Strategic Assessment

The Arctic region has become a focal point of competition between leading global powers—the EU and USA against China and Russia. This paper will review the interactions of these great powers in relation to climate change, economics, and security in the Arctic, and argue that the countries’ priorities in the Arctic are wildly different, with each actor placing a different emphasis on what it considers to be the most important interest.

Keywords: Arctic, High North, USA, EU, Russia, China, Global Warming, Militarization

Introduction

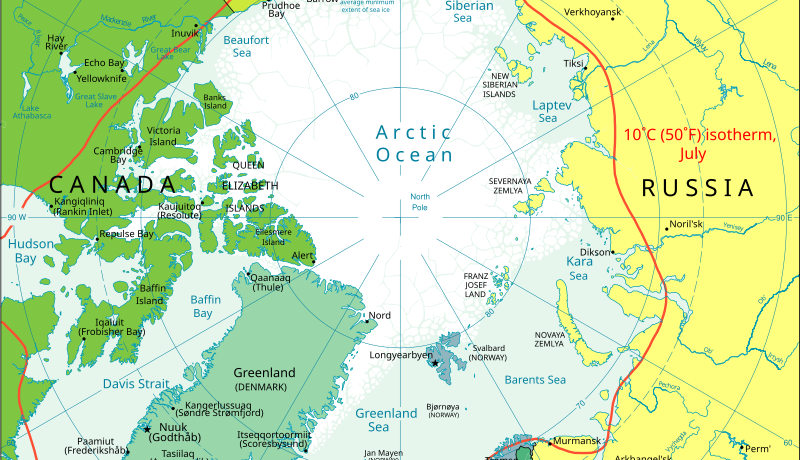

The Arctic is a remote region at the top of the world, defined as north of 66° North latitude. Despite its cold and isolated nature, the Arctic is home to approximately four million people, ten percent of whom are Indigenous (Arctic Council, n.d.-a). The region encompasses eight countries with territory north of the Arctic Circle: the United States, Canada, Greenland/Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia (Arctic Council, n.d.-b). Of these eight, five—the United States, Canada, Greenland/Denmark, Norway, and Russia— are considered Arctic littoral states, meaning they have direct coastlines along the Arctic Ocean (Degeorges, 2013). Iceland, despite being an island nation with its northernmost island above the Arctic Circle, is not classified as an Arctic littoral state because the sea to its north is the Greenland Sea, which is part of the Atlantic Ocean.

Source: CIA World Factbook

The Arctic is rich in natural resources, including rare earth elements, fish stocks, and hydrocarbons. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the region holds approximately 13% of the world’ s undiscovered oil and 30% of its undiscovered natural gas (eia, 2012). These resources are unevenly distributed; for instance, the majority of undiscovered hydrocarbon reserves are situated in Russian territory (Balashova and Gromova, 2017). Russia stands as the dominant Arctic power, possessing the largest share of land, population, coastline, natural resources, and military presence in the region (Paul and Swistek, 2022).

The Arctic, once a key theater of Cold War strategic competition, is again becoming a site of great power rivalry. During the Cold War, the region was seen as a potential corridor for nuclear attacks, as the shortest route for intercontinental ballistic missiles between the United States and the Soviet Union crossed the Arctic (Teeple, 2021). After the Cold War, the region experienced a period of relative calm under the informal arrangement of “High North, Low Tensions” (Ikonen, 2015), with the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy founded in 1991, which became the Arctic Council in 1996, whose charter forbids it from dealing with Arctic or other security issues. However, a new era of strategic competition is emerging, driven by the increasing interest of China—which calls itself a “near-Arctic state”—and Russia’s militarization of the region, alongside the strategic recalibration by the U.S., NATO, and Arctic allies such as Canada the EU. On top of that, those tensions have been turbocharged by the Ukraine War (Pechko, 2025). While military experts largely agree that the Arctic is unlikely to be the starting point for a great power war, there is growing consensus that any broader conflict involving major powers could quickly extend into the region, given its proximity to key players (Boulègue et al., 2024). As such, maintaining readiness in the Arctic while managing the risks posed by climate change is essential for all actors involved.

For many years, Arctic states adhered to the principle of “High North, Low Tensions,” a norm exemplified by the cooperative efforts of the Arctic Council (Taub and Pellegrin, 2024). The latter is an intergovernmental forum composed of the eight Arctic states, six Indigenous peoples’ organizations (the Aleut International Association, Arctic Athabaskan Council, Gwich'in Council International, Inuit Circumpolar Council, Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North, and the Saami Council), and numerous observers, including both states and international organizations with interests in the Arctic (Arctic Council, n.d.-b). Among the observers, two are particularly relevant to this paper: China, which is a permanent observer, and the European Union, which is a de facto observer. Despite being a consensus-based and non-binding forum, the Arctic Council has achieved notable success, including three legally binding agreements on Coast Guard coordination, oil spill cleanups, and scientific cooperation (Arctic Council, n.d.). The Council’s working groups also address a broad range of Arctic issues, excluding military security (Arctic Council, n.d.).

However, in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the work of the Arctic Council was suspended. At the time, Russia held the rotating chairmanship, and the other Arctic states—collectively referred to as the “like-minded” Arctic countries or A7—made it clear that they could not continue cooperation with Russia under the circumstances (Congressional Research Service, 2024). In 2024, the Council resumed limited activity, with working groups meeting remotely (Arctic Council, 2024). The Council has remained partially suspended, although the chairmanship, which rotates every two years, has since passed from Russia to Norway and is now held by Denmark/Greenland (Edvardsen, 2025).

Climate change, security, and economic opportunities are the main features of the Arctic’ s geopolitics. These elements are interlinked with each other. For example, climate change makes many economic opportunities in the Arctic possible. This is because many of the economic resources in the Arctic have been made accessible by the retreat of the ice that made accessing these resources—whether above or below the sea —possible. Economics interacts with security as well. Given that many of the resources could become targets in the event of war, or provoke geopolitical crises or intrigue, many countries are increasing their military assets in the Arctic to protect these resources. This is especially the case with Russia. However, climate change and security have also been intertwined in the Arctic. This has been demonstrated by the thawing permafrost which has ruined infrastructure throughout the Arctic.

This paper will review and compare the interests of China, the EU, Russia, and the USA regarding climate change, security, and economics and argues that their priorities regarding the Arctic are wildly different, with each actor placing a different emphasis on what it considers to be the most important interest.

Climate Change

Climate change is an urgent and accelerating challenge in the Arctic, which is warming nearly four times faster than the global average (Rantanen et al., 2022). This rapid warming is causing a dramatic reduction in sea ice (WWF Arctic, 2025), exposing the region to increased economic activity, such as expanded use of the Northern Sea Route and access to previously unreachable hydrocarbon reserves. However, these developments come with serious environmental and public health consequences. The thawing of permafrost not only releases vast quantities of greenhouse gases but may also, along with the melting glaciers, unleash ancient pathogens to which modern humans have no immunity (Wolfson, 2025) Moreover, Arctic Indigenous communities—already among the most vulnerable populations—face existential threats to their way of life, cultural continuity, and food security. Despite these risks, some states perceive climate change in the Arctic not as a crisis to be mitigated, but as an opportunity to exploit emerging economic and strategic advantages.

The divergence among these four powers’ Arctic climate strategies is stark. The EU promotes a cautious, mitigation-oriented approach grounded in science and multilateralism. China and Russia prioritize strategic advantage and economic gain, often at the expense of climate responsibility. The United States, once a climate leader, now appears to be stepping back from meaningful Arctic engagement under the Trump 2.0 administration. This imbalance weakens the potential for coordinated global climate action at a time when the Arctic is warming nearly four times faster than the rest of the planet. Without alignment among these major powers, the region faces the risk of accelerated environmental degradation, ecosystem collapse, and irreversible global climate tipping points.

Russia

Russia is one of the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitters, a position reinforced by its intensive exploitation of Arctic fossil fuels (Tracy, 2023). These activities not only add directly to global emissions but also accelerate warming in one of the most fragile regions on earth. Ironically, while Russia drives Arctic warming, it is also increasingly vulnerable to its effects. Melting permafrost undermines infrastructure, Arctic communities face food insecurity and health risks, and ecosystems are disrupted (Polovtseva, 2020). Yet Moscow tends to view climate change less as a crisis than as an opportunity, seeing new possibilities for resource extraction as sea ice recedes (Hardy, 2025). This pragmatic, if short-sighted, stance is reinforced by Russia’s reliance on hydrocarbon revenues and its growing isolation following the invasion of Ukraine. While officials speak of sustainability, such rhetoric is largely symbolic, masking a lack of real mitigation (Sönmez, 2025).

The Russian Arctic’s contributions to climate change are varied and severe. Melting permafrost releases methane, a greenhouse gas many times more potent than carbon dioxide, creating a dangerous feedback loop (Polovtseva, 2020). Black carbon from shipping along the Northern Sea Route also exacerbates warming. Produced by burning heavy fuels, it not only heats the atmosphere but also settles on snow and ice, darkening surfaces and hastening melt (McVeigh, 2022). Meanwhile, drilling, mining, and combustion of Arctic fossil fuels release vast additional emissions (Tracy, 2023).

The effects are already visible. Much regional infrastructure was built on the assumption of permanently frozen ground. As permafrost thaws, pipelines, roads, and buildings warp or collapse, creating economic and safety risks (Polovtseva, 2020; Shemetov, 2021). Indigenous peoples such as the Nenets face cultural and economic challenges: reindeer herding is threatened by ice crusts that block access to lichen, disrupting both livelihoods and traditions ( Stammler, 2023). Industrial accidents also reveal how warming interacts with human activity. In Norilsk, one of the world’s most polluted cities, thawing permafrost caused a fuel tank to rupture in 2020, spilling tens of thousands of tons of diesel into rivers. While climate change did not directly cause the leak, it created the conditions for disaster and complicated cleanup (Polovtseva, 2020).

Russia’s economic model reinforces this trajectory. The retreat of Arctic ice is seen in Moscow as a logistical advantage, opening new mining and drilling sites and reducing transport costs (Bradley, 2023). Longer ice-free shipping seasons make it easier to move resources via the Northern Sea Route, linking Arctic hubs more directly to Asian markets. This has allowed Russia to expand extraction while bypassing the need for expensive inland infrastructure. After the invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin’s reliance on Arctic revenues only deepened. Oil, gas, and mineral sales now provide a financial lifeline to support military operations, even as they worsen global warming (Fenton and Kolyandr, 2025; Savytskyi, 2024).

Some Russian elites even portray climate change as beneficial. Warmer temperatures might, in their view, expand Siberian farmland or reduce heating costs. President Vladimir Putin has dismissed environmental activism and downplayed climate risks, reflecting a broader indifference—and at times opportunism—within the political leadership (BBC, 2024). This mindset helps explain Russia’s lack of meaningful climate commitments. Its most recent nationally determined contribution under the Paris Agreement avoided real emissions cuts, leaning instead on forests as carbon sinks (Savytskyi, 2024). Yet experts note that fires, logging, and degradation undermine the forests’ capacity to offset emissions (Koralova, 2024).

In practice, Russia’s Arctic remains both a driver and a victim of climate change. Its extractive strategy delivers short-term gains but deepens long-term risks for its people, ecosystems, and infrastructure. With domestic incentives for mitigation weak and geopolitical isolation high, Russia shows little willingness to alter course. Its policies remain largely symbolic, combining ambitious rhetoric with limited action, while the region it dominates continues to warm at more than twice the global average.

EU

The European Union approaches climate change in the Arctic through three major lenses: scientific research, the green transition, and international cooperation. These priorities align with the EU’s broader climate agenda and foreign policy goals, but they have come under strain since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Although cooperation with Russian institutions has been suspended, EU climate researchers acknowledge that progress on Arctic climate monitoring is difficult without Russian participation, given the sheer scale of Russian territory in the region.

The EU has long prioritized climate science as a foundation for effective Arctic policy. Projects like EU-PolarNet, supported under the Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe frameworks, are designed to coordinate European polar research and strengthen the continent’ s scientific capabilities in the Arctic (EU-PolarNet, 2024). Through other initiatives, such as the Copernicus Climate Change Service and the Copernicus Marine Service, the EU also gathers critical satellite and observational data related to Arctic oceanography, sea ice, and permafrost changes (Copernicus, 2024). Targeted programs like Nunataryuk, which focus on permafrost thaw and its effects on northern communities, further exemplify the EU’s comprehensive scientific approach to Arctic climate risks. Shared infrastructure, including the Arctic Research Icebreaker Consortium (ARICE), helps EU member states pool resources like icebreaker vessels to support pan-European polar research (ARICE, n.d.). This scientific collaboration is essential for understanding the Arctic’s role in the global climate system.

The EU’s second major concern is the Arctic’s role in the green transition. As part of the European Green Deal, the EU has called for leaving Arctic hydrocarbon reserves untouched, framing Arctic fossil fuel development as incompatible with Europe’s climate goals (Rankin, 2021). However, as demonstrated by EU oil company activity, this ideal is not upheld. At the same time, the Arctic holds strategic value for the green transition in other ways. The region may supply critical raw materials—such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements—needed for renewable energy technologies and battery production. Moreover, the EU sees potential in Arctic offshore wind energy, which could become a key component of its broader strategy to decarbonize energy systems (Wilson, 2020). These dual imperatives—preserving Arctic ecosystems while responsibly sourcing key resources—create tensions in EU policy, especially as external powers like Russia and China continue to develop Arctic hydrocarbons.

International cooperation is the third pillar of the EU’s Arctic climate engagement. Before 2022, the EU promoted multilateral and bilateral scientific cooperation with key Arctic players including Russia, the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. This approach enabled European researchers to gain access to datasets and fieldwork opportunities across the circumpolar Arctic. However, the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine fundamentally disrupted these patterns. Following the invasion, the EU adopted a policy of suspending institutional collaboration with Russian scientific bodies. Researchers from Russian universities and institutes were cut off from EU-funded programs, and many were unable to communicate with foreign colleagues due to fear of repression (Matthews, 2023). The threat of politically motivated arrests—sometimes referred to as “hostage diplomacy”—further discouraged travel and collaboration. In parallel, a growing number of EU researchers became uncomfortable with the prospect of working alongside Russian scientists who either supported the war or were compelled to voice support under pressure. One senior EU researcher summed up the mood by saying that few EU researchers want to work with a Russian scientist who says, “Let me tell you why we had to invade Ukraine”—a scenario that epitomized the irreconcilable political and ethical tensions at play (Wilson Center, 2024).

Despite the political rupture, EU climate scientists are acutely aware that Russian cooperation is essential to comprehensive Arctic monitoring. Over half of the Arctic’ s landmass and coastline lies within Russia, and Russian territory hosts a significant number of key climate observation sites. Since the war began, European researchers have been operating with data from less than half of their usual Arctic data points, leaving critical gaps in monitoring climate feedback loops like permafrost thaw, methane emissions, and sea ice retreat (Wilson Center, 2024). As a result, there is growing frustration in Europe’s scientific community about the limitations of the current research environment. Many researchers acknowledge the need for eventual re-engagement with Russian science. Nevertheless, strong support for Ukraine and concern over legitimizing Russian aggression continue to constrain such collaboration. While individual partnerships between EU and Russian scientists are technically permitted, they remain rare and politically sensitive, with little institutional support or protection.

It is worth pointing out that there are some differences between EU-Arctic states and the rest of the EU when it comes to climate change. EU Arctic states seem to be less interested in drilling for fossil fuels in the Arctic than states like France and Italy. Additionally, EU Arctic States view the Arctic as a resource base more than the European Commission does, as the Commission ‘s primary attitude to the Arctic is as an area that should be treated as a nature reserve. As a result, there are some differences when it comes to how the EU vs. the EU Arctic states view global warming in the Arctic.

USA

U.S. climate change policy has become increasingly erratic and polarized, particularly when comparing the period before the second Trump administration to the current era, whose policy seems to deny climate change, hinder it’s scientific investigation and exacerbate the climate crisis. Prior to President Trump’s return to office in 2025, federal agencies such as NASA were central players in Arctic climate research. These agencies led efforts to map coastal erosion, monitor the rising sea-level in Alaska, track permafrost thaw, and measure greenhouse gas emissions such as methane from wildfires. Academic institutions and think tanks also played an active role in studying both the science of Arctic climate change and its social and policy implications. For example, the Polar Institute at the Wilson Center examined governance challenges and national climate policy (The White House, 2023; Wilson Center, n.d.).

Following Trump’s reelection, however, the US government adopted a stance of climate science denial, resulting in sweeping cuts to climate-related research and institutions. The administration’s FY2026 budget proposed $163 billion in spending reductions, largely targeting nondefense discretionary spending. These cuts significantly affected agencies involved in environmental research, such as NASA, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Washington Post Staff, 2025). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a key agency for Arctic and oceanic climate data, faced a proposed budget cut of nearly $1.7 billion, reducing its total funding to $4.5 billion (KCCI, 2025). This erosion of support for evidence-based policymaking has further marginalized climate science within the federal government. The closing of the U.S. Arctic Research Consortium was another example of how the USA is decimating climate science. Even institutions like the Wilson Center, previously regarded as politically neutral, were targeted for defunding by Elon Musk’s DOGE (Hansen, 2025).

The United States’ retreat from global climate leadership has provided a strategic opening for China. As the world’s leading producer of solar panels and a major investor in renewable energy infrastructure, China has tried to positioned itself as a credible actor in global climate governance. By contrast, the U.S. has been seen as regressing into climate denial. This stark divergence has made it easier for Beijing to present itself as a responsible power—especially among countries most affected by global warming. Arctic nations grappling with melting permafrost and coastal erosion, Pacific Island countries facing existential threats from rising sea levels, and African states already experiencing climate-driven desertification and food insecurity may be increasingly receptive to China’s messaging. In this context, the Trump administration’s climate posture not only undermines US credibility in international environmental diplomacy but also accelerates the erosion of American influence in strategic regions vulnerable to climate change.

It seems that the second Trump administration chose not only to reverse the Biden administration’s policies but also to go further. While the first Trump administration did not see significant cuts to the budgets of government agencies conducting climate change research, his second term saw deeper reductions. It is worth noting that many senior U.S. Arctic scientists—who had been in the federal service under the Bush administration and encouraged younger scientists who joined under Obama to remain during Trump’s first term—ultimately retired because of the administration’s hostile stance toward science. The first Trump administration’s anti-climate science approach also extended into foreign policy. For example, during at least one Arctic Council meeting, then–Secretary of State Mike Pompeo sought to exclude any reference to climate change from the joint communiqué.

China

China has a few key concerns regarding climate change in the Arctic. The Chinese are particularly interested in three overlapping issues: science, access to resources, and governance. These priorities are seen by Beijing as central to its recognition as an Arctic stakeholder. They also provide China with added leverage in its strategic rivalry with the United States and the West more broadly, helping to enhance China’s legitimacy in international forums and supporting its long-term positioning in great power competition.

Chinese interest in Arctic climate science is rooted in self-interest. Coastal cities like Tianjin and Shanghai face existential threats from a rise in sea-level if current emissions trends continue unchecked. In recent years, China has also suffered from intensified typhoons and other climate-related disasters. These domestic vulnerabilities drive China’s expanding investment in polar research. Through scientific expeditions aboard research vessels like the Xuelongs and Ji Di, and operations at its Arctic research base in Ny-Ålesund, on the Norweigan island of Svalbard, China has conducted studies on ice thickness, ocean salinity, and climate change patterns in the Arctic (Khanna, 2025; Wei et. al., 2019). This research serves two purposes: understanding climate impacts at home and projecting scientific credibility abroad. By contributing to global climate knowledge, China bolsters its image as a responsible actor. However, it’s also worth noting that Chinese science has been accused of having a dual purpose of both civilian use and military applications.

The second major climate-related concern for China is the increased access to Arctic natural resources. As the ice sheet continues to thin due to global warming, the region is becoming more accessible for economic exploitation. China has taken a strong interest in energy and mineral extraction possibilities in the High North. A notable example is the Yamal LNG project in Russia’s Arctic, in which Chinese companies are major investors. The project’s ability to ship liquefied natural gas to China via the Northern Sea Route—an increasingly viable path thanks to climate change—demonstrates the strategic economic opportunities that warming has enabled (Puranen and Kopra, 2023; Sakib, 2022). Additionally, China has conducted research vessel voyages around mineral-rich offshore areas along the Alaska coast, which might indicate an interest in seabed mining off of Alaska in international waters (Lajeunesse and Lalonde, 2023).

The third issue tied to climate change is Arctic governance. China has long argued that global warming has turned the Arctic into a region of international concern, with implications far beyond the eight Arctic states. As a result, it claims that non-Arctic states should have a say in how the region is managed (State Council, 2018). Beijing promotes the idea that the Arctic is part of the global commons, and that climate change necessitates inclusive governance (Doshi, Dale-Huang and Zhang, 2021). This position directly challenges the current Arctic Council structure, which limits decision-making to member states. China’s call for a more open Arctic governance regime is not just rhetorical—it reflects a long-term effort to shift the rules in its favor, aligning with broader Chinese approaches to multilateralism and institutional influence.

These concerns—scientific, economic, and institutional—are tightly interwoven in China’s campaign to be recognized as an Arctic stakeholder. China has consistently cited its scientific contributions to justify its status as a permanent observer in the Arctic Council, a position it achieved in 2013. At the same time, its 90 billion dollars of investment in the Arctic signal a growing economic footprint, further reinforcing its stakeholder claims. And by promoting the idea that climate change makes the Arctic relevant to all, China aims to rally support from other non-Arctic states and expand its influence in regional governance.

Global warming in the Arctic also intersects with China’s broader rivalry with the West, particularly the United States. China has sought to position itself as a leader in climate governance at a time when U.S. leadership on the issue has been inconsistent—most notably during the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. Some small island nations have looked favorably upon China’s climate posture, in part because of its rhetorical commitment to addressing climate change (Rasheed, 2025). In this context, climate leadership becomes another front in the wider struggle for international legitimacy and geopolitical influence.

Comparison

The approaches of China, the European Union (EU), the United States, and Russia to climate change in the Arctic reveal deep divisions in global environmental governance. While all four are major emitters of greenhouse gases, their policies toward a warming Arctic differ significantly in ambition, intent, and consequence. These differences have far-reaching implications—not only for the Arctic itself, but for the broader global climate system.

The European Union has emerged as the most climate-forward actor among the four powers. The EU’s Arctic strategy reflects a precautionary and science-based approach that prioritizes environmental protection, sustainable development, and the rights of Indigenous communities. Brussels has set ambitious climate goals aimed at decarbonization and explicitly supports international efforts to limit Arctic exploitation. It has also taken a strong stance on reducing black carbon emissions and banning oil exploration in vulnerable Arctic areas. Despite internal inconsistencies and occasional greenwashing within member states, the EU consistently promotes climate-sensitive Arctic policies in multilateral forums, attempting to align economic interests with ecological responsibility.

China, by contrast, views Arctic warming through a largely opportunistic lens. As melting ice opens up previously inaccessible sea routes and resources, Beijing has moved to secure a foothold in the region under the label of a “near-Arctic state.” Chinese climate rhetoric often emphasizes participation in global governance, and the country has joined Arctic Council activities as an observer. However, China’s engagement is largely driven by strategic and economic calculations rather than a commitment to climate mitigation. While promoting itself as a responsible stakeholder, China benefits from maintaining lower environmental standards at home, allowing its industries to compete globally while exploiting Arctic infrastructure and shipping opportunities. Climate change is seen less as a crisis and more as a pathway to national advantage.

The United States’ position has shifted dramatically over recent years. Under previous administrations, the U.S. was a global leader in Arctic climate science and adaptation. Agencies such as NASA, NOAA, and the EPA conducted pioneering research on Arctic warming, sea ice decline, and community displacement. Support programs were established for Alaska Native populations facing erosion, thawing permafrost, and habitat loss. However, the return of the Trump administration has reversed much of this progress. Climate change has been downplayed or denied, scientific research has been defunded, and environmental regulations rolled back. This retreat from Arctic climate engagement weakens US leadership globally and removes a key voice for science-based policymaking in the region, leaving a policy vacuum at a critical moment.

Russia stands apart as the most extractive and least environmentally constrained of the four powers. The Kremlin views Arctic warming as a net benefit, providing greater access to oil, gas, and mineral reserves as well as opening the Northern Sea Route for commercial shipping. Rather than addressing the climate risks tied to permafrost melt or black carbon emissions, Russia has accelerated Arctic development—often with minimal environmental oversight. The Arctic has become a key economic lifeline for Moscow, particularly in financing the war in Ukraine through energy exports. Russia’s official climate discourse includes vague commitments to sustainability, but in practice, environmental mitigation remains a low priority. Exploitation continues even in the face of infrastructure collapse and growing harm to Indigenous communities.

Economic Interests

Economic interests in the Arctic are increasingly shaped by the opportunities created by climate change. As global warming accelerates the melting of sea ice, previously inaccessible resources—such as hydrocarbons and mineral deposits—are becoming more attainable. In response, China, the European Union, and the United States each approach the emerging Arctic economy with distinct strategies and priorities. Although the Arctic remains a marginally profitable region at present, the economic potential is gradually improving as environmental barriers diminish. While the region may not yet be ready for full-scale economic exploitation, it is steadily moving closer to becoming a viable frontier for investment and development. The EU remains committed to environmentally conscious development and scientific cooperation. China and Russia pursue extractive, infrastructure-heavy models that seek to leverage Arctic change for national gain. The United States, once more aligned with the EU, is now repositioning itself as a resource competitor.

Russia

Russia’s economic strategy in the Arctic centers on three interlinked priorities: resource extraction, infrastructure development, and the Northern Sea Route (NSR) (Rumer, Sokolsky, & Stronski, 2021). The region holds immense reserves of hydrocarbons, minerals, and other resources that underpin Russia’s energy exports and industrial capacity. The Yamal Peninsula has become the cornerstone of Arctic gas production, home to Yamal LNG and Arctic LNG-2. Other Arctic areas host major oil fields, further strengthening Russia’s export position (Kontorovich, 2015). Beyond hydrocarbons, the region is rich in nickel—mined at Norilsk, which is one of the world’s largest producers—, critical for steel and batteries (Geological Survey of Norway, 2016). Murmansk contains deposits of rare earth elements vital for electronics and defense technologies (Kalashnikov et. al., 2023). Russia also ranks among the top global producers of gem-quality diamonds (Bennett, 2021), while lithium extraction led by Rosatom signals an ambition to enter green supply chains (Reuters, 2025). Coal is also present, though declining global demand limits its importance (Staalesen, 2019).

Exploiting these resources requires significant infrastructure, but much of the Arctic remains inaccessible (U.S. Congress, 2015). Harsh climate, permafrost, and remoteness drive up costs of construction and maintenance, while road, rail, and port facilities remain sparse. Historically, Russia partnered with Western firms to overcome these challenges. Before the 2014 annexation of Crimea, companies like ExxonMobil, Shell, and Total supplied capital and advanced offshore drilling and LNG technology, enabling projects such as Arctic LNG-2 to proceed with greater technical sophistication and safety standards (Closson, 2017). These partnerships highlighted Russia’s reliance on foreign expertise for Arctic development.

The rupture with the West after 2014 forced Russia to pivot. Sanctions targeted energy and financial sectors, leading Western firms to withdraw. In their place, China emerged as Moscow’s key partner. State-backed Chinese companies and banks provided critical funding, logistical support, and technology for Arctic projects. This partnership allowed Russia to sustain development momentum, but it also created new tensions. Russia is cautious about granting Beijing too much leverage in a region central to its sovereignty and security. While Chinese investment is welcomed, Moscow balances cooperation with limits on Chinese influence to preserve strategic autonomy (Rao and Gruenig, 2024).

The Northern Sea Route forms the third pillar of Russia’s Arctic economic vision. Stretching from the Bering Strait to the Barents Sea, the NSR lies entirely within Russia’s exclusive economic zone (Ustymenko, 2025). By cutting shipping times between Europe and Asia by up to 40 percent compared to the Suez Canal, it offers significant commercial potential. For the Kremlin, the NSR is not only a trade artery but also a potent symbol of sovereignty. Russia envisions it as a key channel for energy exports to Asia, strengthening its role as a dominant Arctic power.

Yet the NSR remains underdeveloped and operationally difficult. Ice conditions require year-round icebreaker escorts, and the lack of robust ports, refueling hubs, and search-and-rescue facilities hampers reliable shipping (Todorov, 2023). Existing ports such as Pevek and Tiksi are tiny, isolated, and poorly connected to national transport networks. Pevek has fewer than 5,000 residents, limited air service, and minimal road access; Tiksi faces similar constraints (Wikivoyage, n.d.-a, n.d.-b). These shortcomings restrict the NSR’s capacity to scale into a global commercial corridor.

China has shown strong interest in supporting NSR development, offering investment and Arctic-capable shipping technology (Marine Insight, 2025). Such cooperation could accelerate progress, but Russia remains protective. While Beijing is invited to contribute, Moscow resists ceding any measure of control, making clear that sovereignty over the NSR is non-negotiable (Reeves, 2025). The Arctic is not only an economic resource but a core element of Russian strategic identity. Putin has welcomed Chinese participation but has also set boundaries, preferring targeted cooperation over joint ownership.

In sum, Russia’s Arctic economic ambitions are vast but constrained. The region’s hydrocarbons, minerals, and shipping routes promise wealth and influence, yet they require infrastructure, technology, and international partnerships that sanctions and geopolitical isolation make difficult to secure. China provides critical support but also introduces strategic dilemmas, as Moscow seeks to balance dependence with autonomy. Meanwhile, environmental challenges, high costs, and underdeveloped infrastructure complicate long-term plans. Russia’s ability to turn Arctic potential into reality will depend on how well it manages these obstacles while guarding sovereignty over one of its most sensitive regions.

EU

The European Union's (EU) economic interests in the Arctic are primarily driven by its commitment to addressing climate change and bolstering innovation. This focus is evident in initiatives such as the European Green Deal, Horizon 2020, and its successor Horizon Europe, which fund Arctic-related research and innovation projects aimed at promoting sustainable development and environmental protection. The European Green Deal is the European Union's (EU) flagship initiative aimed at achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, with a significant focus on transforming energy systems and reducing greenhouse gas emissions (European Council, n.d.). Notably, the EU has invested approximately €200 million in Arctic research through these programs (German Arctic Office, 2022).Teh European Union’s (EU) economic interests in the Arctic are influenced by its commitment to environmental sustainability, particularly through initiatives like the European Green Deal. However, these interactions often intersect with the oil sector, highlighting a complex relationship between environmental goals and economic interests. While the EU aims to reduce carbon emissions and promote renewable energy, certain projects under the Green Deal have faced challenges due to economic constraints, environmental concerns, and national priorities.

To meet these goals under the Green New Deal, the EU is investing in renewable energy sources, including wind and hydroelectric power, and securing critical raw materials essential for the green transition. The Arctic region presents vast potential for renewable energy and critical mineral resources. Sweden, for instance, has identified significant deposits of rare earth elements in the Kiruna area, which are vital for manufacturing electric vehicles and wind turbines (LKAB, 2023). Similarly, Norway is advancing offshore wind energy projects and exploring seabed mineral resources to support the EU’s renewable energy objectives (Videmšek, 2024; Urdal, 2024).

In terms of funding, the European Union (EU) has utilized its Horizon 2020 program and its successor, Horizon Europe, to support sustainable development in the Arctic. Between 2014 and 2020, Horizon 2020 invested approximately €200 million in Arctic-related research, encompassing areas such as environmental studies, digitization, healthcare, and innovative technologies (German Arctic Office, 2022). Horizon Europe, the EU’s current research and innovation program, continues to provide substantial funding (200 million Euros) to strengthen the EU’s involvement in the Arctic, aligning with objectives like climate change adaptation and sustainable development (European Commission, n.d.).

Despite the EU’s commitment to environmental protection in its 2021 Arctic policy, which advocates for leaving Arctic hydrocarbon resources untapped, individual member states have not always aligned with this guidance, particularly when operating in non-EU parts of the Arctic. This divergence underscores the complexity of implementing cohesive environmental policies across different jurisdictions, especially when national economic interests and energy security concerns are at stake. Major economies like France and Italy have expanded their presence in the Arctic through investments in non-EU territories. For instance, France’s energy company TotalEnergies held a 10% stake in Russia’s Arctic LNG 2 project. However, following Russia ’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and subsequent international pressure, TotalEnergies announced its withdrawal from the project, resulting in a $4.1 billion financial write-off. (Humpert, 2022).

Italy’s Eni has been active in Arctic oil exploration and production. In Norway, Eni operates through its subsidiary Vår Energi, focusing on hydrocarbon exploration and production (Eni, 2018). In Alaska, Eni began production at the Nikaitchuq field in 2011, marking its first operated Arctic project (Eni, 2011). However, in 2024, Eni agreed to sell its Nikaitchuq and Oooguruk upstream offshore assets in Alaska to U.S.-based Hilcorp as part of its strategy to rebalance its upstream portfolio (Eni, 2024). Additionally, Italian engineering firm Saipem was involved in constructing infrastructure for Russia's Arctic LNG 2 project (Dempsey, 2019).

USA

American policies toward the Arctic economy can largely be divided into two phases: the pre-Trump 2.0 era and the Trump 2.0 era. The 2022 National Strategy for the Arctic Region (NSAR) emphasized sustainable development as a cornerstone of U.S. Arctic policy. The federal government supported initiatives focusing on the digital economy, green energy, and the blue economy, alongside related loan programs. The 2022 strategy acknowledged the rapid warming of the Arctic and advocated for the region’s newly accessible resources to be developed sustainably. Infrastructure development played a key role in this vision, exemplified by the planned construction of a deepwater port in Nome, Alaska, to support economic activity and resilience (The White House, 2022, 2025a).

Another central component of the pre-Trump Arctic policy was a focus on Alaska Native communities. These Indigenous groups, among the earliest peoples in North America, have historically experienced significantly lower standards of living compared to non-Native Alaskans. Federal efforts sought to improve conditions for these communities by relocating villages rendered uninhabitable by climate change. For instance, the village of Newtok faced severe challenges due to erosion and melting permafrost, leading to a relocation effort to Mertarvik (Bowmer and Thiessen, 2024). Additionally, the 2022 National Strategy for the Arctic Region (NSAR) emphasized the importance of supporting Alaska Native communities in adapting to climate change impacts (The White House, 2023). Additionally, transferring federal assets, such as the only tribal college in Alaska located in Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow), to Native ownership has also been a way to promote sustainable development among the Alaska Native peoples.

Before the escalation of the war in Ukraine, American oil companies were actively involved in Russian Arctic energy projects. ExxonMobil, for instance, had significant investments in the Sakhalin-I project, a major oil and gas development in Russia’s Far East. However, following Russia’ s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, ExxonMobil announced its withdrawal from the project (ExxonMobil, 2022). This move marked a significant shift in US involvement in Russian Arctic energy ventures. The Arctic LNG 2 project, led by Russia’s Novatek, relied heavily on international investment and Western technology, with US companies like Baker Hughes contributing essential technology, such as turbines. However, after the imposition of US sanctions in November 2023, foreign shareholders suspended their participation, leading to significant challenges for the project’s financing and implementation (Gardus and Savytskyi, 2024).

Under President Donald Trump’s second term, US Arctic economic policy has undergone a significant transformation, marked by a pronounced shift toward fossil fuel development and a departure from previous climate-focused initiatives. In January 2025, the Trump administration rescinded prior protections and authorized oil and gas drilling across 1.56 million acres of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), reversing a moratorium implemented during the Biden administration (The White House, 2025b). This decision aligns with a broader agenda to expand domestic energy production, including plans to offer oil and gas leases on 82% of the 23 million-acre National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (Spring, 2025). Concurrently, the administration has revitalized efforts to construct a massive liquefied natural gas (LNG) pipeline intended to transport gas from Alaska’s North Slope to southern ports for export, primarily targeting Asian markets. The proposed 800-mile pipeline, estimated to cost $44 billion, has garnered interest from countries like Japan and South Korea (Gardner, 2025).

China

Chinese investment in the Arctic has been heavily concentrated in extractive industries, particularly in Russia. The most significant Chinese stakes are in Russia’s Arctic natural gas projects, notably Novatek’s Yamal LNG in 2014 and Arctic LNG 2 in 2019. Chinese entities hold a combined 29.9% stake in Yamal LNG and 20% in Arctic LNG 2, with investments from China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), and the Silk Road Fund (Rao and Gruenig, 2024). Yamal LNG primarily supplies gas to Europe, with limited exports to China. In contrast, Arctic LNG 2 has seen deeper Chinese involvement. Following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Western companies withdrew from the project, creating a vacuum that Chinese firms, including Wison Engineering and several shipping companies, stepped in to fill—despite U.S. sanctions (Humpert, 2025a). China has also invested in other Russian mining ventures, such as the 2024 Polar Lithium project. This joint venture between Russia's Rosatom and Nornickel, with technical backing from China’s MCC International, aims to develop the Kolmozerskoye lithium deposit in Murmansk (Staalesen , 2024). However, the project faces obstacles, including 2025 US sanctions and potential Chinese withdrawal, which could impact Russia’s goal of becoming a significant player in the global lithium market (Staalesen, 2024). Outside of Russia, Chinese investment success in the Arctic has been more limited and has often encountered resistance.

In Canada, Chinese firm Shandong Gold Mining has attempted to acquire stakes in a mine containing gold .However, in 2020 the deal faced a national security review and outright rejection from Canadian authorities due to strategic concerns (Daly and Lewis, 2020). In Alaska, from 2009, China’s state-owned China Investment Corporation has held a stake in the Red Dog Mine, although this project has committed environmental violations (Pezard et. al, 2022; Hagen, 2024). Additionally, China has expressed interest in Alaska’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) sector, including a 2017 framework agreement with Alaska Gasline Development Corporation (AGDC), though the project was cancelled by a later governor (Downing, 2025). In Greenland, Chinese companies such as Shenghe Resources and China National Nuclear Corporation have pursued investments in rare earth and uranium-rich sites, including the Kvanefjeld project. However, in 2021, local and Danish political resistance, especially over uranium extraction, has led to major setbacks or bans (Hall, 2021; Reuters, 2021). As a result, by value and scale, Russia remains China’s primary Arctic investment destination, particularly in the energy and mining sectors, due to both resource availability and the two countries' growing strategic alignment in the face of Western sanctions (The Belfer Center, 2024).

China’s trade with Arctic countries remains modest in scale and largely follows a pattern of importing raw materials and exporting manufactured goods. China imports natural gas from Russia, particularly from the Yamal LNG project, where Chinese companies hold substantial stakes (Humpert, 2025b). From Norway, China imports large quantities of seafood, especially salmon, making it one of Norway’s key seafood markets (Godfrey, 2024). In turn, China supplies manufactured goods to Arctic states—most notably to Russia, where consumer goods exports have surged following the exit of Western firms due to sanctions related to the Ukraine war (The Moscow Times, 2022). This pattern underscores China’s traditional global trade role even within the relatively narrow Arctic trade network.

China has also undertaken infrastructure projects in the Arctic, notably under its Polar Silk Road framework, first articulated in 2017. This initiative envisions integrating Russia’s Northern Sea Route (NSR) with maritime routes extending from Norway through the North Sea to Northern Europe (Weisko, 2025). Most Chinese infrastructure investments have focused on the Russian-controlled segment of this route. These include stakes in the port of Arkhangelsk taken in 2025, and the construction of a rail link to Arkhangelsk in 2024, aimed at improving access to the Arctic through the Arctic Express No. 1 stopping in Arkhangelsk (Daly, 2024; Russia’s Pivot to Asia, 2025). China has also been involved in port infrastructure development along the NSR, such as proposed projects in Tiksi (Bischoff, 2023). In addition, in 2023, China’s New Shipping Line started sailing the Northern Sea Route, creating a direct shipping route between Shanghai and Europe via the NSR (Humpert, 2023). Chinese investment has been courted in northern Norway, including infrastructure such as a bridge built in 2017 and the port of Kirkenes (Bochove, 2020 News in English, 2017). Additionally, the Chinese-linked ship Istanbul Bridge just sailed the NSR on a liner route, which is a big step for the commercialization of the NSR.

Many Chinese investments in the Arctic have failed, often due to shifting economic conditions or national security concerns. Some failures stemmed from commodity price declines—for instance, during the 2010s, falling global iron and copper prices rendered several Chinese-backed mining projects in Greenland economically unviable (Jiang, 2021). However, a number of failures have resulted from national security apprehensions about Chinese involvement in strategic sectors and locations. In Canada during the year 2020, authorities blocked the acquisition of TMAC Resources’ Hope Bay gold mine by Chinese state-owned Shandong Gold, citing national security concerns (BLG, 2020). In Finland during 2021, a Chinese-backed plan to buy an airport near a military training area was rejected, partly due to strategic reasons (Nilsen, 2021). In 2013 Iceland, a controversial proposal by Chinese businessman Huang Nubo to develop a large golf resort on unsuitable terrain raised public and political alarm, ultimately leading to its rejection (Higgins, 2013). In 2018 Greenland, Chinese investors were blocked by the Danish government from purchasing the decommissioned Grønnedal naval base, previously used by the Danish navy. Denmark intervened to prevent the sale on national security grounds (Breum, 2018). Additionally, in 2019, Chinese construction firms were denied contracts for an airport renovation projects in Greenland after security concerns were raised by both Danish and American officials (Hinshaw and Page, 2019).

Comparison

The economic strategies of China, the European Union (EU), Russia, and the United States in the Arctic reveal competing visions for the region’s future. While the divergence among them is less immediately destabilizing than their differences on security matters, these varied approaches reflect deeper tensions around environmental governance, sustainable development, and economic power in a rapidly changing Arctic.

China’s Arctic economic strategy is centered on securing access to resources, expanding trade routes, and embedding the region into its broader Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) through the development of the Polar Silk Road. Beijing views the Arctic as a new frontier for economic integration, where it can extract critical raw materials, invest in energy infrastructure, and facilitate the northward flow of goods along newly navigable shipping lanes. The melting of Arctic sea ice has opened the door for these ambitions, allowing China to forge investment partnerships—most notably with Russia—to establish a long-term economic presence in the region. While China publicly emphasizes cooperation and peaceful development, its approach is largely extractive and strategically transactional, designed to advance Beijing’s global economic influence.

Russia’s economic orientation in the Arctic closely aligns with China’s, particularly in the wake of growing international isolation following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. With Western sanctions cutting off traditional avenues for investment and trade, Russia has doubled down on Arctic resource extraction as a cornerstone of its wartime economy. Energy exports from the Arctic—particularly liquefied natural gas (LNG) and oil—remain vital to funding the Russian state. Russia’s development of the Northern Sea Route also complements China’s Polar Silk Road, creating a shared interest in turning Arctic waterways into commercially viable alternatives to traditional global shipping routes. For Moscow, the Arctic is not only an economic asset but also a geopolitical tool for strengthening ties with non-Western powers and maintaining economic resilience in the face of sanctions.

In contrast, the European Union has articulated a vision for Arctic economic engagement rooted in environmental sustainability, innovation, and responsible governance. The EU’s flagship programs, including the European Green Deal, Horizon 2020, and Horizon Europe, support research and development that addresses climate challenges while promoting green growth. These initiatives encourage sustainable practices in Arctic development and seek to balance economic activity with long-term ecological protection. Brussels has consistently advocated for leaving Arctic fossil fuels untapped and prioritizing Indigenous rights and local community welfare. However, the EU’s internal cohesion is not absolute. Member states with Arctic territories, such as Denmark and Finland, may at times pursue national policies that emphasize resource development or industrial activity in ways that diverge from the EU’s broader environmental goals, creating a degree of strategic ambiguity within the bloc.

The United States has oscillated between different Arctic economic strategies, shaped largely by shifting domestic political leadership. Under previous administrations, the U.S. emphasized climate adaptation, scientific research, and sustainable economic development, with a focus on supporting Alaska Native communities affected by permafrost thaw and sea-level rise. The federal government also invested in renewable energy and Arctic resilience initiatives. However, the second Trump administration has marked a clear departure from this approach. U.S. Arctic policy now places increased emphasis on energy exploration, resource extraction, and strategic competition. There have even been signals of potential cooperation with Russia in Arctic energy ventures, highlighting a more opportunistic posture. This shift brings the US approach closer to that of China and Russia, prioritizing economic utility over environmental stewardship.

These diverging Arctic economic strategies underscore conflicting global priorities. While these economic differences may not provoke immediate conflict, they pose long-term risks to Arctic governance, environmental stability, and climate mitigation efforts. The absence of a shared vision for the Arctic’s future limits the potential for coordinated action in a region that is becoming increasingly central to global economic and environmental dynamics

Security

The security landscape of the Arctic is increasingly fragile. The region is effectively divided between the A7—comprising the like-minded Arctic states—and Russia. Among all Arctic actors, Russia stands out as the dominant military power. It possesses more icebreakers, military installations, Arctic coastline, and territory in the region than all other Arctic states combined (Gronholt-Pedersen and Fouche, 2022; Conley, Melino and Alterman, 2020). This imbalance underscores the need for the A7 to enhance their collective capabilities to deter and respond to a more assertive and militarized Russia. Meanwhile, China has been gradually positioning itself in the Arctic, largely by aligning with Russia to gain access. However, Moscow has been hesitant to fully integrate Beijing into Arctic affairs, limiting China’s involvement despite their growing strategic partnership. China’s support for Russia amid the war in Ukraine has further deepened suspicion among the A7, many of whom now view Beijing as a potential security threat in the Arctic. As a result, China’s Arctic ambitions remain heavily dependent on Russia’s willingness to grant it a foothold in the region. The USA seems to treat the Arctic as a theater for security competition. This has been demonstrated by the Biden Administration’s numerous policy papers put out by armed services. Trump’s push to acquire Greenland under the guise of national security concerns further shows that the Arctic remains important to the current administration. It seems like the EU’s Arctic security strategy is to keep Russia out; the Americans want to keep China out; the Russians want to preserve their security hegemony; while the Chinese simply want more security access.

Russia

Russia maintains a formidable military presence in the Arctic, combining new facilities with the modernization of Soviet-era sites. The Nagurskoye base on Franz Josef Land has been upgraded with advanced radar and anti-drone systems, while Rogachevo on Novaya Zemlya has been modernized to strengthen Russia’s strategic posture (Conley, Melino and Alterman, , 2020). These upgrades are part of a broader air and coastal defense network stretching 4,800 km from Franz Josef Land to the Chukchi Peninsula (Busch, 2017). Russia has also deployed S-400 missile systems along its Arctic coastline (Bermudez, Conley, and Melino, 2020a, 2020b), and Tu-95MS bombers based there have participated in long-range strikes on Ukraine (Nikolov, 2025).

The Northern Fleet, stationed in the Barents Sea, is Russia’s premier naval force and its most significant Arctic military asset. Equipped with ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) capable of striking the United States, the fleet benefits from defensive positioning in home waters. The fleet also operates Russia’s only aircraft carrier, the Admiral Kuznetsov, which launched strikes in Syria in 2016–17 but is now undergoing troubled repairs (Meduza, 2025); International Relations and Defence Committee, 2023). Despite setbacks, the fleet underscores the Arctic’s role in Russia’s broader power projection. Russia’s Arctic-trained ground forces add another dimension. The 200th and 80th Separate Arctic Motor Rifle Brigades, along with the 61st Guards Naval Infantry Brigade, all operate under the Northern Fleet’s Coastal Troops within the 14th Army Corps and are specifically trained and equipped for Arctic warfare; all have seen combat in Ukraine (Edvardsen, 2024).

Before its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s Arctic strategy had three priorities: protecting its second-strike nuclear deterrent in the Kola Bay region, projecting power into the North Atlantic via the GIUK gap, and safeguarding economic development through hydrocarbons, minerals, and new shipping lanes (Rumer, Sokolsky, & Stronski, 2021). The invasion shifted this calculus. The Arctic now functions as a secure rear base from which Russia can deploy high-value bombers and missile systems largely shielded from Ukrainian strikes. While Operation Spider Web demonstrated Ukraine’s ability to target facilities deep in Russia, Arctic bases remain relatively safe from persistent attack (Philp, 2025).

The war has also drawn heavily on Arctic manpower. The three Arctic brigades have been redeployed to Ukraine, suffering heavy losses (Humpert, 2023a). The 76th Guards Airborne Division, once stationed near Finland, also endured catastrophic casualties (UAWire, 2025). These losses have weakened Russia’s conventional ground presence in the Arctic, though analysts note its naval and air strength remains largely intact ( Gordon, 2023). Meanwhile, Indigenous peoples such as the Nenets and Yakuts have been disproportionately conscripted, bearing high per capita death rates that highlight deep inequalities and raise human rights concerns (Vyushkova, 2025).

Economically, the Arctic is central to Russia’s wartime resilience. Despite sweeping Western sanctions, resource revenues, especially oil and LNG, have sustained the economy and supported the war (Shevchenko, 2025; Darvas & Martins, 2022). A key factor is the rise of a “shadow fleet” of LNG tankers operating from Yamal and other Arctic facilities. These vessels conceal ownership through shell companies, sail under flags of convenience, and use deceptive practices like turning off transponders and covert ship-to-ship transfers (Katinas, 2024). Many are poorly maintained and underinsured, posing risks to the fragile Arctic environment. A major spill or collision would leave coastal states to bear the cleanup costs, as responsibility would be difficult to assign (Caprile & Leclerc, 2024).

In sum, the Arctic has become both a sanctuary and a lifeline for Russia. Militarily, it shields strategic assets and sustains long-range operations; economically, it finances the war through energy exports despite sanctions. Yet vulnerabilities are mounting: depleted ground forces, the exploitation of minority populations, and environmental risks from unregulated shipping threaten to undermine Russia’s Arctic strategy. The transformation of the region into a hub for both military and economic survival highlights its critical role in the Ukraine conflict, but also its fragility in the face of overextension and systemic strain.

EU

The European Union’s (EU) security interests in the Arctic are primarily shaped by concerns over Russia’s escalating militarization, the strategic role of NATO, and growing apprehensions about the reliability of the United States as a security partner. Even before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the EU had identified Russia as a principal security threat in the Arctic, driven by Moscow’s increasing military buildup in the region, signaling a shift from economic ambitions to military dominance in the region.

The EU addresses the Arctic military threat primarily through its participation in NATO, which remains the cornerstone of defense for nearly all EU countries (NATO, 2025a). The accession of Finland and Sweden—both EU members partially located in the Arctic—to NATO has significantly bolstered regional defense (Van Loon and Zandee, 2024). Finland contributes a large, well-trained army with deep expertise in Arctic warfare and strong artillery capabilities, while Sweden brings a highly capable air force (Black, Kleberg and Silfversten, 2024). Both countries were motivated to join NATO in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (BBC, 2022). Their membership has strengthened not only the EU defense posture but also NATO’s collective capabilities in the region (Moyer, 2024).

EU support for NATO operations in the Arctic also extends to joint military exercises. EU countries that are NATO members have actively participated in exercises such as Cold Response, which has seen Germany’s Sea Battalion conducting winter warfare training in Norway (Federal Foreign Office, 2024). French aircraft, naval vessels, and troops have also participated in NATO exercises above the Arctic Circle (Renaudin, 2024). Since Sweden and Finland joined NATO, their territories have been used for hosting exercises and as tripwire deployments (AFP, 2024; NATO, 2025b). Recently, for example, U.S. bombers flew over Finland in a demonstration of NATO air power, escorted by Finnish jets (Nilsen, 2024).

USA

Historically, the U.S. has relied on a layered network of northern defenses, including the Cold War-era Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line and its modern successor, the North Warning System, which is jointly operated with Canada. These systems serve to monitor potential incursions into North American airspace through the Arctic (Regehr, 2018). Close cooperation with Canada through NORAD remains a cornerstone of US defense posture in the region.

Under President Donald Trump’s second term, US security interests in the Arctic have remained largely consistent with that of previous administrations, with a continued focus on countering Russian and Chinese influence. Despite renewed questions about the United States’ commitment to NATO, particularly under Trump’s leadership, NATO officers stationed in the Arctic report that operational cooperation remains steady. For example, the U.S. continues to participate in Arctic-focused military exercises, such as Formidable Shield 2025, which involved over 2,500 troops from ten NATO countries and was designed to test integrated air and missile defense systems in the High North (Nilsen, 2025). Additionally, Trump has decided that America has security interests in the Arctic. The American near-Arctic has been in the news as part of the efforts to stop the war in Ukraine, where Putin and Russia met at the largest U.S. military base in Alaska in order to help negotiate an end to the Ukraine War.

Alaska continues to serve as a central hub for American Arctic strategy. The U.S. Army’s 11th Airborne Division, reactivated in 2022, focuses on Arctic operations and cold-weather readiness. Meanwhile, advanced air assets like the F-22 and F-35 remain stationed under Pacific Air Forces in Alaska. Plans to expand the Port of Nome into the United States’ first deepwater Arctic port—capable of supporting both military and commercial traffic—remain underway, although the project has faced delays and budget challenges (Humpert, 2024). There is also discussion about reopening the Adak Naval Base.

In recent years, Chinese activity in the Arctic has drawn increasing U.S. attention. While China is not a formal Arctic state, it has declared itself a “near-Arctic” power and has invested heavily in Arctic research, infrastructure, and shipping routes. In response, the U.S., Canada, and Finland signed the 2024 ICE Pact—a trilateral agreement to rapidly produce modern icebreakers using the assistance of Finnish experience, thereby addressing critical capability gaps in the U.S. and Canadian fleets (Homeland Security, 2024). This move aims to mitigate China’s growing capabilities in icebreaking capabilities, as China now possesses more than twice as many operational icebreakers as the U.S.

European reactions to Trump’s return have ranged from guarded optimism to outright skepticism; one Norwegian minister reportedly began a countdown to the end of Trump’s second term shortly after his inauguration (Thorsson, 2025). Nonetheless, Trump’s goal of weakening the Russia-China strategic axis may have the unintended effect of sustaining NATO’s relevance in Arctic strategy.

It is worth noting that under the second Trump administration, the United States has taken a markedly expansionist view of its Arctic-related interests, including the controversial idea of acquiring Greenland and even Canada. Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark, has drawn particular attention due to its strategic location and abundant natural resources. The justifications for the acquisition of Greenland are mostly security related, such as the presence of Russian and Chinese interests, with the economic reasoning often having some spillover to security reasons, such as rare earth elements and other critical raw materials.

The Trump administration has asserted that U.S. security interests would be advanced by bringing Greenland under American control. President Trump has repeatedly declined to rule out the use of force for such a move and has instructed the intelligence community to spy on Denmark and Greenland to assess various aspects of the process, such as on the ground support, to acquire Greenland. The Trump Administration, according to the New York Times decided to use an information operation to try to convince Greenland to either become part of US territory or form a Compact of Free Association with America, which is when a more powerful country gives a very weak country money in exchange for control over certain parts of the weaker countries policy, usually foreign and defense policy.

More provocatively, President Trump has previously also expressed a desire for Canada to become part of the United States, though the strategic rationale behind this claim remains unclear and largely rhetorical. It should also be known that Trump has a much more friendly relationship with the new Prime Minister of Canada, Mark Carney than he did with the former Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, who was the Prime Minister of Canada when Trump first voiced his designs on Canada. These assertions reflect a shift toward a more unilateral and aggressive posture in US Arctic policy under Trump 2.0.

China

China’s security interests in the Arctic are strongly tied with Russia. These interests are demonstrated through joint exercises, training programs, and defense equipment cooperation, which are primarily driven by China’s strategic interests in the region, which it identifies as a “Strategic New Frontier” (Van Loon and Zandee, 2024).

China and Russia have conducted joint military operations in the Arctic region, serving as interoperability training and geopolitical signaling. Notably, in July 2024, the two nations carried out their first joint strategic bomber patrol near Alaska, involving Chinese H-6K bombers and Russian Tu-95MS aircraft, escorted by Russian Su-30 and Su-35 fighters. This patrol marked the furthest north Chinese bombers have operated, entering the Alaska Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) but remaining in international airspace (Reuters, 2024). Russo-China joint patrols are designed to enhance the operational coordination between the Chinese and Russian air forces, allowing them to operate seamlessly in various scenarios. Additionally, they demonstrate the deepening strategic partnership between the two countries, signaling to Western powers that Russia and China have powerful friends in each other (Williams, Bingen and MacKenzie, 2024; Kendall-Taylor & Lokker,2023). The operations also provide China with valuable experience in long-range missions, including testing bomber routes from Russian airfields that could bring Alaska within striking distance. (Williams, Bingen and MacKenzie, 2024).

China and Russia have conducted joint coast guard exercises in the Arctic, which, while largely symbolic, provide practical training opportunities for Chinese forces operating north of the Arctic Circle. In October 2024, the Chinese Coast Guard participated in its first Arctic patrol alongside Russian counterparts, marking a significant expansion of China’s regional operational range. Beyond these exercises, China has supplied Russia with anti-drone systems deployed in Arctic regions, and dual-use and mostly non-lethal military equipment (Staalesen, 2025). These transfers have enabled Russia to sustain its war in Ukraine by compensating for the loss of Western military and technological inputs, particularly in explosives, drones, drone parts, semiconductors and advanced electronics.

China’s increased military interest in the Arctic is rooted in its strategic concept of “Strategic New Frontiers,” which encompasses areas such as the deep sea, polar regions, cyberspace, and outer space—domains perceived as rich in resources and lacking robust governance (Hybrid CoE, 2021). Additionally, China has used space related industries, such as the satellite station it rented from Sweden from 2016 until 2020 as a ground station for its BeiDou navigation system. This framework reflects China’s ambition to expand its influence and access to the global commons, aligning with its goal of becoming a leading global power.

Internally, Chinese military publications such as The Science of Military Strategy emphasize the importance of preparing the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) for potential conflicts in these frontier domains, including the Arctic (Doshi, Dale-Huang and Zhang, 2021). Additionally, Chinese commentators say that China, home to 20% of the global population, deserves 20% of the resources in the global commons. However, it is worth noting that the Arctic is generally agreed to be an area of spillover, not an area where the first shots will be fired. Externally, China’s 2018 Arctic White Paper articulates a commitment to peaceful cooperation and explicitly opposes the region’s militarization. The document outlines China’s intention to participate in Arctic affairs through scientific research, environmental protection, and sustainable development, positioning itself as a responsible regional stakeholder (State Council, 2018).

Additionally, Russia’s dependency on China for fueling its Ukraine war machine and filling the hole left by the exodus of Western consumer goods has made Russia vulnerable to Chinese demands to open up the Arctic to China. However, the Russians also do not trust the Chinese, and it could very well be that the Chinese are trying not to overstay their welcome in the Arctic, which would lead to greater resistance than the subtle hesitance that already exists. (Judah, Sonne & Troianovski, 2025)

Comparison

The security strategies of China, the European Union (EU), Russia, and the United States in the Arctic reveal a growing divergence in priorities, tactics, and visions for the region’ s future. While less immediately explosive than disputes over climate change, these differences pose serious long-term risks to Arctic stability and cooperation. Each power brings its own security agenda to the region, shaped by broader geopolitical trends and domestic political dynamics, resulting in a complex and increasingly contested Arctic landscape.

China’s approach to Arctic security is marked by subtle ambition and strategic positioning. While not an Arctic state, Beijing seeks to establish itself as a legitimate stakeholder through diplomatic engagement, scientific cooperation, and economic investment. Security, for China, is linked to securing access to Arctic sea lanes and resources, ensuring that no hostile bloc can deny its interests. Though China presents itself as a neutral actor focused on “win-win” cooperation, its growing alignment with Russia has clear security implications. By deepening economic ties with an increasingly isolated Moscow, China has gained access to infrastructure and influence in the region that would have been politically unthinkable a decade ago. However, this alignment is more opportunistic than ideological—Russia remains cautious of Chinese motives and reluctant to fully open the Arctic to Beijing’s influence, despite its current dependence on Chinese support.

Russia’s Arctic security posture is shaped by both strategic legacy and wartime necessity. The region hosts some of Russia’s most critical military assets, including second-strike nuclear capabilities based in the Kola Peninsula. Protecting these assets has long been a top priority, and the modernization of the Northern Fleet and Arctic airbases has continued even amid Russia’s war in Ukraine. Since 2022, the Kremlin has also used the Arctic as a relatively secure base from which to support operations in Ukraine, relocating high-value military systems away from areas vulnerable to Ukrainian strikes. Additionally, the redeployment of Arctic-based ground units to the Ukrainian front—where they have suffered heavy losses—has diminished Russia’s conventional military threat to NATO in the High North. Still, Russia views the Arctic as a vital domain for asserting sovereignty, ensuring strategic depth, and safeguarding the economic lifelines that help sustain its war effort.

The European Union, while not a military alliance, views Arctic security primarily through the lens of deterring Russian aggression and upholding regional stability. The EU has no unified military posture in the Arctic but relies heavily on NATO, and particularly on member states like France and the Nordic countries, to represent its security interests. Russian militarization and the potential fallout of a successful Russian campaign in Ukraine remain central concerns for European policymakers. At the same time, a growing unease about the reliability of the United States under the Trump 2.0 administration is reshaping EU thinking. Recent American rhetoric questioning the value of NATO and signaling potential disengagement has raised alarms across European capitals. As a result, the EU is increasingly exploring options for greater strategic autonomy in Arctic affairs, even as it continues to depend on transatlantic defense structures.

The United States, historically the bedrock of Arctic and transatlantic security, has adopted a more unpredictable and unilateral stance under the current administration. While U.S. Arctic Command and military presence in Alaska remain strong, recent policy shifts have undermined longstanding alliances and introduced uncertainty into regional security planning. Instead of serving as a stabilizing force, the U.S. now appears to prioritize short-term national interests and power projection in the Arctic. This includes renewed emphasis on Arctic energy exploitation and dominance in the region’s strategic chokepoints. These moves have strained relations with European allies and raised questions about the future of NATO cohesion in the High North.

Together, the diverging security interests of China, the EU, Russia, and the United States point to a more fragmented and contested Arctic future. All four actors are nuclear powers, and any miscalculation or escalation in the region carries catastrophic potential. The Arctic, once considered a zone of exceptional cooperation, now risks becoming a stage for great power rivalry. Without renewed diplomatic efforts and clear mechanisms for deconfliction, the Arctic’s strategic calm may give way to increasing militarization and confrontation in the years ahead.

Middle East Implications