The Operational Environment: Possible Escalation to an Unwanted War

Itai Brun and Gal Perl Finkel

Snapshot

Israel’s enemies are deterred from large-scale conflict · Possible unwanted escalation in the north and south · In a war Israel will sustain a severe attack on the home front, an incursion into its territory, and a cognitive campaign

The Operational Environment: Possible Escalation to an Unwanted War

Itai Brun and Gal Perl Finkel

Recommendations

Prepare for a multi-theater war (“the northern war”) · Budget a multi-year plan for the IDF, suited to post-pandemic budgetary constraints · Remove the IDF and security establishment from the political struggle

Israel’s enemies are aware of its strength, preoccupied with their own domestic problems, and eager to avoid escalation. However, war in 2021 is possible – in the northern arena and Gaza – following a “dynamic of escalation.” In a war, the IDF would employ lethal offensive capabilities on the ground, in the air, at sea, and in the cyber realm, and inflict considerable damage on its enemies. But in such a war, Israel would likely face massive surface-to-surface missile and rocket fire on the home front, and attacks by UAVs and drones. The penetration of ground forces into Israel’s territory is also expected, as well as cyber and cognitive attacks to undermine the public’s stamina and its confidence in the political and military leadership. Consequently, it is necessary to prepare for the next war, including by setting clear expectations on the part of the public regarding the nature of the war, its costs, and what it will demand of the public.

The complex and challenging operational environment where Israel employs its military force (along with other measures) represents the convergence of technological, military, social, and political developments that emerged over recent decades. These developments include: deep, global changes in the nature of war; geostrategic changes in the Middle East, most of which are connected to the consequences of the regional upheaval and the ensuing events (including the arrival of Russian and US military forces in the region); substantial changes in the operational doctrine and weapons of Israel’s enemies, especially those that belong to the radical Shiite axis; changes in how Israeli military force is employed, and the preference for firepower (based on precise intelligence) over ground force maneuvers; and the consequences of the information revolution that has shaken the world, including the military institutions.

From Isolated Battle Days to Escalation?

In 2020 Israeli deterrence of large-scale conflict and war remained clearly in force, and even seems to have grown stronger. Israel’s enemies recognize its strength, and they are preoccupied with their domestic problems, including the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. A series of war games held by INSS in late 2019 and early 2020, before the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis, led to the conclusion that all of the actors in the northern arena wish to avoid escalation. The year 2020 validated this assessment, and indeed, escalation did not occur. The experience of the last few years shows that this is also the case with regard to forces in the Gaza Strip.

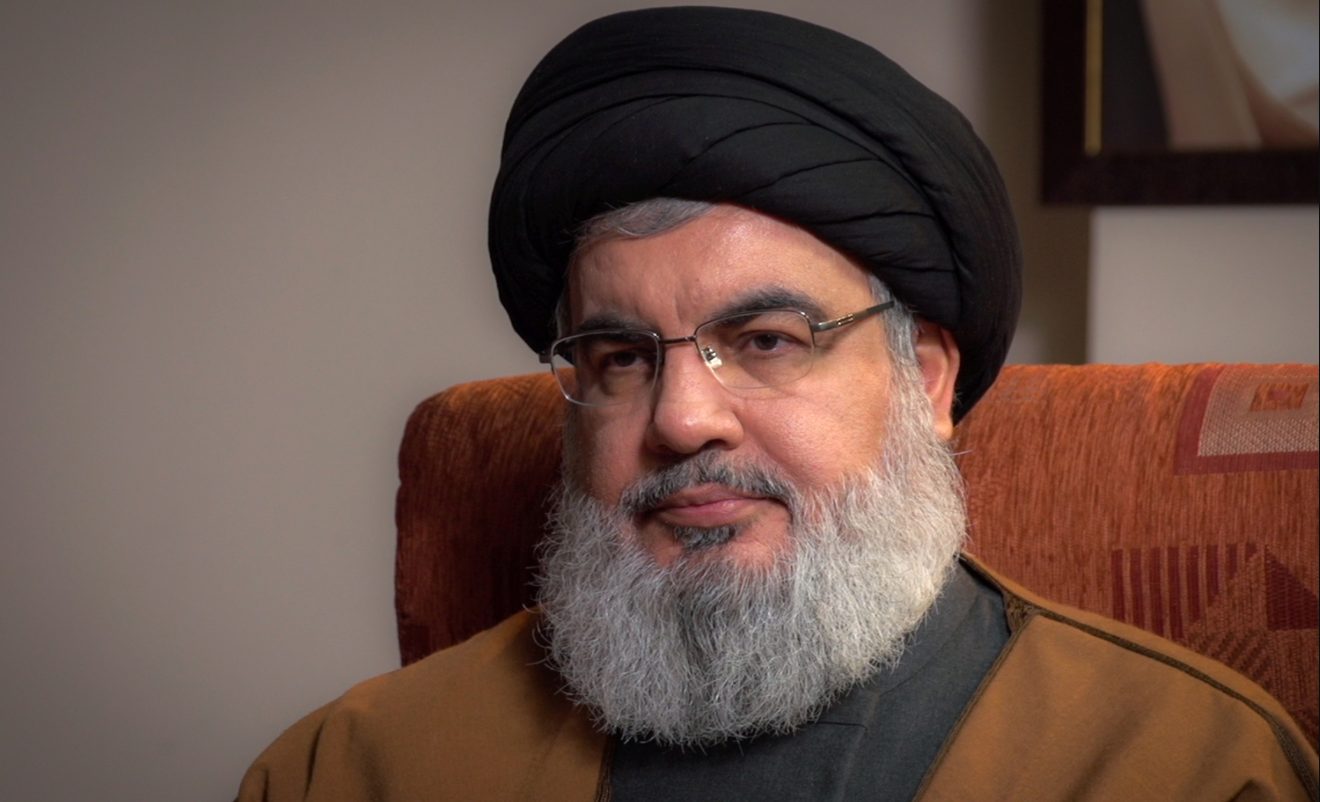

The actors in the northern arena prefer to avoid escalation. Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah

Photo: Website of the Iranian Supreme Leader

However, since last July, the Northern Command has been on a higher level of alert with respect to Hezbollah, following Hezbollah’s threat to respond to the strike attributed to Israel in Syria in which one of the organization’s operatives was killed. The organization tried several times to settle the score with Israel, but was unsuccessful. The IDF repelled all of the attempts and even continued its attacks in Syria, in a way that made it clear that it does not accept the deterrence equations composed by Hezbollah.

In Israel, as in the ranks of Hamas and Hezbollah, there is an awareness of the danger inherent in an escalation dynamic, but it seems that all of the sides expect that they can end it after a few days of battle, similar to the short conflicts in the Gaza arena in recent years. However, such a scenario could change if one or both of the sides suffers fatal losses, at which point response and counter-response could escalate and lead to large-scale conflict and even war. Such a war could occur with the Iranian-Shiite axis, including Hezbollah in Lebanon, Iranian proxies in Syria and Iraq, and perhaps even with Iran itself. Furthermore, the escalation could spill over into other arenas, in particular with the forces in the Gaza Strip.

The Enemy’s Operational Doctrine

Hezbollah and Hamas’s choice regarding their current form of warfare stems from learning processes that took place starting in the 1990s, based on an analysis of Israel’s strengths and weaknesses. Last year INSS pointed to a change in these organizations’ doctrine of warfare following lessons learned from the conflicts that developed with Israel since the Second Lebanon War (2006). The essence of this change is the transition from a victory concept based on wearing down the Israeli population (“victory via non-defeat”) to a concept that also seeks to damage, from various arenas, national infrastructure in Israel and essential military capabilities, in order to destabilize and undermine the Israeli system.

If there are fatalities, isolated days of battle are liable to escalate to a large-scale conflict. Exchanges of fire between the UDF and Hezbollah in the Mt. Dov area, July 2020

Photo: REUTERS/Karamallah Daher

This concept is implemented by means of military buildup processes that include: increasing the number of rockets and missiles, both in order to improve the survivability of the arsenal and to saturate the Israeli air defense systems; arming with high-precision rockets and missiles that can hit vulnerable civilian facilities (electricity, gas, and other national infrastructure) and military weak points (air force bases and headquarters) in Israel; arming with drones and other unmanned aerial aircraft, including for the purposes of precision strikes.

This concept is also based on the idea of infiltrating ground forces into Israeli territory, in order to disrupt the IDF’s offensive and defensive operational capabilities and to increase the damage to the home front’s stamina. Against this backdrop, the abilities of Hezbollah and Hamas to penetrate into Israeli territory have been improved, including in the underground realm, via special raid forces (Hezbollah’s Radwan force and Hamas’s Nukhba force). These forces are intended for moving some of the fighting into Israeli territory – taking central roads, infiltrating communities and bases, and compelling the IDF to invest a significant portion of its efforts in defense – in effect preventing it from being able to go on the offensive. Hamas has invested significant efforts and resources, both material and personnel, in its offensive tunneling project. In October the IDF exposed and destroyed an especially deep border fence crossing tunnel that was located using the engineering barrier capabilities built along the border between Gaza and Israel. It seems that Hamas has not abandoned the project since the construction of the barrier, and intends to find ways to overcome the obstacle.

The IDF Operational Doctrine

An examination of public official IDF documents published during the past year reveals a great deal about the concept of the IDF operational method in the next campaign. Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Aviv Kochavi and the entire General Staff see the response as a combination of “multidimensional maneuver into enemy territory, offensive strikes using firepower and other dimensions, and strong multidimensional defense. All of these will be carried out together, will benefit from closer reciprocity, and will fully utilize their advantages in the air, on the ground, in intelligence, and in information processing in order to expose the hidden enemy and destroy it at a fast pace.”

Hamas is investing heavily in the development of attack tunnels. A terror tunnel uncovered along the Gaza Strip border

Photo: REUTERS/Jack Guez

Along with investing in enemy exposure capabilities and increasing fire effort capacities (with an emphasis on precision fire), the IDF has invested efforts in the ground forces in order to make ground maneuver more lethal, faster, and more flexible. In addition, the IDF has invested in constructing an engineered barrier, both on the northern border and in the southern arena, with the aim of thwarting the offensive tunneling efforts by Hamas and Hezbollah.

Regarding firepower, with an emphasis on airpower, the IDF has developed its strike doctrine on a large scale and with great precision, with each such strike aiming to cause the enemy destruction and damage that will exceed its expectations regarding the IDF’s capabilities and intentions. These strikes will be directed toward hitting enemy systems that it defines as critical to its operational functioning and to implementation of its strategy. There are three kinds of strikes: spatial strikes, whose goal is to hit a maximum number of the enemy’s operatives, infrastructure, and weapons in a given sector; mission-oriented strikes, whose goal is to destroy a specific enemy system (long-range rockets, for example); and broad strikes, whose goal is to hit a series of systems and spaces in order to cause the enemy to suffer multi-system failure and force it to invest most of its efforts in defense and repair of the destruction it has suffered. The goal of neutralizing warfare capabilities focuses on the enemy’s rocket arsenal, with an emphasis on the precision long-range missile arsenal, along with the operatives in its penetration forces.

Regarding ground maneuvers, in recent years two main gaps have emerged according to the IDF’s assessment, both in its ability to meet the challenge of high-trajectory fire in different arenas, and in the ability to deny capabilities in the enemy’s centers of gravity quickly and continuously. Thus, the army formulated an up-to-date doctrine for ground maneuvers that aims to address these gaps and sees maneuver warfare as a multidimensional process. In the ground forces, the maneuver doctrine has been formulated emphasizing consolidation, exposure, assembly, strike, and assault, whereby the maneuvering forces will be provided with intelligence capabilities and enhanced enemy exposure capabilities. This is so that they can attack the enemy and neutralize its capabilities, through both precision fire and rapid and lethal maneuvers. The IDF prioritization of firepower remains, but it is evident that in the past five years the understanding has emerged that launching fast and aggressive maneuvers as a complementary step is essential for quickly ending the campaign, under conditions that will serve Israel’s interests. Accordingly, considerable resources have been invested in improving and strengthening the capabilities of the maneuvering forces.

The Nature of the Next War

The IDF must prepare for two main campaign scenarios that could develop from unwanted escalation following limited battle days in the northern arena: a “third Lebanon war” with only Hezbollah in Lebanon that would be much more intense and destructive than the Second Lebanon War; and a “first northern war” with Hezbollah in Lebanon, but also with forces in Syria and Iraq, and perhaps also in Iran and in additional arenas.

The IDF recognizes that rapid, aggressive maneuver is essential to a quick end to the war. IDF ground forces in a military exercise

Photo: Staff Sgt. Alexi Rosenfeld, IDF Spokesperson’s Unit – CC BY-NC 2.0

In a war, the IDF would employ its offensive capabilities – on the ground, in the air, and at sea – and would cause very extensive damage to its enemies, in the front and deep behind enemy lines. But in such a war Israel too is expected to face massive surface-to-surface missile fire on the home front, some of which would be precision missiles and some of which would even penetrate the air defense systems. There would be attacks on the home front by unmanned aerial vehicles and drones; the penetration of ground forces into Israeli territory on the level of thousands of fighters; and cyber and cognitive attacks intended to undermine the stamina of the Israeli public and its faith in the political and military leadership. The IDF’s offensive components would face sophisticated air and sea defense systems and complex ground defense systems, including the use of the underground realm and advanced anti-tank missiles.

The campaign could therefore take place on two different levels: on one, Israel’s enemies would attack the home front with high-trajectory fire in amounts not previously seen, and in the other Israel would attack the enemy’s forces in its territory, through firepower and through ground maneuvers. But it is possible that the impression will emerge of only a loose connection between the two levels. Given the destruction in Israel’s cities, Israel’s residents who will be under fire will not be overly impressed by the enormous destruction that the IDF will inflict on the enemy’s systems (even if they are located within a civilian population) and by the number of its operatives who are struck in the battles. Battalion commanders in the Second Lebanon War said that during the fighting, despite lapses and errors, they felt that they carried out their mission and won overall, and when they returned to Israel they discovered that the public thought that the achievement lay somewhere between a tie and a loss. Considering the expected damage in the next war, this feeling will intensify.

Furthermore, presumably the reserve forces that are called up will also be forced to organize under fire, as the recruitment bases and emergency storage units will be targeted. The army will not be able to implement its “precious time” doctrine, whereby during a conflict the reserve units go through training to increase their fitness and only then take part in the fighting, because the training areas will also be targeted (as they were in 2012, during Operation Pillar of Defense in the southern arena). Moreover, because some of the bases of reserve units are located far from the front lines, transporting the forces could be delayed due to high trajectory fire by the enemy. Hence, the safest place that the fighting forces can be is at the front and in the depths of enemy territory. While the ground forces will have to cope with the risks of fighting there, their combat capabilities and strength will address these risks.

The Israeli public expects a military victory in a short campaign with few losses. This expectation grows when it comes to a campaign based on the use of airpower. However, in future conflicts it is expected that the air force squadrons will not be able to move almost freely over enemy territory, as was demonstrated in February 2018, when, during an Israeli air strike in Syria, an F-16 fighter jet was hit and its pilots were forced to abandon the aircraft over the Jezreel Valley. Furthermore, along with its anti-aircraft systems, the enemy will seek to damage the functional continuity of the Israeli Air Force by firing rockets and missiles at air bases. The IDF will need to struggle for air superiority and freedom of operation. Moreover, the Russian presence in the northern arena could place additional limitations on the air force’s freedom of operation.

Policy Recommendations

Israel must prepare for a multi-theater war (a “northern war”) as a main reference threat. This war would be characterized by a higher intensity than the campaigns that it has waged since the Second Lebanon War, both in terms of the amount of fire on the Israeli home front and in terms of the fighting front.

Given the challenges expected for airpower and the need to curtail fire on the home front quickly, it is important to prepare the ground forces for flexible, aggressive, and lethal maneuvers to destroy the enemy’s military force. In addition, it is important to narrow the gaps between public expectations regarding the nature and possible results of the war and the expected reality, and to initiate a political and military effort to prevent war and make the most of other alternatives for advancing Israel’s objectives in the northern arena. Furthermore, a multi-year plan for the IDF should be finalized and budgeted, and adapted to the budgetary constraints forced by the COVID-19 crisis. The buildup as part of the American aid should be implemented, and the IDF and the defense forces should be removed from the political struggle in Israel.