Publications

INSS Insight No. 1980, May 14, 2025

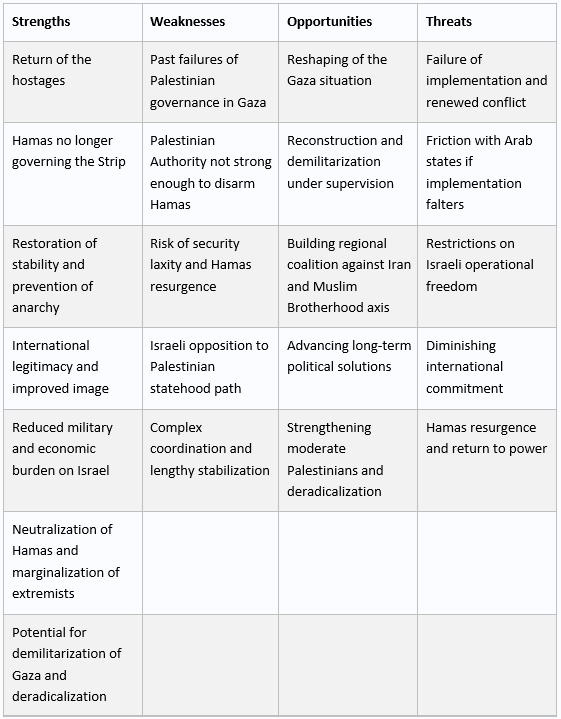

The Israeli government has authorized the IDF to finalize preparations for “Gideon’s Chariots”—a plan to conquer the Gaza Strip and defeat Hamas, concentrate the population of the Strip in its southern region, and encourage emigration from it. The execution of this plan would come at a heavy cost: the killing of hostages and the loss of information regarding their whereabouts; additional casualties within the IDF; a decreasing likelihood of achieving normalization with Saudi Arabia; a deepening of internal divisions in Israel due to the expected military toll and the political tensions that would escalate as a result; heavy economic costs; increased exposure to legal and diplomatic risks; and the moral consequences of the IDF’s anticipated actions. All this comes at a time when it is unclear whether the State of Israel currently possesses the diplomatic, military, and societal stamina necessary to achieve the objectives of the plan. In contrast stands the Egyptian proposal—backed by the Arab League—for a ceasefire, the release of hostages, and the establishment of a Palestinian technocratic administration in Gaza under regional and international auspices. While the Egyptian alternative entails a renunciation of the full military defeat of Hamas, its implementation would advance the release of hostages, promote security stabilization and civilian reconstruction of the Strip, increase the chances of expanding the circle of the Abraham Accords and achieving normalization with Saudi Arabia, and help address the socio-political crisis within Israel.

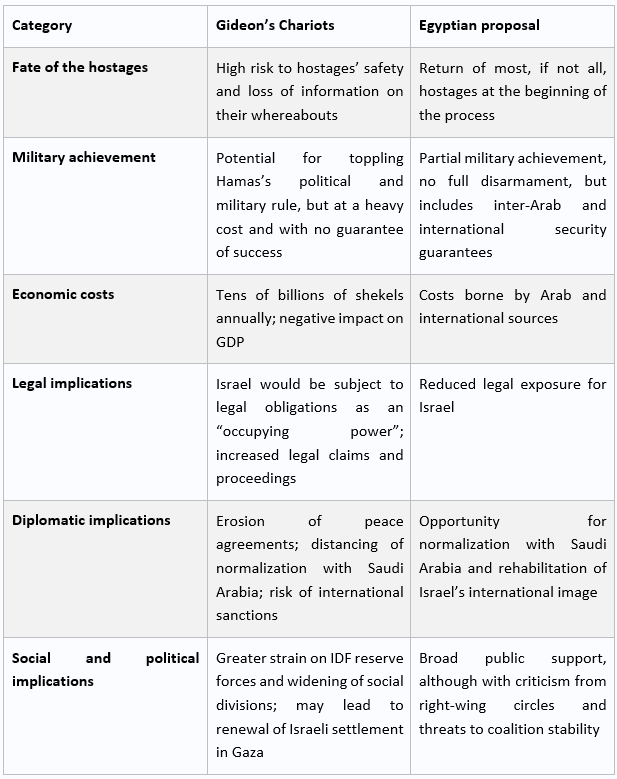

On May 5, the Israeli government approved the plan of “Gideon’s Chariots,” presented by the IDF, for the open-ended conquest of the Gaza Strip as the final and decisive stage of the war. The declared objectives of the plan are the military and governmental destruction of Hamas as the top priority and the return of the hostages as a secondary goal. For the first time, this plan establishes a clear hierarchy in the Israeli leadership’s priorities regarding the two original objectives of the war, as declared since October 2023.

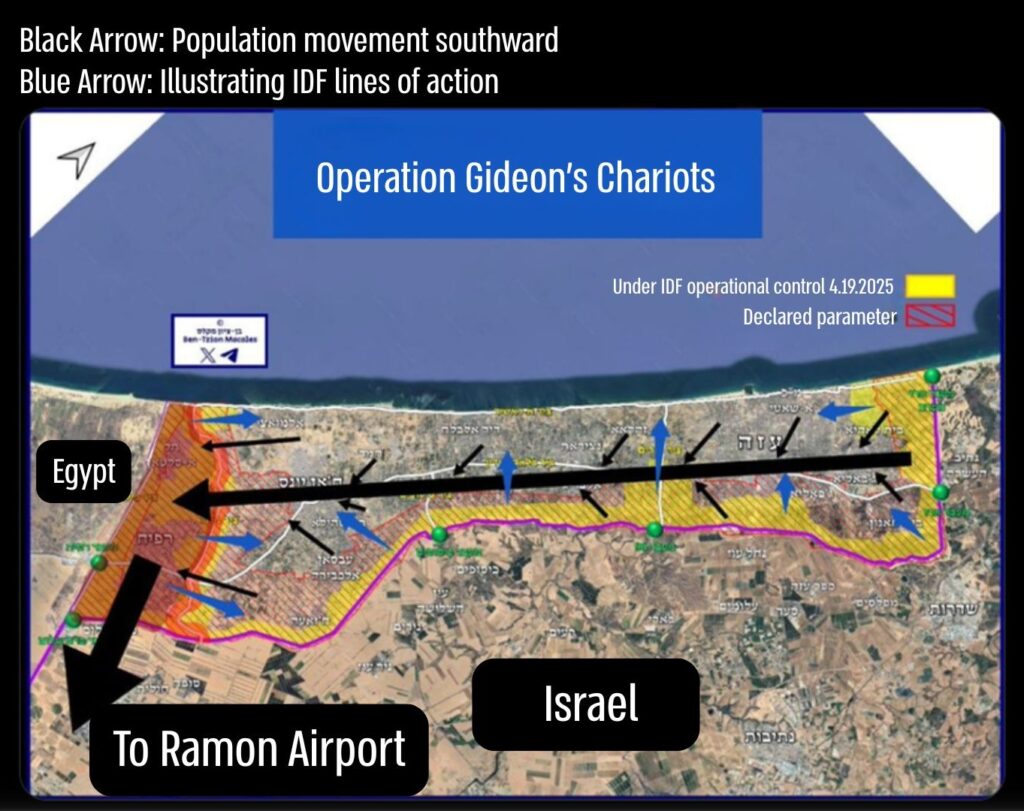

Outline of the Plan. The core of the operational plan is based on the evacuation of the entire population of the Gaza Strip—just under two million people—to the Rafah area, within the zone between the Philadelphi Corridor and the Morag Route (see Figure 1). Concentrating the population in this zone is intended to allow the IDF to pursue two goals: conquering the remaining territory and clearing it of Hamas operatives and infrastructure, unhindered by the constraints posed by the presence of civilians; and encouraging the emigration of Palestinians from the Gaza Strip.

Distribution of Humanitarian Aid. Israel plans to establish a “sterile zone” under its control, in which aid will be distributed directly to the population by foreign companies and under Israeli security, thereby neutralizing Hamas’s involvement in the process. This step is intended to reduce Hamas’s ability to exploit humanitarian aid as a means of influencing the population and as a resource base for recruiting and operating terrorist cells.

Figure 1. Operation “Gideon’s Chariots”

Note. Adapted from @BenTzionMacales, X, May 5, 2025, https://x.com/BenTzionMacales/status/1919479779088376007

According to statements by Israeli officials, the “Gideon’s Chariots” plan will be implemented after President Trump’s visit to the Middle East, which starts on May 16, unless agreements are reached with Hamas by then regarding a hostage release deal under terms acceptable to Israel. The preparations for the operation and the threat of its execution are meant to incentivize Hamas to accept the outline for a hostage deal proposed by President Trump’s envoy, Steve Witkoff, which centers on a partial deal under which only some of the hostages would be released, while Israel would retain the ability to resume fighting. As of now, the negotiations are at a dead end due to Hamas’s insistence on a full deal involving the return of all hostages and an end to the war, versus Israel’s adherence to the Witkoff outline.

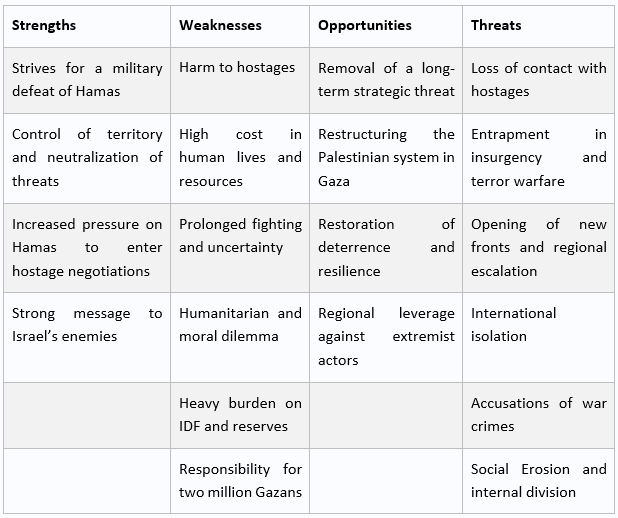

Competing with the “Gideon’s Chariots” plan for the conquest of the Gaza Strip is a strategic alternative based on the Egyptian proposal, which was adopted by the Arab League and rejected outright by the Israeli government. Its main points are the release of all hostages and a halt to the war in the first stage; the establishment of a Palestinian technocratic administration in place of Hamas rule (which has already agreed to relinquish civilian control of the Gaza Strip), operating under the auspices of the Palestinian Authority and with the assistance of an Arab and international auspices; the deployment of Palestinian and Arab security forces in the area; and the initiation of a reconstruction plan for the Strip funded by Arab and international sources.

In Israel’s public discourse, there is no organized and systematic discussion—neither by the leadership and the political system as a whole nor by the media—about the implications of the “Gideon’s Chariots” plan and its consequences, or about the competing alternative. Below is an analysis of the risks and opportunities inherent in the plan, both in itself and in comparison to the Egyptian proposal.

The Fate of the Hostages

Operation “Gideon’s Chariots” is expected to result in the killing of hostages and the loss of information about their whereabouts, including the deceased hostages. This could occur due to IDF strikes and acts of revenge by Hamas, or as a result of the captors fleeing the combat zones and leaving the hostages behind.

According to the Egyptian proposal, all hostages would be returned in the first stage of the deal. In practice, Hamas may delay or prevent the release of all hostages under various pretexts in order to retain some as a “guarantee.” Nevertheless, even in this case, it is reasonable to assume that at least most of the living hostages would be returned. Also, in the case Hamas refrain from releasing all the hostages, Israel would have both internal and external legitimacy to resume fighting, with relatively fewer concerns about harming hostages during its military operations.

Expected Military Achievement

The plan for “Gideon’s Chariots” includes a broad IDF incursion into the Gaza Strip and a prolonged conquest of large areas, aimed at collapsing Hamas’s rule and dismantling its military wing—but not eliminating terror cells that will continue to operate against Israeli forces. In the optimal scenario, Hamas would become a secondary player, and Israel would be able to implement long-term strategies in the Gaza Strip—continued occupation, annexation, or transfer of control to a moderate Palestinian authority. Regionally, Israel would demonstrate the cost of Hamas’s brutal military venture, deepen its strategic gains against the Iranian-led radical “axis of resistance,” and reinforce its image of determination and deterrence.

However, there is reason to doubt that at this stage of the war—19 months since it began—the IDF can complete the conquest of the Strip and its cleansing of Hamas. Such a move requires many months of clearing operations, followed by years of continuous limited military operations at a time when fatigue among reserve forces is already evident, and public debate over the war’s goals and costs is growing—and expected to intensify with IDF casualties from Hamas’s guerrilla and terror warfare. Moreover, under President Trump, Israel no longer enjoys diplomatic maneuverability. The US president does not display the sensitivity or value-based commitment to Israeli interests shown by his predecessors. His focus in the Middle East—especially on deals and arrangements in the Gulf—does not align with the interests of the Israeli government, including continued fighting in Gaza.

The “voluntary emigration” component of the plan is also questionable, along with the moral and legal implications of a move likely to be perceived as ethnic cleansing under international law. According to (unverified) surveys, about half the Strip’s residents want to leave, but no Muslim or developed country is known to be willing to absorb hundreds of thousands of Palestinians. It is also unclear whether Palestinians would agree to move to underdeveloped countries. Additionally, the Gulf states could apply economic pressure on President Trump to block implementation of the evacuation plan.

In addition, a move to conquer the Strip could come at the expense of managing military risks in other arenas. On the northern front, there is potential for renewed fighting with Hezbollah in Lebanon and military tensions with the new regime in Syria. The West Bank has persistent potential for escalation. Jordan’s stability is fragile. All this is occurring while the IDF is already dealing with manpower shortages, even before entering to occupy Gaza.

In contrast to the military occupation alternative, the Egyptian proposal appears weaker in terms of demilitarizing Gaza. It lacks a clear disarmament mechanism due to Hamas’s strong opposition and the objection of some Arab states—chiefly Qatar—to disarming Hamas outside the framework of establishing a Palestinian state. In order words, a demand to demilitarize the Strip cannot gain Arab consensus.

Nonetheless, discussions between INSS researchers and various actors in the Arab world have revealed a willingness to formulate broad security guarantees for Israel under the Egyptian plan: the entry of Arab forces (such as from Egypt and the UAE) to maintain public order and prevent Hamas from rearming; deployment of close monitoring and inspection mechanisms throughout Gaza; introduction of a non-Hamas Palestinian internal security force trained in Egypt; Israeli security responsibility along the Gaza border (“the security perimeter”); creation of an effective mechanism to prevent the smuggling of weapons through the Egypt–Gaza border; consent to Israeli operations to neutralize threats; and even agreement to IDF activity in areas without Arab forces. Should Israel demonstrate a willingness to advance the Egyptian proposal, it could influence its components according to its own security interests and military needs.

Economic Costs

“Gideon’s Chariots” is expected to impose heavy budgetary costs on Israel. Operating a military administration and maintaining forces in Gaza are estimated at no less than 25 billion shekels per year, including regular security operations, logistics, construction, and basic infrastructure. In addition, Israel would need to shoulder the burden of providing civil services to Gaza’s residents—water, food, healthcare, and housing—in a reality of nearly complete destruction of infrastructure. This cost is estimated at least another 10 billion shekels. Furthermore, according to Bank of Israel estimates, prolonging the war would reduce GDP by about 0.5% (approximately 10 billion shekels per year), mainly due to decreased labor supply and reserve service demands.

All of these expenses would be borne almost entirely by the state budget, as Gaza is not expected to generate any revenue, and external and humanitarian aid to the population would likely decline significantly. The private economy in Gaza has largely ceased to function, and the local tax system has collapsed, making it impossible to collect taxes from residents to finance the occupation and reconstruction.

In contrast, the Egyptian proposal relies on regional and international funding for Gaza’s reconstruction and involves no Israeli expenditure aside from limited costs for security and civilian cooperation. The involved states—chiefly Egypt and the UAE—and donor countries are interested in a consensual mechanism for demilitarizing Gaza to avoid futile investments if Hamas is able to regroup.

Legal Implications

A prolonged occupation under the “Gideon’s Chariots” plan would impose extensive obligations on Israel as an “occupying power” and full responsibility for the needs of Gaza’s population. Furthermore, the humanitarian component of the operation would complicate Israel’s already complex legal battle, initiated at the war’s outbreak. A mass evacuation of around two million civilians to a small southern enclave, under severe deprivation and with encouragement to emigrate, may be interpreted as illegal and perceived as collective punishment, starvation, expulsion, and forced transfer—possibly ethnic cleansing and even as “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part,” as defined under “genocide.” This interpretation is likely to be used in proceedings at international courts in The Hague to strengthen claims that Israel is committing serious alleged crimes, potentially leading to further warrants and influencing final decisions. It could also result in criminal proceedings, including arrest warrants against Israeli officials, IDF officers, and soldiers in various countries and the International Criminal Court.

The Egyptian proposal, in contrast, involves transferring civil responsibility to moderate Palestinian and Arab actors under international oversight, thereby significantly reducing Israel’s legal exposure.

Diplomatic Implications

The “Gideon’s Chariots” operation could lead to a severe diplomatic crisis regionally and internationally. The mass displacement of civilians and a prolonged occupation would likely erode peace agreements with Egypt and Jordan, freeze normalization with Saudi Arabia, and harm the Abraham Accords. Scenarios of deportation or a Palestinian influx into Sinai would cause a sharp crisis with Egypt, strengthen anti-Israel sentiment on the Arab street, and boost radical Islamist forces at the expense of moderate, pro-Western regimes. The strategic advantages that Israel has gained thus far in the war against the Iran-led radical axis—including in Syria and Lebanon—would erode, and an opportunity to establish a regional coalition with moderate Arab states against Iran and its proxies, as well as against the Muslim Brotherhood axis (led by Turkey and Qatar), would be lost. Additionally, growing international criticism of Israel would intensify and could lead, for the first time, to sanctions and widespread diplomatic isolation by countries that have so far refrained from such measures.

In contrast, the Egyptian plan aligns with regional interests and President Trump’s vision of ending the war and promoting a moderate regional bloc against Iran. It enables broad Arab cooperation, revival of a political process, and official relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia, including high potential for economic and infrastructure joint initiatives. However, its implementation depends on Israel’s consent to include the Palestinian Authority in Gaza’s administration and to develop a demilitarization mechanism.

Social and Political Implications

As the occupation of Gaza is prolonged and the human, economic, and moral costs rise, public criticism will intensify, and social cohesion in Israel will erode. Erosion of reserve forces, loss of contact with hostages, images of Israeli soldiers policing a hostile population, scenes of soldiers harmed while delivering aid, unavoidable friction with Palestinian civilians, and a growing sense of strategic stagnation—all could lead to widespread public protest, delegitimization of the operation, and a more polarized political and social discourse.

The Egyptian proposal does not lead to the complete collapse of Hamas, but it offers a framework for realizing broad national interests: the return of the hostages, cessation of fighting, avoidance of a quagmire in Gaza, creation of reasonable security for the intermediate term, and renewed opportunities for normalization with Saudi Arabia and expansion of the Abraham Accords. However, the lack of a military victory image and the sense of having “conceded to Hamas” may provoke public criticism of the political and military leadership for failing to achieve the war’s objectives.

Conclusion

The “Gideon’s Chariots” plan contains real potential to topple Hamas rule, strengthen Israeli deterrence, and secure full control over Gaza’s security levers. However, it entails heavy costs, including harm to the hostages and loss of information about them; deepening internal divisions due to expected military costs and political fallout; significant economic burdens; high exposure to legal and diplomatic risks; moral consequences of anticipated IDF actions; and loss of the opportunity for normalization and expansion of the Abraham Accords. All this comes at a time when Israel may lack the political, military, and social stamina required to achieve the plan’s goals, which demand a prolonged operation lasting months or even years.

Opposite this plan is the Egyptian proposal—supported by the Arab world and the international community—calling for a ceasefire, the release of the hostages, and the establishment of a technocratic Palestinian administration in Gaza under regional and international auspices. While it involves relinquishing the full military defeat of Hamas, its implementation could enable security stabilization, civilian reconstruction, and an opportunity for regional resolution, reduced international pressure, better risk management in other arenas, and attention to Israel’s internal socio-political crisis.

It is important to note that the Egyptian proposal does not involve a complete halt to IDF freedom of action against Hamas and terror infrastructure in Gaza. Just as Israel continues to strike Hezbollah targets in Lebanon based on a policy of retaining enforcement power, it would be able to act against threats in and from Gaza. If Israel cooperates with the Egyptian initiative and helps shape its details—especially effective demilitarization mechanisms—it can secure its right to self-defense and operational capability in Gaza, under formal and informal understandings with Arab states and the United States, while enabling stabilization processes to erode Hamas’s grip on governance and society.

The choice between the two alternatives is not between “absolute good and evil,” but between a one-dimensional strategy seeking full military victory at high cost and a multi-dimensional strategy that, while accepting a partial military outcome, offers potential for diplomatic and economic gains through cooperation with moderate Arab states, reinforcement of existing peace treaties, and expansion of the Abraham Accords. Both alternatives carry risks—military, strategic, moral, economic, and social. The decision, therefore, depends on defining Israel’s long-term national goals—between a worldview of “forever living by the sword” and one of improved strategic positioning through deeper regional cooperation and political agreements.

Table 1. Comparison Between “Gideon’s Chariots” Plan and the Egyptian Proposal

Table 2. SWOT Analysis of Gideon’s Chariots Plan

(edited by Re’em Cohen)

Table 3. SWOT Analysis of the Egyptian Proposal