Strategic Assessment

Taiwan—with the complicated and charged relationships surrounding it—is considered one of the most prominent areas of contention in the global arena. As the competition or rivalry between the two main global superpowers, the United States and China, escalates in the Asian or Indo-Pacific region, the tension surrounding the Taiwan issue heightens, the rhetoric intensifies, and the parties’ actions create a new status quo that at any moment threatens to give way to actual warfare. This article examines the development of the trilateral China-Taiwan-US relationship since the Democratic Progressive Party’s return to power in Taiwan in 2016, the ways this relationship has deteriorated during this period, and the possible reasons for this. The article focuses on the processes that took place from the visit of Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi’s to Taiwan in August 2022 until a new president took office in Taiwan in May 2024—President Lai, also from the DPP. These processes are referred to as the Fourth Taiwan Strait Crisis, which is ongoing.

Keywords: China, Taiwan, United States, Taiwan Strait Crisis, Communist Party, Kuomintang, DPP

Introduction

The year 2016 was characterized by the culmination of several processes, both internal to China, Taiwan, and the United States and at the global level, which changed the course of the trilateral relationship. First, in the United States and Taiwan, it was a presidential election year—at the beginning of the year in Taiwan and toward the end of the year in the United States. The Chinese issue played an important part in both: in Taiwan, on the question of defining its relations with China, and in the United States, as a target of attacks for candidates. At that time, China’s reigning president, Xi Jinping, was in the middle of his first term. He succeeded in strengthening his grip on the party and was defined that year as a “core leader” (领导核心) of China (like Mao, Deng, and Jiang before him). In the first half of his term, China displayed increasing aggressiveness in the global arena, especially in its immediate environs: the East China Sea (in the dispute with Japan over the issue of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands), in the South China Sea, and in Central Asia, including through the Belt and Road Initiative (or One Belt One Road, as it was defined in the initial stages, starting in 2013). This policy was linked to President Xi’s broader vision of “realizing China’s dream of the great national revival of the Chinese people” (实现中华民族伟大复兴中国梦); to the idea of the “new era” (新时代) expressing the worldview of the Communist Party of China in recent years (especially since 2017); and to “Xi Jinping’s thought on socialism with Chinese characteristics for the new era” (习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想) more broadly (China Daily, 2017). Together these three elements were intended to further a paradigm shift in the history of modern China and the world as a whole: a qualitative and quantitative change in China’s successes and a change in China’s global standing, assuming the central and dominant place—that it believes it deserves—on the world stage, since President Xi Jinping’s rise to power (Dai & Luqiu, 2022; Holbig, 2018; Insisa, 2021; Wei et. al., 2023).[1] China’s relationships with its close neighbors were supposed to change accordingly and to express China’s new dominance.

The Taiwanese political system was in turmoil ahead of the 2016 elections. The two main parties in contention then (and now) were the Kuomintang (the “nation’s party” or KMT) and the DPP (Democratic Progressive Party). The main disagreements between them centered on a variety of internal and external issues. In domestic and economic policy, the DPP had more of a left-wing, socialist tendency, a more liberal approach toward social issues (such as same-sex marriage) and a more lenient constitutional approach that focuses on rehabilitating criminals rather than punishment. In contrast, the Kuomintang has been considered more conservative, favoring a freer and more capitalist economy with less taxation. More importantly for our purposes, the Kuomintang, certainly during its years in power until 2016, accepted the One China principle or policy in accordance with the 1992 Consensus with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and sought to strengthen connections with the PRC. The DPP, in contrast, advocates a distinct Taiwanese identity, decentralizing economic relations and reducing dependence on the PRC, and the idea, intentionally presented somewhat vaguely, that Taiwan has been a sovereign state for some time (so there is no need to declare “independence”). In addition to these two parties, the TPP (Taiwan People’s Party) emerged in 2019. It is ideologically closer to the Kuomintang but presents itself as more pragmatic. Given that the public sees it as detached from the Kuomintang’s historic connection to the decades of dictatorial and sometimes violent rule, this gives it a certain advantage over the Kuomintang, but during the 2016 elections, the TPP had not yet been established

The “sunflower protests,” which reached a climax in 2014, strongly criticized the Kuomintang’s conciliatory policy toward the PRC. It became a significant political force, and in the January 2016 elections, the DPP won a majority in the legislature as well as the presidency, and Tsai Ing-wen became president of Taiwan. It appeared that the question of Taiwanese “independence” was back on the table, although officially, before the elections, the DPP declared that it was not addressing it. Shortly before the elections, in November 2015, China’s president and Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou met in Singapore after a series of official meetings in China and Taiwan between senior officials from China’s Taiwan Affairs Office and Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council in 2014 (which were preceded by an unofficial meeting between them in Bali in 2013). It appeared that relations between the two countries could progress along a positive trajectory. This only reinforced the significance of the Kuomintang’s fall and the DPP’s subsequent rise (Insisa, 2016). During Barack Obama’s final year as U.S president, efforts to establish the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) succeeded.[2] On one hand, it seemed that the United States was intensifying its attempts to confront China as part of the Pivot to Asia (President Obama’s policy, mainly from 2011, of transferring the center of gravity of American foreign policy to Asia). Yet on the other hand, China was very displeased with this and would likely thus strengthen its attempts to confront these actions (deLisle, 2018; Tsai & Liu, 2017). So while it seemed that the relationship between China and Taiwan was improving, despite various challenges, the year 2016 was a watershed on this issue, and in certain senses, the relationship began to deteriorate from that point on. In this article, I seek to examine the dynamics of China-Taiwan-US relations since 2016 and to explain the reasons for these dynamics, to assess elements of continuity after this year, and identify the main trends in these relations, particularly from 2022 (the beginning of the Fourth Taiwan Strait Crisis) until Taiwanese President William Lai, also from the DPP, took office in May 2024.

Continuity and Change Since May 2016

In December 2016, a symbolic event marked a shift in the trilateral relationship. President Tsai called President-elect Trump to congratulate him. For over three decades, the presidents of the United States and Taiwan had not spoken, certainly not officially, but Donald Trump received the call, and the two reportedly spoke for about ten minutes. Intentionally or not, this phone call signaled to the PRC that a new era may have begun in which the One China policy is no longer accepted. The Obama administration made sure to declare immediately afterward that the United States was continuing the One China policy, and the response from China was quite tepid and mainly blamed Taiwan for the “ruse,” but the phone call’s symbolism was not lost on any of them (deLisle, 2018), and it was not just symbolic. For example, in Obama’s second term, there were almost no US arms sales to Taiwan (except in 2015), but already in the first year of Trump’s presidency, the arms deals between the countries were renewed and even increased (Dickey, 2019).[3]

Furthermore, the general worsening of relations between the United States and China, with the relationship defined as “strategic competition” at the end of 2017, and the “trade war” that arrived soon afterward, were not, of course, confined to the bilateral sphere; they had global implications, including on Taiwan. Thus, the more the United States emphasized its shared values with democratic countries and stressed the problematic nature of the PRC’s form of government, with an emphasis on the CCP (the Chinese Communist Party), so calls in the United States to strengthen its relations with Taiwan in order to firmly stand up to China grew. The Taiwanese DPP in turn also aspired to strengthen relations with the United States while emphasizing shared values, democracy, and more, further widening the gap between the PRC and Taiwan (Insisa, 2021).

Official relations between the PRC and Taiwan hit a snag again, although, as in the past, their economic relations continued to advance and even reached new heights. Taiwanese public support for the DPP and President Tsai decreased, irrespective of the Chinese issue, due to internal issues and especially because the economic situation had not improved as they had hoped. As the president’s four-year term progressed, the polls in Taiwan indicated a return to support for the Kuomintang. But throughout 2019, in the lead-up to the January 2020 elections in Taiwan, this trend changed and support for the president returned, in no small part due to events related to the PRC. During this period, a huge wave of protests arose in Hong Kong, triggered by a new extradition law being discussed (which allowed Hong Kong citizens to be quickly and easily extradited to mainland China), along with closer judicial cooperation. However, the protests were based on deeper reasons than the law itself (which was not ultimately passed at that time), in particular the weakening of the fundamental separation between the legal systems of China and Hong Kong, as well as the democratic system of Hong Kong in general—a trend that began years before.

This point, along with the growing protests and their violent suppression, demonstrated to Taiwan (and others) that the solution reached on the Hong Kong issue—“one country, two systems” (一国两制)—is unworkable. This solution, which began in practice after the UK handed Hong Kong to the PRC in 1997, was sometimes seen as a model that might also enable Taiwan to peacefully integrate within the framework of the PRC: one country (the PRC), in which different governmental, economic, and legislative systems can live side by side—mainland China, and beside it (that is, under it) “special administrative regions” (SAR) with different systems. China’s forceful actions in Hong Kong and its offensive diplomacy (which came to be called “wolf warrior diplomacy”) convinced the Taiwanese that such a system is not a legitimate option for them and prompted them to protest in solidarity with Hong Kong’s residents. Taiwan’s president leveraged this and rode the wave of protests to a second term in 2020, while the Kuomintang—which over time had sought to promote relations with the PRC—had difficulty responding to the protesters’ claims (Brown & Churchman, 2019; Insisa, 2019).

While it is obvious that the primary issue on the agenda is “unification” (统一, or “reunification”), it is important to understand the main controversies included under this general title, especially since 2016. On the part of the PRC, several primary demands are seen or presented as conditions:

- Taiwanese acceptance of the 1992 Consensus (九二共识), which includes the One China principle;

- The demand for Taiwan’s complete rejection of the idea of “Taiwanese independence” (台独);

- Taiwanese acceptance of the principle of “one country, two systems” as the necessary action basis for unification;

- A rejection of any “external influence or involvement” (外部势力干涉) in their relations, referring first and foremost to American involvement, of course.

In this context, Taiwan’s conduct under President Tsai has been ambiguous: The president accepted the “historic fact” that there were discussions in 1992, but not the consensus (on the One China principle) as China presents it, and took from the 1992 understandings mainly the idea of continued discussions in the spirit of peace and good will. While she has not spoken unequivocally of Taiwanese independence, the President has claimed the separate existence of Taiwan and repeatedly emphasized its democratic system, which is fundamentally different from the Chinese system, and thus also the assumption that any decision on Taiwan’s fate would be in the hands of the Taiwanese people. The principle of “one country, two systems” was rejected, certainly after 2019; and Taiwan under Tsai also sought to strengthen its relations with the United States (and with other “like-minded” democratic countries), as well as to strengthen Taiwan’s international standing, for example through participation in a variety of international institutions (Insisa, 2019). Hence, not only has the question of unification remained unanswered, the very ability to engage in negotiations or discussions about the future of relations has faded, while in China, voices claiming that Taiwan is striving for “independence,” “cultural separation” (文化去中), “economic distancing” (经济排中), “diplomatic opposition” (外交抗中), and “the use of democracy to repel China” (民主拒中) have grown louder, prompting claims that the use of military force is the only way to implement unification (Zhao, 2023).

Moreover, in parallel with President Tsai and her party coming to power, since 2016, not only has the PRC escalated its tone toward Taiwan, it has also held military exercises close to the island almost every year. A significant portion of them began after “provocations,” in the PRC’s view, by Taiwan or its ally, the United States. A few days after Tsai was elected president in January 2016, the Chinese military held live firing drills and also mock landing exercises to practice taking over “some” island. The new president’s inauguration was also accompanied by Chinese military exercises in the sector close to Taiwan, sending a clear message to the new president and Taiwan as a whole (Denyer, 2016). In addition, during Tsai’s first term, the PRC continued to increase its military presence (mainly the navy and air force) in both the East China Sea around Taiwan and the South China Sea (south of Taiwan) and increased its sorties and demands in the sector of the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands north of Taiwan—islands controlled by Japan but claimed by both the PRC and Taiwan (Xin, 2020). The fact that President Tsai visited the United States several times during her first term (until the COVID-19 pandemic) did not help ease the tensions either.

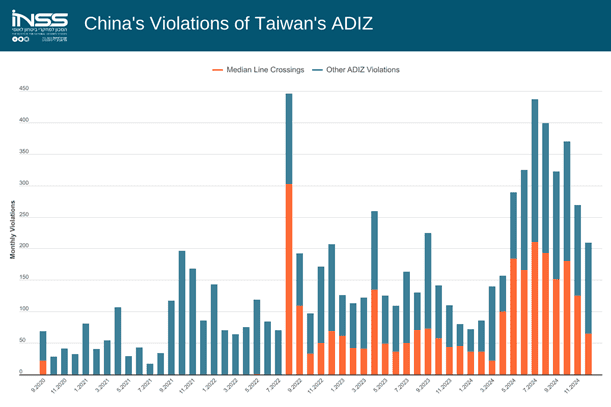

With respect to the PRC’s air sorties, it is important to remember that at the end of 2013, China unilaterally declared a new air defense identification zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea. This occurred after a worsening of the territorial dispute between China and Japan (primarily but not only) about sovereignty over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, and the new ADIZ created a dangerous overlap between the ADIZs of China, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea (Trent, 2020).[4]

Figure 1: ADIZ overlaps in East Asia | Source: Ebbighausen, 2021

Gradually, and especially since 2016, China increased its air operations in the new area. Thus, in 2016 and 2017, it seemed that most of China’s military activity in the maritime and air sector focused mainly on the South China Sea (largely due to the discussions and later decision by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague in favor of the Philippines in its conflict with China there) and around the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands. But China’s air operations in the area close to Taiwan also increased, especially flights by H-6K strategic bombers, which were greatly augmented, including encircling the island in an unprecedented manner. These encirclements, which came to be called “island encirclement patrols” (绕岛巡航) in 2017 in reference to the encirclement flights around the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, also entered the 2019 white paper for China’s National Defense in the New Era (新时代的中国国防), and were described as part of China’s readiness to “protect the country’s unity” (捍卫国家统一) at sea and in the air and as “a serious warning to the divisive ‘Taiwan independence’ forces” (对“台独”分裂势力发出严正警告) (Guowuyuan xinwen bangongshi, 2019). On several occasions, the bombers were accompanied by airborne warnings and control, electronic warfare, anti-submarine, and intelligence gathering aircrafts—various models of Tupolev 154, KJ-500, Y-8, and Y-9; by aerial refueling aircrafts; and by fighters such as the J-10, J-11, or Sukhoi-30 (Grossman et al., 2018; Trent, 2020).

Taiwan responded with military drills of its own, while the United States increased its defense budget for US Navy visits to Taiwan. The increase in Chinese flights around Taiwan in the summer of 2017 may be connected to the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, which was held in October of that year—a central event in Chinese politics. In this case, Xi Jinping’s term as the party’s General Secretary was about to be extended by five years, so demonstrating a strong stance and assertiveness in the Taiwanese sector were seen as strengthening his position. In addition, this conduct may also be connected to the comprehensive reform conducted in the Chinese military in 2015 and 2016, and the desire or need of the new branches and commands to conduct training and demonstrate operational readiness (Wuthnow, 2017).

However, in the 2010s, the vast majority of Chinese incursions into ADIZs in East Asia were clearly and overwhelmingly into Japan’s air identification zone. According to estimates, in that decade Chinese Air Force aircraft penetrated the Japanese zone more than 3,000 times and into the South Korean Zone (starting in 2016) more than 300 times. Despite the air exercises around Taiwan, along with extensive exercises by the Chinese Navy (and a change to a civilian airway so that it passed closer to the median line), only in 2019 did Chinese Air Force aircraft begin to consistently enter the Taiwanese ADIZ, and these incursions became slightly more frequent. But more concerning from the Taiwanese and American perspective was that at this stage, several flights (mainly of fighters such as J-11 and later J-16) intentionally crossed the strait’s median line for the first time in decades, with Chinese officials denying the existence of such a line (Trent, 2020).

Ahead of the Taiwanese presidential elections in January 2020, the frequency of the flights increased, and after Tsai’s re-election, incursions by Chinese aircraft became increasingly routine. Chinese Navy ships also penetrated Taiwan’s maritime zone, including what appeared to be a show of force by Chinese aircraft carriers, and on more than one occasion, “militias” of Chinese civilian “fishing boats” have also demonstrated heightened activity around Taiwan (Dobias, 2024). Not only have Taiwan’s elections led to increased incursions, mainly into the ADIZ but sometimes also crossing the median line; but visits by American officials such as Alex Azar (US Secretary of Health and Human Services) in August 2020 and Under Secretary of State Keith Krach in September 2020, plus multiplying arms deals that the United States continued to approve for Taiwan, also served as a reason or an excuse for such sorties. Thus, the old status quo surrounding Taiwan has changed dramatically, especially since the end of 2020, and a new status quo has emerged in which sorties, aircraft incursions, median line crossings, and increased Chinese maritime activity (military and civilian) have become routine (Ebbighausen, 2021).

Figure 2: Air incursions into Taiwan’s ADIZ by the Chinese military

Source: Brown & Lewis, n.d.

Part of the explanation for the increase in China’s threat policy is also related to the United States’ growing involvement in the Indo-Pacific region: reviving the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad: the United States, Japan, India, and Australia) starting in 2017, but with greater intensity during the Biden administration; the military alliance between the United States, the UK, and Australia (AUKUS) in 2021 (with recent rounds of talks on adding Japan and South Korea); and the attempt to establish a significant economic alliance (IPEF) in 2022, which is still in the process of being formed (Koga, 2024).[5] All of these, in addition to increasing American involvement in the Philippines, have contributed to a sense within the PRC of being under siege. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic, which initially seemed like it might help improve relations (through medical cooperation) between the PRC and Taiwan, also ultimately strained cross-strait relations. While Taiwanese medical staff and researchers were among the first permitted to come to Wuhan right at the beginning of the pandemic, Taiwan’s tremendous success during the pandemic (fewer than ten died of COVID-19) and its loud (and accurate) voice at the World Health Organization led the PRC to see it as a competitor in public opinion, and Taiwan itself to seek more of a presence in the world arena and international organizations, with greater international legitimacy (Cabestan, 2022; Zhang & Savage, 2020).

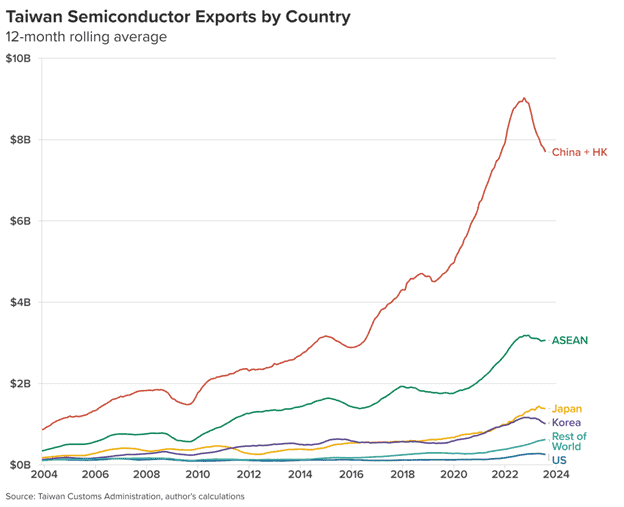

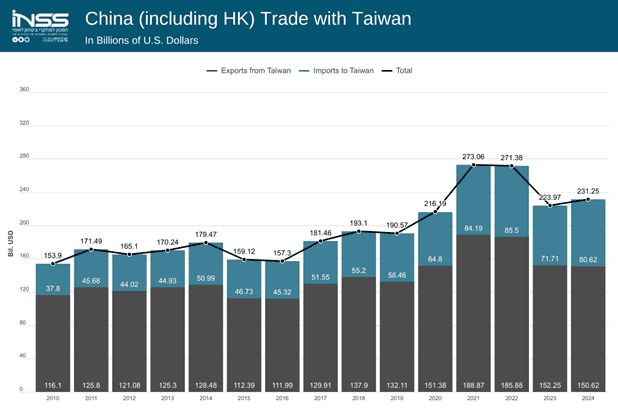

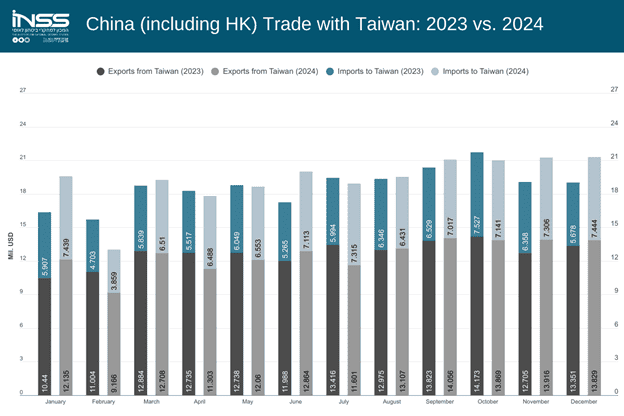

Despite all these tensions, during Tsai Ing-wen’s terms, the volume of trade between China and Taiwan grew dramatically. The volume of Taiwanese exports to China is four times that of imports from China, with semiconductors as the “star” of Taiwanese exports. Investment, especially by Taiwan in China, also grew dramatically during this period (although it somewhat declined in more recent years). In other words, in the past eight years, we have witnessed two opposing trends: on one hand, an intensification of the harsh rhetoric across the strait and of related military measures, with economic, cyber, and security threats from the Chinese side; and on the other hand, the strengthening of economic and business relations between the two sides (Liu, 2022). For years, before the COVID-19 pandemic, it seemed that tourism and cultural relations were also improving. The strengthening of relations was also accompanied by the question of Taiwanese (and, to a certain extent, Chinese) dependence created by these relations (Mark & Graham, 2023).However, almost three years of a zero-COVID policy in China, and a certain tendency toward detachment from the outside world, ultimately reversed this trend—at least for now.

Figure 3: Volume of semiconductor exports from Taiwan by country/region

Source: Atlantic Council (Mark & Graham, 2023)

Figure 4: Trade between Taiwan and China (including Hong Kong) according to Taiwan customs data

Data from: Mainland Affairs Council, Ministry of Finance, Republic of China

Another issue that has significantly increased tensions surrounding Taiwan since 2022 is the war in Ukraine. Immediately after the Russian invasion, an increasing number of voices began suggesting that the PRC sees the war in Ukraine as a kind of trial run ahead of a near-future campaign against Taiwan, that China is assessing not only the military aspects of the campaign but also the ways in which the world responds to it, and that China would “exploit” the global attention on Ukraine to pursue military action against Taiwan (Köckritz, 2023). So far, these forecasts have proven wrong. China, of course, has assessed and is assessing this campaign in the Taiwanese context too, but it is very important to China to differentiate Ukraine entirely from Taiwan (more on this below). Also, Russia’s failure to succeed in Ukraine may have discouraged China from similar activity, together with a lack of desire to invade Taiwan thus far, regardless of the Russia-Ukraine war. However, during the fighting and perhaps due to the loud and concerned voices regarding Taiwan, then-Speaker of the US House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi decided to visit the island.

And Then Pelosi Came

Pelosi’s visit was the highest-ranking American visit since Newt Gingrich’s visit to the island about 25 years earlier, in 1997. He was the speaker of the US House of Representatives, and he came to the island shortly after the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis (1995-1996). While the Biden administration expressed discomfort about the timing of Pelosi’s visit, it claimed it did not have the authority to prohibit such a trip. And while the administration simultaneously claimed that the visit did not signify a change in American policy—that is, the United States continues to maintain the One China policy—the PRC did not accept this. It is important to analyze the visit at the beginning of August 2022 both based on developments in the international arena and against the backdrop of domestical political conditions, particularly in China and the United States.

First, from the beginning of Joe Biden’s presidency, he emphasized the Indo-Pacific region—from America’s West Coast to East Africa—as a strategic zone of high priority for the United States. In February 2022, shortly before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the American Indo-Pacific Strategy was published (The White House, 2022a, p.2). It opens by quoting the president’s speech a few months earlier: “The future of each of our nations—and indeed the world—depends upon a free and open Indo-Pacific enduring and flourishing in the decades ahead.”

The concept mentioned in this quote, a “free and open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP), developed over the years and was promoted especially by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, particularly in light of China’s increasing dominance in the region. This concept has also been the basis for the development of the Quad in recent years. In the strategy itself, China is explicitly mentioned as a rogue actor, linking the Taiwan issue to the border disputes between China and India and other problematic elements of China’s foreign relations—including tensions with Australia (The White House, 2022a, p. 5):

The PRC is combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological might as it pursues a sphere of influence in the Indo-Pacific and seeks to become the world’s most influential power. The PRC’s coercion and aggression spans the globe, but it is most acute in the Indo-Pacific. From the economic coercion of Australia to the conflict along the Line of Actual Control with India to the growing pressure on Taiwan and bullying of neighbors in the East and South China Seas, our allies and partners in the region bear much of the cost of the PRC’s harmful behavior. In the process, the PRC is also undermining human rights and international law, including freedom of navigation, as well as other principles that have brought stability and prosperity to the Indo-Pacific.

Moreover, the strategy sketches the United States’ main commitments on the Taiwanese issue. Along with the usual statements that the United States continues to adhere to the One China policy, it appears that much of the language aligns with Taiwan’s preferences. In this document, the United States advocates supporting Taiwan, including its military capabilities (for self-defense, of course), all according to the preferences and desires of the “Taiwanese people” (The White House, 2022a, p. 13):

We will also work with partners inside and outside the region to maintain peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait, including by supporting Taiwan’s self-defense capabilities, to ensure an environment in which Taiwan’s future is determined peacefully in accordance with the wishes and best interests of Taiwan’s people. In doing so, our approach remains consistent with our One-China policy and our longstanding commitments under the Taiwan Relations Act, the Three Joint Communiques, and the Six Assurances.

This is while declaring that the United States will protect its own interests, including in the Taiwan Strait, and that it will also promote security in the region in a variety of ways, both militarily and industrially (p. 15). In May of that year, President Biden visited Asia (South Korea and Japan). During the visit, in addition to attempting to strengthen the United States’ strategic relations with the countries he visited (with China always in the background), a meeting of the Quad was held (with South Korea expressing an interest in joining the quadrilateral dialogue), and the IPEF was launched. Furthermore, when President Biden was asked in Tokyo whether the United States would intervene militarily to defend Taiwan, he responded in the affirmative. This response by the president, not for the first time and not for the last time, contradicted the United States’ official policy, the “policy of ambiguity,” according to which the United States does not declare whether it would intervene militarily or not in such a case. Official spokespeople and the president claimed that there was no change in US policy on the Taiwan issue and tried to downplay the unequivocal statements. But from China’s perspective, the statements, along with actions on the ground, certainly indicated a change. The change did not begin in 2022 but years prior, as clarified below. The changes in Japanese defense policy, which were also part of the discussions and declarations in Biden’s visit, with Japan significantly increasing its defense budget (and the areas of investment), the continued American commitment to support Japan’s defense, and all this in the context of Taiwan—all of these contributed to a sense of change from China’s perspective (Aum et al., 2022; Kennedy et al., 2022).

In contrast, we can observe consistency in China’s declarations. The July 2019 white paper—China’s National Defense in the New Era—repeats elements published in the 2005 law on Taiwan regarding China’s territorial integrity, the One China principle, the desire for “peaceful unification,” and alternatively, the fact that China has not abandoned the option of the use of force. However, most of the discussion surrounding Taiwan in the 2019 document relates to the DPP party, which is presented as separatist and promoting “Taiwanese independence,” as well as the involvement of “external forces” that are destabilizing the region (Guowuyuan xinwen bangongshi, 2019).

In August 2022, immediately after Pelosi’s visit, China published another white paper, this time one that focused entirely on the Taiwan Question and China’s Reunification in the New Era (台湾问题与新时代中国统一事业) (Guowuyuan, 2022). Like its predecessors, this document emphasizes that Taiwan is an integral part of the Chinese homeland, that the CCP is taking concrete steps to bring about unification—which they describe as an inevitable process—and that the chances of peaceful unification are actually quite high. The document also presents the DPP and the “external forces” as the instigators of the tension in the region and as those harming peaceful unification (and peace in general) and emphasizes that “the divisiveness of ‘Taiwan independence’ and the plots of external forces must be resolutely crushed” (坚决粉碎“台独”分裂和外来干涉图谋). The document also emphasizes the full commitment of China and the CCP to bringing about the unification, which is presented as a unification of families, as an integral part of China’s “national rejuvenation,” as a core national interest, and as one of China’s decisive processes at this time—that is, in the “new era”—as it is the inevitable result of a “5,000 year” historical process.

The document also notes that despite the DPP’s actions against China and against unification, China has reportedly continued to strengthen ties with Taiwan since 2016. In particular, it highlights the increased economic relations between the PRC and Taiwan in recent decades. At the same time, the document also recognizes the differences that exist between the PRC and Taiwan, for example, socially. It therefore presents the solution of “One Country, Two Systems” (supposedly the solution in Hong Kong) as a feasible and desirable solution. Like its predecessors, this document does not take the option of using force off the table, although it defines its potential use as not against “our compatriots” across the strait, but against separatists and external forces (Guowuyuan, 2022).

Despite the consistency of the “peace-seeking” approach in the documents, in the period between the publishing of the 2019 and 2022 documents the situation on the ground (or rather, in the air) escalated, and, as mentioned above, the incursions into Taiwanese airspace by Chinese aircraft and the various exercises conducted by the Chinese military only increased. Concurrent with the press releases made in Tokyo at the end of May 2022 during President Biden’s visit to Asia, China and Russia conducted an unusual joint air exercise with the participation of strategic bombers over the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea. While they have held many exercises over the years, of course, this one was the first of its kind since the onset of the war in Ukraine, and its execution at a time when the US president was in Japan—whether or not the exercise was planned long in advance—was intended to send a strong message to the United States and its partners: China and its partner Russia will not stand idly by (Bana, 2022; Kennedy et al., 2022). In effect, the more the United States strengthened its alliances in East Asia, it appears to have become clear how few such alliances China itself has. And perhaps, given China’s “alliance deficiency,” it became clear to what extent Russia, however weak, has become increasingly important to China, even if China is ultimately far more important to Russia.

Meanwhile, in the last few years, especially since 2020, and increasing significantly since the middle of 2022, the “trade war” between China and the United States has focused more and more on technology, specifically on semiconductors—“chips” (Brundage, 2023). In addition to the various sanctions, duties, and restrictions that began at the end of Trump’s first term, measures to strengthen the production system and supply chain in this context were introduced at the end of 2021 and in 2022. These efforts were aimed both within the United States and as part of a process of creating technological alliances, especially with countries in East Asia: Japan, South Korea, and, of course, the world chip leader—Taiwan. These actions not only constrained China in this field (with implications for almost every production industry) but were also seen by China as an attempt to forge an anti- Chinese coalition in which Taiwan plays an important role. Thus, an initiative called the TTIC (U.S.-Taiwan Technology Trade and Investment Collaboration) was launched by December 2021, and it continued to gain momentum in 2022 (Keegan & Churchman, 2023). However, it is important to note that as the United States increases the production of chips within its borders or with allies that are not Taiwan, and as the leading chip producers in Taiwan, chiefly TSMC, start to transfer some of their activity outside of Taiwan, this could weaken the idea of the “silicon shield” (Eckl, 2021).[6]

In July 2022, shortly before Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, the United States worked vigorously to prevent the supply of chip production equipment (lithography machines) to China. The technological sanctions and restrictions, the partnerships on this issue with Taiwan and other East Asian countries, and, of course, the broader economic, military, and geostrategic context all significantly increased tensions with China. While Taiwan was not included in the IPEF, a week after its launch, discussions on the U.S.-Taiwan Initiative on Twenty-First Century Trade were announced. This declaration and the talks following it (according to the declarations, it appears that the initiative will be signed soon) made it clear that US-Taiwan relations would continue to advance and would not be negatively affected by Taiwan’s non-inclusion in the IPEF. Of course, from China’s perspective, this was another provocative act (Keegan & Churchmen, 2023). If, in addition to the issues of economics, technology, and geostrategic alliances, we also add the issue of American arms sales to Taiwan—which, according to reports to the US Congress, grew to record levels of over 10 billion dollars in 2022 (and, of course, continued afterward)—the growing tension with China is completely understandable.

Thus, as it became clear that Pelosi was indeed expected to visit Taiwan (the trip was originally planned for April but postponed because Pelosi tested positive for COVID-19), China attempted to send the United States a clear and strong message that it saw such an action as completely unacceptable. The fact that China was celebrating the 95th anniversary of establishing its liberation army did not help calm the situation. Diplomatic entreaties were made, including a phone call between President Xi and President Biden in which the Chinese president said that “those who play with fire will perish by it,” but in vain. In addition, numerous items directly or indirectly related to the visit were disseminated in the Chinese media, such as photographs of nuclear missiles being moved within China or fabricated items about attacks, protests, etc., aimed more at Chinese public opinion than world opinion. While the Biden administration signaled that it was unhappy with the visit at that time, it also made it clear that it could not force Pelosi not to visit Taiwan. China did not accept this statement, and American reiteration of no change in US policy toward Taiwan or regarding the One China policy did not convince China, which may have preferred not to be convinced, in order to present itself as the victim of an irresponsible American administration (Zhao, 2023).

Thus, China announced a series of massive exercises near Taiwan, defining specific areas as no-fly or no-sail zones where the exercises were conducted. On August 4, within less than an hour and a half, China launched 11 short-range ballistic missiles, apparently DF-15B missiles, at marine areas around Taiwan. Four of the missiles passed (at high altitude) over the island itself and struck east of it, and five of them fell in Japan’s exclusive economic zone. During these exercises, artillery shells and short-range rockets were also fired, and a variety of other weapons were utilized, including drones that may have flown over actual Taiwanese areas. All of these operated from several provinces near the Chinese coast, including Fujian, Zhejiang, and apparently Jiangxi, so China’s Eastern Theater Command (東部戰區), which was defined in the military reforms of 2015-2016, could relatively comprehensively practice its capabilities, including the rocket force, the air force, the navy, and more. Civilian boats and ships also took part, whether by helping the blockade or, according to various claims, by providing actual logistical assistance to the navy. The exercises, including incursions by aircraft and ships, continued intensively for several days, and afterward, mainly aircraft incursions continued at a higher rate than in the period before the visit. In addition, there were occasional reports of cyber-attacks in Taiwan, though not on an enormous scale as previously feared, as well as continued Chinese propaganda (Dotson, 2023).

Figure 5: Map of Chinese military activity around Taiwan in the main exercises since Pelosi’s visit

Design: Shay Librowski

Beijing also announced a series of “countermeasures” in response to the visit, including canceling the talks between commanders of the military commands of China and the United States, canceling the Defense Policy Coordination Talks (DPCT), canceling the meetings for discussions on the Military Maritime Consultative Agreement (MMCA), suspending collaborations on illegal immigration, suspending collaborations on legal aid in the field of crime and international crime, suspending collaborations in the war on drugs, and suspending climate change talks (Waijiaobu, 2022).

The United States and many other Western countries emphasized that they had not changed their policy on the Taiwan issue (acceptance of the One China policy) and claimed that China was going too far. The fact that the Chinese actions temporarily paralyzed sea and air traffic around Taiwan demonstrated to the world how effective and problematic a Chinese blockade of the island could be. Moreover, many discussions addressed questions of comparing the strength of the Chinese military forces to those of the United States and its allies in the region, along with various predictions regarding when China will decide to invade Taiwan. It seems that the consensus that emerged was that China has created a new status quo with its increased presence, especially by aircraft penetrating the Taiwanese ADIZ and crossing the median line (Lewis, 2023). In light of the suspension of channels of dialogue with the United States, including the military dialogue, fears increased of an escalation in the East or South China Sea region, especially in the case of a potential, unplanned local incident.

Between Pelosi’s Visit and the 2024 US Presidential Elections

It is important to remember that for both the United States and China, the considerations that guided the development of the crisis surrounding Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan (and beyond it) were not only related directly to Taiwan or the international arena. They were also, and perhaps mainly, internal considerations: The United States was heading into midterm elections, and China was preparing for the National Congress. In the United States, the China issue had long ago, certainly after the 2016 elections, become a way to score political points on both sides, with Democrats and Republicans competing over who could denounce China more loudly. In this context, Taiwan had become a tool for candidates to show their voters how strong they were in standing up to China. In other words, if Pelosi had given up on her visit or if the president had publicly (and firmly) asked her not to visit Taiwan, this would have been perceived as a sign of weakness and cost political support.

The Chinese National Congress, where Xi was standing for re-election, potentially for an unprecedented third term as the party’s general secretary, created a situation where the Chinese president also needed to look strong and responsive and could not show restraint, even if he had wanted to. Moreover, internal problems, chiefly protests against the zero-COVID policy, were also a motive for redirecting public attention toward Taiwan. While in China’s case, it is very doubtful that the president would have wanted to show restraint in any case—the sense that Taiwan was slipping away and that the United States was violating the agreements was already too strong at that point—the level of the response could have been more moderate, were it not for the internal needs.

After the congress in China and the midterm elections in the United States, it appeared briefly that the two countries were trying to somewhat soften the tone. Xi and Biden’s meeting on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Indonesia (November 2022) seemed positive, and the leaders agreed to reopen previous channels of communication, set up working groups for dialogue on contentious issues on the agenda, and work together on areas of agreement, such as the climate crisis. It was also agreed that Secretary of State Antony Blinken would visit China to implement the new dialogue and particularly to establish “guardrails” for the relationship, in order to prevent it from deteriorating into a more serious and violent conflict. His visit to Beijing was scheduled for January 2023. The leaders’ declaration that “a nuclear war should never be fought and can never be won” was also seen as important, especially against the backdrop of Russia’s statements throughout the war in Ukraine (Sacks, 2022). However, differences in phrasing and nuances between the statements from Beijing and Washington made it clear that there was still a long way to real agreement. Furthermore, even after the meeting, Chinese military activity around Taiwan continued the trend of increasing the threat.

If the new status quo can be termed increased “threat diplomacy,” then this kind of conduct by China does indeed continue today. Given that the United States and its allies continue to frequently give China good reasons to express its displeasure, occasional flashpoints in the Taiwan region also occur from time to time. Thus, in November 2022—about a week before the Xi-Biden summit, in light of British trade minister Greg Hands’ visit to Taiwan (Yu & Adu, 2022) and the opening of a trade office by Lithuania in Taiwan (MOFA ROC, 2022a), alongside economic and technological talks between the United States and Taiwan, more Chinese aircraft than usual penetrated Taiwanese airspace and also crossed the median line. Toward the end of November 2022, local elections were held in Taiwan, and the governing party suffered a stinging defeat again, even greater than the 2018 local elections, winning only 5 out of 22 cities and counties. Interpretations of this loss included the island’s problematic economic situation (voting based on the internal situation and not according to global geo-strategy) and also claims that perhaps a significant portion of Taiwanese are not very satisfied with the government’s policy on the Chinese issue (Hsiao, 2022).

At the end of December 2022, when President Biden signed the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for 2023, which for the first time included provisions allowing the sale of up to 10 billion dollars of military equipment to Taiwan (by 2027) as well as additional assistance for the near term (MOFA ROC, 2022b), record numbers of incursions into Taiwanese airspace occurred again: on December 26, 2022, 71 aircraft penetrated Taiwan’s ADIZ, of which 43 crossed the median line—the likes of which were not reported even immediately after Pelosi’s visit in August (DW, 2022). The following day, Taiwan announced that it would extend mandatory military service from four months to a year starting in 2024 and would increase training (Wang, 2022).

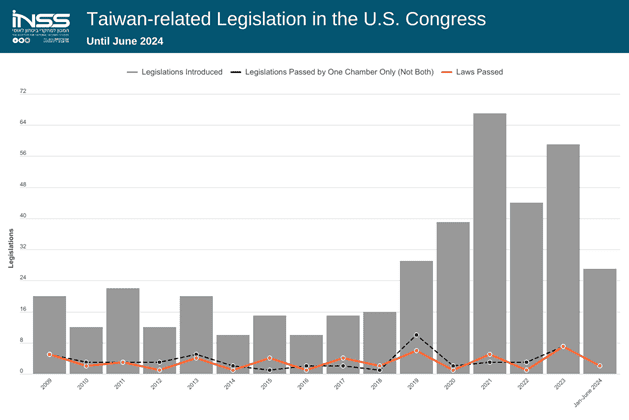

The beginning of 2023 did not mark any positive change in the tension surrounding Taiwan. China continued to conduct major exercises around the island, which decided to lengthen the duration of mandatory military service from three months to a year (starting in 2024, alongside other organizational changes in the Taiwanese defense system that began slightly earlier) (Dotson, 2023), and the United States continued to present the “Chinese threat” and to increase its efforts to raise the issue in a variety of forums, in both the West and Asia. A special committee was created in the US House of Representatives to address the various challenges that China, and specifically the CCP, poses to the United States.[7] Among them, Taiwan received special attention. The committee’s first session, at the end of February, was explicitly called “The CCP’s Threat to America.” In it, the committee proposed seven bills, including three directly addressing Taiwan (Cox, 2023). In effect, starting in 2019 and increasingly from 2020, the US Congress became more involved in interactions between the United States and China in general (while focusing attacks against the Communist party specifically, which China interprets as an attack on the system of government), especially on issues related to Taiwan, in a very hawkish manner. We can see that the number of bills related to Taiwan (positively toward Taiwan and negatively toward the PRC, not including bills related only to China) that were presented at the House of Representatives increased by 50 percent from 2018 to 2019 (from 16 to 29). From 2020 to 2023, the average annual number jumped to about 53 bills per year—almost four times the average from 2010 to 2018. While only a few of these bills were enacted as laws—passed in the Senate and signed by the president—these statistics illustrate the intensity of the anti-China and pro-Taiwan rhetoric in the United States in recent years.

Figure 6: Legislation related to Taiwan in the US Congress, 2009 to June 2024

Source: Congress.gov

After Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan as Speaker of the House of Representatives in August 2022, news of a planned visit to Taiwan (that did not ultimately occur) by the new speaker of the House of Representatives, Kevin McCarthy, in the spring of 2023 did not help alleviate the tension and again showed how increased rhetoric by Congress heightens tensions even when it does not result in concrete actions. The number of congressional delegations to Taiwan and the number of participants in them has also increased considerably in recent years, reaching five official delegations with 32 participants in 2023 (compared to one delegation with one participant in 2019—before COVID-19—and three delegations in 2021 and 2022, with 14 and 19 participants, respectively) (Stampfl, 2023). At the same time, a separate series of events surrounding the discovery of a “Chinese spy balloon” over North America in late January and February 2023 again made the dialogue between China and the United States almost nonexistent and certainly not positive.

Immediately after the news of the balloon’s discovery, the American secretary of state announced the cancellation of a planned trip to China, instantly annulling the success of the meeting between the presidents in November. The two countries launched into a mutual frenzy, and if there was some hope of dialogue that, especially in the Taiwanese context, would maintain coordination between the superpowers, this hope was shattered. In the middle of February, on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference, Secretary of State Antony Blinken met with the director of the CCP Central Committee Foreign Affairs Commission Office (the highest-ranking diplomat in China, who was foreign minister previously and became foreign minister again afterward, after the removal of Qin Gang), Wang Yi. However, the meeting did not bear diplomatic fruit and did not reignite significant dialogue between the countries, and the main reports that came out of it were mutual condemnations. Alongside the condemnations, with the anniversary of the outbreak of war in Ukraine in the background, the United States also issued warnings against supplying Chinese weapons and combat equipment to Russia, while China claimed American hypocrisy in the Taiwanese context. That is, according to China: how can the United States demand from China not to supply weapons to Russia when it is supplying weapons to Taiwan? This comparison is based on the Chinese idea that the principle of territorial integrity, as it applies to Ukraine, also applies to China’s integrity (with Taiwan inside it).

The Taiwan issue also came up several times at the important political event known as the Two Sessions in March 2023. Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang was asked about Taiwan at a press conference and began his response by quoting from the preamble to China’s constitution, which mentions Taiwan: “Taiwan is part of the sacred territory of the People’s Republic of China. It is the sacred duty of all the Chinese people, including our fellow Chinese in Taiwan, to achieve the great reunification of the motherland.” (台湾是中华人民共和国的神圣领土的一部分。完成统一祖国的大业是包括台湾同胞在内的全中国人民的神圣职责). In addition, he drew a parallel between Taiwan and Ukraine. Wang Huning, a member of the Politburo Standing Committee who was elected chairman of the national committee of the CPPCC at the event, reiterated the same principles presented in the past: the Taiwan issue must be resolved; acceptance of the One China principle and the 1992 Consensus are a condition for this; the peaceful resolution of unification is paramount; “Taiwan independence,” separatism, and foreign intervention must be firmly opposed; and China must work with its “compatriots” from Taiwan to achieve national revival. The view that the United States is using Taiwan to control China (以台制华) is also a widely cited argument, while emphasizing that the Taiwanese problem is actually the result of Western colonialist-imperialist intervention in East Asia (see, for example, Taiwan Affairs Office, 2023).

During the Two Sessions, it was reported that President Tsai intended to visit the United States in the spring—a report that provoked especially negative responses in China. Although such a visit meant US House of Representatives Speaker Kevin McCarthy would not visit Taiwan, from China’s perspective both the United States and Taiwan were being underhanded. It seemed that such a visit by the president, which had not occurred since 2019, would not necessarily lead to a weaker Chinese response; it might instead provoke escalation. At the same time, Taiwan announced that it would agree to increase the number of flights between it and the PRC—an issue that China had been trying to advance since it removed the COVID-19 restrictions a few months earlier. However, the continuing increases in China’s defense budget alongside more aggressive statements by China’s president—who was elected for a third term and also as chairman of the Central Military Commission—did not foster a sense that calmer practices and dialogue in the region were within reach.

And indeed, on March 29, 2023, Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen landed in New York for the first time since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was her seventh visit to the United States as president of Taiwan. As usual, her visit was defined only as a “stopover” on her way to Central America, not as an official visit. China strongly opposed the visit, especially the meeting between the president and Speaker of the House of Representatives Kevin McCarthy during her subsequent “stopover” on her way back to Taiwan. While the United States downplayed the meeting, China saw it as another affront and again significantly increased the rate of incursions by its aircraft, as well as large-scale drills and exercises near Taiwan (Wu, 2023b), in keeping with the “new status quo.” These exercises included dozens of aircraft incursions and median line crossings while practicing the use of Chinese aircraft carriers east of the island and the increased use of drones. The visit to Taiwan by Michael McCaul, chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, immediately after Tsai’s US visit also prompted anger in Beijing, although the responses to it were relatively restrained, and mainly consisted of personal sanctions against McCaul (Wu 2023a; 2023c).

It appears that at this stage, the two sides—the American administration and the PRC’s government—sought to find ways to soften the discourse and the actions between them and to renew crucial collaborations, notwithstanding the inter-superpower competition. Thus, starting in May 2023, a series of high-level meetings and mutual visits brought some calm and led to the renewal of dialogue between China and the United States, which was suspended surrounding Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan. The key events in this context were Blinken’s visit to China and US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s meeting with Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe in Singapore in June 2023; visits to China by Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in July; Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo’s visit to China in August; the resumption of the dialogue (U.S. Department of Treasury, 2023) of joint working groups on cyber and economic issues in September; the visit to China by a delegation of senators led by Chuck Schumer in October; and the climax—the Chinese president’s visit to San Francisco in November and the summit held between him and President Biden, after which the military dialogue between the countries was also renewed. However, in August 2023, for the first time in history, an arms deal with Taiwan was signed as part of the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) program. While it was a relatively small sum (80 million dollars), the use of the FMF—a program that is supposed to finance sovereign countries—to finance a deal with Taiwan was a fundamental deviation from the norm (Atwood, 2023).

From the Elections in Taiwan to the Inauguration of President Lai

All of the meetings described above were held while Taiwan was in the lead-up to elections for the presidency and the legislature on January 13, 2024. According to reports, China attempted to influence the elections in a variety of ways, particularly through social media and disinformation. But despite the PRC’s attempt to tip the scales in favor of the Kuomintang, William Lai Ching-te, the representative of the DPP, the governing party during the past eight years, was elected with 40 percent of the votes. The DPP lost its majority in the parliamentary elections, falling from 61 to only 51 seats. In contrast, the KMT (Kuomintang) increased from 37 to 52 seats and became the largest party. In addition, the TPP party also increased its representation, from 5 to 8 seats. This led to a situation that is uncommon in Taiwan’s electoral history, in which the president comes from one side of the political map without a parliamentary majority. The TPP could also benefit from holding the balance of power and may attempt to leverage its position without being committed to either of the major parties (Dreyer, 2024).

President-elect Lai had spoken in the past about Taiwan already being “sovereign and independent” (Reuters, 2023, 2024c)—the core issue in the dispute between Taiwan and the PRC, of course—so many commentators tend to see his election as a provocation toward China. But in practice, with a potentially antagonistic parliament, a balancing dynamic has emerged. In other words, for all of the countries involved, from China to Taiwan to the United States, an opportunity has emerged to bridge the gaps in the conflict or to moderate them, through a balancing act between the president (who China sees as divisive) and the parliament, whose majority parties seek greater cooperation with China.

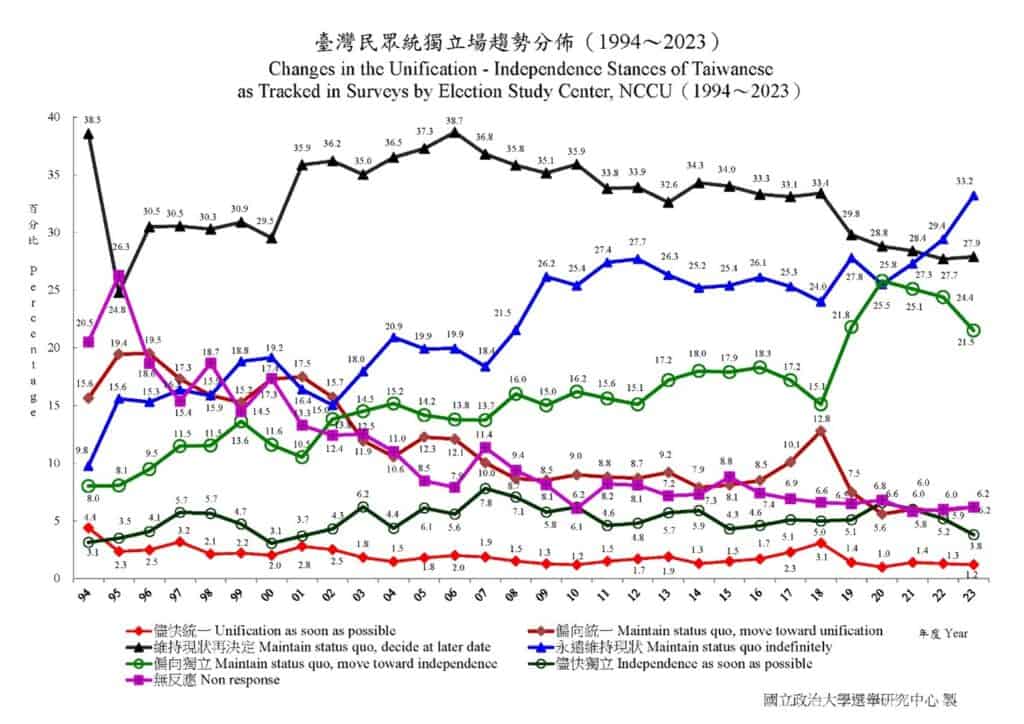

Figure 7: Changes in Taiwanese stances on the issue of unification/independence, 1994-2023

Source: Election Study Center, National Chengchi University

Despite the elections, China did not change its policy on Taiwan and continued to claim that first and foremost, Taiwan is part of it and there will be no compromises on this point; second, the primary goal is to bring about Taiwan’s return “peacefully”; and it also claimed that only if it becomes clear that there is no chance of such a unification would it not rule out the use of force. Its relatively moderate response—in which it repeated in various ways the importance of the One China principle and added that this principle is “the strong anchor for peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait”—perhaps hints at an attempt to maintain quiet in the region at this time. The US president responded explicitly to the question of Taiwanese independence immediately after the elections, saying that Washington “does not support [Taiwanese] independence,” and this, too, was an attempt to maintain the status quo (Sacks, 2024).

However, at the beginning of February 2024, China declared its intention to divert the M503 airway eastward toward Taiwan—a move that was seen not only as violating prior agreements between the two (regarding joint, prior coordination of airways near the island) but also as a military threat (Brar, 2024a). And while in response, the United States called on China to stop the military, diplomatic, and economic pressure on Taiwan, it simultaneously announced that it had completed the upgrade of 139 Taiwanese F16 aircraft at a cost of 4.5 billion dollars (Tirpak, 2024). It also held a military exercise with Japan not far from Taiwan (Lendon, 2024) while noting—in another simulation of the United States and Japan—that China is the hypothetical adversary in an invasion of the island (Brar, 2024b). A parallel visit by a congressional delegation in Taiwan led by Mike Gallagher (The Select Committee on the CCP, 2024a) did not help ease the tension, of course, nor did a financing request by the US Department of Defense for 500 million dollars’ worth of weapons for Taiwan (Chung, 2024), which was published in the middle of March, or the approval of another arms deal with Taiwan as part of a broader law for military aid and arms transfers to Israel, Ukraine, and US allies in the Indo-Pacific region (of which between 2 and 4 billion dollars are apparently intended for Taiwan) (U.S. DoD 2024; Forum on the Arms Trade, n.d.).

But despite all this, the efforts to maintain some stability between the United States and China on the Taiwan issue continued: As mentioned above, in February, Wang Yi and Blinken met on the sidelines of the Munich Conference (Murphy & McBride, 2024); and at the beginning of April, President Xi and President Biden spoke, with the Taiwanese issue on the agenda (Xinhua, 2024). The American side mainly emphasized stability and peaceful methods, while the Chinese side emphasized Taiwan as a part of China and demanded that the United States fulfill its declarations on the One China policy (principle—in the Chinese version) in actions. Another visit by the US Treasury Secretary to China at that time aimed to continue to stabilize relations. On the other hand, at that time, it was reported that the US deputy secretary of state claimed that AUKUS submarines could be used against China in the case of a military conflict surrounding Taiwan, or to deter Chinese aggression (LaMattina, 2024). In parallel, former Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou from the Kuomintang visited China again (as he had a year before), and even met with the president of China (Hioe, 2024a; Tsai, 2024). This visit, which included declarations seeking to highlight the connection between the PRC and Taiwan, was seen as an attempt to undermine the policy of the ruling party in Taiwan and also, implicitly, American policy.

At the beginning of President Lai’s inauguration speech on May 20 (Office of the President, ROC, 2024a), the incoming president mentioned the inauguration of the first elected president of Taiwan in 1996. He stated that the then-president (Lee Teng-hui of the Kuomintang) conveyed to the international community at his inauguration the message that Taiwan is “a sovereign and independent country” (主權獨立的國家). But while President Lee stated at his inauguration that Taiwan is sovereign, he explicitly said that “the disputes on both sides of the strait do not relate to questions of ethnic or cultural identity, but only to an argument over the system and way of life. Here we have no need and we cannot adopt the path called ‘Taiwan independence’” (海峽兩岸沒有民族與文化認同問題, 有的只是制度與生活方式之爭。在這裡,我們根本沒有必要,也不可能採 行所謂「台獨」的路線) (Office of the President, ROC, 1985).

Lai’s short comment did not become the topic of the speech, and later Lai attempted to display reconciliation toward the PRC, but his opening remarks, and his repetition of the position expressed by his predecessor in 2021 regarding the “four commitments” (四個堅持)—maintaining a free, democratic, constitutional system; preserving Taiwan’s independence from China’s influence; preserving Taiwan’s sovereignty from foreign forces; and deciding Taiwan’s future based on the will of its citizens—were enough for the PRC to declare that the new president is a separatist and divisive, and that he must bear the consequences (ChinaPower, 2024a).

Thus, President Lai’s inauguration in May was accompanied by a massive Chinese military exercise (Joint Sword 2024A, hinting that there would be additional similar exercises) which was defined as a “punishment” for Lai’s inauguration speech, but unlike the military maneuvers around the island following Pelosi’s visit in August 2022, this exercise only lasted two days, did not involve launching missiles around the island, and included fewer air and sea platforms. However, the May 2024 exercise included military activity in areas where the China Coast Guard did not operate in August 2022, in closer proximity to the island, and involved a record number of air and sea platforms around the island on a single day compared to previous exercises (ChinaPower, 2024a, 2024b; DW, 2024; Peterson et al., 2024).

China also announced steps against American companies involved, according to the announcements issued in China, in the sale of weapons to Taiwan and against former member of Congress Mike Gallagher for his support for Taiwan (Reuters, 2024a, 2024b, 2024c). China also suspended its talks with the United States on nuclear proliferation in protest of the arms sales agreements and American aid to Taiwan (Roth, 2024). Furthermore, in the days and weeks after the inauguration, China announced that it intends to severely punish, including the death penalty, those who “insist on ‘Taiwan independence’ and dividing the country” (“台独”顽固分子分裂国家) and published an initial list of names of candidates for prosecution (Ministry of Justice, PRC, 2024).

In parallel to the president’s inauguration, Taiwan’s legislature, in a clear antagonistic move led by the Kuomintang and the People’s Party, pursued a legal reform (or revolution, depending on one’s perspective) to provide the legislative branch with closer supervision of the executive branch and the president. However, although in the context of these legislative changes, press reports mainly emphasized the dimension in which the changes are supposed to help the “pro-Chinese” position in Taiwan, the implications of the reforms go well beyond this issue. First and foremost, they relate to internal Taiwanese policy issues, restricting the governance capabilities of the executive branch and the president, as well as questions related to the defense budget and to reports connected to the defense industry and arms imports in general (Hioe, 2024b).

In any case, there is great opposition to these changes, and the legislative process is currently accompanied by intense public protests, so it is too early to know where things are going. What is clear is that in the current term, the legislative branch, which is antagonistic to the executive branch and the president, intends to provide a practical and conceptual alternative to the DPP, which could—from the perspective of the PRC—be an encouraging factor in the direction of a non-military takeover of Taiwan in the future. Furthermore, from this perspective, the internal tensions in Taiwan are a positive thing, as they create an opening for greater Chinese influence in the media and social networks, and they undermine the power base of the executive branch, certainly for moves seen as unilateral by Taiwan on the Chinese issue.

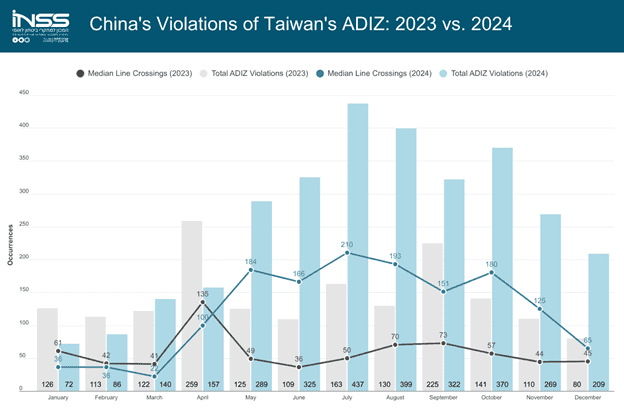

Conclusion

During the past eight years, China’s actions can be interpreted as a policy sometimes called “threat diplomacy” in the literature. This is not a policy that began with Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan. It includes a combination of political, economic, diplomatic, cybernetic, and military leverage, and is pursued alongside an “enticement policy” that attempts to present Taiwan with the possible benefits of unification as an overall strategy. However, the threat dimension has dominated the strategy since 2016, and in almost every year since then it has been augmented and intensified. Over these eight years, the systematic use of military threats, especially aircraft incursions, has greatly intensified twice: first, at the end of 2020, and second, since Pelosi’s visit. This is in terms of the number of incursions into Taiwan’s ADIZ, the variety of aircraft types, and median line crossings.

In this sense, the missile launches immediately after Pelosi’s visit were an exceptional case, and the fact that the Chinese military activity surrounding President Lai’s inauguration did not include such launches is important. Compared to the 1995-1996 crisis, when more missiles and more kinds of missiles were launched, for a longer period of time, it seems that the use of missiles surrounding Pelosi’s visit was more limited, even if it prompted great global interest at that time. The fact that China apparently chose to use DF-15B missiles and not its more advanced missiles relevant to A2/AD against the United States (for example DF-21D missiles) could also demonstrate a certain restraint. However, there is no doubt that today’s China is very far from and much more advanced than the China of the 1995-1996 crisis. It is doubtful that two American carrier battle groups would deter China today as it did during the crisis. China itself now has two operational aircraft carriers (the Liaoning and Shandong), which maneuvered during the 2022 crisis and also in May 2024, and another aircraft carrier, the Fujian, is undergoing sea trials. It has also bolstered its nuclear arsenal and made extensive changes to military organization.

On the other hand, it is important to note that China is very consistent in its conduct toward Taiwan. Its declarations have been completely consistent over the past three decades (and more), and the strengthening of ties between China and Taiwan has continued despite President Tsai taking office in 2016 and the increasing use of “threat diplomacy.” In effect, even China’s military actions in the region come after specific Chinese statements that it will act in this way. It appears that currently, against the background of economic problems and issues of military weakness (from the defense minister who disappeared to the replacement of a large number of generals and reports of weapons deficiencies), China needs stability in the strait, not escalation.

In contrast, the American rhetoric that American policy on the Taiwan issue has been consistent since the 1970s does not, from China’s perspective, cohere with the United States’ actions on the ground, especially in recent years: from major weapons deals to visits by senior officials to economic agreements, and of course declarations (intentional or slips of the tongue— – from China’s perspective it does not matter).

Taiwan itself sometimes seems like a bystander in its own story, becoming a pawn in a much larger game between the two superpowers. Thus, Taiwan is not just a strategic point in the region, but a vital symbol: For China—a symbol of the success or failure of its “national revival”; for the United States—a symbol of its struggle against dictatorship and tyranny and in favor of the values of freedom and democracy (and also, perhaps primarily, a symbol of American global dominance). It is also clear that there is enormous importance in Taiwan’s concrete strategic equity, as made clear at the beginning, especially against the backdrop of American efforts to create a system of alliances in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond, but this sometimes seems secondary to its symbolic importance. However, Taiwan is not just a bystander: Insofar as it projects symbols that explicitly or implicitly choose a side in the story, the superpowers harden their positions, and such positions sometimes solidify Taiwan’s policy in the next phase. Taiwan’s attempts to increase its strategic equity, for example on the chip issue, alongside successes in recent decades could also lead its allies to work to decrease their dependence on it (which is already happening), and thus the idea of the Silicon Shield might collapse in the medium term. This is also true of China’s responses to its very specific dependence on Taiwan in this respect, while ultimately it is Taiwan that has developed great dependence on China. Moreover, while the changing Taiwanese sense of identity emphasizes Taiwan’s distinctiveness from the PRC, the vast majority of Taiwanese still prefer maintaining the status quo and not breaking it (whether toward independence or unification). It is also evident that one of the main reasons Taiwanese oppose unification is related to the PRC’s political system and the importance that they ascribe to the liberal democracy in which they live (Chong et al., 2023).

Thus, while the increasing tension surrounding the Taiwan Strait is sometimes described as deriving only from the actions of the PRC, I would like to argue that the escalation of the tension also stems from the conduct of Taiwan and the United States. The ideal status quo, which they are both apparently striving to maintain (Dickey & Kent, 2024), has not been static, certainly not in the past decade. The new status quo—the term for the Chinese measures of threat diplomacy presented above—is not only the result of PRC aggression. It can, of course, be argued that the American policy on the Taiwan issue was and remains mainly responsive—the United States responded to escalatory measures by China (like the “equation system” familiar in the Middle East)—with China then escalating further, and so on, leading to a mutually reinforcing cycle of deterioration. However, the question of who started the cycle is also not as easy as it seems: not only does the response depend on when you start to examine the issue, it is a dangerous dialectic of a trilateral relationship (at least; more countries can be added to the discussion, of course) in which there is no single starting point and no single side that changes the picture on its own. On the other hand, the fact that from time to time China uses the Taiwan issue as a whip vis-à-vis the United States due to the sale of American weapons for example, and suspends talks that are not related to Taiwan, emphasizes how this issue goes far beyond the strait itself.

The PRC still maintains relations with the Taiwanese opposition party, the Kuomintang. After its impressive success in the local elections in November 2022, along with the worsening economic situation in Taiwan, and its relative success in the legislative elections in January 2024, China has come to see the Kuomintang as a viable partner in the pursuit of the ultimate goal of unification. While in recent years a number of research institutes have considered various war scenarios in which the PRC attacks Taiwan, it seems that a scenario in which China attempts to bring about change in Taiwanese public opinion—through internal pressure, influence campaigns, economic enticements, as well as a potential blockades and threats—while attempting to cooperate with the Kuomintang, and thus bring about a situation in which the Taiwanese people reaches the conclusion that unification is inevitable, could be more likely. However, it is not clear whether a continuation or intensification of “threat diplomacy” and the various influence campaigns will help or hinder the Kuomintang’s future success—as seen in the 1995-1996 crisis, in the sunflower protests of 2014, or in the responses to the events in Hong Kong around 2019, Chinese actions seen as harsh and proactive often produced the opposite outcome.

In reality, the PRC currently has no interest in using force to change the status quo—in the sense of the continuation of the political situation on both sides of the strait. A military campaign of “unification” would not only be very expensive, in both resources and in human lives, it could also bring disaster to Taiwan itself and thus, even if it ultimately succeeds, in the cost-benefit equation the cost could be unfavorable. Such a military campaign, as China has seen in Ukraine, could also turn the Western world against it economically (sanctions) and even prompt military involvement by the United States, and perhaps also by its allies in the region (Japan, South Korea, and Australia, for example). Such costs could also hurt the Chinese government’s domestic legitimacy, and of course lead to further damage to China’s economy and industry: China relies on the supply of chips for almost every industry in the country, and for now (China is working to change this), this supply is dependent Taiwan. War would mean interrupting the supply chain from Taiwan and creating enormous problems for China and in turn the entire world, which relies on the production and export of its Chinese. Therefore, to the extent that the Chinese government is guided by rational considerations, a military campaign does not seem likely in the near term. However, as we know, countries are not always guided by rational considerations, and this is especially true of rulers in authoritarian regimes. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that the “status quo”—new as it may be—is not static: the average monthly number of Chinese Air Force incursions into the Taiwanese air identification zone increased from 141 in 2023 to 300 between March and November 2024 (January and February 2024 are outliers in China “turning down the heat”); the average number of monthly median line crossings increased from 58 in 2023 to 148 between March and November 2024.

Figure 8: Air incursions into Taiwan’s ADIZ by the Chinese military—monthly comparison between 2023 and 2024

Source: Brown & Lewis, n.d.

Furthermore, the increasing pace and intensity of American measures against China, whether in the Taiwanese context or in other contexts, especially in the Indo-Pacific region in recent years, are in a dialectic relationship with China’s responses, which accordingly are only intensifying. The lack of proper strategic and tactical dialogue between China and the United States could also lead to a situation in which a local incident (for example a plane crash, as in 2001; or a confrontation between two ships in the crowded area of the South or East China Sea, certainly against the backdrop of the conflict between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea) could unintentionally ignite an escalating series of military responses, at a time when public opinion within both superpowers is not sufficiently tolerant to accommodate such events. Throughout the period of the 1995-1996 crisis, the two powers were in direct contact, meetings were held frequently, and at times a return to the status quo as it was understood in the 1992 Consensus for example, seemed possible. In contrast, in the ongoing crisis since Pelosi’s visit, it appears that the mechanisms of dialogue and damage control between the two superpowers have become an offensive tool (canceling or maintaining them as a political response), and here perhaps lies the main real danger, first of all in the near term. China sees mutual visits by senior American and Taiwanese officials as an unequivocal provocation, and they test the superpowers’ ability to maintain any constructive dialogue and prevent escalation. The fact that 2024 was also an election year in the United States, which, even without the Taiwan issue, raised the level of tough declarations on China, also raised concerns about the exacerbation of the tensions.