Publications

INSS Insight No. 1868, June 23, 2024

In the ongoing conflict between Iran and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and following a resolution condemning Iran’s lack of cooperation with the agency, Tehran announced an increase in the number of centrifuges enriching uranium at the Fordow and Natanz sites, effectively declaring its intention to increase its stockpile of enriched uranium. With the current quantities, Iran could, within a month of making a decision, begin enriching to military levels and produce enough enriched material for eight nuclear devices. This raises significant questions about Iran’s nuclear strategy, particularly the possibility that it is now operating under a different logic than in the past and is practically striving to reach a point in the not-too-distant future where it could also advance steps needed to acquire nuclear weapons. A comprehensive Israeli and international effort is required to prevent this development. For Israel to advance this urgent strategic goal, it needs to strive to end the fighting in Gaza, calm the northern front and other arenas, and rebuild its international standing. These actions, coordinated with the Biden administration and even as an achievement for it, could serve as an important platform for mobilizing the administration’s resources on the Iranian issue.

The IAEA Board of Governors concluded its quarterly meeting (June 5–6) by adopting a resolution, for the first time in about a year and a half, expressing growing concern over Iran’s lack of cooperation with the agency’s oversight and demanding that it meet its obligations. This resolution, submitted by the three European countries signatories to the nuclear agreement (JCPOA)—France, the United Kingdom, and Germany—faced opposition in the days leading up to the meeting from the US administration, which preferred to avoid increasing tensions with Iran but ultimately had to support the resolution. Russia and China, which blamed Washington’s withdrawal from the agreement for all the problems, opposed the resolution, and 12 countries, including South Africa, India, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, and Turkey, abstained. In response, Iran announced an increase in the number of centrifuges enriching uranium at the Fordow and Natanz sites, meaning an increase in the amount of enriched uranium it will accumulate. In response, the Europeans and Americans emphasized that they would be prepared to take additional steps if Iran continues to violate its obligations to the IAEA.

Before the meeting, as is customary, the Agency submitted a technical report to the members of the Board of Governors on May 27. The report emphasizes, among other things, Iran’s non-compliance with the oversight requirements according to the NPT treaty to which it is a signatory. The director general of the Agency highlighted that Iran has the technical capabilities to produce nuclear weapons. In this context, he detailed statements from Iranian officials regarding changes in Iran’s nuclear doctrine as a reason for growing concern. The report condemns, as in previous reports, Iran’s decision to deny entry visas to several specialized inspectors and its refusal to update the Agency at the initial stages of constructing new nuclear facilities, continuing to adhere to a narrow interpretation of its obligations, only for advanced stages, when nuclear material is introduced into the facility. These issues were discussed during the director general’s visit to Tehran in early May, but according to him, he did not receive proper cooperation from Iran.

Regarding the quantities of enriched uranium in Iran’s possession and its ability to enrich them to the high level required for producing a nuclear bomb, according to the analysis of a leading American institute in the field, the Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), within a month of deciding to begin enriching to military levels, Iran could produce enough enriched material for eight nuclear devices, within two months for ten devices, and within three months for twelve devices. The main implication is that Iran already has the capability to produce the first quantity of 25 kg of enriched material to a military level within about one week. Such an action might not allow the IAEA to detect it quickly if Iran delays the inspectors’ access.

An expression of concern can be found in the remarks of the director general of the Agency before the Board of Governors on June 2, during which he clarified that Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium, including uranium enriched up to 60%, continues to grow. Iran has restricted the IAEA’s oversight, resulting in the disruption of the Agency’s information on centrifuge production, the number of stored centrifuges, their rotors and blowers, heavy water, and uranium ore concentrate. Consequently, according to him, the IAEA has been unable to conduct the required oversight of Iran’s nuclear program for over three years.

Understanding the current state of Iran’s nuclear program, as of May 2024, repeatedly raises the question of whether we are in a known and familiar process, of an unfolding event that will at some point turn into the severe scenario of a nuclear bomb in the hands of the Iranian regime. If this is indeed the scenario, what should the international community and Israel do to prevent it, and is it possible at this advanced stage of the program to prevent nuclear armament?

On the surface, the American administration, led by President Biden, continues to hold the declared position of preventing Iran from obtaining military nuclear capabilities. However, given the administration’s policy to avoid escalating the confrontation with Iran, at least until the elections in November 2024 due to concerns about Tehran’s reaction, several troubling questions arise:

- Are we in a period—the race for the US presidency—in which the Iranians might exploit taking another step toward preparing the ground for a future decision to acquire military nuclear capability? This is due to their understanding of the sensitivity the American administration attributes to any additional crisis, on top of the existing ones, affecting the election campaign.

- Does the Iranian regime now, following its lessons from the Swords of Iron war, place greater importance on achieving the ultimate deterrent capability in the form of a nuclear weapon?

- What are Iran’s lessons from the mutual strikes between it and Israel regarding its ability to confront Israel in the scenario of a full-scale war or an Israeli strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities?

- How does the succession issue for the day after Ali Khamenei affect the supreme leader’s considerations on progressing toward nuclear weapons, especially in light of the death of President Raisi (a potential candidate)? Does he still adhere to his long-standing position of careful and not necessarily rapid advancement toward only a nuclear threshold state?

Recently, Iranian officials have again raised the possibility of political negotiations to reach understandings with the international arena on its nuclear program. This topic even came up, apparently, on the sidelines of indirect talks that the White House’s Middle East coordinator, Brett McGurk, held with Iran in Oman. In the background is Tehran’s desire to “pass peacefully” until October 2025, when, according to UN Security Council Resolution 2231, the Iranian nuclear file is supposed to close. Until then, any of the three European countries (the E3) can use the snapback mechanism to reimpose all UN Security Council resolutions against Iran, without a veto from Russia or China. Seyed Hossein Mousavian, who was Iran’s ambassador to Germany in the 1990s and is now a lecturer at Princeton and who represents Iran’s positions in his articles, clarified that in such a scenario, Iran would abandon the Non-Proliferation Treaty and thereby cease to be committed to it as a non-nuclear state. Mousavian states, in rather threatening language, that the United States and the European Union have a 15-month window to choose between two options: “Iran as a nuclear state like North Korea, or Iran as a nuclear threshold state like Japan.”

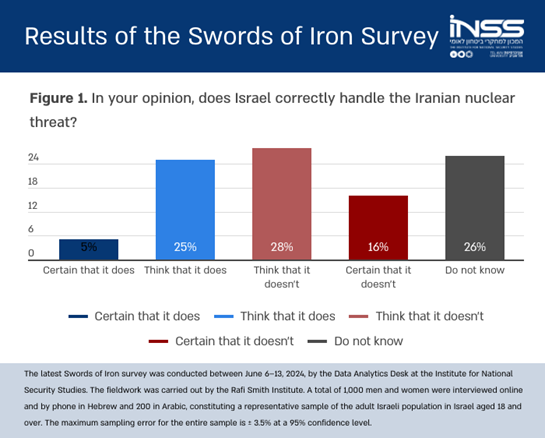

The severe strategic implications of achieving military nuclear capability by a radical religious regime like Tehran’s require a comprehensive, systemic, and international effort to prevent this development. The extensive resources currently devoted by Israel’s political and military leadership to the prolonged and difficult war in the south and north have pushed the issue of Iran’s advancing capabilities to the sidelines, leaving it without the necessary attention. A recent survey conducted by INSS among the Israeli public indicates that the majority of respondents—44%—believe that Israel is not handling the Iranian nuclear threat correctly (see Figure 1).

In a clear strategic assessment, Israel is fighting tactical wars, partially out of necessity, in which it has some achievements. However, it risks losing the more important strategic battle: preventing a nuclear Iran. This severe development, if it occurs, threatens Israel’s national security more gravely than it does any other international or regional actor. Therefore, without Israeli mobilization to spur the international community into action, Iran will continue to progress until it feels secure enough to take the next step toward acquiring a nuclear bomb. To advance this urgent strategic goal, Israel must aim to end the fighting in Gaza, stabilize the north and other fronts, and rebuild its international standing in order to focus attention on the dangerous and concerning progress of Iran’s nuclear program. Such moves, in coordination with the Biden administration and considered as an achievement by it, can serve as an important platform for rallying the administration’s resources on the Iranian issue.