Strategic Assessment

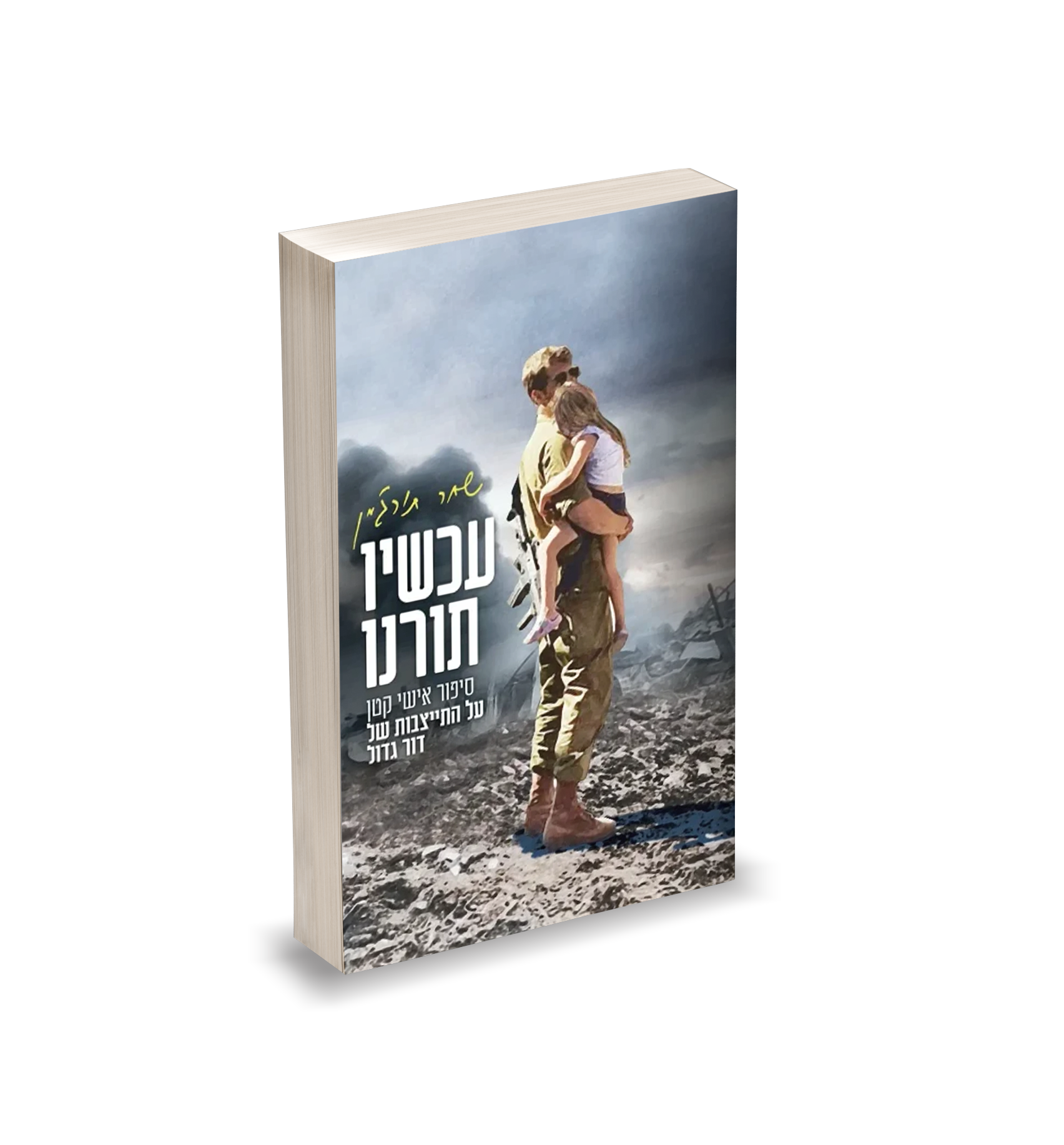

- Book: Now it’s our turn: A small personal story about the shaping of a great generation (In Hebrew)

- By: Shachar Turjeman

- Publisher: Am Oved

- Year: 2025

- pp: 227

Shachar Turjeman has written “a small personal story about the shaping of a great generation,” according to the subtitle of the book, and indeed this is his personal story and that of the platoon he commanded in the Swords of Iron War, first on the Lebanese border and later during the fighting in Gaza, in rehabilitation and maneuvers in Lebanon at the end of 2024. Yet this is not a small story, but a big story about people—reservists who left their homes on October 7, 2023 in order to fight the enemy. The book joins other books published thus far about this war, written by both soldiers and commanders, most of whom are still serving in the reserves, while the war has not yet ended. It seems that some of the books were published after the initial major maneuver that took place in Gaza, such as those by Elkanah Cohen (2024) and Moshe Wistoch (2024)—who recount the story of the fighting that ended in early January 2024, or at the end of December 2023, respectively—while others wrote with an understanding that the intense period of the war was over for them. In the Swords of Iron War, unlike past wars (except for the War of Independence), there have been “waves” of more intense military activity, in both Gaza and Lebanon, so that sometimes the end of a particular wave seems like the end of the war, or at least its active phase, and this of course affects recruitment and the participation of reserve forces in the war, and consequently the fighters and commanders in the reserves who write and publish their stories.

Other kinds of books have been published on this war, giving us insight into the war itself, the people involved and its strategic aspects. There are descriptive accounts and semi-academic studies of the surprise attack of October 7, such as “Iron Swords, Broken Hearts” (2024) by Michael Bar-Zohar, or “The Gaza Division has been Captured” (2024) by Ilan Kfir. These are similar to the books that were published immediately after fighting ended in the Second Lebanon War or Operation Protective Edge, and they seem to hint at a kind of competition to be the first to define the narrative of the particular war or operation. Another genre is the collection of short stories of heroism brought together by an editor, such as “Heroes alone against Hamas” (2024) by Yoav Limor, or “We’re on the way” (2024) by Nachum Avniel. There are books written by residents of the western Negev, such as Hadas Calderon’s “To see the blue sky” (2024) or “Wrapped” (2025), edited by Dalya Robinson, and “Journey back to the home that betrayed” (2024) from Ami Kahane, all reflecting the difficult emotions surrounding the October 7 attack, coping with it and its consequences, and also the rebuilding that followed.

Shachar Turjeman’s book, “Now it’s our turn,” is constructed according to the order of events and is a kind of personal journal, in which he describes the experiences of the engineering reconnaissance platoon (Mahsar) of the Engineering Battalion that he commanded. While describing the experiences of his platoon in the war, he is careful to report not only who did what and when, but also shares with his readers his doubts, thoughts of home and friends, the reasons for his decisions, particularly those that had an effect on his men—or more correctly, his friends in the platoon. The first part of the book deals with the defensive fighting in Lebanon at the start of the war, in which the platoon also initiated engagements as far as was possible. The Mahsar of the Engineering Battalion is a specialized platoon that is able to execute a variety of tasks, and Turjeman wanted his actions to be as meaningful as possible.

At the end of the first part of the book, Turjeman describes his platoon’s move down to the Gaza front, following his request to his commanders. “‘Take heart,’ I said, ‘this evening we’re packing up the platoon and going down to Gaza’” (page 47); Turjeman emphasizes for the reader how he chose to convey to his platoon the importance and significance of his decision to move them to the most active fighting front at that time, and the approval it garnered from his commanders. In the second part of the book, which is twice as long as the first part, we quickly discover that the platoon is a very significant addition to the fighting power in Gaza. Turjeman’s engineering reconnaissance platoon is commanded by the forces operating in Gaza, particularly Division 36, but also Divisions 98, 99, Gaza and even 162. Turjeman continually reminds us that Division 36 is their “home,” but it appears that he became very attached to Division 99 and there they were given numerous missions and excellent cooperation, at least in terms of the number of missions, the feeling that his platoon was needed, the assistance and protection provided as they maneuvered into and out of battle.

Turjeman writes of the temporary truces, the short visits home where he encounters his wife, his children, and also reality. In the chapter headed “A short break and return to sanity” (p. 139) he explains the need for such breaks in wartime, although they only provide momentary sanity because almost immediately he goes back to war. “Unlike the south, in Haifa there was no sense of war […] All the stores and restaurants were open, and even the discounts for soldiers had disappeared in most places” (p. 139). Here Turjeman protests the situation in a country mired in war, but not in equal measure everywhere. It reminds me of my home visits from the security zone in Lebanon in the 1990s; suddenly I encountered completely normal life, just a few kilometers from my military post.

At the end of the second part of the book Turjeman describes an incident from January 8, 2024, in which two fighters from Turjeman’s platoon were killed while four Yahalom soldier and a number of others, including Turjeman himself, were wounded. He describes the course of events prior to the incident: The platoon and Yahalom soldiers had finished laying a number of charges in order to blow up several targets in the Al-Bureij area. A tank that was part of the force securing the action identified enemy forces and fired shells at them, this set off the charges and the soldiers were hit.

A deafening explosion created a shock wave that split the tunnel and threw Eden and David against the concrete wall […] Outside everything was gray. A cloud of destruction and death covered everything […] Neither of us moved. We were covered in soot and blood […] Zinny turned Sagi over and laid him next to me […] He shouted for a tourniquet, saying Sagi was losing blood, and then asked where Akiva and Gavri were (p. 174).

In the third part of the book, Turjeman begins to talk about his injury from this incident. “Apparently I’m a body, apparently that’s how you feel when you’re dead and lying on the ground […] Somebody yells ‘bring tourniquets’” (p. 179). Immediately afterwards he is concerned for his platoon: “Wwwhat about Ddadon? […] And wwwhat about Sssagi? Which Sagi? The famous one? […] Sagi’s been taken to Tel Hashomer” (p. 181). He discovers that two of his soldiers have been killed, others wounded but they’ll recover, some are in other hospitals. He describes the meeting with his wife in the hospital—a moving, inspiring meeting. Although he is unable to attend the funerals, he manages to visit the families during the Shiva (7-day mourning period) and attend the 30-day memorial. He shares his soul-searching regarding his actions, the way he pushed the platoon to take on missions, and wonders if he should have done anything differently. He ultimately describes being at peace with what he did, and is encouraged by the families—of the victims and also his own immediate family—the men of his platoon. A few months later they are called again, this time for maneuvers in Lebanon. Turjeman continues to command the platoon. It seems that his wife is not very happy but the phrase so familiar to so many of us—“there’s nobody else”—is apparently stronger than anything, and the platoon takes part in a maneuver in south Lebanon, in the Avivi area near Maroun el-Ras.

Right at the end of the book is a short chapter entitled “It’s over” (p. 226-227). It’s not clear whether it’s over for the author, because reserve duty continues, but the story ends with this chapter, at least for now. While he longs for days of grace, peace and calm for the Israeli people, it seems that at least at the time of writing this review, May 2025, the war is continuing with varying intensity, the end is still very far away, and the author and his comrades in this excellent patrol platoon will certainly find themselves in a further round of reserve service—perhaps in Syria, in Lebanon or in Gaza.

In the penultimate paragraph Turjeman writes: “For me, writing has become a means of healing, every word was therapeutic, every sentence strengthened my awareness of this complex and painful reality” (p. 226). Indeed many fighters and commanders have written and are writing about this war, their experiences, their dilemmas, their losses, and on how to keep going.

Elkanah Cohen wrote “Personal Account 7.10.23” (2024) and was one of the first to publish a personal journal from the war, which he expanded in some places with discussions of personal dilemmas and conclusions about people, war, and the relationship between them. He was a combat officer in the reserves and describes how his force fought north of Gaza City in the first three months of the maneuver, from October to December 2023.

Hananel Zilberberg has published his own personal journal, “What’s the Link?” (2024), in which he describes the war that he encountered as the reservist liaison officer in the Forward Command Post of Brigade Commander 7 in the war, fighting in Gaza and then in Khan Younis. His book contains a lot of introspection in which he examines his conduct during and before the war in various positions he held before his discharge.

Lishi Tenenbaum’s book is a kind of very detailed journal kept by a tank commander in the reserves, called “The legendary 2B—the story of a tank crew in the Swords of Iron War” (2025). The book gives a great deal of detail about daily activities, showing the reader the lives in war of a very small and intimate team – a tank crew.

In his book “Iron Friendship” (2024), Moshe Wistoch combines his own experiences as a combat soldier in the Alon Reserves Battalion with an account of the whole battalion’s activity in the war, which makes this book different from the others.

Nimrod Palmach wrote “My Brother” (2025), in which he mainly describes how he fought on October 7, and the personal challenges he faces in the recovery that came after, including his treatment or healing, as he prefers to phrase it.

This phenomenon of soldiers and commanders writing about the war, the fighting or the battles in which they took part, and also the processing or healing they undergo afterwards, is not unique to this war. I too wrote a book called “Part of Me Was Left Behind” (2024), about the experiences as a fighter and commander in the security zone in Lebanon in the 1990s, the story of the battle in Wadi Brech that became known as the “Fire of Wadi Saluki,” where I lost five fighters of my platoon. But the main part of my book deals with how I and my immediate environment processed what happened, and this could encourage other commanders to process their experiences of warfare.

I will not survey here all the books written by fighters about the wars in which they participated, but it appears that in recent years there has been more room for this, particularly with the rise of numerous private publishers, and those who provide a professional polish for writers who wish to publish their personal stories. Another reason for the increase in the numbers of soldiers and commanders writing about their experiences is the awareness and openness in Israeli society to the mental dimensions of war, to the way in which experiences of fighting are processed and treated, and thus also to the subject of dealing with post traumatic stress, which emerged strongly in the public consciousness following the case of Itzik Saidian, a Golani fighter in Operation Protective Edge, who set fire to himself in 2021 to protest how the Rehabilitation Division treated those who were mentally damaged.

Shachar Turjeman’s book is just one of the books published and being written by soldiers and commanders in the Swords of Iron War, though it is one of the better ones. Why? Because he stops in many places during the description of events, turns his gaze inwards, to examine his decisions, looking at the people in his platoon—the Engineering Battalion’s patrol platoon family—and listens to them, and in this way enables readers to identify with the situation, to try and understand what it is to be a man in battle, and above all, the commander in battle. Particularly in such a socially and politically polarized time, Turjeman avoids the political discussion of the war and thus allows readers to connect with the story, the experience, the feelings and the dilemmas with no additional “baggage.”

The books of the Swords of Iron War written by soldiers and commanders, the majority reservists, are an important source for learning about the war, and particularly the experiences of the forces on the battlefield and how they conduct themselves. True, there are many reservations surrounding such publications, but the books express the human experiences of their writers as well as the need of fighters and commanders to share and publicize what they went through—a need that as we have noted is becoming stronger in recent years.

These war diaries enable Israeli society to learn directly about the events of the war and the experiences of the people involved, and can thus help to bridge the gaps between those who experience the war personally and those who are not directly involved, at least not on the battlefield. The journals also enable commanders to read the accounts of fighters and commanders of their own generation, and not just those of the past, such as Yoram Yair who wrote “With me from Lebanon” (1990), telling the story of a paratroop brigade in the First Lebanon War (“Peace in Galilee”) in the words of its commander; or Yoni Sitbon who wrote “Under Fire” (2016), about his experiences as a commander in the early 2000s, and particularly in the famous battle fought by Battalion 51 at Binat Jebel in the Second Lebanon War. Wide engagement with books of this kind is always important; how much more so in a time of war.