Publications

Special Publication, March 6, 2024

Senior Israeli officials continue to emphasize that Israel will keep fighting in the Gaza Strip “until victory,” but the question of what the public perceives as victory in this military campaign remains open. Using surveys conducted by the Institute for National Security Studies and analysis of media and public discourse in Israel, we claim that there is a disparity between the expectation of a clear image of victory and the actual possible end point. This disparity is also the product of vaguely defined aims, which have also changed during the war, fueling disputes and uncertainty about the necessary achievements. Moreover, the two declared goals of the war—securing the return of the hostages and dismantling Hamas—do not necessarily go hand in hand. It is also difficult to distinguish between actual victory and the public’s perception of one, which will render it more challenging to declare victory. To avoid the dangers of prolonged entanglement without a clear exit strategy and continued combat without a well-defined purpose, both of which could have serious implications for Israel’s military and society, it is imperative to have transparent and sincere leadership that clearly and honestly communicates the facts, alternatives, and choices made.

On December 24, during the 11th week of the war, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared: “We are intensifying the war in the Gaza Strip. The war has a price, a very heavy price in the lives of our heroic soldiers, and we are doing everything to safeguard the lives of our fighters. But there is one thing we won’t do—we won’t stop until we achieve victory.” His remarks came during long days of despondency, with daily reports of soldiers killed in battle and hostages declared dead, alongside the difficulty of showing significant, measurable gains in this war. The prime minister’s pledge that the war would not end until victory is achieved was directed at the Israeli public discourse, which has focused on the purpose of this phase of the fighting and the need to convene before the end of this intensive phase and, among some segments of the population, on concerns regarding the need to stop the fighting in exchange for the return of the hostages.

Even the transition to the third stage of the campaign several weeks later, despite the fact it was not declared, was accompanied by promises to the public that the war would continue and that fighting would not end until the aims were achieved. In his speech marking 100 days of the war, Netanyahu repeatedly emphasized: “We are continuing the war all the way until the end, until complete victory, until we achieve all of our objectives—eliminating Hamas, returning all of our hostages, and promising that Gaza will never be a threat to Israel.”

In this article, we claim that the slogan “until victory,” answering a public demand to defeat Hamas, in line with declarations made on the first day of the war, underscores a gap between the expected and clear image of victory and the feasible end point. This gap is partly due to the irrelevance of the concepts used, which characterize conflict with another state and not with a non-state adversary. Vaguely defined objectives (although they are more clearly defined than in previous campaigns), which also changed over the course of the war, have also contributed to the disputes and uncertainty regarding the war. The two objectives of the war—returning the hostages and dismantling Hamas—also add to the complexity. Moreover, it is also difficult to distinguish between actual victory and the public’s perception of victory, complicating any declaration of victory. Our analysis is based on both the findings of surveys conducted by the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) in the first three months of the war,[1] as well as an examination of the public and media discourse in Israel.

In a reality marked by both a commitment to continue the war until its objectives are achieved and an inability to fulfill these objectives as they are conveyed to the public or to create a sense of triumph, there is a danger of becoming entrenched in the conflict without a discernible exit strategy and of continuing combat without understanding its purpose. Such a scenario could have severe repercussions on the IDF and Israeli society.

Old Concepts, New War

Over the past few decades, with the conclusion of the Cold War and the decline in the risk of wars between states (until the Russia–Ukraine war in 2022), military thought in Western states began to focus on the issue of victory in campaigns against sub-state actors—terrorist and guerrilla groups and “hybrid armies” that have evolved, including some along Israel’s borders. In relation to such adversaries, basic concepts that were useful for confrontations between states, including “deterring, forewarning, and defeating,” and which were the foundation of Israel’s national security concept seem to have lost their validity. The situation became more convoluted as state systems, including political echelons and military forces, did not change. Their conceptual and organizational efforts were entirely dedicated to finding ways to adapt old tools to the new confrontations. It is difficult to say that any Western state, including the United States and its various coalitions, along with Israel, achieved any real success in doing so.

In his seminal work, The Utility of Force (2005), the British general Sir Rupert Smith claims that one difficulty stems from the political and journalistic rhetoric that accompanies the war from its onset is still framed as a struggle between states. According to Smith, this causes confusion regarding the utility of force. When entering a conflict, the declared intentions include explicit strategic objectives of “going to war” in the industrial sense, but the actions and results are all sub-strategic and relate to the world of armed conflicts and confrontations. He also posits that the media is still stuck in the paradigm of industrial warfare and does not understand or recognize that warfare is now among people. In other words, the definition of victory in war is determined by politicians and communicated by the media using familiar terms from the “great” wars, such as “defeat” or “downfall,” and illustrated with terms of action—conquering territory, killing enemies, or destroying a city. But when a battalion of a terrorist or guerrilla army that had been reported as having “collapsed” essentially splits into hundreds of cells that continue to fight in conditions most convenient for them, then both conquering territory and remaining in it over time shift from being a means of defeat to becoming a problem of its own (such as, for example, Israel’s occupation of southern Lebanon), and the destruction of a city serves the enemy in its cognitive warfare against the power stronger than it. The public—in this case, the Israeli one—also perceive “defeat” and “downfall” as empty phrases whose actual implementation is difficult to envision.

The discussion of these concepts began in the IDF in the 1990s, leading to debates between ranking officers and external experts in the early 2000s, such as at the conference titled “Between Decision and Victory” that took place at Haifa University in January 2001. IDF chiefs of staff convened “victory workshops” in which senior officers discussed definitions to guide their actions. In the 2015 the IDF Strategy document, Chief of Staff Gadi Eisenkot referred to the “decisive approach,” which aims “to change the strategic situation” and is “expressed by the enemy’s inability and/or unwillingness to act against us, and inability to defend itself.” The IDF’s expectation, he added, was a “quick and decisive victory.”

The difficulty in defining victory against a terrorist organization was apparent already in the military action during the First Intifada in 1987, when Chief of Staff Dan Shomron stated that “there is no military solution” in response to the uprising. This challenge became even more apparent during the military campaigns of the first decade of the 21st century, from the Second Lebanon War to the rounds of confrontation in the Gaza Strip. Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, in his speech to the Knesset on July 17, 2006, presented five objectives in the Second Lebanon War: implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1559, the unconditional return of the kidnapped soldiers (the late Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev), the dismantling of Hezbollah and the cessation of the threat of missiles on Israel, the deployment of the Lebanese army along the border with Israel, and the imposition of the Lebanese government’s sovereignty throughout its territory. Although it was clear that the fighting would not achieve these aims (regarding the hostages, it was stated explicitly to Olmert that they would not be returned, and he responded that he knew that their return could not be achieved through combat, but that he needed to present this objective for moral reasons), the Israeli press praised Olmert’s speech. Eitan Haber even wrote in Yedioth Ahronoth, “If it was not forbidden by the Knesset by-laws to applaud, it’s almost certain that at the end of the prime minister’s first speech during the war, the members of Knesset would have given him a standing ovation.”

The disappointment in the results of the war, which cost Olmert a great deal of his public support and led to the dismissal of the chief of staff and the head of the Northern Command, was reflected in statements made by their successors during subsequent rounds of fighting in the Gaza Strip. That is how the Israeli public came to learn such vague definitions as “Hamas controls Gaza but is deterred and restrained” during Operation Protective Edge, and why the public expressed a degree of cynicism at every bombastic declaration made by a politician or journalist. In a state that grew out of the myth of the decisive victory of the Six-Day War, and the change in the military situation after the surprise of the Yom Kippur War, the public’s expectation for a “quick and decisive victory” over enemies much weaker than the Egyptian or Syrian armies of that time did not disappear. When such a triumph was not achieved, the public’s frustration only grew.

Furthermore, it should be understood that in war against sub-state actors, such as Hamas or Hezbollah, they perceive their persistence and refusal to surrender to Israel as a victory, given the asymmetry of forces and capabilities between them and Israel. Hamas and its leaders adhere to the concept of sumud, “steadfastness” in Arabic. The populations among which Hamas operates or targets also support this view, enabling Hamas to amplify its achievements. In contrast, statements made by Israel’s leaders and senior military officers that Hamas will be definitively defeated strengthen the Israeli public’s expectation of a victory. Given its unrealistic nature, this expectation leads to frustration and creates a reality in which losing is almost certain.

“We’ll Win Together”

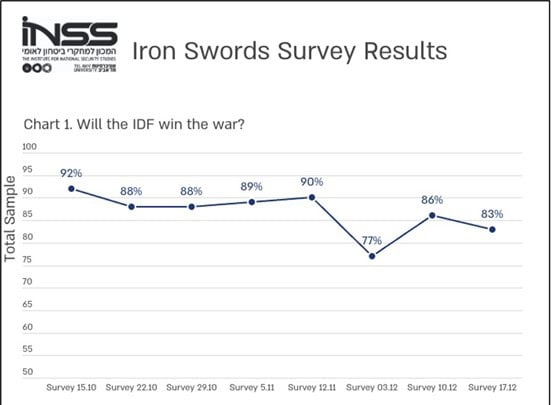

Despite—and perhaps because of—the shocking and unprecedented military failure in preventing Hamas’s surprise attack on October 7, alongside the Israeli public’s immediate exposure to distressing images via social media, the prevailing sentiment at the outbreak of the war was that the IDF would be victorious and would decisively defeat Hamas. The public discourse reflected this sentiment as did the informal public campaign of “We’ll win,” alongside one for unity, bearing the slogan “Together We’ll win,” which connected the clear expectation of an unequivocal victory with the wish for Israeli society to heal itself from the severe political rift that occurred throughout 2023. The surveys carried out from the first week of the war onwards reflected this perspective and indicated that the general attitude was that “the IDF will win” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Will the IDF win the war?

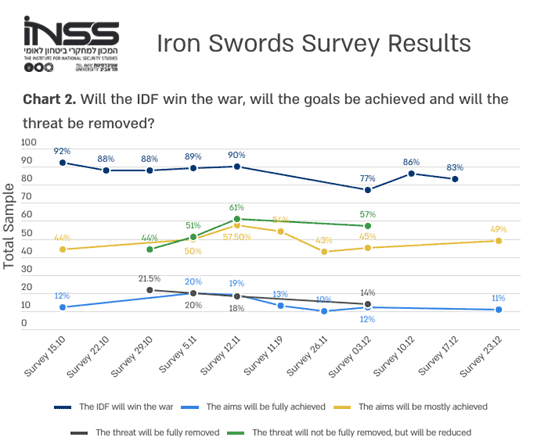

This attitude primarily reflects the Israeli public’s need to believe that the IDF will win, especially after the atrocities of October 7, and to feel secure and defended. However, it does not necessarily reflect a thoughtful and reasoned assessment of the army’s capabilities, nor a deep understanding of what would be required for the end of the war to be defined as a “victory.” This familiar sentiment has been deeply ingrained in the public throughout Israel’s history and is reflected by the public’s high degree of trust in the IDF (see, for example, the trust index of the Israel Democracy Institute) to carry out its operational missions (in contrast to lower levels of trust with regard to internal affairs). The surveys reveal a significant disparity between the high rate of respondents who believed that the IDF would win, and the lower rate who believed that the objectives of the fighting in Gaza would be met or that the security threat to the western Negev would be removed entirely or reduced (see Figure 2). It is thus important to understand what that victory, which the media campaigns and public sentiment suggest we should achieve together is, as well as determine how we will know that it has been achieved.

Figure 2: Will the IDF win the war, will the aims be achieved, and will the threat be removed?

War Objectives

One way to define victory in a military campaign relates to achieving its objectives. In contrast to previous rounds of combat with Hamas, during which the war objectives tended to be vaguely defined—such as “restoring deterrence”—the Swords of Iron campaign had defined objectives from the outset, although their definitions went through several changes over time. During the first days of the war, the objective discussed was to topple Hamas. It was stated repeatedly that this was not another round of fighting or an operation to restore deterrence but rather the aim is toppling the terror organization and its destruction. On the eve of October 7, Prime Minister Netanyahu declared that “the IDF will act immediately with its full strength to eliminate the capabilities of Hamas. We will strike them until destruction, and we will forcefully avenge this black day that they brought upon the State of Israel and its citizens.” In his speech during the swearing-in of the emergency government, which brought the National Unity party into the coalition, Netanyahu focused on toppling Hamas and emphasized, “We will fight with full force the accursed murderers, the bestial predators, we will defeat them, we will erase them from the face of the earth. And at the same time we will rebuild the communities that were destroyed, we will restore the Gaza border communities, and we will turn it back into a thriving and beautiful region.”

The position and importance of the question of the hostages as one of the war objectives underwent a significant change over time, indicating the influence of public opinion and media support for the campaign of the hostage families, as well as political changes. The prime minister’s initial statements did not mention the hostage issue; on October 16, nine days after the start of the war, the War Cabinet (which had been established several days earlier when the National Unity party entered the government) authorized four objectives for the war. According to the media coverage, the objectives are:

- Toppling Hamas rule and destroying its military capabilities

- Removing the terror threat from the Gaza Strip on Israel

- Maximum effort to solve the hostage issue

- Defending the state’s borders and citizens

The use of the words “maximum effort” does not translate into a commitment nor suggests that returning the hostages it high on the list of priorities and considerations in the decision-making; many statements in the press also presumed a contradiction between defeating Hamas and returning the hostages. As time went on and the public pressure increased, the statements on this issue became clear and unequivocal—the aims of the war are toppling Hamas and returning the hostages to Israel.

Thus, for example, on December 20 in the tenth week of the war, the prime minister stated “We will not stop fighting until we achieve all the aims that we set: eliminating Hamas, releasing our hostages, and removing the threat from Gaza.” Minister of Defense Yoav Gallant also made several declarations along these lines. After the incident in which an IDF force mistakenly shot and killed three hostages who had managed to escape from captivity in Gaza, Minister of Defense Gallant stated, “We will continue working until we achieve the aims of the war: toppling the Hamas regime and bringing all the hostages home.” In the military echelon, both the IDF Chief of Staff and spokesperson have regularly referred to those two objectives.

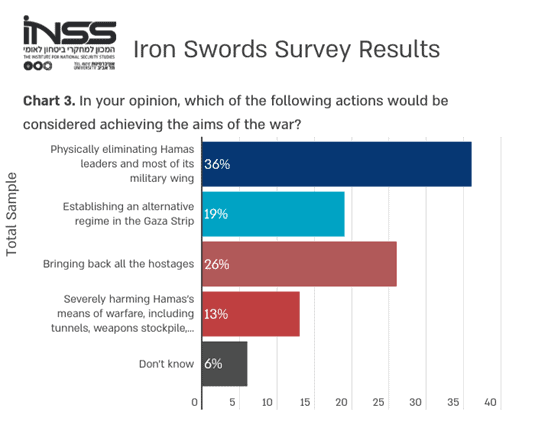

The changes that occurred in the definition of the objectives of the war reflect the trends in public opinion. Although it may seem that the objectives are defined and focused, there is still significant difficulty in understanding what exactly they include. In the fourth week of the war, we asked respondents in an INSS survey what did they consider to be achievements in realizing the objectives of the war (see Figure 3). The most common answer among the respondents was physically eliminating Hamas’s leaders and most of its military wing (36%). The second most common response was bringing back the hostages (26%) and the third was establishing a different regime in Gaza (19%). In the fourth and last place was seriously damaging Hamas’s means of warfare, including tunnels, weapons stockpile, and rockets (13%). As the war continued, the public discourse focused on two of the war aims: bringing back the hostages and toppling the Hamas regime.

Figure 3: In your opinion, which of the following actions would be considered achieving the aims of the war?

From the beginning of the war, the precise meaning of “toppling” Hamas has been subject to discussion. The meaning of bringing back the hostages, ostensibly a clearer and more defined objective, has also been questioned. In further defining this objective—to what extent should Israel work to bring the hostages back alive—it was clear that some of the hostages held by Hamas were already dead on October 7, and that as time passes this will be the case for more hostages. As of mid-February, at least 30 hostages are reported to have died, and the campaign led by their families for their release has increasingly emphasized that every day in captivity endangers their lives.

The official rhetoric of the State of Israel emphasizes that it is committed to bringing back the bodies of its soldiers and civilians in order to give their families closure, as it repeatedly stated about IDF soldiers Hadar Goldin and Oron Shaul, whose bodies are being held by Hamas. The IDF’s actions during the current campaign also indicate that it is committed to bringing back bodies and acts toward this end. However, in this war, for the first time, Israel must address the dilemma of how much the well-being of the living hostages, or those whose fates are unknown, should limit the manner of combat.

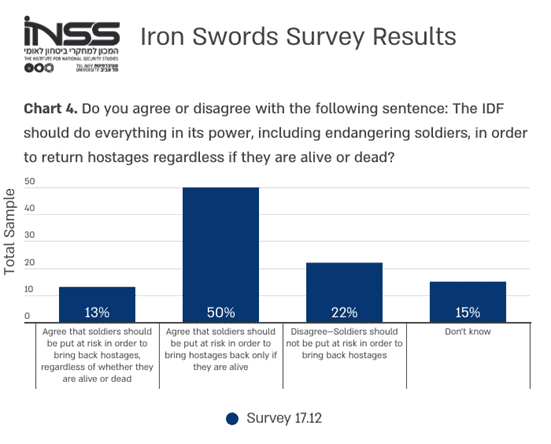

We asked respondents in a survey on December 17, six weeks into the war, whether they agreed or disagreed if the IDF should do everything it can—including endangering the lives of soldiers—to bring back the hostages, whether they are alive or dead (see Figure 4). Only 13% of the respondents said that soldiers should be put at risk to bring the hostages back whether they are alive or dead. In contrast, almost half of the respondents (49.8%) believed that soldiers should be put at risk to bring back hostages but only in the case in which the hostages are still alive. Accordingly, even in relation to this objective, which has widespread public backing, there is a certain lack of clarity about its precise meaning and the way in which the public perceives it.

Figure 4: Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: The IDF should do everything it can, including endangering the lives of soldiers, to bring back the hostages, whether they are alive or dead?

The objective of toppling Hamas is even more ambiguous. It is not clear how the achievement of this objective can be measured, because it has multiple components (eliminating the Hamas leadership, negating its military capabilities, negating its governing capabilities, and so on). There is also an inherent difficulty in defining the defeat of a terrorist group, which does not fit neatly into the traditional concept of defeat that relates to enemy armies. Furthermore, the lack of military defeat in the traditional sense allows Hamas to exaggerate the importance of its achievements, since Hamas, as a terrorist group, does not aspire to defeat Israel. Each day that Hamas persists and does not surrender to Israel constitutes a victory for Hamas. The public perception among the populations Hamas targets also reflects this perspective and enables Hamas to further emphasize their accomplishments. In contrast, Israel’s expectation that it must totally defeat the enemy causes a sense of frustration about the lack of an achievement.

As for the relationship between the objectives and their prioritization, despite the efforts by the government and the security agencies to claim that the war objectives complement one another, and that increasing military pressure on Hamas also serves the aim of bringing back the hostages, the public—and primarily the families of most of the hostages—have increasingly been convinced that the two aims cannot both be achieved, and that they must be prioritized. This feeling has become stronger as the ground maneuver in the Gaza Strip continues, along with increasing reports of hostages who have died in captivity. This understanding was reflected most clearly in a quote by Minister Gadi Eisenkot who said, in one of the cabinet meetings:

We need to stop lying to ourselves, to show courage, and make a large deal that will bring the hostages home. Their time is running out and every day that goes by endangers their lives. There’s no reason to blindly continue with the same formula we’ve been using while the hostages are still there, it is a critical time to make brave decisions, otherwise we have no reason to be here.

It should also be noted that as time went by, and especially after the deal to bring back most of the women and children hostages and pause the fighting, this contradiction has become part of the identity-politics debate in Israel, which had quieted down following the shock of the events of October 7, and then resumed, despite the “We’ll win together” campaign. The prime minister has emphasized, including in a special session of the Israeli Knesset that was held on December 25, that soldiers and bereaved family members have implored him “to continue with full force.” During meetings he held with families of hostages, representatives of other families were especially brought in and claimed that Israel should not stop the fighting even if it was likely to harm their loved ones. The media (especially on Channel 14) even made an attempt to classify the hostage issue as “a left-wing issue” as opposed to “the soldiers” who want victory and continued fighting, and who are identified as right-wing.

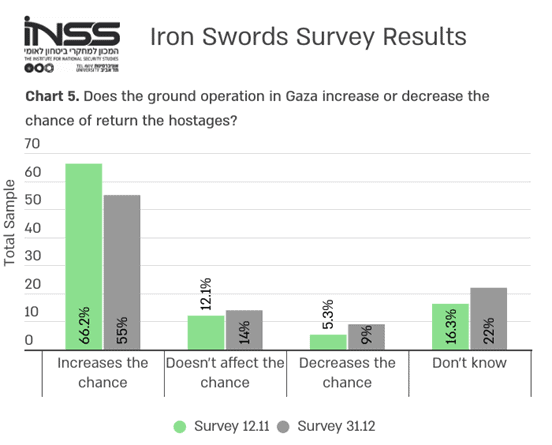

How is this reflected in INSS surveys? In the survey conducted on November 12, not long after the beginning of the ground invasion, some two-thirds of respondents (66.2%) stated that the ground invasion in Gaza increased the chances of bringing back the hostages. However, in a more recent survey carried out on December 31, only 55.3% of respondents believed that to be the case—although it still reflects over half of the public (see Figure 5). The decrease in public support for the ground invasion as increasing the chances of returning the hostages is likely to continue as long as the issue remains the focus of political polarization.

Figure 5: Does the ground invasion in Gaza increase or decrease the chances of bringing back the hostages?

Given the need to prioritize between the aims of the war, the change in public sentiment regarding how they should be prioritized is noteworthy. When we asked in our survey on December 3 if the respondents thought it was acceptable to bring back all the hostages in exchange for a massive release of Palestinian prisoners, including participants in the October 7 massacre, and for a cessation of the war, more than half of participants (60%) answered that this would not be acceptable to them. Two weeks later, in our survey on December 17, 50.2% opposed such a deal. While the majority of the Israeli Jewish public prioritizes toppling Hamas over bringing back the hostages, it appears that as time goes on, this prioritization could change among a greater segment of the public, either because their priorities have changed, or because they have become convinced that one aim is more realistic than the other.

Between Victory and an Image of Victory

When discussing the question of victory, a distinction must be made between two different meanings of victory. The first is victory in the military sense. That is, we can ask to what extent did the campaign achieve its aims as presented by the political echelon to the military echelon. This meaning of victory is measurable to the extent that the aims and objectives of the war are measurable. For example, we can ask what percentage of Hamas troops and infrastructure were destroyed, how many hostages were brought back, to what extent was the political strength of Hamas weakened, and so forth. The second sense relates to the perception of victory and can be divided into two components: the Israeli public’s perception of victory and the external perception of victory by Israel’s other enemies and how the international arena perceives the achievements of the campaign.

Given that the Israeli public perceives the current war as an existential one and the majority of the public perceives it as a just war—with the October 7 massacre removing any doubt as to the war’s justness—the need for victory in this war is even more pressing than in previous confrontations. During previous rounds of fighting in Gaza, for example, even if victory was not achieved in its explicit sense, it was not necessarily a threat to the State of Israel. The public perceives the current military campaign differently and expects it to continue until achieving an image of victory or reaching achievements can constitute victory in this campaign.

The achievement of military victory in this campaign is more complex than it was initially presented, given the difficulties of achieving victory over a sub-state actor, in addition to dealing with Hamas’s combat strategy and its extensive use of the underground tunnels and spaces exceeding what Israel had been aware of before the war. The increasing international pressure on Israel also limits the leverage that Israel can exert against Hamas.

An additional danger relates to the measurability of the image of military victory, given the desire to present achievements that will be perceived or will appear to be a victory. The definition of victory in military terms is achieving the objectives of the war. In the absence of being able to indicate clear achievement of the aims—and insofar as these are not measurable, this is almost an inherent result—the tendency will be to frame tactical achievements as comparable to victory or bringing us close to victory. From this pattern, for example, arose the need to report on the number of terrorists killed, the number of Air Force attacks, and the number of enemy battalions that were almost completely destroyed; however, these reports do not necessarily generate a sense of achievement or victory. Instead, their reliability is questionable, as it is clear to the public that stating an exact number of terrorists that were killed is implausible, because they cannot be accurately counted, especially in a reality in which many casualties are in Gaza’s underground tunnels. In addition, the number of casualties suffered by the enemy gradually loses significance, as it is the losses among the IDF troops, such as when 21 soldiers were killed in an explosion of a building, that influence the public mood, creating a sense of despondency. The outputs, such as Air Force attacks, do not create a sense of accomplishment but rather frustration, given that these attacks are perceived as having minimal effect for such a large effort. These issues are reminiscent of the American “body count” during the Vietnam War, which did not manage to change the Americans’ sense of failure in that war.

Furthermore, even if military victory is achieved, it may not be accompanied by the perception of victory. The perception of victory is crucial and is almost as important as the victory itself for several reasons. First, in relation to the current war, the perception of victory is critical for returning the residents of the Western Negev (and in parallel, the residents of the North) to their communities. Second, in the context of this war which began with a notable failure, establishing a clear sense of victory is crucial to impress our triumph upon the enemy. If this is not achieved, it will be difficult or impossible to restore the IDF’s deterrent capabilities, which had collapsed on October 7. This is paramount both against Hamas and against Israel’s other adversaries that are closely monitoring the war’s development and the IDF’s performance. Furthermore, cultivating a perception of victory is key to restoring the public’s trust in the IDF and bolstering Israel’s social resilience, both which were severely harmed by the October 7 massacre.

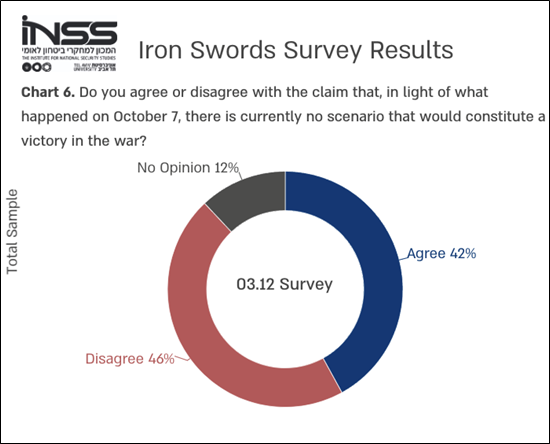

Achieving a perception of victory will be especially difficult in the present campaign, given the blow that Israel suffered at its start, and which led a significant segment of the public to believe that there would be no possible victory in this campaign because of the way in which the war started. In a survey conducted by INSS on December 3, 41.9% of respondents indicated that they agreed or mostly agreed with the claim that given what happened on October 7, there was no scenario that would constitute victory (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Do you agree or disagree with the claim that given the events of October 7, there is currently no scenario that would be considered victory in the war?

Furthermore, the starting point of the current campaign created a desire for revenge among some segments of the Israeli public, leading to objectives and goals that were not only unrealistic but also unacceptable under international law and failed to garner international support for Israel. Consequently, these segments of the public might not believe that victory has been achieved, even if the war ends with a significant military success for Israel.

The issue of bringing back the hostages also casts a shadow over the perception of victory. As time passes and more hostages are declared dead, it will be increasingly difficult to convince the public that returning the bodies of hostages represents a significant achievement, which is necessary for creating a perception of victory. Moreover, if a large number of hostages are released, it likely will not be the result of a military action but rather due to a deal made between Israel and Hamas. Such a deal is likely to include significant and generous Israeli concessions, which will make it more challenging to “sell” to the Israeli public as an achievement that constitutes victory.

Cultivating an “image of victory” is one strategy to foster a sense of triumph, and it warrants discussion. At times, the perceived and actual image of victory align; however, the pursuit of an image of victory might prompt decision-makers to prolong the campaign unnecessarily through both military and diplomatic efforts. This could compromise the balance between the different needs and could potentially lead to misguided military moves under the pressure to produce such an image. Moreover, the difficulty of accurately deciding which weight should be given to public expectations, which are themselves often misunderstood, can result to mistakes in deciding when to end the combat or to move into its next phase.

The external perception of victory is critically important and should not be overlooked. It significantly influences the IDF’s deterrence capability, particularly should an additional front open simultaneously with the war in Gaza. Although not an official goal of the campaign, senior Israeli officials have indicated that the combat in Gaza serves as a deterrent, signaling to adversaries that attacking the State of Israel and its citizens, particularly a scale like that of October 7, will lead to grave consequences. Israeli spokespersons have repeatedly emphasized that if Hezbollah attacks Israel, Lebanon will share the same fate as that of the Gaza Strip. Ending the campaign in Gaza or even its critical combat phase, with a perception that the IDF has been defeated, could drastically weaken Israel’s deterrence capabilities.

Conclusion

The concept of victory in modern conflict is both crucial and elusive, sparking debate among both practitioners and the public alike. This debate often includes political discussion on how to adapt traditional concepts of war—originally designed for large-scale war with state actors—to asymmetric wars against terrorist organizations.

The war in Gaza is an extreme case. Its aims are not questioned; rather, the public debate focuses on the approach to the war and growing doubts that the aims can be achieved, alongside the sense that this war will not be won, despite the traumatic events that triggered it. The political rhetoric, especially from officials who will be held accountable for the events of October 7—who remain in office to much controversy—exacerbates the issue.

Surveys conducted by INSS since the war began reveal the public’s diminishing sense of achievement as the war continues, with a growing concern that Israel will not win the war. This growing sense of defeat will affect people’s personal sense of security. The intense focus on the hostage issue highlights a broader dilemma: although the war is widely seen as justified, the challenge of defining and achieving victory have almost become a moral litmus test for Israeli society.

These developments underscore the need for a leadership in Israel that is transparent and sincere and that communicates the facts, alternatives, and choices made clearly and honestly. The surveys reveal the lack of public trust in the current political leadership, exacerbated by grandiose statements about “absolute victory.” This situation raises concerns that the possibility of achieving a perception of victory in the war, deemed essential by most Israelis, may be slipping away.

________________

[1] These surveys were based on a representative sample of 500 respondents from the adult Jewish population in Israel. The surveys were conducted weekly between October 12 and December 31, led by the INSS Analytics Desk. The fieldwork was carried out by the Rafi Smith Institute using internet questionnaires. The mix of questionnaires included a series of consistent questions as well as questions on a variety of subjects that changed each week. The margin of error for the sample was +/- 4% with a 95% confidence interval.