Publications

INSS Insight No. 1912, November 14, 2024

The election of Donald Trump to the US presidency represents a particularly concerning scenario for Tehran. Despite initial attempts by Iranian official to downplay this development, it is clear that Iran is highly apprehensive about the election results, especially given reports that it had attempted to assassinate Trump and his hawkish stance toward Iran during his first term. Furthermore, Trump’s return to office finds Iran at a critical crossroads. In the short term, it must decide on the timing and nature of its response to Israel’s attack on October 26. In the longer term, Iran faces a choice of whether to pursue appeasement and negotiations or escalate its confrontation with the United States. While dialogue with the incoming administration remains an option, it largely depends on the willingness—however dubious—of Iran’s Supreme Leader Khamenei to moderate his positions and make significant concessions on Iran’s nuclear program. Trump’s election, coupled with Iran’s increasing readiness to take greater risks and the influence of hardliners within its leadership, including the Revolutionary Guards, heightens the danger of a more serious conflict between Iran and the United States.

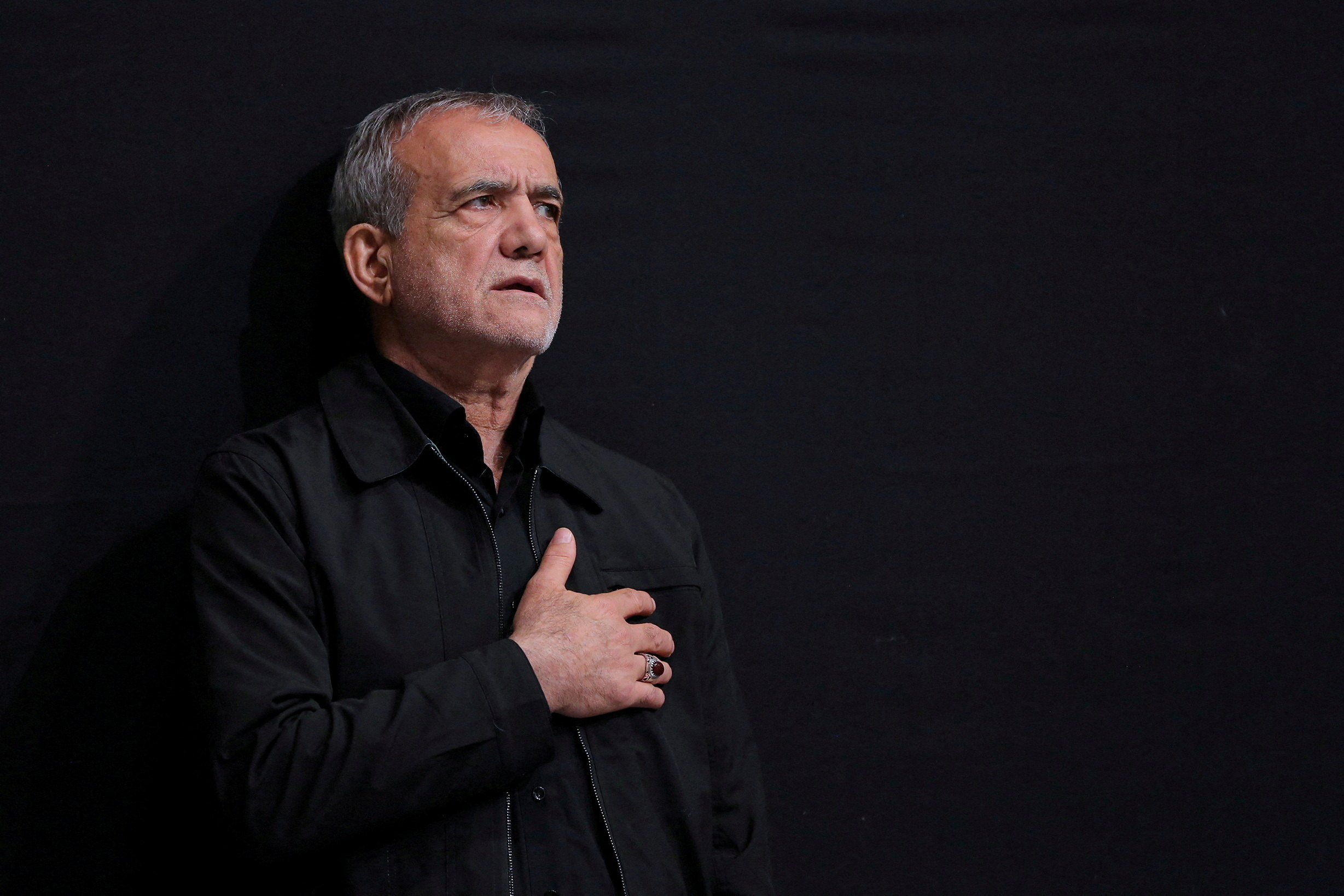

Donald Trump’s election to the presidency of the United States represents the realization of a concerning scenario for Tehran. The initial reactions in Iran reflect a significant attempt to downplay Trump’s re-election. In response to the election results, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian stated that it doesn’t matter who wins, because Iran and its system rely on their own strength and their own people. The Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Esmaeil Baghaei, addressing Trump’s victory, remarked that Iran has faced bitter experiences with the policies of various American administrations and that the election gives the United States an opportunity to correct its past mistakes. He emphasized that Iran would judge the current administration by its actions.

The daily newspaper Kayhan, considered close to the Iranian leader, responded to the election results with an editorial titled “America is the Great Satan—Irrespective of Who Is President.” However, this time, President Trump is moving into the White House amid reports from US intelligence sources that Iran attempted to assassinate him and conducted a social media campaign against him, while senior members of his previous administration require security due to threats to their lives. All this takes place against the backdrop of Trump’s hawkish policies toward Iran during his first term (2016–2020), when the United States withdrew from the nuclear deal in May 2018, imposed maximum economic pressure on Iran, and assassinated Qasem Soleimani, commander of the Revolutionary Guards’ Quds Force, in January 2020. In Tehran, leaders are particularly concerned about the incoming administration’s intention to return to the “maximum pressure” policy aimed at isolating Iran and financially weakening it through severe sanctions, including stricter enforcement of sanctions on Iranian oil sales to China.

The change of government in the United States finds Iran at a significant crossroads. In the short term, it must decide how and when to respond to the Israeli attack on October 26. This dilemma challenged the Iranian leadership even before Trump’s election, and now they face two risky options:

Responding to the Israeli attack, despite significant risks—including the possibility of provoking Israel’s pledged response, which could target Iran’s nuclear program, vital oil facilities, or even trigger American intervention beyond defending Israel.

Refraining from a response, risking further erosion of its deterrence power against Israel and potentially signaling weakness to its regional proxies and domestic support base.

In the broader context and over the longer term, the multi-front regional campaign and direct military confrontation with Israel impose increasing security challenges on Iran and the pro-Iranian axis, which has been severely weakened in this conflict. This occurs at a time when the Islamic Republic is grappling with severe economic turmoil, a profound crisis of regime legitimacy, and preparations for the anticipated succession struggle following the eventual passing of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who is now 86.

It is true that the option for dialogue with the American administration, aimed at lifting sanctions, still exists—a possibility mentioned by the Iranian president at the UN General Assembly last September. During his first term, President Trump expressed readiness to negotiate with Tehran in the fall of 2019 and even indicated a desire to meet with former Iranian President Hassan Rouhani. During his recent campaign, Trump also declared his intention to pursue a new deal with Iran as soon as possible (if his terms are accepted). Additionally, Brian Hook, who managed the Iran portfolio in Trump’s previous administration, recently stated that the new administration was not seeking a regime change in Iran. Furthermore, Tehran remembers that Trump refrained from a military response to Iranian provocations in the Persian Gulf, which included the downing of an American drone in June 2019 and the attack on Saudi Arabian oil facilities in September 2019.

Still, as Trump prepares to return to the White House, Iran faces a different situation than it did at the start of his first presidency in 2016. Since the reimposition of sanctions in 2018, Iran has managed to handle them with some success by reducing its economic dependency on the West and diversifying its sources of revenue and markets. Additionally, closer ties with Russia (primarily in military and security matters) and China (in trade) have bolstered its resilience against the sanctions. Furthermore, the ability of the incoming American administration to exert economic pressure on Iran largely depends on Beijing’s willingness to halt purchases of Iranian oil and, in the case of Russia, on the potential re-evaluation of relations between Washington and Moscow.

Iran’s current position on the nuclear threshold, combined with the ongoing erosion of the International Atomic Energy Agency’s oversight of its nuclear facilities, strengthens its ability to quickly break out to nuclear weapons if a political decision is made. In this context, recent statements within Iran suggest that its nuclear strategy may be under review at the highest levels. Additionally, Iran’s improved relations with its Arab neighbors, particularly Saudi Arabia—marked by the March 2023 agreement to renew diplomatic ties and reinforced by the recent war between Israel and Hamas and Hezbollah—provide Iran with political opportunities that were absent during Trump’s first term.

Nonetheless, Iran currently faces considerable challenges, particularly with growing doubts about its ability to maintain effective deterrence against its primary adversaries, the United States and Israel. These doubts have intensified with the recent weakening of the pro-Iranian axis and Iran’s failure to deter Israel from continuing its campaign against Iran and its proxies, even following two attacks on Israel in mid-April and early October. Unlike Trump’s first term, when Iran primarily faced the repercussions of economic sanctions, particularly from late 2018 onward, this time the American administration has a full term to implement its policy, including increasing pressure on Iran.

Given this reality, Iran must reassess its policies on a range of issues, the most urgent being its response to the recent Israeli attack. Trump’s election to the presidency could push Iran in one of two opposing directions: it might encourage Iran to respond before the new president takes office, based on the assessment that its ability to engage militarily with Israel could become even more limited and risky once Trump assumes power. Conversely, Iran might conclude that an attack on Israel now could create complications with both the incoming president and the outgoing administration, possibly motivating Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to use the remaining time of President Biden’s term to strike Iran’s nuclear facilities.

On the question of overall policy—whether to adopt a strategy of appeasement and accommodation or to escalate the conflict—the Iranian leadership must choose between a more pragmatic approach, championed by President Pezeshkian, and a more hawkish, defiant stance led by the hardliners and the Revolutionary Guards. From the Iranian president’s perspective, it is preferable for Iran at this stage to focus on addressing its internal challenges, particularly the economic crisis, by seeking a settlement with the West on the nuclear issue, which could lead to a relaxation of sanctions. In this spirit, when the results of the US election were announced, the Iranian media affiliated with the pragmatic-reformist camp called for a return to the negotiating table to reach an agreement with the new American administration, thus leveraging Trump’s declared willingness to reduce tensions and resolve international conflicts. In contrast, the media associated with the hardliners argued that Trump’s re-election proves once again that hopes for a settlement with the United States are futile. They contend that Iran’s president and his allies must not revert to the approach of former President Rouhani, who made significant concessions under the failed nuclear deal with the West.

Iran’s Supreme Leader Khamenei recently appeared to suggest his openness to renewed negotiations with the United States. In an August 2024 meeting with members of Pezeshkian’s new government, Khamenei stated that while Iran should not pin its hopes on or rely on its adversaries, there is nothing preventing interaction with them under certain conditions. His statements, along with his acceptance of Pezeshkian’s presidential appointment and the appointment of former members of Iran’s nuclear negotiation team—particularly former Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif—to senior positions, may indicate a willingness to engage in dialogue with the United States, especially as the expiration date for the snapback mechanism in the nuclear deal approaches in October 2025. However, it remains doubtful whether Khamenei will be prepared to soften his position or agree to meaningful concessions on the nuclear program that would facilitate a settlement with the new administration in Washington, particularly one that the US would consider a new and improved agreement.

To sum up, the election of President Trump, Iran’s increasing willingness to take more risks than before, the limited influence of more moderate circles in Iran (even after Pezeshkian’s election as president), and the growing influence of the Revolutionary Guards, who often adopt a more hawkish and defiant stance toward the West—these factors heighten the risk of a more severe confrontation between Iran and the United States, with the reasonable possibility that during President Trump’s term, Iran will face the challenge of a change in its supreme leader.