Strategic Assessment

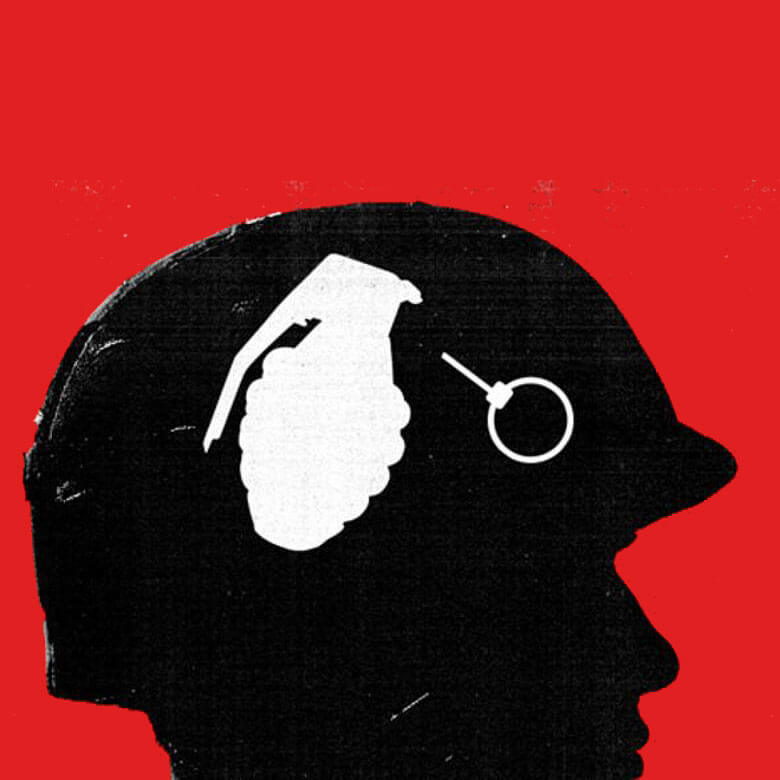

Discourse on the cognitive campaign has increased in recent decades, accompanied by many practical efforts by governments around the world. However, in the excitement surrounding the cognitive campaign, insufficient attention is paid to its inherent fundamental problems and lapses. There is no agreed and systematic definition of the concept, and the result is the inclusion of a large spectrum of phenomena under the broad umbrella of “cognitive campaign.” In addition, there is relatively little study of the outcome of the campaign, and no distinction between elements of limited influence (led by the pretension to change fundamental attitudes among target audiences) and those of greater influence (such as cognitive subversion in the fake news era). This article seeks to organize the methodological dimension of the discourse on the cognitive campaign, while proposing which elements of the campaign are worthy of investment and which are not.

Keywords: cognition, cognitive campaign, cognitive subversion, intelligence

Discourse on the cognitive campaign has increased in recent decades, accompanied by many practical efforts by governments and security agencies around the world, especially in the West. The heightened effort is based on a premise, which is fundamentally correct, that the cognitive campaign is an essential component of the contemporary approach to national security: both in dealing with the threats facing modern countries, and in advances against adversaries from enemy states, to societies and communities on the other side of the border, and to non-state entities, which have been the focus of numerous conflicts around the world in recent decades.

However, in the excitement surrounding

the cognitive campaign, insufficient attention is paid to its inherent fundamental

problems and lapses. First, the extensive focus on the issue is marked by

somewhat limited examination of the practical impact of cognitive efforts and

their achievement of their intended objectives. Second, the discourse on the

subject is fairly chaotic. There is no agreed and systematic definition of the

concept, which results in the inclusion of a large spectrum of phenomena under

the broad umbrella of “cognitive campaign.” In fact, the concept has undergone a

substantial change, and the way it was defined for decades is essentially different

from how it has been described in recent years. Third, the idea of the cognitive

campaign has been glorified considerably. Thus, those who address the issue

sometimes leave the practical and especially the military aspects to one side,

placing at the center of a confrontation issues such as the perception of

reality and the world of images.

This article does not seek to question

or reduce the value of the cognitive campaign; on the contrary. It is a

significant element in the contemporary era, which affects both the fighting

forces, as well as (and perhaps mostly) governments and the public. This paper

attempts to organize the methodological dimension of the discourse on the cognitive

campaign, while shedding critical light on the fundamental problems, most

notably the lack of a clear conceptual framework, a lack of systematic

questioning of effectiveness, and the failure to analyze the profound change

this issue has undergone in recent decades.

The focus here is primarily on Israeli

discourse on the cognitive campaign. Writings, statements, and practical moves

of security officials and political leaders on the subject are addressed; these

are joined by references and analysis of various international cases. The

findings and conclusions drawn from the analysis are therefore of particular

relevance to Israel, yet also have implications for other elements dealing with

the issue, especially in Western countries.

The cognitive campaign is commonly defined as a set of actions and tools through which parties that collaborate in a systemic framework seek to influence or prevent influence on certain target audiences. The purpose of the cognitive campaign is to cause the target audiences to adopt the position of who or what is behind the campaign, so that he/it can advance strategic or operational goals more easily

The cognitive campaign is promoted by

various methods, both overt and covert. Part of the campaign aims to promote

specific goals in the immediate future, while part embraces ambitious

pretensions to change a collective way of thinking. In this context, there is a

distinction between a negative cognitive effort, that is, preventing the

development of unwanted states of cognition, and a positive battle, embodied in

an attempt to produce a desired state of awareness (clearly, the distinction

between "positive" and "negative" depends on its initiator,

since something that is defined by one party as positive is a threat to the

other) (Israeli & Arelle, 2019; and Eisen, 2004, which refers to a United

States Army document defining perception management as “a set of moves whose

purpose is to pass on certain information to foreign knowledge audiences [or

withhold it from them] in order to influence their emotions, intentions, and

desires, influence their assessment of the situation, its objectives, and

conduct of the intelligence arms and leaders on all levels, in a way that

serves the initiator"). In recent years, a new goal has emerged in the

form of an aspiration to plant deep confusion in the opponent's collective

perception, which prevents it from assessing reality accurately. This component

is the key to the concept of the cognitive campaign today.

A thorough review of the many publications in Israel and abroad on the cognitive campaign raises a number of fundamental problems. The numerous aspects and elusive features that have always characterized the concept of cognition appear to seep into the concept of the "cognitive campaign," and call for a profound examination of its content and degree of influence, along with an understanding of the evident gaps or lack of updates. There is a need to distinguish between old components that are part of the cognitive campaign toolbox, many of which have not shown impressive success, and new and different components that have growing impact

The analysis highlights several

problems. The first is eclecticism, such that the

conceptualization of the cognitive campaign is not uniform or clear. Analysis

of various studies shows a cluster of several phenomena, which have a common

denominator, although it is often very general. In this context, four major

efforts are usually evident. The first is cognitive subversion, an element that

is perceived as "new" and influential, and that in the eyes of

societies and governments is considered a major threat given its impact on

public discourse through a number of tools: social networks that produce quick viral

transfer of information and perceptions; the impact on elections (for example

through disruption of voting systems on election day, or the counting of

votes); fake news and cyber warfare (Siman-Tov, Siboni, & Arelle, 2017). The

second effort is an attempt to influence the adversary's cognition, in

particular its perception of reality and the world of beliefs and values of the

wider public in which it operates (one of the "old" components that

raises a serious question, especially with regard to campaigns between Western elements,

including Israel, and forces and communities outside them, especially in the

Middle East). The third effort is psychological warfare (PW) initiatives and intelligence

warfare (IW), i.e., "traditional" fraudulent actions that are usually

accompanied by operational moves; and the fourth effort is information and

diplomacy (Waxman & Cohen, 2019). The various initiatives are promoted with

different methods, the scale of their success is different, and those who

promote them should have a range of skills: communication, networking, and

cyber experts for cognitive subversion, culture and language researchers to

modify cognition; and figures for action, advocacy, and diplomacy in other

areas. In addition, there is a difference between the target audiences of the

various endeavors: most of them are aimed at the "other’s" cognition,

and their basic purpose is to influence its way of thinking and behavior, while

some are focused on domestic society (in an attempt to establish an image of

the campaign underway), or even external factors involved in the campaign

(especially the international arena), whose attitudes and moves regarding the

conflict are of great importance.

A second problem is theoretical overload: the large number of studies on the cognitive campaign reflects a plethora of theoretical conceptualizations and analyses (most of which correspond with theories of crowd psychology, philosophy, and networks research). On the other hand, there are relatively few analyses of concrete examples of threats or moves that illustrate the cognitive campaign, and even fewer on significant successes that reflect its impact. A survey of dozens of studies on the cognitive campaign shows that most of the research discourse today is focused on the efforts of cognitive subversion, or on information and cognition (a phenomenon perceived as a concrete and strategic threat in the Western world, including in Israel), and only a relatively small part of research addresses the effect on the opponent's awareness a topic seen as highly promising a few decades ago, but has proven to be a source of disappointment. In this context, conflicts waged by Western countries against non-Western societies and entities stand out. One of the most notable was the American attempt to instill fundamental cultural change in the Middle East, initiated following September 11, 2001 ("the battle for hearts and minds"), which was especially evident in the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. The limited American goal was to overthrow hostile elements and neutralize their military capabilities, but the broader goal was a profound change in the political and public arena in those countries, which was supposed to turn them into stable democratic nations. This effort found it difficult to bridge fundamental social issues that were not sufficiently understood by the Americans, above all the basic public hostility of the Muslim world toward the United States, as well as the depth of clashing identities and hatred between communities and religions and the strength of sub-national social identities, which made it difficult to bring about any change of attitude toward the goals of the US government.

A third problem concerns innovation.

As many researchers have remarked in recent years, engaging in the cognitive campaign

is not new, but is simply a recent embodiment of the understanding and

endeavors that have existed for thousands of years, and in the modern era have

been more commonly referred to as psychological warfare and intelligence

warfare. However, while in the past most of the moves were focused on deceiving

the opponent, especially at the military (strategic or tactical) level, today's

cognitive campaign is coupled with an ambitious desire for a profound change in

the perception of reality and the thinking patterns of the "other,"

and a strong desire to influence wide audiences. The current intensive

preoccupation with consciousness stems from a number of changes that have taken

place in modern reality, most notably the information revolution and the focus

on social media and technological transformation (in which the rising cognitive

subversion threat is rooted); the dominance of asymmetrical conflicts in the

modern era (from the Vietnam War, through the Soviet campaign in Afghanistan,

to the battles that Israel has conducted in recent decades in the Palestinian

and Lebanese arenas) whose methods and conclusion are devoid of any clarity and

necessitate the engagement in narratives and propaganda; and the increased importance

of publics and communities in modern conflicts (both in the West and beyond,

where other campaigns are underway), which also raises the need to influence

their way of thinking.

The lack of in-depth examination: The practical preoccupation with promoting the cognitive campaign in recent decades has produced relatively limited study as to the success of moves that were promoted, compared to the goals they were supposed to achieve and the resources invested in them (especially regarding moves aimed at initiating a significant cognitive change in communities, which largely failed due to cultural obstacles). As for cognitive subversion, more serious questioning is evident, in part because it is a relatively new and very concrete threat for modern societies (especially democratic societies), which touches on the foundations of their governmental, political, and public existence (here the West is particularly concerned about the Russian effort to influence public discourse and election campaigns, as well as deep disruptions in the fabric of life in times of routine and emergency as a result of cyber efforts). However, research is more limited in areas where the lack of success is more pronounced, most notably in the attempt to influence the broader collective consciousness of the other side, beginning with the American moves in the Middle East two decades ago in an attempt to establish a cultural-consciousness change in the peoples of the region, and Israel's efforts to instill insights and change perceptions and in the public, especially in arenas where it conducted military campaigns, most notably Lebanon and the Palestinian area. (In this context there were measures aimed at "tainting" local leaderships in the eyes of their audiences, beginning with distributing "scent trees" intended to ridicule Hassan Nasrallah in the eyes of the Lebanese public, and the "disclosure" of allegedly embarrassing details about Hamas senior officials such as Yahya Sinwar, alongside an attempt to present positive aspects of Israeli conduct, emphasizing its assistance to the civilian population in those areas). These moves were intended in part to illustrate to the enemy the cost of losing a confrontation, or to improve the basic and negative image of the promoters of the cognitive campaign (the United States and Israel in particular) in the eyes of the "other side." The less presumptuous public diplomacy efforts directed at concrete goals were more successful, as they targeted more focused issues such as exposure of the Iranian nuclear effort and Iran’s involvement in terrorism in the Middle East and the international arena, aimed at exerting international pressure on Tehran, and before that, in the efforts to malign Hamas and Hezbollah in the eyes of the international world in order to legitimize a military campaign against them that inevitably involved both the military and the civilian spaces.

Confusion between the kinetic and subconscious

dimensions: In much

of the research on the cognitive campaign there is often confusion between the

subconscious effort and operational moves that affect the image of reality (and

therefore naturally, also the conduct of human beings and the way they perceive

reality). The cognitive change is largely derived from the intensity of the

kinetic move taken and the circles of influence that it creates. The US bombing

of Hiroshima, Israel’s Operation Focus that started the Six Day War with the

destruction of the Egyptian air force, and Israel’s Operation Defensive Shield in

the West Bank in 2002 were first and foremost practical moves that changed

reality, and only as a by-product led to cognitive changes. In many cases,

without the kinetic move there would have been no cognitive change, and a move

that is focused exclusively on the cognitive dimension, without an accompanying

practical effort, will nearly always have limited impact. Some of the research

is clearly inspired by conflicts with semi-state elements such as Hezbollah

(the Second Lebanon War) or Hamas (three rounds of fighting between Israel and

this organization over the past decade in the Gaza Strip) that cling to the

concept of resistance, al-mukawama (Milstein, 2010). They try to convey an

externalized interpretation, claiming that in spite of the many casualties they

have suffered and their basic inferiority against their enemy (Israel), they

have won the battles by showing patience, denying the enemy victory, and

sometimes even firing the last shot. The discourse promoted by these elements

has helped to establish the widespread claim that there is great importance to

the image of victory, and not only how the battle actually ends. Sometimes this

has led to a simplistic adoption of the other side’s rhetoric, without

attention to the reservations and deep-seated hesitation that has developed

(largely due to the heavy price paid by the public in the campaigns, and the

fears of Hezbollah and Hamas that this will damage their legitimacy at home),

alongside their understanding of the gap between outward propaganda and the

actual situation.

It is hard to shake off the impression that the cognitive campaign is in fact a further expression of the confusion felt by many modern governments and armies in the battles they have faced in recent decades, particularly in the Middle East, South East Asia, and Central Asia. These are conflicts without glory, in which it is very difficult to achieve decisive victories against the enemy, and in fact there is an inability to define the enemy

The situation becomes even more complex when Western armies and regimes find they are facing a combination of civilian and military elements, which creates moral and ethical dilemmas, particularly for Western audiences. This frustrating reality has led to the creation of a collection of concepts to provide Western decision makers, armies, and publics with an interpretation of the conflicts that seeks to explain how they differ from past wars, their limitations, and the possible achievements.

A critical examination of the

comprehensive research and preoccupation with the cognitive campaign shows that

the entire subject is undergoing a process of change, and in fact a dramatic

move away from “old” concepts, which should perhaps be discarded in favor of

“new” ones. It is important to recognize the difference between the various

components of this campaign, understand that some have already failed and

perhaps become irrelevant, and above all, see the effort to effect a cognitive change

in the enemy (which is still energetically promoted by various Western

elements, including Israel). On the other hand, some components are gaining

force and should be at the focus of an updated strategic concept of the cognitive

campaign, first and foremost the effort to influence public discourse (mainly

through the use of online networks) and to interfere with election campaigns.

Contrary to the conclusions of

numerous studies, which state that Western countries should increase their

efforts in the cognitive campaign (beyond the vast amounts of material

resources already invested), it would in fact be more correct to determine what

in the broad basket of components should be classified as concrete threats, as

objectives that can be realized, or as anachronistic means that are pointless

to continue nurturing. And this is even before we start establishing additional

bodies to concentrate or promote the cognitive campaign, which always means the

creation of more bureaucracy and unwieldy work processes.

Cognitive subversion should without doubt be the focus of the effort (Rosner & Siman-Tov, 2018), inter alia by means of developing both defensive (monitoring and neutralizing) and offensive capabilities, as well as through education for digital awareness. In this context there is an obvious need to give the general public insights into ways of dealing with fake news and with hoaxes intended to mislead, confuse, and create panic (Brun & Roitman, 2019)

This has been shown clearly in the last decade in moves made by Russia against its enemies in Eastern Europe, particularly the Ukraine, and in the West, particularly the United States. Presumably this effort will increase in the future, most of all in periods of emergency involving military conflicts, as a way of sowing fear and interfering with communication between governments and the public.

On the other hand, most of the efforts

made so far to bring about a deep cognitive change in the public “on the other

side” have had limited success. The distribution of videos, festival greetings,

and caricatures that mock the enemy’s leaders are popular as entertainment, but

they are generally treated as anecdotes or specific information that was not

familiar in that society. So far they have led to only a slight change in how

those publics perceive the situation, and it appears that they have utterly

failed to change their values and beliefs, particularly with respect to

attitudes to Israel. In this context, there is a range of evidence, from public

opinion polls in the Arab world, through examination of attitudes in the media

and public and online discourse about Israel, to a study of actual behavior in

the “street” with reference to Israel, where it is easy to identify expressions

of basic hostility (which often differ from the government’s position,

particularly in the Gulf states that have recently promoted relations with

Israel, including publicly).

Two decades after the promotion of intensive investment in cognitive campaigns in Israel, while focusing on the establishment of bodies in the security system and in government ministries charged with handling this subject, Israel must conduct a thorough, direct, and honest investigation of its success in this field. Radio and TV channels aimed at the Arab world (a move that began back in the 1950s with the Voice of Israel radio channel in Arabic and the publication of state sponsored Arabic newspapers, and later led to specialized items in Arabic on Israeli television, and the Voice of Israel channel in Farsi) have not yielded insofar as this can be measured in the Arab world a basic cognitive change regarding attitudes toward Israel (based on the metrics mentioned above, which of course are not methodical or completely accurate, but do give a good illustration of the weight of central streams in the Arab space). Other steps taken in recent years, above all the operation of internet sites in Arabic by official entities (such as COGAT the Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories, the IDF Spokesperson’s Unit, and the Foreign Ministry) have achieved only isolated positive reactions (as well as much contempt) but so far do not seem to have led to any deep change in how Israel is perceived by societies in the region that are mainly shaped by local media, social frameworks, educational institutions, and the religious establishment. Until there is a deep and broad change in these elements, there is unlikely to be any real change in public awareness.

The use of online channels in recent

years is not without benefits: they have managed to provide Arab audiences with

alternative information that is generally perceived by them as credible about

issues (including Israel’s actions) that they do not get from other sources. However,

the Israeli effort has not brought about a fundamental change in how Israel is

perceived in the region. Sometimes Israel has praised itself for “changing

awareness” of the other side (mainly in the context of the Palestinian

campaign) or for “cracks in public trust” of their leaders (as was claimed

about Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah), but it appears that the

actual impact is far more limited. If and when there is internal protest and

criticism of those forces, they generally derive from internal processes (such

as the economic situation in Lebanon or government corruption in Iraq last

year) and not because of any Israeli cognitive campaign.

In conclusion, it appears that when

Israel analyzes its moves in the cognitive campaign, it must focus its efforts

on defense against subversion in the shape of fake news, while restricting its

investment and expectations (and the description of successes) with respect to

changing the thinking of societies and population groups. This effort should continue,

since it has importance that could well increase over time, but it is also

necessary to recognize its actual impact. In other words, the cognitive campaign

that Israel should adopt should have more defensive characteristics intended to

prevent damage to the soft underbelly of democracy, and fewer offensive

characteristics intended to change perceptions and values on the other side,

which have proven to have limited influence (excluding more focused moves that

amount to deception, accompanied by tactical or strategic military actions).

In addition, it is necessary to demonstrate caution in attempts to influence awareness on the other side, which could have the opposite effect. An example is the encouragement expressed in Israel for protests in Lebanon, in which the points of dispute are not between supporters and opponents of Israel, and where Israeli support for one side could damage its public image. In another context, it is recommended to avoid confusing success in the creation of perceptions of the price of heavy losses for the enemy, leading to unwillingness to make operational moves (and generally achieved after intense military conflicts, as discernible among Hezbollah and Hamas in the last two decades), and cognitive change an objective that is also directed at the society in which the enemy operates, and which embodies belief in the ability to bring about fundamental changes in how Israel is perceived and the formulation of the “other” party’s basic existential values and principles.

And as always, deeper familiarity on the part of those engaged in the cognitive campaign, headed by intelligence personnel, with the cultural world, language, and history of the object of their research, which has actually declined in recent decades Michael & Dostry, 2017), should always be the main key to more effective and no less important, more realistic moves with respect to attainable objectives, as opposed to unattainable ones (Milstein, 2017). However sharp their intelligence, people who engage in the cognitive campaign without an understanding of the cultural codes and expertise in the language of their targets will have difficulty finding the precise weaknesses or in defining moves that will have real impact. In this context, Shimon Shamir, a scholar on the Middle East and veteran diplomat, noted that “knowledge of the language gives access to content and nuances that are almost impossible to translate. It opens a window onto the world of values and attitudes, wishes, and hopes in the neighboring society in a way that has no substitute” (Shamir, 1985); while Martin Petersen, a former senior CIA official, has stated that for intelligence personnel there is no substitute for familiarity with the language and culture of their research subjects (Petersen, 2003).

***

My thanks to Maj. Gen. (ret.)

Gershon Hacohen, Brig. Gen. (ret.) Yoram Hamo, Brig. Gen. (ret.) Itai Brun, and

Amos Harel for their insights, which helped me to polish the arguments in this

article.

Sources

Ben-Porat, I. (2018, June 26). COGAT

presents: A digital response to the Palestinians. Arutz Sheva [in

Hebrew].

Brun, I., & Roitman, M. (2019).

National security in the era of post-truth and fake news. Tel Aviv: Institute

for National Security Studies. https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/National-Security-in-the-Era-of-Post-Truth-and-Fake-News.pdf

Eisen, M. (2004). Thecognitive

campaign in the post-modern war: Background and conceptualization. In H.

Golan & S. Shay (Eds). Limited conflict (pp. 347-376). Tel Aviv: Maarachot

Israeli, Z. & Arelle, G. (2019). Cognition

and the cognitive campaign: A theoretical viewpoint. In Y. Kuperwasser & D.

Siman-Tov (Eds.). The cognitive campaign: Strategic and intelligence perspectives

(pp. 25-38). Tel Aviv: Institute of National Security Studies, Memorandum 191,

with the Institute for the Research of the Methodology of Intelligence Heritage

Kuperwasser, Y., & Siman-Tov, D.

(2019). The cognitive campaign: Strategic and intelligence perspectives.

Tel Aviv: Institute of National Security Studies, Memorandum 191, with the Institute

for the Research of the Methodology of Intelligence Heritage [in Hebrew].

Michael, K. & Dostry, E. (2017). Human

terrain and cultural intelligence in the test of American and Israeli theaters

of confrontation. Cyber, Intelligence & Security, 1 (2), 53-83.

Milstein, M. (2009). Mukawama: The

challenge of resistance to Israel’s national security concept. Tel Aviv:

Institute for National Security Studies, Memorandum 102 [in Hebrew].

Milstein, M. (2017). “It won’t change…it

has changed, it will change”: The disappearance of in-depth understanding of

the subjects of research from the world of intelligence agencies and its effect

on their abilities and their relevance. Intelligence in Practice, 2,

59-67 [in Hebrew].

Petersen, M. (2003). The challenge for

the political analyst. Political Analysis, 47(1), 51-56.

Rosner, Y., & Siman-Tov, D.

(2018). Russian intervention in the US presidential

elections: The new threat of cognitive subversion. INSS Insight 1031.

Shamir, S. (1985). Study of Arabs and study

of ourselves. In Knowing nearby peoples: How Israel deals with the study of

Arabs and their culture – series of discussions. Jerusalem: Van Leer

Institute in collaboration with The Israel Oriental Society.

Siman-Tov, D., Siboni, G. & Arelle,

G. (2017). Cyber threats to democratic processes. Cyber, Intelligence &

Security, 1(3) December 2017, pp. 51-63.

Waxman, H., & Cohen, D. (2019). Beyond

the network: Diplomacy, cognition, and influence. In Y. Kuperwasser &

D. Siman-Tov (Eds.). The cognitive campaign: Strategic and intelligence

perspectives (pp. 51-60). Tel Aviv: Institute of National Security Studies,

Memorandum 197, with the Institute for the Research of the Methodology of

Intelligence Heritage.