Strategic Assessment

After each round of violent clashes between Israel and Hamas, the issue of rehabilitating the Gaza Strip and improving its economic situation is raised once again. The accepted working assumption is that given suitable political conditions, and in the framework of a political process based on an attempt to promote the realization of the two-state paradigm, in which the Gaza Strip and the West Bank are considered one political and territorial unit under the control of the Palestinian Authority, it will be possible to rehabilitate the Strip. But it appears that nobody has ever asked if the Gaza Strip can indeed be rehabilitated. In this paper I will try to clarify the meaning of “rehabilitation” in the context of the Gaza Strip, and with the aid of a matrix of variables, those that facilitate rehabilitation and those that disrupt it, examine a number of basic questions dealing with the actual feasibility of rehabilitating the Gaza Strip under existing conditions. Following that, with reference to my conclusion regarding the absence of sufficient conditions for a successful rehabilitation process, I will describe the characteristics of this state of affairs and its ramifications, and propose a number of possible options for dealing with the emerging situation in the absence of rehabilitation, with an emphasis on the importance of adopting logical guidelines which do not currently exist but which are here deemed to be essential for the success of such a process. The conclusion of this paper is that leaving Hamas in the Gaza Strip as a ruling entity and with their commitment to the preservation of the idea of armed resistance, are both strongly disruptive variables, and both are endogenous to the Palestinian system. Therefore, without neutralizing these two variables, or at least weakening them very considerably, it is hard to imagine that the rehabilitation process will succeed.

Key words: Gaza Strip, Hamas, the Palestinian Authority, the two-state solution, the Gaza Strip rehabilitation process.

Introduction: The Issue of Gaza Rehabilitation—an Ongoing Dilemma

The issue of rehabilitating the Gaza Strip has been on the agenda of political discussions and initiatives since June 2007,[1] when Hamas took control of the Strip, again after Operation Protective Edge in the summer of 2014, and with even greater intensity at present, in view of the scale of the destruction following the fighting between Israel and Hamas after October 7, 2023.

After each round of violent clashes between Israel and Hamas, the issue of rehabilitating the Gaza Strip and improving its economic situation is raised once again. In each round of fighting, buildings and infrastructure are damaged and the economic distress and humanitarian situation in Gaza become more severe. Due to the basic reality of the fact that the Strip is controlled by a terror organization that is committed to destroying Israel, with the added problems of overcrowding, poor infrastructure, and chronic lack of power and water, the issue is once again on the regional and global agenda, with greater intensity. In all discussions, neither Hamas nor the Palestinians are called to account for their actions, and the matter of reconstruction is simply accepted as an essential need, devoid of any responsibility on the part of those who inspired the destruction by cultivating their military strength and by building the capabilities and the conditions for attacking Israel, while ignoring their responsibility for the development of the Strip and Palestinian society. Over the years, and particularly since 2014, enormous resources have been invested in efforts to restore buildings and infrastructure, and construct new facilities such as the desalination plant, solar fields and water and energy infrastructure. From 2021 Israel participated in efforts to achieve economic improvements by employing Gazan residents in Israel, while a few years earlier it had already granted significant relief in the rules of importing and exporting goods into and out of the Strip.

Research institutes and international organizations have invested considerable efforts in drawing up plans to rehabilitate Gaza, although most were never implemented. The accepted working assumption was that given suitable political conditions, and in the framework of a political process based on an attempt to promote the realization of the two-state paradigm, in which the Gaza Strip and the West Bank are considered one political and territorial unit under the control of the Palestinian Authority, it would be possible to rehabilitate the Strip. But it appears that nobody ever asked if the Gaza Strip could indeed be rehabilitated.

This fundamental question takes on even more significance given the unique political and security conditions, where not only is it impossible to treat the Gaza Strip and the West Bank as a single political and territorial unit under the control of the Palestinian Authority, but there is also a situation of two rival Palestinian entities led by two competing leaderships, who have been unable to bridge the significant gaps between them since 2007. Even more seriously, since gaining power in the Strip in June 2007, Hamas has developed into a hostile, dangerous and violent semi-political entity, which has built a terrorist army and infrastructure with the aim of realizing its vision of destroying Israel. Hamas pursued its military aim systematically and thoroughly at the expense of the welfare of Gaza residents, choosing military strength over a functioning economy, civil society and national infrastructures whose purpose is to serve the citizens and implement responsible sovereignty. Over the years Hamas became part of the Iranian axis and shared Iran’s strategic vision of destroying Israel. Hamas was supported by Iran with money, armaments, training, technology and knowledge, and Iran was its full partner in the planning of the October 7, 2023 attack as the first stage in a long-term plan which it believed would lead to the erosion and eventual destruction of Israel by means of a continuous and intense war of attrition on multiple fronts. It is true that Hamas surprised Iran and Hezbollah by not sharing the timing of its attack with them, but following the seizure of thousands of documents in the course of the Iron Swords War, it became absolutely clear that Iran was not only aware of the plan but was a full partner in the planning and preparations.

The situation in the Gaza Strip after October 7 is the most difficult and complex that the region has experienced since 1948. The scale of the devastation is huge and the majority of the population is living in humanitarian shelters. Since its population comprises about two million people (based on data indicating the migration of about 200,000 people since the start of the war and the death of about 45,000, according to reports from the Palestinian Ministry of Health in the Strip), and in the absence of a functioning central government, infrastructures and natural resources, in addition to the lack of employment as well as limited options for migration, the issue of rehabilitation becomes far more complex, costly and prolonged, assuming that it is even possible.

To these challenging basic conditions must be added the security issue, with respect to Israel and the lessons it has learned about the region and the threats expected to emerge in the future. Apart from that, every move or effort to rebuild the Strip struggles under the heavy political shadow cast by the linkage of Gaza to the West Bank and the Palestinian Authority, and the ability of the PA to assume sovereignty in the Gaza Strip. The problem only gets worse when the international community and countries of the region, particularly those that are supposed to provide the driving force and the infrastructure for the reconstruction project, make their willingness to join in the task conditional upon an invitation from the Palestinian Authority and its active participation in the process. All this in a situation where the two-state paradigm that was so familiar to us until October 7 is no longer valid, in terms of public support on both sides for the idea and the degree of trust both populations place in this option, and it therefore requires updating in the spirit of the post-October 7 reality.

In addition, the rift between the Palestinian Authority and Hamas is still alive. All attempts at reconciliation since 2007 have failed. December 2024 witnessed the collapse of an apparent agreement between the two sides on the establishment of a technocratic committee to take over the running of the Gaza Strip and its post-war reconstruction. Consequently, in the absence of sufficient support and legitimacy for the two-state concept at this time on both the Palestinian and the Israeli sides, and since the PA is unable to assume the burden of implementing the idea by guaranteeing a stable and functioning Palestinian state, one that is ready to live alongside Israel as the nation state of the Jewish people, any determined attempt to steer the process of Gaza rehabilitation as part of a two-state solution under the leadership of the Palestinian Authority is doomed to failure.

In this paper I will try to clarify the very meaning of the concepts of “reconstruction of the Gaza Strip” or “a rehabilitated Gaza Strip,” with reference to a number of basic questions concerning the actual feasibility of rehabilitating the Strip under existing conditions, and to present logical guidelines for the process which do not currently exist but are here deemed to be essential for the success of the rehabilitation process. Following that, with reference to my conclusion regarding the absence of sufficient conditions for the rehabilitation process, I will describe the characteristics of this state of affairs and its ramifications, and propose a number of possible options for dealing with the emerging situation in the absence of rehabilitation.

What Does “Rehabilitation of the Gaza Strip” Mean, and Related Questions

The first question that must be asked is: What does the statement “rehabilitation of the Gaza Strip” or “rehabilitated Gaza” mean? And there are many other questions also waiting for answers:

- What are the factors that facilitate or encourage rehabilitation?

- What are the factors that inhibit or disrupt rehabilitation?

- What is the intensity of each factor (high or low)?

- Are each of the inhibiting or disruptive factors, the helpful or facilitating factors, endogenous or exogenous to the Palestinian system?

- Is it even possible to rehabilitate Gaza in the present conditions?

- If the Strip cannot be rehabilitated, what situation will emerge?

- What is the significance and what are the implications of this situation?

- How should these consequences be handled?

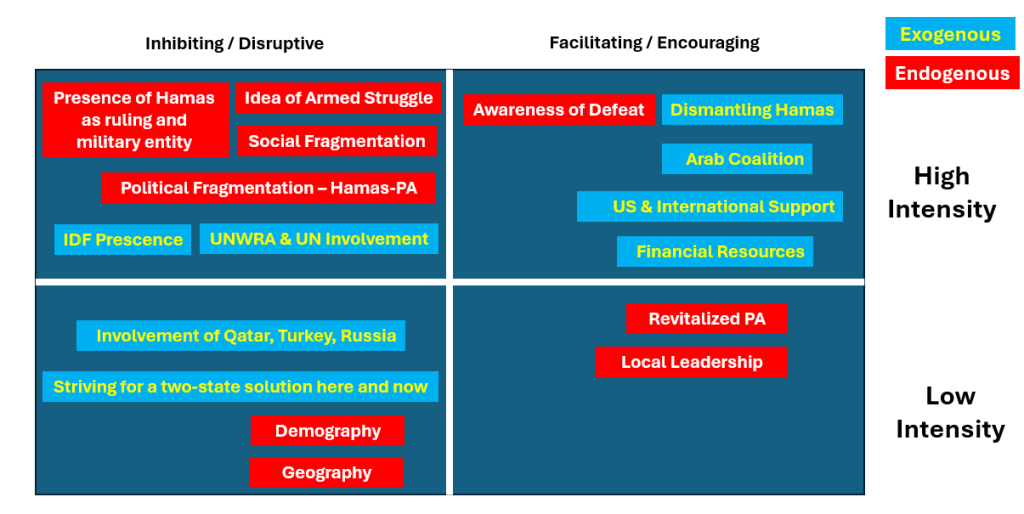

With reference to questions 1-4 a matrix of factors will be constructed (see below) to help with the analysis and assessment of the responses.

The Nature of Rehabilitation—What is the Meaning of “Rehabilitated Gaza”?

In the professional literature dealing with rehabilitation of failed states or disaster areas, the process is usually described as one of taking control of the territory, in order to create or rebuild the minimum physical infrastructures and social services that will serve as the spearhead to bring about social change through reforms in the political, economic, social and security spheres. The ultimate achievement is to enable self-rule (since the literature is essentially western, functioning self-rule usually implies liberal democratic governance), a functioning economy, security and social order which are not dependent on external financial aid or military support. It is important to stress that even when we rely on the accepted definitions in the literature, rehabilitation does not only refer to the physical aspect. It must also necessarily consider issues of society, law and order, security and the economy. The concept must therefore be tackled in a holistic manner, encompassing many dimensions.

In the case of the Gaza Strip, we need a relevant and agreed definition for the nature and purpose of the rehabilitation: The purpose must be to turn the Gaza Strip into a sustainable, functioning, responsible, non-subversive entity that strives for stability, with the potential and motivation to work towards economic development for the welfare of its residents.

Figure 1: Components and Measures of Rehabilitation

Source: Reuters – Extent of the destruction in the Shajaya district to the east of Gaza City after the Israeli forces announced the end of a two-week military campaign (July 11, 2024)

The elements of housing, infrastructure and even economy are expressions of the physical aspect of the rehabilitation process. Even if they are technically complex, and even if they require resources of time and money, such as the removal of huge amounts of building debris (some of which could perhaps be used to extend the land available for living in the Strip into the sea) and unexploded ordnance, as well as the development of the local economy, these problems are essentially solvable and do not constitute a disruptive element for any future reconstruction process. They are the easiest ones to implement, if a response can be found for the three less concrete but more important dimensions: security, society, and government/ institutions, which are the focus of this section.

The security aspect is an essential basic component without which rehabilitation is not possible. Ensuring a stable and secure environment requires the complete dismantling of both the political and the military wings of Hamas. Unless the organized political and military capabilities of Hamas are destroyed, there is not a single entity, either within the Gaza Strip or outside it, including the Palestinian Authority, that will agree to enter the Strip and develop an alternative government. And without an alternative to Hamas rule it will not be possible to rehabilitate political institutions or to enforce law and order in the territory. In the absence of these elements, there is no way of focusing on building the economy, infrastructures or the society, nor of creating a response to the housing shortage that has been exacerbated by the war.

Social rehabilitation—the collective psychological component: The discourse on rehabilitation focuses largely on infrastructure aspects, including housing, and on financial and institutional aspects, but there is little talk of social rehabilitation, which is a basic condition for the success of any process. Gaza lacked a developed, vital and functioning civil society even before the war, and certainly after it. The war has been a traumatic event that has severely damaged any cohesion that existed in Palestinian society in Gaza, which was weak in any case. Hamas arose from within Palestinian society and was supported by most of the population. Expressions of joy and ecstasy after the October 7 atrocities were seen in the streets of most towns in Gaza, and although support for Hamas and the murderous attack has declined, the movement is still widely popular, together with support for the October attack and the continuation of the armed struggle against Israel.

The psychological infrastructure of the Palestinian collective in Gaza, which rests on the ethos of refugee status, the right of return, continuation of the armed struggle against Israel, support for Hamas and the goal of destroying Israel, now has an additional layer of anger, offense and the desire for vengeance. This updated psychological basis feeds the idea of the struggle against Israel, and while it persists it will be impossible to recruit the Palestinian people for the long and exhausting process of historical rehabilitation in the spirit of the defined aim. The test of the concept of the ongoing struggle will be seen, inter alia, in the degree of commitment and priority given to the reconstruction of the refugee camps (for if the camps are reconstructed as such, their residents’ identity continues to be that of refugees waiting for Israel’s defeat, while the refugees’ integration into normative housing would indicate a forward-looking perspective not entirely focused on the struggle for Israel’s destruction).

The scale of the destruction offers a historical opportunity to completely eliminate the refugee camps in the framework of planning the rehabilitation of Gaza’s towns. The continuation of UNRWA’s activity and any significant involvement of the UN in the process will not be helpful in this context, but rather the opposite, and so it is important to ensure that these bodies are not part of the process. The complete demolition of the refugee camps and their replacement with new towns and villages is part of the necessary healing process for Palestinian society in Gaza and elsewhere. Such a move could be the catalyst to reshape the Palestinian ethos and undermine the idea of the struggle. If some of the resources for the reconstruction of Gaza are directed towards rebuilding the refugee camps, awareness of the struggle will be nurtured and become a disruptive and inhibiting factor in any process of rehabilitation.

The government-institutional component: Reconstruction of Gaza will require enormous resources, with estimates ranging from 80 to 100 billion dollars, but we must assume that the rich Gulf countries and the international community will be unwilling to sign up to efforts to raise the money in the absence of sufficient certainty regarding the chances of success, and above all the chances for long term stability. A high level of certainty can only be created on condition that Hamas is no longer a viable ruling or military entity and is replaced by a credible alternative. It is reasonable to assume that any countries that are willing to join the reconstruction effort, particularly the Arab countries, will make their assistance conditional on the active involvement of the Palestinian Authority in the process, and even on an official invitation from the PA. Moreover, any alternative government that is established must include a local Palestinian component, since the local population and leadership must be part of the reconstruction process. International experience shows that without the participation of the local population, any attempt to impose an external model of governance or rehabilitation is destined to fail.

On the other hand, the experience of the Oslo process years shows that full authority and responsibility for the rehabilitation process cannot be entirely entrusted to the Palestinians, the Palestinian Authority or any other Palestinian governing option. Since its establishment, the Palestinian Authority has shown no ability to function as a responsible and accountable state entity and its entrenchment as a failed, corrupt and in some cases terror-supporting organization means that it cannot be entrusted with the sole authority to manage the reconstruction process in the Gaza Strip. It is entirely beyond its ability to execute a task of this scale. Therefore, any Palestinian leadership included in the alternative to Hamas rule will need to establish a regional, international or combination task force, that will have responsibility for the reconstruction process by virtue of a defined and agreed mandate. Governing powers in the Gaza Strip should be transferred to Palestinian governance in a very gradual, responsible, and controlled manner, subject to progress in the reconstruction process and over a number of years.

To sum up, the main essential conditions for rehabilitation are): The wishes of the population and the leadership for rehabilitation, giving priority to rehabilitation over everything else, and the removal of the idea of struggle against Israel (including dismantling the refugee camps); a legitimate, committed, responsible and functioning leadership (which does not have to be popular); calm in terms of security; the potential for a developing civil society; social unity and mechanisms for effective healing of social fragmentation; resources; planning; assistance and control by external elements.

Disruptive and Facilitating Factors that Affect the Rehabilitation Process

The rehabilitation process will naturally be affected by a long list of variables or factors, some external (exogenous) to the Palestinian system and the Gaza Strip, and some internal (endogenous). Some of these variables promote the process or facilitate it, while others disrupt or even thwart the process, and the influence of each variable differs in intensity. For the purpose of presenting and analyzing the challenges, the variables are displayed by means of a matrix of external and internal factors that also shows the intensity of each one, in a binary division between strong and weak intensity. Obviously in reality the range of influences is broader, and between those at the strong end of the spectrum and those at the weak end, there are infinite values, but the matrix lays an analytical and conceptual foundation for planning the rehabilitation of Gaza, or at least increasing the chances of it happening.

Figure 2: Matrix of variables and their relative influence

The proposed matrix clearly shows that in the realm of high intensity facilitating factors, almost all of them are exogenous to the Palestinian system, while the majority of inhibiting or disruptive factors are endogenous. This means that special attention should be given to how the endogenous factors are handled before embarking on the rehabilitation process. Unless initial positive results can be produced, it is hard to predict success for the process in general, even given a very strong regional and international effort.

There is a further fundamental condition which is defined as external to the Palestinian system and of high intensity as a facilitator of rehabilitation, and this is the complete removal of Hamas as a governing and military entity. Only Israel can ensure this condition, since it is clear that there is not even one other player, including the PA itself, that is willing and able to assume this task. This means that the war in Gaza can only end after realization of the war aim defined by the Israeli government—dismantling Hamas. If the war ends before this is achieved, genuine rehabilitation will not be possible.

And yet this fundamental condition is not sufficient. A further essential condition is to shatter the Palestinian idea of struggle, or at least weaken it and transform it into a wish for rehabilitation, stability, security, and acceptance of the existence of Israel—giving up the armed struggle, the ethos of living as refugees and the right of return. These moves would mark the start of a vital deradicalization process, which will take years.

Complementary to this condition is the release from the historical and unrealistic adherence to the two-state paradigm in its familiar format of the last three decades. Stubbornly clinging to this paradigm and presenting it as a condition for the rehabilitation process will undermine and even prevent the process from starting. The paradigm in its historical format had never reached maturity, but the events of October 7 turned the Israeli public away from the concept and the collective national consciousness was deeply affected in a way that aroused strong opposition to the idea. A reflection of this picture can be found among the Palestinians in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and even more strongly in East Jerusalem.

The proposed matrix also contains factors defined as disruptive, whether of high intensity or low intensity, presented as negatives. The idea is that by their very presence these factors can disrupt the process, so to prevent their negative influence, it is important to ensure they are not part of the rehabilitation. For example, they include the UN and UNRWA, which over the years and more so since October 7, have become very problematical, due to their inbuilt bias against Israel, and above all because of their cooperation with Hamas terror and their historical contribution to perpetuating the conflict through methodical indoctrination of the ethos of refugee status and the right of return, alongside the ethos of the armed struggle. Qatar and Turkey, two typically Hamas-supporting countries, have worked and continue to work to maintain the status of Hamas as the most prominent and influential force in the Palestinian arena. Their participation in the rehabilitation process would interfere with the need to weaken the remnants of Hamas in Gaza and the start of the deradicalization process.

The revitalization of the Palestinian Authority by means of significant reforms (RPA) and the growth of local leadership in Gaza are two factors of great importance to the success of the process. While the intensity of their influence has been classified as low when compared to other facilitating factors, they are clearly crucial and necessary. Yet in the existing situation and the foreseeable future, it appears that the likelihood of reform of the PA and the growth of legitimate and functioning local leadership in the Gaza Strip is so low as to be negligible.

The Reality in the Absence of Rehabilitation

In the absence of rehabilitation and assuming the Israel will prefer not to conquer the Gaza Strip and impose military rule on it, even temporarily, in order to create suitable conditions for the establishment of an alternative to Hamas and the start of the process, it is possible to envisage two scenarios of differing probability.

IDF presence in the Strip: This is the more likely scenario, with IDF forces continuing to maintain a presence in the Strip, along the Netzarim corridor and along the Philadelphi corridor, and probably also along a newly breached corridor that separates Gaza City from the area to the north—the areas of Jabaliya, Beit Lahiya, Beit Hanoun and Al-Atatra (this scenario is a relevant scenario in the case of a crisis in the current ceasefire and hostage agreement—the prediction is that the agreement will be breached and not fulfilled in its entirety).

Without IDF presence in the Strip: In the second scenario there is no IDF presence in the area, except along its borders. The likelihood of this scenario is particularly low, assuming that a complete IDF withdrawal from the Gaza Strip would allow Hamas to rapidly reestablish itself and rebuild its military strength, renewing the security threat. Overcoming this threat would require a further military operation, or alternatively, routine forays by the IDF into Hamas power centers in the Strip, with the support of the civilian population.

Figure 3: Map of the Gaza Strip and areas of IDF activity

Source: The Data Desk, Institute of National Security Studies

Therefore we will focus on the first scenario, assuming that the most prominent features of the emerging situation will be as follows: A depopulated northern area (north of Gaza City); most of the population living in the Mawasi humanitarian and shelter area; Hamas as a partially functioning governing entity in the southern part of the Strip; humanitarian distress; protest against Hamas leading to subversion and power struggles; a descent into general chaos.

Consequences of a Situation Without Rehabilitation

The consequences of a failure to rehabilitate Gaza will be problematic and complex, both in relation to Israel and in relation to other players and regional stability. Without rehabilitation the humanitarian problems will become more severe, and in the absence of alternatives to humanitarian aid arriving from Egypt and distributed by international organizations, at some stage Israel will become responsible for the supply of humanitarian aid, and this will inevitably lead to friction in the face of terror attacks and relatively low intensity guerrilla fighting, with periodical outbreaks of higher intensity. Israel will face mounting international pressure and could encounter problems in its relations with Egypt and Jordan, and with the Abraham Accords countries. In addition and perhaps more seriously, the situation could damage relations with the American administration and other friends in the West. It would also reduce the likelihood of progress in the process of normalization with Saudi Arabia, and probably also have an adverse effect on the stability of the Palestinian Authority and the level of violent friction in the West Bank. Apart from all that, there is a very real possibility that a situation of ongoing violent friction will also affect the situation inside Israel, and could make the social and political rifts in Israel wider and deeper, as well as creating pressure on the economy due to the direct military costs of tackling the violence, the costs of reservists, the costs of transferring humanitarian aid, and the possible costs of setting up a military administration.

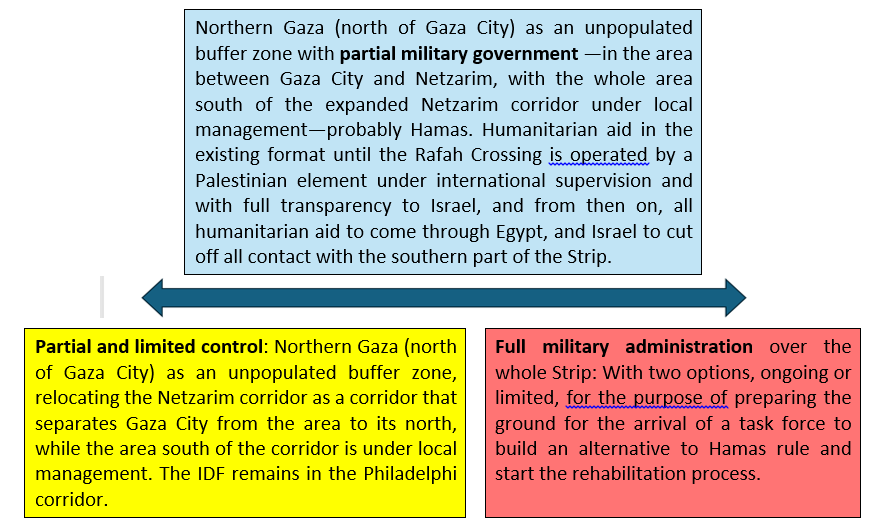

Options for Israel in the Absence of Rehabilitation

In the absence of rehabilitation, even in a gradual, lengthy process, and given the greater probability of an ongoing IDF presence in the Gaza Strip, because of the high risk embodied in the alternative of an IDF withdrawal to the border areas of the Strip, it is realistic to focus on the first scenario. In this case, there are three main options, where the common denominator is Israeli military control together with operation of the Palestinian side of the Rafah crossing by a non-Hamas Palestinian element, under close international supervision and with full transparency for the Israeli side. The difference between the options lies in the extent of military control and the presence or non-presence of the IDF in the Philadelphi corridor area.

Figure 4: Options in the absence of rehabilitation

All three options, with the emphasis on the full military government option, can be ongoing or limited in time, subject to circumstances and developments. It would be correct for Israel to aim for time-restricted military government and use this period to prepare the ground for the development of a civilian alternative to Hamas rule, as an essential condition for embarking on the comprehensive rehabilitation of the Gaza Strip. The military administration will define its objective as the complete eradication of Hamas as a sovereign entity in Gaza, will accept responsibility for the supply of humanitarian aid—even if not directly and through cooperation with aid organizations operating on the ground or private security companies—, and will deprive Hamas of vital oxygen and an effective platform from which to control the civilian population. Subject to gradual IDF withdrawal from the territory, the resulting conditions will make it possible to transfer Hamas-free, secure areas to the control of a technocratic Palestinian administration, accompanied by a regional-international task force until the process is complete. By that time there will be no Israeli military presence in the whole of the Gaza Strip, which will be run by the Palestinian administration with the support of the aforesaid task force, and rehabilitation will proceed without the presence of Hamas.

Yet Perhaps Rehabilitation is Possible After All? The Logical Guidelines to be Adopted

In view of the cost of dispensing with rehabilitation, and assuming there are initial signs of restraining the negative influence of endogenic factors on the Palestinian system, it is important to adopt a number of essential principles for any option chosen as the way forward to rehabilitation of Gaza.

The first principle is gradual progress. The extent of the destruction and the size of the challenge mean that the process of rehabilitation cannot start at once over the whole of the Gaza Strip. It will be necessary to work in a limited number of territorial cells defined as secure bubbles, and advance from bubble to bubble. The recommendation is to start in the north or in the south of the Strip—in the Rafah area next to the border—, since these areas are fairly sparsely populated and it will be possible to operate with relative freedom, speed and safety. The civilian population will return to the rebuilt areas in a controlled and gradual process to facilitate their orderly absorption.

The whole process of rehabilitation in each cell must start with the complete demolition of the refugee camps, and prevention of their reconstruction in that format. Rebuilding the refugee camps means adding fuel to the concept of the struggle, which will distract the Palestinian public, its leadership and all partners in the work from the efforts to achieve rehabilitation and the logic of the process. Therefore, as explained above, it is essential to ensure that UNRWA does not resume its role in Gaza, and that the UN plays no part in the process.

Operation of the Rafah crossing by a non-Hamas Palestinian entity, subject to the most stringent security requirements and complete transparency to Israel, is essential to the rehabilitation process. The Rafah crossing is where it is possible to transfer large quantities of raw materials and humanitarian aid quickly and efficiently. Putting a Palestinian element in charge of the reopened crossing also sends an important message to the Palestinians about the possibility of manifesting their responsibility and commitment to the process and to the future independence of the Gaza Strip.

Barring countries that support Hamas: Countries that support Hamas cannot be involved in the rehabilitation process, since their presence will increase the difficulties of promoting deradicalization or de-Hamasification in the Strip. Qatar and Turkey wish to preserve the status of Hamas as an influential element in the Palestinian arena, so it can be assumed that they will interfere with any deep and thorough reform of Gaza. Russia and China are also likely to disrupt the process, whether because of the support they have shown for Hamas over the years, including during the period since October 7, 2023, or for considerations of their position as revisionist powers that seek to undermine American hegemony in the existing world order. They could exploit their participation in the rehabilitation process as a lever to weaken American influence, which is essential as the spearhead of a regional coalition based on Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Jordan as the essential partners, together with other members of the international community, with the emphasis on some leading European countries such as Germany, France and Italy.

The involvement of the local population in the rehabilitation process, through legitimate leadership, is vital. The people must be part of the process and able to influence it. International experience of rebuilding regions of conflict and failing states demonstrates the importance of bringing in the local population rather than engineering solutions and imposing them from above. Involving the people helps to prevent reservations or opposition to reforms, provides sources of employment, encourages commitment, and above all creates a sense of community and ownership of the process and its outcomes.

Summary

During January 2025, ahead of the inauguration of President Trump on January 20, there was a stronger push to mediate between Israel and Hamas and to complete negotiations on the release of the hostages and an end to the war; an agreement was indeed signed and implementation began on January 19. The agreement also refers to the reconstruction of the Gaza Strip, which will begin in the third stage, and the working assumption of those involved in the negotiations appears to be that the Gaza Strip can indeed be rehabilitated under existing conditions and those that will be created the signing of the agreement.

The working assumption regarding the feasibility of rehabilitating the Strip under the familiar, existing conditions, with the emphasis on leaving Hamas in place as the governing entity, even if weakened, was not validated either before or during the negotiations. In fact, it appears that nobody has asked whether it is indeed possible to rehabilitate Gaza in these circumstances, or alternatively, what are the essential conditions for any successful rehabilitation.

My purpose in this paper was to tackle this question, under the assumption of a continuation of Hamas rule. In order to examine the question, I mapped out a range of variables that will affect any rehabilitation process. The variables were classified as either facilitating or inhibiting/ disrupting the process, and ranked by the intensity of their influence. They were also defined as either exogenous or endogenous to the Palestinian system. The variables were thus organized into a matrix, which serves as an analytical tool for examining the fundamental question of the feasibility of rehabilitating the Gaza Strip. The conclusion I reached is that the Gaza Strip—given the existing conditions and the continuation of Hamas rule, or its survival as a functioning organization, even in a weakened state compared to its position before October 7, 2025, with the psychology of the Palestinian collective based on the ethos of opposition and refugee status, which means the consciousness of struggle—cannot be rehabilitated.

The continued presence of Hamas in Gaza as a governing entity or even as an unofficial organization, and the consciousness of struggle, are defined as very strong disruptive variables, and both are endogenous to the Palestinian system. Without neutralizing these two factors, or at least significantly weakening them, it is hard to be hopeful that any rehabilitation process will succeed. It must therefore be assumed that even a successful conclusion to the negotiations, that have been conducted with extra vigor since the start of January 2025, which leaves these two variables in place, will not pave the way for a genuine process of rehabilitation in the Gaza Strip.

Notwithstanding the feasibility of President Trump’s vision regarding the reconstruction of the Gaza Strip after enabling the Palestinian residents to leave the Strip, his announcement is an important nod to the understanding that Gaza cannot be reconstructed under the current conditions and with the presence of Hamas. Trump’s declarations in this regard are no less than an earthquake and a paradigmatic shift that acknowledges the necessary and reasonable criteria for the reconstruction of Gaza.

____________________

* The term rehabilitation has been chosen as it contains the broader context of the challenge of rejuvenating Gaza, whereas “reconstruction” refers mainly to the physical dimension of the process. Due to the multi-dimensional nature of Gaza’s path to recovery, which includes crucial societal aspects, we prefer to use “rehabilitation” and not “reconstruction.”

[1] For example:

Udi Dekel & Anat Kurtz: Rehabilitation of the Gaza Strip – An urgent need

Planning the post-war reconstruction and recovery of Gaza