Publications

Special Publication, September 1, 2025

Since the outbreak of the war in the Gaza Strip, humanitarian aid has played a dual role: it is both a life-saving necessity for the Palestinian population suffering from severe and ongoing hardship and a flashpoint for disputes and struggles between competing interests. This article presents the developments in the humanitarian arena during the months of war, as well as the discussions and controversies that have emerged in this complex and charged context, divided into three distinct periods. Each period reflects a shift in the aid mechanism and/or its scope, illustrating how humanitarian aid to Gaza has become another battleground in the ongoing war, a strategic tool in the struggle for control, shaping the narrative, and gaining international legitimacy.

Humanitarian aid is one of the most prominent and widely discussed issues in the context of the war in Gaza, primarily due to its critical role in ensuring the survival of the Palestinian population in the Strip. Simultaneously, it has also become one of the most sensitive and contentious issues. Like other aspects related to the war, it is accompanied by a flood of information, including official and media reports, which reveal significant discrepancies in data, alongside partial, biased, and even misleading information. As a result, the humanitarian issue has become a source of disputes and disagreements, making it challenging to construct a clear and reliable picture of the aid to Gaza.

Moreover, humanitarian aid has evolved into a battleground of its own within the broader conflict in Gaza. The dependency of Gaza’s population on humanitarian aid for basic survival, combined with the operational and political challenges surrounding access and distribution, as well as the competing agendas of various actors, has transformed aid into a contest for influence, legitimacy, and control. Questions regarding the volume and distribution of aid are no longer aimed solely at providing humanitarian response or logistical solutions. Rather, they have become significant strategic, cognitive, political, and legal tools for narrative dominance and international legitimacy, further complicating efforts to grasp the true humanitarian situation on the ground.

This article presents the developments that have occurred in the humanitarian arena during the war, based on reports and data published by official bodies from both the United Nations and Israel. Within this framework, it will examine the evolving dynamics of the humanitarian arena, including changes in the volume of aid and in coordination and distribution mechanisms, as well as the impact of competing interests and power struggles among the three key actors: Israel, Hamas, and the UN, within the humanitarian context.

Aid in Three Periods

The humanitarian aid landscape will be analyzed across three periods that mark key phases of the war:

- First Period: From the outbreak of the war until the second ceasefire (October 2023–January 2025)

- Second Period: From the second ceasefire, followed by the suspension of aid (January–May 2025)

- Third Period: Operation Gideon’s Chariots and the launch of the new humanitarian mechanism (GHF) (May 19, 2025 onward)

Each of these phases marks a turning point in the aid delivery system or its scope. This division aims to provide an understanding of the humanitarian landscape that has evolved alongside the war, including the humanitarian challenges that have emerged, the policies adopted to address them, the competing interests, and the struggles that have characterized each phase.

First Period: From the Outbreak of the War Until the Second Ceasefire (October 2023–January 2025)

Throughout most of the months of war, from October 7, 2023, until the second ceasefire on January 19, 2025, the humanitarian aid system for the Gaza Strip operated almost exclusively in a “traditional” format accepted within the international arena. This format relied on the existing infrastructure and systems of the United Nations and both international and local aid organizations.

The aid itself was donated by states, UN agencies, international NGOs, nonprofit associations, and private donors. The logistical management—including transport, storage, and distribution, was carried out by the UN and its partners in Gaza. Alongside food and water, the aid included medicines, medical equipment, and support for medical facilities, as well as supplies for shelter, fuel, and gas.

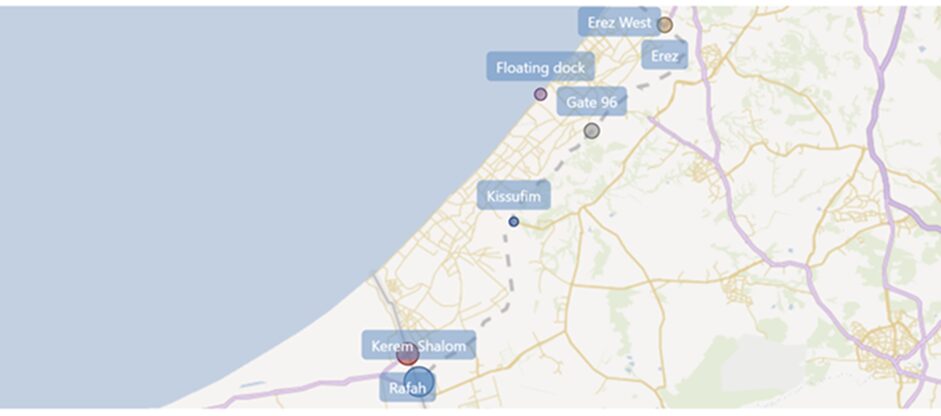

Most of the aid entered the Strip through Kerem Shalom and Rafah crossings in the south; Crossing 147 (Kissufim) in the center; Gate 96; and the Erez East and West crossings in the north. Smaller quantities of aid were delivered via airdrops and through a maritime pier, which operated only briefly (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Land Crossings and the Maritime Pier

Source: OCHA.

Inside Gaza, aid was collected from the border crossings and initially moved to logistical facilities across the Strip for storage and sorting. From there, the aid was delivered to distribution points managed by aid agencies and organizations and distributed to civilians according to humanitarian needs and international standards, with priority given to vulnerable populations. The aid system included monitoring mechanisms such as cargo tracking, field inspections, and community feedback.

Trends, Patterns, and Key Outcomes

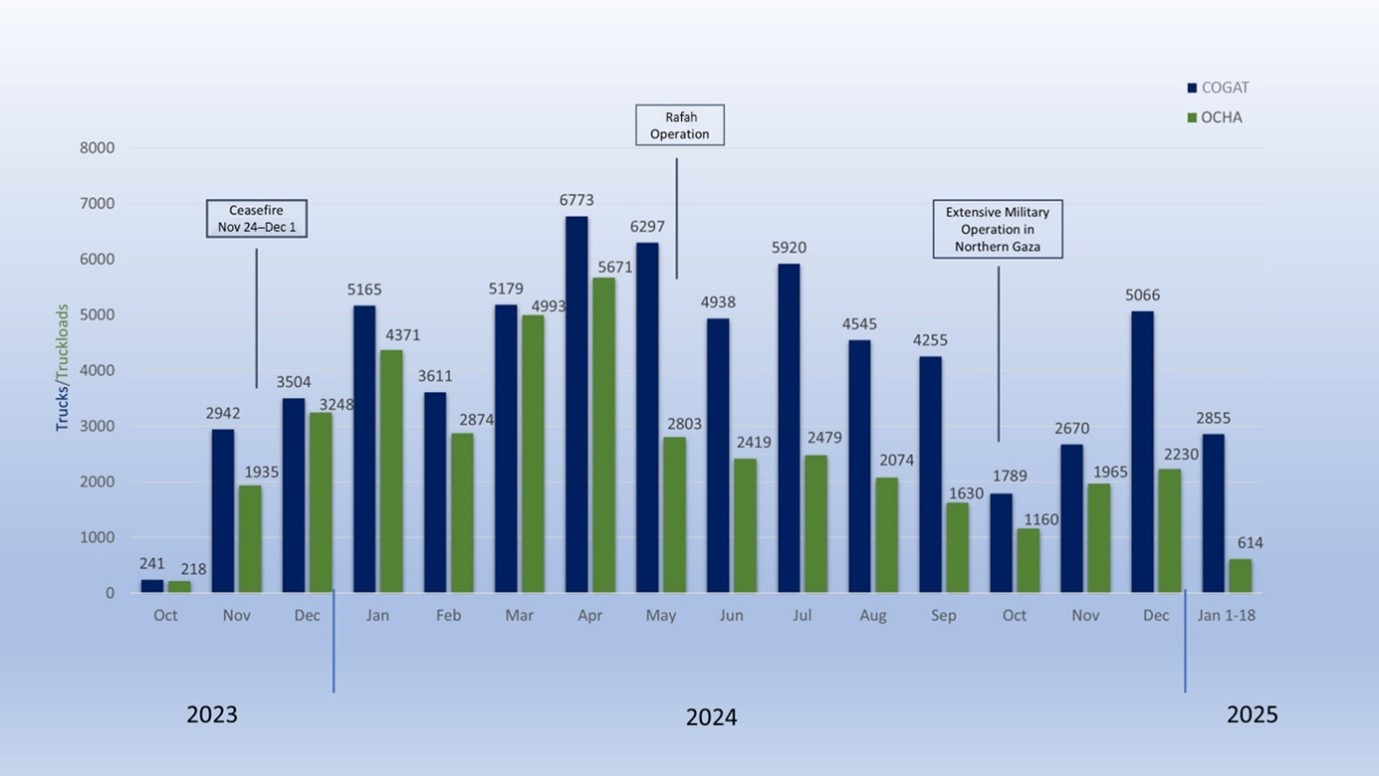

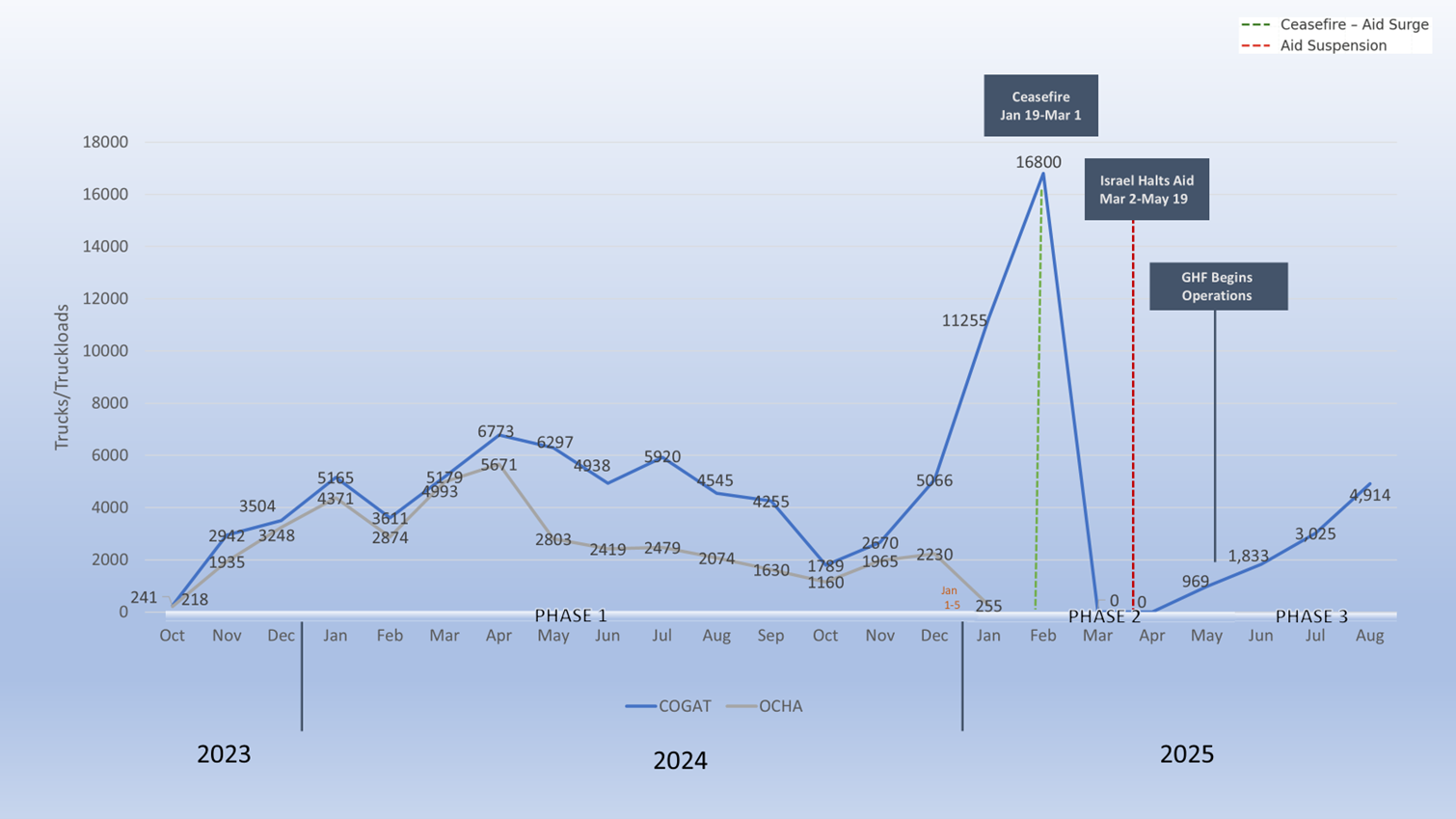

In the war’s initial phase, the volume of humanitarian aid entering the Gaza Strip increased at a relatively steady pace, according to the two primary official sources: Israel’s Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). As the period advanced, COGAT’s data showed stabilization with minor fluctuations, whereas OCHA’s figures indicated a decline. Throughout, the two datasets displayed persistent and significant discrepancies, with OCHA consistently reporting markedly lower aid volumes than those recorded by COGAT (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Monthly Humanitarian Aid to Gaza During the First Period

The chart illustrates the consistent gaps between UN (OCHA) and Israeli (COGAT) data, showing how the volume of aid directly reflected the intensity of fighting, which rose and fell with operational developments. | Source: Adapted from data provided by COGAT and OCHA Reported Impact Snapshot.

In the first half of this period, volumes of aid gradually increased, peaking in April 2024, when, according to COGAT, over 6,700 aid trucks entered Gaza, compared to around 5,600 trucks, according to OCHA. In the second half of the period, both sources indicated that the aid figures had become moderately stable. However, while COGAT’s data remained relatively high and steady from May 2024, except for a sharp drop in October 2024 due to intensified fighting in northern Gaza, OCHA’s data declined significantly after April 2024 and reported consistently lower numbers until the end of the period, resulting in monthly discrepancies of thousands of trucks.

These persistent gaps stem from fundamental differences in data collection methods: COGAT reports include all aid shipments from all sources and all crossings. In contrast, OCHA’s reports are based on partial data collected by sources inside Gaza, reflecting only aid that was received and registered by UN agencies when their representatives were present at the border crossings - thereby do not capture the full scope of incoming aid from all entry points.

Despite these inherent and substantial discrepancies, OCHA’s figures continue to serve as the primary reference for international estimates and public statements. At the same time, Israel’s more comprehensive data have been largely excluded from the international discourse.

These discrepancies in the data, along with claims about denied humanitarian coordination requests, formed the basis for accusations that Israel was preventing the entry and distribution of humanitarian aid to and within Gaza. These accusations surfaced at the outset of the war and were amplified by initial remarks from Israeli officials immediately after October 7, referring to the intention of a comprehensive siege to block supplies from Hamas. In practice, however, following a short closure of the crossings in response to the Hamas attack, the flow of humanitarian aid resumed on October 21, 2023, drawing also on stockpiles already inside Gaza. Throughout this period, Israel emphasized its commitment to facilitating the passage of humanitarian aid and presented concrete actions (in both "weekly" and other general reports) as well as detailed data showing a significant increase in the volume and consistency of aid entering the Strip.

Nevertheless, these claims quickly escalated into grave legal allegations of deliberate starvation. They were cited in the genocide proceedings initiated at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) as early as December 2023, and later advanced before the International Criminal Court (ICC), leading to the issuance of arrest warrants against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant in November 2024.

Conflict Dynamics, Not a Starvation Policy

Contrary to accusations that Israel pursued a deliberate starvation policy, aid volumes and distribution closely tracked shifts on the battlefield, rose and fell in response to key military and political developments that shaped both access and scale. In other words, aid flows reflected the conflict’s dynamics rather than an intentional policy of starvation. Periods of intensified hostilities temporarily reduced humanitarian access, while moments of relative calm enabled a marked increase in aid delivery to the population. Accordingly, the first ceasefire, which took effect in late November 2023, led to a significant rise in aid entering Gaza, peaking in April 2024. In contrast, the renewed escalation of fighting in October 2024, particularly in northern Gaza, led to a dramatic decline in both the volume of aid and its access.

These trends highlight how shifts in the intensity of hostilities, alternating between escalation and relative calm, directly affected the volume and consistency of humanitarian assistance. They emphasize the close relationship between operational conditions, security constraints, and the ability to ensure consistent delivery of aid to Gaza’s population.

Moreover, the flow of humanitarian aid was also shaped by Gaza’s unique operational conditions and by Hamas’s direct role in shaping them. The Gaza Strip, a small, densely populated area of approximately 365 square kilometers, among the most crowded in the world with a population of more than two million people, was transformed under Hamas’s rule into an exceptionally complex urban battlefield. Hamas has deliberately exploited and disrupted the civilian sphere by systematically entrenching itself within densely populated areas; embedding military infrastructure in private homes, schools, mosques, hospitals, and even aid facilities. This was further reinforced by an extensive underground tunnel network, used for logistics and combat in close proximity to civilians.

All this transformed Gaza into a dense and highly complex battlefield, making humanitarian access particularly fragile and contingent upon the terrain and the intensity of the fighting. Any escalation, even a localized one, could immediately disrupt supply lines and force closures of routes, paths, and distribution centers.

Despite these challenges, throughout this period, Israel facilitated the continued flow of aid, gradually increasing its volume, opening additional crossings, and allowing the establishment of alternative delivery mechanisms, including airdrops and via the maritime pier, which operated only briefly. All this occurred under severe operational constraints in territory effectively controlled by Hamas, and amid ongoing efforts to prevent the aid from falling into the hands of the terrorist organization. It is important to underscore that in the initial stage of the war, Israel did not control the internal distribution mechanisms of aid within Gaza; this responsibility rested with the UN and its partner organizations.

During this period, however, increasing evidence indicated that Hamas systematically diverted portions of the humanitarian aid, particularly food supplies, to maintain its rule, sell in local markets, and support its military operations. This practice undermined efforts to ensure that aid reached the civilian population and exposed the weaknesses of existing UN mechanisms, which are supposed to oversee aid distribution and guarantee neutrality, fairness, effectiveness, and protection from hostile exploitation. In many cases, reliance on local infrastructure under Hamas’s influence, including the use of Hamas's police to escort aid convoys to shield them from local gangs, contributed, even if unintentionally, to the organization’s access to aid and reinforced its control over the population.

Despite these circumstances, the starvation narrative became deeply entrenched in the international discourse, significantly shaping public and policy perceptions of Israel and resulting in substantial legal and diplomatic consequences for the country.

Reinforcing the Starvation Narrative

The starvation narrative received significant reinforcement through reports issued by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), a global partnership that assesses food crises and ranks acute food insecurity on a five-phase scale, with the last three escalating from “Crisis” (Phase 3) to “Emergency” (Phase 4) to “Catastrophe” and “Famine” (Phase 5).

Crucially, a Phase 5 “Famine” designation requires strict benchmarks: at least 20% of households face extreme food shortages, 30% of children suffer from acute malnutrition, and a daily mortality rate of two adults or four children per 10,000. While these criteria do not deny the existence of severe distress, they set a clear threshold for distinguishing between these conditions and famine. These thresholds stand in stark contrast to the broader famine narrative that often took hold.

Relying heavily on incomplete OCHA data, the IPC warned in December 2023 that famine could occur by May without a ceasefire, and by March 2024, described famine as “imminent” in northern Gaza, classified it as Phase 5 (“Famine”) with reasonable evidence, projecting it would spread across the Strip by July. These projections significantly shaped international perceptions and heightened pressure on Israel.

In practice, not only did these forecasts fail to materialize, but in July 2024, the IPC was forced to revise its June report, reducing by more than 50% the number of people facing catastrophic levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 5). This revision followed an internal audit by the organization’s Famine Review Committee (FRC), which found no evidence of an ongoing famine, identified significant discrepancies in the reported data, and observed that the level of humanitarian aid entering Gaza exceeded the nutritional threshold required to prevent famine conditions.

Subsequent IPC and FRC reports in September and November 2024 continued to warn of potential deterioration and “high risk of famine,” but they clearly stated that the “famine” thresholds were never met and that considerable aid had reached Gaza over several months.

In reality, none of the dire forecasts made by the IPC materialized during 2024 or in the first half of 2025.

The ongoing gap between these alarming projections and the actual conditions highlights that, although severe humanitarian distress indeed prevailed in the Gaza Strip during this period, claims of “famine” or “intentional starvation” were unfounded and based on partial data and flawed assessments. Nevertheless, these projections received wide media coverage and significantly shaped global public opinion, intensifying international pressure on Israel.

Figure 3. IPC Forecasts vs. Actual Outcomes

The chart highlights a persistent gap between IPC projections of Phase 5 and real-time conditions. Except for December 2023, subsequent forecasts issued throughout the period consistently overestimated the number of people expected to reach Phase 5. The most prominent discrepancy appeared in June 2024, when IPC projections anticipated that over one million people were expected to reach Phase 5, while the actual number was approximately 343,000. | Source: Adapted from data provided by IPC.

Second Period: The Second Ceasefire and the Suspension of Aid (January 19–May 19, 2025)

Two significant events resulting from changes in the operational conditions significantly disrupted the continuous pattern that characterized the first phase of the war: a massive influx of aid during the ceasefire, followed thereafter by an abrupt suspension of aid delivery. Due to their impact and sharp deviation from the previous trend, these events are examined separately as part of the second phase of the war.

2.1 The Second Ceasefire (January 19–March 2, 2025)

On January 19, 2025, the second ceasefire between Israel and Hamas went into effect, leading to a sharp and rapid increase in the volume of humanitarian aid entering the Gaza Strip. Under the terms of the ceasefire agreement, the entry of 600 trucks per day and approximately 4,200 trucks per week was permitted through the Erez, Zikim, and Kerem Shalom crossings. Aid deliveries were coordinated with UN mechanisms and humanitarian partners, relying on the existing distribution infrastructure within the Strip.

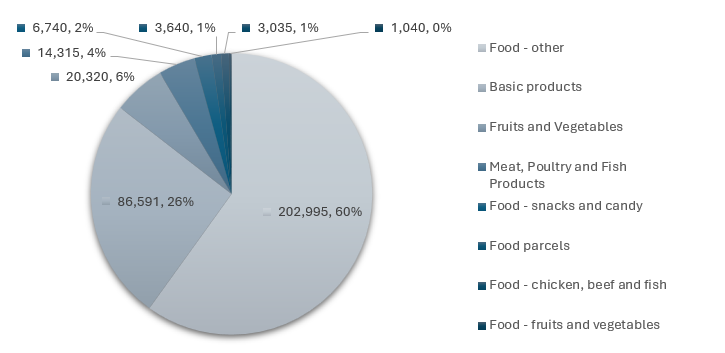

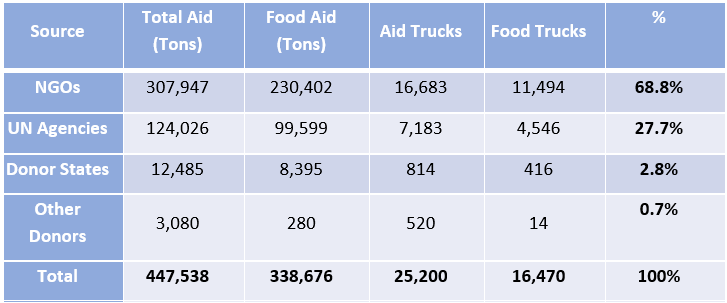

During this period, approximately 25,200 trucks entered Gaza, delivering a total of 447,538 tons of humanitarian aid, including food, water, medical supplies, shelter items, fuel, and gas (Figures 4 and 5).[1] Of these, around 16,470 trucks transported approximately 338,676 tons of food (Figure 6).

The cessation of fighting also significantly eased restrictions on the internal movement of aid within the Strip. For the first time in months, aid trucks and humanitarian missions were able to access areas that had previously been inaccessible. However, movement between the southern and northern parts of the Strip remained partially restricted.

Data Sources

The data for this period relies primarily on official figures from Israel’s COGAT, as UN's OCHA ceased publishing real-time truck entry data through its online dashboard at the start of the ceasefire. From that point on, OCHA released only its written reports containing sporadic and limited information on food distributions, flour rations, and humanitarian supplies. Notably, OCHA did not issue any public statements disputing COGAT’s figures regarding the volume of aid delivered during this period, aid that Israel had committed to facilitating under the terms of the ceasefire agreement.

Humanitarian Impact

The surge in humanitarian aid during the ceasefire period led to a significant improvement in humanitarian conditions within the Gaza Strip. However, concerns quickly surfaced over the diversion of aid by Hamas, underscoring the need for strict monitoring and verification mechanisms.

Figure 4. Ceasefire Aid Volumes (*Trucks)

The total number of trucks, including fuel and gas, as well as airdrops at the crossings. | Source: COGAT.

Figure 5. Ceasefire Aid Breakdown by Type (*Tons)

Most of the aid consisted of food products, with smaller portions of shelter equipment, medical supplies, and water. | Source: COGAT.

Figure 6. Ceasefire Food Breakdown by Type (*Tons)

Most of the food distributed during the ceasefire (86%) consisted of general and basic staple goods, focusing on caloric coverage over dietary diversity. “Basic products” included items such as flour, rice, sugar, and cooking oil. “Food packages” consisted of ready-to-eat, pre-packaged meals. “Food other” referred to trucks with mixed food items, airdrops, canned goods, high-energy biscuits, and more. | Source: COGAT.

2.2 Suspension of Humanitarian Aid After the Collapse of the Second Ceasefire (March 2–May 19, 2025)

Following the collapse of the second ceasefire on March 2, 2025, Israel decided to suspend the entry of humanitarian aid into the Gaza Strip. This move aimed to sever Hamas from critical supply lines and apply political and military pressure on the organization in an effort to increase its flexibility in negotiations over the release of the hostages. The decision was based on accumulating evidence of Hamas’s systemic exploitation of humanitarian aid, including the seizure of aid trucks, hoarding of supplies, diversion of aid for military needs, and use of aid in internal trade to finance terrorist activity.

Israel made this decision, understanding that a substantial stockpile of aid remained in Gaza following the 42-day ceasefire, during which, as previously mentioned, approximately 25,200 aid trucks had entered the Strip. This volume exceeded the total aid delivered to Gaza during the six months prior to the ceasefire and constituted nearly one-third of all aid that had entered the Strip since the war began in October 2023. In the food sector alone, approximately 338,676 tons were delivered, an amount deemed sufficient by international standards to meet the basic needs of the civilian population for at least five months.

Nevertheless, the suspension of aid did not achieve its strategic objectives. Hamas did not show increased flexibility in the subsequent negotiations. At the same time, reports from inside Gaza began to suggest that food and aid stockpiles were dwindling. By late March, less than a month after the suspension, UN officials warned that their supplies were expected to last only two more weeks, and that a significant deterioration in the humanitarian situation was anticipated if aid did not resume immediately.

Problems With the UN Warnings

The gap between warnings and the volume of aid delivered. The UN alerts stood in stark contrast to the substantial volume of aid that entered Gaza during the ceasefire period preceding the suspension, as well as to the reasonable assumption that significant stockpiles should have remained available for continued use. The fact that the UN issued warnings about severe shortages so quickly and continued to do so throughout the period raised serious questions regarding the management and distribution of the aid that had been delivered. If such large volumes of aid entered Gaza, where did it go?

Lack of transparency. The UN’s warnings focused on the rapid depletion of aid stockpiles without explaining the disappearance of previously delivered supplies. The absence of transparent data regarding distribution methods, storage, and oversight on the ground made it difficult to assess the causes: whether it was due to inefficient use, diversion of aid to unauthorized actors (such as Hamas), or some other logistical failure.

Partial representation of aid. The alerts referred only to UN-managed aid, which reportedly comprises only about 30% of the total aid entering the Strip, without addressing the remaining 70% delivered by other international organizations, countries, and private donors. This lack of distinction raised concerns about overestimating the severity of the crisis and may have been an attempt to deflect attention from failures in the management and transparency of the aid system (Table 1).

Table 1. Ceasefire Aid Breakdown by Source

Source: Data from COGAT.

Narrative pressure. The one-sided wording, urgent timing, and severe tone of the UN’s alerts created an atmosphere of immediate humanitarian emergency, even though the volume of aid entering Gaza before the suspension had been exceptionally high and stockpiles should have been expected to last. In this context, such alerts could be interpreted as attempts to exert international pressure on Israel to resume aid delivery and could be seen as politically motivated rather than a balanced, data-driven, strictly logistical, or professional assessment, particularly in the absence of explanations or accountability for possible obstacles.

In the absence of comprehensive and transparent reporting and coordination among all aid actors, it has become increasingly difficult to objectively assess the humanitarian situation on the ground. This contributed to widening the gap between factual realities and international political and public discourse, which attributed exclusive responsibility to Israel for the humanitarian situation in Gaza.

This gap was particularly evident in light of the April 2025 IPC report, which indicated measurable improvement: The percentage of the population classified in Phase 5 (Catastrophe) decreased by four percentage (from 16% to 12%) between April 1 and May 10, reflecting a shift of approximately 101,000 people to lower phases on the IPC food insecurity scale.

These findings suggest that, despite the ongoing humanitarian distress, conditions on the ground at that time did not substantiate claims of severe shortages or the onset of famine. In fact, the total available stockpiles, including those not managed by the UN, provided nutritional support for a longer period than the UN claimed, as was also reflected in the IPC’s April 2025 report.

Nevertheless, the claims of rapid depletion of food and aid stockpiles raised serious concerns about Hamas’s control over internal distribution channels and its capacity to divert aid away from the civilian population. This pointed to a deeper structural problem: The traditional aid distribution mechanism, even when driven by humanitarian intent, is inadequate and cannot guarantee that aid reaches the civilians in full. In some cases, it may actually serve Hamas’s interests and help reinforce its authority.

Ultimately, against the backdrop of reports that food supplies in Gaza were rapidly dwindling, mounting domestic and international pressure, and the resumption of hostilities, Israel announced in mid-April its intention to resume humanitarian aid deliveries to Gaza via a new mechanism designed specifically to ensure direct delivery to the civilian population and to prevent Hamas from exploiting, diverting, or confiscating the aid for its own purposes.

Third Period: Operation Gideon’s Chariots and the GHF Aid Mechanism (May 19, 2025, Until Present)

After more than two months of suspended humanitarian aid and coinciding with the launch of Operation Gideon’s Chariots, Israel resumed the flow of aid into the Gaza Strip in late May 2025. Initially, on May 19, aid resumed under the traditional mechanism led by the UN and international aid organizations. Shortly thereafter, on May 27, the new independent mechanism of the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF) was launched.

The GHF Mechanism: An Operational Alternative to the Traditional Aid Model

The GHF aid mechanism was established through U.S.-Israeli cooperation to create an alternative and independent channel of assistance. Its purpose was to bypass Hamas and ensure that humanitarian relief reached Gaza’s population through a closely monitored and controlled delivery system, free from Hamas’s interference.

Under the GHF model, aid is distributed through pre-packaged food kits, which are delivered directly to civilians via four designated distribution centers. The mechanism was initially designed to scale up and reach up to two million residents. Of the four centers, three are located in southern Gaza and one in central Gaza, all situated in evacuated areas designated as combat zones under IDF control. (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Distribution Centers of the GHF

Source: IDF Spokesperson

Private American companies manage the internal operations and security of the distribution centers, while the IDF provides perimeter security and controls access routes; however, it does not maintain any presence inside the centers or participate in the actual aid distribution.

The GHF model represents a fundamental shift in approach compared to the traditional UN-led system. While the traditional model relies on a centralized, mediated system based on “wholesale” delivery from central warehouses and local actors (some of whom are affiliated with Hamas), the GHF approach is the opposite. It is decentralized, controlled, and employs “retail-style” direct distribution at secured sites specifically to bypass Hamas’s control mechanisms.

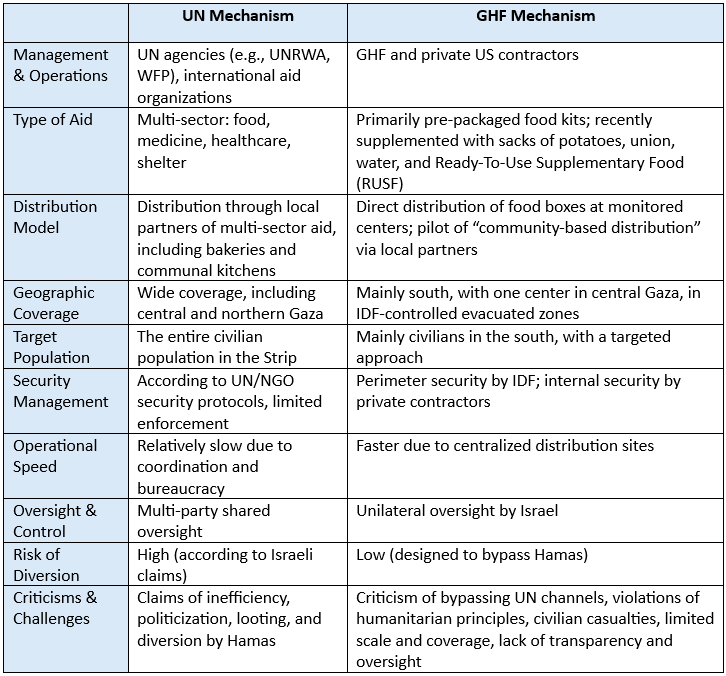

Since aid was resumed in late May, the two mechanisms have been operating in parallel in the Gaza Strip. The GHF mechanism provides direct aid to civilians, mainly in southern Gaza, while the traditional UN mechanism delivers "complementary" aid primarily by truck to northern Gaza.[2] These two mechanisms function independently and are not coordinated with each other. Key differences between them include not only their locations, but also oversight, control, types of aid, distribution models, and their ability to prevent exploitation by Hamas. (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison Between the UN Mechanism and the GHF Mechanism

Initial Impact of the GHF Mechanism

The launch of the GHF mechanism led, within weeks, to a series of developments that drew attention in the operational, humanitarian, and media domains. Among these were a widespread civilian response and increased movement of residents toward distribution centers, a phenomenon that, in effect, signaled a breakdown of the fear barrier toward Hamas. At the same time, the GHF mechanism significantly reduced Hamas’s ability to divert aid.

Supporters of the mechanism, both Israeli and international, interpreted these trends as an indication that the GHF model could represent a strategic turning point in Gaza’s humanitarian aid system. In part, the mechanism has been perceived as reinforcing the idea of a direct civilian alternative to Hamas’s governance, undermining the organization’s perceived control over the Strip, and challenging its ability to exert influence through control of humanitarian aid, especially given its diminishing capacity to intercept or appropriate such resources.

According to GHF reports, from its inception through August 26, 2025, approximately 139,328,514 meals were distributed through roughly 2,325,592boxes.

Key Shortcomings and Operational Constraints

Since its launch, the GHF mechanism has faced a range of structural and operational challenges:

- Security Failures: The placement of distribution centers in IDF-controlled, evacuated combat zones has led to repeated friction between hungry civilians and IDF soldiers securing access routes. Feelings of threat among field troops, combined with crowding, chaos, and civilian pressure, have led to shooting incidents resulting in deaths and injuries.

- Insufficient Quantity and Variety of Aid: The aid kits are limited in volume, quickly depleted, and primarily focus on basic food. They do not address broader humanitarian needs such as medicine, hygiene products, healthcare services, and sanitation. This narrow scope reduces the aid’s effectiveness, limiting it to partial and short-term support, which operates on a first-come, first-served basis, resulting in highly inequitable access.

- Limited Geographic Coverage: The four distribution centers are insufficient to meet the humanitarian needs across Gaza.

- Accessibility Barriers: Women, children, and the elderly struggle to reach the distribution sites, often walking long distances and carrying heavy loads.

- Operational Gaps: The absence of an organized system for registration, monitoring, and auditing undermines fair, equitable, and effective distribution. As a result, some civilians receive multiple boxes, while others receive none.

- Crowd Management Challenges: The lack of crowd-control mechanisms, combined with high demand, leads to chaos, overcrowding, riots, violence, and occasional breakdowns of orde These conditions compromise the security of the humanitarian operations and impair the mechanism’s ability to function continuously and safely.

- Logistical Constraints: Delays in the supply chain, limited infrastructure, and transportation challenges due to capacity constraints hinder operations.

- Dependence on Military Coordination: Requires continuous IDF support for secure access and delivery, which reduces operational independence and flexibility.

Core Challenges

In addition to operational hurdles, the GHF mechanism faces significant strategic, operational, and perception-based obstacles that undermine its effectiveness and threaten its continued operation.

A. Humanitarian Criticism

The mechanism has drawn sharp criticism from international actors for imposing strict limitations on the scope and distribution of aid, employing screening technologies (including facial recognition), relying on private security firms, and operating in military-controlled zones. Critics argue that these practices violate core humanitarian principles, particularly the protection of civilians, and raise concerns about the neutrality and independence of the mechanism. OCHA reports that between May 27 and August 18, at least 1,889 Palestinians were killed while seeking food. This includes 1,025 near GHF's distribution centers, referred to by OCHA as "militarized distribution, and 864 along supply truck routes. According to OCHA most of them, "appear to have been killed by the Israeli military," with "no information to suggest that these people were directly participating in hostilities or posed any threat to Israeli forces or other people."

B. Deliberate Disruption by Hamas

Hamas views the GHF mechanism as a direct strategic threat to its control in Gaza and has systematically worked to sabotage it. These efforts have included the sabotage of infrastructure; threats and intimidation of civilians; arrests on suspicion of “collaboration”; and deliberate gunfire at aid distribution points, resulting in the deaths of civilians and aid workers. This is a broad and systematic effort by Hamas aimed at thwarting the existence of an independent aid channel that operates outside its control, underscoring the centrality of humanitarian aid as a tool of governance and a means of deepening civilian dependency on the organization.

C. International Delegitimization

Simultaneously, several aid organizations, led by the UN, have chosen to boycott the mechanism and refuse to cooperate with it, claiming that it bypasses the UN’s accepted aid structure and violates fundamental principles of neutrality, independence, and non-affiliation. In addition to refusing to cooperate, these entities have launched a public campaign aimed at dismantling the mechanism. As part of this campaign, they have accused Israel of using food as a “deadly weapon” for military purposes and attributed direct responsibility to the IDF for violence and the deaths of hundreds of civilians at the aid distribution sites. These accusations have been endorsed by over 100 NGOs, which published a joint call to end what they have termed “the deadly Israeli aid scheme.”

These messages received wide international media coverage. In contrast, evidence from the ground, including from Palestinian sources (see here and here), of Hamas’s systematic disruption of aid efforts, including threats, denying access, incitement, violence, and shooting at civilians near distribution centers, was almost entirely ignored. Hamas’s actions are an integral part of the challenge in delivering aid and have directly contributed to the disruptions and risks around distribution centers. Yet, they are almost entirely absent from official international discourse.

The IDF confirmed that a “distancing protocol” was implemented, including warning shots near distribution centers, aimed at deterring civilians from entering areas designated as dangerous. This protocol resulted in civilian deaths and injuries. However, the IDF firmly rejected any claims of intentional harm to civilians and emphasized its commitment to investigating exceptional incidents and taking corrective measures. As part of this effort, several changes were implemented on the ground, including rerouting access paths, improving signage, installing new barriers, and relocating a central distribution center, all aimed at reducing the risk of harm to civilians. Operational field instructions were also revised accordingly.

Strengthening the Mechanism and Expanding Its Capabilities

While the GHF mechanism introduced an innovative humanitarian paradigm, its initial results were relatively modest. It required time to stabilize and operate effectively, despite the sincere efforts of its operators. Recent initiatives, including targeted allocations for women and children, expanded food items, community-based distribution, and a pilot pre-registration system, represent significant progress, with incidents of crowding and disorder at distribution centers nearly eliminated.

Still, the medium and long-term success of the GHF relies on its ability to improve continuously and establish itself as a safe, effective, and widely accepted model. To achieve this, it must increase both the volume and diversity of aid, ensure broader geographic coverage, maintain consistent protection standards at distribution sites, and establish a robust registration and tracking system to enable precise oversight of aid flows and ensure equitable, effective distribution. These measures are essential to meeting the humanitarian needs in Gaza and ensuring the continued operation of the mechanism.

However, the success of the GHF depends on international mobilization. If the UN and major humanitarian organizations were to respond to the GHF's calls and engage with the mechanism, even partially, the humanitarian response in Gaza would be significantly expanded in terms of funding, operational capacity, monitoring, and deployment, while integrating international standards.

The Humanitarian Crisis in Gaza

After nearly two years of fighting, Gaza is facing a severe humanitarian crisis, with its civilian population entirely dependent on humanitarian aid for basic survival. The harrowing images of hunger and deprivation among civilians offer a stark reflection of the crisis’s accelerating severity, which escalated sharply by late July. The roots of this crisis lie less in a shortage of aid and more in issues of political control, growing chaos, distribution failures, and the conduct of various actors on the ground.

The disparity between the volume of aid provided and the reality on the ground further highlights the scale of the failure. According to COGAT data, from January to the end of July 2025, prior to the recent increase in aid, a total of 33,882 aid trucks entered Gaza. This included 23,871 trucks carrying nearly half a million tons of food, enough to meet the nutritional needs of the entire population. This volume nearly exceeds the monthly requirement of 62,000 tons needed for the people of Gaza and approaches pre-war annual levels.

Yet, despite all this, the humanitarian crisis in Gaza is real and worsening. The core challenge is the population’s ability to access aid, rather than the amount of aid. That access is undermined by systemic, interrelated failures: issues within distribution centers, including deliberate disruptions by Hamas; hoarding of aid out of fear of future shortages; looting and diversion of aid trucks by Hamas, local clans, criminal gangs, armed militias, and profiteering merchants into the black market, driving food prices to unprecedented highs by mid-July.

All of this was unfolding against the backdrop of mass evacuations, the shrinking of designated humanitarian zones, the collapse of civil infrastructure, and the breakdown of civil order across the Gaza Strip. These factors have severely undermined the ability to ensure consistent, equitable, and secure aid delivery - free from hostile interference.

As a result, while the humanitarian system continued to generate aid flows, it failed to distribute them, leaving large segments of Gaza’s population in acute hunger. These combined factors have created localized “hunger pockets,” primarily in the northern part of the Strip and in areas affected by ongoing conflict. Ground reports highlighted a growing disparity between official records of food aid entering Gaza and its actual availability to civilians. Ultimately, only a fraction of the aid ever reaches those in genuine need. Vulnerable groups, displaced families, children, the elderly, and those lacking clan or political protection are often the last to receive aid or are excluded altogether, deepening humanitarian suffering. This reality was echoed in Gazan social media, captured in the repeated refrain: “The food may have entered Gaza - but it hasn’t reached our mouths.”

After twenty-two months of war, Gaza has been devastated by widespread destruction of infrastructure and repeated evacuations. An estimated 75% of the territory is now classified as an active combat zone, with UN sources placing the figure as high as 86%. A significant share of the population is crowded into makeshift shelters, living without reliable access to food, clean water, or medical care, as healthcare, sanitation, livelihoods, and social services have largely collapsed. In this reality, any depletion of the little that remains leads to a rapid deterioration of the humanitarian situation, with immediate and profound consequences for the civilian population.

In the absence of governance and as chaos increases, Gaza is becoming a lawless land.

Aid as a Battlefield

Amid this harsh reality, Hamas has sought to leverage the humanitarian crisis as part of a coordinated campaign during the ceasefire negotiations in July. Their goal is to generate political and diplomatic pressure on Israel to both expand the flow of aid trucks and dismantle the GHF mechanism. The group has insisted that the UN and the Palestinian Red Crescent be granted exclusive control over aid distribution in Gaza, rejecting any arrangement that involves the independent GHF mechanism or even partial cooperation with it. Underlying these demands is the reality of governance and economic collapse: Hamas is struggling to pay its operatives, sustain basic civilian services, and maintain public loyalty. In this context, access to humanitarian aid has become a core pillar of Hamas’s ability to sustain itself, making influence over aid flows vital for its survival.

For Hamas, aid is not just a humanitarian resource, but also a strategic asset, critical to consolidating its control, shaping international narratives, and applying political pressure. The organization continues to prioritize the preservation of its own power over the welfare of its people. Hamas perpetuates the very crisis it condemns, creating the conditions of crisis while simultaneously exploiting them as a tool of influence. It portrays Gaza’s suffering solely as Israel’s doing, while obscuring its direct and central responsibility for the situation. In doing so, it seeks to fuel international outrage against Israel, gain political leverage, and shield itself from scrutiny over its governance failures. While accusing Israel of starving Gaza, Hamas has rejected proposals from Israel and the United States, sabotaged the July ceasefire talks, and chose instead to prolong the war, deepening the humanitarian crisis and the suffering of Gaza’s civilians.

The UN and its agencies have joined the campaign against Israel, effectively granting Hamas the operational space needed to maintain its control. Instead of addressing Hamas’s control mechanisms, the looting of aid, intimidation, and gunfire directed at civilians, as well as widespread distribution failures, the UN has focused its criticism on Israel. It claimed that the allegations against Hamas were not supported by evidence, despite the extensive documentation provided by Israel as well as testimonies from people in Gaza (see here, here, and here). The UN has accused Israel of deliberately starving the population while refusing to cooperate with the GHF and even preventing other aid organizations from partnering with it. Such cooperation could have significantly mitigated the humanitarian deterioration in the Strip. Meanwhile, urgently needed humanitarian aid has been sitting idle at the crossings into Gaza, waiting to be collected by the UN. Hundreds of trucks remained stranded, warehouses stayed closed, and critical equipment was left unused. The UN attributed these delays and aid stockpiles at Gaza’s crossings to access constraints stemming from destruction, ongoing combat, threats to its staff and facilities, IDF movement restrictions, and permit denials.

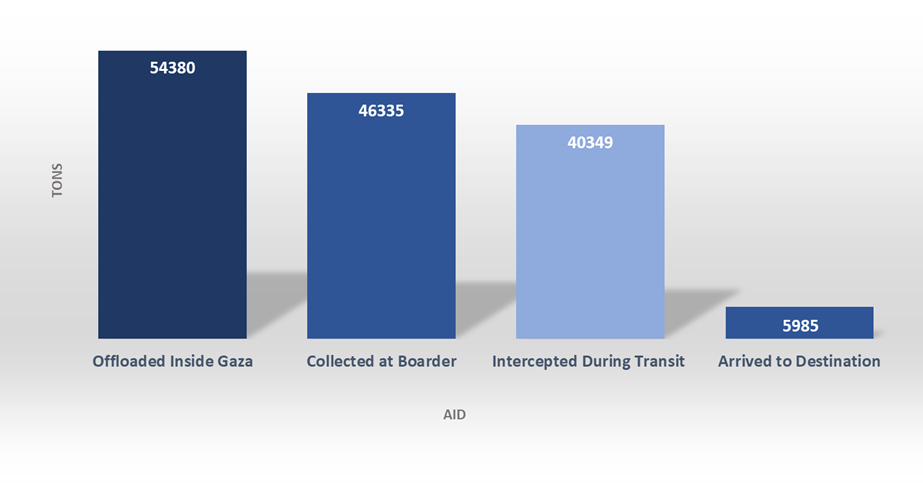

However, this framing downplays the fact that in most areas of the Strip, aid entry continued largely uninterrupted, and the main obstacles were structural and operational breakdowns. According to UN data between May 19 and August 12, 2025, nearly 90% of aid entering Gaza via the UN Mechanism was looted or diverted by either "hungry people or forcefully armed actors" before reaching its destination. (Figure 8). Crucially, when UN movement and permit requests were denied, it was not to limit aid, but due to security concerns and to prevent the diversion of resources to Hamas. This included requests for police escorts from Hamas or sensitive communication equipment.

Israel insists it imposes no limits on aid, pointing to thousands of trucks cleared since May, and that the real problem lies in UN inefficiency, refusal to use approved routes, and Gaza’s internal lawlessness following the collapse of local governance. Nonetheless, Israel has also used humanitarian aid as a strategic lever, a tool of pressure aimed at weakening Hamas’s control over key power centers, through strict management and oversight of distribution channels. As a result of this approach, the already deteriorating humanitarian situation in Gaza has worsened, leading to increased shortages and deepened civilian suffering. Consequently, Israel has played a significant role in shaping the current humanitarian crisis. (Further elaboration will follow).

The international community, for the most part, accepts the UN's narrative with little scrutiny and often turns a blind eye to Hamas’s crimes, even when they are directed at the Gazan population. Rather than examining the structural and systemic factors underlying the crisis, particularly the central role played by Hamas in both creating and perpetuating these conditions, it places responsibility solely on Israel, while largely disregarding the broader context and the fundamental failure of a local governing body acting against the interests of its own people, and without demanding accountability for what has happened to the aid they contribute to Gaza.

This dynamic has turned humanitarian aid to Gaza into yet another front in the ongoing conflict, with the civilian population trapped between competing political interests and strategic agendas of key actors. While the primary purpose of aid is to meet basic humanitarian needs, it has also been instrumentalized, serving as a tool for asserting control, influencing narratives, and securing international legitimacy. As a result, throughout the war, gaining a clear, objective, and reliable picture of the humanitarian situation in Gaza has become increasingly challenging.

Accordingly, any credible assessment of the humanitarian situation in Gaza must take into account the full range of contributing factors and actors, including their conflicting interests. Ignoring them leads to a distorted picture, unfounded blame on Israel, and ultimately strengthens Hamas, while obscuring the truth and hindering the path toward effective and meaningful humanitarian response.

This was illustrated with painful clarity in the latest IPC report, published on August 22, 2025, which confirmed that famine (IPC Phase 5) is occurring in the Gaza Governorate. The report has faced significant criticism for methodological flaws and scientific compromise, including altering measurement criteria to support a "famine" classification, as well as structural bias against Israel reflected in its tone, rhetoric, framing, and authorship. These shortcomings raise serious concerns about the validity of its findings and warrant caution in treating them as established facts (see here and here).

Nonetheless, even if the IPC's findings are accepted, Gaza’s humanitarian crisis cannot be explained by Israeli actions alone. The report attributes famine drivers solely to Israel while downplaying inconvenient truths and avoiding explicit reference to Hamas’s central role in the crisis: its exploitation of civilians, militarization of hospitals, diversion of aid, and prolongation of the war through its continued holding of hostages, as well as the UN oversight and distribution failures. Instead, the report places full responsibility for all actions and all failures on Israel.

In doing so, the IPC report distorts reality and undermines its own credibility. More critically, by misrepresenting the drivers of Gaza’s humanitarian collapse, it perpetuates existing shortcomings, misdirects resources, weakens accountability, and enables exploitation, ultimately undermining the foundations of an effective humanitarian response by treating symptoms rather than addressing the root causes of the crisis.

Figure 8. UN-Manifested Humanitarian Aid Movements from 19 May to 12 Aug 2025

The graph illustrates a significant decline in aid distribution within the UN Mechanism across four stages. Of the 54,000 tons of aid initially offloaded into Gaza, only about 6,000 tons, just over 10%, actually reached their intended destination. The majority of losses occurred within Gaza after the aid had been collected for distribution. | Source: UNOPS, UN2720 Mechanism for Gaza.

Israel’s Humanitarian Aid Policy

Israel’s aid policy toward Gaza has developed gradually but underwent a significant shift during the war. Initially, Israel relied on the existing international framework, primarily UN mechanisms, without a cohesive systemic approach, while adapting its policy to humanitarian and operational constraints, security needs, and political and diplomatic considerations. Subsequently, as the fighting intensified and evidence mounted of Hamas’s systematic exploitation of aid, including its diversion for military purposes and its use as a tool of civilian control, alongside the inability of the UN mechanisms to prevent such diversion, Israel’s approach changed significantly. At first, this shift was expressed in the suspension of aid to Gaza immediately following the ceasefire, as a controlled pressure tactic. When this measure proved ineffective, Israel established an alternative independent aid mechanism (GHF), designed to sever Hamas’s access to humanitarian aid, establish full and effective oversight, and facilitate direct access to assistance for the civilian population. (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Humanitarian Aid to the Gaza Strip in the Three Phases of the War: October 2023–July 2025

Source: Adapted from data provided by COGAT and OCHA Reported Impact Snapshot.

The GHF mechanism reflected a fundamental shift in the underlying approach, from cooperation within the international humanitarian framework, relying on existing systems, to an independent model of direct aid management and distribution. However, in practice, Israel’s policy remained ad hoc, responding to constraints and crises without a broad strategic vision.

More broadly, Israel’s aid policy in the Gaza Strip, as it evolved throughout the war, reflects an effort to provide humanitarian assistance to a civilian population governed by a hostile regime that is entrenched within civilian infrastructure and actively exploiting humanitarian aid for its own purposes. In this reality, Israel was compelled to navigate a delicate balance: ensuring continuous and secure humanitarian access for civilians while also preventing Hamas from diverting that aid to sustain its rule and prolong the war. In some cases, Israel succeeded in maintaining this balance; in others, it did not. However, it is important to emphasize that at no point did Israel adopt a deliberate policy of starvation. Even when it temporarily suspended aid to the Gaza Strip, the move was intended to preserve leverage over Hamas, with the understanding that substantial assistance was already available within the Strip.

In recent months, since the collapse of the second ceasefire, Israel has prioritized immediate operational considerations, choosing to intensify its direct use of humanitarian aid as a tool of leverage against Hamas, initially by suspending aid entirely, and subsequently by asserting control over the distribution mechanism – hoping it would deliver a decisive blow to the group and potentially bring an end to the war. Nonetheless, aid has remained a tactical add-on to the broader military campaign rather than being developed into a coherent, independent strategy. The GHF mechanism was introduced as an emergency solution, without sufficiently addressing its security, operational, and logistical aspects. Despite prior warnings and the lack of international support, Israel chose to advance the mechanism as part of Operation Gideon’s Chariots. In practice, insufficient efforts were made to ensure that aid reached those most in need, while humanitarian conditions and living standards in Gaza have continued to deteriorate amid the ongoing war, rendering the policy’s failure inevitable.

This was further compounded by a fundamental cognitive failure: Israel did not formulate a narrative to accompany its humanitarian policy, and did not prepare for the predictable cognitive assault by Hamas in the international arena. As a result, while Israel facilitated aid, it was perceived as the party blocking it. Hamas once again seized control of the international narrative, while Israel lost control of the humanitarian arena and the story being told to the world. Statements by extremist senior Israeli officials, including government ministers, regarding the “flattening of the Strip,” “halting aid,” establishing a “humanitarian city,” and initiatives promoting “voluntary emigration” and “settlement in Gaza” were not met with clear public condemnation. These remarks reinforced the perception of Israel’s malicious intent, strengthened the narrative of deliberate starvation, and directly undermined its national interests and international standing.

Israel’s conduct has led to failure. This is now evident in the fact that Israel is perceived internationally as bearing sole responsibility for the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, even as it continues to deliver aid by air and land, without having secured a deal for releasing the hostages. The failure is strategic in nature and far exceeds the shortcomings of the GHF or any other aid mechanism. It stems from a narrow operational mindset focused on military maneuvering and a failure to respond to shifting realities on the ground—the collapse of order and deepening chaos in the Strip—with a comprehensive strategic vision.

A Forward-Looking Strategic Framework

Since the beginning of the war, Israel has aimed to dismantle Hamas’s rule, but it has done so without a comprehensive policy for the future of the Gaza Strip. This lack of a clear political vision has led to the adoption of tactical-operational solutions, such as the GHF.

However, tactical solutions for aid distribution do not address the core issue: the collapse of civil order and the transformation of Gaza into a lawless zone. As the war continues and chaos deepens, the humanitarian crisis worsens. In this reality, the gap between the humanitarian response and the actual needs of the population is widening, while humanitarian, operational, and political costs are steadily rising.

Using humanitarian aid as leverage against Hamas, amid collapsing order and growing chaos in Gaza, has proven a serious policy failure. It has contributed to worsening conditions on the ground and deepened humanitarian suffering. The consequences are already evident in the rapid deterioration of the humanitarian situation. Without acknowledging the deeper processes unfolding in Gaza, both Israel’s humanitarian efforts and its military achievements are being undermined and increasingly perceived in the international arena as ineffective and illegitimate.

Responsibility, however, does not lie solely with Israel. While Gaza’s humanitarian crisis is undeniably severe, the primary responsibility rests with Hamas, who thrive on civilian suffering. The lack of effective oversight within existing UN mechanisms has led to the collapse of the distribution system, severely undermining efforts to provide consistent and direct aid to Gaza’s population amid the many challenges of the ongoing war. Concealing the full range of drivers of Gaza’s humanitarian crisis—the deeper structural, operational, and governance failures—delays any meaningful solutions and reinforces the very dynamics that perpetuate the crisis.

In this reality, even if the war were to end tomorrow, humanitarian aid would still be at risk. Unless the root causes are acknowledged and addressed with a clear and enforceable framework, Issues such as looting, profiteering, and lawlessness will persist, rendering aid unsustainable and on the verge of collapse. Sustainable solutions, therefore, require a strategic framework that links immediate relief and scaling up humanitarian aid with long-term stabilization, supported by coordinated actions from key stakeholders.

For Israel, the primary challenge is to integrate military objectives within a coherent and coordinated civilian stabilization framework. The humanitarian efforts should be part of a comprehensive strategic framework that not only outlines how aid will be delivered but also identifies who will be responsible for restoring civil governance and order in Gaza. This framework must guarantee that aid channels are effectively insulated from Hamas, that civilians in need have secure and consistent access to assistance, and that humanitarian operations are consistently aligned with Israel's long-term political and security objectives.

The UN has a critical role in restoring the credibility of international humanitarian mechanisms. To achieve this, humanitarian operations must be shielded from political bargaining and institutional competition; the UN must uphold neutrality, ground its reporting in verifiable evidence, and avoid politicized narratives. Neutrality cannot excuse the actions of designated terrorist organizations; true impartiality distinguishes between a democratic state acting in self-defense and a terrorist group exploiting the suffering of its civilians. This will require addressing structural challenges posed by Hamas through implementing strict monitoring and transparent mechanisms that ensure it is excluded from distribution channels, enabling supplies to reach civilians without diversion. Acknowledging Hamas's responsibility does not lessen the urgent and worsening conditions faced by civilians in Gaza, nor does it absolve Israel of its role in the ongoing crisis. Instead, it places accountability where it belongs and creates the basis for rebuilding trust with Israel.

Furthermore, the UN should adopt a partnership-based approach by collaborating with credible regional actors, vetted humanitarian organizations, and independent oversight bodies to restore trust and improve efficiency. A credible UN must be prepared to engage with independent mechanisms, such as the GHF, which can help protect aid from exploitation and assist in enhancing the GHF's effectiveness and the integrity of humanitarian delivery.

Ultimately, the UN's credibility and its ability to ensure robust monitoring and oversight directly affect whether aid reaches civilians or is seized by armed factions, and whether humanitarian suffering is weaponized or serves as a pathway to stabilization.

The international community should enhance these efforts by providing political support, operational resources, and comprehensive monitoring to implement effective humanitarian measures. This involves encouraging the establishment of a legitimate governing authority in Gaza while avoiding unilateral actions. Recent announcements from several states regarding their intention to recognize a Palestinian state, outside a negotiated framework, strengthen extremism on both the Palestinian and Israeli sides. Such actions undermine the possibility of a genuine dialogue, reinforce political intransigence, and diminish incentives for compromise, while providing momentum to Hamas. Rather than resolving the conflict, they perpetuate it.

Instead, the international community should channel its efforts toward fostering a sustainable political framework, one that conditions progress on de-escalation and mutual restraint. This framework should curtail Hamas’s ability to exploit humanitarian suffering for political gain and empower moderate Palestinian actors willing to engage in serious negotiations.

Ultimately, only a coordinated, proactive, and forward-looking approach, grounded in broad and meaningful international cooperation, can provide a genuine response to Gaza’s population's urgent humanitarian needs and lay the foundations for a sustainable political order that will, hopefully, bring the war to an end.

____________________

[1] Fuel and gas counted in trucks, excluded from weight. | Source: COGAT.

[2] Supplemented with air drops since the end of July 2025.