Publications

INSS Insight No. 1895, September 10, 2024

These days mark three years since the inauguration of the Bay Port in Haifa. Even before the port began its commercial operations in late September 2021, and even more so in the subsequent years, the port faced numerous challenges beyond those associated with operating a new port. The port’s operation by an Israeli company owned by a Chinese corporation drew extensive criticism in both Israel and the United States. The COVID-19 pandemic, a complex political reality in Israel, and a multi-front war that Israel encountered in 2023 also added to the difficulties. However, despite the dismay of its competitors, the Bay Port continues to operate and has been successful. This article reviews its establishment, the challenges it faces, and its level of success.

The story of the Bay Port began in 2013, with visits to China by then Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and later by then Minister of Transportation Israel Katz. Minister Katz signed an infrastructure cooperation agreement with China, which, among other things, led to the involvement of Chinese companies in the construction and operation of two new ports—the franchise to operate the Bay Port in Haifa and the construction of the South Port infrastructure in Ashdod. These ports were built as deep-water ports, allowing large ships to dock so that, according to the plan, Israel could integrate into the global geo-logistics map and possibly serve as a maritime hub for the Mediterranean basin and its countries.

However, there were not many bidders for the construction of the new ports, especially the northern one. Later, the US ambassador at the time testified about his efforts to recruit American companies to the tender, but his efforts were in vain. Eventually, Yona Yahav, then mayor of Haifa, approached the mayor of Shanghai, Haifa’s sister city, and asked him to interest the Shanghai International Port Group (SIPG) in the tender. SIPG operates the Port of Shanghai, the world’s busiest container port. For SIPG, the offer represented another attempt to expand beyond China after its failed venture in the Belgian port of Zeebrugge, by acquiring a port in an attractive geo-logistical location in a developed and democratic country. For Israel, the connection with SIPG meant bringing advanced port technology, previously unknown in Israel, including new operational machinery.

SIPG was the only group to bid on the tender and, of course, won it in 2015. However, the euphoria soon waned even before the company began operating the port. Before the start of its commercial work in late September 2021, the port encountered many difficulties, not only due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Objections raised by Haifa’s new mayor, Einat Kalisch-Rotem, caused delays in the construction of the infrastructure within the port itself, including attempts to change approved port plans, approving and paving roads to the port, and more. The election of President Donald Trump to the White House and his campaign against the “Chinese virus,” the US trade deficit with China, Chinese investments in infrastructure, and, in general, everything related to China, brought about an atmosphere of suspicion and even paranoia regarding Chinese involvement, especially in national infrastructure. This quickly led to a series of warnings from various entities in Israel about the potential problems the country could face as a result of its agreement to allow the Chinese to manage a port in its territory.

Criticism Against the Bay Port

At a conference held by the Maritime Policy and Strategy Research Center at the University of Haifa in 2018, it was claimed that the US Sixth Fleet would no longer dock at the Haifa Port because of Chinese involvement. Others argued that in the event of a security incident, the Chinese would halt operations at the port. Some even went as far as to claim that the Chinese would allow Iranian (or Chinese) warships to enter the port. Others took a more conservative stance, warning of the potential for Chinese espionage through the port’s systems. Regardless of the specific concern, critics argued that Israel had made a mistake and needed to rectify it. They demanded that the agreement with the Chinese be canceled and that they be removed from the port.

Despite the objections and criticisms, the Bay Port began its commercial operations in September 2021. As of the end of 2023, the port employed approximately 150 Israeli workers and about 20 Chinese workers. The COVID-19 pandemic allowed the Ministry of Transport to downplay the event of granting the port’s commercial operation approval by holding a modest Zoom ceremony that attracted little attention from the Israeli public and the US government. However, despite the critics’ concerns, it was quickly evident that the US government was less concerned about the port operator. A ship of the US Fifth Fleet (USS O’Kane) visited the port just a month after its opening, followed by a ship of the Sixth Fleet (USS Jason Dunham) four months later. Since then, more American naval ships have visited Haifa Port, including the USS Jason Sherman from the Atlantic Fleet in September 2022 and the USS Truxtun from the Fifth Fleet in January 2023. These visits disprove the claims that the US naval fleets would stop visiting Israeli ports and also reflect the minimal risk perceived by the American Navy at the Bay Port. Claims about allowing enemy ships to enter the port were also proven groundless, as the authority to approve or deny any ship’s entry into the port area is exclusively in the hands of the port owners, namely the State of Israel, through the Haifa Maritime Transportation Company. Meanwhile, like all Israeli ports, the Bay Port is subject to supervision by the security authorities, and so far, the authorities have not reported any difficulties or criticisms of the Bay Port.

Moreover, since the war with Gaza, a significant and extensive security event, the port has continued to function. The war has not disrupted nor halted the port’s activity, with the port even accommodating ships that could not or did not want to dock at Ashdod Port due to rocket fire from the Gaza Strip. Additionally, the port took some symbolic actions to support the Israeli economy and the war effort, including donating dozens of armored containers to the IDF, extending waivers on storage fees for importers, hosting a company of soldiers and officers from the Home Front Command (which included providing accommodation and meals), and conducting solidarity activities on behalf of the Israeli hostages held by Hamas.

Over the years, criticism toward the Bay Port has continued to surface occasionally, mainly from its competitors, who have used the port’s association with a Chinese company to amplify their claims against it, giving them a political and geo-strategic lever. For instance, in January 2024, the chairman of Ashdod Port sent a letter to the Shipping and Ports Authority calling to “revoke the Chinese company’s certification to operate the port during wartime and to cease inviting its representatives to regular updates that have been held since the start and are of a sensitive nature.” The chairman made sure to present SIPG as “the Chinese port, owned by the Chinese government, a government that is part of the axis of evil with Russia and Iran and an open supporter of Hamas, which instructed its national shipping company, COSCO, not to visit Israel.”

In another case, in March of that year, it was reported that the United States suspected that cranes manufactured by the Chinese company ZPMC could transmit operational data to Beijing via an internet connection between the cranes and the technical support center in Shanghai. These reports raised questions about the safety of the cranes installed in Israel at the Bay Port, South Port, and Ashdod Port. The chairman of Ashdod Port was quick to criticize the “Chinese oversupply” worldwide and claimed that at Ashdod Port, the Chinese electronic systems had been replaced with European ones, implying that this step had not been taken in other ports.

The management of (the “old”) Haifa Port, which is trying to restrict the mandate granted to the Bay Port and is being forced to compete with it, has also criticized the “Chinese port.” In July 2024, the chairman of the Haifa Port Company, operated by the Israeli–Indian Adani-Gadot Group, sent a letter to the Ministries of Finance, Transportation, Foreign Affairs, Economy, and other key players in the industry. In the letter, he complained about the exceptional approval granted to the Bay Port to use two additional docks beyond those permitted in the original agreement. This approval, given to the Bay Port in April 2022 for a period of two years and limited to general cargo operations only, aimed to address the problem of long queues of general cargo ships waiting to enter Israeli ports at that time. After Transportation Minister Miri Regev delayed action for several months, a draft framework for regulating the ports was published in August 2024. This framework allows the continued use of the two docks for general cargo operations by the Bay Port, a move that, according to the chairman of Haifa Port, would harm fair competition between the ports. Whether these claims are justified or not, the chairman of Haifa Port also chose to inject his remarks with inter-power undertones, emphasizing that it is a “Chinese port” and asserting that “the Indians feel deceived.” It turned out that Transportation Minister Regev also adopted this narrative; one of the justifications she presented in her request to the Knesset Travel Committee for approval to travel to India was that “the issue of Docks 7 and 8 at the Bay Port, currently operated by the Chinese, has recently become a significant diplomatic issue.”

The Bay Port’s Performance

The World Bank’s Container Port Performance Index (CPPI) annually ranks container ports worldwide based on the total dwelling time of ships at the port. The Index considers all ports in the Haifa port area as one port unit, as it does all ports in the Ashdod port area. According to the 2022 ranking, Haifa’s ports rose to 56th place from 196th in 2021 while Ashdod’s ports remained stable in 297th place. In 2023, both complexes dropped in ranking, likely due to the war in Gaza.

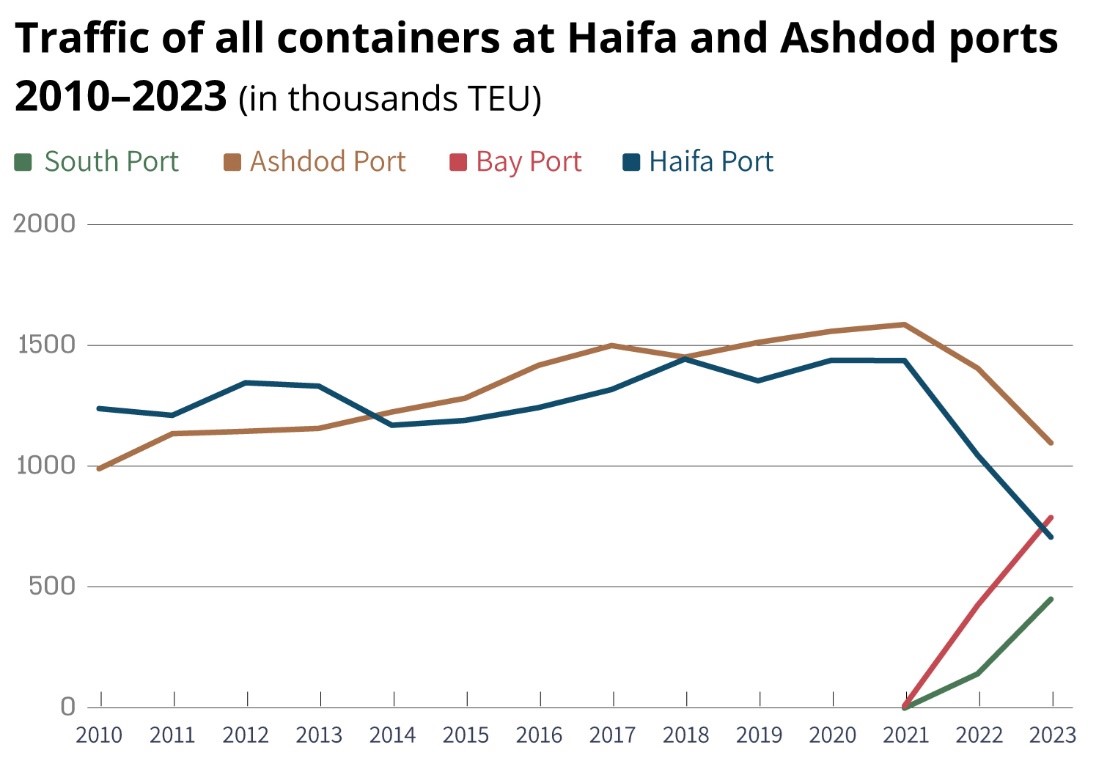

A significant part of the improved performance of Haifa’s ports can be attributed to the Bay Port, which surpassed the number of containers (in TEU)[1] unloaded and loaded at the older Haifa Port. In 2023, the Bay Port handled 830,000 containers compared to approximately 700,000 containers at the older Haifa Port. The South Port also sparked some competition with the adjacent older Ashdod Port, albeit to a lesser extent, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Source: Based on data from the Shipping and Ports Authority.

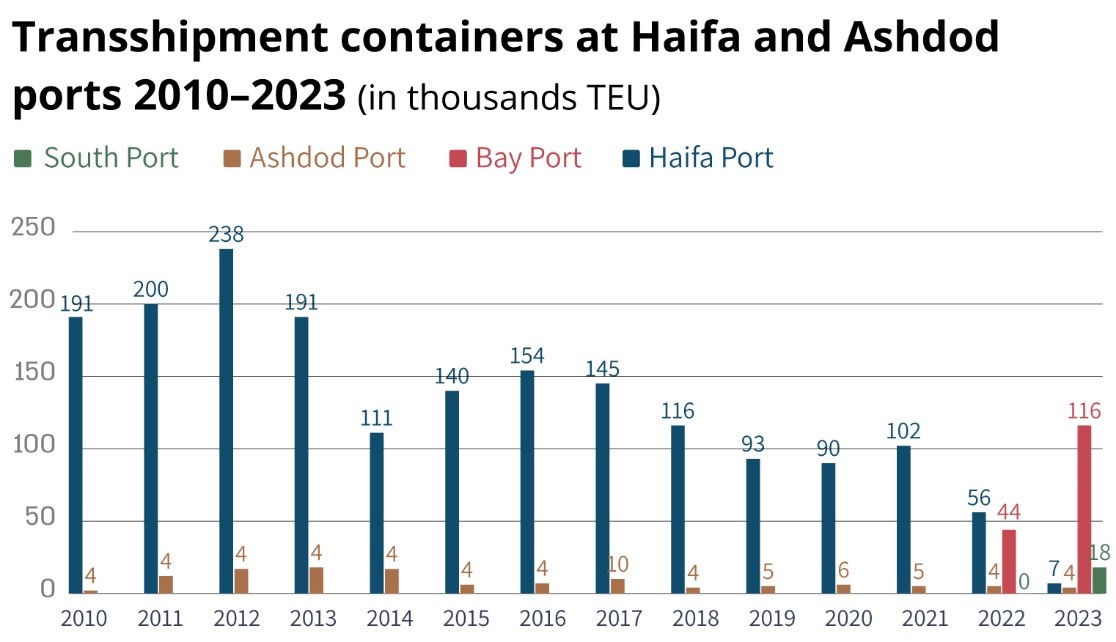

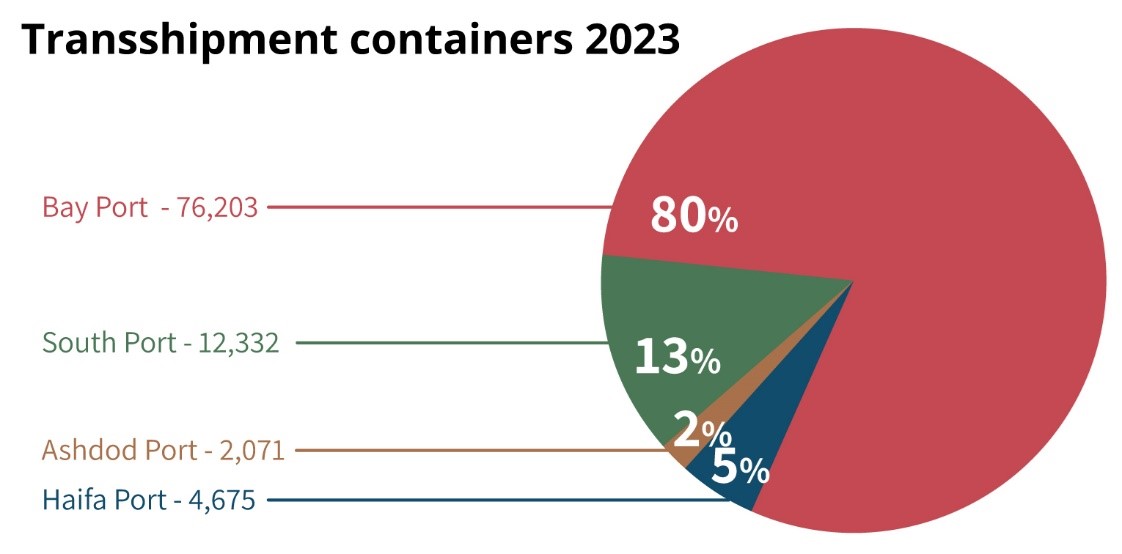

This competition should also consider the Bay Port’s success in transforming Israel into a hub for goods. According to Israel’s 2023 Statistical Yearbook for Shipping and Ports, the Bay Port experienced a significant increase in the number of transshipment containers it handled. [2] The South Port also saw a smaller increase in this area.

Figure 2.

Source: Administration of Shipping and Ports, The Statistical Yearbook for Shipping and Ports 2023.

Figure 3.

Source: Administration of Shipping and Ports, The Statistical Yearbook for Shipping and Ports 2023.

After three years of steady growth in the Bay Port’s operations, the war in Gaza and the economic slowdown in Israel significantly slowed down the cargo movement at Israel’s ports. The port’s goals of becoming a hub for goods in the Mediterranean suffered a major setback due to the war, and strained relations, particularly with Turkey, led to a significant decline in transshipment activities. The port’s management has reported a 40% decrease in activity since October 2023, mainly due to the drop in transshipment operations. Meanwhile, the Bay Port is preparing for the post-crisis period, hoping to regain the permit for additional activities at berths 7 and 8 to unload general cargo and is attempting to collaborate with the Aqaba Port in Jordan. In the future, it may also handle vehicle shipments, along with the Ashdod and Haifa ports, instead of the currently inactive Eilat Port.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In its three years of operation, the Bay Port has met commercial expectations, reaching a peak of 454,000 TEU in the first half of 2023. Had the war in Gaza not erupted, the port would have likely reached the goal of one million TEU annually, and it is expected to return to this level again once the economy resumes regular activity following the war. In addition to being an important deep-water port, the port also competes with other port operators in Israel, particularly Haifa Port Company, the operator of the “Old Haifa Port,” which it challenges to improve efficiency and excellence. However, it faces criticism from its counterparts at neighboring Haifa Port, which has seen a decline in results (mainly due to the war), since its privatization at the end of December 2022 and acquisition by the Adani-Gadot Group, leading to conflicts among its owners. The competition between the Bay Port, the two Ashdod ports, and Haifa Port is expected to continue and even intensify after the war, as the total port capacity (5 million TEU) exceeds the current container activity in Israel (3 million TEU), allowing for healthy competition.

Regarding the criticisms that the port is “Chinese” and therefore dangerous for various reasons, it is important to note that it is an Israeli corporation, albeit owned by a Chinese entity (similar to the Tnuva food manufacturing company, for example). Like all port corporations in Israel, the Bay Port operates under a license from the Israel Ports Company—a government body—and is subject to regulation and oversight by the Shipping and Ports Authority. The Authority authorized the port’s operation in September 2021, and the port is also supervised by Israel’s security agencies, as specified in its operating license. Most concerns about the port have been disproven over the years, without any evidence to support the majority of claims. Instead of the fears materializing about the port’s Chinese ownership, the operation of the Bay Port has brought numerous benefits, including increased competition among Israel’s ports and lowering the cost of living.

The operation of critical infrastructure by an Israeli company owned by a foreign power cannot be separated from that power’s attitude toward Israel. Since October 7, the Chinese government has not condemned Hamas or its actions and has even given the organization legitimacy by hosting its representatives in Beijing for “reconciliation talks.” China has also initiated discussions at the UN against Israel and has condemned its actions. As a result, a negative public sentiment has emerged against China in Israel, with 57.1% of all Israeli citizens (61.4% of the Jewish sector only) viewing China as an unfriendly and even a hostile country, according to an INSS survey. This negative sentiment is likely shared by Israel’s decision-makers as well.

However, it is important to differentiate between the Chinese government and its business companies. Despite some connection with the government, these companies operate with significant freedom and independence, as demonstrated by the Bay Port during the war. Although the participation of Chinese companies in infrastructure tenders in Israel has recently declined, Chinese companies still have significant advantages in infrastructure development. Therefore, in future tenders, Israel should not prohibit the participation of Chinese companies outright but should carefully consider their candidacy, taking into account economic, security, and diplomatic aspects. If the economic benefits are substantial and security and diplomatic considerations allow, there is no reason to prevent the participation of Chinese companies, and it may even be advisable to encourage them. At the same time, in areas where exposure needs to be limited, such as for national security reasons, the specific case should be referred to the “Advisory Committee for the Examination of National Security Aspects in Foreign Investments.” Overall, it is important to remember that Israel’s relations with China are of great importance, particularly in the economic field, but not exclusively. Maintaining cooperation with a clear perspective is in Israel’s interest and is the key to a successful and secure relationship.

[1] TEU (Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit) is the standard measurement unit for a 20-foot-long container.

[2] Transshipment refers to the unloading of containers from large ships and transferring them to smaller ships that head to other destinations. This process allows the port to benefit as a central hub in the supply chain.