Publications

INSS Insight No. 2093, February 4, 2026

The Board of Peace was initially conceived as a focused initiative intended to support the stabilization and reconstruction process in the Gaza Strip, as part of President Trump’s 20-Point Plan, which was anchored in the UN Security Council Resolution 2803. However, a review of its charter indicates a substantial deviation from its original purpose: the board is now defined as a global conflict-resolution mechanism outside the UN framework, with no reference to Gaza and no limitation to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. This gap between the board’s limited mandate and the broad authorities granted by the charter, together with its highly centralized structure, has drawn criticism regarding its legitimacy. As a result, major states have been reluctant to join the board, prompting questions about its ability to establish itself as a global conflict-resolution mechanism and about the implications this may have for the Gaza context.

The Board of Peace: From a Gaza Context to a Global Mandate

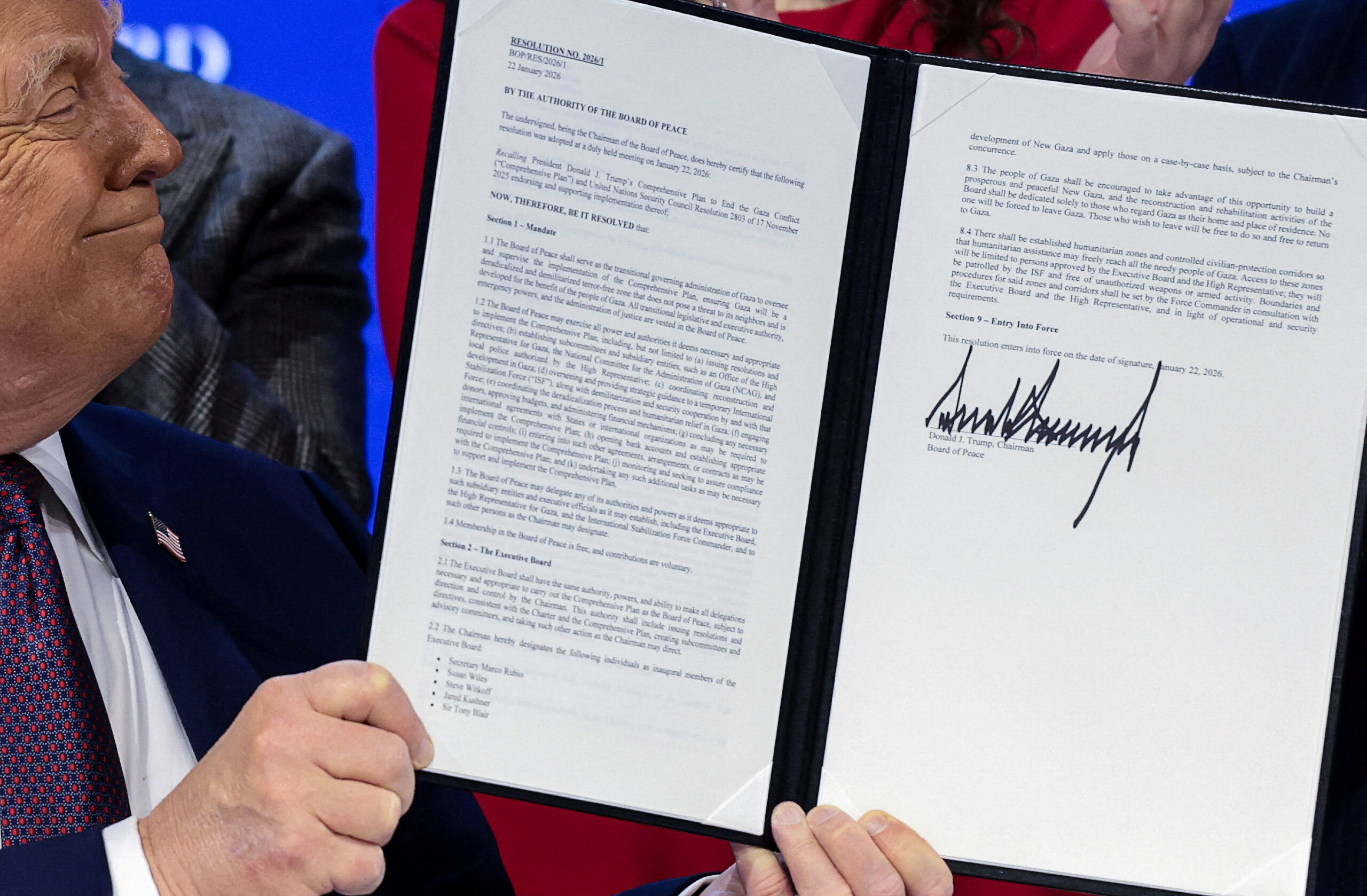

The Board of Peace (BoP) was established within the framework of President Donald Trump’s 20-Point Plan to end the war in the Gaza Strip. Presented in September 2025, it was intended to serve as a body for coordination and oversight of the plan’s implementation. The plan itself was anchored in UN Security Council Resolution 2803 of November 2025 and received broad international support, including from all Western states that welcomed the resolution.

However, the current version of the BoP, as presented at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2026, encountered reserved reactions and even firm opposition from many actors in the international community. This opposition stems from the discrepancy between the original, limited framework that was established for the board and the arrangements laid out in its charter, which exceed the mandate under which it was created, generate overlap and even institutional competition with the UN, and concentrate significant power in the hands of President Trump, who serves as the board’s chair.

First, critics argue that the establishment of the BoP in its current form constitutes an overreach of authority. Security Council Resolution 2803 granted the BoP a limited mandate to address the end of the conflict in the Gaza Strip within the Israeli–Palestinian context. In contrast, the charter expands the board’s mandate to serve as a global mechanism for conflict resolution outside the UN framework, without mentioning Gaza or referring to Resolution 2803. This expansion, in the absence of an additional Security Council resolution, is perceived as exceeding the BoP’s original mandate and the understandings that underpinned support for Resolution 2803.

In addition, the expansion of the board’s mandate is viewed as an attempt to establish an alternative, rather than merely a complementary, mechanism to the UN and its institutions, which were designated in the UN Charter as the central framework for maintaining international peace and security. Although the BoP’s charter does not explicitly mention the UN, it emphasizes the need to depart from “institutions that have too often failed” and to establish “a more nimble and effective international peace-building body.” In the eyes of its opponents, the BoP does not remedy the flaws of the international system but instead circumvents it, aligning with the Trump administration’s consistent policy of weakening the UN system, alongside withdrawals from key UN bodies and cuts in funding. This move has met principled opposition primarily from Western states, which view it as undermining not only the UN institution itself but also the multilateral international order that emerged after World War II and to which they attach great importance.

Criticism has also focused on the mechanism for selecting board members. The board’s charter grants President Trump exclusive authority to invite states to join, extend their membership, or expel existing members, as well as to establish, modify, or dissolve the Executive Board and other subsidiary bodies. Membership beyond three years is conditional on the payment of one billion dollars. According to critics, this creates a selective and unequal membership mechanism based on political, personal, and economic considerations. These features, along with the involvement of economic actors appointed by President Trump to the Executive Board, raise concerns about the injection of business interests and elements of corruption into the board’s activities.

Another concern relates to the concentration of power vested in President Trump as the chair of the board. The charter is drafted in a manner that fully subordinates the board to his authority. Although board decisions are adopted by a simple majority of member states, they are subject to the approval of the chair.

Furthermore, the charter enshrines the personal appointment of Donald Trump as chair of the board, independent of his continued tenure as president of the United States. Termination of his role is possible only through voluntary resignation or incapacity, as determined by a unanimous vote of the Executive Board. A succession mechanism is also established, allowing Trump to appoint his successor. Beyond the unconventional nature of such a personal appointment, the implication is that the board may not be led by a sitting US president, raising doubts about its standing and influence at that stage.

The International Community’s Response

As a result of these factors, the Board of Peace remains composed of a limited group of states. The vast majority of these states are non-democratic, and some are even rivals of Israel. Of approximately 60 states that received personal invitations from President Trump to join the board, only about 26 have agreed thus far. Among them are Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Turkey, Egypt, Jordan, Indonesia, Argentina, Hungary, and Bulgaria. Israel was also invited and accepted the invitation, although it did not participate in the signing ceremony in Davos. Russia and China, which were unenthusiastic about the board’s structure that would, in practice, subordinate them to President Trump, have not yet responded. It should be noted that President Trump rescinded Canada’s invitation following the speech delivered by the Canadian prime minister in Davos, criticizing US conduct on the international stage, underscoring the role of personal considerations in decisions regarding membership.

In contrast, most Western states have declined the invitation to join the Board of Peace, including the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Germany, and Italy. These states supported Trump’s 20-Point Plan and Resolution 2803, which served as the basis for establishing the board, largely because of Trump’s ability to bring about a cessation of hostilities and Europe’s interest in stabilizing the Gaza arena. However, they are unwilling to join a board whose mandate exceeds the original understandings and whose characteristics are perceived as problematic. Their refusal underscores a reluctance to align with the US administration and to confer legitimacy on a global mechanism perceived as circumventing the multilateral international order. UN engagement with the BoP is also expected to remain strictly confined to the implementation of Trump’s Gaza plan, as authorized under Security Council Resolution 2803. Accordingly, in the absence of support from additional permanent members of the UN Security Council and without significant backing from leading democracies, the traditional allies of the United States, the BoP’s international legitimacy is undermined, and its ability to establish itself as a global mechanism is constrained. This position draws a clear boundary against attempts to expand the board’s mandate beyond the Palestinian context, highlighting the depth of the dispute surrounding its future.

Implications for Israel

Israel’s decision to join the board was expected, given the nature of its ties with the Trump administration and the board’s direct impact on Israel’s core interests. In addition, the board is preferable for Israel to UN bodies, which have routinely adopted anti-Israel positions over the years, and it may serve as a counterweight to international frameworks perceived as restrictive, even if it does not become a true alternative to the UN.

With respect to the Gaza Strip, Israel’s participation in the board grants it influence over the design of security arrangements and governance mechanisms while seeking to reduce operational-security risks and maintain a direct coordination channel with Washington. However, the composition of member states and the inclusion of countries problematic from Israel’s perspective, including Turkey, Qatar, and even Saudi Arabia, could lead to Israel’s isolation in decision-making processes and generate political pressure on sensitive issues, including freedom of military action, the lines and timing of the IDF’s withdrawal, the implementation of demilitarization, and the reconstruction framework. This risk is heightened when gaps emerge between Israel’s positions and those of the United States.

Beyond decisions related to the Gaza Strip, should the Board of Peace expand its activities to other conflicts relevant to Israel, such as escalation with Syria or Lebanon or another regional actor, its actual influence on Israel remains unclear. Given Israel’s dependence on the United States, it is expected to continue aligning with President Trump’s positions, with him remaining the decisive actor within the board. At the same time, the existence of an additional multilateral mechanism alongside UN bodies could constrain Israel’s diplomatic freedom of action and limit the advantages and flexibility of bilateral conduct.

This difficulty is sharpened by the board’s composition, which includes regional states whose interests diverge from Israel’s. In situations where shared economic or strategic interests develop between these states and the United States, Israel could find itself isolated within the board and subject to pressures or decisions that do not align with its positions. The absence of major Western states, including Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom, further weakens Israel’s ability to build an internal counterweight within the board, even in cases where its interests clearly overlap with theirs.

Moreover, Israel’s participation in the board places it alongside Trump and in a grouping with states regarded as less democratic, further distancing it from Western countries.

Implications for the Implementation of the Plan in the Gaza Strip

The BoP serves as the overarching body directing all mechanisms designed to implement the demilitarization and reconstruction plan for the Gaza Strip, including the Gaza Executive Board (GEB); the National Committee for the Administration of Gaza (NCAG), composed of Palestinian technocrats; and the International Stabilization Force (ISF). Against this backdrop, the question arises as to how the erosion of the board’s broad legitimacy as a global body may affect the implementation of the Gaza-specific plan.

From the outset, the 20-Point Plan drew widespread public and political criticism for framing the Gaza conflict primarily as an issue of management, security, and economic reconstruction while sidelining the political-national dimension of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and lacking an agreed-upon political horizon. This criticism intensified following the unveiling of the reconstruction plan presented by Jared Kushner in Davos, which critics described not only as “detached from reality” but also as serving external business interests at the expense of the Palestinian population. The absence of major Western states from the BoP further complicates efforts to establish international legitimacy capable of mitigating this criticism.

With regard to cooperation in the implementation of the plan itself in Gaza, the situation remains unclear. The Western states’ decision not to join the BoP does not necessarily mean disengagement from Trump's 20-point plan for Gaza, given their continued interest in mitigating the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, stabilizing the area, and preventing regional escalation. At the same time, there is concern that overly close cooperation with the BoP could be perceived as legitimizing its broader model, which they view as circumventing the multilateral international order. Moreover, success in Gaza could set a precedent that strengthens the board’s standing and encourages expansion into other arenas, a scenario that Western states seek to prevent.

Under these circumstances, Western involvement is likely to remain limited and selective, focused on concrete humanitarian and infrastructure projects, conducted primarily through existing UN channels, while avoiding integration into broader implementation efforts. In the short term, however, the absence of Western states from the BoP should not significantly affect the operational execution of the plan, given that they were not intended to play a central role in the core implementing bodies or to be the primary source of financing.

In the medium to long term, however, the BoP’s contested standing creates uncertainty and could affect the plan's implementation. Failure in Gaza would likely deepen international criticism and further reduce states’ willingness to support the board, while success may generate only partial legitimacy that is difficult to sustain. Accordingly, although the implications of international rejection are not immediate, they cast a heavy shadow over the BoP’s ability to deliver a stable and sustainable process in the Gaza Strip, particularly in the period following President Trump’s tenure.

Conclusion

President Trump’s Board of Peace reflects an attempt by the Trump administration to create an alternative mechanism to the UN for conflict management, but it is built on limited international legitimacy and a centralized, personalized institutional structure. The decision of leading democracies to refrain from joining the board does not reflect a narrow tactical disagreement but rather a rejection of the board’s legitimacy as a global mechanism beyond the Palestinian context.

In the short term, this weakness is unlikely to fundamentally disrupt the implementation of the components of the 20-Point Plan for Gaza, which rely primarily on the United States, regional actors, and operational execution mechanisms. In the medium to long term, however—particularly given the BoP’s highly personalized nature and its reliance on President Trump—the erosion of its legitimacy may reduce political and financial support from states, weaken enforcement capacity and implementation mechanisms, and increase the risk that the board’s failure or gradual decline will eventually reassign responsibility for the Gaza Strip to Israel, whether in practice or in international perception.