Strategic Assessment

China’s relationship with the Gulf countries revolves around energy demand and the new Silk Road strategy, and indeed, Bahraini and Chinese economic interests and geopolitical stakes converge across this new strategy. Nonetheless, a critical question is how close the political and economic relationship between China and the GCC in general, and Bahrain in particular, can become when a strategic alliance with the US covers each of the GCC members. Notwithstanding Western fatigue and the decline of US hegemony in the Middle East, Bahrain and other Gulf states are aware of China’s limitations as a security provider and therefore manage their relationships with the US carefully. Thus, the China’s friendly cooperative relations with the Kingdom are based on shared or mutual complementary commercial interests and Bahrain’s strategic geographical position, and from a policy standpoint, strong Bahrain-China links are expected. However, it should not be concluded that Bahrain has bound itself exclusively to China or that the PRC will pour resources indiscriminately into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Bahrain. Against this background, a geopolitical approach is warranted to analyze the speed and extent to which the BRI will be realized, and its political effect on participating countries from the Persian Gulf.

Keywords: China, Bahrain, Persian Gulf, Belt and Road Initiative, Silk Road strategy

Introduction

In 2019, the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Kingdom of Bahrain celebrated the 30th anniversary of their diplomatic ties, established on April 15, 1989. Over the decades, developing bilateral relations have maintained a favorable momentum (Olimat, 2016). While many have studied China’s ties with the Persian Gulf region, Beijing’s relations with Bahrain remain undocumented. As the Gulf’s smallest and weakest country, researchers have preferred to examine China-Bahrain relations within the rubric of the Gulf states or the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Yet while the PRC’s relations with the Kingdom have been kept out of the limelight and received limited critical attention, they have developed well beyond initial diplomatic and political affairs (Rakhmat, 2014; Olimat, 2016; Qian & Fulton, 2017; Reardon-Anderson, 2018; Young, 2019).

The new Silk Road strategy, put forward in October 2013 by Chinese President Xi Jinping, seeks to connect the PRC to the global market by linking Asia and Europe via a set of land and maritime trade routes. The concept took shape over several years and has become a cornerstone of President Xi’s foreign policy. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become a key theme of bilateral relations, and could also create opportunities for partnerships in the many promising emerging markets between China and countries in the Gulf region (Xuming, 2017). Although the Gulf region is not directly along the BRI trade routes, the Gulf countries have high economic and geopolitical stakes in the PRC’s new Silk Road strategy. Moreover, Bahrain's geopolitical location and economic advantages make it a worthy candidate to fit into the BRI framework.

Indeed, Bahrain and Chinese economic interests and geopolitical stakes converge across the new Silk Road strategy. Since the Kingdom is ideally positioned to play a vital role in China’s BRI, it is essential to examine some of the aspects behind the friendly cooperative relations between the two countries, and especially the synergies between the BRI and Bahrain’s Economic Vision 2030 (BEV2030) to understand the extent of economic engagement and the impact on US dominance in the Gulf. Close scrutiny shows that the PRC’s friendly cooperative relations with the Kingdom of Bahrain are based on shared or mutual complementary commercial interests (integration of the BRI framework and BEV2030) and Bahrain’s strategic geographical position.

China Partnership Diplomacy

The post-Cold War order has provided PRC (a rising power) with a unique strategic opportunity to develop power and influence in the Middle East without facing overt challenges from the United States. "Balancing" against Washington (allying with others against the prevailing threat) during the unipolar era would not advance Beijing’s interests, but at the same time, neither would "bandwagoning" (alignment with the source of danger) or neutrality (Foot, 2006). Dynamic balancing is too risky, and bandwagoning or neutrality is not consistent with Chinese ambitions (Tessman, 2012; Goh, 2005). Instead, Beijing has taken advantage of the relative stability provided by US dominance to develop strong ties with strategically important states in the Middle East (e.g., Iran, Egypt, Turkey, UAE, and Saudi Arabia). These relations have been built mostly on economic foundations, but as they become increasingly multifaceted, there is a corresponding growth of strategic considerations.

Beijing has had to build a regional presence that does not alienate the US or any Middle East states while pursuing its interests. Chinese diplomacy has facilitated a methodical buildup of economic relations, while the US security umbrella provides a low-cost entry into the region. Beginning with trade, economic ties became increasingly multifaceted and sophisticated, incorporating finance and investment. The relationships with the Middle East states (e.g., Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar) have since progressed beyond the economic to include political and security objectives, but have consistently allowed China the flexibility of being everyone’s friend in the competitive regional environment (Fulton, 2019a).

In recent years, partnership diplomacy has become a primary foreign policy tool for the Chinese government. Since the end of the Cold War, the number of partnerships has steadily increased, and PRC has established partnerships with 78 countries and five regional organizations (African Union, Arab Union, ASEAN, CELAC, and EU), which is 45 percent of the 174 countries that have formal diplomatic ties with China. In addition to its comprehensiveness, the network also consists of different stratifications, from ordinary partnership to a comprehensive strategic partnership (Quan & Min, 2019).

China’s partnership diplomacy includes a scale of relations, ranging from a friendly cooperative partnership at the bottom to a comprehensive strategic partnership at the high end (Su, 2000). Each of the five categories of relations features specific priorities, signaling the level of importance Beijing attaches to that state. China’s levels of strategic partnership diplomacy are (from highest to lowest): comprehensive strategic partnership (全面战略伙伴关系) involves the full pursuit of cooperation and development on regional and international affairs. Strategic partnership (战略伙伴关系) coordinates more closely on regional and international affairs, including military. Comprehensive cooperative partnership (全面合作伙伴关系) maintains the momentum of high-level exchanges, enhanced contacts at various levels, and increased mutual understanding on issues of common interest. Cooperative partnership (合作夥伴關係) develops cooperation on bilateral issues, based on mutual respect and benefit. Friendly cooperative partnership (友好合作关) strengthens cooperation on bilateral issues such as trade (“Quick Guide to China’s Diplomatic Levels,” 2016).

In the Middle East, China partnership diplomacy includes seven relationships, spread across the region, that fall into three broad categories in line with their importance. The first category comprises comprehensive strategic partnerships with Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. The second covers strategic partnerships with Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar. The third comprises friendly cooperative partnerships with the region’s smaller states: Bahrain, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen.

The past two decades have seen substantial changes in the global economy and geopolitical trends, with China's rise on the global stage. These developments create new opportunities for the Gulf countries as they look to diversify their economies, increase trade, and seek investment opportunities in emerging markets; this includes efforts such as forging strategic partnerships with China to promote the BRI and to incorporate it into their national development plans (Young, 2019). This reflects a growing drive among the Gulf states to benefit from the favorable business conditions in China, as well as Beijing's expertise and experience in its rapid path to economic development (Oxford Business Group, 2019).

The Gulf countries have strongly embraced and benefited from a network of cooperation with China in various investment and infrastructure projects and other fields. Hence, they have much to gain from the realization of the Belt and Road vision, as the project aims to enhance the PRC’s diplomatic and economic relations with countries that maintain a positive view of Beijing’s global economic and political ascendancy, and can provide the energy resources that it needs to fuel its economy (Cafiero & Wagner, 2017).

In the wake of Arab uprisings and the civil wars, the Gulf countries were pressured to rebuild their economy or boost economic growth to maintain social stability. To this end, they have actively rolled out plans for long-term development for reconstruction and encouraging economic growth, and comprehensive and upgraded Chinese engagement provides the impetus for it (Young, 2019). In this way, there is a common interest for PRC and the Middle East countries to integrate and synergize the new Silk Road strategy with major initiatives (e.g., Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, UAE’s Vision 2021, and others) of future-oriented reforms for national rejuvenation (Cui, 2015).

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

PRC's most significant 21st century diplomatic and economic activity is the launching of the Silk Road initiative. The BRI is the sprawling framework of trade and commercial ties between China and various world regions that have become the flagship foreign policy of the Xi administration. The BRI seeks primarily to open up new markets and secure global supply chains to help generate sustained Chinese economic growth, and thereby contribute to social stability (Watanabe, 2019).

The BRI, the most ambitious geo-economic vision in recent history, has a maritime and land-based component: the maritime element is the 21st century Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI), and the land-based equivalent is the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB). The different sub-branches of the SREB (a series of land-based infrastructure projects, including roads, railways, and pipelines) and the MSRI (comprising ports and coastal development) would create a multi-national network connecting China to Europe and Africa via the Middle East. This is intended to facilitate trade, improve access to foreign energy resources, and give the PRC access to new markets (Xinhua, 2017).

The BRI's geographic scope is continually expanding, covering more than 123 countries and 29 international organizations along six main economic corridors: the New Eurasian Land Bridge; the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor; the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor; the Bangladesh-China-Myanmar Economic Corridor; the China Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor, and the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor. The BRI covers two-thirds of the world’s population, 40 percent of global GNP, and an estimated 75 percent of known energy reserves (Rolland, 2019). The exact total cost of the initiative is not known but according to some estimates, $8 trillion will be invested (Hoh, 2019).

The Persian Gulf and the BRI

China’s relationship with the Gulf countries revolves around energy demand and the new Silk Road initiative. Energy is at the heart of the growing links between PRC and the Persian Gulf, which centers on the crude oil and petrochemical industries, although it extends to other commodities. Beijing’s dependence on crude oil imports from the Gulf, a leading oil-producing region, has increased gradually since 1993 when it became a net importer of oil (Yetiv & Lu, 2007).

As the world's largest consumer of energy overall and the second-largest importer of crude oil, safeguarding a stable flow of crude oil from the region is a paramount concern (Zambelis, 2015). In 2019, roughly half (44.8 percent) of Chinese imported crude oil originated from just nine Middle East nations, and six Gulf states were among the top 15 crude oil suppliers to Beijing (Workman, 2020). Although China is trying to diversify its energy supplies from the Gulf, the most proximate source of oil, it will remain dependent on the Gulf for years to come.

The Gulf countries are important key partners and will play significant roles in the successful implementation of the BRI due to their geostrategic location, energy reserve, and the fast and steady growth of the regional economy, with its rapid expansion of the market for consumer and merchandise goods. China can be a major supplier of these markets.

However, the BRI has become the main focus of strategic and economic engagement between the PRC and Gulf countries. As a strategically important crossroads for trade routes and sea lanes linking Asia to Europe and Africa, the Gulf region is vital to the future of the BRI, which is designed to position the PRC at the center of global trade networks. This means the Gulf region will serve as a hub of the two routes, entailing many added economic benefits. Furthermore, Gulf countries could benefit not only from the BRI’s focus on improved transportation across Eurasia, but also from exports to Asia that avoid the Strait of Hormuz's bottlenecks in favor of the greater affluence and stability in Central Asia (Chaziza, 2020). Thus, the Gulf countries are important key partners and will play significant roles in the successful implementation of the BRI due to their geostrategic location, energy reserve, and the fast and steady growth of the regional economy, with its rapid expansion of the market for consumer and merchandise goods. China can be a major supplier of these markets.

The Importance of Bahrain to China

Bahrain has strategic geopolitical value for the PRC's new Silk Road strategy in comparison to other GCC states. First, the Kingdom is a gateway to the Gulf and one of the key Gulf countries along the new Silk Road route, enabling it to serve as a transportation hub for the region (Olimat, 2016). The island is surrounded by several of the Middle East's large oil fields and commands a strategic position amid the Persian Gulf's shipping lanes, which is the access route for much of the Western world's oil to the open ocean. Bahrain stands at the crossroads of China’s new Silk Road strategy¾an important nexus for trade, investment, science, and cultural exchanges between the Arab and Chinese and the greater Asian, African, and European worlds.

Second, the country benefits from a strategic geographical location on the crossroads of African, Asian, and European markets at the heart of the GCC market, which is currently valued at approximately $2.2 trillion. China has already become the GCC region's largest trading partner; bilateral trade now exceeds $260 billion per year, and is projected to reach $350 billion in the next decade.

Third, Bahrain, known as “the Pearl of the Gulf,” is an important port on the ancient maritime Silk Road. The relationship is deeply rooted in shared history, geography, culture, and economic exchanges.

Fourth, Bahrain is also one of the most modern and dynamic countries within the top-ranking business environment in the Middle East (al-Mukharriq, 2018a; 2018b). Its open and liberal lifestyle, unique market access, world-class regulatory environment, and highly competitive taxation system, combined with the lowest operating costs in the region, high quality of life, and a technologically literate population make the Kingdom an ideal access point for Chinese companies to this $1.5 trillion GCC market (“Bahrain Strengthens Economic Ties with China,” 2018). For Chinese investors seeking business opportunities in the Gulf countries and Africa, Bahrain can be a commercial hub of operations. Bahrain ranks first among the Gulf states in Doing Business 2020, including with the highest number of regulatory reforms. The low cost of doing business in Bahrain is a significant incentive for Chinese and foreign investors seeking a competitive advantage and gateway to large regional markets (World Bank Group, 2019).

Through its strong support for Bahrain’s sovereignty and political stability, the PRC has conveyed an indirect message to Iran that it does not support any instability in the Persian Gulf region. This stance appears to be much appreciated by both Bahrain and Saudi Arabia.

Bahrain also has a unique role as the leading financial hub in the Middle East, for both conventional and Islamic banking. Most of the world's largest banks have operations in Bahrain from which China can do business throughout the Middle East and African region, and indeed, the rest of the world. The Kingdom is the region's banking hub because of its strategic location, its highly qualified labor force, its excellent communications, and not least, its robust regulatory system and reliable Central Bank. In support of the BRI projects, the Kingdom's financial institutions are well placed and capable of working with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the New Silk Road Fund, and the New Development Bank (Alabdulla, 2019).

As the Gulf region becomes increasingly important for Beijing, the Chinese are expected to strengthen their relationship with Bahrain in the coming years. Bahrain could potentially serve as a hub for economic expansion in the Middle East, particularly Saudi Arabia. Finally, Beijing’s position on political stability largely corresponds to that of the Kingdom and Saudi governments. Through its strong support for Bahrain’s sovereignty and political stability, the PRC has conveyed an indirect message to Iran that it does not support any instability in the Persian Gulf region. This stance appears to be much appreciated by both Bahrain and Saudi Arabia (Chaziza, 2020).

Bahrain Economic Vision 2030 (BEV2030)

In 2008 the Kingdom developed a national roadmap for government strategy for the country's future, based on the three guiding principles of sustainability, fairness, and competitiveness. The country’s national plan is to cultivate and diversify the economy by enhancing private sector growth and government investment in infrastructure, affordable housing, and human resources. Bahrain wants to attract foreign investment in five sectors: logistics, light manufacturing, financial services, digital technology, and tourism. The Economic Development Board (EDB) has led a coordinated economic and institutional reform intended to transform Bahrain from a regional pioneer to a global contender. The ultimate aim of the plan is to ensure that every Bahraini household has at least twice as much disposable income, in real terms, by 2030 (Kingdom of Bahrain, 2017).

Bahrain Economic Vision 2030 andthe Belt and Road Initiative

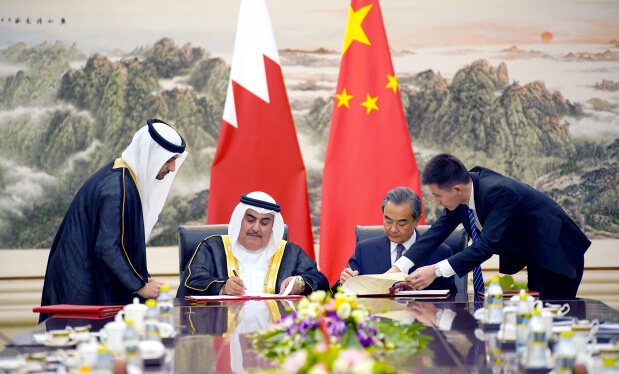

PRC's friendly cooperative relations with Bahrain include four major areas for cooperation within the BRI framework: policy coordination, connectivity, trade and investments, and people-to-people bond. Inevitably, each partner addresses the new Silk Road framework through its own perspective and the consequences for its own national interests and international status. Therefore, in realizing the shared vision, the two countries have very different attitudes (Min, 2015). Nonetheless, BEV2030 and the BRI have converged on a joint economic development path, and their synergetic strategy will bring new opportunities for both partners.In July 2018, Bahrain and China signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to develop the Belt and Road project jointly.

The two sides would continue to firmly support each other on issues concerning each other's core interests and promote pragmatic cooperation across the board under the BRI framework. The Kingdom highly applauds and supports the BRI and stands ready to strengthen all-round cooperation with China and boost bilateral ties. ("China, Bahrain Ink MOU," 2018)

Policy Coordination

China’s friendly cooperative relations with Bahrain are translating into the promotion of bilateral political cooperation; mechanisms for dialogue and consensus-building on global and regional issues; development of shared interests; deepened political trust; and efforts to reach a new consensus on cooperation. These are all important to integrate the BEV2030 into the BRI framework.

Bilateral relations have gathered momentum since the King of Bahrain, Sheikh Hamad bin Isa al-khalifa, visited China in 2013 when he strengthened the bilateral ties and opened new channels of cooperation at several levels (Olimat, 2016). Major agreements were signed in education, health, culture, and investment, which boosted relations and bilateral cooperation (Toumi, 2013). Chinese President Xi Jinping said in talks with King Hamad that Bahrain is an important cooperative partner of China in the Middle East and Gulf region, and "the two countries should be jointly committed to building friendly cooperative relations of long-term stability" (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People's Republic of China, 2013).

The friendly cooperative relations between the two nations have strengthened further over the past years because of Bahrain’s fast-evolving startup ecosystem and the country’s willingness to play a vital role in China’s flagship BRI. According to the Chinese Ambassador to Bahrain, Qi Zhenhong, both countries have become friendly partners of mutual understanding and trust, cooperative partners of the win-win result, and respectable partners learning from each other and deriving mutual benefit. He added that a further strengthening of the friendly cooperative relations between China and Bahrain would not only benefit the two peoples, but also promote strategic cooperation between China and GCC countries, and safeguard regional peace, stability, and prosperity (Qi, 2018).

Connectivity

The facilitation of connectivity is one of the important ways to integrate the BEV2030 into the BRI framework, and the Kingdom would do well to optimize its infrastructural connections to those of the other countries in the BRI framework. This would lead Beijing-Manama to contribute jointly to the development of international transport maritime and overland routes and the creation of an infrastructural network that could gradually connect all the regions in Asia and at specific points in Asia, Africa, and Europe.

In the past, Bahrain traded pearls, dates, and copper, while it imported silk and musk from China. It was a trading outpost along the old Silk Road connecting the Gulf to the world for thousands of years, and traces of the history of this long trading relationship between the two nations can be found at many of the archaeological sites around the Kingdom (Aboukhsaiwan, 2017).

The Kingdom’s strategic location in the heart of the Gulf makes accessibility and entry into any Middle East market (whether by land, sea, or air) fast and economically feasible. The Khalifa Bin Salman Port (KBSP), the premier trans-shipment hub for the Northern Gulf, has enhanced the country’s role as a primary supplier of goods to Saudi Arabia, the region’s largest market. KBSP’s strategic location in the middle of the Gulf, together with its deep-water berths and approach channel that enable it to accept the largest ocean-going container vessels, and its direct overland links to the mainland (Saudi Arabia and Qatar), position the port as a major regional distribution center (Ministry of Transportation and Telecommunications Kingdom of Bahrain, 2019).

Bahrain is also linked to Saudi Arabia, the Gulf’s largest economy, via the 25 km King Fahd Causeway, which is under expansion to handle increased traffic. Since 2014, a 45 km causeway has linked the Kingdom to Qatar, which has the world’s third-largest natural gas reserves and is the second-largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporter (NS Energy, 2019). The link will complete a single trans-Gulf highway, connecting the entire $1.1 trillion Gulf Market, with Bahrain at its center. By 2030, this causeway will also carry a freight railway, thus increasing its capacity. In addition, Bahrain International Airport is undergoing an extensive expansion and modernization program, which is expected to improve the country’s status as a tourist destination and a center for logistics by 2020 (Bahrain Economic Development Board, 2019). Hence, the Kingdom can be considered a great regional transportation hub and a good place for fulfillment centers for Chinese companies that operate along the new Silk Road.

A convergence of interests can forge a basis for cooperation and integration between the BEV2030 and development of the BRI framework by linking these two projects in a way to set up a unified development strategy in the interests of both countries. As Ambassador Qi said,

I do believe under this big picture, the comprehensive cooperation between China and Bahrain is bound to face great and historical opportunity, especially with the integration and implementation of the BRI and BEV2030. (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Kingdom of Bahrain, 2016)

Trade and Investments

Part of PRC’s friendly cooperative relations with Bahrain include attempts to mitigate as much as possible the barriers to free trade, investment, industrial cooperation, and technical and engineering services, to facilitate the integration of BEV2030 within the BRI framework. Measures must be taken by both countries, such as expanding free-trade zones, improving trade structures, seeking new potential areas for trade and improving the trade balance, and devising new initiatives to promote conventional forms of trade (Qian & Fulton, 2017).

Economic relations gained momentum after King Hamad’s visit to China in 2013. Since then, the two partners have launched a large number of commerce and trade investments. For example, in 2019, Bahrain attracted 134 companies with a total investment of $835 million (Sertin, 2020). According to the China Global Investment Tracker, PRC investments and construction in Bahrain from 2013 to 2019 reached $1.4 billion. Most of the Chinese investments are in utilities ($730 million) and real estate ($690 million) in the Kingdom (China Global Investment Tracker, 2020). Bahrain has also attracted some big Chinese companies to invest in the country, including Huawei Technologies, CPIC Abahsain Fiberglass, China Machinery Engineering Corporation, and China International Marine Containers Company (CIMC). For example, in 2009, Huawei moved its headquarters to Bahrain, and it is now creating and accelerating the Kingdom’s 5G mobile network ecosystem (Olimat, 2016).

According to China Customs Statistics (export-import), China-Bahrain trade volume increased to $1.6 billion in 2019, a rise from the $1.3 billion in 2018 (Hong Kong Trade Development Council, 2020). Although Bahrain has fewer natural resources to offer compared to other Gulf states, the country offers PRC a way to access untapped consumer markets for its exports, as well as lucrative investment opportunities. Since Bahrain offers a favorable business environment in the Gulf, leading Chinese companies such as Huawei have established operations in the Kingdom, with attractive policies for foreign direct investment. Currently, about 600 Chinese companies are registered in Bahrain, and the total investment has increased from $50 million to $400 million (Han, 2018).

In addition, the Kingdom is one of the largest financial service centers in the Middle East, with more than 400 well-regulated financial services companies and many financial institutions that have regional headquarters. Investors have a great number of opportunities in Bahrain's mature and sizable business system, and its global, transparent mechanism and strong regulatory system also provide strong support (Han, 2018). In 2010, the Bahrain-China Joint Investment Forum (BCJIF) was formed to facilitate the growth of economic links between the two countries, and 18 Chinese commercial agencies, including the Bank of China, opened operations in Bahrain (al-Masri & Curran, 2019).

In October 2019, Bahrain’s al-Waha Fund invested in Beijing-based MSA Capital―its first investment in a Chinese fund. According to al-Waha, the $250 million Chinese funds have made ten investments across the Gulf region over the past year, facilitating exchanges for Chinese and Bahraini entrepreneurs (CPI Financial, 2019). In November 2019, China’s MSA Capital and al-Salam Bank-Bahrain launched a $50 million venture capital fund, using the Kingdom as a hub to invest in sectors such as e-commerce and financial technology in the Middle East. The fund is the first venture capital project between Chinese and Gulf money. The fund also plans to target big data, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and logistics and networking systems (Barrington, 2019).

In November 2018, a high-level business delegation from Bahrain led by the Capital Governor Sheikh Hisham bin Abdulrahman al-Khalifa and organized by the Bahrain Economic Development Board visited China’s leading commercial centers in cities such as Beijing, Shenzhen, Hebei, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, and elsewhere. Such high-level visits across China emphasized the continuing interest of the Kingdom in fostering deeper economic ties with Beijing, and the spirit of collaboration has grown over the years. These visits also highlight the mutual desire to expand cooperation between the two nations at all levels, from financial services to Information and Communication Technology (ICT), tourism, manufacturing, transportation, and logistics services (StartUp Bahrain, 2018). The agreements and MoUs that were signed represent an important step toward stronger economic ties between China and Bahrain.

People-to-People Bond

China’s friendly cooperative relations with Bahrain, enabling the people of the two countries to bond along with the new Silk Road initiative, are also vital to integrate the BEV2030 within the BRI framework. Extensive cultural and academic exchanges are promoted to win public support for deepening bilateral and multilateral cooperation, providing scholarships, holding yearly cultural events, increasing cooperation in science and technology, and establishing joint laboratory or research international technology transfer centers.

Tourism has become an important aspect of the China-Bahrain friendly cooperative partnership, and both nations have outlined their intention to expand the collaboration in this area in the coming years. PRC’s links with the GCC states have strengthened due to the introduction of additional and direct airline routes, following the strong growth of the Chinese economy and Chinese tourists’ increasing disposable income. According to data from Colliers International published before Arabian Travel Market (ATM) 2019, the number of Chinese tourists traveling to the GCC is expected to increase by 81 percent, from 1.6 million in 2018 to 2.9 million in 2022. The GCC countries currently attract just one percent of China’s total outbound market, but positive trends are expected over the coming years, with forecasts for as many as 400 million tourists in 2030 (Bridge, 2018).

The Chinese tourist arrivals in Bahrain as total arrivals to the GCC grew from 2012 (0.3 percent) to 2016 (0.4 percent), and the annual growth forecasted for Chinese tourist arrivals to the Kingdom is 7 percent. Given the desire of the Bahraini government to implement its Economic Vision 2030, this trend is expected to continue as more and more Chinese travelers seek to reach new, unexplored cities and cultures. The opening of new leisure attractions and business opportunities in the Kingdom and relaxing visa barriers for Chinese travelers to Bahrain will contribute to this trend (Colliers International, 2018).

Cultural cooperation has become another important aspect of the China-Bahrain relations, and both nations have outlined their intention to expand the collaboration in this area in the coming years. In mid-2013, a Chinese painting and calligraphy exhibition, hosted by the China International Culture Communication Center, was held in Bahrain, featuring over 70 works from more than 30 renowned contemporary Chinese artists. The Kingdom also participated in China’s Arabic Arts Festival in 2014, a momentous event to improve understanding between Chinese and Arab people (“Bahrain Takes Part in Arab Arts Festival in China,” 2014). In 2016, China and Bahrain signed a Memorandum of Understanding on the establishment of a Chinese cultural center (Li, 2017). In 2018, Bahrain also participated in the Fourth Arabic Arts Festival in Chengdu that shows the latest achievements of cultural exchanges and cooperation between the two states within the framework of the BRI (Gen, 2018).

Linguistic cooperation is another important aspect of the PRC-Bahrain friendly cooperative relations. In 54 countries involved in the BRI, there are 153 Confucius Institutes and 149 primary and high-school Confucius Classrooms (Huang, 2018). There are eighteen Confucius Institutes and three Confucius Classrooms in the Middle East, including one in Bahrain (Confucius Institute Headquarters, 2020). In April 2014, PRC established the Confucius Institute at the University of Bahrain in collaboration with Shanghai University, which is dedicated to promoting the Chinese language and culture in Bahrain and furthering the understanding of contemporary China (University of Bahrain, 2016).

In education, the Chinese Government Scholarship Program (Bahrain) offers five full scholarships annually for Bahraini students to study abroad in China. The program was founded by China’s Ministry of Education and aimed to increase mutual understanding between the two nations (Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the Kingdom of Bahrain, 2019). According to the Chinese embassy in Bahrain, a few dozen Bahraini students have studied at different universities across China over the past decade. A strong focus on tourism, culture, and education is set to strengthen the bonds of friendly cooperation between the two nations (Rakhmat, 2014).

China-Bahrain Relations and the Impact on US Dominance

Since the 19th century, the Persian Gulf has been one of the most strategically important regions in the global competition for power, for two reasons: for the great sea powers not to allow the Eurasian land power access to the ports in the Gulf (and later to gain control of the oil resources), and for the vast energy resources. The unipolar international order that emerged following the end of the Cold War fundamentally shaped Washington’s dominance in the Gulf. The United States established a regional security architecture that maintained the status quo it favored, and other foreign powers had to either work within that framework or challenge it (Fulton, 2019a). Historically American hegemony across the Middle East has been expressed by its capacity to transform or create major geopolitical crises, shape the behavior of regional states, and when necessary, reconfigure the domestic balance of power between local governments and societies (Yom, 2020).

The Gulf countries, including Bahrain, have started seeking ways to invest in stronger ties with the PRC and other powers, to strengthen their position in an increasingly tenuous geopolitical balance of power. Some are determined to preserve their strategic alliance with the US, but also seek themselves

In the past two decades, substantial changes have been seen in the global economy and geopolitical trends, with the rise of the PRC on the global and regional stages. These developments create new opportunities for the Gulf countries, and Bahrain among them, as they look to diversify or rebuild their economies, increase trade, and seek investment opportunities in emerging markets. They also want to promote the BRI and incorporate it into their national development plan or economic challenges. This is a growing trend among the Gulf countries that want to benefit from China’s favorable business conditions, expertise, and experience in its rapid economic development (Chaziza, 2019).

The relative decline of US hegemony and power in the Persian Gulf and the emergence of a rising China that seeks significant roles in the region might affect power balance stability (Layne, 2018). In this context, the Gulf countries, including Bahrain, have started seeking ways to invest in stronger ties with the PRC and other powers, to strengthen their position in an increasingly tenuous geopolitical balance of power. Some of the Gulf countries are determined to preserve their strategic alliance with the US, but also seek to protect themselves against the threats emanating from regional crises or power competition to guarantee their security (Henderson, 2014).

The PRC recognizes that many Gulf countries, including Bahrain, are distancing themselves politically from the US. Engaging in a new style of relations with China (going from regular partnership to a comprehensive strategic partnership), an economic power free of a historical past as an aggressor in the Gulf and one of the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, offers the Gulf countries a bargaining chip with the US (Chaziza, 2019).

China has significantly increased its economic, political, and—to a lesser extent—security footprint in the region, becoming the biggest trade partner and external investor for many Gulf countries. While it is still a relative newcomer to the region and is extremely cautious in its approach to local political and security challenges, Beijing has been propelled to increase its engagement with the Persian Gulf due to its growing economic presence (Fulton, 2019a). This in turn is likely to pull it into a broader engagement with the region in ways that could significantly affect American interests. Many countries in the Gulf, including Bahrain, have longstanding defense ties and close alliance with the United States. However, some of these US allies, most notably the UAE and Saudi Arabia, have signed comprehensive strategic partnership agreements with China.

Indeed, US-Bahrain ties have deepened over the past four decades as the Gulf region has become highly volatile. The Kingdom plays a key role in regional security architecture and is a vital US partner in defense initiatives. Bahrain hosts the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet and participates in US-led military coalitions, including the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS. Bahraini forces have supported the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan, providing perimeter security at a military base. The Kingdom has received the preferential status for arms procurement from the US since 1987, and it was the first Arab state to lead a Coalition Task Force patrolling the Gulf and has supported the coalition counter-piracy mission with the deployment of its flagship. The US designated Bahrain a “major non-NATO ally” in 2002, which qualifies the Kingdom to purchase certain US arms, receive excess defense articles, and engage in defense research cooperation (US Department of State, 2018). The two nations extended the defense cooperation agreement for an unspecified period during the King’s visit to Washington in November 2017.

As part of its relations with the US, Bahrain has long seen its security-related purchases from the US, and to a lesser extent other Western countries, as a form of insurance. Not surprisingly, about 85 percent of its weapons come from the US. Under the Obama administration, the US withheld some arms purchases from Bahrain (related to Bahrain’s human rights record) following the 2011 uprisings, and publicly chastised the regime in 2016. In 2017, the Trump administration dropped human rights conditions for arms sales, though some restrictions remain on weapons used for crowd control.

Given that security procurement is a critical component of Bahrain’s survival strategy, the country will fight back with threats, either to impose restrictions on the sale of Western weapons or to buy weapons from other suppliers, especially Russia and China. For instance, when Congress froze a sale of small arms to Bahrain in 2011, the monarchy bought small arms elsewhere. Nonetheless, the Kingdom does not have a viable external protector aside from the US: neither China nor Russia at this time has the willingness or capability to take on that role (Vittori, 2019).

In the past years, US-Bahrain economic relations have expanded, even though Washington buys virtually no oil from Bahrain. US imports from the Kingdom include fertilizers, aluminum, textiles, apparel, and organic chemicals. More than 200 American companies operate in the country, and Amazon Web Services is slated to open its first regional headquarters in Bahrain. According to the United States Census Bureau, US goods and services trade with Bahrain totaled an estimated $2.4 billion in 2019: exports were $1.4 billion, and imports were $1 billion. The US goods and services trade deficit with Bahrain was $363 million in 2019 (United States Census Bureau, 2019).

The Kingdom’s economy has been affected by series of anti-government protests led by the Shia-dominant opposition (which includes some Sunni minority elements) from 2011 until 2014, and by a decline in oil prices. The hydrocarbon exports still account for about 80 percent of government revenues, mostly from oil exports (300,000 barrels per day) from a Saudi field (Abu Safa) that it shares equally with Bahrain. The decline in oil prices from 2014 levels has caused Bahrain to cut subsidies for some fuels and some foodstuffs. Financial difficulties have also contributed to unfulfilled government promises to provide more low-income housing (Katzman, 2020). Bahrain has fewer oil and gas reserves than many of its neighbors in the Gulf, and as such, it is looking to diversify its economy from a hydrocarbons base and attract foreign investment. This is the main reason behind Bahrain's friendly cooperative relations with China.

A critical question is how close the political and economic relationship between China and Bahrain in general and the GCC in particular can become when a strategic alliance with the US covers each of the GCC members. The US security umbrella helped PRC establish itself as a major economic and political power in the region. China has built its presence through strategic hedging—steadily increasing its economic engagement with the Gulf region, establishing relationships with all states there, carefully alienating none, and avoiding policies that would challenge US interests in the region. This approach has created a widespread perception of Beijing as an opportunist that takes advantage of the US security umbrella to focus on its commercial projects while providing a non-viable basis to maintain security and stability in the Gulf.

In the last decade, US hegemony has ebbed due to a combination of factors. The US failure and overstretch in Iraq, public exhaustion; the 2008 financial crisis; and the election of Barack Obama and Donald Trump, who in different ways opposed heavy involvement in the Middle East, prompted more reluctance from the region to embrace ties exclusively with the US . The rise of China and greater interventionism from Middle East states saw the US’s previous dominance further challenged. PRC, meanwhile, has significantly increased its economic and diplomatic engagement, designating the Middle East a “key partner” in its Silk Road initiative, and built a physical presence in Pakistan and Djibouti (Chaziza, 2016, 2018).

China still has a limited drive to challenge the US-led security architecture in the Middle East or play a significant role in regional politics (Lons, 2019). However, with the Gulf states’ perception of US retrenchment from the region and as the architecture of the BRI takes shape, this reservation becomes increasingly challenging to sustain. Beijing’s infrastructure projects complement domestic development programs throughout the region, with its substantial investments, trade, and aid, while the West suffers from Middle East fatigue. Rather than freeriding, China undoubtedly contributes to Middle East development and stability (Fulton, 2019a).

As a rising power, PRC engages with Gulf countries in experimental and preliminary ways that are devoid of a clear strategy. Beijing aims to increase its popularity at home rather than seek a geopolitical rivalry with the US in the Middle East. It does so by maintaining stable, great power relations and expanding its commercial interests across the region. Thus, China avoids direct contests for control with established powers and does not establish military bases in conflict zones. Nor does it seek to establish a sphere of influence in the region. For the moment, Washington remains the indispensable player in the Middle East, and the Trump administration has warned its Middle East partners about the consequences of establishing deeper ties to China (Calabrese, 2019).

In the face of inconsistent policies from the US and with an eye to a future with greater Chinese power and influence, Bahrain and many Gulf states perceive PRC as a useful tool in their strategies to diversify not just economically but also politically at a moment of apparent US retrenchment. The BRI addresses their domestic development concerns, and at the same time, signals PRC’s intention to become more invested in the region.

However, Bahrain and other Gulf states are also aware of China’s limitations as a security provider and are, therefore, carefully managing their relationships with the US (al-Tamimi, 2019). At this stage, it is hard to determine whether this is merely a hedging strategy designed to diversify their extra-regional power partnerships or if it signals the beginning of a realignment that stretches across the Middle East to East Asia. It is clear, however, that PRC will be an engaged partner with a clearly articulated approach to building a more substantial presence in the region.

The partnership between Bahrain and China is poised to continue to grow with its limitations, especially in the security, economic, and geopolitical fields. Beijing understands that while the Kingdom wants to maintain close relations with China, Bahrain would not risk jeopardizing its longstanding ties to the US, its closest ally and viable external protector. The same dilemma applies to the US desire to reduce its commitments in the Middle East. In its global rivalry with China, Washington cannot afford to create the kind of void that China would not be able or willing to fill in the short term. This is a situation and a set of relationships that requires careful management by all parties.

Conclusion

PRC does not seek to directly challenge or replace the US military presence in the Middle East, but is intent on strengthening its own economic interests and protecting its assets in the region. most likely to raise its stakes in the region. There is no doubt that Beijing is a rising power in the Persian Gulf, but that does not mean that it will replace Washington’s dominance and play the role of a net security provider for the Gulf states. PRC does not have the capacity either to be a security provider in the Persian Gulf or to challenge the US. Still, China wields increasing power in the Middle East, and in particular, in the Persian Gulf. Even if the US is still the only external power that can provide a security umbrella in the Persian Gulf, the global balance of power has changed, both due to China’s growing presence and due to the US growing strategic interest in the Pacific and hence lesser involvement in the Persian Gulf. In this respect, the BRI not only promotes global trade and connectivity but also creates an economic system outside Washington’s control.

As the Persian Gulf region becomes increasingly essential for PRC’s new Silk Road strategy, China is expected to strengthen its friendly cooperative relations with Bahrain and other local governments in the coming years.

As the Persian Gulf region becomes increasingly essential for PRC’s new Silk Road strategy, China is expected to strengthen its friendly cooperative relations with Bahrain and other local governments in the coming years. Although Bahrain has fewer natural resources than other Gulf states, the Kingdom offers China a way to access untapped consumer markets for its exports, and lucrative investment opportunities. Bahrain also could potentially serve as a regional hub for economic expansion in the Middle East and a logistics center for the growing PRC-GCC trade flows.

Accordingly, PRC’s friendly cooperative relations with the Kingdom of Bahrain are based on shared or mutual complementary commercial interests (integration of the BRI framework and BEV2030) and Bahrain’s strategic geographical position. PRC's friendly cooperative relations with Bahrain include four major areas for cooperation within the BRI framework: policy coordination, connectivity, trade and investments, and people-to-people bond. BEV2030 and China’s BRI framework have converged on a joint economic development path, and their strategic synergy will bring new opportunities for both sides.

From a policy standpoint, strong Bahrain-China links are expected. However, it should not be concluded that Bahrain has bound itself exclusively to China or that the PRC or Chinese companies will pour resources indiscriminately into the BRI in Bahrain to bring about its full implementation. Thus, a geopolitical approach is warranted to analyze the speed and extent to which the BRI is realized, and its political effect on participating countries from the Persian Gulf.

Bahrainis and Chinese statements and commentaries paint a glowing portrait of the BRI in Bahrain. It helps the desert bloom both literally and figuratively as commerce, investments, and capital funds flow into Bahrain to cultivate and diversify the economy by enhancing private sector growth and government investment in infrastructure. Change occurs, but it remains to be seen if the BRI landscape will be filled in wholly, given the political and economic challenges in the Persian Gulf.

The BRI specifically is shaped by the sheer scale and complexity of many proposed mega-projects. These include turning the Kingdom into a regional transportation hub that presents immense design, construction, and financial challenges, which make it unlikely that megaprojects will advance quickly, if at all. Beyond that, it is unclear if specific projects will actually remain economically viable. It also remains to be seen if Chinese companies have the will and ability to invest or, similarly, whether China will be able and willing to loan the immense sums quoted in the headlines, given current circumstances and some of the problems encountered elsewhere along the BRI. Moreover, while trade between the Gulf countries and the PRC has expanded robustly, the commerce with the Kingdom is still relatively modest and is not expected to change dramatically or match other countries in the region in the coming years. Chinese investments in Bahrain are at an early stage, and it is difficult to assess what will be implemented and what will not.

References

Aboukhsaiwan, O. (2017, February 22). China in Bahrain: Building shared interests. Wamda. https://bit.ly/2RwLPUt

Alabdulla, A. (2019, September 29). Celebrating 30 years of China-Bahrain bilateral ties. Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1165859.shtml

Al-Masri, A., & Curran, K. (2019). Smart technologies and innovation for a sustainable future: Proceedings of the 1st American University in the Emirates International Research Conference¾Dubai, UAE 2017. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019.

Al-Mukharriq, J. (2018a, November 12). A high-level Bahraini delegation is visiting China to further strengthen trade and economic ties. StartUp Bahrain. https://bit.ly/2FWGIKO

Al-Mukharriq, J. (2018a, November 18). Bahraini delegation inks 8 deals during Shenzhen visit. StartUp Bahrain. https://bit.ly/3hFZlzs

Al-Tamimi, N. (2019, October). The GCC’s China policy: Hedging against uncertainty. In C. Lons (Ed.), China’s great game in the Middle East. The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR). https://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/china_great_game_middle_east.pdf

Arabian Travel Market Series: GCC Source Market China. (2018, January). Colliers International. https://bit.ly/3koB6aW

Business friendly: Investing in Bahrain. (2019). Bahrain Economic Development Board. https://bit.ly/3cpQ3H6

Bahrain strengthens economic ties with China, signs 8 landmark MoUs. (2018, November 19). Asharq al-Awsat. https://bit.ly/2ZLeg5u

Bahrain takes part in Arab arts festival in China. (2014, September 13). Arab Today.https://www.arabstoday.net/en/75/bahrain-takes-part-in-arab-arts-festival-in-china

Bahrain's al Waha invests in China's $250 million MSA capital fund. (2019, October 17).CPI Financial. https://bit.ly/3kn9oeL

Barrington, L. (2019, November 20). China-Bahrain venture fund targets Middle East tech market. Reuters. https://reut.rs/2RyPAZB

Bridge, S. (2018, December 19). Gulf forecast to see 81% rise in Chinese tourists by 2022. Arabian Business. https://bit.ly/2RCcr6w

Cafiero, G., & Wagner, D. (2017, May 24). What the Gulf States think of “One Belt, One Road.” The Diplomat. https://bit.ly/35NjKjU

Calabrese, J. (2019, July 30). The Huawei wars and the 5G revolution in the Gulf. Middle East Institute. https://www.mei.edu/publications/huawei-wars-and-5g-revolution-gulf

Chaziza, M. (2016).China¾Pakistan relationship: A game-changer for the Middle East.Contemporary Review of the Middle East, 3(2), 1-15.

Chaziza, M. (2018).China's military base in Djibouti. Mideast Security and Policy Studies, 153. Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, Bar-Ilan University.

Chaziza, M. (2019). China and the Persian Gulf: The new Silk Road strategy and emerging partnerships. Great Britain: Sussex Academic Press.

Chaziza, M. (2020).China’s Middle East diplomacy: The Belt and Road strategic partnership. Great Britain: Sussex Academic Press.

China, Bahrain ink MOU to promote Belt and Road Initiative. (2018, July 10). Xinhua. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-07/10/c_137312832.htm.

China Global Investment Tracker. (2020). Chinese investments & contracts in Bahrain (2005-2020). American Enterprise Institute. https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/

Confucius Institute Headquarters. (2020). Confucius Institute/Classroom. http://english.hanban.org/node_10971.htm

Cui, S. (2015, August 31). Sino-Gulf relations: From energy to strategic partners. Jewish Policy Center. https://www.jewishpolicycenter.org/2015/08/31/china-gulf-relations/

Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Kingdom of Bahrain. (2016, September 21). Ambassador Qi Zhenhong's speech on the 2016 Chinese National Day reception. http://bh.china-embassy.org/eng/zbgx/t1399255.htm

Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the Kingdom of Bahrain. (2019, January 16). Chinese government scholarship open for application. http://bh.china-embassy.org/eng/xwdt/t1528121.htm

Foot, R. (2006). Chinese strategies in a US-hegemonic global order: Accommodating and hedging. International Affairs, 82(1), 77-94.

Full text: Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative. (2017, Jun 20). Xinhua. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-06/20/c_136380414.htm

Fulton, J. (2019a, March). Friends with benefits: China’s partnership diplomacy in the Gulf. POMEPS Studies 34: Shifting Global Politics and the Middle East. https://pomeps.org/friends-with-benefits-chinas-partnership-diplomacy-in-the-gulf

Fulton, J. (2019a, October). China’s challenge to US dominance in the Middle East. In C. Lons (Ed.), China’s great game in the Middle East. European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR). https://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/china_great_game_middle_east.pdf

Gen, L. (2018, July 16). 4th Arabic Arts Festival Opens. Go Chengdu. https://bit.ly/2EktRRX

Goh, E. (2005). Meeting the China challenge: The United States in Southeast Asian regional security strategies. Washington: East-West Center.

Han, L. (2018, May 30). Bahraini business environment gives it edge. China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/cndy/2018-05/30/content_36295733.htm

Henderson, S. (2014). Understanding the Gulf States. Policy Analysis. Washington Institute for Near East Policy. https://bit.ly/2H0GpyT

Hoh, A. (2019). China's Belt and Road Initiative in Central Asia and the Middle East. Digest of Middle East Studies, 28(2), 241-276.

Hong Kong Trade Development Council. (2020, January 24). China Customs Statistics: Imports and exports by country/region. https://bit.ly/3cgs9xs.

Huang Z. (2018, December 5). 10 new Confucius Institutes lift global total to 548, boosting ties. China Daily. https://bit.ly/3mN3BRR

Katzman, K. (2020, June 26). Bahrain: Unrest, security, and U.S. policy. Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/95-1013.pdf

Kingdom of Bahrain. (2017, September 11). The economic vision 2030. https://bit.ly/32BxRH3

Layne, C. (2018). The US–Chinese power shift and the end of the Pax Americana. International Affairs, 94(1), 89-111.

Lons, C. (Ed.). (2019, October). China’s evolving role in the Middle East. The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR). https://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/china_great_game_middle_east.pdf

Min, Y. (2015). China and competing cooperation in Asia-Pacific: TPP, RCEP, and the New Silk Road. Asian Security, 11(3), 206-224.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. (2013, September 9). Xi Jinping holds talks with King of Bahrain Sheikh Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa stressing to build China-Bahrain friendly cooperative relations of long-term stability. https://bit.ly/32NVE6C

Ministry of Transportation and Telecommunications Kingdom of Bahrain. (2019). Khalifa Bin Salman Port. http://www.transportation.gov.bh/content/khalifa-bin-salman-port

NS Energy. (2019, November 29). Countries with largest natural gas reserves in the Middle East. https://bit.ly/2Ha5t6

Olimat, M. O. (2016). China and the Gulf Cooperation Council countries: Strategic partnership in a changing world. London: Lexington Books.

Oxford Business Group. (2019). Changing times calls for new GCC relations with China, Russia. https://bit.ly/3kBFm73

Qi, Z. (2018, May 9). Join hands to push China-Bahrain relations. Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the Kingdom of Bahrain. http://bh.china-embassy.org/eng/xwdt/t1558049.htm

Qian, X., & Fulton, J. (2017). China-Gulf economic relationship under the “Belt and Road” initiative. Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, 11(3), 12-21.

Quan, L., & Min, Y. (2019). China’s emerging partnership network: What, who, where, when and why. International Trade, Politics and Development, 3(2), 66-81.

Quick guide to China’s diplomatic levels. (2016, January 20). South China Morning Post.https://bit.ly/35Puxdw

Rakhmat, M. Z. (2014, May 22). China and Bahrain: Undocumented growing relations. Fair Observer. https://tinyurl.com/y2s2dzkl

Reardon-Anderson, J. (2018). The red star and the crescent: China and the Middle East. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rolland, N. (2019, April 11). A concise guide to the Belt and Road Initiative. National Bureau of Asian Research. https://www.nbr.org/publication/a-guide-to-the-belt-and-road-initiative/

Sertin, C. (2020, February 10). Bahrain attracts 134 companies investing $835 million in 2019. Oil and Gas Middle East. https://bit.ly/3cfe43u

Su, H. (2000). The “partnership” framework in China’s foreign policy. Shijie Jishi [World Knowledge], 5 [in Chinese].

Tessman, B. F. (2012). System structure and state strategy: Adding hedging to the menu. Security Studies, 21(2), 192-231.

Toumi, H. (2013, September 13). King Hamad’s visit to boost Bahrain-China relations. Gulf News. https://bit.ly/2ZVObRr

United States Census Bureau. (2020, March). 2019: U.S. trade in goods with Bahrain. https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5250.html.

University of Bahrain. (2016). The Confucius Institute at University of Bahrain. https://bit.ly/2FQbpBn

US Department of State. (2018, July 23). U.S. Relations with Bahrain. https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-bahrain/

Vittori, J. (2019, February 26). Bahrain’s fragility and security sector procurement. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://bit.ly/3iQDWoQ

Watanabe, L. (2019, December). The Middle East and China’s Belt and Road Initiative. CSS Analyses in Security Policy no. 254. https://bit.ly/33LUZSD.

Workman, D. (2020, March 31). Top 15 crude oil suppliers to China. World's Top Exports. http://www.worldstopexports.com/top-15-crude-oil-suppliers-to-china/

World Bank Group. (2019, May 1). Doing Business 2020. https://bit.ly/2EpOcFG

Xuming, Q. I. A. N. (2017). The Belt and Road Initiatives and China-GCC relations. International Relations, 5(11), 687-693.

Yetiv, S., & Lu, C. (2007). China, global energy, and the Middle East. Middle East Journal, 61(2), 199-218.

Yom, S. (2020). US foreign policy in the Middle East: The logic of hegemonic retreat. Global Policy, 11(1), 75-83.

Young, K. E. (2019). The Gulf's eastward turn: The logic of Gulf-China economic ties. AEI Paper & Studies. https://bit.ly/3hQ24qb.

Zambelis, C. (2015). China and the quiet kingdom: An assessment of China-Oman relations. China Brief, XV(22), 11-15.