Strategic Assessment

Relations between China and the United States during the four years of the Joe Biden administration were characterized by constant efforts to prevent escalation and by American adoption of the “Chinese approach,” which maintains that discussion of contentious issues should be minimized, while instead focusing on areas where cooperation is possible. These efforts succeeded in preventing significant crises in relations, the biggest of which was the visit of Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan, and the shooting down of the Chinese espionage balloon in US airspace, from escalating to direct super-power or regional clashes. Moreover, these crises drove the emergence of a mechanism of strategic coordination and a series of high-level meetings. This paper analyzes the issues that comprised the core of relations during these four years and examines how, despite growing tensions in each case, the superpowers managed to avoid confrontations that would undoubtedly have had huge impacts on the entire world.

Key words: China, United States, President Biden, President Xi, strategic mechanism, regional disputes, superpower rivalry, diplomatic crises, diplomacy

Introduction

China presents the most important foreign policy challenge for the United States, and it has many facets, among them, diplomatic, economic, and military. Contrary to almost every other issue, it appears that both Republicans and Democrats in the United States view China as a challenge to the undisputed international standing of the U.S. since the end of World War II. The U.S., therefore, invests copious resources in its efforts to achieve an advantage over China in a range of areas, while simultaneously pursuing cooperation with it.

The first Donald Trump presidency is remembered mainly for his trade war with China, leading to incidents of low-intensity friction with the second-largest power on the planet. Thus, at the end of Trump’s first presidency in 2020, relations were at a low ebb.

The tension between the two superpowers did not ease when Biden was sworn in as US President, nor during his term, although he was considered less hawkish than his predecessor. In addition, during the four years of the Biden Administration, there were substantial crises in relations, although the relations nevertheless remained stable, and escalation and loss of control were avoided. The question arises: How, despite numerous significant crises, did the two powers maintain functioning relations, and what methods were used to manage the disputes between them and with their respective allies.

China and the United States have different approaches to managing disputes, which are underpinned by opposing interests and different core values. China prefers to manage disputes and tensions rather than solve them (Evron, 2015), with the stability of allied regimes at the top of its list of priorities, as this approach helps it to continue profiting from relations with them (Sun & Zoubir, 2017). Sometimes China tries to influence the situation via multilateral forums such as the UN, while exploiting the platform to criticize American failures (Evron, 2015). China’s tactics were well summarized by Wang Peng, President of the Chinese University for Foreign Affairs, which is subordinate to the Foreign Ministry, when he said that “Sharing in both prosperity and sorrow creates a sense of brotherhood of interests […] It rises above the mentality of a zero-sum game of traditional geopolitics; a search for common ground while deflecting disputes” (Kewalramani, 2025).

The American approach to handling crises is very different from the Chinese approach. The United States attempts to resolve disputes and work towards sustainable agreements. It also often appoints a special envoy to a region to address crises directly. The American approach encourages the parties to sign peace treaties, and the American mechanism encourages direct dialogue at various levels on matters under dispute (U.S. Department of State, n.d.).

Despite the crises between China and the United States during the Biden administration, the two countries developed a mechanism of consultation and dialogue that operated above and below the surface, even when mistrust between them was very high. The purpose was to avoid escalation. In order to examine the mechanisms used by the superpowers to minimize tensions, this paper analyzes the content of official statements published after meetings between the parties throughout the Biden Administration period, as well as the issues discussed at those meetings and their frequency, to identify ideological trends and rhetorical patterns. This method of analysis helps us not only understand the frequency with which various matters were discussed but also to assess their importance in the web of inter-power relations, and the way in which Chinese and American policies were formulated and revised over the four years, to understand the contexts in which tension-reducing mechanisms were employed.

The analysis of these sources revealed that both superpowers used relatively conciliatory rhetoric towards one another, enabling them to lower the flames and create an image of normality even in times of tension. Some will say that the United States adopted the Chinese approach, which seeks shared opportunities, pursues joint gains (win-win), and disregards problems, rather than the American tendency to pursue direct dialogue on matters of contention. Adopting this approach enabled them to overcome crises with relative success. This paper examines why the superpowers chose the Chinese method of crisis management, and when and how this approach was evident in the course of the Biden Administration.

Areas of Friction and Responses

The beginning of Biden’s presidency was characterized by a series of incidents between the United States and China and by efforts to create mechanisms to prevent further deterioration in relations until a measure of calm was achieved. The frictions that shaped those four years included the visit by the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, to Taiwan, the Chinese espionage balloon that was discovered floating above the United States, and critical global crises such as the war between Russia and Ukraine, and between Israel and Hamas. All these crises took place in the shadow of an end to the coordination between the superpowers in various aspects in the first half of the Biden presidency.

The tension between China and the United States at the beginning of Biden’s tenure was particularly noticeable when senior officials from both governments met in Alaska in March 2021, some two months after the new administration entered the White House, for three marathon rounds of talks that lasted two days. As evidence of the talks’ importance, both sides sent senior representatives: China sent Foreign Minister Yang Jie-Chi, and the US sent Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan (BBC News, 2021a).

Notwithstanding the good will, the talks were rather acrimonious. On the first day, the Chinese delegates accused the American delegates of “arrogance and hypocrisy” (Jakes & Myers, 2021), while the Americans accused the Chinese of “an attack on basic values” (CNA, 2021). The summit ended after two days, without the conventional joint statement, but after both sides had expressed their concerns and positions on the issues central to them: China on interference in its domestic affairs, the “One China principle”, sanctions and Cold War mentality; and the United States on Taiwan, human rights, espionage and Chinese military actions against US allies. Although this meeting could have set a combative tone for relations between the superpowers under the new administration, in effect, the foundations were laid for a consultation system. This was only the first, albeit unpleasant, step towards the establishment of tension reduction mechanisms that lasted throughout Biden’s term.

In the following months, relations continued to deteriorate gradually, while the US made several moves that China perceived as challenging and adversarial: In June 2021, some two months after the tense Alaska summit, Biden encouraged the leaders of NATO and the G7 who were meeting in Britain, to condemn China on human rights infringements that US delegates had raised at the meeting in March but were dismissed by their Chinese counterparts (Collinson, 2021). China responded angrily to Biden’s actions, and its embassy in the UK published a statement that “the G7 group of nations is exploiting issues relating to Xinjiang in order to engage in political manipulation” (AFP, 2021). Three months later, the AUKUS alliance was formed by Australia, Britain, and the United States. Its declared purpose was “to promote a free and open Indo-Pacific that is also safe and stable,” but apart from cooperation among its member states on various matters, including the development of weapons systems, most of the media coverage on the subject dealt with the fact that Australia intended to purchase nuclear submarines. China viewed this development as dangerous and opposed it (BBC News, 2021b). The American invitation of Taiwan to participate in the democracy summit (Pamuk, 2021) and the Pacific Rim exercise, the world’s largest marine military exercise, run by the American Navy (Everington, 2021), also soured relations between the US and China.

China did not remain indifferent to these steps and adopted countermeasures to express its displeasure with what it perceived as American aggression and escalation of tensions. After the Pacific Rim exercise, China stepped up its military activity in the Indo-Pacific region and conducted the first joint patrol with the Russian Navy in the Japan Sea (Xuanzun & Yuandan, 2023), at a time when “Western countries are building hostile regional security organizations such as the Quad and AUKUS” (Xuanzun & Yuandan, 2021). Additionally, China tightened its export restrictions and worked on improving its global position by accelerating Chinese technological development. The Chinese government set itself an ambitious target of increasing its R&D funding by over seven percent each year from 2021 to 2025, in order to reinforce its status on innovative technologies such as artificial intelligence, semiconductors, and quantum computing (Yao, 2021). In February 2022, a few days before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, China and Russia announced that their relationship was to be framed as a partnership without borders, condemned the AUKUS alliance, called for an end to NATO expansion, and expressed shared concerns over the American plan to deploy missile defense systems in various parts of the world (Reuters, 2022).

The increasing tensions between the superpowers following the establishment of AUKUS and the Pacific Rim exercise were dwarfed by two crises, the first in July 2022 and the second in February 2023, which confirmed each party’s worst fears.

China, which is wary of American interference in what it perceives as its internal affairs, particularly the Taiwan issue, woke up in July 2022 to an announcement by Member of Congress Nancy Pelosi, at that time Speaker of the US House of Representatives, of her intention to visit Taiwan as part of a tour of several countries in East Asia. The Chinese government tried to pressure and threaten to have the visit canceled. Some in the American administration even joined in to pressure Pelosi, indicating an attempt to reduce the level of tensions, but to no avail. The visit took place in August of that year. It drew a barrage of complaints from the Chinese government, which took the very unusual step of cutting ties with the American administration, including military coordination on the prevention of mis-calculation (2022, Herb & Cheung), and of embarking on its biggest-ever military exercise around Taiwan (Plummer, 2022).

About six months later, it was the turn of American concerns over Chinese espionage to be realized when a Chinese balloon was observed floating over Alaska, western Canada, and the United States mainland. The balloon was shot down a week later over Southern California and sent to the FBI laboratory for examination. American fears were confirmed when it was discovered that the balloon carried data-collection equipment and even American technology (Tatlow, 2025). However, the information it collected was apparently not transmitted to China (Kube & Lee, 2024). The incident shook the administration. The former US Ambassador to China, Nicholas Burns, said in an interview that “after the balloon incident […] I think that this was the most tense moment […] between the world’s two strongest military powers” (WSJ, 2025). Perhaps Burns’ concern was heightened by the fact that, following this event, China decided to cut off the few channels of communication between senior officials that remained intact after the Pelosi crisis.

Secretary of State Blinken tried to play down the incident in order to rescue his visit to Beijing, planned for the following week, and thereby protect the already fragile relations, but following media coverage and social media attention on the incident, he was forced to postpone the visit (Pamuk et al., 2023). Despite the potential for escalation, both sides chose to minimize the seriousness of the event and avoid stronger rhetorical or diplomatic reactions. Biden called the incident “a small breach” that was done unintentionally and was embarrassing for the Chinese government, which did not apparently intend to spy on the United States (Yousif, 2023). The weak American response, which did not reflect the administration’s great concern, shows that the Americans had decided to conduct their foreign policy in an unexpected way. Instead of harsh condemnations, they opted to lower the tone and try to conduct the discussions with China behind the scenes.

At first, the Chinese also tried to minimize the incident, claiming that it was a civilian balloon engaged in research and meteorological work. Unusually, the statements coming from Beijing were almost apologetic in nature, and the Chinese authorities even said that they “regretted the aircraft’s unintentional entry into American airspace due to force majeure” (Wong & Wang, 2023). After Blinken canceled his planned visit and the United States shot down the balloon, China changed its tone. A spokeswoman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry accused the Americans of “over-reacting” and called the interception “unacceptable and irresponsible” (Wong & Wang, 2023). However, notwithstanding the severe condemnation from the Ministry, China did not condemn the interception at the UN. The responses of both China and the United States illustrate the way in which, at this stage, the parties chose relatively conciliatory rhetoric and preferred cautious crisis management over conflict escalation.

Reducing Tensions

Despite his government’s almost apologetic response to the balloon incident, Wang Yi did not expect the United States to aggravate the crisis (Magnier & Wang, 2023), with the hope that it would not irreversibly harm the countries’ relations. A few months later, in mid-2023, the tone of both countries changed, and there was a real effort on both sides to improve relations and downplay the tensions by activating existing and new channels of strategic communication. This trend continued for quite some time and eventually stabilized relations between the powers.

The first meeting that took place in this context was between Foreign Minister Wang Yi and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, in the framework of what was later called the strategic channel. The statement published by Chinese state media after the meeting, which was intended to establish firm ground for the relations, shows the importance attached by the Chinese to the stabilization of relations and the clarification of the Chinese position on the issues of Taiwan and the Indo-Pacific, and the Russia-Ukraine war (Delaney, 2023). These topics were raised regularly during meetings between the parties.

The meetings remained within the limits of purely strategic discourse, with no substantive change in either Chinese or American policy. For both parties, the purpose of the strategic channel and the diplomatic meetings was to stabilize relations and create an appearance of calm. Both sides knew that the meetings were not intended to resolve their various disputes. The strategic channel laid the groundwork for a change in the United States’ approach, as shown by the gradual adoption of the Chinese approach to conflict management, which focused on shared interests and ignored or sidelined disputes. This approach enabled both sides to respond solely through diplomatic means, without taking any actual steps or changing their policies. In certain cases, the US delegates even refrained from raising disputed issues at formal meetings, as part of an effort to maintain stability and prevent escalation. This conduct helped both sides manage tensions, stabilize relations, limit overt friction, and sideline sensitive issues.

Communication Between the Powers

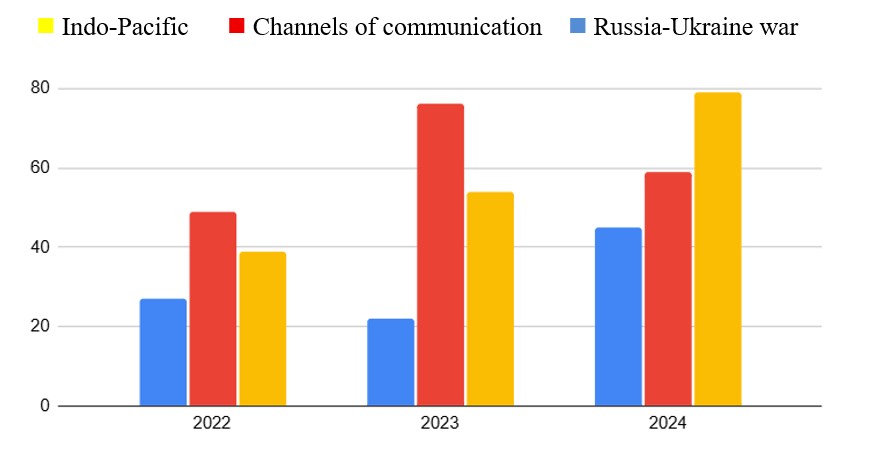

Communication and discussions between the superpowers continued throughout the four years of the Biden presidency. In the first year, they were far from a top priority, but in 2022, following Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan and the resulting deterioration in relations, the various aspects of such communication—military, economic, and in UN forums and initiatives—, became a central subject of discussion. Although there was a great deal of talking, there was no real breakthrough in the establishment of stable mechanisms for coordination, and communication between the parties remained context-dependent. In 2024, regular contact declined in importance, although the number of discussions on military communication quadrupled, perhaps due to the tension in the South China Sea and the need to avoid escalation. That year, it became clear that the parties had chosen to manage their disputes through dialogue rather than by taking concrete steps to reduce each other’s military presence or by setting clear rules of conduct, such as patrols in the South China Sea.

As already mentioned, in order to renew their communication, China and the United States established a strategic channel of communication led by Wang Yi, the Chinese Foreign Minister, and Jake Sullivan, the American National Security Advisor. The first seeds of this channel were sown at a Xi-Biden meeting in Bali, Indonesia, in November 2022 (Sevastopulo, 2024), leading to a series of important meetings between officials from the two countries at various levels of seniority.

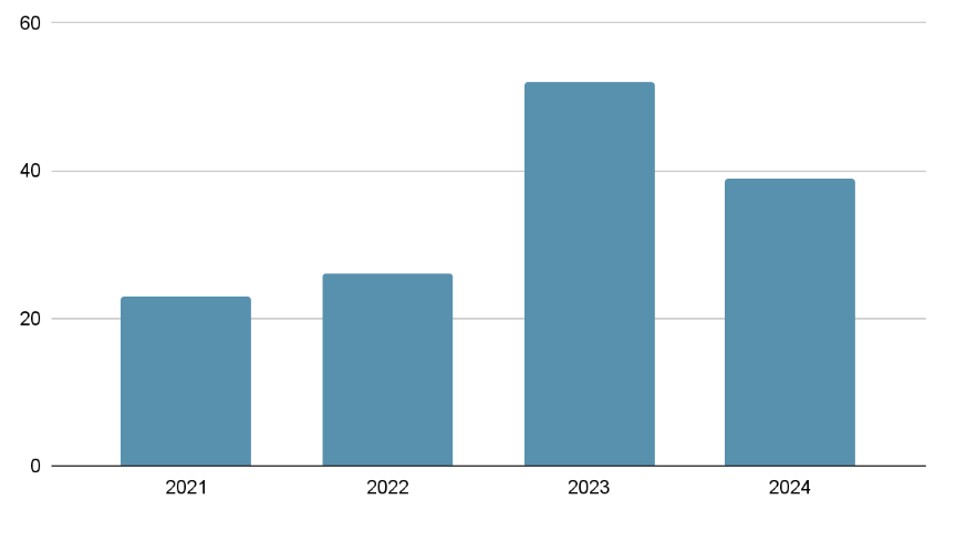

Apart from the meetings between Wang and Sullivan, other senior diplomatic officials held meetings, some on the margins of international summits and forums such as ASEAN and the International Trade Organization, and others on the soil of one of the powers, both in the US and in China. These constituted the majority of meetings that year, although there were also a few telephone calls and video calls at various levels. The large number of meetings shows that the parties had decided to prioritize diplomatic discourse (52 meetings that year, compared to half that number in other years) to stabilize relations, even though vast disagreements remained. Such a development is desirable but certainly not inevitable, since each superpower could have chosen escalation and more forceful ways to extract concessions from the other superpower, or could simply have neglected the maintenance of relations and let them deteriorate.

Number of meetings between the parties by year

Source: Authors’ data

The climax came when 2023 ended with a meeting between military commanders of the two countries, a meeting that had not taken place since the rift between the sides’ security establishments following Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan. No other concrete steps were taken to rebuild military trust. This reinforces the impression that the purpose of the meetings between senior Chinese and American officers was to establish a mechanism to ease tensions while adopting the Chinese approach of managing disputes and sidelining friction, with an understanding that the main points of disagreement remained unchanged.

The most senior members of the administrations, Presidents Xi and Biden, met three times over these four years and spoke by telephone or video twice more. Each president has his own rhetorical style, but they strove to achieve the same goal: collaborating wherever possible, avoiding discussions of controversial matters or overly strong statements that could lead to escalation. In general, while Biden preferred to adopt a practical tone, paying direct attention to areas where the powers could cooperate, President Xi chose dialogue based on ideology. At their very first encounter Xi defined three principles and four matters that should form the basis of the relationship; at the second, he told Biden about internal social processes in China and about the history of Taiwan; at the third he spoke of modernization; at the fourth his topic was his vision for their relationship; and at the last meeting he summarized the lessons to be learned from relations between the countries.

President Xi used the final meeting to send a message to the next American administration, setting out the “four red lines” that he said “must not be challenged or crossed”: the question of Taiwan, democracy and human rights, “China’s system and path” (its system of government), and China’s right to development (Xinhua, 2024b). Bringing these four issues together revealed what was really worrying President Xi: American interference in matters that he perceives as internal Chinese affairs. This includes Taiwan, which for him is a rebellious Chinese province, the Chinese style of government and its attitude to opponents and ethnic minorities, or China’s economic agenda and its manufacturing capabilities. Xi’s red lines underscored his attempt to remain within recognized boundaries and perhaps also avoid contentious ones, such as the South China Sea. China was certainly not ready for the United States to conduct military activity in the region. Still, Xi avoided mentioning this subject and stuck to less controversial matters, in which the status quo was not expected to change. Despite their different styles, neither president was ready to take blatant political steps, and even when the mutual statements included warnings about red lines, they remained within the limits of conciliatory discourse. Both sides were careful not to threaten concrete actions or to take substantial measures, even on subjects in dispute. This conduct reinforces the general picture: rhetorical handling of tension while avoiding actual escalation, in accordance with the Chinese approach.

Regional Conflicts

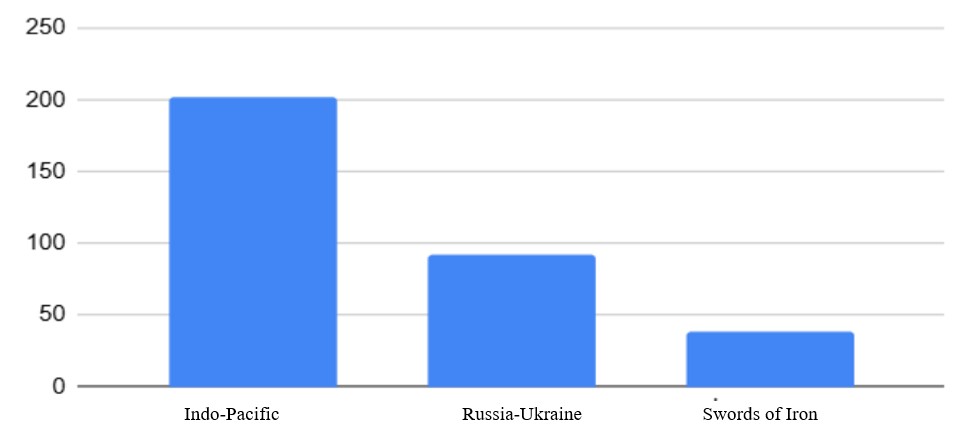

During Biden’s presidency, regional conflicts were discussed roughly 400 times, accounting for 86.33 percent of all meetings. This category includes talks on Taiwan, the Russia-Ukraine war, and the Israel-Hamas war. When Russia invaded Ukraine in January 2022, the war in Europe became the focus of talks between the parties. However, in 2023, the focus of talks on regional conflicts turned to tensions in the Philippines and to the Israel-Hamas war. This trend shows the importance of both direct and implicit discourse on regional matters, while maintaining the dominance of regional disputes in which China and the United States were involved either directly or indirectly. Despite their importance, the exchange of views remained largely rhetorical. The United States adopted the Chinese approach to conflict management and refrained from accusing China of fueling tensions in these arenas, although it had increasing evidence of Chinese activities in areas of tension such as Taiwan, Ukraine, and Israel.

The Taiwan Issue

This was the only subject raised by both parties at every discussion between President Biden and President Xi, as each country firmly asserted its position and stuck to its policies. At every meeting, China emphasized that the Taiwanese issue was crucial to relations between the superpowers and constituted a red line, the infringement of which was unacceptable. Beijing frames its attitude towards Taiwan according to the “One China principle,” whereby the Chinese Communist Party is the sole legitimate government on both sides of the Strait. The U.S., however, recognizes the “One China policy,” which has meaningful implications for China’s claims and Taiwan’s status. However, throughout the period, the United States continued to walk the tightrope and express a dual position, which, on the one hand, recognizes China as the legitimate and sole representative of both China and Taiwan, but on the other hand maintains elaborate contacts with Taiwan, including significant trade in weapons, to China’s displeasure.

Number of mentions of regional conflicts in China-US talks, 2021-2024

Source: Authors’ data compiled from official statements issued by the US and China

At the Presidents’ first encounter in November 2021, which was a virtual meeting due to the Covid pandemic, the President of China accused Taiwan of seeking American support in its quest for independence, and even implicitly threatened his US counterpart when he said that American cooperation would be “very dangerous, like playing with fire, and anyone who plays with fire, gets burned” (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China, 2021). Despite the centrality of the issue for both superpowers, neither China nor the US translated their statements into actions, and it seems that raising this subject at every meeting amounted to little more than paying lip service, with no attempt to alter the status quo. The presidents mentioned the subject, but there were no harsh mutual accusations nor expressions of interest in increasing military activity. Throughout the period, aircraft and ships of the People’s Liberation Army continued to cross the halfway line in the Taiwan Strait without arousing any notable American reaction, notwithstanding strong statements and American policy that vigorously objected to increasing tensions in the Strait. It appears that the Biden administration chose to adopt the Chinese approach, seeking to minimize its disagreements with China rather than settle them through significant diplomatic or military moves.

Mentions of various subjects in discussions between the powers, 2022-2024

Source: Authors’ data compiled from official statements issued by the US and China

The Russia-Ukraine War

The Russia-Ukraine War put China and the United States on opposite sides of a conflict in Europe, but once again, they chose not to escalate any disagreements with their allies. While China called again and again for “a just, lasting and binding peace agreement” in Ukraine (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2025), and President Xi even suggested to President Biden that NATO countries should conduct a dialogue with Russia (Shala et al., 2022), behind the scenes the Chinese Foreign Minister told European leaders that China did not want to see Russia lose in Ukraine, because it feared that the United States would turn its attention to China after the war (Bermingham, 2025). Contrary to China’s conciliatory public statements, the United States declared its support for Ukraine and its opposition to the Russian invasion, even attempting to form a pro-Ukraine Western coalition (Clark & DOD News, 2024). Despite their opposing positions, the countries remained committed to maintaining the cautious dialogue established before the war broke out.

Two days before the invasion, the subject was discussed in a telephone call between Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Wang stressed that “all parties must act with caution and seek to resolve the crisis through dialogue.” In contrast, Blinken stressed America’s “unwavering support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity” (Ng, 2022), but did not ask China to utilize its new status as Russia’s “partner without borders” to halt the incursion into Ukraine.

One month later, the two leaders conducted a virtual meeting, which showed signs of a more resolute American approach. A summary of the discussion released by the Chinese side stated that “President Biden explained the United States’ position and expressed readiness to communicate with China to prevent a deterioration of the situation” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2022). By contrast, the American announcement stated that “President Biden described the consequences for China if it supplied material support to Russia while it was carrying out brutal attacks against towns and civilians in Ukraine” (The White House, 2022a). President Biden spoke even more harshly to President Xi, but no threat materialized. The United States placed its first sanctions on Chinese companies that assisted Russia in its war in Ukraine, only at the end of 2024 (Tang, 2024b). However, despite Biden’s stronger statements, this conversation reflected a dynamic of cautious dialogue, notwithstanding the significant gap between the parties. Each side stressed its position without descending into open diplomatic conflict. This rhetorical choice could be evidence of both parties’ wish to avoid controversy where it was clear there could be no agreement, due to their shared interest in preventing escalation, even in the case of extreme disagreements with far-reaching consequences.

Throughout the Russia-Ukraine war, China and the United States continued this trend of managing tensions rather than seeking solutions, and their discussions of the war gradually declined. In 2023, there were fewer mentions of the war, even though the superpowers were at the height of their marathon of meetings, and the Ukraine issue remained at the heart of American foreign policy. During those months, further evidence of Chinese aid to Russia accumulated, but the Biden administration downplayed its significance by focusing on Ukraine’s rights rather than on Russian aggression and the Chinese aid that enabled Russia to operate continuously (The White House, 2022b).

The dwindling references to the war and American statements indicate that both sides had adopted the Chinese approach to crisis management. China intentionally pushed the issue to the fringes of the agenda, without publicly supporting those who declared they shared a “partnership without borders,” but also without condemning them. The United States, for its part, reiterated its position in a clear and determined manner but avoided direct escalation against China, even when it had information that China was aiding the Russian war effort. It also avoided an intensive debate on the issue, which would have required it to raise the issue of Chinese aid to Russia.

The Middle East and the Swords of Iron War

Another area of tension during the period under discussion was the Middle East. Although this region did not involve direct conflict between China and the United States, that does not mean there was no competition between the parties; instead, all tension was channeled via third parties, i.e., they competed indirectly. In this sense, the Middle East has been a focal point of the struggle for influence between the superpowers during Biden’s presidency.

The Swords of Iron War erupted when thousands of Hamas terrorists infiltrated southern Israel, completely eroding any trust between Israel and the Palestinians. Therefore, there was little chance for a dialogue to be mediated by China, which Israel, anyway, perceived to be biased against it. The war also quickly became another indirect platform for the diplomatic struggle between China and the United States. Chinese policy focused on economic development in the region and maintained economic and diplomatic ties with Israel, while also severely criticizing both Israel and the United States on the international stage (Ben Tsur, 2025). Unlike China, the United States stood beside Israel almost without reservations and gave it diplomatic and military support. On this matter too, despite the opposing positions and actions of the two superpowers, the tension did not lead to a deterioration in relations. They rarely mentioned Israel and the Palestinians in their discussions and ignored the war almost completely.

The United Nations Security Council, of which both countries are members with veto power, is the main arena where China and the US censure each other, during the Swords of Iron War and more broadly. There, they conduct a kind of “clash of declarations.” Both countries have proposed resolutions relating to the war to this important forum, and each has vetoed the proposals of the other. China explained its use of the veto against an American proposal, stating that Israel had the right to defend itself (Magid, 2023) by claiming that the proposal did not call for a ceasefire or an end to the fighting. According to the Chinese UN Ambassador, the American proposal was “extremely unbalanced and confused right and wrong” (Permanent Mission of China, 2023).

The US vetoed a Chinese proposal in the UN Security Council that called for a ceasefire, maintaining that it failed to condemn Hamas (Lederer, 2023), which naturally led to Chinese protests. Such criticisms were not only raised when parties exercised their veto in the Security Council, but also at key moments during the war, highlighting the rhetorical and ideological gap between the sides. A year after the war began, Geng Shuang, Deputy Chinese Ambassador to the UN, strongly condemned the United States: “Without the repeated defense of one side by the United States, many resolutions of this Council [the UN Security Council] would not have been so blatantly rejected or breached,” adding that the US should use its influence to “pressure Israel to stop its military action without delay, as required by Council resolutions, and give the Palestinians who have suffered for so long a chance to live” (Khaliq, 2024). These pronouncements from the Chinese representative, harsh as they were, had no effect on diplomatic relations between the US and China, such as breaking off or limiting dialogue between them, of which China had previously shown it was capable, and were not expressed directly to the American delegates but only via the UN platform (U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, 2024; Xinhua, 2024a).

Formal dialogue between the powers on the war also took place outside the UN, although it was more limited. China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi spoke several times with his American counterpart, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, and with Biden’s National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan. Just one week after the war began, on October 14, 2023, Wang expressed to Blinken the need to convene an international peace conference to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (Consulate General, 2023). That same week, Wang told his American counterpart that “the immediate preferences are to achieve a ceasefire and a reduction of tension, in order to avoid exacerbating the humanitarian crisis” (Xinhua, 2023).

Contrary to the Chinese declaration, the White House statement said that the United States had spoken to China in the framework of diplomatic contacts on behalf of Israel, and the American Secretary of State told his Chinese counterpart that Hamas must cease its attacks and release the hostages (U.S. Department of State, 2023). Both announcements could be interpreted as genuine efforts to cooperate and end the war, but they remained merely diplomatic gestures that did not reflect a genuine commitment to solving the problem.

When Washington suggested to China that it join its multilateral task force to act against the Houthis’ threat to shipping routes, China refused (Van Staden, 2023), even though Chinese ships also benefited from free and safe passage through the Bab El-Mandeb Straits, and most of the cargo involved originates in China. This refusal symbolized not only China’s reluctance to join an initiative led by the United States but also its general tendency to avoid military interference in disputes in other parts of the world and its preference to allow the United States to act as the global policeman, thus saving itself unnecessary risk and cost. This is a rare case in the course of relations between the countries during the Biden presidency, in which the US sought to return to its traditional method of solving crises, trying to reach a solution. China did not cooperate with the American attempt, and rather than responding with threats or anger, the US acquiesced.

US support for Israel is continually expressed in actions, including frequent visits to Israel by senior American officials, sending aircraft carriers to the region in response to threats from Iran, and the famous speech in which US President Joe Biden warned against the opening of additional fronts against Israel. Not only did all this once again show the Chinese that Israel was deeply embedded in the American-Western “camp,” but also, contrary to the theory they had tried to construct over the preceding years, that the United States had not retreated from the Middle East. If their theory had proven correct, it would have helped Beijing portray the US as an unreliable ally and draw the Gulf States closer to itself, and perhaps even Israel, albeit to a lesser extent.

In response to what China perceives as the U.S.’s unambiguous siding with Israel, Beijing attempts to present itself as “neutral” and therefore not supporting either of the warring sides. It believes that this perception allows it to criticize the United States for what it sees as a morally defective stance and double standards. In addition to tarnishing America’s reputation, these claims are used by Beijing to refute allegations against it made by Western countries, led by the United States. At the same time, China is also interested in differentiating itself from its Western counterpart. While Washington is seen as supporting developed Western nations, China wishes to exploit the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and other geopolitical developments to position itself as the representative of developing countries.

Conclusion

Before Biden’s inauguration in January 2021, relations between China and the United States were very tense. During the next four years, the relationship experienced many more upheavals, both big and small, culminating in the visit by the Speaker of the US House of Representatives to Taiwan and the Chinese balloon found floating above US territory. These and other incidents during the Biden administration had the potential to increase tensions between the powers and cause considerable damage to their relations. This negative outcome was apparently avoided due to a decision by both governments, the Chinese and the American, to maintain low tensions through regular dialogue at the highest levels, while focusing on areas where cooperation was possible rather than on areas of friction and disagreement. This decision, which can be characterized as embodying the Chinese approach, was expressed in both rhetorical and practical ways. In rhetorical terms, senior officials on both sides, including the superpowers’ presidents, tried to interact in ways that encouraged cooperation and reduced the negative consequences of crises.

In practical terms, most of Biden’s term in office was characterized by an intensive series of meetings between senior Chinese and American officials, intended to build and strengthen mechanisms of consultation, exchange of information, and collaborative work. The choice of this approach can also be seen as a way of managing tensions between two superpowers who understand that they have no choice but to create mechanisms for dialogue in order to avoid escalation leading to dangerous conflict with international ramifications.

The Swords of Iron War changed the Israeli outlook, if not in practice, at least in awareness. Throughout the war, China criticized Israel’s actions, while the United States, under President Biden, stood with Israel almost without reservation. This experience makes it evident that Israel must not change its pro-Western and pro-American leaning and that it needs to adopt a clear policy. It is essential to maintain economic and civilian cooperation with China as a significant trading partner, while continuing to strengthen its strategic relations with the United States. At the same time, it will be challenging to avoid China’s problematic attitude towards it, which is unlikely to change as long as the war in Gaza continues, despite tactical improvements in recent months (Ben Tsur, 2025). It is also important to remember that Israel and its war with Hamas were not top priorities for the powers, even if they provided fertile ground for mutual taunts. In fact, Israel and the war have hardly been discussed between the powers, perhaps due to an understanding that there is a deep division between them on this issue and little potential for cooperation, like the case of the Russia-Ukraine war.

The attitude of both powers to the Swords of Iron War clarified beyond any doubt that the rivalry between them is not only, or perhaps even mainly, driven by conflicts of interests, but by ideological differences, which have even been defined as a “battle of ideas.” While one side sees itself as the leader of the developing world and the champion of revolutionary national liberation movements, the other sees itself as the leader of the free world and defender of democracy. It remains to be seen whether the Chinese approach to managing relations between the powers, which the Biden administration apparently adopted, will also be practiced by the second Trump administration. Initial indications suggest that while President Biden has chosen moderation and the marginalization of disputes, President Trump prefers the opposite approach, which revolves around applying pressure through high trade tariffs and confrontation on issues of disagreement, alongside attempts to build a personal relationship with President Xi. It appears that Trump is less likely to confront China on non-economic, less significant matters. As evidence, his administration announced that it would review parts of the AUKUS Alliance (Reuters, 2025), established during the Biden administration, that are of particular concern to China.

Looking back on these four years, China can point to some success in showing the United States that it should take China’s views, interests, and red lines into account, and even adopt its approach to inter-power relations. Cutting off most of the channels of communication between them following Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan was a clear indication that China takes very seriously what it perceives as American, if not presidential, support for Taiwan’s independence. Perhaps even more importantly, the crisis China created enabled it to examine the US commitment to the existing arrangement and to maintain two-way communication to prevent escalation. The United States responded quickly and in a way that even China probably did not expect, by sending an airlift of senior officials eastwards to try to narrow the gap between the countries. These officials discussed subjects on which cooperation was possible with their Chinese counterparts, while avoiding areas of disagreement—illustrating their willingness to adopt the Chinese approach.

This approach proved to be effective, and ties between the powers gradually returned to normal. Military coordination was the last element to be restored, perhaps due to a conscious decision by China to keep the most important aspect of relations with the United States to the end, to see whether it would cross any of China’s red lines. Indeed, after the Pelosi incident, there were no more visits to Taiwan by senior members of the Biden administration, apart from a visit about 18 months later by a delegation of Congress Members (American Institute in Taiwan, 2024), which was also criticized by the Chinese side (Tang, 2024a).

The fact that this approach was adopted and worked is, first and foremost, evidence of the Biden administration’s willingness to accept the Chinese way of working, and of its openness to different methods, based on its understanding that relations between the powers and the avoidance of escalation are more important than insistence on direct talks on areas of deep division. Moreover, it is possible that both governments understood that discussions of matters where there are strong disagreements, such as the war between Russia and Ukraine and China’s support for Russia’s war effort, not only do not help to resolve the dispute but also create further dangerous tensions between China and the US. This understanding is important because it reflects a kind of acceptance of the world order in which China is a rising power and the United States cannot always impose its wishes on it; it is better to ignore matters that could lead to military escalation and focus on areas where cooperation is possible.

Bibliography

AFP (2021, June 14). China accuses G7 of ‘manipulation’ after criticism over Xinjiang and Hong Kong. The Guardian. https://tinyurl.com/3z5245y9

American Institute in Taiwan (2024, February 22). US congressional delegation visits Taiwan. https://tinyurl.com/msbxdbwh

BBC News (2021a, March 19). US and China trade angry words at high-level Alaska talks. https://tinyurl.com/yc83p6rw

BBC News (2021b, September 17). AUKUS: China denounces US-UK-Australia pact as irresponsible. https://tinyurl.com/3afpe4ua

Ben Tsur, R. (2025, August 6). Biased Neutrality: China’s rhetoric in the arenas of escalation in the Middle East. Overview, Institute for National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/s7zcy4bb

Bermingham, F. (2025, July 4). Exclusive | China tells EU it does not want to see Russia lose its war in Ukraine: sources. South China Morning Post. https://tinyurl.com/4m9dm6t5.

Clark, J., & DOD News (2024, April 25). U.S.-led Ukraine coalition to meet amid renewed momentum. U.S. Department of War. https://tinyurl.com/fzzdu6hk

CNA (2021, March 20). After fiery start, US conclude ‘tough’ talks with China. https://tinyurl.com/9azj2uey

Collinson, S. (2021, June 14). Biden pushes China threat at G7 and NATO, but European leaders tread carefully. CNN. https://tinyurl.com/43e3wufw

Consulate General of the People’s Republic of China in New York (2023, October 16). Wang Yi talks with Blinken over phone on Palestinian-Israeli conflict, China-US ties. https://tinyurl.com/22bacd6b

Delaney, R. (2023, May 11). Top US and China envoys meet in Vienna, the highest in-person engagement since Xi and Biden in November. South China Morning Post. https://tinyurl.com/ykdu2jnv.

Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States (2021, November 16). President Xi Jinping had a virtual meeting with US President Joe Biden. https://tinyurl.com/5n8ujsj5

Everington, K. (2021, September 24). US house passes bill inviting Taiwan to take part in 2022 RIMPAC. Taiwan News. https://tinyurl.com/2bdac9hy

Evron, Y. (2015). China’s diplomatic initiatives in the Middle East: The quest for a great-power role in the region. International Relations, 31(2), 125-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117815619664

Herb, J., & Cheung, E. (2022, August 2). US house speaker Nancy Pelosi lands in Taiwan amid threats of Chinese retaliation. CNN. https://tinyurl.com/3p3524nk

Jakes, L., & Myers, S.L. (2021, March 19). Tense talks with China left U.S ‘cleareyed’ about Beijing’s intentions, officials say. The New York Times. https://tinyurl.com/bdzk59yy

Kewalramani, M. (2025, April 21). CFAU President Wang Fan analyses China’s Neighbourhood Diplomacy Approach. Tracking People’s Daily. https://tinyurl.com/37c66m4r

Khaliq, R. (2024, September 7). China blames US for failure on ceasefire as war on Gaza nears one year. AA. https://tinyurl.com/rr3ahvym

Kube, C., & Lee, C.E. (2024, January 25). U.S. intelligence officials determined the Chinese spy balloon used a U.S. internet provider to communicate. NBC News. https://tinyurl.com/2j2vrmce

Lederer, E.M. (2023, December 9). US vetoes UN resolution backed by many nations demanding humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza. AP. https://tinyurl.com/bdfdtvsz

Magid, J. (2023, October 25). Russia, China block US Security Council resolution backing Israeli right to self defense. The Times of Israel. https://tinyurl.com/hvnnmmxd

Magnier, M., & Wang, O. (2023, February 19). China-US relations: At Munich meeting, Antony Blinken tells Wang Yi balloon incident ‘must never again occur’. South China Morning Post. https://tinyurl.com/y7ef433s

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of The People’s Republic of China (2022, March 19). President Xi Jinping has a video call with US President Joe Biden. https://tinyurl.com/5n6c2ca4

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2025, May 12). Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian’s regular press conference on May 12, 2025. https://tinyurl.com/aep8bbmz

Ng, T. (2022, February 22). Beijing berates US for ‘trying to include Taiwan in strategy to contain China’. South China Morning Post. https://tinyurl.com/2nycfnba

Pamuk, H. (2021, November 24). U.S. invites Taiwan to its democracy summit; China angered. Reuters. https://tinyurl.com/yyuae8yk

Pamuk, H., Ali, I. Martina, M. (2023, February 4). Blinken postpones China trip over ‘unacceptable’ Chinese spy balloon. Reuters. https://tinyurl.com/43h82hub

Permanent Mission of China to the United Nations (2023, October 25). Explanation of vote by Ambassador Zhang Jun on the UN Security Council draft resolution regarding the Palestinian-Israeli situation. https://tinyurl.com/2jn6utrr

Plummer, R. (2022, August 4). Taiwan braces as China drills follow Pelosi visit. BBC. https://tinyurl.com/4nztue7x

Reuters (2022, February 4). Moscow-Beijing partnership has ‘no limits’. https://tinyurl.com/3ctv5uzn

Reuters (2025, June 12). Trump administration reviewing Biden-era submarine pact with Australia, UK. CNN. https://tinyurl.com/5fymsanr

Shalal, A., M. Martina, & R. Woo (2022, March 18). After Biden-Xi call, U.S. warns China it could face sanctions if it backs Russia in Ukraine. Reuters. https://tinyurl.com/mw52re3j

Sevastopulo, D. (2024, August 25). The inside story of the secret backchannel between the US and China. Financial Times. https://tinyurl.com/3pjv845x

Sun, D., & Zoubir, Y. (2017). China’s participation in conflict resolution in the Middle East and North Africa: A case of quasi-mediation diplomacy? Journal of Contemporary China, 27(110), 224-243. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1389019

Tang, D. (2024a, February 22). China demands the US stop any official contact with Taiwan following a congressional visit. AP. https://tinyurl.com/54u8auht

Tang, D. (2024b, October 17). US imposes sanctions on Chinese companies accused of helping make Russian attack drones. AP. https://tinyurl.com/mu47mhmv

Tatlow, K.T. (2025, February 10). Exclusive - Chinese spy balloon was packed with American tech. Newsweek. https://tinyurl.com/42zzxuc5

The White House (2022a, March 18). Readout of President Joseph R. Biden Jr. call with President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China. https://tinyurl.com/3xtchba8

The White House (2022b, November 14). Readout of President Joe Biden’s Meeting with President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China. https://tinyurl.com/mw2533tk

U.S. Department of State (n.d.). Conflict resolution. https://tinyurl.com/39rm677r

U.S. Department of State. (2023, October 14). Secretary Blinken’s call with People’s Republic of China (PRC) Director of the Office of the Foreign Affairs Commission and Foreign Minister Wang Yi. https://tinyurl.com/42m2x8rc

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (2024, September 9). Readout of commander U.S. Indo-Pacific command call with PLA Southern Theater Commander. https://tinyurl.com/fxh4f5rf

Van Staden, C. (2023, December 20). China doesn’t join US led Red Sea force. China in the Global South Project. https://tinyurl.com/55kr5y2e

Wong, T., & Wang, F. (2023, February 17). How has China reacted to the balloon saga? BBC. https://tinyurl.com/5ckcjdjh

WSJ (2025, January 15). “It was the most tense moment”: U.S. ambassador to China exit interview [Video]. https://tinyurl.com/dnna8mvk

Xinhua (2023, October 15). Wang Yi talks with Blinken over phone on Palestinian-Israeli conflict, China-U.S. ties. https://tinyurl.com/2ucs4jx9

Xinhua (2024a, September 10). Chinese, U.S. theater commanders hold video talk. https://tinyurl.com/msk7ujjp

Xinhua (2024b, November 17). Xi says U.S. must not cross four red lines. https://tinyurl.com/bdhu562y

Xuanzun, L., & Yuandan, G. (2021, October 14). China, Russia hold joint naval drill in Sea of Japan, display ‘higher level of trust, capability.’ Global Times. https://tinyurl.com/5n9xk7wd

Xuanzun, L., & Yuandan, G. (2023, July 26). China, Russia to hold third joint naval patrol in West, North Pacific. Global Times. https://tinyurl.com/ypwehb2x

Yao, K. (2021, September 22). China’s high-tech push seeks to reassert global factory dominance. Reuters. https://tinyurl.com/4udavzdv

Yousif, B.N. (2023, February 10). President Biden says balloon was not a major security breach. BBC. https://tinyurl.com/bdf3xt5b