Strategic Assessment

The adoption of Resolution 922 by the Israeli government was a significant effort to accelerate economic development within the Arab population. The program rested on two primary objectives: economic development among the Arab sector and its integration in the Israeli economy and society; and a narrowing of the existing wide socioeconomic gaps between the Arab sector and the general population. Six years later, in October 2021, the government passed a new five-year plan with similar objectives, but with a budget three times as large as the previous budget and new areas for development. This article examines the main principles of Resolution 922, its implementation, the hurdles it faced, and the lessons that can be drawn from the six years it was in effect. It then examines the primary elements of the new resolution, based on the lessons of the preceding experience.

Keywords: Arab society, five-year plan, economic development, education, healthcare, transportation, infrastructure, employment, local authorities

Introduction

In December 2015, the government of Israel adopted Resolution 922, “Government Activity for Economic Development of Minority Populations in the Years 2016-2020” (Prime Minister’s Office, 2015). The plan was formulated by the Budgets Department in the Ministry of Finance, along with representatives from the Arab population in Israel. The Ministry of Social Equality, via the Authority for Economic Development of Arab Society, was to be responsible for implementation of the plan, in coordination with the relevant ministries and the Finance Ministry’s Budget Division, and in partnership with various local Arab authorities.

At the outset, it was announced that the plan was allocated a budget of NIS 15 billion, of which NIS 5.8 billion was to be directed to the Arab education system. In fact, however, the total budget for Resolution 922 was about NIS 10 billion, not including the allocation for education. The plan was intended as a catalyst for the economic integration of Arab society in Israel, to help this sector realize its potential and serve as an important growth engine for the Israeli economy. The plan centered on two main objectives: the economic development of the Arab population and its integration into Israeli society; and a narrowing of the wide socioeconomic gaps between the Arab sector and the general population. The plan focused on areas where the existing gaps were particularly prominent, such as housing, transportation, education (both K-12 and higher education), employment, and the capabilities of the Arab local authorities.

The singular aspect of this plan, the first of its kind and scope for Arab society, was its fundamental change of how resources—and budgets in particular—are allocated to Arab communities in Israel. The new allocation system aimed to establish an ongoing adjustment of resources, based on the percentage of the Arab population among the greater population. The plan’s intent was to establish a government allocation of 20-40 percent (according to the proportion of the Arab population relative to other sectors) in the fields of education, construction, infrastructure, and public transportation. The hope was that the plan would help reduce the bias in the allocation of state resources vis-à-vis Arab society relative to Jewish communities, and in turn, effect a more equal distribution of resources between Jews and Arabs.

The development of this plan continued with the formation of Israel’s 36th government, based on a coalition including, for the first time in the country’s history, an Arab party. In October 2021, the government approved a second five-year plan (Resolution 550), at which point the first plan was extended for another year. The budget of the second five-year plan is three times larger than that of the previous plan, and also includes new areas for development in Arab society.

This article looks first at the central principles of Resolution 922, elements of its implementation, the obstacles it encountered in its six years of operation, and the main lessons that can be drawn from the implementation of the plan. It then examines the main components of the new plan (550) based on the lessons of 922.[1]

Background and Main Purposes of Resolution 922

Integration of the Arab population into the Israeli economy is an issue with far-reaching economic, social, and political implications for the state. After decades of neglect, on December 30, 2015, the government adopted a five-year plan for the economic development of the Arab sector. From the outset, the plan was revolutionary in nature, with strategic importance of the highest order. It was adopted by a right wing coalition government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Finance Minister Moshe Kahlon, following a determined initiative by Amir Levi, who was then the budget director at the Finance Ministry. Levi, together with the head of the Minorities Economic Development Authority, Iman Saif, saw the reduction of economic gaps as a long-term strategic objective. In particular, they sought a focused effort to increase productivity in the large Arab sector (as well as in ultra-Orthodox society), with the aim of increasing Israel’s overall productivity in a relatively short period of time (Levi & Suchi, 2018). As such, the main effort of this plan focused on initiatives to facilitate the wider integration of Arab citizens into the workforce. This effort was also based on an understanding across the entire political and public spectrum that it was necessary to deal with the deep-seated economic and social problems in Arab society—problems that impede potentially significant gains for the broader Israeli economy.

An analysis of Resolution 922, its aims, and the obstacles it faced, begins with a review of the unstable foundation on which the plan was built in 2015, in five interlinked areas:

- The economy: Over the years, the economic gaps between the Arab and Jewish populations grew steadily wider (CBS, 2022). For example, in terms of salary differentials: according to data from the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) in 2015, the average gross monthly income of a Jewish man was NIS 12,316, compared to NIS 6,564 for an Arab man (Hadad Haj Yihyeh et al., 2022). Poverty among Arab families stood at about 60 percent, with over 50 percent of Arab children living in poverty.

- Employment: The limited integration of Arab women into the workforce (about 74 percent were not working before the launch of the first 5-year plan) was, and is, a central component underlying the high poverty rate of Arab families. On the other hand, approximately 70 percent of Arab men are employed—similar to the rate among Jewish (including ultra-Orthodox) men. However, unlike Jewish men, most Arab men are employed in fields such as construction, industry, commerce, and transportation, where both skill levels and pay are low compared to other fields (CBS, 2020, table 9.18).

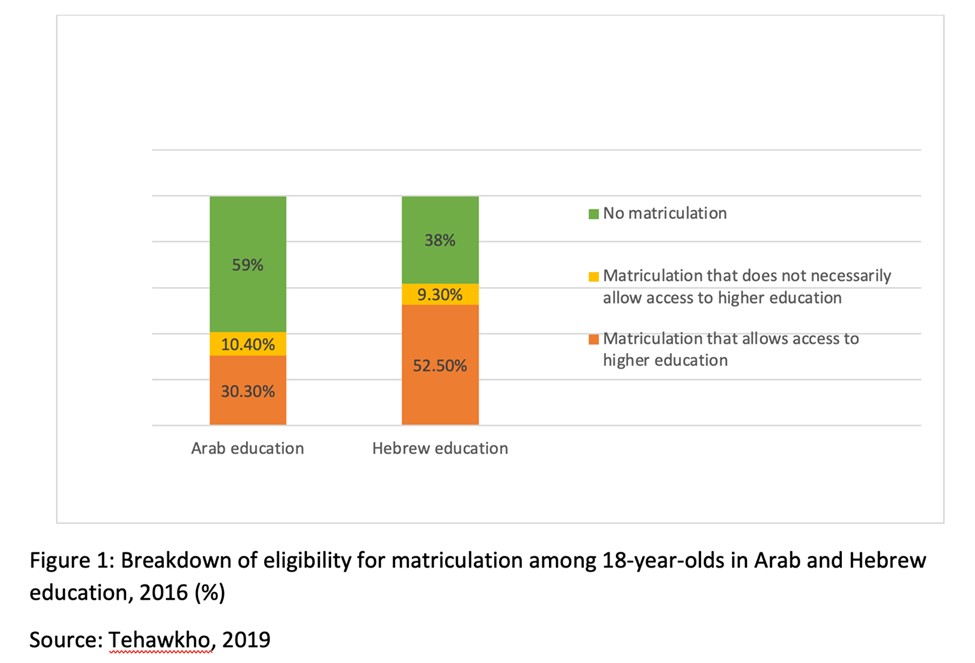

- Education: The rise in poverty and salary gaps traditionally stemmed from the significant educational gap between Jews and Arabs (Blas, 2020). Since 2000 there has indeed been a steady rise in Arab educational achievement, but before the launch of Resolution 922 only one-tenth of college and university students in Israel were Arabs, and only approximately 50 percent of Arab youth completed high school (Figure 1).

- Transportation infrastructure: The link between transportation infrastructure and employment is clear, particularly among the Arab population, many of whom live relatively far from employment centers and the primary institutions of higher education. Before the launch of the plan, 94 percent of Arabs lived in towns and villages with undeveloped transportation and other infrastructure (Lavie, 2016, p. 66).

- Healthcare: The life expectancy of Arab citizens was on average four years less than that of Jewish citizens. Also, data from the CBS socioeconomic survey show that one-fifth of Arabs who were prescribed medication for health problems did not buy the drugs, mainly because of their economic situation (Alizera, 2018), and that infant mortality in Arab society is three times higher than infant mortality rates in Jewish society (Doctors Only, 2017).

These sobering figures reveal a difficult picture of deep-rooted obstacles, which the state did not address sufficiently. Between 2000 and December 2015, the government passed a series of resolutions concerning the development of Arab towns and villages, but the budgets allocated were less than what was necessary, and as such, the results were insufficient (Lavie, 2016). Against this background, Resolution 922 represented a dramatic change in the government’s approach to Arab society, and a genuine effort to strengthen it in areas that until then had been neglected.

Main Points of Resolution 922

The main elements and goals of the plan, as they were presented in 2015, are as follows (Prime Minister’s Office, 2015):

- Education: The five-year plan budget was split (for bureaucratic and other reasons) between Resolution 922 and a separate government resolution— 1560, of May 19, 2016 (Prime Minister’s Office, 2016). With respect to formal education, the relevant items in 922 dealt with improving educational quality by raising the requirements for teachers and investing in their training, mainly in core subjects. At the same time, NIS 650 million were allocated to the development of informal education. The latter resolution (in effect, separate from 922), with a budget of NIS 5.8 billion, dealt with improving the academic achievements of Arab students and defined four objectives: (1) a 14 percent increase in the proportion of grade 12 students eligible for a matriculation certificate (which stood at 59 percent); (2) an increase in the achievements of at least 50 percent Arab students; (3) an increase of 17.5 percent in the rate of students eligible for a matriculation certificate that meets the conditions necessary for higher education (based on 40 percent in 2016); (4) a decrease of 2.5 percent in the student dropout rate, which would not exceed 3 percent of all students.

- Higher education: The targets set in the original resolution referred to students registered for (rather than completing) degrees in universities and colleges. The target for registration rates for undergraduate degrees among minorities was set at 17 percent—12 percent for Master’s degrees and 7 percent for doctoral degrees.

- Employment: The plan aimed to increase employment rates and pay for minorities in Israel. With this goal in mind, NIS 250 million were allocated to operate 21 employment guidance centers, joining an investment of NIS 231 million in day care centers, in order to encourage Arab women to work outside the home. Indeed, 25 percent of the budget for construction of day care centers was directed to Arab communities.

- Public transportation: At least 40 percent of the total additional budgets allocated to public transportation were earmarked for towns and villages with minority populations, so that by 2022 these places would have equal access to public transportation. The comparison was to be measured by frequency, level of coverage, and number of destinations. The resolution also included budgets to improve urban and inter-urban roads.

Implementation of Resolution 922

There is a natural, expected gap between every plan and its implementation, and this applies to the first five-year plan for Arab society as well, which from the start represented a new approach both in terms of its geographical and financial scope (Citizen Empowerment Center, 2021). For Arabs in Israel, the strategic importance of the government move behind Resolution 922 cannot be overstated. The fact that the government adopted such a comprehensive, large-scale plan, dealing in such detail with a whole range of programs for essential areas of development, was nothing less than a fundamental paradigm shift. It was also important because it embodied recognition of the government’s many years of neglect of Arab society, amounting to severe institutional discrimination, and in turn signaled the conscious recognition of the government’s intention to change longstanding policies. All analyses about the execution of this plan must be viewed from this perspective.

According to the official summary presented in June 2021 by the Minister for Social Equality and the head of the Minorities Economic Development Authority (Ministry for Social Equality, 2021b), Resolution 922 was allocated a budget of about NIS 10 billion, of which some NIS 9.6 billion were actually distributed, as follows: NIS 4.58 billion for physical infrastructures, NIS 1.08 billion for employment and economy, NIS 1.14 billion for education[2] and higher education, NIS 1.38 billion for society and community, and NIS 1.41 billion for strengthening local authorities. Out of the overall budget for the plan, about NIS 6 billion was spent on other various projects, representing 62 percent of the allocation.

The official figures published for the rate of planned versus actual results do not provide a full picture of the plan’s achievements. Most of the figures represent inputs rather than outputs. The budgets for Resolution 922 were transferred from the Finance Ministry directly to the government ministries responsible for executing the programs, and these ministries did not always publish detailed figures of their performance (neither in general nor with reference to the plan under discussion). During the years of implementation, the extent of cooperation between the different working levels of senior ministry officials, the Authority for Economic Development of Minorities, and the heads of Arab local authorities varied. Knesset members from the Joint List assisted in the work, as well as organizations in Arab civilian society such as the Mossawa Center, the Sikkuy Association, and the Arab Center for Alternative Planning. What follows is a general assessment of implementation in the main areas:

Education: A survey of budget data gives a partial picture of the results of the investment in the framework of the first five-year plan. It appears that most of the investment did indeed reach the education system. Differential budgets were allocated to the various elements of formal education (Civilian Empowerment Center, 2021), but it is hard to assess their direct impact on student achievement. NIS 200 million were invested in the professional development and training of Arab teachers. Regarding informal education, the plan was implemented in 76 local authorities, where activities in community centers and youth movements were extended, and the Etgarim (“Challenges”) movement was set up to reinforce social skills and self-actualization.

In terms of achievement, it is hard to obtain a full picture from the Ministry of Education that clearly shows the impact of the investment on Arab student achievement. Although the budget increased considerably, that is only one variable of many in this sensitive field. According to a report from the Citizen Empowerment Center, most of the defined objectives were not achieved, including: a smaller gap between Arabic speakers and Hebrew speakers in the school effectiveness tests (Meitzav) in science and technology, mathematics, and English; an increase in the percentage of students eligible for matriculation; and an increase the percentage of students taking five study units for the matriculation exams in mathematics. On the other hand, the defined objectives were achieved in the Meitzav tests in Arabic, and the dropout rate declined.

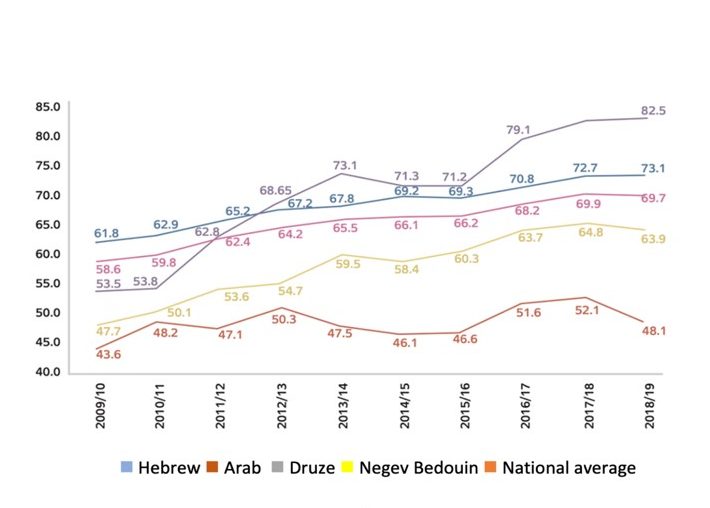

There have apparently been further improvements in recent years, and in general, it is possible to point to a trend of narrower gaps in achievement between students in the Arab education system and their Jewish-Israeli counterparts. Nevertheless, in most parameters, there are still gaps that affect the chances of Arab students of reaching higher education and high-quality employment (Citizen Empowerment Center, 2021). In addition, there are various trends in the educational achievements of the Arab population in Israel that indicate the persistence of large gaps between different groups of Arabs, particularly the Bedouins (Figure 2).

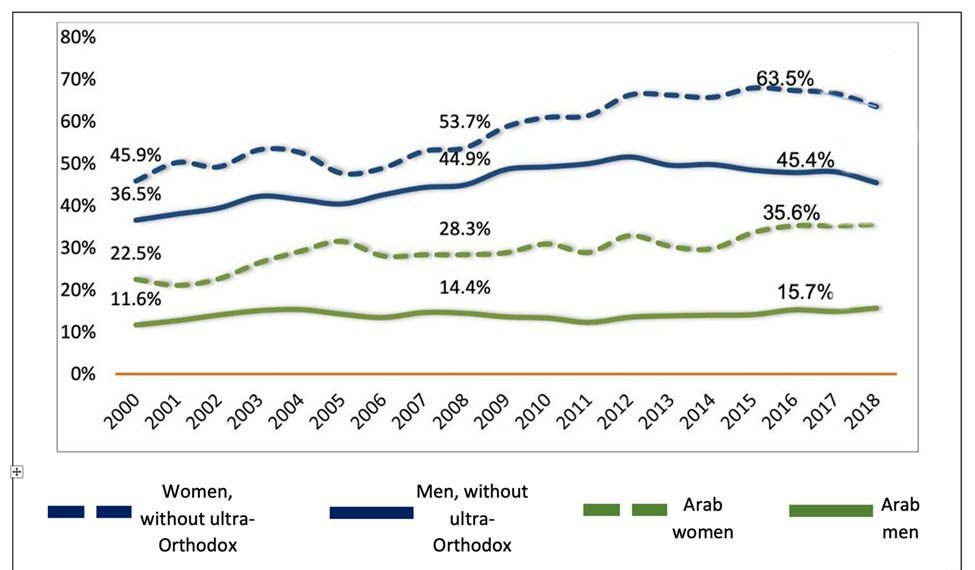

- Higher education: This area stands out as an exception in which the five-year plan managed to reach and even exceed some of the defined objectives, mainly with respect to the numbers of Arab students registering for higher education (Figure 3). The budget allocated to higher education was NIS 550 million (Krill & Amariya, 2019). In the 2019-2020 academic year (), Arab students accounted for 18 percent of all undergraduate students in higher education institutions in Israel, 15 percent of the students pursuing Master’s degrees, and 7 percent of doctoral students (Council for Higher Education, 2021). However, the first plan did not set defined targets and there was insufficient attention to student dropouts, particularly among men, so that the gap between Jewish society (without the ultra-Orthodox) and Arab society remained very high. This is significant not only in quantitative terms, but also in other ways, particularly in light of the relatively large number of Arab students who study in Jordan and the West Bank (Center for Research & Information, 2021).

- Employment: A review of this area is difficult, primarily because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which broke out in the fifth year of 922 and led to increased unemployment. The pandemic caused considerable harm to low-skilled workers from the lower socioeconomic categories, and because most Arab workers are among this low-skilled group, the damage to the Arab workforce was significantly greater than that to the Jewish workforce (excluding the ultra-Orthodox). However, a precise examination of trends shows that even before the pandemic, there was a decline in the proportion of Arab men in the workforce. In contrast, an examination of employment trends shows an increase in the employment of women. In fact, even before the pandemic, the proportion of working women exceeded 40 percent. At the same time, the wages of men and women in Arab society rose by more than NIS 1,000, although during these years the Israeli economy experienced significant growth, coinciding with an increase in average wages more broadly. Therefore, it is not clear how much, if at all, government efforts on this subject contributed to the salary increase. Moreover, the annual investment in the construction of day care centers to encourage female employment did not reach the required minimum of 25 percent. On the other hand, performance in the field of employment placement was good, and in line with the original plan (Table 1).

Table 1: Employment and economy

| Activity and Selected Achievements | |

| Ministry of Labor, Welfare and Social Services | Ministry of the Economy |

| · Budgeted construction of 55 day care centers in minority locations during 2016-2019 · 30,072 placements in Ryan Centers[3] from early 2016 to the end of 2020 · Increase in the rate of employment of Arab women | · Cumulative support of about 21,500 small and medium-sized businesses by the derivatives market · Assistance to 70 companies in the “Smart Money” plan to support exporters · Wage subsidies for 2,558 jobs in an employer incentive program · Investment of NIS 400M in industrial zones in minority towns and villages |

Source: Ministry of Social Equality, 2021c, p. 28.

- Housing and urban planning: The plan included announcements from a few ministries about the allocation of budgets to complete the outline plan to promote detailed planning, finance plans for registering and regulating land, and register plans for unification and division of land for the construction of public institutions; maintain the open spaces intended for local authorities; and subsidize the development costs for the purposes of dense construction.

The timing of the first five-year plan was linked to the implementation of the comprehensive reform of planning and construction in the country, which was approved in March 2014, and intended to reduce bureaucracy and waiting times for various approvals, and thus simplify the planning and construction processes. The inclusion of these plans paved the way for preparing land for residential construction and regional employment development for Arab society as well. For example, the work plan of the Planning Administration in the Finance Ministry included plans for construction of residential units in Arab towns, on private land and on state land, to an extent matching their share of the population. Some of them involved the Committee to Promote Preferential Housing areas. Construction also began on public buildings and on plans for denser construction in some Arab towns.

- Infrastructure and Public Transportation: The data published by the Ministry of Transport indicate that 84 percent of the targets defined for the end of 2020 were achieved. However, the Citizen Empowerment Center found that there is still a very large gap between the level of public transportation in minority towns and villages and the country overall in the defined parameters. Inter alia, this refers to infrastructure and public transportation elements that have not been implemented; namely, the scope of projects involving local authorities has not increased and cross-town roads have not been developed (Table 2).

Table 2. Physical infrastructures

| Activity in this field and selected achievements | |

| Ministry of Housing: · Budgeting for 128 public institution projects, and completion of 26 projects · Signing strategic and focused planning agreements with local authorities | Government Water and Sewage Authority: · Over 86 projects to build and upgrade infrastructure in minority towns · Rate of sewage connection increased to 90 percent |

| Ministry of Transport: · Execution of 82 urban road projects in local authorities · Increase in the number of towns and villages with public transportation | Planning Administration: · Completion of outline plans for 20 local authorities · Some 23 strategic planners recruited for 23 local authorities |

Source: Ministry of Social Equality, 2021c, p. 25

The Entrenched Obstacles facing Program Implementation in Arab Society

It is not surprising that following years of neglect of Arab society by the state, the first five-year plan encountered significant obstacles that disrupted or delayed the implementation of the various programs. The government also recognized these obstacles (Ministry for Social Equality, 2021b), and while acknowledging that Resolution 922 saw some significant achievements, the general picture appears mixed. The main problem concerning the advancement of Arab society in Israel through five-year plans is not only one of budgets and financial resources, although these factors are certainly important. Rather, the main problem is the existence of clear barriers in the complex links between the state and its mechanisms and Arab society itself, with its capacity to assume responsibility for the progress and implementation of the plans. A report from the Economic Development Authority on the implementation of Resolution 922 elaborates on these barriers and states that they affected the execution of every item in the plan. The most striking were the lack of state land; complex and long planning processes; lack of human resources in the local authorities (specifically engineers); the difficulty of pooling resources and providing suitable funding to match the state budgets; the gap between planning and reality; and the absence of tools for real time monitoring and review (Ministry for Social Equality, 2021c).

These are deep-seated obstacles that require thorough long-term government responses to match the accepted standard in Jewish society; if not addressed, they will continue to hamper effective execution of plans for Arab society. Particularly prominent is the lack of managerial skills in most Arab local authorities, and this must be addressed. In the framework of 922 the Ministry of the Interior worked to develop these skills, with an emphasis on efforts to promote profitable economic projects and the development of independent sources of income. In addition, since most of the programs in the five-year plan were to be implemented primarily by the local authorities, resources were needed to strengthen these authorities’ functional capacity—particularly in the engineering departments—so they could utilize the budgets effectively.

Short term solutions were provided by funding the recruitment of strategic planners in Arab local authorities, as well as projects such as the Muarad venture, which involved a partnership with the Ministry of the Interior, the Finance Ministry, and Joint/Elka. This pioneering venture provides training and placement for managers and leaders of economic development, and full utilization of resources in 44 Arab and Bedouin local municipalities in northern Israel. Yet it appears that even here the achievements stemming from this venture were not complete, and several local authorities were left without a suitable response. One of the main lessons from Resolution 922 is that the local authorities need radical solutions. This challenge joins serious problems of corruption and the exposure of local council heads and senior management to extortion by Arab crime organizations, who see it as a convenient source of income.

Another issue is linked to the degree of support and involvement of the Arab political leadership in the state effort to invest in developing Arab society. Here the picture is not entirely clear, mainly with respect to the involvement or influence of Arab leadership in the formulation of Resolution 922. It was widely assumed that the greater the involvement of Arab leaders, the easier it would be to achieve better awareness and of the plan and its outcomes.

Another important problem is the government’s tendency to divide five-year plans for Arab development among different ministries. Thus, while the Ministry for Social Equality was charged with inter-ministerial responsibility for 922, during the same period other, five-year programs were drawn up and assigned to other ministries. The roots of this problem can be traced to political-coalition considerations, but it increases the difficulty of coordinating between the various plans and creating the correct synchrony and balance during execution. The issue of inter-ministerial coordination is critical and therefore requires renewed thinking about the best way to deal with these divisions.

Internal Obstacles within Arab Society

Apart from the discrimination and neglect that characterized the policies of most Israeli governments toward the Arab sector, there are political and sociocultural features within the society itself that hamper its development and progress. These factors have stood in the way of serious attempts by the government in recent years to bring real change to the Arab situation, by means of well-funded five-year plans. Indeed, the professional literature has extensive reference to these obstacles.

Political Features

Many Arab political leaders and public figures link the national struggle in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to the civilian struggle for equal rights. As such, Arab parties are wont to see Israel as a colonial undemocratic country, support the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel, and encourage converting Israel from the Jewish state into a binational state—in effect, they practice “the politics of conflict” (Smooha, 2021, p. 4). For years this prevented the inclusion of Arab parties in government coalitions and the decision making process, and even decisions affecting Arab society. From this position, they had little scope to deal with the fundamental problems of the Arabs.

This politics of conflict was perceived by the Jewish public as identification with the Palestinian enemy and as seeking to deny the Jewish character of the state. It is understood as a lack of loyalty to the state, to the extent that Arabs are even seen as a fifth column, and this contributes to the hostility between the two societies: on the one hand, there are voices calling to bring down the status of Arabs and limit their civil rights; on the other hand, the unofficial social discrimination against the Arabs grows deeper, as demonstrated by their experiences in daily life.

Sociocultural Features

Most Arab local authorities are characterized by poor management, stemming to a large degree from a low level of organizational culture, internal power structures, and defective financial management. This is compounded by the interference of local clans, leading to unsuitable appointments and the distribution of resources and benefits to political cronies, in the absence of a tradition of public service and good management. All this contributes to the shaky economic situation of the authorities.

Another problem affecting Arab society is the widespread corruption in the management of local authorities, as demonstrated by the State Comptroller’s report. According to a report on tackling crime and violence in Arab society, there is crime directed against people in local government (Prime Minister’s Office, 2020). This corruption interferes with the election of candidates to local government, and functions in practice in various ways (including the use of extortion and violence) to obtain funds from the local authorities (Lehrer, 2020).

Clan ownership of land prevents land deals and is a barrier to development (Abu Shrakia, 2010, pp. 87-92). Private ownership of land, inheritance customs, and the perception of ownership as a value hampers the possibility of solving the lack of land available for construction (Khamaisi, 2006).

Arab society is still patriarchal, and women occupy a low place in the family hierarchy. Over the past decade, more and more Arab women have acquired an education and entered the workforce, but this does not give them equal status with men. The Arab family has yet to undergo the structural changes that will allow women to achieve equality and integrate fully in the workforce (Nijam-Akhtilat et al., 2018). This situation, as well as illegal phenomena such as polygamy, puts the burden of supporting the family on one breadwinner and hinders social development (Fefferman, 2008).

In addition, Arab society is characterized by traditional occupations, mostly physical work, such as construction and agriculture. Even in academic fields, Arabs generally focus on a limited number of areas such as pharmacy and education. Moreover, the Arab business sector consists primarily of small businesses, most of which are commercial businesses or related to construction.

Main Points of the Second Five-Year Plan: Government Resolution 550 (October 2021)

The second five-year plan, called “Long-Term Plan for the Arab Sector—Takadum (progress)” (Ministry for Social Equality, 2021e), was approved by the government on October 24, 2021, with a budget of NIS 30 billion. Concurrent with the new plan for economic and social development, the government also approved a multi-year plan to eradicate crime in Arab society (Prime Minister’s Office, 2021c) with an additional budget of NIS 2.5 billion. The plans are linked in their basic concept of the need for considerable state investment in Arab society. Joining these two plans are parallel five-year plans for Bedouin society (Authority for Bedouin Development and Settlement in the Negev, 2017); the Druze and the Circassians (Prime Minister’s Office, 2021b); East Jerusalem (Prime Minister’s Office, 2018); and cities with mixed Arab and Jewish populations.

The background to the second five-year plan differs from that of 922. In the first plan, the thinking focused mainly on budgets: it was assumed that the state budget at the time did not provide an equal response to different population groups, and in fact isolated Arab society, so that the mechanism for budget allocation had to be entirely overhauled. Accordingly, it was decided that each ministry would allocate part of its budget to Arab society, based on its size relative to the general population. The central idea was that over time, the gaps between the two groups would shrink. In addition, the most important sectors also addressed in Resolution 922 were the allocations for infrastructure (roads, water and sewage, and so on), and education.

The logic behind the formation of the second plan was not purely economic, based on the rationale of the Finance Ministry. The second plan was mainly shaped by the growing understanding among the country’s leadership, including the previous government, that it was important to ensure the continuity and expansion of state investment in Arab society, and to create ongoing investment with the aim of narrowing the gaps between the majority and minority groups. There were also political considerations, linked to the formation of a coalition with the support of the United Arab List.

The second five-year plan gives greater priority to social development, in addition to a wide spectrum of new subjects that were missing from the previous plan—from dealing with disaffected Arab youth through welfare, sport, and culture, to the digital world, and the spread of optical fiber networks to Arab towns in order to improve digital communication access for families, society, and the local economy. In addition, the resolution includes other areas of activity that were not included in previous plans, with the emphasis on the development of growth engines at local authority and regional levels. The resolution seeks to increase productivity in Arab society, and in turn, its contribution to the national economy, with an emphasis on better education and employment options.

The difference in the budgets of the two plans is significant, and should be considered along with the concomitant five-year plans for the Bedouin, Druze, and Circassians, and the plan for dealing with crime and violence in Arab society (Prime Minister’s Office, 2021c). While the budgets for the series of programs accompanying 922 amounted to almost NIS 15 billion, the budgets for the current plans amount to over NIS 32 billion. The current group includes Resolution 550 for NIS 18 billion for the Arab towns included in the plan (excluding the Bedouin and residents of cities with mixed populations); the plan for the Negev Bedouin—some NIS 5 billion; the resolution on tackling crime and violence—about NIS 2.5 billion; and the Druze villages—NIS 6 billion.

Among the main items in the new plan:

- Education is awarded about a third of the entire five-year budget for the second plan (NIS 9.4 billion), primarily in light of the limited success in utilizing the (smaller) budgets in the first plan. Ministry of Education data show that the gaps between education budgets in Arab society and Jewish society and their respective components remained the same, in spite of the nominal increase in investment in Arab society. For example, according to figures published at the end of 2021, the average Jewish student enjoys a budget of NIS 42,000 a year, while his/her Arab counterpart receives only NIS 28,000 (Detel, 2021). In view of the lessons of the first plan, the second plan established the goal of removing the ongoing discrimination in the education system by allocating NIS 6 billion (more than two-thirds of the whole Arab education budget) to funding that was intended to deal directly with the educational gaps. According to this allocation, students from disadvantaged population groups would receive larger budgets than students from stronger groups. Although this amount is unprecedented, it is still not enough to close the annual gap of NIS 14,000 between the budgets allocated to Jewish and Arab students. Rather, it is only enough to reduce the gap by half over a period of five years. In terms of educational content, the new plan for Arab education stresses the importance for Arab students to learn Hebrew, as well as digital literacy at a young age.

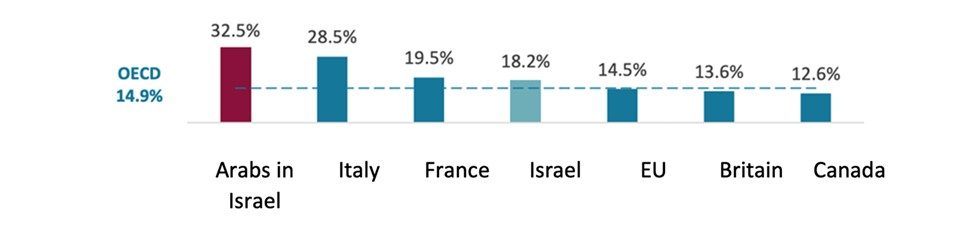

- Unemployed youth in Arab society: This was found to be a critical issue with worrying implications for the country as a whole, and not just the Arab sector. As a result, the government program to tackle violence and crime in Arab society (Resolution 549) refers extensively also to the “soft” components of this challenge. More than 30 percent of Arab youth aged 18-24 are defined as “unemployed,” compared to 18 percent in Jewish society (Ministry for Social Equality, 2021d) (Figure 4). The scope of this problem has spread considerably in recent years, even during the implementation of the first five-year plan. This has widespread implications in many areas, even beyond education and employment, as it impacts rising rates of crime and violence in Arab society and the scope of employment in the economy as a whole. In order to tackle this challenge, the government decided to assign this subject high priority. The second plan addresses it inter alia through the “gap year” program, which has a purpose of giving young Arabs a bridge between secondary school and the next stage in life—employment or higher education. The Ministry for Social Equality is mandated to operate this program in cooperation with other elements. Full details of the government programs for dealing with disaffected youth can be found in the document presenting the recommendations of the inter-ministerial committee on the subject (Ministry for Social Equality, 2021d).

- Housing and development: Resolution 550 deals at length with these matters. Inter alia, it sets a target of marketing 5,000 housing units on state land in 2022 and up to 9,000 units by 2026, by improving the tools for making state land accessible for housing and public institutions. This also applies to areas of removing obstacles to sound urban planning, strengthening local committees and engineering units in local authorities, providing building permits, and developing land and infrastructure. For this purpose, it was decided to establish an implementation and review team. The key to progress is to define criteria for extending residential building rights and control of the practical implementation (Khamaisi, 2019).

- Employment: This area is strongly linked to other areas such as education, infrastructure, and problems stemming from disaffected youth. Therefore, the government adopted the recommendations of the inter-ministerial committee regarding employment (Ministry for Social Equality, 2021d), with an emphasis on the 18 to 35 age group. Increasing digital literacy, strengthening knowledge of Hebrew and English, and increasing the number of Arab students are the main components of the plan to increase the number of employed people in this age group in the medium term. These tools are designed to help young Arabs find jobs requiring more skills and higher pay. The first five-year plan failed to bring about real change in this area, and this is a long process that will not yield immediate results. Therefore, the targets set by the government for 2026 are realistic, representing an employment rate of 75.8 percent among Arab men (aged 25-64), and 46.3 percent among Arab women.

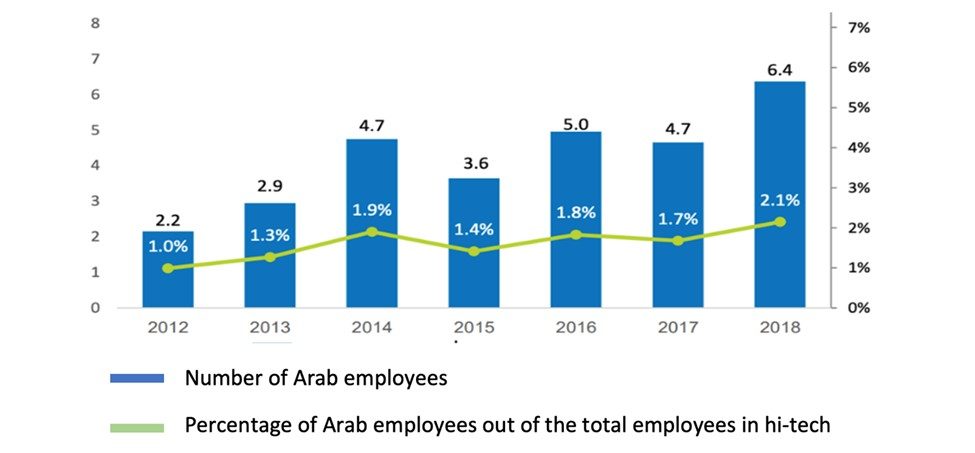

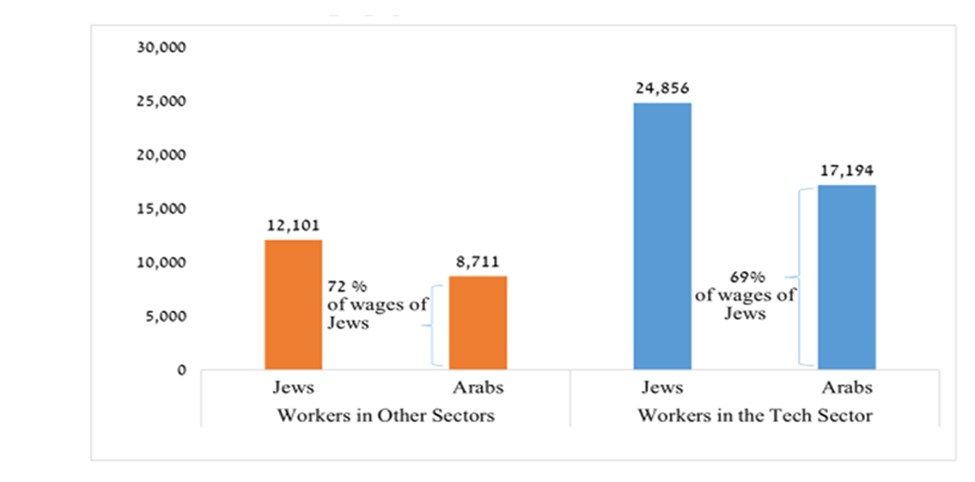

- Industry and hi-tech: The integration of Arab citizens in the hi-tech market is in line with the statement by the head of the Authority for Economic Advancement of Arab Society, that this is a program to develop a growth engine not only for Arab society but for the Israeli economy as a whole (Haimowitz, 2021). In recent years, the hi-tech industry has been a growth engine for the Israeli economy. However, there is a considerable shortage of people able to work in the industry, and one of the important potential reserves for meeting this demand must come from Arab society. Therefore, the adoption of some of the recommendations of the Inter-Ministerial Committee for Promotion of Innovation and Hi-tech in Arab Society, submitted to the government in June 2021, is an important step in this direction (Ministry for Social Equality, 2021a). According to the committee’s figures (relying on the recommendations of the Tsofen organization), only 2.5 percent of all hi-tech employees are Arabs (Figures 5, 6). Increasing the proportion of workers from Arab society will allow hi-tech companies to avoid transferring jobs overseas, while providing high quality employment for Arabs. In the current five-year plan, NIS 600 million is allocated to the integration of Arabs in hi-tech, by means of support for Arab students, technological ventures, scientific enrichment courses, and investment in support infrastructures, including the establishment of another hi-tech industrial zone for Arab society (Bank of Israel, 2021).

From the First Five-Year Plan to the Second

The principal difference between the first five-year-plan, where the main emphasis was on a better and more equitable format for allocating budgets to the Arab sector, particularly in the field of infrastructure, and the second plan, lies in the broader range of areas addressed in the second plan. In particular, the second plan encompasses most of the economic and social areas where there are significant gaps between Arab society and Jewish society, including education, health, welfare, culture, and sport. The defined purpose of the resolution is “to narrow the gaps between [Arab society] and the population as a whole and promote its prosperity and integration in society… with the emphasis on developing employment, both in terms of rate of employment and in quality of employment, and an emphasis on developing infrastructures while maintaining continuity and synchrony with actions taken in the framework of previous resolutions on economic and social development in Arab society" (Prime Minister’s Office, 2021d)ץ

The following primary changes emerge in Resolution 550:

- Twelve government planning teams were established on various topics, including: youth, employment, industrial zones, hi-tech, transportation, and interior. Each team examined the lessons learned from 922, mapped out the needs for the second five-year plan, defined objectives and parameters for each stage in the plan, and specified the responses required in order to achieve the objectives.

- To ensure better coordination and synchrony between the various government plans for the sectors of Arab society, an attempt was made to provide a broad response, with special plans for each sector. For example, there were broad responses in the fields of employment, education, innovation, and hi-tech. The Economic and Social Development Authority worked on this issue to create mechanisms designed to correct the traditional government policy of fragmentation between the sectors. For example, representatives of bodies that are responsible for Bedouin society are currently integrated in the implementation of Plan 550. If the broad responses are successful at the implementation stage, they could bring about a change in the general policy of differentiating between groups in Arab society.

- From the outset, and as the government teams were formed, Arab representatives were more involved in formulating the second five-year plan than they were in in the past. The Arab representatives came from the local authorities and civilian organizations, by arrangement with the committee of local authority heads and with the support of the monitoring committee. This was extremely important because ultimately, the responsibility for receiving the government budgets in many critical areas was in the hands of Arab representatives. As such, without effective coordination with these representatives, it would be significantly more difficult to implement the programs.

- Objectives and metrics were defined for several elements of the plan, apart from a defined budget for each area. For example, the section on water and sewage in 922 stipulates that 40 percent of the water and sewage budgets will be allocated to Arab society, but no specific objectives were defined. In 550, the Water and Sewage Authority was involved in defining the number of houses to be connected to the national water and sewage system. Another example is the subject of housing: although this subject was also central in 922, no clear objectives were defined, while the new plan states the number of housing units to be planned and marketed.

- Strengthening the local authorities, including with regard to human capital, to enable them to fulfill their tasks according to the plan. Inter alia, the following directions for action were defined:

- Increasing the access of the Arab authorities to the government resources intended for them, by improving their organizational and management infrastructure and their ability to execute the programs. Efforts would be made to strengthen their capabilities in the fields of planning, management, and implementation, and to introduce economic projects covering regional clusters of towns and villages (Center for Research and Information, 2019), in collaboration with the Ministry of Economy and Industry, in addition to providing development grants, and encouraging income-yielding projects and growth engines.

- It was decided that no preconditions would be set for local authorities to receive the budgets, contrary to the practice in Resolution 922. For example, in the housing section, 922 defined detailed conditions for local authorities to move from one stage to the next, which made it very hard for them to actually receive the housing budgets due to them. In 550 in was stated that ministries would not set conditions for the transfer of budgets to the local authorities, but rather, would give the professional elements space to maneuver and use their judgment and work in collaboration with the Economic and Social Development Authority.

- Another way of facilitating implementation of the programs within Arab society is to bypass the local authorities and use state companies. For example, regarding roads, it was decided that the Ministry of Transport would execute the five-year plan’s projects by means of the Netivei Ayalon company (Sadeh & Broitman, 2022).

- A special team was set up in the Ministry of the Interior (Ministry of the Interior, 2022) to focus on government handling of local authority tenders if there was a high risk of criminal elements interfering and taking control. The aims defined for this team were to examine how funds are transferred to the authorities for the economic plan; examine the changes required in the conduct of local authority tenders; focus the ministry’s ability to review the development activities of the local authorities. Short-term recommendations submitted in March 2021 included keeping criminal elements away from tenders and combat threats against local authority heads using external mechanisms such as government companies, regional clusters, the Local Government Economic Services Ltd., and other similar mechanisms.

- The government mechanism for coordinated implementation of the plan should be based on the following arrangements:

- A ministerial committee on Arab social affairs headed by the Prime Minister to outline policy and decide on disagreements between ministries.

- An inter-ministerial coordination committee headed by the government secretary, to deal with synchronicity between government resolutions and decide on disagreements between ministries. An example is the question of coordinating the elements of Resolution 549 on the struggle against crime and violence in Arab society, with Resolution 550 on reducing the gaps in Arab society.

- A permanent small committee with representatives of the Prime Minister’s Office, the Budget Division, and the Economic Development Authority in the Ministry for Social Equality:

- The Committee has the power to divert budgets between ministries as necessary.

- It will approve the annual work plan of each of the government ministries, to be presented at the start of each year (in contrast to 922, in which ministries presented their activities during each year at the end of the year).

- It will coordinate the detailed information about all the work programs in all the ministries to facilitate close supervision of implementation.

Conclusion and Systemic Recommendations

There are various ways of assessing the government’s efforts to improve the socioeconomic situation of Arab society in Israel. There is no doubt that the fundamental turning point, reflected in the preparation of heavily funded five-year plans for this purpose, is highly laudable and nothing less than a paradigm shift from its previous policies—even though the initial strategy was limited, at least at the beginning, and based largely on economic elements seeking to raise the productivity of Arab citizens. Since then, the designers of the five-year plan, who also want to reduce economic and social gaps, have become more aware of the need for maximum integration of the Arabs in the fabric of Israeli life (Special Committee on Arab Social Affairs, 2021).

When assessing the implementation of the plans, principal questions arise. First, how many of the stated projects were actually completed, how many were partially implemented, and how many were not implemented at all. A summary by the Minorities Economic Development Authority stated that half of the 922 projects were completed. By contrast, the Citizen Empowerment Center found that one-fifth of the 63 items and sub-items in the five-year plan were not implemented, only 27 items were completed, and 22 were partially implemented (Citizen Empowerment Center, 2021). This metric indicates general trends in the scope of the success, but does not give a full or accurate picture of actual performance in the field, especially since in the case of 922 the general success rate is not high, to say the least.

More challenging is the second question, namely, how much of the total five-year budget was actually used. This calculation is complicated, if even possible, because there was no official report in advance of the scope and duration of the plan (announcements varied wildly between 6 and 15 billion shekels for the whole period). The summary document from the Minorities Economic Development Authority in the Ministry for Social Equality (Ministry for Social Equality, 2021c) indicates that some of the lacking performance was due to partial utilization of budgets. For example, a report submitted on June 21, 2021 to the Knesset Committee on Arab Social Affairs stated that of NIS 10.7 billion originally allocated, NIS 9.7 billion were actually distributed, of which slightly more than NIS 6 billion were used. This partial use was mainly due to the many obstacles mentioned above, and to the fact that some budgets were allocated to infrastructure projects and spread over several years. Therefore, from the perspective of resource allocation, it is impossible to give an accurate assessment of the success of the first five-year plan, either as an overall national input or as an investment by areas of development or by government ministry.

The most important but most complicated question is what tangible change the allocation of these budgets generated in the socioeconomic standing of Arabs in Israel. No official figures have yet been published to decide the success of the first plan based on official data. A survey in Arabic in July 2021 by the Israeli Democracy Institute and The Marker questioned how Arab citizens perceive their situation in recent years. i.e., during the years of the first five-year plan (Feldman, 2021). The limitations of the survey for assessing the five-year plan and its various items must be considered, but the overall picture that emerges from the survey is that for the most important indicators (except opportunities for education), the Arabs in Israel believe that their situation has deteriorated far more than it has improved (Table 6).

Table 6: The situation of Arabs in Israel, from their perspective, July 2021 (in percent)

| Deteriorated | Improved | Unchanged | |

| Political influence | 42 | 22 | 30 |

| Economic welfare | 46 | 17 | 33 |

| Employment opportunities | 41 | 25 | 29 |

| Educational options | 20 | 38 | 35 |

| Status in Israeli society | 46 | 18 | 30 |

Source: INSS analysis, based on Feldman’s article, 2021

This trend is corroborated by a survey conducted by the Konrad Adenauer Center at the Dayan Center of Tel Aviv University in July 2022, which showed that 40.9 percent of participants believed that the situation of the Arab population following the Bennett-Lapid government was worse than before, while 44 percent believed that the situation was unchanged. Only 13 percent thought there had been an improvement in the situation of the Arab population (Rudnitzky, 2022).

Assuming these figures reflect the views of the Arab public in Israel, Resolution 922 did not create a feeling of positive change among Israel’s Arab citizens. The cognitive aspect is very important since it reflects the attitude of the Arab public not only to their situation in the country, but also toward with respect to the impact of the state investment. This joins a significant development, namely, the sharp increase in crime and violence in Arab society, which occurred during the years of the first five-year plan—even though the plan aimed to create the conditions for economic development and a reduction in crime and violence.

It appears that the government has addressed the cognitive element and decided (March 24, 2022) to address it, through the Minorities Economic Development Authority, and embarked on a campaign of explaining and branding the Takadum plan (Prime Minister’s Office, 2022). The goal of the campaign is to strengthen the confidence among the Arab public in the activities of government ministries by instilling awareness of the responses provided by the five-year plans. Thus far this effort is in its very early stages, and it is too early to comment on its success or failure. In addition, the government would do well to market such moves not only in Arab society, but also to the general public, which is not sufficiently aware of what is being done in these important areas.

Some encouragement is provided by the emphases in the second plan, based partly on the lessons derived from the incomplete implementation of the first plan. The government resolution guides the ongoing work of the relevant ministries in order to achieve successful implementation of all elements of the plan. At this stage, it is not clear which detailed plans have already been approved or whether their implementation has actually begun. The transition from Resolution 922 to Resolution 550 will not be smooth, and will require complex work by some of the ministries before they can start implementing the projects of the second five-year plan.

Against this background, what follows are selected systemic recommendations—some of which echo items in the government resolution—to shape the ongoing planning process and achieve effective execution of Government Resolution 550:

- Five-year plans for the development of Arab society do more than correct an aberration, neglect, and mistreatment. The rapid narrowing of gaps and promotion of equality between Jews and Arabs is a central pillar required for achieving national stability and prosperity. Five-year plans are essential for this purpose, but they must be designed in order to achieve their defined goals within realistic time scales, as quickly as possible, with optimal effectiveness and broad public acceptance.

- This time the government has decided on a tighter system of ensuring proper execution of the plan, but the work is in the hands of various ministries, agencies, and Arab local authorities. This is a bureaucratic-political Achilles’ heel, as was evident the first plan. The permanent select committee must have clear and binding powers from the Prime Minister and the ministers’ committee over the Prime Minister, to ensure that the progress of implementation will be monitored as fully and accurately as possible, in all its aspects, with public disclosure of any delays and defects when discovered, so that rapid solutions can be found.

- Resolution 550 defines quantitative objectives in some areas, and stipulates monitoring of activities and achievements (or delays). It is highly desirable that progress based on defined objectives is monitored and reported periodically (preferably quarterly), to prevent the accumulation of delays. In addition, there should be a report at least every six months to the Knesset Committee and an annual detailed report to the public from the Minorities Economic Development Authority.

- There should be optimum coordination and synchronization between the various five-year plans, some of which overlap, or are closely linked. It was decided that government responsibility for this matter, and for monitoring the implementation of the plans, should be in the hands of the Economic Development Authority in the Ministry for Social Equality, by means of the permanent committee set up for this purpose. However, previous experience shows that the Authority does not necessarily have sufficient strength, either political or organizational, to stand up to the ministries that are responsible for planning and executing parts of the plans. This is a serious obstacle, linked to the government’s organizational structure. There is a need for renewed thinking by the Ministers’ Committee on Arab Society Affairs, headed by the Prime Minister, to formulate a better response to these issues. The best way might be to place the responsibility for all the tasks relating to Arab society on one ministry. If this is not politically practical, it would be advisable to significantly reinforce the status, powers, resources, and professional abilities of the Economic Development Authority in the Ministry for Social Equality (Prime Minister’s Office, 2021a), by means of the permanent inter-ministerial committee, to achieve broad, binding implementation of the government resolution (Prime Minister’s Office, 2021d).

- Although there has been important progress in the integration of representatives of Arab society in the planning and implementation of the five-year plans, it is also important for the policy to ensure that the part played by Arab citizens in drawing up and executing the programs reflects their relative share of the population as a whole, and to ensure that the ultimate responsibility for the process rests with the Arab local authorities. Throughout the entire process it is important to ensure and encourage the delegation of greater responsibility for managing the projects to Arab society and its representatives, particularly those in the field. Benchmarks for implementing this policy can and must be determined.

- The question of the ability of the Arab local authorities to deal with the tasks and utilize the budgets on projects within their jurisdiction is very familiar, still relevant, and is a central aspect for government examination. Various solutions proposed recently (in March 2022 by a special team established for this issue and coordinated by the Ministry of the Interior), such as the transfer of budgets through regional clusters or government companies, are still not fully implemented and are therefore not a response to this challenge. Moreover, the weaker Arab authorities and those needing more support from the five-year plan budgets suffer from these problems more than the others, and thus the gap between Arab authorities themselves (such as the Bedouin authorities and those in the north) will continue to grow. There must be an accelerated effort to strengthen the professional abilities of the authorities, with top priority, and provide realistic solutions to this patent obstacle.

- In addition, it is vital to encourage positive relations between the Jewish majority and the Arab minority in the public sphere to facilitate understanding among all sectors and groups that this is an essential mission, not just for the Arab public, but also for the Jewish public and the State of Israel as a whole. One necessary condition is to promote a climate of integration and agreement between Jews and Arabs in all aspects. The inclusion of the United Arab List in the coalition was a critical step in this direction. The country, the political parties, and the media must work to encourage the process, broaden familiarity with the important components, notwithstanding the obstacles, and just as importantly, block the forces opposed to the historical move of integrating the Arab minority into the fabric of Israeli life. This requires constant and energetic promotion and explanation of the programs and their achievements for both the Jewish and Arab publics, in order to reinforce the understanding and acceptance of these plans’ importance.

References

Abu Shrakia, N. (2010). The organizational culture in Arab local authorities and its effect on how they are managed. I n: E. Lavie & A. Rudnitzky (Eds.), The Arabs in Israel: Politics, Elections and Local Government in Arab and Druze Settlements in Israel (pp. 87-92). Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern & African Studies, Tel Aviv University, and the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Israel; Konrad Adenauer Program for Jewish-Arab cooperation. https://bit.ly/3sbMfSk [in Hebrew].

Alizera. R. (2018, June 18). A quarter of a million people fail to buy medication because they have no money. Ynet. https://bit.ly/3NkRBoj [in Hebrew].

Bank of Israel. (2021, October 4). The Arab population in the high-tech sector in Israel. https://bit.ly/3N1y23S [in Hebrew].

Blass, N. (2020). Achievements and gaps in the Israeli education system: Current situation. Taub Center for the Study of Social Policy in Israel. https://bit.ly/3CPY7hV [in Hebrew].

Center for Research and Information. (2019). Regional clusters in Israel. The Knesset. https://bit.ly/3MMvvuj [in Hebrew].

Center for Research and Information (2020a, August 6). Selected data on education in Arab society. The Knesset. https://bit.ly/3W7L1p5 [in Hebrew].

Center for Research and Information (2020b, September 14). Data on employment and pay in Arab society, with the emphasis on the hi-tech industry. The Knesset. https://bit.ly/3EVsl5A [in Hebrew].

Center for Research and Information (2020c, December 29). Issues relating to corruption in local government. The Knesset. https://bit.ly/3yTs92U [in Hebrew].

Center for Research and Information (2021, December 27). Data on Israeli students studying at foreign institutions. The Knesset. https://bit.ly/3eGkQFb [in Hebrew].

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). (2020, July 26). Statistical Yearbook for Israel 2020 – number 71. https://bit.ly/3DcSU52 [in Hebrew].

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). (2022, January 25). Press release: Gaps between Jews and Arabs in quality of life indicators in Israel, 2020. https://bit.ly/3MMNTDw [in Hebrew].

Citizen Empowerment Center. (2021). Monitoring report: Government activity on economic development of minority populations in the years 2016-2020. https://bit.ly/3MMYJtd [in Hebrew].

Council for Higher Education. (2021, October 10). Making higher education accessible to Arab society. https://bit.ly/3Slxl6C [in Hebrew].

Detel, L. (2021, October 4). The investment in religious high school student is the highest in the education system. The Marker. https://bit.ly/3yUEfsE [in Hebrew].

Doctors Only. (2017, December 4). Figures: Infant mortality in the Arab sector is three times higher than in the Jewish sector. https://bit.ly/3Dntwsk [in Hebrew].

Fefferman, B. (2008). Increasing the employment of Israeli Arabs: Is there a chance? Individual responsibility versus government responsibility. Lecture in the Work and Dialogue series: Encounters between Jews and Palestinians in work systems and civil society [in Hebrew].

Feldman, N. (2021, September 14). The unbearable fragility of living together. The Marker. https://bit.ly/3TGUhP3 [in Hebrew].

Hadad Haj Yihyeh, N., Halaila, M., Rodenitzky, A., & Farjeon, B. (2022). Yearbook of Arab Society in Israel for 2021: Abstract. Israeli Democracy Institute. https://bit.ly/3sLCt9X [in Hebrew].

Haimowitz-Raz, M. (2021, December 21). “The five-year plans must bring a growth engine to the State of Israel, not just to Arab society.” Globes. https://bit.ly/3SbW8Kh [in Hebrew].

Innovation Authority. (2019). Report on human capital in the hi-tech industry 2019. https://bit.ly/3DGzJkc [in Hebrew].

Khamaisi, R. (2006). Ownership of land as an obstacle to development, in S. Hasson & M. Karayanni (Eds.), Arabs in Israel: Barriers to Equality (pp. 249-263). Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies. https://bit.ly/3SkiLfE [in Hebrew].

Khamaisi, R. (2019). Planning and development of Arab towns in Israel: New concept of readiness for local authorities and the state. Institute for National Security Studies, Israeli Democracy Institute, Jewish-Arab Center, Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Studies. https://bit.ly/3MJTIkY [in Hebrew].

Krill, Z., & Amariya, N. (2019). Barriers to the integration of the Arab population in the higher education system. Treasury Ministry, Division of the Chief Economist. https://bit.ly/3VLywzp [in Hebrew].

Lavie, E. (2016). Integrating the Arab-Palestinian minority in Israeli society: Time for a strategic change. Institute of National Security Studies and Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Studies. https://bit.ly/3AqNaD8

Levi, A., & Suchi, D. (2018). The causes and consequences of Israeli government resolution 922: A roadmap to accelerate economic inclusion of Arab communities in Israel. Harvard Business school, Mossavar-Rahmani Center. https://bit.ly/3VLHw7m

Ministry for Social Equality. (2021a, June). Recommendations of the inter-ministerial committee on the promotion of innovation and hi-tech in Arab society. https://bit.ly/3VGkXB6 [in Hebrew].

Ministry for Social Equality. (2021b, June 12). Summary of 922 five-year plan for economic development for Arab society. https://bit.ly/3gnAB4j [in Hebrew].

Ministry for Social Equality. (2021c, June 21). Implementation status of government resolution 922: Minorities Economic Development Authority. https://bit.ly/3eRGaY9 [in Hebrew].

Ministry for Social Equality. (2021d, October). Young people in Arab society: Recommendations of the inter-ministerial team. https://bit.ly/3s8xiAm [in Hebrew].

Ministry for Social Equality. (2021e, October 27). Long-term plan for the Arab sector: Takadum تَقَدُّمْ (“progress”). https://bit.ly/3eVa8e1 [in Hebrew].

Minister of the Interior. (2022, May). Summary report on the work of the tenders team. https://bit.ly/3TyZAQk [in Hebrew].

Nijam-Akhtilat, F., Ben Rabi, D., & Sabo-Lal, R. (2018). Principles of work and intervention adjusted for Arab society in welfare and treatment services in Israel, pp. 11-13. Myers-JDC-Brookdale, Engelberg Center for Children & Youth. https://bit.ly/3gpOgI3 [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office. (2015, December 31). Government activity for economic development of minority populations in the years 2016-2020. Government resolution no. 922 of 30.12.2015. https://bit.ly/2lRUK6k [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office. (2016, June 19). Objectives in the field of education in minority populations. Government resolution no. 1560 of 19.06.2016. https://bit.ly/3gb5Dft [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office. (2018, May 13). Reduction of socioeconomic gaps and economic development in East Jerusalem. Government resolution no. 3790 of 13.05.2018. https://bit.ly/3TupqFo [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office. (2020, July). Recommendation of the committee of DGs for tackling crime and violence in Arab society: Summary policy document. https://bit.ly/3s8AH27 [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office. (2021a, July 25). Promoting socioeconomic development in Arab society: Government resolution no. 169 of 25.07.2021. https://bit.ly/3Tjjzmv [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office (2021b, August 1). Promoting a five-year plan for the Druze and Circassian communities. Government Resolution no. 291 of 01.08.2021. https://bit.ly/3yVwZwD [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office (2021c, 24 August). Plan for tackling crime and violence in Arab society 2022-2026. Government Resolution no. 549 of 24.10.2021. https://bit.ly/3VXn4R5 [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office (2021d, October 24). Economic plan for reducing gaps in Arab society by 2026. Government Resolution no. 550 of 24.10.2021. https://bit.ly/3VzO7BQ [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office. (2022, March 24). Promoting a campaign of explaining and branding the Takdum plan for socioeconomic development in Arab society. https://bit.ly/3eJcn41 [in Hebrew].

Rudnitzky, A. (2022, October 25). In-depth study of the Arab public before the elections to the Knesset. Konrad Adenauer Program for Jewish-Arab Cooperation. https://bit.ly/3TYeT5f [in Hebrew].

Sadeh, Y., & Broitman, D. (2022, February 14). Model for budgeting infrastructures in Arab society created a planning “logjam.” Calcalist. https://bit.ly/3EXCJK5 [in Hebrew].

Smooha, S. (2021). Elements and implications of including an Arab party in the coalition: Is this a revolutionary and sustainable change? Hedim (أصداء), 9. https://bit.ly/3CReAT1 [in Hebrew].

Special Committee on Arab Social Affairs. (2021, June 23). The five-year plan for economic investment in the Arab sector 922: About 90% of the money was allocated—only 62% of the budget was utilized. The Knesset. https://bit.ly/3yUEwvG [in Hebrew].

Tehawkho, M. (2019, December). Arab society as an engine of growth in the Israeli economy— Policy paper. Aaron Institute for Economic Policy, Herzliya Interdisciplinary Center, https://bit.ly/3TM23Y6 [in Hebrew].

________________

[1] The document is based on the ongoing professional collaboration between the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) and the Minorities Economic Development Authority in the Ministry of Social Equality. The Authority was established in 2007 by virtue of Government Resolution 1204 of February 15, 2007. Its main aims are to work for the realization of the economic potential of minorities, to encourage their economic and business activity, and to promote their integration in Israeli society and the Israeli economy. In this spirit, the Authority works, inter alia, to strengthen the economic base of this population and create growth engines to reduce social and economic gaps.

[2] These figures do not include the allocation of NIS 5.8 billion and the scope of Education Ministry implementation in the area of formal education (see above), for which we have no data.

[3] The Ryan Centers are a government initiative to encourage and heighten Arab employment in Israeli society.