Strategic Assessment

Empathy is a universal human capacity essential to social cohesion, yet it is highly vulnerable to weaponization. The aftermath of the October 7 Hamas massacre provided a dramatic case study of this phenomenon. Instead of universal condemnation, segments of Western intellectual and activist discourse produced a striking moral inversion, systematically redirecting empathy from victims to perpetrators while rationalizing the atrocities.

Drawing on insights from moral philosophy, psychology, and postcolonial theory, this article applies Critical Discourse Analysis to forty key texts, to analyze this narrative inversion. It argues that this response is the result of a structural collapse of universal principles into identity politics. The analysis identifies four recurring discursive patterns that drive this process: reframing terrorism as resistance, delegitimizing victims through colonial coding, declaring performative solidarity, and framing Israel’s military response as genocide.

By tracing these dynamics to similar patterns following 9/11 and during European jihadist attacks, the paper reveals a critical vulnerability in the cognitive resilience of open societies. The findings lead to policy recommendations for communication strategies designed to reaffirm universality, counter disinformation, and protect democratic legitimacy in the contemporary information battlespace.

Keywords: Empathy, Universalism, Identity Politics, Moral Relativism, Postcolonial Theory, Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), Delegitimization, Cognitive Security, Cognitive Warfare.

Introduction

Empathy is a fundamental human instinct, rooted in neurobiology and cultural evolution (Batson, 2011; Decety & Lamm, 2006). It alerts us to suffering but cannot, by itself, establish justice or truth. That role belongs to universal moral principles, which stand above circumstance, culture, and identity.

This paper rejects moral relativism and rests on a foundational premise: while perception is subjective, truth is not. Even uncertainty conforms to some kind of order; ethics, too, must rest on universals. Philosophical traditions diverge on this point. In the Enlightenment tradition—from Spinoza (as a precursor) and Kant to later heirs such as Rawls—moral judgment is anchored in universal principles that restrain partiality; according to this view, empathy must be guided and not left to rule (Kant, 1998/1785; Rawls, 1971; Spinoza, 2002/1677). By contrast, postmodern thinkers often treat morality as contingent narrative, undermining the claim to a universal basis (Baudrillard, 1994/1981; Deleuze, 1994/1968; Derrida, 1976/1967; Foucault, 1980; Lyotard, 1984/1979).

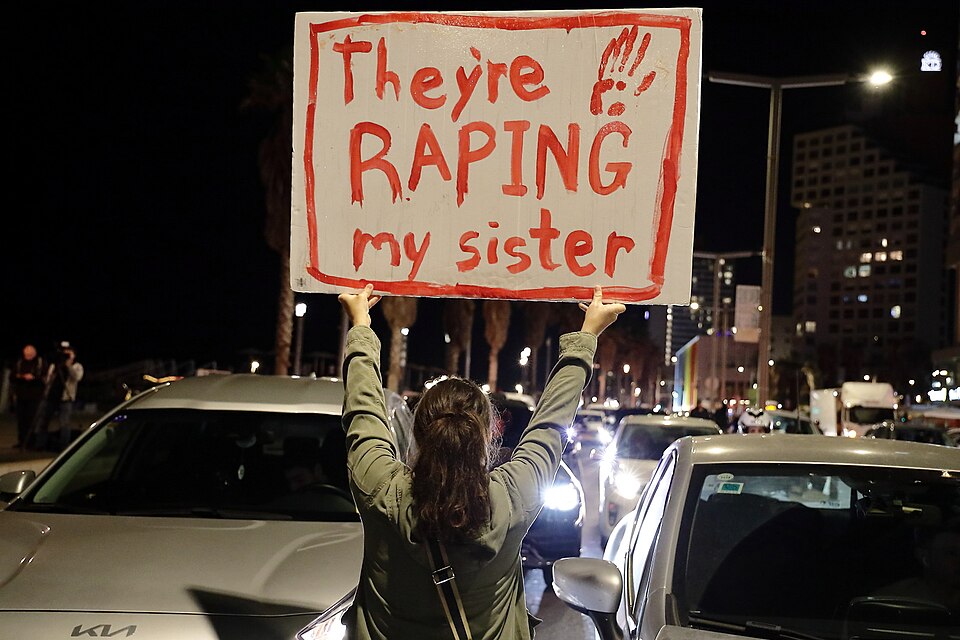

This distortion was dramatically exposed in the aftermath of the Hamas massacre of October 7, 2023—the deadliest day for Jews since the Holocaust. By any universal standard, the deliberate targeting of civilians through mass murder, rape, mutilation, and kidnapping demands unequivocal condemnation. Yet in certain progressive Western circles, the response was ambivalent. Atrocities were contextualized, even rationalized, as the “inevitable” outcome of colonial oppression. In this inversion, perpetrators were judged not by their actions but by their identity, and empathy flowed toward aggressors rather than victims. These responses were not monolithic: Alternative progressive voices did condemn the October 7 atrocities and reaffirm universal principles. The analysis that follows identifies dominant trends in specific activist, academic, and media networks, while acknowledging diversity within these milieus.

This phenomenon raises urgent questions for both political theory and national security. Why does empathy, an instinct so deeply embedded in human psychology, become inverted in this way? How does ideology transform an impulse to care into a justification for cruelty? And most critically for Israel, how does selective empathy affect legitimacy, security, and the conduct of information warfare in a world where perception increasingly shapes strategic outcomes?

To address these questions, the paper combines three perspectives. Philosophically, it traces the erosion of Enlightenment universalism in the face of identity-based moral relativism. Psychologically, it identifies the cognitive and emotional mechanisms that distort empathy and lead to ideological inversions. Strategically, it analyzes the weaponization of empathy as a tool of cognitive warfare aimed at undermining the resilience of democratic states.

The argument advanced here is that empathy, when untethered from universal principles, becomes a liability: morality collapses into partiality, the oppressed are granted moral immunity, and supposed oppressors are denied standing. This selective empathy corrodes the universal foundations upon which liberal democracies—and Israel as a Jewish and democratic state—depend for legitimacy and survival. For Israel, this is not a philosophical debate but an urgent national security challenge: when empathy is inverted and weaponized, it erodes legitimacy, constrains policy, and weakens resilience in the cognitive domain. In today’s environment, where perception is as critical as deterrence, the weaponization of empathy must therefore be recognized as both an ethical problem and a national security challenge.

Methodologically, the paper employs Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of forty texts—including academic essays, activist manifestos, and media interventions—published between October 7, 2023 and March 2024. These texts were selected because they exemplify dominant discursive trends in progressive intellectual and activist circles. This approach makes it possible to identify recurring patterns—including the reframing of atrocities as resistance, the delegitimization of victims through “settler”/complicity coding, performative declarations of solidarity, and the framing of Israel’s response as genocide—and to highlight their strategic consequences for Israel and for the resilience of liberal democracies (Fairclough, 2010; van Dijk, 2008).

The paper is structured as follows: the first section outlines the theoretical framework, reviewing literature from psychology, moral philosophy, and postcolonial studies. The second explains the methodology and corpus. The third presents the empirical findings from the discourse analysis. The fourth section provides the core analysis and discussion, diagnosing the mechanisms of this inversion and tracing their strategic implications. The final section offers policy recommendations to reinforce universal principles and cognitive resilience in liberal democracies.

Theoretical Framework

This section builds the multidisciplinary framework required to diagnose the weaponization of empathy. It traces a clear line of vulnerability: from empathy’s neurobiological origin as a partial instinct, to the philosophical collapse of the universal principles that sought to discipline it, and finally to the ideological take-over of this undisciplined emotion by identity politics.

- Empathy as a Neurobiological Instinct

Empathy has long been understood as a foundational human instinct—with rare neurological exceptions such as psychopathy or extreme sociopathy – that enables cooperation, social cohesion, and moral conduct. In evolutionary terms it functioned as a survival mechanism: Early human groups that could recognize and respond to the suffering of others were more likely to endure (Batson, 2011). Yet empathy is not impartial. Social neuroscience demonstrates that individuals experience stronger empathic responses toward in-group members than toward outsiders (Decety & Lamm, 2006). This partiality underscores why empathy alone cannot serve as a moral compass. Without universal principles, it risks being redirected by ideological or identity-based filters.

- Moral Philosophy: Universalism Versus Relativism

The Enlightenment tradition sought to discipline empathy by grounding it in universals. Kant’s categorical imperative demanded that moral action be judged according to maxims that could be willed as universal law (Kant, 1998/1785). For Spinoza, in the Ethics, all beings are modes of the same Nature, bound by necessary laws; perception may distort reality, but it cannot abolish its structure (Spinoza, 2002/1677). Rawls, in the same vein, later echoed this commitment by proposing that principles of justice are those chosen under a “veil of ignorance,” where individual identity and interests are bracketed (Rawls, 1971). Equally emblematic was the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which proclaimed liberty, equality, and dignity as inherent rights binding on all, rather than culturally contingent values (France. National Assembly, n.d.).

To this genealogy, Friedrich Nietzsche adds an important dimension. Rejecting transcendent universals and metaphysical absolutes, he reads becoming through will to power: an immanent dynamic of force-relations, contestation, and recurrent reconfiguration (Nietzsche, 2002/1886). This is not a moral universal, but an account of how life displays regularities without appeal to transcendence, thereby denying arbitrariness. What appears chaotic is patterned by the interplay of forces—colliding, recurring, and reorganizing in shifting configurations—without immutable laws. In this sense, Nietzsche converges with Spinoza in rejecting both transcendental dogma and moral relativism. Both affirm necessity and structure without appealing to divine or cultural absolutes, even though their metaphysical frameworks diverge (Nietzsche, 2002/1886; Spinoza, 2002/1677).

By contrast, some postmodern and deconstructionist approaches question the very status of universals. Foucault emphasized the contingency of “regimes of truth,” while Derrida underscored the instability of meaning (Foucault, 1980; Derrida, 1976/1967). In these frameworks, universals are often recast as discursive constructs, and morality becomes plural and a matter of perspective (Lyotard, 1984/1979; Deleuze, 1994/1968; Baudrillard, 1994/1981). While such critiques illuminate the exclusions historically embedded in appeals to universality, they also risk eroding the possibility of a shared moral ground—precisely the ground needed to check partiality and to discipline empathy.

- French Theory and the Temptation of Illiberal Revolutions

The impact of these ideas was amplified by their transatlantic migration. While Foucault and Derrida’s critiques were situated within a specific European context, their diffusion into American universities during the 1970s and 1980s—popularized as French Theory—reshaped U.S. academia (Cusset, 2008). What were originally subtle critiques of universality and power were sometimes simplified into a worldview where truth was recast as narrative, morality as perspective, and universality as exclusionary (Cusset, 2008).

The paradox became particularly visible in the Western reception of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Several French intellectuals, most notably Michel Foucault, romanticized the uprising as an authentic expression of spiritual resistance to Western modernity (Afary & Anderson, 2005). Yet the regime that emerged contradicted principles of secularism, women’s rights, and individual liberty that the Enlightenment and human rights discourse had sought to uphold (Afary & Anderson, 2005).

- Orientalism and the Logic of Essentialized Identities

As Edward Said argued, “Orientalism” is not merely a set of descriptions but a regime of representation that encodes power into perception (Said, 1978). According to Said, Western intellectual traditions often projected simplified, symbolic identities onto the “East,” portraying it as an object of fascination, victimhood, or moral purity, while simultaneously coding the West as inherently dominant or oppressive. While Said’s critique targeted imperial representations, its later appropriation in postcolonial and progressive discourse often reproduced the same essentialism in reverse: the non-West was cast as perpetually virtuous and wronged, while Western democracies were positioned as oppressive in essence.[1]

- The “New Proletariat”

A further dimension of this genealogy is the shift from economic class struggle to identity-based struggle. Where once the “oppressed” were defined primarily by socio-economic status, they are now defined by race, ethnicity, and post-colonial position. This transformation was strategic. In much of the West, the traditional working-class base of the left—historically the backbone of socialist and progressive politics—has drifted toward nationalist and even far-right movements, attracted by appeals to sovereignty, cultural preservation, and resistance to globalization. Deprived of this constituency, progressive movements sought a new “proletariat” in racial minorities, immigrant communities, and post-colonial populations, recasting them as the symbolic victims of systemic injustice.

In this symbolic reframing, Jews—despite centuries of persecution culminating in the Holocaust—were increasingly recoded as “white,” “colonial,” or “bourgeois.” This erasure of historical trauma and cultural diversity was necessary to maintain the dichotomy between “oppressed” and “oppressor.” Jewish vulnerability, both past and present, was minimized or denied, while antisemitism itself was often reframed as a form of “anti-colonial resistance.” By contrast, Muslim immigrants, racial minorities, and post-colonial groups were elevated to the role of the new proletariat: bearers of systemic victimhood whose suffering was assumed to confer moral immunity.

This reconfiguration has profound consequences. It replaces universal principles of justice with a form of moral essentialism in which identity, rather than conduct, determines moral worth. As Laurent Bouvet observed in his analysis of cultural insecurity, the collapse of universalism into group-based claims fragments the moral order and erodes the possibility of impartial standards (Bouvet, 2015).

This process is also driven by a powerful dynamic of “competitive victimhood,” where moral legitimacy is treated as a zero-sum game. For one group to be elevated as the ultimate symbol of oppression, the historical and present-day victimhood of competing groups, such as Jews, must be minimized, erased, or delegitimized (Chaumont, 1997; Taguieff, 2002).

- Psychological Mechanisms of Distorted Empathy

Beyond ideology, psychological mechanisms deepen the vulnerability of empathy to distortion. Trauma bonding, first theorized in the study of abusive relationships, describes the paradoxical attachment of victims to their aggressors, a psychological attempt to regain coherence or control (Dutton & Painter, 1993). On a societal scale, this mechanism can manifest as solidarity with violent actors framed as liberation movements, even when their methods violate fundamental rights.

Similarly, Anna Freud’s concept of “identification with the aggressor” describes how individuals or groups internalize the worldview of those who wield power over them (Freud, 1992/1936). In postcolonial Western discourse, this mechanism often manifests as a compulsive need to adopt the narrative of the perceived “subaltern,” even when that narrative entails hostility toward liberal-democratic norms. The result is not genuine solidarity, but submission disguised as empathy. This dynamic is powerfully captured in Soumission (Houellebecq, 2015), where the Western intellectual elite gradually embraces an authoritarian ideology—not through coercion, but through resignation, moral fatigue, and the psychological comfort of surrender.

Barbara Oakley’s notion of “pathological altruism” adds another dimension: compassion detached from discernment can lead to policies that harm both self and others (Oakley et al., 2012). It marks the point where empathy ceases to be prosocial and becomes self-destructive. Gad Saad extends this to “suicidal empathy,” whereby moral instincts, unmoored from universals, undermine survival itself (Saad, 2020). He illustrates this through the uncritical embrace of mass immigration policies—framed as humanitarian imperatives—yet blind to long-term effects such as cultural fragmentation or the importation of illiberal norms and ideologies.

- Performative Morality and Virtue Signaling

The ideological and psychological distortions of empathy are amplified by the performative nature of modern public discourse. As Pierre Bourdieu theorized, public discourse often functions as a field of symbolic capital, where recognition and prestige are distributed according to visible alignment with dominant moral norms (Bourdieu, 1991). Building on Bourdieu’s notion of symbolic capital, recent empirical research demonstrates how this mechanism operates in the form of moral grandstanding—a status-seeking expression of virtue signaling in which individuals use moral discourse to enhance their standing within a group (Grubbs et al., 2019). Social media amplifies this dynamic: outrage is rewarded, nuance penalized, and empathy reduced to symbolic capital rather than universal principle.

This dynamic echoes Max Weber’s distinction between the “ethic of conviction” (acting from principle regardless of consequences) and the “ethic of responsibility” (acting with awareness of consequences) (Weber, 2004/1919). Extreme progressivism, in its theatrical forms, often sacrifices both: conviction is reduced to rhetorical purity, and responsibility to performative alignment. Kantian duty is abandoned in favor of appearances. In such an environment, empathy becomes a token of group identity.

Conclusion of Framework

Empathy is universal in potential yet selective in practice. Enlightenment universalism sought to discipline it through shared principles; postmodernism destabilized universals; identity politics has reallocated moral worth along symbolic lines. Reinforced by psychological reflexes and performative incentives, these shifts created the conditions in which empathy itself could be weaponized—legitimizing some violence while excusing others.

Methodology

This study employs a qualitative approach grounded in Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to investigate how empathy was framed, distorted, and selectively allocated in segments of progressive Western discourse following the Hamas massacre of October 7, 2023. CDA, as developed by Fairclough and van Dijk, provides analytical tools to uncover how language reflects and reproduces power relations, ideological assumptions, and moral framings (Fairclough, 2010; van Dijk, 2008). This approach is particularly suited for examining the convergence of psychological mechanisms, philosophical concepts, and political narratives in the cognitive domain of national security.

Research Design

The research design is interpretive and exploratory rather than experimental. The goal was not to measure causal variables statistically but to map recurring discursive patterns. The analysis combined three dimensions:

- Philosophical – how relativist and postcolonial frameworks undermine universality.

- Psychological – how mechanisms such as trauma bonding, identification with the aggressor, and pathological altruism reinforce ideological framings (Dutton & Painter, 1993; Freud, 1992/1936; Oakley et al., 2012; Saad, 2020).

- Strategic – how selective empathy impacts Israel’s legitimacy and the resilience of liberal democracies in information warfare.

Corpus

The corpus comprises approximately forty texts produced between October 7, 2023, and March 2024—a period of intense public debate encompassing two distinct yet connected phases. The first captures the immediate reactions, in which some actors openly justified or romanticized the massacre itself, with little or no recognition of Israeli civilians as victims. The second covers the subsequent reframing, during which attention shifted almost entirely to Israel’s response and the original atrocity was morally displaced or erased.

The corpus includes academic essays, activist manifestos, and media interventions in English and French, drawn from mainstream outlets, academic blogs, activist organizations’ websites, and major social media platforms. Selection emphasized influence and paradigmatic value rather than statistical frequency, consistent with CDA’s qualitative orientation.

Three criteria guided inclusion: (1) Authority—authors or institutions with recognized influence in shaping discourse (e.g., Judith Butler; Harvard Palestine Solidarity Groups); (2) Visibility—texts achieving wide circulation or citation (e.g., Raz Segal’s “textbook case of genocide” article); (3) Representativeness—clear exemplification of one of the core discursive patterns (e.g., the BLM Chicago paraglider graphic as performative solidarity).

Influence was measured not by outcomes but by a text’s capacity to serve as an influential model within the broader discursive inversion.

Analytical Strategy

Coding proceeded iteratively. A pilot analysis of 10 texts was first conducted to refine categories and indicators before applying them to the full corpus. The final coding scheme included four recurring categories: (i) reframing perpetrators as anti-colonial or “armed resistance” actors; (ii) delegitimizing victims through “settler”/complicity coding; (iii) performative declarations of solidarity; and (iv) framing Israel’s military response as “genocide.” For each category, specific linguistic and rhetorical markers were identified in advance (e.g. labels such as “settler,” “resistance,” “genocide,” or binary slogans). These markers served as a coding guide, ensuring that interpretations remained consistent across texts and preventing ad hoc shifts in judgment.

Operationalization of the Framework

The framework was operationalized by integrating Fairclough’s triadic model: (i) micro-level textual features (lexicon, modality, transitivity); (ii) discursive practices (production, circulation, uptake across activist, academic, and media arenas); and (iii) macro-level social practices (postcolonial and identity-based moral frameworks). In line with van Dijk’s socio‑cognitive approach, attention is paid to the mental models and social representations that guide selective empathy (e.g., moral categorization of “oppressed/oppressor”), thereby linking linguistic choices to shared ideological schemas.

Ethical Considerations

All sources analyzed were public texts. Identifying details of individual authors are anonymized where necessary to protect privacy while preserving the integrity of the discourse analysis.

Limitations

As with all qualitative approaches, the findings are interpretive rather than statistical and do not claim exhaustiveness. The relatively small corpus cannot represent all discourses produced after October 7. However, CDA allows individual texts to be linked to broader ideological and cultural trends, providing insight into recurring mechanisms of selective empathy and their implications for national security.

While the study did not employ formal intercoder reliability testing—a method more common to quantitative content analysis—, its qualitative rigor was ensured through alternative measures, including predefined coding categories, linguistic markers, and iterative consistency checks. This approach mitigated subjectivity and strengthened confidence that the findings reflect recurring structural mechanisms rather than isolated interpretations.

Findings: October 7 and the Discursive Inversion of Empathy

The Hamas massacre of October 7, 2023, constitutes a moral watershed in contemporary conflict. From the perspective of universal ethics, the atrocity should have elicited unequivocal condemnation. Yet, in segments of Western progressive discourse, the attack was not narrated as a crime against humanity but reframed as a symptom of colonial oppression and resistance.

To enhance the empirical clarity of the study, the analysis below provides representative examples drawn from forty texts. These examples are not an exhaustive catalogue but illustrative cases that reveal how a common discursive logic appeared across different arenas of public discourse. This section applies Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to highlight recurring discursive patterns, culminating in the most significant move: the framing of Israel’s military response as genocide.

- Reframing Terrorism as Resistance

A recurrent discursive pattern was the reframing of the October 7 massacres as resistance. Prominent intellectuals, such as Judith Butler (Bherer, 2024), explicitly described the massacre as an “act of armed resistance,” rejecting its classification as terrorism or antisemitism and situating it within a broader struggle against colonial domination. This rhetorical shift displaces agency from perpetrators toward historical structures, recoding intentional mass violence as a structurally determined response.

- Delegitimizing Victims through Complicity and “Settler” Coding

Another common strategy involved stripping Israeli victims of civilian status by portraying them as complicit in systemic injustice. A statement issued by Palestine solidarity groups at Harvard on October 9, 2023, declared Israel “entirely responsible for all unfolding violence” (Hill & Orakwue, 2023), thereby erasing the distinction between civilians murdered on October 7 and state institutions. Such rhetorical moves collapse the civilian/combatant boundary and delegitimize empathy toward victims.

- Performative Solidarity and Virtue Signaling

A third pattern emphasized solidarity as ritual performance. On October 11, 2023, the Chicago branch of Black Lives Matter published (and later deleted) a graphic depicting a paraglider with a Palestinian flag—an explicit reference to the October 7 method of attack—circulated as a symbol of support (Center of Extremism, 2023). Online, pre-packaged graphics and binary slogans such as “Silence is violence” spread within hours of the massacre. In such cases, empathy functioned as symbolic capital to signal group belonging.

- Framing Israel’s Response as Genocide

The most significant discursive move was the immediate framing of Israel’s military response as “genocide.” On October 13, 2023, Holocaust and Genocide Studies scholar Raz Segal described the events as a “textbook case of genocide” (Segal, 2023), a formulation that quickly circulated through activist and academic networks. The term “genocide,” used as a maximalist framing device, stripped Israel of any claim to self-defense and completed the inversion in which the October 7 atrocities vanished from the frame while Israel alone was positioned as the ultimate perpetrator.

Discussion

The findings above identified the dominant discursive patterns; this Discussion interprets their broader significance. It shows how language, memory, and affects converge to erode universal moral standards and how these dynamics are strategically exploited within the field of cognitive warfare.

- Analytical Mechanisms: Language as Identity and Memory as a Weapon

From a Critical Discourse Analysis perspective, linguistic choices themselves reveal the moral architecture of a discourse. Terms such as “genocide” or “resistance” function as identity markers, signaling moral alignment within a polarized field and transforming language into a vector of belonging. This mechanism contributes to what discourse theorists describe as the construction of a collective ethos—a shared discursive identity uniting speakers through common values and emotional orientations (Amossy, 2010). In the progressive field examined here, this ethos assumes the moralized form of a “community of the righteous,” in which moral credibility rests not on factual accuracy but on affective conformity. Through this process, empathy ceases to be a universal moral faculty and becomes a marker of group legitimacy.

The rhetorical move to frame Israel’s response as “genocide” is the ultimate example of this mechanism, and it did not emerge in isolation. Long before October 7, the accusation of “genocide against the Palestinians” had functioned as a recurring motif in anti-Zionist discourse, operating in tandem with the trope of Israel’s nazification (Taguieff, 2002; Wistrich, 2012). Both draw upon the symbolic reversal of the Holocaust: the descendants of its victims are cast as their moral heirs-turned-perpetrators, while Palestinians are positioned as the “new Jews.” This dynamic exemplifies what Chaumont (1997) calls competitive victimhood, in which moral legitimacy depends on occupying the highest rank in the hierarchy of suffering. It is a powerful illustration of what historian Henry Rousso (1990) identified as a “syndrome” of memory—a “past that will not pass” (un passé qui ne passe pas) which ceases to be history and becomes an obsessive and infinitely malleable, moral script for the present.

By conflating Israel with Nazism and Gaza with a concentration camp, the rhetoric transforms moral outrage into a performative identity statement—an act of belonging within this “community of the righteous” defined by its opposition to Israel.

- The Erosion of Universal Standards

From the Enlightenment to the post–World War II human rights regime, dignity, liberty, and equality were framed as universal and non-negotiable. Yet after October 7, rights and empathy were redistributed along identity lines: perpetrators coded as “oppressed” were granted legitimacy, while victims labeled “colonial” were stripped of theirs. This inversion undermines the very premise of human rights: if dignity depends on identity, it is no longer universal but contingent.

Such asymmetry is not new. After the September 11 attacks, some commentators rationalized Al Qaeda’s terrorism as “blowback” against U.S. imperialism. In the 1970s, segments of the European radical left romanticized groups such as the Red Brigades or the Red Army Faction (RAF) as authentic expressions of revolutionary struggle, minimizing their violence against civilians. Following the Charlie Hebdo and Bataclan attacks in France, a similar pattern appeared within certain activist and intellectual circles: jihadist violence was contextualized as the product of marginalization, while victims were at times dismissed as complicit in “provocation.” In each case, the targeting of civilians was reframed as structurally determined rather than morally accountable, and empathy was redistributed according to identity-based categories rather than conduct. Violence was excused when committed by actors cast as oppressed, while democratic states were held to standards so absolute that their own suffering was delegitimized.

This dynamic finds its contemporary political expression in what some analysts call the “Red-Green alliance,” where certain far-left (Red) and Islamist (Green) movements converge around a shared anti-imperialist and anti-Western narrative. A key manifestation of this alliance is the “Palestinization” of a segment of progressive identity, where the Palestinian cause is elevated from a political issue to the primary marker of moral and political belonging. This centrality, which often recodes the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as the symbolic epicenter of all global injustices, helps explain why solidarity can become a pre-packaged identity ritual rather than a nuanced response to specific events (Taguieff, 2002).

- Israel as a Paradigm: Implications for Liberal Democracies

For Israel, the weaponization of empathy constitutes a direct strategic liability. October 7 was reframed by some actors as colonial resistance, undermining Israel’s legitimacy and recasting its self-defense as aggression. Delegitimization campaigns by hostile states and transnational movements exploit this discursive environment, leveraging progressive guilt and solidarity with the “oppressed” while erasing universal principles that would otherwise condemn terrorism.

This dynamic demonstrates how empathy itself becomes a weapon in information warfare. By inverting roles of victims and perpetrators, hostile narratives manipulate Western audiences, influence policy debates, and weaken Israel’s ability to sustain international support. October 7 was thus not only a physical assault but also a discursive attack on Israel’s legitimacy.

This vulnerability, however, is not unique to Israel. Other democracies face similar risks when adversaries exploit narratives of victimhood. The 9/11 attacks, European jihadist terrorism, and Cold War–era justifications of left-wing extremism all illustrate the same mechanism: violence reframed as resistance, empathy redistributed along identity lines.

The collapse of universality produces a broader loss of moral clarity. Democracies that excuse violence as resistance undermine both domestic resilience and international credibility. Externally, disinformation thrives when political and intellectual elites embrace relativism. Internally, double standards erode trust in institutions, fuel disillusionment among citizens, and weaken cohesion.

Israel thus represents both a unique and paradigmatic case. Its circumstances are singular, yet the dynamics observed—delegitimization of victims, normalization of violence, and moral double standards—recur across democracies. Israel is therefore not only defending its own legitimacy but also serving as a test case for whether universalism can survive as the foundation of democratic order.

- Cognitive Security as the New Battlespace

This entire process is a textbook example of cognitive warfare. Cognitive warfare refers to the deliberate targeting of perception, judgment, and emotion as operational domains. Unlike classical propaganda, it exploits pre-existing beliefs and moral reflexes rather than fabricating falsehoods. The objective is to shape collective meaning itself — to make certain interpretations socially and morally dominant. In this sense, the manipulation of empathy becomes a strategic instrument: it shifts moral perception before facts are even debated, pre-empting rational deliberation.

The weaponization of empathy does not operate through conventional disinformation, but through a far more sophisticated exploitation of a society's pre-existing ideological vulnerabilities. Hostile actors understand that they do not need to systematically invent falsehoods when they can amplify and accelerate a genuine collapse of universal and shared principles from within.

This strategy is not limited to manipulating Western discourse. A parallel can be seen in the documented influencer operations conducted by the Iranian regime, which have targeted the Israeli public on social media in recent years with the goal of deepening internal divisions and sowing societal chaos. By amplifying polarizing content related to political debates, judicial reforms, or religious-secular tensions, these campaigns aimed to erode national resilience from the inside.

Whether by exploiting postcolonial guilt in Western academia or political friction within Israel, the underlying strategic goal is identical: to erode social cohesion, paralyze political will, and dismantle the normative foundations of democratic legitimacy. This aligns with doctrines of hybrid warfare where the goal is to manipulate an adversary into voluntarily making self-defeating decisions. Consequently, defending against this multifaceted threat requires a robust national cognitive security strategy aimed at reinforcing the shared values that serve as a society’s immune system against such narrative attacks.

Policy Recommendations: Communication Strategy Grounded in Universal Values

The findings of this study reveal that selective empathy, when detached from universal principles, is a strategic liability. Israel and other democracies confronted with narrative warfare must therefore adopt communication strategies that both defend legitimacy and proactively reaffirm universality. These strategies should operate along three complementary axes: offensive communication, defensive communication, and strategic framing.

- Offensive Communication: Anchoring Israel in Universal Democratic Values

Selective empathy corrodes legitimacy when moral claims are framed in identity-based terms. Findings suggest that democracies, and Israel in particular, should consistently present themselves as part of the liberal-democratic family, grounded in shared principles such as liberty, equality, and the rule of law.

- Democratic Norms as Strategic Anchors: Political speeches, media engagements, and diplomatic outreach should explicitly highlight Israel’s adherence to democratic values such as judicial independence, civil rights protections, and minority representation. A state’s legitimacy and influence are significantly enhanced when its values are perceived as attractive and aligned with universal norms, a core component of “soft power” (Nye, 2004).

- Providing Concrete Evidence of Universalism in Practice: Abstract appeals to democracy gain strength when supported by tangible examples—for instance, humanitarian aid operations, Supreme Court rulings protecting minority rights, or contributions to global health and technology. Evidence-based communication strengthens credibility and reduces perceptions of propaganda.

- Positioning Israel as a Contributor to Global Goods: Innovations in medicine, disaster relief, and environmental management should be framed as contributions to humanity. This framing aligns with theories of “public diplomacy as global public goods provision,” which argue that states enhance legitimacy by emphasizing their positive-sum contributions to shared challenges (Cowan & Arsenault, 2008).

- Narrative Framing Grounded in Universality: Communication strategies should stress that selective empathy betrays progressive values themselves by excusing violence and eroding universal human rights. By framing Israel’s struggle as part of the broader defense of liberal democracy, offensive communication situates national security within a compelling strategic narrative designed to shape the normative global order (Miskimmon et al., 2013).

- Build Alliances with Alternative Progressive Voices and Amplify Counter-Narratives: Strategic communication should actively identify, engage, and amplify the voices of those within progressive circles who continue to uphold universal values. Such an alternative critique from within is a potent tool for fracturing the dominant hostile narrative and exposing its intellectual and moral incoherences, thereby seizing the initiative in the normative debate.

- Defensive Communication: Countering Distortions and Selective Empathy

Distorted narratives thrive when left unchallenged. The Findings indicate that democracies must develop rapid, technologically sophisticated, and consistent responses to disinformation and discursive inversions.

- AI-Powered Semantic Monitoring and Rapid Response: Defensive communication can be significantly enhanced through AI-driven semantic monitoring systems. Moving beyond simple keyword detection, these platforms are able to identify, at scale, discursive patterns such as delegitimization of victims or narrative inversion. By analyzing millions of social media posts across multiple languages, they enable the early detection of hostile campaigns before they reach critical mass, thus opening a crucial window for timely intervention. The primary challenge is to preserve credibility and avoid perceptions of state propaganda. To mitigate this risk, outputs should prioritize factual accuracy and transparency, relying heavily on verifiable open-source intelligence and independent validation.

- Consistency in Condemnation: Credibility ultimately depends on applying the same ethical standard to all violence. Condemning violence consistently—regardless of perpetrator identity—reinforces Israel’s claim to universality and preempts accusations of hypocrisy. A publicly available ethical baseline could serve as a reference point across official communications.

- Engaging Independent Validators: Independent academics, legal experts, and humanitarian professionals can provide authoritative contextualization. Their credibility is particularly important when addressing skeptical audiences. Democracies should therefore invest in structured frameworks that facilitate rapid engagement with such validators, while ensuring their independence and transparency.

- Highlighting Systemic Risks: Finally, communications should stress that selective empathy does not only harm Israel but also undermines the universality of human rights and the resilience of liberal democracies more broadly. Comparative references to other democratic contexts (e.g., EU or US cases) can demonstrate that selective empathy erodes moral clarity universally, rather than only in relation to Israel.

- Strategic Framing: Linking Israel’s Struggle to the Liberal-Democratic Order

Israel’s delegitimization should not be treated as an isolated case but as part of a broader erosion of universal values. Strategic communication must therefore emphasize the shared stakes for all democracies.

- Drawing parallels with other democracies: By highlighting similarities between Israel’s security challenges and those faced in Europe or North America (Islamist terrorism, disinformation, radicalization), Israel’s legitimacy can be framed as inseparable from the survival of democratic norms.

- Reaching progressive audiences on their own terms: Progressive values such as equality and dignity can serve as bridges. Communication should stress that selective empathy betrays these values by excusing violence and eroding universality. This approach requires careful navigation, as it risks being dismissed as cynical appropriation if not executed with genuine intellectual honesty and a willingness to differentiate legitimate policy critique from outright delegitimization.

- Differentiating critique from delegitimization: Recognizing legitimate criticism of Israeli policies while firmly rejecting challenges to Israel’s right to exist and to self-determination strengthens intellectual honesty and credibility.

Conclusion

The weaponization of empathy is a core vulnerability for democracies in the cognitive battlespace. The policy recommendations outlined above—grounding offensive communication in universal values, deploying technologically advanced defensive measures, and strategically framing Israel’s struggle within the broader liberal-democratic order—are designed to address this challenge directly. They seek to reclaim empathy as a universal resource, disciplined by truth and moral clarity.

The hijacking of this fundamental human instinct reveals a profound strategic crisis. When morality collapses into partiality, it erodes international legitimacy, constrains freedom of action, and leaves societies exposed to disinformation and illiberalism. For Israel, the stakes are immediate, but the challenge is universal.

This study argues that reclaiming empathy requires both normative clarity and technological adaptation. AI-driven monitoring can detect hostile narratives early, while structured engagement with independent validators can embed universality in practice and strengthen cognitive resilience. From a research perspective, further empirical work could test how communication strategies centered on universal anchors reduce tolerance for narratives that justify violence.

Ultimately, the implication for policymakers in Israel and across the democratic world is clear: cognitive resilience must be treated as a strategic asset, as essential as deterrence or technological superiority. The task is to reaffirm universal values, and to do so with a humility that acknowledges their past failures. A viable universalism for the twenty-first century cannot be a Western inheritance to be imposed; it must emerge as a point of convergence for human reason. The central normative ambition must not resurrect a Eurocentric moral authority, but should reconstruct a minimal shared ground of prohibition that no actor may relativize through identity, grievance, or historical alibi. Without such a baseline, the cognitive field remains vulnerable to those who instrumentalize moral ambiguity for strategic effect.

*Johanna Mamane is a senior analyst and data strategist specializing in antisemitism, radical ideologies, and cognitive security. For nearly a decade, she has led government projects at the intersection of AI, discourse analysis, and narrative warfare to detect and counter online antisemitic discourse. She is currently completing a PhD in Digital Humanities at Sorbonne University and works as a researcher in AI-driven threat intelligence focused on violent extremism.

SOURCES

Afary, J., & Anderson, K. B. (2005). Foucault and the Iranian revolution: Gender and the seductions of Islamism. University of Chicago Press.

Amossy, R. (2010). La présentation de soi: Ethos et identité verbale. Presses Universitaires de France.

Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and simulation [S. F. Glaser, Trans.]. University of Michigan Press. (Original work published 1981).

Batson, C. D. (2011). Altruism in humans. Oxford University Press.

Bherer, M.O. (2024, March 15). Judith Butler, by calling Hamas attacks an act of armed resistance, Judith Butler rekindles controversy on the left. Le Monde. https://tinyurl.com/ywb238be

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power [J. B. Thompson, Ed.; G. Raymond & M. Adamson, Trans.]. Harvard University Press.

Bouvet, L. (2015). L’insécurité culturelle. Fayard.

Center of Extremism. (2023, October 12). Fringe-Left Groups Express Support for Hamas’s Invasion and Brutal Attacks in Israel. ADL. https://tinyurl.com/2udyhwpx

Chaumont, J.M. (1997). La concurrence des victimes: Génocide, identité, reconnaissance. La Découverte.

Cowan, G., & Arsenault, A. (2008). Moving from monologue to dialogue to collaboration: The three layers of public diplomacy. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 10-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716207311863.

Cusset, F. (2008). French theory: How Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze, & Co. transformed the intellectual life of the United States [J. Fort, Trans.]. University of Minnesota Press.

Decety, J., & Lamm, C. (2006). Human empathy through the lens of social neuroscience. The Scientific World Journal, 6, 1146–1163. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2006.221

Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and repetition [P. Patton, Trans.]. Columbia University Press. (Original work published 1968).

Derrida, J. (1976). Of grammatology [G. C. Spivak, Trans.]. Johns Hopkins University Press. (Original work published 1967).

Dutton, D. G., & Painter, S. (1993). The battered woman syndrome: Effects of severity and intermittency of abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 63(4), 614–622. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079474

Fairclough, N. (2010). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972–1977 [C. Gordon, Ed.]. Pantheon.

France. National Assembly (n.d.). The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and other texts [L. Jaume, Ed.; R. Bienvenu, Trans.]. Elysée. (Original work published 1789).

Freud, A. (1992). The ego and the mechanisms of defence [C. Baines, Trans.; Rev. ed.]. Routledge. (Original work published 1936).

Grubbs, J. B., Warmke, B., Tosi, J., James, A. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Moral grandstanding in public discourse: Status-seeking motives as a potential explanatory mechanism in predicting conflict. PLOS ONE, 14(10), e0223749. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223749

Hill, J.S., & Orakwue, N.L. (2023, October 10). Joint statement on the unfolding violence in Israel/Palestine [in the article: Harvard student groups face intense backlash for statement calling Israel ‘entirely responsible’ for Hamas attack]. The Harvard Crimson. https://tinyurl.com/s4fx3d2f

Houellebecq, M. (2015). Soumission. Flammarion.

Kant, I. (1998). Groundwork of the metaphysics of morals [M. J. Gregor, Trans.]. Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1785).

Lyotard, J.-F. (1984). The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge [G. Bennington & B. Massumi, Trans.]. University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published 1979).

Miskimmon, A., O’Loughlin, B., & Roselle, L. (2013). Strategic narratives: Communication, power and the new world order. Routledge.

Nietzsche, F. (2002). Beyond good and evil [J. Norman, Trans.]. Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1886).

Nye, J. S., Jr. (2004). Soft power: The means to success in world politics. Public Affairs.

Oakley, B., Knafo, A., Madhavan, G., & Wilson, D. S. (Eds.). (2012). Pathological altruism. Oxford University Press.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Harvard University Press.

Rousso, H. (1990). Le Syndrome de Vichy: De 1944 à nos jours. Seuil.

Saad, G. (2020). The parasitic mind: How infectious ideas are killing common sense. Regnery Publishing.

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon.

Segal, R. (2023, October 13). A textbook case of genocide. Jewish Currents. https://tinyurl.com/smmytbc9

Spinoza, B. (2002). Ethics. In M.L. Morgan (Ed.), Complete works [S. Shirley, Trans.] (pp. 213-382). Hackett Publishing. (Original work published 1677).

Taguieff, P.A. (2002). La nouvelle judéophobie. Mille et une nuits.

van Dijk, T. A. (2008). Discourse and power. Palgrave Macmillan.

Weber, M. (2004). Politics as a vocation. In D. Owen & T. B. Strong (Eds.), The vocation lectures [R. Livingstone, Trans., pp. 32–94]. Hackett Publishing. (Original work published 1919).

Wistrich, R. S. (2012). From Ambivalence to Betrayal: The Left, the Jews, and Israel. University of Nebraska Press.

[1] This critique concerns subsequent appropriations of postcolonial discourse, rather than Said’s original argument.