption of yeshiva students from military service was discussed. Ben-Gurion expressed particular indignation toward the son of a well-known rabbi who, according to Ben-Gurion, had evaded military service during the War of Independence. The War of Independence, Ben-Gurion asserted, was a milhemet mitzvah—an obligatory war—and all were therefore required to enlist in the campaign. The son of that rabbi, he argued, was well versed in halakha and nonetheless chose not to enlist to aid his brethren in wartime (Minutes of cabinet meeting 36/1958, p. 34; Minutes of cabinet meeting 48/1958, p. 22).

However, a summary of a meeting held in 1957 between heads of yeshivas and the Director General of the Ministry of Defense, Shimon Peres—drafted by the secretary of the Yeshiva Committee, Rabbi M. D. Tannenbaum, and published on November 13, 1958—presents an entirely different picture. The letter reflects a willingness on the part of the Ministry of Defense to accept, in a sweeping manner, the rabbis’ position on the issue of military service. No expression is given to Ben-Gurion’s critical views toward the ultra-Orthodox establishment or toward the question of conscription into the IDF. The following were the main points discussed at the meeting:

- The position and request of the heads of the yeshivas was that no change be made to the existing situation.

- When a yeshiva student reaches the age of conscription, he is to be asked by the recruitment office whether he wishes to continue his studies in the yeshiva or to enlist in the IDF. Should he declare his wish to continue his studies in the yeshiva, his military service will be deferred in the same manner and under the same arrangements as have applied to him to date.

- This question will be posed again to each yeshiva student upon reaching the age of 25. If the student states that he wishes to continue his studies in the yeshiva, he will continue to receive a deferment.

- Upon reaching the age of 29, the question will be posed to the yeshiva student for a third time. If he responds that he wishes to continue his studies in the yeshiva, he will continue to receive a deferment, as is customary at present (Report of the committee for formulating the arrangement, 2000, p. 112).

A Retrospective View

Several months prior to the outbreak of the Six-Day War, and when he was no longer part of the political establishment, Ben-Gurion reiterated a position that reflected regret over the exemption granted to yeshiva students during the War of Independence. In his reply to a letter from a private citizen he expressed support for initiatives aimed at their conscription into the IDF through special arrangements. He explained that immediately after the establishment of the state, representatives of Agudat Israel had approached him, arguing that all centers of Torah study abroad had been destroyed and that only in Israel were there a small number of young men wishing to study in yeshivas. They requested that these students be exempted from military service, and Ben-Gurion agreed.

In the meantime, however, Ben Gurion continued, it became clear that numerous yeshivas existed in countries such as France, Switzerland, and the United States, among others. Within Israel as well, the number of yeshivas had grown considerably, and in Ben-Gurion’s view there was no longer any justification for exempting their students from military service. It was inconceivable, he argued, that thousands of young men would not receive military training at a time when the State of Israel was surrounded by enemies openly declaring their intention to destroy it.

And once again, in a similar vein, in a letter dated June 20, 1971, to Gerald Stern of Cape Town—who had written to Ben-Gurion asking whether yeshiva students would be exempt from military service—Ben-Gurion acknowledged that he bore responsibility for granting the exemption from conscription to yeshiva students:

I am to blame for this, because in those days (immediately after the establishment of the state), the “religious” parties told me that the centers of yeshivas in all the countries of the Diaspora had been closed, and that it was therefore necessary to ensure that all young men who wished to study Talmud would be free from military service. I agreed to this at the time because I believed that they were referring to a limited number. In the meantime, it has become clear that thousands are exempting themselves from military service, and there is no doubt that the law enacted immediately after the establishment of the state must be repealed (Ben-Gurion, 1971 [quotation marks and emphasis in the original]).

It thus emerges that the worldview of Rabbi Isaac Halevi Herzog—which combined deep concern for the security of the State of Israel with a commitment to ensuring the continued existence of the world of Torah—also took root among rabbis who were regarded as leading authorities of their generation many years later. Thus, for example, in a letter from October 1979, Rabbi Shach, in his capacity as president of the Yeshiva Committee, stated that “the right granted to a yeshiva student to benefit from the deferment of his conscription into the army exists solely on the condition that ‘Torah study is his sole occupation,’ and that he engage in no material pursuits, whether during yeshiva hours or outside them. All the great sages of Israel lent their support to this regulation and regarded it as an inviolable condition” (Stern, 2025).

In a letter of similar content dated August 1983, Rabbi Aharon Yehuda Leib Steinman wrote in his own hand: “I, the undersigned, hereby declare that I will not issue, under my signature, an approval for a student in connection with the deferment of conscription except for one who is engaged in no activity other than his studies in the yeshiva, and for whom Torah study is his sole occupation” (Stern, 2025).

Summary and Conclusions

The subcommittees of the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee are usually been accorded considerable esteem and recognition. This is primarily due to the diverse composition of their members, which enable them to hear a wide range of views, including sharply opposing perspectives. The approach adopted by the members of the committees is generally substantive and professional rather than political in nature. The security agencies provide the committees with classified materials, with the clear understanding that their contents will not be disclosed to the general public.

The subcommittee of the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense committee established in 1986 constituted a clear departure from these “classical” characteristics. It lacked the requisite diversity in the composition of its members and did not provide sufficient scope for the presentation of opposing viewpoints. An overwhelming majority of its members supported the revocation of the exemption from conscription granted to yeshiva students.

Against this background, it is perhaps possible to understand the refusal of the heads of the yeshivas to appear before the committee. The position of the yeshivas was instead represented by the Council of Heads of Yeshivas, which operates in cooperation with the Ministry of Defense on matters relating to the exemption of yeshiva students.

Given the composition of the committee, its conclusions were largely foreseeable. The committee expressed the view that the arrangement exempting yeshiva students from security obligations required modification, since the circumstances that had justified its establishment at the time of the state’s founding no longer prevailed. The arrangement had long since exceeded its original intent and departed from the bounds of reasonableness, both because of the steadily growing number of those making use of the exemption and in light of the security challenges confronting the State of Israel.

It may be assumed that these conclusions were acceptable to a majority of the citizens of the State of Israel. In practice, however, they were unable to advance a resolution to the problem. The reason for that was clear: Those who were expected to articulate the position advocating the continuation of the exemption for yeshiva students were almost entirely absent from the committee’s deliberations. As a result, the committee’s conclusions were consigned to the drawers of government offices and the State Archives, and contributed nothing to the advancement of a solution to the issue.

It must be stated candidly that even a more balanced representation of the ultra-Orthodox parties on the committee would not necessarily have guaranteed the achievement of a consensual position between the sides. Nevertheless, it could at least have been argued that a genuine effort was made to understand the positions of the other side and to explore innovative, nonconventional solutions that might have advanced—even if only incrementally—a resolution acceptable to both parties.

It may be said that the committee presented the historical background in a balanced manner and gave full expression to the positions of both sides during the early years following the establishment of the state. The documentation indicates that the exemption from conscription granted to yeshiva students was not the result of coalition-based or partisan considerations. Nor was it granted in response to substantial pressure exerted by the religious public on the state’s leadership. Rather, insofar as can be discerned, it was a personal decision by Ben-Gurion, conveyed to the Council of Heads of Yeshivas at the very outset of his meeting with them—prior even to any attempt on their part to persuade him to grant an exemption from military service to yeshiva students.

It is difficult to understand how a leader as measured and experienced as David Ben-Gurion arrived at such a fateful decision in such an independent manner and without any systematic research or review by his staff. This puzzle is heightened by the fact that the decision was taken at a time when the State of Israel was facing a very real threat of annihilation, and when manpower inferiority constituted a critical factor in ensuring the state’s security. Even if Ben-Gurion had wished to grant an exemption, he could have confined it to a limited number of students, leaving it to the heads of the yeshivas to determine who would be eligible. He could also have stipulated that a full exemption would take effect only after the conclusion of the war, once it was clear that the State of Israel no longer faced an existential threat.