Strategic Assessment

This article presents insights from a seminar held by the Institute for National Security Studies on March 6, 2024, which brought together resilience researchers and practitioners engaged in promoting societal resilience on the ground. After preliminary discussions on the concept of resilience and a description of societal resilience in Israel during the war, the article suggests a series of recommendations and outlines for action, focusing mainly on the process of rehabilitating the evacuated communities. We regard this process as crucial, and it also has implications for other aspects of national resilience. We contend that the process of rehabilitation and recovery from the Swords of Iron war demands a comprehensive reorganization at state, local authority and civil society levels, to address the severe disruption and restore resilience. This means finding solutions for a wide range of issues, including reconstruction of communities in the north and south with maximum involvement of the inhabitants in decision-making processes.

Introduction

The attack of October 7 marked a turning point in attitudes to national security, and raised the need to rethink many accepted concepts and perceptions. One of these is the concept of resilience, whose definition and components must be examined anew, along with how they can be measured. The October 7 tragedy and the ongoing war are challenging Israeli societal resilience and constitute an important test case for its solidarity. Studies on societal resilience, and conversations with people on the ground dealing with the challenges created by the tragedy, can contribute to the shaping of strategies and ways of coping with the crisis, helping Israeli society to recover and overcome these difficult challenges. The purpose of this article is to present relevant insights from a seminar held by the Institute for National Security Studies on March 6, 2024, which brought together researchers on resilience and content experts engaged in promoting societal resilience on the ground. The goal was to look at the October 7 tragedy and the ongoing crisis it has created as the possible starting points of processes that could lead to growth and empowerment in Israeli society, and to view resilience as a general term expressing the capacity for a multi-dimensional transformative process in Israeli society, which had been in crisis for several years even before this war began.

The article begins with a discussion on the conceptualization of resilience, and particularly the challenge embodied in the question of whether the definition should include reference to preserving the social identity of the damaged systems. Subsequently, it ponders how to measure resilience, bearing in mind issues that arose during the seminar. The article continues with a presentation of the current state of resilience in Israel, as described in the seminar, based on studies and surveys that were presented, as well as on conversations with people in the field. Our description specifies both the encouraging signs relating to societal resilience and the worrying aspects. Finally, we offer a series of recommendations and outlines for action, focusing mainly on the process of rehabilitating the evacuated communities, based on an understanding that this process is crucial and has implications for other aspects of societal resilience, that were discussed in the seminar.

Conceptualizing Resilience

Resilience is an abstract concept that is often defined differently by scholars in different fields (Southwick et al., 2014), and certainly varies in its popular and inexact usage. The seminar participants provided a generic presentation of the concept: Resilience represents “the ability of (any) system to cope with a severe disturbance or disaster, either natural or caused by humans, to maintain reasonable functional continuity throughout the crisis, to recover (bounce back) quickly and grow (bounce forward) as a result, while keeping its identity and basic values.” This definition is valid for various types of resilience, including national, communal and individual resilience. However, it is possible to be more precise and adapt it to specific aspects of resilience.

As stated above, there is relatively broad consensus that resilience represents the ability of any system to cope successfully and flexibly with a severe disturbance or disaster, whether natural (such as Covid) or man-made (such as the current war being waged by Israel) and recover from it. Resilience is mainly a functional referential framework, enabling the system to operate during and after crises and emergencies. Resilience can refer to individuals, families, communities, societies or even organizations, economies and infrastructures. Together all these should produce national resilience (Kimhi, 2016). However, and as was stressed at the seminar, social or national resilience is not a “collection” of individual, communal or systematic resiliencies, or a simple technical amalgamation of them. There are usually significant gaps between the various components of community, society or nation and the resilience of their components. The puzzle is characterized by a variety of systems and environments requiring a differential approach to the analysis and measurement of the concept within as well as between them (Ungar, 2013).

The October 7 attack, as a particularly disruptive event, highlighted the need to carefully examine the link between societal resilience and the components of social identity of the affected systems at the communal and national levels. There was therefore a proposal to add a component to the definition whereby recovery and growth following a crisis must be done alongside the retention of the basic identity and values of the society. This was based on an understanding that when a crisis and its consequences cause a deep change of this identity and values, amounting to a material change in the society, it is doubtful whether such fundamental change testifies to society’s resilience, or perhaps rather to its vulnerability. A deep change in the basic character of a system, society or country can be perceived as a crisis by itself. On the other hand, some seminar participants argued that an ethical change can also be perceived as a result of a society’s growth and maturing.

For example, in the Israeli context, the basic character of the state—which is currently the subject of an internal debate that itself threatens the resilience of Israeli society—means preserving it as a Jewish and democratic-liberal state. These are the basic values of Israeli society that should be preserved, notwithstanding disagreements over the interaction and hierarchy of these values. It is likely that any change in this character resulting from the current crisis will stand as evidence of the society’s vulnerability and the depth of the crisis, more than of its resilience.

This component of retaining identity and values also presents challenges for research, as it is sometimes hard to define the identity and basic values of a society. Which values can change as part of the recovery process, and which should be retained? For example, there are indications that at present in Israeli society, there is not necessarily sweeping support for the idea of liberal democracy, and the question arises as to whether a shift in this element as an organizing idea of Israeli society would be evidence of its resilience or of its vulnerability.

Measuring Resilience

Apart from conceptualization, other serious questions arose at the seminar regarding the ways in which it is possible and proper to examine and measure resilience in general, and societal resilience in particular (Hosseini et al., 2016). The accepted approach states that a central aspect of the study of resilience is that it must be tested over time, and not at a single point in time. No less important is the comparative aspect (Cutter et al., 2010). This refers to other types of crises, their features and intensity, such as the Covid crisis or the political crises that struck Israel. This also applies to comparisons between Israel and other countries, such as the Ukraine during the ongoing war there. Even more important is the comparison between various groups and communities within Israel, such as kibbutzim, collective settlements, villages and towns, or between various populations such as secular, religious and Haredi, or between Jews and Arabs. In addition, there is a need for comparisons between groups that have been affected by the disruption in different ways, such as comparisons between the evacuated communities or those that were directly affected by the October 7 attack, and the general society in Israel.

Resilience can be measured by combining two approaches. One is based on the (subjective) perception of resilience (Béné et al., 2019), studied mainly through surveys and questionnaires, focus groups or interviews. In addition to the usual problems that characterize studies based on questionnaires and surveys, such as social-desirability bias, some of the factors examined in research on resilience are also particularly hard to define and quantify. As mentioned at the seminar, some of the terms used in questionnaires and surveys can be interpreted in different ways and could create confusion. This is true for both elements of resilience and the concept of resilience itself, which is not very familiar to the general public, who do not generally distinguish between the concept of resilience and the ability to withstand disruptions. All these can affect the results of surveys, so it is advisable to combine a broad range of research methods to examine various populations. It was also stressed that it is best to use mixed methods, such as online questionnaires, telephone surveys and face to face interviews (despite their high cost). There is also a need for focus groups based on population sectors that are affected in particular ways by the situation, such as evacuees from the north and south.

The second approach is based on an examination—preferably ongoing—of the (objective) function of the system under study, in terms of resilience in the face of severe disruption (Enderami et al., 2022). With this approach it is possible to monitor the degree of functional decline expected immediately after the disruption against the expected stages of recovery, based on various measures that refer to the familiar routine of the system before the incident, and changes that occur during and after it. It is possible to use variables at communal, social or even national levels to describe the return to normality (such as schools, workplaces, use of public transport, leisure activities), or recovery of the economy (stock market fluctuations, foreign currency exchange rates, use of credit cards) or demographic changes in specific areas, with a focus on those affected by the disruption being studied.

Research that combines these two approaches facilitates a sophisticated collection of data to create a credible, accurate and durable picture of societal resilience in all its aspects.

Societal Resilience in Israel since October 7—Research Findings and the Discourse at the Seminar

Since October 7, several studies have been carried out in Israel by various research bodies, examining the issue of societal resilience based on data and metrics, mainly from public opinion polls.[1] At the seminar we heard about longitudinal and latitudinal studies from the INSS, based on a focused effort to collect data by the Institute’s Data Center and the ResWell Program at Tel Aviv University. For a deeper and more detailed assessment of societal resilience in Israel at this time, any evaluation of the situation should also incorporate the viewpoints and experiences of people and organizations working with those on the ground and most affected by the situation, such as the evacuees, families of hostages, regular and reserve troops, including the wounded and the bereaved families; but also of people working to remedy the situation, such as volunteers helping populations in distress, or established organizations and institutions such as the management of Tekuma, the Israeli Trauma Coalition and others, whose representatives attended the seminar. They can provide important information and raise issues that are not necessarily expressed in academic studies. The research findings and discussions with people in the field presented at the seminar indicated encouraging trends with respect to societal resilience in Israel, but also worrying aspects. It should be noted that since the seminar, the INSS has conducted further surveys to examine other aspects of societal resilience in Israel. In retrospect it is clear that as the fighting in Gaza continues, the hostage crisis remains without a solution, and the uncertainty in the north continues, there is a discernible rise in signs of the erosion of societal resilience. The findings of these surveys can be found on the Institute’s website.

Before we look at the findings presented at the seminar and the various studies conducted since October 7, we should note that history testifies to Israel and the Jewish people’s great societal resilience ability to recover, even in the face of particularly severe disruptions. The starting point of October 7 reflects a mixed trend regarding aspects of Israel’s resilience. On one hand, the Hamas attack took place against a background of a deep social and political crisis and a clear polarization between different sectors. On the other hand, Israel’s macro-economic situation (as an indication of economic resilience which is one of the components of societal resilience) was reasonable. In spite of the drive for judicial reform before October 7, Israel had a low debt to GDP ratio (about 61 percent), very large foreign currency reserves (some 200 billion dollars) and a low rate of unemployment (about four percent).

Positive Signs

An examination of Israeli societal resilience indicates a number of positive signs regarding the society’s ability to recover. These factors involve Israel’s economic resilience, the fast recovery of the army, the resilience of the relevant communities, the functioning of civil society organizations and the media. Below we will expand on these factors.

Economic Resilience

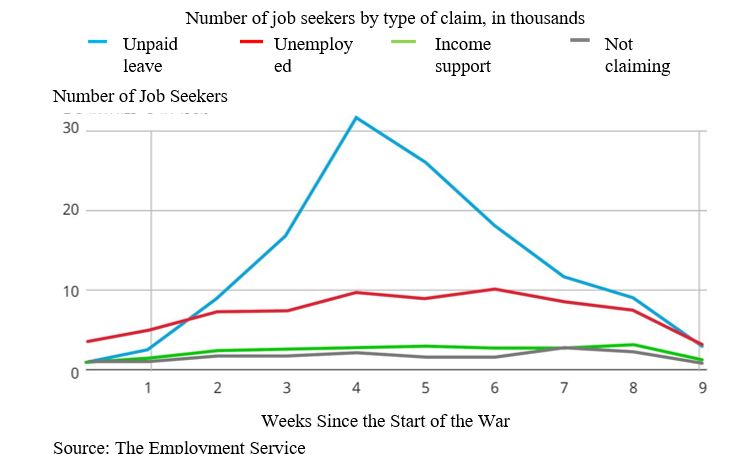

An examination of Israeli economic resilience shows that the positive starting position allowed the makers of fiscal policy in the government and monetary policy in the Bank of Israel, to respond to the situation and reinforce economic resilience, and this had a positive effect on societal resilience. The situation was expressed in the easing of eligibility for unemployment payments for workers who were fired or went on unpaid leave after October 7, and housing grants for evacuees from the western Negev and northern villages. On the monetary level, in the first days of the war the Governor of the Bank of Israel Professor Amir Yaron, inspired faith in the markets when he announced that the Bank of Israel would intervene in the foreign currency market, and thus prevented a sharp devaluation of the shekel against foreign currencies.

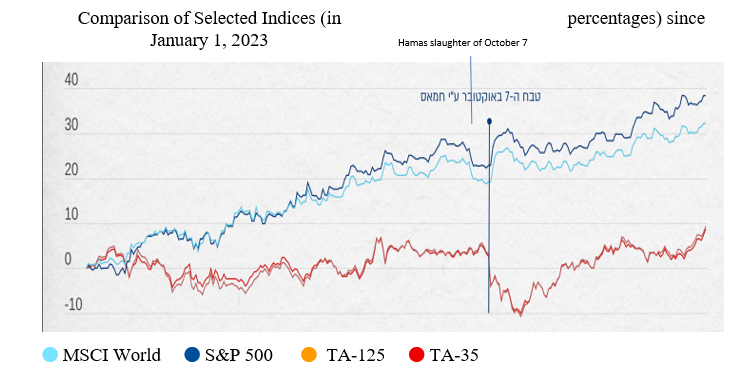

Even in May 2024, in spite of the worrying circumstances, Israel is on a fairly positive economic track in many areas. For example, credit card expenditure has risen, which is a positive economic indicator and evidence of a certain degree of return to normality. The local stock exchange has also shown resilience against the fear of the flight of capital to overseas exchanges because of the war. After a sharp fall in the first days of the war, the local stock exchange indices are higher than before the war. The number of new job seekers has been declining since November, although it did begin to rise during May 2024.These figures indicate the resilience of the Israeli economy. But in order to maintain this positive economic trajectory, in particular after Israel’s credit rating was downgraded by several credit rating agencies, there is a need for a responsible budget policy from the government, and it’s still not clear if that will be achieved.

Figure 1: Rate of Expenditure on Unpaid Leave

Figure 2: The Israeli Stock Exchange

Recovery of the Army

In addition to the positive signs of economic resilience, we can also point to the army’s recovery a few days after the start of the war as an encouraging sign with a positive impact on societal resilience. The functioning of the army, and above all of the reservists, indicates very high recovery ability, evidence of the resilience of the military system. At the same time, in view of the close ties between the army and society in Israel, the swift military recovery also contributed to societal resilience, partly because it reinforced the public’s trust in the IDF, which has been very high and fairly steady since the start of the war. This trust is significant for public resilience.

Resilience of Communities in the Western Negev

The conduct of communities in the Western Negev on October 7 and since then, are also positive signs. This was expressed by their security preparations before the attack (emergency squads) and in the stories of individual heroism on the Black Sabbath, in the border kibbutzim and in Sderot, Ofakim and Netivot. It is also manifest in the impressive arrangements in hotels to receive those who were evacuated from their homes, and no less significant, the way most strove to return to their homes and their communities as soon as possible—many began to return in early March, responding to calls from Tekuma and the IDF. All these are evidence of a reasonable degree of functional continuity in spite of the difficult circumstances after the tragedy, and are the first signs of recovery leading to rehabilitation. This is in contrast to the evacuees from the north, who are still without a glimmer of hope that could awaken signs of recovery among them.

Civil Society and the Media

The functioning of civil society in the emergency was also very impressive, particularly in the initial period, and that helped to maintain functional continuity for communities and individuals, particularly considering the poor performance of government agencies. Apart from maintaining functional continuity, mobilization by civil society organizations also contributed to strengthening solidarity and feelings of personal security among those questioned, which are components of the perception of societal resilience. For example, in the first month of the war, over 70 percent of respondents to the INSS surveys stated that expressions of social solidarity, such as arrangements to collect donations, reinforced their sense of personal security.

As for the established media, although they sometimes arouse discomfort, their mobilization in the struggle was also a positive sign that encouraged social solidarity and identification with the aims of the war. Sometimes the media are criticized for not being critical enough, but their response to the war helped to unite society and reinforce public trust, which are central components of societal resilience.

Worrying Signs

Alongside the positive signs described above, the picture of societal resilience in Israel also includes worrying signs, arousing concerns for the necessary recovery, and consequently for societal resilience. At the seminar it emerged that these signs focused mainly on four aspects: The intensity of the collective trauma, expressed particularly among the evacuees, who had difficulty returning to functional continuity; the defective functioning of the government and fears for the ability of civil society organizations to take its place in the long term; public lack of trust in the government; and social polarization that damages solidarity. Below we will expand on each of these aspects.

Evacuated Communities

The October 7 disaster is an ongoing trauma of considerable intensity. This trauma can still be felt among the citizens of Israel and affects their mood and conduct. There is no doubt that citizens who were directly affected, such as the evacuated communities in the south and the north, are suffering these effects more powerfully. Indications of this can be found in a survey conducted by Tel Hai College and published in January 2024, showing that 48 percent of evacuees and 54 percent of residents who independently left their homes in the north reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

In addition to the findings of surveys, we must refer to other indications. For example, there has been a considerable increase in inquiries received by Resilience Centers. In 2022 the Resilience Centers dealt with some 7,000 clients, while since last October more than 19,000 people have sought their help. In the Western Galilee Resilience Center, demand for assistance rose by 400 percent. This enormous rise in demand makes it hard for the Centers to continue providing professional help to everyone who needs it, affecting the societal resilience of the most vulnerable.

Reports from the field, as expressed at the seminar, indicated severe distress among residents of the western Negev due to the traumatic events, and made worse for the evacuated families by the challenges of feeling like refugees. This was apparently the case to a different extent for the evacuees from the north, whose return home is still uncertain, and they are extremely worried about the state of their villages. Above all this is the issue of the hostages, which affects the entire Israeli public in different ways, and of course has a very difficult effect on their families, who feel that Israeli society is “moving on” towards normality and identifying less with their distress and their public campaign to bring back their loved ones. This can be seen in the decline in the numbers who participate in the rallies in Hostages Square in Tel Aviv. There is a fear of a “breach of the social contract.” The more time that passes without the return of the hostages, the greater the negative impact of this issue on societal resilience, as an open bleeding wound in the fabric of Israeli society.

The issue of functional continuity of Israeli society must also be examined. In this context it is important to distinguish between the functional continuity of the larger section of society that was not directly affected by the October 7 attack and whose situation is relatively normal, and that of those who were directly affected, including the evacuees, the families of the hostages, the families of reservists and others, who are still far from a return to normality. Although the general expectation is for a slow recovery after the war, there must be clear segmentation of groups and institutions. This distinction is important since groups who were most severely affected by the October 7 tragedy and the war are not proportionately represented in surveys, but they have a huge impact on the public mood.

It should be noted that in the western Negev there are some preliminary positive signs of a return to routine, such as the renewed activity of the education system, allowing evacuees to return home. Schools in Sderot have been recording over 50 percent attendance since the beginning of March, and some evacuated families from the town have returned. Nevertheless, the return to these places also raises concerns, particularly in view of ongoing rocket fire from the Gaza Strip (although much reduced from previous levels). In addition, not only is there no progress in sight for the evacuees from the north, but in the absence of an action plan for their return, most are in a state of distress with no hope on the horizon.

Government Function

The problematic conduct of the government, including during the war and on civil issues, raises concerns for its effect on societal resilience. One example can be found in the dismantling of the civilian control center for the war, which was intended to be a non-ministerial body to integrate and guide the work of the various ministries on the civilian side of the war. In effect it was a body with no powers that ultimately disintegrated. Another example was the Defense Minister’s decision in December 2023 to set up a Northern Horizon Administration, inter alia to work on the rehabilitation of infrastructures damaged during the fighting and complete projects to protect villages along the border. The administration raised expectations among residents of the north, who hoped it would operate in a similar way to the work of the Tekuma Administration for residents of the Western Negev, but so far they have been disappointed. These failures make it hard to maintain functional continuity for the relevant communities, as mentioned above, and undermines public trust in the government. While some of this lack of function was balanced by the impressive performance of civil society organizations, there are still substantial concerns over their ability to carry the burden for the long term, and reliance on them also casts a problematic light on the lack of functioning government agencies.

This problem has been intensified by the sense of foot-dragging in the fighting in Gaza, caused partly by the lack of a political plan for the period after the war. Assessments that the war will continue for many more months are deeply worrying for the public, as well as the real fears for functional continuity in the country. The situation on the northern border and the possibility that the fighting will develop into total war with Hezbollah is also a source of public concern, largely due to the organization’s military capability to cause severe damage to the civilian hinterland. The seminar took place before the latest escalation with Iran (April 2024), but it is clear that this has also contributed to doubts over the future.

The multiplying question marks regarding the end of the war and the “day after,” plus the signs of a retreat in international support for Israel, particularly by the United States, arouse considerable fears and criticism of the government’s function. These fears have a negative effect on Israeli society’s societal resilience in the long term.

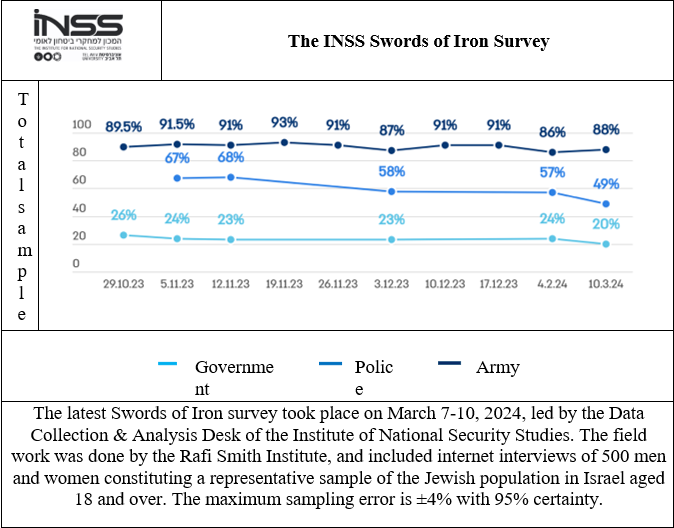

Public Trust

The findings of the surveys conducted by the Institute for National Security Studies show a high degree of trust in the IDF and the Police, even more than in normal times. On the other hand, the data for trust in the government has been consistently very low throughout the war. This is a grave phenomenon that has a serious impact on societal resilience. It is particularly worrying in view of a recent preliminary study conducted by the Samuel Neaman Institute, led by Dr. Reuven Gal, which showed that respondents perceived trust in the leadership and government institutions as the most important factors in societal resilience.

Figure 3: Respondents Who Expressed High or Fairly High Trust in Institutions

It should be noted that the level of trust in the government is naturally higher among those who identify as ideologically right wing, although even here, the survey taken on March 10, 2024 revealed less than half express high or fairly high trust. While the general rate of those expressing trust in the government was 20 percent, among those who identified as right wing the rate was 37 percent, and only 10 percent among those who identified as politically center.

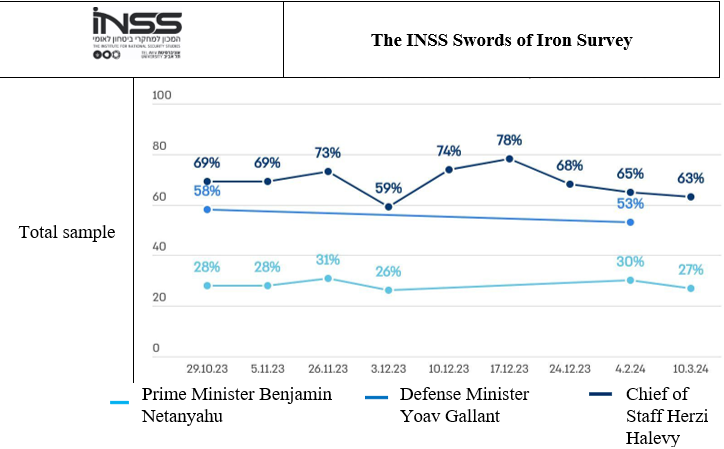

A similar picture emerges from the data on trust in specific individuals. Among the public, the Chief of Staff enjoys a consistently far higher level of trust than the Prime Minister. Political segmentation gives a slightly more complex picture. In the survey conducted on March 10, while the general rate of trust in the Chief of Staff stood at 63 percent, among respondents who identified as right wing this figure fell to 49 percent. On the other hand, among those who identified as centrist the rate rose to 73 percent. Indeed, while the rate of respondents in the sample as a whole expressing trust in the Prime Minister was 27 percent, among right wing voters it was 52 percent (more than for the Chief of Staff). However only 10 percent of respondents who identified as centrist expressed trust in the Prime Minister.

Figure 4: Respondents Who Expressed High or Fairly High Trust in Specific Individuals

Political segmentation shows that lack of trust in the government does not necessarily derive from its conduct during the war, but is the result of political divides that existed before October 7. However, the existence of a low level of trust is a worrying sign in itself with reference to societal resilience. Moreover, and as we discuss below, such gaps in trust between those holding different political views are also a worrying sign, due to the fact that they intensify the polarization of society.

Social Polarization

In addition to these worrying signs, it is impossible to ignore the revival of the polarized political discourse, which is of particular concern for societal resilience. As already mentioned, the October 7 attack was preceded by a grave sociopolitical crisis, which eroded social solidarity and caused very serious damage to trust in state institutions. At the start of the war there was a clear reaction of “rallying round the flag” and it looked like Israeli society was putting the crisis to one side, but recently the polarizing political discourse has returned to center stage—with negative consequences for social solidarity and thus for societal resilience.

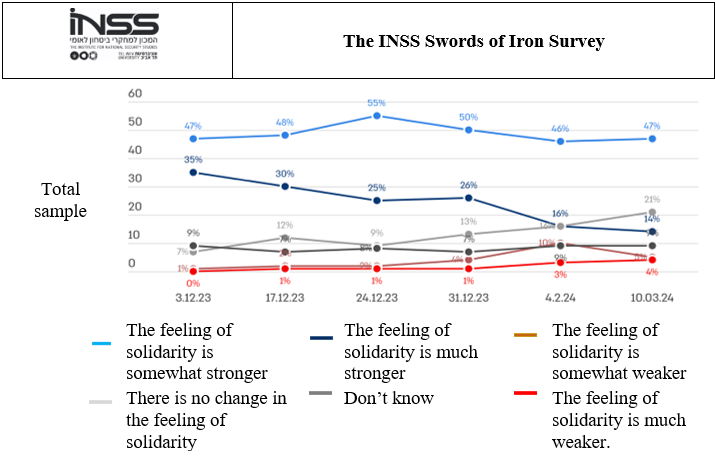

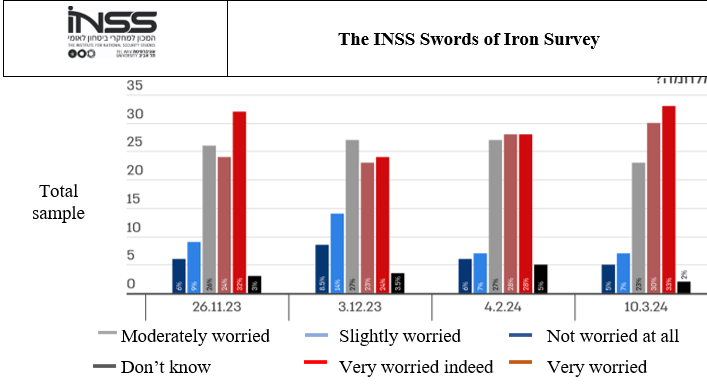

The findings of the INSS surveys show that since the start of the war there has been a decline of about 20 percent in the rate of respondents who believe that the sense of social solidarity has been reinforced. The data referring to those who believe that solidarity in Israeli society is quite strong are consistent throughout the survey period, but it could perhaps be said cautiously that this is mainly a sign of movement between two categories, and still indicates damage to the sense of solidarity. Not only that, but there has also been a significant increase in the number of respondents greatly worried or worried by the state of Israeli society after the war.

Figure 5: In Your Opinion, Has There Been a Change in the Feeling of Solidarity in Israeli Society at This Time?

Figure 6: How Worried Are You About the Situation of Israel on the Day After the War?

Fear of the renewal of the hostile, divisive discourse is reinforced by the study carried out by the ResWell Center, showing that there are considerable differences—in national resilience and in communal and personal resilience—between government supporters and those who define themselves as neutral or opposed to it (Kaim et al., 2024). It is important and interesting to note that among government supporters there were higher levels of resilience than among government opponents. This was also expressed in attitudes towards metrices such as hope and morale. On the other hand, for negative metrices—perception of danger, threats etc.—the levels were higher among government opponents.

It is important to stress that there is a measure of interaction among the factors that are seen as worrying signs with reference to societal resilience. For example, it is clear that the problematic conduct of the government affects both the ability of evacuees to return to normality and public trust in the government. In addition, and as shown above, there are mutual effects between social polarization and public trust in the government. These interactions intensify the worrying signs, increase their effect and stress the importance of finding a total systemic solution, as specified in the section on recommendations.

Recommendations and Outlines for Action

Societal resilience is a highly important factor in national security in general, and in the current crisis in particular. In order to repair societal resilience in Israel and lead Israeli society from crisis towards recovery and growth, it is vital to strengthen awareness of resilience among the public and national and local leaders, and create plans of action directed towards various objectives. Such plans must support the implementation of programs that combine research insights and theories on the subject of resilience, as discussed at the seminar, with government and local authority policies and with the perceptions and needs of the public in general, and of the groups directly affected by the ongoing crisis in particular. Against this background, we present a number of recommendations and suggested actions to strengthen societal resilience in Israel and help its society to recover from the October 7 tragedy.

First of all, the return of all the hostages, the rehabilitation of the border settlements that were damaged and the residents who were uprooted from their homes during this war, and the revival of their sense of security—all these must be included in the aims of the war. This is according to the perception that victory means achieving all the war aims, whose main purpose must be a significant and sustainable improvement in the security situation, with the emphasis on long term settlement along the borders. These concrete objectives must be prioritized while internalizing the basic understanding that the overriding aim of the process is not only rehabilitation or bouncing back, which means returning to the situation before October 7, but bouncing forward, which means multidimensional renewal and growth at the national and local level. The issues of the hostages and the damaged villages have a bearing on many of the worrying signs with respect to resilience. They affect not only the evacuees themselves, but how the public perceive the actions of the government, and consequently public trust in the government, and are therefore a central building block in the process of strengthening resilience. They also have considerable impact on the functional continuity of Israeli society, and as a result, also on the functional measures of resilience, such as economic recovery.

The rehabilitation process, and above all recovery and growth, is expected to be long, challenging and full of pitfalls. It must be tackled with a total systemic approach, based on awareness of the time dimension and the responsibility of the state and the government to achieve these objectives. In view of the magnitude of the disaster and its unprecedented physical and mental impact, the process must therefore be understood as a long-term project. It is important to remember that although part of Israeli society is drawing near to the “day after,” for wide sections of the population the war has not ended and this sensation was expressed by one of the speakers at the seminar who stated: “We are always before the event, in the event, and after the event.” So even when the process of recovery begins, it will be multidimensional, since every section and group of the population require components of recovery and incentives for growth based on their needs, characteristics and wishes. This must be the working assumption for everyone involved in the task: Avoid a generalized approach to the public as a whole in favor of a differential and compassionate approach, by paying attention to each group separately.

Based on the lessons of previous catastrophes worldwide, the professional literature proposes a number of basic principles that can significantly improve the success of rehabilitation and recovery processes. These principles were presented at the seminar, and should be studied and implemented with respect to the current situation, and adapted to local circumstances. It is important to stress that the main recommendations in this context deal with the evacuated communities, based on the understanding that the crisis they are experiencing is the most severe and therefore requires most action, but also because the treatment of the evacuees will have a significant effect on other measures of resilience, and particularly those that were noted as worrying at the seminar.

- The government has overall responsibility for planning, budgeting and directing the practical work of rehabilitation. This requires firstly an understanding of the task and its importance as a national priority to renew perceptions of national security. Just as the government must shape the future components of physical security, with an emphasis on the perception of military security and including financial components, so it is also obliged to include societal resilience as a component of security of the first rank. This requires a government that is aware, committed and working for optimum repair of the damage caused by the disaster. It is also important to understand that the rehabilitation process must be focused on growth—not just a restoration of the previous situation, but the recovery and rehabilitation of the relevant regions (although there are broad differences between them) in a way that constitutes a leap forward relative to their situation before the crisis.

- The processes of strengthening social, national and communal resilience must start from below, from the people and communities themselves. Studies examining ways of making decisions in complex processes of recovery found that too often they are characterized by bureaucratic procedures with little representation of individuals, communities and minorities; often excluding women, people with special needs, and civil society organizations. The first and most important step is to optimally integrate all these elements into the process of making decisions, planning and implementing rehabilitation; just as the Tekuma Administration is already operating, other administrations must be established for other sectors. Residents of the Western Negev and of the north stress again and again that they want and demand to be part of the process of decision making. Their practical involvement is necessary for decisions affecting the immediate, medium and long term. For example, a poll of residents of the Eshkol Regional Council stressed that many of them wished to live in one place in the Eshkol Region until they could return home, and that many sought to retain the familiar character of their villages before the disaster. This links to the principle stated above, of the need to maintain the identity and values of the system being rehabilitated.

- The integration of citizens into the decision-making process has a number of important consequences. It increases the chance that the decisions and programs will faithfully reflect the wishes and needs of the inhabitants and the communities. Experience so far shows that this is not happening enough. Not only that, but incorporation of the residents also raises awareness of aspects that external decision makers do not always take into account. For example, when the villages were evacuated, not enough thought was given to all the implications of the long-term housing of evacuees in hotels, which present difficult challenges to the family structure. It should be noted that as of March 26, more than 20,000 evacuees from the north and about 7,000 from the south were living in hotels. Thus many evacuated families have been living for months in a challenging and frustrating physical situation. Conversations with the evacuees create the impression that decision makers are not sufficiently aware of these difficulties and are not looking for more suitable solutions. Involving the public in the processes will also restore to the residents a sense of competency and control over their lives, something that was badly damaged by the trauma. It should also restore their faith in the system.

- It appears that members of the Tekuma Administration are aware of this need and its representatives are therefore careful to state that it involves the public in its decision making from the start. Thus they reported on meetings with residents and “round table” discussions with experts, including contacts with local authorities in the western Negev. Nevertheless the question arises of whether they are just listening to the residents, or whether decisions actually reflect the perceptions and needs that are expressed. Voices from the field indicate that there is still a long way to go in this vital aspect.

- While the Tekuma Administration is taking the first steps to rehabilitate the western Negev towns and villages, there is no systemic organization to tackle the challenges of the many evacuated northern villages. Neither is there a national organization to deal with the present situation and potential challenges with the possible spread of the war to the northern arena. This is a clear omission requiring immediate steps to rectify the situation, and to improve all elements of national readiness for a lengthy war. The demand for such a systemic organization is also heard from the ground, as shown by the letter sent by the heads of northern local authorities to the Prime Minister on March 10, in which they demanded security solutions to the threat from Hezbollah and a plan to strengthen the north.

- Another important principle for strengthening resilience is the emphasis on establishing the social capital of the affected communities. While most of the processes of recovering from disaster have a tendency to stress the physical dimension, thought should also be given to the fact that real resilience comes from the level of bonding, bridging and linking social capital in the community (Aldrich, 2017). Of these the most important is bridging social capital, which can be built via public spaces—parks, community centers, synagogues, restaurants and so on. This can be seen for example in Ein HaBesor, which is rehabilitating itself independently. It is important to stress that in times of peace, the distribution of sites that give rise to social capital is not equal and there are gaps between communities. While some communities have many parks and public spaces, for example, in others there are fewer. Since many of the communities attacked on October 7 were part of the social and geographical periphery of Israel, the rehabilitation process must include the construction of social infrastructures to help these communities build the social capital that will help to repair their resilience. It appears that the bodies involved in the rehabilitation process are aware of this issue and are making an effort to include social aspects as part of the physical process. For example, the Tekuma Administration is striving to establish regional sports centers and cultural centers as part of the plans, as well as reinforcing the local education system, with attention paid to the needs of the residents.

- In the field of mental health and psychosocial support, empowering resilience occupies an important place. In the immediate term, the trauma means there are many individuals suffering from mental illness of various degrees of intensity and requiring professional treatment. There is also a need for psychosocial first aid, which means training people on the ground to tackle these issues and reinforce social networks in the community. The network of resilience centers (which now also exist among concentrations of evacuees all over the country) are a central factor in this essential work. The fact that resilience centers were familiar to the communities and used by them for many years before the disaster makes them a very significant element in the current situation. Resilience centers offer therapists who themselves experienced the disaster and this makes it easier for them to create a shared reality, experience and therapeutic language with their patients.

- Another principle behind successful rehabilitation is coordination and collaboration between the various elements. In this context it is important to note that the affected Gaza-border communities do not comprise a single legal entity and are not all included in the various local councils and local authorities with which the Tekuma Administration is working. Here there is the challenge of overcoming the differences between the towns and villages, in their character and their distance from the Gaza border, which stresses even more the need for coordination and systemic capacity. Reports from the ground sometimes indicate gaps and obstacles between government ministries and the government’s Tekuma Administration, between it and the local authorities, and between them and the various communities and residents. Bridging all these gaps is a challenging task for all of the parties involved. In the current circumstances this requires sensitivity and a differential approach, including for small groups of citizens, particularly those with special needs.

- The welcome activity of civil society organizations can be seen in their impressive readiness to provide a response to citizens in distress. This had far-reaching importance, particularly at the start of the war, when government ministries were having great difficulty in functioning. Recently there have been more signs indicating a degree of “fatigue” in these organizations and their difficulty in maintaining the level of assistance required for the long term. Clearly they are unable to provide a sufficient response to all the long-term needs of the residents, particularly with respect to general needs such as health, education, welfare and employment. In a situation where neither the government nor the local authorities have the absolute ability to meet all the needs, a way must be found to coordinate between them and the volunteer organizations in order to maximize their efficiency and ensure that they are serving the needs of the residents.

If the parties responsible for rehabilitation adopt these recommendations, the process of rehabilitating the evacuated communities will likely be more effective. This will reinforce functional continuity and show that the government is back on track, which will have a positive influence on societal resilience. At the same time public faith in the government may improve and polarization in society may even be reduced. In addition to these steps, the government should act independently to reinforce these aspects of resilience, for example by avoiding toxic and harmful political discourse that bolsters polarization and undermines public trust.

To sum up, the process of repair and recovery from the Swords of Iron War requires the government, the local authorities and civil society to take immediate and comprehensive measures to tackle the severe disruption and rehabilitate societal resilience. In this paper we have outlined a conceptual framework based on in-depth studies and experience from Israel and elsewhere, as well as insights that arose from studies carried out during the war and conversations with elements on the ground as presented at the seminar.

This framework should set guidelines for overall planning and management of the effort that is required right now, and will be even more necessary in the coming years. At present there is a need for a new and different national civilian trajectory, based on components of national resilience, that can lead Israel and its citizens to extensive recovery and renewed growth as fast as possible. All this in conjunction with the security establishment’s process of recovery. According to the research on civil society during war, it appears that such a trajectory can only happen if it is coupled with a multidimensional reboot of government systems and their connections to civil society, which would bring about a change in Israel’s order of priorities.

References

Aldrich, D.P. (2017). The importance of social capital in building community resilience. In W. Yan & W. Galloway (Eds.), Rethinking resilience, adaptation and transformation in a time of change (pp.357-364) Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50171-0_23

Béné, C., Frankenberger, T., Griffin, T., Langworthy, M., Mueller, M., & Martin, S. (2019). ‘Perception matters’: New insights into the subjective dimension of resilience in the context of humanitarian and food security crises. Progress in Development Studies, 19(3), 186-210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1464993419850304

Cutter, S.L., Burton, C.G., & Emrich, C.T. (2010). Disaster resilience indicators for benchmarking baseline conditions. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 7(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.2202/1547-7355.1732

Enderami, S.A., Sutley, E.J., & Hofmeyer, S.L. (2022). Defining organizational functionality for evaluation of post-disaster community resilience. Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure, 7(5), 606-623. https://doi.org/10.1080/23789689.2021.1980300

Hosseini, S., Barker, K., & Ramirez-Marquez, J.E. (2016). A review of definitions and measures of system resilience. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 145, 47-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2015.08.006

Kaim, A., Siman Tov, M., Kimhi, S., Marciano, H., Eshel, Y., & Adini, B. (2024). A longitudinal study of societal resilience and its predictors during the Israel-Gaza war. Applied Psychology: Health and Well Being, 1-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12539

Kimhi, S. (2016). Levels of resilience: Associations among individual, community, and national resilience. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(2), 164-170. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910531452400

Kimchi, S., Eshel, Y., Marciano, H., Kaim, A., Adini, B. (2024a, 28 January). Population resilience and metrices of coping over three repeated measurements during the current war. Reswell. https://tinyurl.com/muw9wbkn

Kimchi, S., Eshel, Y., Marciano, H., Kaim, A., Adini, B. (2024b, February). The link between population resilience and metrices of coping, and the degree of support of the government – 3 months after the start of the war. Reswell. https://tinyurl.com/5n75nfyz

Southwick, S.M., Bonanno, G.A., Masten, A.S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25338. https://doi.org/10.3402%2Fejpt.v5.25338

Ungar, M. (2013). Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(3), 255-266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013487805.

____________

[1] The INSS surveys can be found at https://tinyurl.com/3bmdjj63. For insights that arose from the surveys of the ResWell Program, see Kimchi et al., 2024a, 2024b; Kaim et al. 2024. There was also a presentation at the seminar of a preliminary unpublished study from the Samuel Neaman Institute led by Dr. Reuven Gal, and surveys conducted by Prof. Yftach Gepner among residents of the Eshkol Regional Council, that can be found at https://tinyurl.com/y3s7t94j.