Publications

Special Publication, May 26, 2020

The IDF withdrawal from Lebanon 20 years ago and the renewed deployment along the UN-recognized international border was a unilateral move by Israel, welcomed by the international community. By contrast, the application of Israeli sovereignty over territory in the West Bank, also a unilateral move, will be the annexation of disputed territory between Israel and the Palestinians, and there is a broad consensus among leading international elements of its illegality. Three critical parameters of Israel’s exit from Lebanon may shed light on the implications of annexation in the West Bank: game change; context; and unilateralism. Annexation without a political settlement with the Palestinians will be a game changer, since it will disrupt the situation and change the rules of the game in the conflict arena. While over time the balance of the consequences of leaving Lebanon has come to tilt toward the positive, the atmosphere in Israel and among the Palestinians, along with past experience, demonstrates that it is hard to expect any positive outcome or strategic advantage for Israel from annexation. In terms of context, annexation is seen by some as a historic opportunity due to American support as well as the regional and international focus on other burning issues. But these circumstances could prove marginal when the long term problematic significance of the move becomes clearer, because it will lead to the entanglement of hostile populations and will threaten the realization of the vision of Israel as a Jewish, democratic, secure, and moral state. Finally, the unilateral nature of the withdrawal from Lebanon, which was grounded in international legitimacy and deployment south of the Blue Line, did not slam the door on any future political process. By contrast, unilateral Israeli annexation in the West Bank will thwart any future prospects of a negotiated agreement between Israel and the Palestinians.

On May 24, 2000 the IDF left the security zone in southern Lebanon, after an 18-year stay that exacted a heavy human toll, mainly in the fight against Hezbollah. The organization, which originated in the Shiite community in Lebanon, was established during the First Lebanon War (1982) by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, with the encouragement and assistance of Syria. Upon its withdrawal, Israel redeployed along the international border between Israel and Lebanon recognized by the UN (the Blue Line), and not to a line whose security advantage derived from dominating territory. Subsequently, then-UN Secretary General Kofi Annan confirmed that Israel had left all Lebanese territory.

The military rationale underlying the security zone was to prevent Hezbollah forces from accessing the border, block terrorist cells trying to enter Israel, and deflect fire away from Israeli territory toward the SLA units and IDF outposts. During those years Israel was prepared to pay a heavy price in the lives of soldiers to secure a known degree of normal life for the residents of northern Israel. Lebanon became an alternative battlefield between Israel and Syria, and while the IDF was in Lebanon, the Israeli-Syrian border on the Golan Heights remained calm. However, the ethos of initiative and offensive on which the IDF was educated was undermined: it became clear that deterring terrorists and operating in the midst of a civilian population was far more challenging and complex than deterring regular military forces. Instead of maintaining the initiative and the offensive, IDF forces had to be protected and fortified, and most of their activity was response-based.

The narrative that has taken shape in the years since the withdrawal from Lebanon – and in the eyes of many is also supported by developments in Gaza following the disengagement in 2005 – is one of retreat due to lack of endurance. The determination of Prime Minister Ehud Barak to keep his election promise of withdrawal (which was announced after the commander of the Lebanon Liaison Unit [LLU] Brig. Gen. Erez Gerstein was killed by an IED in Lebanon) was interpreted as the outcome of weariness in Israeli society and political circles due to the large number of casualties suffered by forces in the security zone. In the background were the Four Mothers movement and the growing protests calling for withdrawal, while the effects of difficult incidents were still palpable, above all the helicopter crash in 1997, which caused the deaths of 73 IDF soldiers on their way to the security zone. Indeed, public opinion polls at that time showed that some 70 percent of respondents backed the withdrawal from Lebanon, while only 20 percent opposed it.

However, contrary to the prevailing narrative, the context of the withdrawal was the talks with Syria underway as part of a political process between Israel and Arab states and the Palestinians, a continuation of sorts of the Madrid Conference (October 1991). At that time, Syria had control of Lebanon and acted to prevent the possibility of a separate Israel-Lebanon agreement. Later, Barak said that Israel did not leave Lebanon when he was Chief of Staff because Yitzhak Rabin wanted to do so through negotiations with the Syrians, since he would not consider leaving without an agreement. Both Shimon Peres and Benjamin Netanyahu – Prime Ministers who served after Rabin – linked any settlement in Lebanon, including the withdrawal of IDF forces from Lebanese territory, to an overall arrangement with Syria. But the security zone lost its importance as a bargaining chip in the talks with Syria following the failure of the Geneva Summit between US President Bill Clinton and Syrian President Hafez al-Assad in March 2000. Moreover, there were growing doubts over the security benefit of remaining in southern Lebanon: the IDF had no satisfactory response to Hezbollah tactics that did not incur a high human cost; the security zone itself was in a shambles; and instead of protecting residents of the north, the area became a military and political burden.

A game changer is the move to change a static situation or negative strategic reality versus an enemy, and as such, to create a new situation. However, it is not always possible to assess the future implications. When the idea of a unilateral withdrawal from Lebanon was presented, it was already clear that this was a game changer. The withdrawal was intended to change a long term, problematic strategic reality, because it was impossible to promote a settlement with Syria and Lebanon and deny Hezbollah a reason to continue attacking IDF troops in order to change the rules of the game in the north. Clearly, the withdrawal from Lebanon would necessarily incur very serious strategic consequences, both negative and positive, that would be the outcome of local and regional circumstances, and not all of them could be predicted at the time of the decision or its implementation.

The negative outcomes: (1) The Hezbollah challenge became more severe. Its forces were deployed along the border, with the ability to fire directly at towns and villages in northern Israel. It acquired more and considerably better weapons. In addition, it found/improvised new grounds for the struggle against Israel (the village of Ghajar, Shab’a farms, as well as the Palestinian issue), and built up a strong image as fighting resistance and the defender of Lebanese interests. As the de facto ruler of southern Lebanon, over the years Hezbollah made a number of attempts to kidnap IDF soldiers as bargaining chips – two attempts were successful, and the second was the trigger for the Second Lebanon War (summer 2006). (2) The declaration by Prime Minister Ehud Barak that Israel would react rapidly, forcefully, and with determination to terror attacks from Lebanon did not pass the test of reality: Israel did not respond to the kidnapping of three soldiers in the Mt. Dov sector in October 2000, which coincided with the outbreak of the second Palestinian intifada. Israel’s responses to terror incidents were relatively mild, and Hezbollah continued to dictate the rules until the kidnapping incident of July 2006. In effect, only the Second Lebanon War drove Hezbollah forces away from the border, although not entirely, when the Lebanese Army was deployed along the border alongside reinforced UN peacekeeping force – UNIFIL. However, Hezbollah’s efforts to build its military strength were not halted by the Second Lebanon War, and even increased. (3) An opening was created for Iranian involvement and influence in Lebanon, including the deployment of Iranian intelligence units close to the Israeli border. (4) Israel left southern Lebanon in haste following the rapid collapse of the South Lebanon Army (SLA) and the abandonment of its outposts (the SLA was a local militia established in 1976 on the basis of interests that were shared by Israel and the residents of southern Lebanon following the Lebanese civil war), probably because of rumors of an imminent Israeli withdrawal. Along the Lebanese security zone there were over 30 SLA positions and 13 IDF positions. The SLA was supposed to continue maintaining security in the border area even after the withdrawal of the IDF, and to try and prevent Hezbollah taking control. These hopes, which in any case had no foundation, were quickly dashed, and 6800 SLA soldiers and their families fled to Israel. (5) Pictures of the hasty retreat, with Israeli military equipment abandoned on Lebanese soil, eroded Israel’s deterrent image as a power that could not be defeated militarily. Soon thereafter, Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah began to market the image of Israeli society as a “spider web” – weak, hollow, and tired. (6) It was claimed that withdrawal encouraged the outbreak of the second intifada in the West Bank and Gaza Strip a few months later. However, this claim ignores the frustration that had built up among the Palestinian populations over the years in which implementation of the interim agreements stalled, Hamas became a serious to the Palestinian Authority, and efforts failed to promote an agreement between Israel and the Palestinians in the Camp David talks held that summer under American auspices.

As for the positive outcomes: (1) Israel demanded and received international legitimacy for the withdrawal, based on Security Council Resolution 425 (from 1978 after Operation Litani), with strict observation of IDF deployment south of the international border. The action upholding the international norm led to Security Council Resolution 1559 (September 2004), which called for respect for Lebanese independence and sovereignty, and an end to the Syrian military presence and the dismantlement of the militias in Lebanon, above all Hezbollah (a clause that was not observed). In Israel there was also an expectation that following Resolution 425, the Lebanese government would be required to exercise its sovereignty and deploy the Lebanese Army along the border with Israel, but this occurred only happened after the Second Lebanon War. (2) The IDF withdrawal deprived Syria of legitimacy for the presence of its troops in Lebanon, and led to Security Council Resolution 1559. Together with other events in Lebanon, including the murder of Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri and the overthrow of the government in the Cedar Revolution, there was growing local and international pressure on Syria that led to the removal of its forces from the country. (3) Since the withdrawal from Lebanon, and particularly since the Second Lebanon War, there has been a sharp decline in the number of incidents along the border and a long period of calm. (4) Together with greater military strength, and apparently to some extent because of it, Hezbollah has been accepted as a legitimate element in the political and social systems in Lebanon. Its actions are influenced by a broader spectrum of political considerations than would apply to a purely terrorist organization. These considerations dictate a fairly pragmatic and restrained policy to avoid tipping over the edge into escalating the conflict with Israel.

Between Withdrawal and Annexation

The withdrawal from Lebanon led to renewed deployment of the IDF/Israel along a recognized international border. In contrast, the application of Israeli sovereignty over territory in the West Bank would involve the annexation of areas under dispute between Israel and the Palestinians, and where there is broad consensus among leading international entities about the illegality of the move. Nonetheless, an analysis of the withdrawal in 2000 leads highlights three main parameters that can help to examine the implications of unilateral annexation in the West Bank: game change, context, and unilateralism.

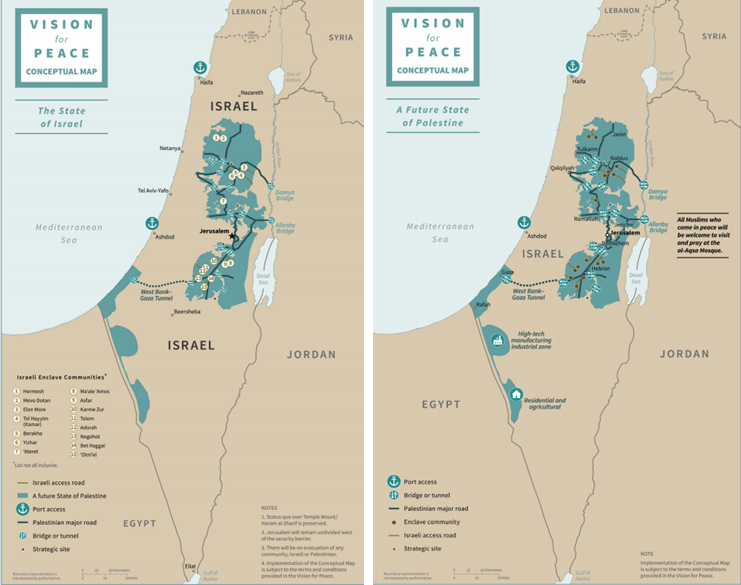

Game Change: There is no doubt that the annexation of West Bank territory without a political agreement with the Palestinians is a game changer of major magnitude. After annexation – irrespective of its extent, and irrespective of US administration support – all the rules of the game between Israel and the Palestinians will change. While on balance the consequences of the withdrawal from Lebanon have come to be seen as tending toward the positive, close familiarity with the Israeli-Palestinian arena and past experience – both conflict and attempts at rapprochement – indicate that it is hard to expect positive consequences and strategic advantages for Israel from annexation. Not only will such a move not promote an Israeli-Palestinian arrangement; it will even take the relationship backwards, back to the days prior to the creation of a basis for regular dialogue. This basis is still valid, despite the political stalemate, particularly with respect to security and economic cooperation between the parties – even if the discourse about Israeli annexation has heightened the threats from the Palestinian Authority, including President Mahmoud Abbas, to cancel it. The PA, although it controls only part of the Palestinian territories – with the Gaza Strip under Hamas control – is Israel’s official partner for any future negotiations. Annexation of the West Bank, while grounding any possibility of promoting an Israeli-Palestinian settlement, will also undermine the legal-political basis for the PA’s very existence, and could accelerate its dismantlement or collapse. If the PA fails to survive the collateral effects of the annexation, including widespread popular unrest, Israel will find itself responsible for the basic welfare and more of some 2.7 million Palestinians in the territories. This coincides with the growing popular support in the territories for the idea of one state, given the disappointment with the two-state vision. Joining the economic burden is the problematic development for Israel’s democratic and demographic character. Moreover, the international community will not recognize Israeli sovereignty over the annexed territory, and there may even be growing support for Palestinian rights to self determination and a state within the June 4, 1967 lines, and their efforts to challenge Israel in international forums. The only benefit that would likely derive from annexation is largely emotional-ideological – realizing the right of the State of Israel to parts of the homeland. Yet the realization of this goal must be weighed against the security needs of the people living in the region, which will increase if they remain in a volatile area full of hatred.

Context: Annexation is cast as possibly a unique opportunity, created by specific circumstances: President Donald Trump, a friend of Israel, is in the White House; the world is preoccupied with the Covid-19 pandemic; and interest in the Palestinian caused has dropped in international circles. In other words, the context for annexation is an opportunity limited to a specific window of time. However, if the intention to annex is examined in the broader strategic context – the future of the political process between Israel and the Palestinians, the ability to achieve a two-state solution and/or separate from the Palestinians, politically, geographically, and demographically – the opportunity, whether in the context of mixing people or separating populations, lacks significance, and in fact is potentially disastrous.

Unilateralism: Critics of the withdrawal from Lebanon and the disengagement from the Gaza Strip as unacceptable unilateral moves may well support unilateral annexation in the West Bank, based on the claim that this is not a withdrawal but rather “the application of sovereignty” – its complete opposite. Nevertheless, positive aspects of the withdrawal from Lebanon derived from the fact that it was based in territorial terms on Security Council Resolution 425, that is, redeployment south of the Blue Line, and not on a breach of international law and resolutions. Moreover, the retreat from Lebanon did not close the door to any future political process. An agreement that gains international legitimacy should be a source of stability and security, even if not immediately. By contrast, a unilateral move in the West Bank will slam the door in the face of any progress toward a negotiated agreement, while diminishing the possibility of promoting contacts and cooperation with Arab states. In fact, the positive avoidance of any unilateral move, particularly if accompanied by a call to the Palestinians to return to the negotiating table, could promote significant Israeli interests in the Middle East and the world.

One final comment relating to the withdrawal from Lebanon concerns the abandonment and betrayal of the SLA. In this context, Ehud Barak said that “complicated situations create painful dilemmas; there are no magic solutions.” Indeed, there are no magic solutions, but perhaps it would have been possible to act differently toward the SLA after 22 years of cooperation. Today, the security apparatuses of the Palestinian Authority are cooperating with the IDF in a regular, methodical way, and are credited with stopping many attempted terrorist acts. They are responsible for all aspects of law and order in the PA territory. Have the supporters of the application of Israeli sovereignty in the West Bank examined the possibility that the Palestinian security services will feel betrayed, their rank and file will exhibit hostility toward Israel, and that they will break up and “only” stop functioning? What are the security implications for Israel in that case? How, if at all, is it possible to establish, stabilize, and increase Israel’s security in a reality where mutually hostile populations are merged?