Strategic Assessment

The civil war in Syria, which has been ongoing for more than a decade, is considered the greatest humanitarian catastrophe of the twenty-first century. President Bashar al-Assad remains in power, but Syria is far from a functioning or stable country. Out of a population of about 22 million people, the war has taken the lives of more than half a million residents and left about 15 million in need of humanitarian aid. The war has also led to the worst refugee crisis since World War II. More than six million Syrian refugees who were forced to leave their homes moved to live in neighboring countries—mainly Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, and European countries. About 90% of them do not receive basic living necessities in the host countries and are seen as an economic and political burden. So far about 750,000 refugees have returned to Syria since 2016, but despite the regime’s declared policy that they should be repatriated, the return of millions of refugees to Syria is far from the reality. The reasons for this are related to the refugees’ fear of the regime taking revenge on them or of forced conscription, and to the perception that there is no future for them given the dismal situation in Syria, which has been devastated by the war. With the end of the battles, refugee flight is being replaced by emigration, and many Syrians are interested in leaving the country for a better future. This article discusses the Syrian refugee issue from the perspective of a war that has continued for more than a decade and the implications of the refugees for the host countries, including for their geopolitical environment. The study examines the refugees’ degree of integration in the host countries and also discusses the question of their return to Syria and its potential rehabilitation.

Keywords: Refugees, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, Iraq, Turkey, Europe, rehabilitation

Introduction

The civil war in Syria that broke out in March 2011 is considered the greatest humanitarian catastrophe of the twenty-first century and has caused masses of Syrians to flee their country since it began. The war has taken the lives of over half a million residents (SOHR 2023). President Bashar al-Assad remains in power, but Syria is far from a functioning or stable country.

Despite the lull in the fighting compared to previous years, the humanitarian situation in Syria is worsening: more than 90% of residents live below the poverty line, including those in areas under Assad’s control. Out of a population of about 18 million people, 15.3 million are in need of humanitarian aid; the Syrian pound continues to fall, and at the beginning of 2024 it dropped to a new low of over 14,000 pounds to the dollar (Khan 2023); despite the average monthly salary increasing to 12.5 dollars, this is still insufficient to cover the basic needs of the population in the face of increasing inflation, when the estimated cost of a basket of basic goods is 90 dollars (World Food Programme 2023); in the past three years 70% of households in Syria experienced a decline in living conditions and in their ability to obtain basic goods; in 2023 fuel prices increased more than 150% due to a decision by the regime, which led to the renewal of protests by residents, especially in southern Syria. The electricity supply is irregular throughout the country, and some report days without any electricity (Dadouch 2023; William 2023). Given these trends, the COVID-19 and cholera epidemics that broke out in recent years worsened the humanitarian crisis; about half of the medical institutions in Syria are non- or only partly functional. Meanwhile, disastrous climate trends are being felt in Syria—the worsening of the water crisis given the ongoing drought, the spread of a cholera epidemic, and the earthquake that occurred in February 2023 and led to tens of thousands of deaths and large-scale destruction (OCHA 2021, 2022b; United Nations Security Council 2023).

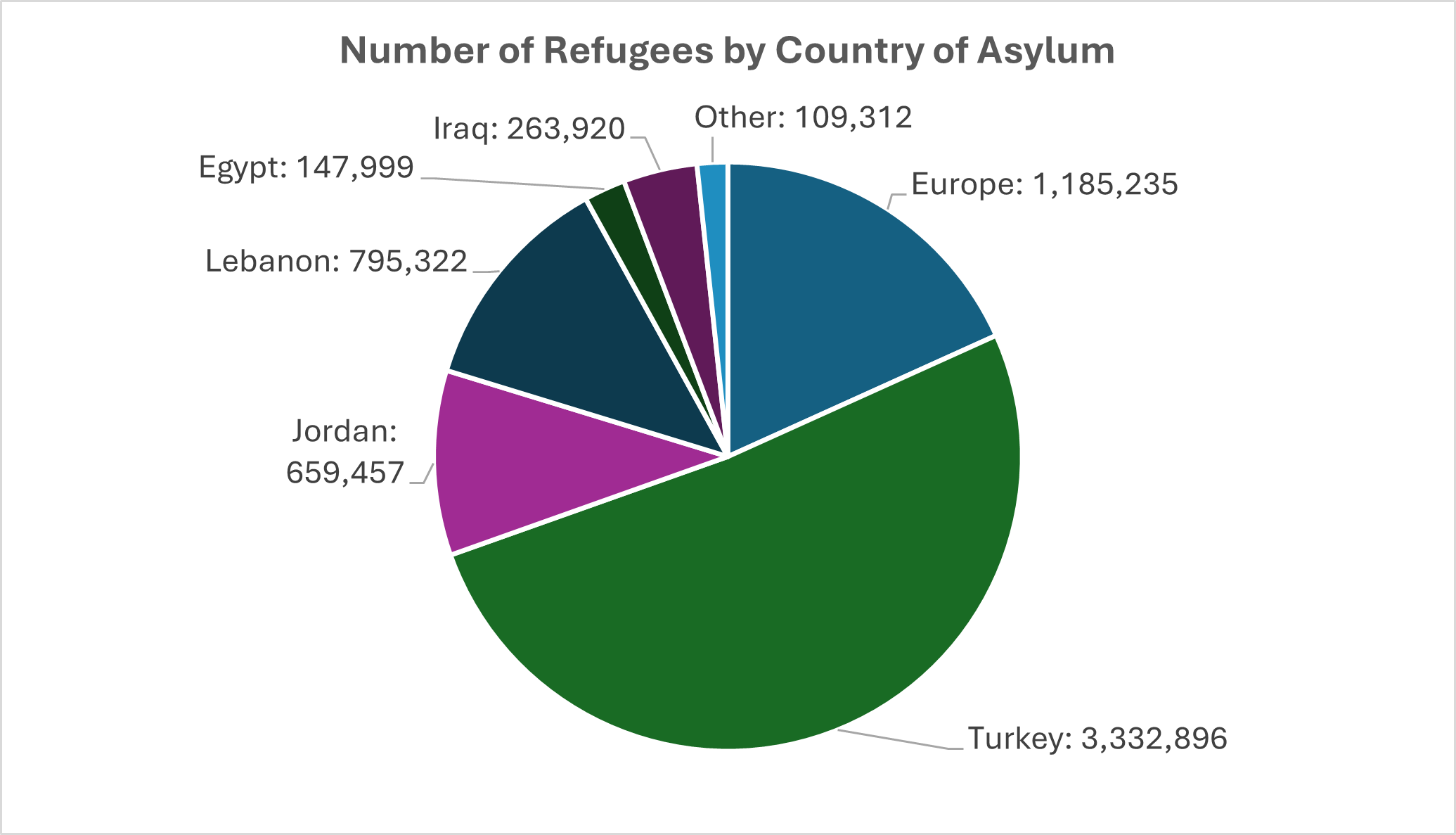

The ongoing bloody conflict in Syria, with an estimated population of 24 million residents as of 2024 (compared to 22 million in 2011), has displaced about 6.8 million residents (Syrian citizens who fled their homes because of the war but remained inside Syria) and created another 5.5 million refugees[1] who fled Syria and are not included in population estimates. The refugees have found asylum in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, and other countries in Europe and North Africa (UNHCR n.d.-g, n.d.-h).

Figure 1 | Source: UNHCR Data for 2023

Background

This article discusses the Syrian refugee issue from the perspective of a war that has continued for more than a decade and the implications of the refugees’ presence for the host countries, including for the geopolitical environment in the Middle East and in the international arena. The study examines the refugees’ degree of integration in the host countries while focusing on their humanitarian and social situation, and the attitudes of local communities and authorities towards them, and finally discusses the question of their repatriation to Syria and its potential rehabilitation.

According to international law on refugees, enshrined in the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which came into effect in April 1954, refugees have several rights, chiefly including a prohibition against deportation or repatriation. This means that signatory countries are prohibited from repatriating refugees to the territory of the country where their lives or freedom are endangered. In addition, the convention protects asylum seekers even in cases where the refugees have entered a country illegally and without the approval of the host country. According to the convention, in this case too, the country is prohibited from deporting the refugees, on the condition that they came directly from the territory of the country where they are in danger. The convention also discusses the assimilation of the refugee population within the country of asylum. In particular, it states that the host country must allow the refugees to work as well as protect their rights to education and welfare, and ensure social security rights that are equal to those granted to citizens of that country. However, the convention does allow the receiving country to deport the refugees due to considerations of “national security and public order” (UNHCR 2010). And the many limitations in the convention—including countries’ ability to “choose” to relate to refugees as immigrants and thus not to apply the rights of refugees that they deserve by virtue of the convention, combined with the lack of an effective UN enforcement mechanism—allow countries to violate refugees’ rights (Kirişci 2021).

Most of the aid to the refugees in the countries studied comes from humanitarian organizations and UN agencies. Each year, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provides aid including medication, food, drinking water, fuel and heaters, tents, thermal blankets, and winter clothing to refugees in Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, and Egypt. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the agency provided aid to local hospitals and established temporary medical clinics in refugee camps. The aid was provided as part of the Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP) (UNHCR n.d.-f), which was founded by the UNHCR and the UN Development Programme (UNDP) as part of a concerted effort surrounding the Syrian crisis. In 2022 the budget required to execute this plan was about 6.1 billion dollars. The budget required for the activity of the Humanitarian Response Plan for Syria was 4.4 billion dollars that year. Thus the total sum needed to aid the residents of Syria is about 10.5 billion dollars per year—an amount that reflects the severity of humanitarian needs in Syria and the region following more than a decade of this crisis (OCHA 2022a). However, it seems that despite the growing humanitarian needs, funding under the auspices of the UN is actually decreasing from year to year and is insufficient to meet all the needs (Hickson & Wilder 2023).

Between Refugees and the Security and Economic Situation in the Host Country

Theoretical literature on the links between the presence of refugees and the security and economic situation in the host country reveals that in both developed and developing countries, the host communities (citizens and authorities) tend to perceive refugees as a threat to their security and draw a link between refugees and violence and crime. They are also perceived as a threat to social unity and employment in the country. As studies indicate, waves of refugees can indeed undermine security and be a source of regional conflicts, armed resistance, terrorist activity, and foreign intervention in neighboring countries. In addition, the economic and social consequences of the long-term presence of refugees can accelerate and increase internal tensions in the host countries, especially in developing countries where there are already ethnic tensions. This is also true in countries with precarious economic or social foundations and in countries surrounded by hostile neighbors. Similarly, studies show that politicians receive greater popularity when they express xenophobia and blame refugees for a lack of housing and employment, for undermining national and cultural homogeneity, and for emphasizing ethnic tensions (Loescher 2002).

The arrival of refugees in host countries involves economic consequences, chiefly competition between the refugee and local communities over resources such as food, water, housing, and medical services. The presence of refugees in the host countries increases demand for education and for public, social, medical, and sanitary services, which can increase the burden on the host country (Barman 2020). However, studies indicate that the immigrants or refugees that are added to the labor market of a country have little to no impact on the wages and employment of local citizens. Furthermore, immigrants and refugees can bring skills, knowledge, and innovation to the host communities that can drive economic growth, though these are often not well-utilized. In cases in which the host countries, the private sector, or the international community work to create opportunities to integrate refugees into the labor market, they have made a positive impact on the economy of the host community (Bahar and Dooley 2020; Taylor et al. 2016).

In countries in which the economy is in decline or there is political instability, the presence of many refugees can contribute to the general sense of crisis, attitudes towards the refugees may deteriorate, and they are sometimes even blamed for the situation as a kind of scapegoat (Ragnhild and Karadawi 1991). This description fits with our findings from analyzing the local destination countries for the Syrian refugees—Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon.

While in 2024 Syria is still not considered a safe country for the refugees to return to—due to their persecution by the Syrian regime and the continued existence of combat zones in certain areas—, in countries such as Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon, significant efforts are being made to deport and repatriate the Syrian refugees. This trend was accelerated following the process of regional normalization with the Assad regime, which began at the end of 2021. The most prominent of them is the Jordanian initiative, which, among other things, makes the normalization of relations with the regime conditional upon the provision of general amnesty, which would allow the refugees a safe return to Syria (Ersan 2023). During these years, the economic crisis in these countries has deepened, which has directed public frustration towards the refugees, which are a social and economic burden on the host countries.

Syrian Refugees in Turkey

Turkey is the country that grants asylum to the largest number of refugees in the world—about four million refugees, 3.6 million of whom are Syrian.

Over the years, most of the refugees have lived in urban and semi-urban areas of Turkey. During the years 2012-2013 the Syrian refugees mainly settled in camps, but as of May 2014 the camps could no longer contain the massive stream of refugees, so many dispersed throughout Turkey in accordance with their preferences and abilities. At first, they preferred to live close to the border with Syria, but they later moved to other cities where they could find work or from which they could relatively easily move to European countries (Boluk and Erdem 2016). In 2016 more than 270,000 Syrian refugees lived in 26 camps in ten provinces close to the border with Syria (compared to 100,000 in 2020). The camps were run mainly with the aid of UN agencies. Turkey’s Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency is the main body ensuring the relatively proper functioning of the camps (Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency 2017).

Since 2015, Syrian refugees have been seen as a burden on the Turkish economy and society and as responsible for the rise in food and housing prices. The entry of cheap manpower into the labor market has raised the unemployment rate throughout Turkey, especially in the country’s south. The main claim against the refugees is that they are taking over jobs formerly held by Turkish citizens, especially low level jobs that do not require education, special skills or knowledge of the language.

Turkey’s Policy Towards the Refugees

Since President Recep Erdogan came to power, Turkey has had an Islamist administration that promotes a political and religious agenda that is identified with the Sunni branch of the Muslim Brotherhood. Turkish policy towards Syria in general and the Sunni refugees in particular has undergone several upheavals and changes. At the beginning of the civil war in Syria, Turkey became an ardent supporter of the Syrian opposition and a critic of the regime. Turkey was the political and military base of the Syrian opposition and directly provided weapons and military aid to the armed opposition. When the war became more intense and Sunni civilians started to flee, many of them crossed the border to Turkey, which over time became home to about 3.5 million Syrian refugees.

Throughout the war in Syria, Erdogan has stated that Turkey sees the Syrians as part of the Muslim Brotherhood, and in the first few years he encouraged their migration to Turkey. In his view, this was a religious obligation originating in Ottoman history and heritage, to provide a “brother” with comfort and a sense of home during his stay (Cumhuriyet 2016; Karaçizmeli 2015). In April 2011, Syrian refugees in Turkey received the official status of “guests,” and about half a year later, they received the status of “entitled to temporary asylum.” In April 2013, the Turkish parliament adopted the Law on Foreigners and International Protection, which was a milestone in Turkish immigration policy. Its expansion in October 2014 granted the refugees “temporary protection,” enabling them to remain within Turkey’s borders until deciding to return to Syria, and providing them with access to basic services and rights including access to emergency treatment, shelter, food, water, medical care, education, housing, the labor market, and security (Petillo 2022). However, contrary to the conventional refugee status in Turkey, the “temporary protection” law restricts the Syrian refugees’ ability to settle in a third country. By providing this status, in practice Turkey is circumventing the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Güney 2022), despite being a party to it (UNHCR n.d.-d).

However, over the years and in light of developments in Syria, Turkey has softened its policy towards the Syrian regime and became less tolerant towards the Syrian refugees. During the years 2015-2016, it became clear that the success of the Kurdish minority in establishing independent autonomy within Syria constituted a real threat to Turkish sovereignty, as it could spark a national uprising among the Kurds in Turkey. Turkey, which was disappointed in American support for the Kurdish organization, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), decided to increase its cooperation with Russia and Iran. During those years it became clear that Assad, who had succeeded in achieving an advantage over the rebels and had retaken captured areas, did not intend to give up the presidency. Turkish understanding that Syria was not going to follow in Turkey’s Islamist direction, combined with internal pressure applied by the Turkish opposition and especially by the public over the burden that the millions of Syrian refugees had become, led to increasing difficulties in the refugees’ integration in the country and to more hostile public opinion (Rabinovich and Valensi 2020).

According to the Turkish Employment Agency’s figures, only about 140,000 Syrian refugees received legal work visas—a very small number compared to the number of working-age refugees. This figure does not include the approximately 200,000 refugees who received Turkish citizenship and do not need a work permit. All the rest, including teens and even children, work in odd jobs without permits and without social benefits and rights. It is estimated that a million Syrians are working unofficially in Turkey, usually for low pay in jobs that tend to be very exploitative and physical (DRC 2021). Moreover, studies show that Turks are uncomfortable around people from Syria, who they see as criminals and as a threat to their personal security (Akyuz et al. 2021).

Following the Turkish regime’s actions against the Syrian refugees and their increased migration to the European Union, the EU-Turkey Joint Action Plan was signed in November 2015, with the intention of increasing cooperation to support the Syrian refugees under temporary protection in the host communities in Turkey and preventing irregular flows of migration to the European Union. The plan was updated in March 2016 and included clauses such as: every refugee who crosses from Turkey to Greece in an irregular manner will be returned to Turkey; for each Syrian refugee that is returned, a different Syrian refugee will be settled in Europe; Turkey will help as much as necessary in preventing illegal migration by sea or land from Turkey to European Union countries. In order to implement the plan, Turkey received six billion euros of funding from the European Union in two installments (European Commission 2016).

Since 2020, the combination of a large number of Syrian refugees living in the cities (about 98% as of 2021) (Güney 2022) and the prolonged nature of the crisis in Syria, as well as a challenging economic crisis in Turkey that intensified due to the COVID-19 pandemic, increased the internal pressure on the Turkish government to toughen its policy towards the Syrian refugees. In addition, the involvement of some of the refugees in incidents of robbery and theft increased the locals’ opposition to their presence (Akyuz et al. 2021). All of these together led to a change in Turkish policy from accepting to opposing the assimilation of the Syrian refugees into the population. Thus, the Turkish government started to take steps to differentiate the Syrian refugees from the country’s population, segregating the refugees and settling them in refugee camps and temporary housing. In recent years, a change in public discourse towards Syrian refugees can be clearly identified—from empathy to rejection (Mencütek 2021).

Ülkü Güney’s 2021 study analyzed the attitudes of Turks towards the Syrian refugees in their country. It reveals that the Turks sees the Syrians as “disloyal” for leaving Syria and believe that they are not entitled to Turkish citizenship. Many Turks see the Turkish refugees as “guests” only. They support a policy of concentrating them in defined areas in order to reduce their integration and assimilation into Turkish society. Meanwhile, they believe that only their basic needs should be addressed, while settling them in isolated temporary camps outside of residential areas. Especially prominent is the Turkish concern that the welfare of the Syrians in their country will be at their expense, against the backdrop of economic hardship, which is expressed in considerable and determined opposition to providing financial aid to the Syrian refugees (Güney 2022). Another survey from 2021 found that 82% of Turks wanted the Syrians to be deported, compared to 49% in 2017, and Syrian refugees in the country are now reporting widespread and increasing discrimination (Hickson and Wilder 2023).

The negative attitudes have also been accompanied by a rise in racist attacks against Syrians in Turkey. In August 2021, groups of Turkish residents attacked work sites and homes of Syrians in a neighborhood in Ankara, a day after a young Syrian stabbed a Turk in a fight (Human Rights Watch 2022). In August 2022, activists from the Turkish Victory Party, which is known for its hostility towards the Syrian refugees, put up placards in the streets and neighborhoods of Istanbul province that included racist statements against the refugees. It was also reported that the party’s leader toured the streets of various Turkish cities and threatened to send the Syrians away. The rise in racist incidents in the past year, as well as the toughening of Turkish policy, increased concerns among the refugees, and according to reports, a significant portion of them are considering returning to Syria or emigrating to Europe (Al-Najar 2022).

These attitudes greatly influenced the government’s policy and led it to restrict the registration arrangements for refugees who continued to arrive from Syria. In some provinces, registration was cancelled entirely and the refugees who arrived were left without status or rights. Moreover, Turkey started to restrict the number of Syrians permitted to live in specific neighborhoods, which forced many to leave provinces with better employment opportunities (Tokyay 2022). These measures aimed to encourage refugees to return to Syria, and in many cases the authorities even forced refugees to leave the country. It is not known how many of them left Turkey and returned to their home country. According to government figures it may be over half a million people, but research institutes and press reports provide much lower estimates. The gaps in figures are well-utilized in the political struggle between Erdogan—who is trying to prove that the refugee problem is shrinking—and his rivals, who claim that the president is not succeeding in curbing the refugee’s takeover of the labor market, and thus increasing the unemployment of Turkish citizens (Ridgwell 2022).

Despite the criticism of the economic burden that the refugees supposedly constitute for the host country, it is worth mentioning their contribution to the Turkish economy. Their investments in the Turkish economy, which are estimated at over ten billion dollars during the ten years that they have been flowing into the country, and the thousands of small and medium-sized businesses that they have established, and in which thousands more Syrian refugees are employed—all of these are downplayed in this political conflict, as are analyses that indicate the damage that will be caused to Turkey’s economy if all of the Syrian refugees leave the country (Bar’el 2023).

In 2022 the European Union decided to transfer another three billion euros to Turkey to supply humanitarian aid to refugees until the end of 2024, with an emphasis on health and education, in order to help the refugees’ assimilation in Turkey (supposedly temporarily) (European Commission 2021a, 2021b). In practice, it seems that the effectiveness of the European plan is limited. While it contributed to a significant reduction in the number of refugees risking the dangerous journey from Turkey to Greece and improved their situation in Turkey, those who reached the European Union are suffering from the status of “inadmissible,” without rights or legal status, while the number of refugees sent back to Turkey as part of the agreement is negligible (International Rescue Committee 2022).

In 2022, Erdogan announced his intention to embark on another military operation in Syria, in order to establish a security strip that aims both to keep the Syrian Kurds away from the border with Turkey and to serve as a region in northern Syria to resettle around a million refugees currently in Turkey (Stewart 2022). Since the end of 2022 there have been increasing reports of the deportation in practice of hundreds of Syrian refugees from Turkey, contrary to international law, even though the military operation was not carried out (Wilgenburg 2023).

The issue of the Syrian refugees in Turkey is a case study in the volatility of the problem, the international community’s weakness in coping with it, and its potential for regional fallout as well as significant progress in Syrian-Turkish cooperation to repatriate the refugees. As a result, in May 2023 Turkey unveiled a “road map” for repatriating the Syrian refugees, which was formulated in cooperation with the Syrian regime, Russia, and Iran. According to the plan, the refugees would be “voluntarily and safely” repatriated to their country of origin, with housing in northern Syria (Middle East Monitor 2023). As of the time of writing, Syrian refugees are periodically being deported from Turkey, and according to unofficial reports, tens of thousands have been deported so far, without any progress in the plan to repatriate refugees that the leaders of the countries announced (The New Arab Staff 2023; SOHR 2024a; Wilgenburg 2023).

Syrian Refugees in Lebanon

Lebanon is the country with the largest number of refugees with respect to the size of its population. There are about 1.5 million Syrian refugees there, about half of them registered and documented by the UN refugee agency (UNHCR 2023a). They are concentrated in the Beqaa region (39%), northern Lebanon (28%), Beirut (22%), and southern Lebanon (11%) (UNHCR n.d.-g.). The wave of Syrian refugees, most of them Sunnis, led to an increase in the demographic weight of Sunnis in Lebanon. Thus, Sunnis (unofficially) became the third largest religious group in Lebanon. Over the years, drastic changes in Lebanese demography have exacerbated the already prominent ethnic tension between Muslims and Christians and between Shiites and Sunnis, and the political and economic crisis in Lebanon (Thibos, 2014).

The limited number of refugee camps stems from the Lebanese state’s bitter experience with Palestinian refugees, who have remained with the status of citizenship-less residents of the country and constitute a burden on Lebanon. About 80% of them live in rented apartments, abandoned homes, tents, and temporary structures. According to the latest UN estimates, about 60% of the refugees in Lebanon live in shelters that are not safe and expose them to danger (Hansford 2015; UNHCR n.d.-e). The dire humanitarian situation of the refugees in Lebanon has led to independent emigration, mainly via unsafe ships. In 2022, the UNHCR indicated a rise in emigration by ship from Lebanon and estimated that about 4,600 people, refugees and Lebanese, had done so for lack of any other option. As a result, several lethal incidents occurred that year. The most prominent of them was the sinking of the migrant ship from Lebanon in September 2022, which led to the deaths of about 100 people, most of them Syrian and Palestinian refugees (Antonios 2023).

Despite efforts by the European Union, chiefly funding the plan for the Advancement of Growth and Employment Opportunities in Lebanon, which was established in 2016 and was supposed to have advanced measures to improve the employment situation of the Syrian refugees, the employment rate among the refugees remained high and increased over the years (Baroud and Zeidan 2021). In 2023, 45% of the refugees of working age were employed primarily in agriculture and construction, but the low wages do not enable a basic standard of living. The dire economic situation of the refugees has a considerable impact on women, whose labor market participation rate is only 19%. Women refugees in Lebanon are largely dependent on men and on their relatives when it comes to their livelihood (Government of Lebanon and United Nations 2023). The limited employment options for the refugees have led to a situation where 90% of them are living in extreme poverty, and only a few can afford to send their children to school. One of the consequences of this situation is the emergence of an uneducated generation and the occurrence of teen marriage, as a way to ease economic hardship (UNHCR 2023a).

Lebanon’s Policy Towards the Refugees

Over the years, Lebanon has pursued a vague policy towards its refugee population, with regard to arranging their status and rights. It is not a signatory to the UN convention on refugees and has not advanced significant internal legislation on this matter. The difficult political and economic situation in Lebanon, including 30 years of the presence of the Syrian army and challenges in coping with the Palestinian refugees, have to a large degree shaped government policy towards the Syrian refugees in recent years (Janmyr 2016).

In the political arena, Hezbollah’s opposition to the integration of the Syrian refugees in society, as Sunni Muslims and opponents of the Assad regime, has greatly influenced their level of assimilation. The increasing demographic weight of Sunnis in Lebanon could be translated into political power in Lebanese parliamentary democracy, in which each religious denomination is allocated a predefined number of representatives in each governorate, which reflects the size of the population. This concern threatens the political power of Hezbollah, which is Shiite. Hezbollah also supports the Assad regime and publicly assisted it during the war in Syria starting in 2013; thus most Syrian refugees oppose the organization and have even acted against it over the years (Thibos 2014).

Meanwhile, there was a change in Lebanese policy starting in late 2014 and early 2015, led by Hezbollah, with the refugee issue having become a central pillar in the country in a process called securitization —the conceptualization of the phenomenon as an existential threat in a way that creates a justification for using exceptional measures— (Wertman and Kaunert 2022). An attempt was made by Lebanon’s political elite to keep the Syrian refugees away via strict policies, restrictions at border crossings and increasing the tension between the populations (Secen 2021). Thus, in October 2014, the Council of Ministers of Lebanon adopted a policy aiming to reduce the number of Syrian refugees in the country by limiting access to its territory and encouraging them to return to Syria. Starting in January 2015, the Lebanese regime enacted several measures to implement this policy. They included a requirement to present an official declaration from the authorities in Syria on the purpose of a person’s entry to Lebanon when crossing the border, without the possibility of registering as refugees or receiving protection from the Lebanese state. According to this legislation, Syrian refugees who register with UNHCR are obligated to sign an agreement in which they commit not to work during their time in Lebanon. This is contrary to international law, which determines that refugees must be allowed to register as refugees and to receive protection, and also states that refugees must be granted the possibility of working in the country of asylum (Kheshen 2022).

The prohibition on registering the Syrians as refugees remains in force and has greatly affected their degree of integration in the Lebanese population. Without designated entry visas to Lebanon, Syrian refugees are considered illegal immigrants. Many of the refugees did not carry out the required process before entering Lebanon, and the majority of the refugees who did so cannot pay for the annual renewal of the visa, at a cost of hundreds of dollars (their alternative is to return to Syria and to re-enter at the border). As of 2022, about 83% of documented refugees were staying in Lebanon illegally (VASyR 2022). The lack of legal status renders the refugees extremely vulnerable. They are exposed to exploitation and to a lack of regular income and are at risk of imprisonment and deportation due to illegal employment. This also places severe limitations on their movement, as well as limitations on access to services, especially medical care (NRC 2014). Given the prohibition on receiving work permits, the refugees can register as migrant workers via sponsors or through an employment contract. In this framework, they can only work legally in the environmental, agricultural, and construction industries, which greatly limits their ability to find employment and to earn a living (Baroud and Zeidan 2021). A study by the aid organization Oxfam reveals that Syrian refugees working in the framework of a sponsor permit will work for wages below minimum wage, and below the wages of Syrian refugees employed illegally (Leaders for Sustainable Livelihoods 2019).

The Effect of Economic Collapse on the Perception of Refugees as a Burden

Since 2020, Lebanon’s situation has deteriorated due to an economic crisis and failed leadership, which suffers from political disfunction. The lethal explosion at the Beirut port and the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the crisis, followed by the war in Ukraine, which rocked the global economy. As of 2024, Lebanon is a bankrupt country, in which 80% of the population live below the poverty line, there is a severe shortage of basic goods and electricity, and the country’s infrastructure—with respect to water reservoirs, the health system, social assistance, and sanitation— is greatly strained. The unemployment rate in Lebanon has more than doubled, from 11.4% in 2018-2019 to about 30% in 2022. This situation has increased the tension between the Lebanese and the Syrian refugees, who are blamed for the situation. Serious conflicts have developed between the local population and the refugees due to competition for employment, with an emphasis on jobs that do not require employment experience (Government of Lebanon and United Nations 2023).

The result is a rise in racist attitudes towards the refugees, which reached the point of physical violence. UNRWA, the UN aid agency responsible for the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, expressed great concern at the discrimination and restrictions enacted against both the Syrian and Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. For example, in 2022, there were numerous reports that the shortage of wheat due to the war in Ukraine led to a situation where bakeries around Lebanon created two lines for buying bread—a line for Lebanese citizens, who received priority, and a separate line for the Syrian refugees, who were forced to wait for hours. Similar to the Turkish case, the economic and political challenges led official figures from throughout the Lebanese political spectrum to intensify their opposition to the refugees’ presence in Lebanon, to more firmly call on the international community to help repatriate them to Syria, and to demand the advancement of restrictive measures on their lives in order to encourage them to leave (Barjawi 2022).

In July 2022, Nadim al-Jamil, a member of parliament representing the Phalanges Party, declared that repatriating the Syrian refugees is not a matter of choice but a national necessity. “If Syria is not safe for them, their presence here is not safe for the Lebanese, as indicated by recent events. Either they return or they will be returned” (Al-Mahmoud 2022). Prime Minister Najib Mikati threatened that if Western countries do not cooperate in repatriating the Syrian refugees in Lebanon, Lebanon would get them out through legal means. In August 2022, an official announcement was published by the government of Lebanon according to which the country’s authorities could not host more than a million Syrian refugees and that the government intends to repatriate 15,000 refugees each month to Syria, in coordination with the Syrian regime. This was based on the claim that, with the cessation of the battles, many areas in Syria had become safer to live in (Barjawi 2022). Issam Sharaf al-Din, Lebanese Minister of Displaced Persons, justified the policy by estimating the annual cost of keeping the Syrian refugees in Lebanon at approximately three billion dollars, and claiming that the country cannot afford this given its economic situation. As for the estimated tens of thousands of political refugees, Sharaf al-Din said that the UNHCR should ensure their transfer to a safe country, in accordance with international laws and conventions (Barjawi 2022).

UN figures warned that if Lebanon repatriated the Syrian refugees against their will, it could be subject to international sanctions, including the termination of all aid originating from the UN and other international institutions (Al-Dahibi 2023; Bouloss 2022). Nevertheless, as early as 2013, Hezbollah held negotiations with the Assad regime regarding the deportation of the refugees back to Syria, and in 2017 it deported the first wave of tens of thousands of Syrian refugees to northern Syria, apparently as a result of negotiations that it held with opponents of the Syrian regime (Estriani 2019). Starting in April 2023, after years of pressure from Hezbollah, unofficial sources have reported the forced deportation of tens of thousands of Syrians by the regime in Lebanon. According to the reports, the Lebanese army carries out raids in unofficial camps where refugees live and arbitrarily deports them (European Union 2023). Official accounts claim that all of the repatriations were voluntary, but testimony received by Human Rights Watch contradicts this claim. In addition, Human Rights Watch emphasizes that the Syrians that have remained in Lebanon live in fear of arbitrary deportation, and it has been revealed that the government of Lebanon does not individually examine their situation before deporting them, contrary to international law. An example of this is the report on the deportation of former Syrian army officers, who were reportedly exposed to torture and abuse after their return to Syria due to having deserted the army (Human Rights Watch 2023). Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati declared in September 2023 that thousands of Syrian refugees were trying to “illegally” enter Lebanon each month. In his statement, Mikati emphasized the severe economic damage and the threat to Lebanese demography resulting from the Syrian refugee crisis. Thus he justified his government’s policy of not allowing additional refugees to enter the country and deporting the refugees living in it (AP 2023).

Syrian Refugees in Jordan

After the onset of the civil war in Syria, Jordan helped the moderate opposition organizations, in particular the Free Syrian Army. In this way Jordan contributed to the rebels’ struggle in southern Syria, while providing supporters of the opposition with access to Syrian territory via the border between the countries. However, compared to the other Sunni countries (chiefly Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia), Jordan was less dominant in its support for the struggle against Assad, apparently out of caution regarding the regime and its supporters. Once the momentum of the war reversed in favor of Assad, Jordan reverted to recognizing the regime and abandoned its efforts to support its opponents, in order to avoid direct conflict between the countries (Rabinovich and Valensi 2020).

Alongside the aid to the rebels, Jordan opened its gates to thousands of refugees who fled from the combat zones in Syria. According to Jordanian government estimates, about 1.3 million Syrian refugees who arrived since the outbreak of the crisis in 2011, are living in the kingdom (The Jordan Response Platform n.d.(, of which about 660,000 are registered with the UNHCR. About half of the Syrian refugees in Jordan are from the Daraa Governorate, in southern Syria, which borders northern Jordan. Most of the Syrian refugees in Jordan live in towns and villages among local communities. About 17% live in the two main refugee camps, Zaatari and Azraq. The Syrian refugees prefer to find asylum in the local communities rather than the refugee camps, partly due to better employment opportunities.

The Zaatari refugee camp was established in July 2012 and serves as the temporary home of about 80,000 people. Many of the camp’s residents suffer from poverty and instability, child labor and child marriage is rife, and there is no guaranteed access to education. The children live in unsanitary conditions, generally in mobile homes (25,000 caravans), in a crowded desert region located about 20 kilometers from the Syrian border.

Humanitarian support for the refugees in Zaatari is under the joint responsibility of the Jordanian government and the UNHCR, with about 1,200 employees from 32 different international and Jordanian organizations operating in the camp. However, the humanitarian aid is not continuous, and in 2022 the UNHCR did not receive the 40.9 million dollars of funding intended for aid for 391,400 Syrian refugees (106,622 families). The UNHCR warned of a humanitarian crisis among the Syrian refugees in Jordan due to funding problems, and noted that as a result, there was a decline in the food security of the refugees and an increase in children dropping out of school. Aside from the nutritional issue, housing conditions are also not adequately addressed. After the camp was established, thousands of caravans were provided to house the refugees, to replace initial supplies of tents. According to the UNHCR, the lifespan of these caravans is six years, but they have been there for over eight years (Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 2022).

The Azraq refugee camp, which was established in 2014, houses about 40,000 refugees, about 60% of them children. In a survey conducted by the UNHCR in the camps at the end of 2021, 83% of families in the Azraq camp reported being in debt (70% of them stated that the main reason for this was loans to buy food), and about 50% of the population that was surveyed at the camp reported at least one chronic illness among their family members. Moreover, about 60% stated that they were experiencing a certain level of depression (compared to about 40% who reported this at Zaatari) (UNHCR 2022b). However, it seems that the living conditions at Azraq are slightly more reasonable than at the Zaatari camp, perhaps because it houses fewer refugees. The camp’s residents reported about 11 hours of electricity per day (compared to slightly under 10 hours per day reported at Zaatari). At the Zaatari refugee camp, during the second quarter of 2023 there was a sharp decline of 30% in the number of families whose water supplies met their needs.

When it comes to employment possibilities, most of the residents of Azraq work in the camp, while at Zaatari more work outside of the camp, where they consequently face greater workplace hazards. While child labor at Azraq was reported at twice the rate of Zaatari, children at Zaatari had much greater exposure to dangerous jobs and incidence of school absence due to work. In addition, child marriage was reported as more common at Zaatari than at Azraq (UNHCR 2022b). A 2023 survey conducted by the UNHCR among registered Syrian refugees reveals that 90% of the refugee families at both camps are in debt, and the majority of the sources of income of these families came from humanitarian aid (UNHCR 2023d).

Among the refugees who live in local communities rather than in the refugee camps, poverty rates are very high. According to a 2018 UNICEF report, 85% of Syrian children in Jordan live below the poverty line. 94% of the children aged 5 and under do not have access to at least two of five groups of basic needs. About 40% of the families are coping with food insecurity, and another 26% of the families are at risk of this (UNICEF 2018).

A survey conducted by the UNHCR in February 2023 regarding perception of their situation in the host countries, found that 86% of Syrian refugees in Jordan had insufficient income to cover their basic needs and those of their family members. The refugees stated that housing and basic goods were significant challenges. Furthermore, a high percentage of the respondents expressed an intention to move to a third country, especially in order to improve their living conditions, reunite with family members located in another country, or for studies (UNHCR 2023b).

Despite their difficult situation, Syrian refugees in Jordan do not display a desire to return to their home country under the current conditions. From 2019 to 2021, about 41,000 refugees voluntarily returned to Syria from Jordan, constituting only about 5% of the refugees registered with the UNHCR (Sharayri 2022). According to a survey conducted by the UNHCR in January 2023, 38% of the refugees are interested in returning within five years, but only 0.8% are interested in returning within a year (the lowest figure among the refugees surveyed in countries in the region, and a decrease from the figure of 2.4% that was recorded half a year earlier). However, it should be noted that 65% of Syrian refugees in Jordan still expressed hope to return to their home country in the future, whether in the next five years or afterwards. Among all the countries where the survey was conducted (Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, and Iraq), the highest figures regarding this aspiration were recorded in Jordan.

Jordanian Policy Towards the Refugees

From the beginning of the crisis, the government of Jordan took on responsibility for absorbing the Syrian refugees and allowed them to integrate deeply in society compared to other countries in the region. In 2014, Jordan established the Syrian Refugees Affairs Directorate in the Ministry of Interior, which became the main governmental body responsible for coordinating and coping with the refugee issue in Jordan. Starting in 2015, the government has published the annual Jordan Response Plan—a strategy to cope with the refugees and strengthen the ability of the refugees and of the local population to cope with the situation (UNHCR 2017). According to the UNHCR, the Jordanian government dedicates greater attention and resources to Syrian refugees than to other refugees in the country.

Unlike the aggressive and sometimes racist attitudes that emerged in other host countries, it seems that Jordan maintains a more moderate stance towards the refugees. Official figures have even declared that the kingdom is morally responsible for the refugees and that their departure should only be voluntary, on the condition of a political climate that can assure their safe return to Syria. Meanwhile, in the Jordanian case too, the authorities place pressure on the international community to help the Syrian refugees, so that Jordan will not be forced to cope with them on its own.

Similar to their government’s attitude to the Syrian refugees, the Jordanian population also views them positively. Since October 2020, the UNHCR has conducted periodic surveys among the Jordanian population. The latest survey, which was conducted in June 2023, shows that the local population’s support for the refugees in Jordan is still strong and stable, although there is some recognition of the consequences of their presence for the Jordanian economy (UNHCR 2023c): 96% of those surveyed expressed support for the refugees and 78% claimed that they support the refugees’ integration in the community. These figures have remained stable in the surveys. About 90% of those surveyed claimed that there is coexistence between the Jordanian population and the refugees in the country.

At the same time, the Jordanians are aware of the implications of the refugee issue for the country’s economy and for their prospects: almost half of those surveyed claimed that the refugee’s presence has an economic impact on their personal or family situation. 56% of them claimed that this influence was very negative (an 8% increase from the previous survey, which was conducted in November 2022), and another 39% claimed that this influence was somewhat negative. In light of this, 89% claimed that the government’s response to the refugee issue was sufficient, 60% thought that the refugees receive more aid than the country’s citizens, and 61% claimed that too much money is allocated to refugees in Jordan. Many believe that the refugees should return to their home country, but about 62% claimed that the decision on the refugees’ return should be made by the refugees themselves—a slight increase compared to previous surveys.

The relatively positive approach adopted by Jordan towards the Syrian refugees is evidently related in part to ethno-demographic circumstances: most of the Syrian refugees who arrived in Jordan are Sunnis, like most residents of the kingdom. Furthermore, some of them are members of families or tribes that were located on both sides of the border (Musarea 2019). A considerable portion of the Syrian refugees in Jordan are from southern Syria, from areas close to the border with Jordan, and residents of northern Jordan are sometimes related to them by blood. With the onset of the war, many members of these tribes fled Syrian territory via the Jordanian border (Miettunen and Shunnaq 2020).

Despite the attitudes of the public and the leadership regarding the refugees, the hosting of the Syrian refugees has widespread economic consequences for the kingdom. In the first few years of the crisis, it was reported that about 160,000 Syrian refugees were working in Jordan, while the unemployment rate among Jordanians was about 20%. At the beginning of 2018, the government of Jordan estimated the cost of absorbing the refugees since 2011 at around ten billion dollars. That year the amount of international aid to Jordan stood at around 1.7 billion dollars (Eran 2018). The increasing number of refugees over the years has exacerbated the state of unemployment and poor infrastructure and the serious water crisis in Jordan, all of which were already precarious before the refugees arrived.

In this context, since 2022 there have been increasing complaints from government figures about the economic and social burden that the Syrian refugees constitute for Jordan. In May 2023, the government announced the “Jordanian initiative” to end the crisis in Syria, which includes a plan to voluntarily repatriate the refugees (Akour 2023). This initiative reflects a change in the Jordanian government’s attitude towards the refugees and indicates its intention to encourage their repatriation or departure from the kingdom. Meanwhile, akin to the policy enacted in Turkey and Lebanon, the kingdom started to deport Syrians back to their country, contrary to the principle of non-refoulement in international law. So far there have been reports of the deportation of dozens of Syrian refugees, and this policy is expected to expand in the future with the warming of relations between Jordan and Syria (SOHR 2024b).

Syrian Refugees in Egypt

In Egypt about 150,000 Syrian refugees are registered with the UNHCR as of January 2024. The Syrian refugees first arrived in Egypt in 2012, with the intensification of the civil war in Syria. In response to the large stream of refugees, the UNHCR opened an office in Alexandria in December 2013. As of 2015, the number of unregistered Syrian refugees was estimated at about 170,000. According to the UNHCR, most of the refugees in Egypt live in urban areas, with an emphasis on the regions of Cairo, Alexandria, Damietta, and along the northern coastal strip (UNHCR n.d.-c).

Egyptian Policy Towards the Refugees

The Egyptian position on the war in Syria in general and towards the Syrian refugees in Egypt in particular has differed considerably between Mohamed Morsi’s presidency and that of the current president, El-Sisi. Morsi, who was identified with the Muslim Brotherhood movement, clearly supported the opposition to the Assad regime and in particular the Islamist organizations. In 2013, this support even reached the point of threatening to send a volunteer military force to Syria, but Morsi was ousted from power not long afterwards. El-Sisi, who persecuted Muslim Brotherhood members upon coming to power, held a different position on the internal war in Syria and was much less opposed to the Assad regime (Rabinovich and Valensi 2020).

The shift in position on the war in Syria was also reflected in Egypt’s attitude towards the Syrian refugees. At the beginning of the crisis, the Syrian refugees were permitted to enter Egypt without a visa. Former president Morsi declared during his presidency that Syrians in Egypt were not obligated to renew their residency status, but he did not issue a presidential order on the issue. Thus, when Morsi was ousted from power, those Syrians who did not renew their status found that their presence in Egypt became officially illegal. Moreover, the country’s authorities linked the Muslim Brotherhood to the Syrian refugees (some of whom did identify with it) and began to perceive the refugees as a threat.

Since July 2013, hundreds of Syrians have been arrested and deported because they did not have suitable residency documents permitting them to remain in Egypt. Some of them were held in prisons under harsh conditions for an indefinite period. Moreover, even though many Syrians have succeeded in finding work in Egypt, this remains a major challenge for others, given the government’s reservations about providing the refugees with access to the labor market. Many of them have integrated into the Egyptian black market and are working illegally, without rights or insurance. Many refugees claim that the Egyptian authorities’ attitude towards them has changed substantially since they arrived in the country. In addition, Palestinian refugees arriving from Syria are also not authorized to register at the UNHCR, in light of a request by the government of Egypt at the beginning of the crisis in 2012 (Abaza 2015).

Access to educational institutions is also limited for the refugees’ children. In 2012 Egypt decided to allow the children of the Syrian refugees to access public schools and to register for universities without paying, but in 2016 it did not officially renew the decision, and many universities interpreted the non-renewal as a cancellation of the government subsidies for the Syrian refugees’ tuition. In addition, many refugees complained that various bureaucratic issues make it difficult to register their children for public schools, and there were reports that certain schools rejected refugee children. At schools where Syrian refugees did attend, on more than one occasion there were reports of violence against them, including by teachers. There were also reports that students dropped out of school because of financial problems (ElNemr 2016).

There is evidently a gap between the actual living conditions of the refugees and the way they are perceived by international organizations, chiefly the UN, which tends to praise the attitude of the Egyptian government and population towards the refugees in Egypt (UNHCR 2020). According to the UNHCR, the Syrian refugees have access to the public education system like Egyptian citizens (UNHCR 2023e). Furthermore, the UNHCR praised the government of Egypt for implementing strategies and plans for the digital transformation of the country’s public schools, given the fact that these programs also include the children of refugees and asylum seekers in the country’s public education system. When it comes to health services, according to the UNHCR, the refugees and asylum seekers in Egypt are entitled to public health services and are included in national health initiatives equally with citizens. During the COVID-19 crisis, despite a limited supply of vaccinations, the refugees had equal eligibility to citizens (Beshay 2021).

Egypt is an active partner in initiatives to resettle the refugees. In this framework, through the UNHCR, some are resettled in third countries such as European countries, Canada, Australia, and the United States. At the end of 2022 the UNHCR reported that during that year 3,234 refugees that had been in Egypt were resettled in several countries (UNHCR 2022a, 2022c).

Syrian Refugees in Iraq

The Syrian refugees are only one part of the problem of refugees and displaced persons in Iraq, which stems mainly from the war against ISIS over the past ten years, and from the conflicts and instability that have existed in the country for decades. According to UN figures, about 1.2 million people are still defined as internally displaced persons, while about 280,000 in Iraq are registered as refugees (UNHCR n.d.-b). Most of the refugees and displaced persons in Iraq are concentrated in the Kurdish autonomous region in northern Iraq —where more than a million Iraqis fled to escape ISIS (World Vision n.d.). In addition, out of the approximately 260,000 Syrian refugees in Iraq, the majority apparently come from the Kurdish areas in eastern Syria, and about 90% of them are located in the Kurdish region of Iraq where there are nine refugee camps (UNHCR n.d.-a). Nevertheless, most of the Syrian refugees live in urban areas.

In 2021, a decade after the start of the crisis in Syria, UN agencies reported about 250,000 Syrian refugees and asylum seekers in Iraq, with deteriorating humanitarian conditions. Like the Syrian refugees in other countries in the Middle East, in Iraq too there have been reports of increased incidents of child labor and child marriage. Moreover, about 60% of the refugee families in Iraq attested that they had reduced their overall consumption of food and that they were in debt. Almost a third of the families, according to UN figures from 2021, relied on humanitarian financial aid.

The accessibility of medical and educational services for the Syrian refugees was to a large extent undermined by the COVID-19 crisis, while the risk of food insecurity increased. Fewer than half of the Syrian refugee children who were registered in educational frameworks before the pandemic continued to participate in learning activities from home while schools were closed (UNICEF 2021).

According to UN figures from 2022, about 86% of the Syrian refugees living in refugee camps in Iraq were coping with food insecurity or at risk of it. In addition, according to the figures, the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis for the state of unemployment and for the Iraqi economy, as well as the consequences of the war in Ukraine on price increases, harm many refugees’ access to basic food products. This situation causes many families to adopt problematic coping strategies such as increasing debts, selling assets, child labor, and children dropping out of school in order to support their family’s livelihood (United Nations 2022).

Iraqi Policy Towards the Refugees

It seems that the Iraqi government’s attitude towards the Syrian refugees and towards displaced persons in its country is sorely lacking (Oxfam Denmark n.d.). In the first few years of the civil war in Syria, it resisted the absorption and integration of the refugees in its territory. Iraq was subsequently subject to criticism for the number of Syrian refugees that it took in, which was low compared to other countries neighboring Syria. In certain cases, there were also reports of the government’s hostile attitude towards the refugees absorbed in Iraq, due to the concern that some of them belong to extreme Islamist organizations and concerns about their influence on the Sunni minority in Iraq and on the stability of the Iraqi government. In this context, reports revealed that while refugees were ostensibly housed in designated centers, in practice they were imprisoned in these centers (New York Times 2012).

It is worth mentioning that the Kurdish autonomous region in Iraq is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, and its laws do not contain reference to the status of refugees who have fled from conflicts or from persecution and seek asylum within it. The autonomous government designated crossings for Syrians wishing to cross the border into its territory (Majed n.d.), but sometimes closed its borders when the volume of Syrian refugees peaked, especially during the first few years of the civil war. However, the Kurdish identity of most of the Syrian refugees in the region contributed to a sense of solidarity between the refugees and the local community (NRC and Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion n.d.). Following the Turkish invasion of the Kurdish areas in northeastern Syria in 2019, another wave of refugees of Kurdish origin arrived in the Kurdish region in Iraq (Intersos Humanitarian Aid n.d.).

Repatriation of Refugees to Syria

Questions of rehabilitation, political arrangements, and reconciliation in the era after the war in Syria are all interconnected. The Western position led by the United States stipulates three conditions for economic aid: political reform, the establishment of a legitimate regime in Syria, and the repatriation of the refugees. Assad’s opposition to real political reform and his unwillingness to repatriate a large portion of the refugees impede the conditions for rehabilitation.

When it comes to the refugees, officially the regime expressed support for their repatriation, but in practice this offer lacks substance. Former Syrian foreign minister Walid Muallem declared as early as October 2018 at the UN General Assembly that “there is no longer a reason for the refugees to remain outside of Syria. The doors are open for all Syrians abroad to return voluntarily and safely” (Al Yafai 2018). This contrasts sentiments expressed by Syrians close to the regime, who made it clear that it would be better for the refugees to remain outside of Syria. In their view, the refugees are former rebels or have the potential to rebel against the regime. Assad’s loyalists said that a limited population in Syria with a greater proportion of Alawites is preferable to the repatriation of the Syrian refugees. According to the then head of Syrian Air Force Intelligence Directorate, Jamil Hassan: “Syria with 10 million trustworthy people who comply with the leadership is preferable to Syria with 30 million vandals” (Al-Hassan 2018). And indeed in 2010 the Syrian population numbered about 21 million residents while in 2019 it numbered 17 million, while given the departure of the mostly Sunni refugees, the Alawite minority’s portion of the population (to which President Assad belongs) increased from 10% to 17%. Assad himself related to the issue, although more moderately, and stated that “we have lost the best of our young people, and our infrastructure has been damaged […] but in return we have earned a healthier and more harmonious society” (Al-Asad 2017).

Ironically, Russia, the regime’s ally, has a position similar to that of the West regarding the repatriation of the refugees. In its view, the refugees could be an important workforce in the process of rehabilitating Syria, a catalyst for humanitarian aid, investments, and encouraging normalization with other countries in the region.

Towards the end of 2017, when calm was achieved in large parts of Syria and it seemed that the war was approaching its end, tens of thousands of refugees began their return to Syria, mainly from Lebanon and Jordan. In both cases this stemmed from pressure applied by the government of Jordan and Hezbollah in Lebanon on the Syrian refugees to return home. After Hezbollah, alongside the Lebanese army, succeeded in taking control of the Arsal mountains on Lebanon’s border with Syria, it started to push about 100,000 refugees from the region to return to Syria (Zisser 2020). That year media and political pressure also increased regarding the Syrian refugees’ voluntary return to their home country. After 2022 and given the deepening of the economic crises, the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and basic hardships that intensified, the host countries were less able to cater for the refugees. Incidents of violence and intolerance towards the refugees increased and a small portion returned to their home country.

According to UN reports published over the years, about 750,000 refugees have returned to Syria since 2016. The majority of them (500,000) returned from Turkey to regions under the control of the opposition in northwestern Syria following the Turkish military operation against ISIS in 2016 and against the Kurds in 2018. From January to October 2022, 43,254 people returned to Syria. This is a small percentage of the total number of returnees since 2016, and a very tiny percentage of all Syrian refugees. According to UNHCR figures, 29,501 refugees returned from Turkey to northwestern Syria, while 7,087 refugees from Lebanon and 3,679 refugees from Jordan returned to areas controlled by the regime.

The figures indicate that Syrian refugees are not in a hurry to return to Syria, despite the fact that in most of the host countries they do not enjoy freedom of movement and have limited access to nutrition, education, and medical services. According to UN surveys, their non-return to Syria is due to several reasons: First and foremost, concerns about living conditions in Syria, which make it difficult to obtain employment security; a lack of personal security, including fearing for their lives and fearing acts of revenge by the Syrian regime, as they could be seen as a disloyal population (partly based on reports of imprisonment and torture of refugees who returned to Syria); a shortage of proper basic services, an inability to return to their homes because they have been completely destroyed, or if they lack proof that these are indeed their homes; and the destruction of the country’s infrastructure.

A survey conducted in September 2023 that examined the refugees’ positions regarding their intention to return to Syria shows that the majority of the refugees still hope to return to their home country sometime in the future: 93.5% of those surveyed claimed that they do not intend to return to Syria in the coming year. More than 50% are not interested in returning even in five years, and 43.5% are not interested in returning at all (compared to 40.6% who are interested in returning) (UNHCR 2023b).

Refugee Repatriation Mechanism

Despite the widespread reluctance of the refugees to return to Syria, some of them choose to return to their home country. Their choice does not stem from a real willingness but is mainly due to the harsh living conditions and their disgraceful treatment in the host countries. In most cases the returnees are elderly, women, and children, as young men fear for their fate if they are identified as opponents of the regime or as a disloyal population. Thus, many choose to remain in the neighboring countries or to risk their lives and try to flee illegally by sea.

Despite the desire to repatriate the refugees in order to reduce the burden on surrounding countries, the international community has not arranged for official guarantees from the Syrian regime that would ensure the safe return of the refugees without the danger of being arrested, tortured, or forcibly conscripted. In practice, there is no orderly mechanism for this as Syria is not functioning as a unified state under one central government. While Turkey sends refugees who are interested in returning to their home country to territories controlled by the Syrian opposition in northwestern Syria, Lebanon sends them to areas controlled by the regime via official border crossings, as it does not border areas controlled by the opposition. Jordan has a similar policy aside from returning refugees to the Al-Tanf region in southeastern Syria, where American forces are present.

Despite the regime’s agreement to repatriate some of the refugees, there is no supervision or control of their safe return to Syria, mainly due to lack of coordination between the agencies in Syria and those in the host countries. There are reports of arbitrary and illegal arrests and incidents of rape and sexual violence towards returnees. Amnesty International has defined the repatriation of the refugees to Syria as a death sentence (Amnesty International 2021).

The regime’s official policy states that there are groups that it prioritizes for resettlement in Syria, so refugees who are interested in returning to rural areas, especially in the area of the Homs and Damascus suburbs, and not to urban centers, are welcomed. The prioritization is related to the regime’s limited ability to provide basic services such as electricity, transportation, health, and education. Settling the refugees in cities would increase the strain that already exists on the infrastructure and minimal services that have been provided in recent years in Syria, due to the fuel crisis and the electricity shortage. The villages are less crowded, and there the refugees’ integration in agricultural activity as a place of employment could actually contribute to the production of wheat, fruit, and vegetables, and thus improve the residents’ food security.

Over the years the regime has adopted a series of laws intended to place pressure on the refugees. Some of them relate to ownership of real estate, such as Decree 66 from 2012 and Law Number 10 from 2018 (Human Rights Watch 2018). These laws apply in cities, and they aim to enable the expropriation of property from those who cannot prove their ownership of their property, especially in cases where the registered owners of the asset do not live in Syria. Moreover, the regime has the right to expropriate the property of a man and his family members if he has not fulfilled his obligatory military service before the age of 43. Consequently, men must pay an 8,000-dollar fee for exemption from military service or return and enlist before the specified age (AlMustafa 2023).

Furthermore, in the absence of owners, the Assad regime leases agricultural lands that belong to refugees or displaced persons in Syria through public tenders. This policy was adopted in 2019 and is implemented in the rural areas of Hama and Idlib, after the regime restored its control there. This illustrates how the regime exploits refugee assets, including confiscating or renting their property or indirectly forcing them to return, as part of a selective refugee repatriation policy that the regime is trying to implement.

Assad’s policy towards Syrians who left the country before the civil war in 2011 is completely different, and actually encourages their return to Syria. This population, which is not seen as hostile to the regime, often receives offers from official figures to invest in regions controlled by Assad. The regime lures them through assistance with investment projects, especially in the services and tourism sectors, that constitute another source of income for the state, as they create new work opportunities and contribute somewhat to rehabilitating the country.

In the case of the return of certain refugees from Lebanon, Turkey, or Jordan, the regime exploits the opportunity to appear as though it welcomes their return, but in reality a selective repatriation policy pursues political interests rather than reconciliation. Meanwhile, in denying the repatriation of many refugees, the regime places increasing pressure on the host countries, which are already suffering from political and economic crises and from various security threats.

Conclusion and Implications

The Syrian refugee crisis has weighty political, social, economic, and security consequences for the Middle East. In most cases, the refugees have not been optimally absorbed in the host countries and they suffer from a lack of personal security, economic hardship, and poor sanitary conditions. Aside from the economic difficulties that the Syrian refugees are experiencing, they are exposed to various forms of exploitation, from child labor to sexual violence and recruitment into armed organizations or criminal organizations. There are numerous reports of the operation of organized crime networks in refugee camps and in areas where refugees live, including Syrian refugees, in Jordan and Lebanon, as well as in Germany and the UK (AFP 2018; Miles 2013; Townsend 2023). The refusal of host countries to recognize refugee status causes major limitations on refugees’ freedom of movement, raises difficulties and restricts access to state services, with an emphasis on medical services, assistance with food, and access to education, and exposes the refugees to exploitation and abuse (NRC 2014).

In Lebanon and Turkey in particular, Syrian refugees are coping with hostile government policy and negative public attitudes towards them. The opposition parties in Turkey long ago made the Syrian refugee issue a main component of their agendas, while encouraging anti-Syrian sentiment. President Erdogan abandoned his government’s friendly rhetoric and in 2022 committed to sending a million refugees back to northern Syria. In Lebanon, the Syrian refugees have coped with a rise in arbitrary deportations, including Lebanese army raids of refugee camps. While the Syrian refugees in Jordan receive better treatment from the government and greater support from citizens, possibly due in part to the composition of the local population in the kingdom, which includes many Palestinian refugees, this does not ease the economic and humanitarian difficulties that the Syrian refugees face.

A decade of hosting refugees in countries in crisis and a limited willingness on their part to absorb the refugees properly have led to large-scale impacts on the resilience and stability of the host countries in the Middle East. While the depth of the economic crisis of the host country cannot be blamed on the presence of the refugees, especially in the case of failed states such as Iraq and Lebanon, this study has proven that the refugees are a convenient focus of blame for the economic difficulties and the social and political pressures in the host countries.

It is clear that in certain cases the mass flow of refugees placed an economic burden on countries with a precarious economy. Out of despair at their circumstances or an inability to obtain the appropriate work permits, the refugees generally agree to work for low wages, under difficult conditions, and with fewer rights than their counterparts in the host communities. The enormous wave of Syrian refugees intensified the strain on the labor market and led to a shortage of jobs, alongside the strain on state services and infrastructure that caused substantial harm to the country’s ability to address the needs of the local residents. Furthermore, in countries such as Jordan and Lebanon, the increase in the cost of rent, especially in the districts neighboring Syria, is attributed to the wave of refugees (Khawaldah and Alzboun 2022). However, studies have proven that in many cases the refugees actually contributed to the local economies and attracted international support for local development, but this fact is usually ignored, both by the leaderships and by the public in the host countries.

The wave of Arab countries normalizing relations with the Assad regime, which began in 2020, stemmed to a large extent from the desire that in return for renewed recognition and rehabilitation funding, Assad would permit the safe passage of the refugees to Syria, thus easing internal pressures in the host countries. However, the normalization process has not translated into voluntary return on a significant scale due to the ongoing violence, oppression and the economic crisis that has afflicted Syria for the past five years. Thus, the despair of the countries, chiefly Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan, of achieving a solution that would lead to the safe and agreed-upon repatriation of the Syria refugees, led to a massive wave of deportations of refugees back to Syria, contrary to the basic principles of international law and with the international community failing to address the issue.

The government of Syria itself seems unwilling to receive refugees posing possible threats to its authority. The nature of the Syrian regime, which is not willing to make concessions, compromises, or civil and liberal reforms that would benefit the country’s citizens, reduces the chances of the voluntary repatriation of greater numbers of refugees in the coming years. Consequently, the pressure on the host countries, which are already suffering from political and economic crises and from various security threats, is expected to increase. While the refugees are not the ones creating the crises and are not their main cause, the public and political pressure placed on them is expected to increase. In addition, as the trend of deporting refugees grows, forced mass repatriation will lead many Syrians to try to reach Europe—which is contrary to the interests of Europe and the United States.

The international community’s indifferent attitude towards the violations of refugees’ human rights in the various countries and its inability to effectively influence the Syrian regime make it difficult to guarantee the safe repatriation of refugees and ensure continued pressure on the host countries. Despite the European Union and the UN’s attempts to provide economic aid and to condemn violations of refugee rights in the host countries, it is evident that all attempts have failed due to the lack of sustainable mechanisms that would enable the reshaping of a complex political system that is leading to a deterioration in the refugees’ condition.

This reality requires rethinking the current strategy: First, it is necessary to adopt long-term approaches and solutions while economically supporting and helping the host countries. This is different from the current aid programs, which rely on short-term funding cycles that are implemented by international non-governmental organizations that are not always coordinated with the host countries’ systems. Second, it is necessary to put forward benefits and incentives that will encourage economic growth in the host countries and also enable the creation of new employment opportunities in essential professions, especially in sectors with high levels of refugee employment. Furthermore, a teaching and training framework is needed that will provide refugees with professional capabilities and skills that will enable them to go out into the labor market. Greater involvement of local bodies and civil society organizations, which are more familiar with the characteristics of the political and social system in the country, is needed in order to ease the refugees’ integration in communities and to reduce hostility towards them. Finally, a significant effort is needed to improve the economic, security, and civil situation in northern Syria for the refugees that do want to return, in the format of an approach focused on rehabilitation and development in the area.