Strategic Assessment

Public transportation, one of the basic services provided by a modern state, is of strategic-national importance and has implications for national security. Transportation impacts individual lives, the economy, society, demography, and quality of life. These aspects are relevant to decision making at the government level and include elements in decisions taken with national security considerations. At the political level decisions must be guided by the will to serve the public interest, and should facilitate, rather than block, reforms and innovations in the field. This article emphasizes that despite the importance of public transportation and its impact on the development of the economy and, and in turn on national strength and national security, in Israel this field is characterized by ongoing market and administrative failures. In fact, the situation resembles a “march of folly,” in which decision makers operate contrary to national and public needs arising from demand, and contrary to normative professional considerations.

Keywords: public transportation, national security, market failures, administrative failures, decision making, public good, infrastructure, reform, strategy

Introduction

Public transportation, one of the basic services provided by a modern state, includes a strategic-national component. The field of “transportation” interfaces with many other areas that are relevant for decision making at the national level, such as human life, the national economy, societal elements, distributive justice, and even international relations (Spiker, 2022). The lateral impact of advanced transportation infrastructures on other areas of life makes it a vital part of national strength, which in itself is an important part of national security, and thence the links between transportation and national security.

While national security has been variously defined by numerous scholars, common to all accepted definitions are a nation’s ability to protect its citizens and the lives of its residents, and to maintain internal economic and social security (Harkabi, 1990, p. 530). Assuming that human life and socioeconomic security, as well as the quality of national infrastructures, include the benefits of transportation and are common to all definitions of national security, transportation-related issues should be considered in national security decisions.

Many countries have assessed the numerous benefits to be derived from high quality public transportation and made the necessary reforms to provide an essential public good[1] (Thomas & Bertolini, 2020). Global developments in the mid-twentieth century affected the need for reforms in transportation. Among these were population growth, rapid urbanization, globalization, and the availability of technology that flooded the roads with private vehicles, which notwithstanding their benefits to private convenience are dangerous to human life, causing road accidents and air pollution. All these and other phenomena have challenged countries, and in turn prompted broad reforms in transportation in order to provide the population with suitable tools for dealing with global innovations.

None of this bypassed Israel, yet by the end of the previous century, the Israeli government had barely responded to changes in the field. It was only in 1992 that the Rabin government began a process of transportation reform, which is still underway. Moreover, in the last three decades, public transportation has been characterized by continuing market and administrative failures, and State Comptrollers have written 15 audit reports on transportation. In 2019, the State Comptroller published a special report that examined public transportation over the previous decade, stating that public transportation is characterized by a total systemic failure: “The failures and defects in the field of public transportation are extremely significant…The government and its head must address this national problem and act to remove barriers” (State Comptroller, 2019, p. 8).

Consequently, the question is whether it is possible that decision making on transportation issues at the national level has become a “march of folly,” as defined by historian Barbara Tuchman in her book (1986), in which she illustrates the reality of countries where decision makers shape policy that is contrary to that country’s public national interest. Other questions that arise are: who are the people who created these market and government failures in Israel? Does this match the approach of Thomas Oatley, who attributes the failures to the focus of modern political economy on the benefits and individual needs of decision makers? (Oatley, 2018). Is this a case of what Christopher Pollitt and Gert Bouckaert define as the political culture of a country in which actors, interests, and mutual political, social, and economic contacts influence and design policy and reforms? (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004). Are the barriers to reform shaped by parties with economic interests in the Israeli market, as proposed by David Weimer and Aiden Vining? In their research, they describe the democratic system as an arena in which pressure groups vie for a share of the goods, and the struggle between actors directs the decision making process, which harms public interests and reinforces personal interests (Weimer & Vining, 2011).

A survey of these theories helps to analyze the Israeli reality and provide a response to the basic research questions that arise around the shaping of transportation policy in Israel. With these questions as background, the article lays the preliminary foundation for the link between transportation and national security infrastructures as the basis for further study. This article presents the development of public transportation at the global level, and with reference to the theoretical foundation, examines the tools, parameters, and concepts linked to the failures of decision makers, with an emphasis on the development and management of the public transportation system. It then presents an analysis of transportation in Israel and closes with the reasons for the flaws in the system and suggestions as to what can and must be done to improve the situation.

Background: Global Influences on Public Transportation

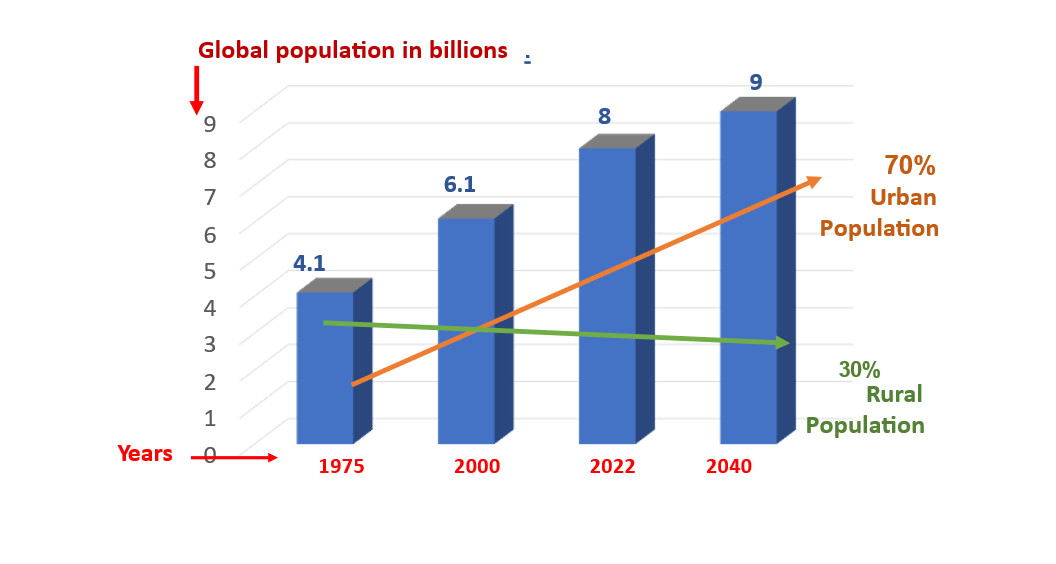

Over the last hundred years there have been several global processes that affected the development of public transportation. The first is population growth: in 1900 there were about 1.6 billion people on earth, and today there are around 8 billion. The second is urbanization: at the start of the 20th century, about 30 percent of the global population lived in cities, while 70 percent lived in rural areas, but since then the situation has been reversed (Figure 1). The result is that cities have become the main centers of trade, culture, education, and employment. An accompanying process is that of suburbanization, as the masses move from city centers to the suburbs, creating huge urban areas in which the need for convenient mobility is accepted as inherent and dominant, and this need has created an understanding in most countries that transportation is a public good (Finck et al., 2020). The third global process, globalization, has affected most countries since the 1970s. Neoliberal ideas, together with ideas from the new world of public administration, have been adopted in many democratic countries and influenced transportation. Globalization increased the need for transportation links between countries and expanded the use of private vehicles. Some countries sought to create a welfare state with distributive justice, including public transportation. In parallel, new management methods influenced public administration in the direction of reforms in the field of transportation (Drew & Ludewig, 2011; Citroën, 2017).

Figure 1. Growth of world population and urbanization trends | Source: Worldometer

A country’s transportation system demands extensive investment of resources in physical infrastructure, technological components, and institutional frameworks; this necessarily influences social, economic, and infrastructure issues, which in turn affect national strength and consequently national security. Important decisions taken at the national level bear responsibility for taking a broad, inclusive view, while implementation is the province of bureaucrats. Changes and adjustment to global changes demand comprehensive reforms. Studies on the advantages of transportation stress that considerations of human life as well as economic and social factors should be axiomatic when planning transportation policy (Carmon & Fainstein, 2013; Feitelson, 2011; Guillén, 2003).

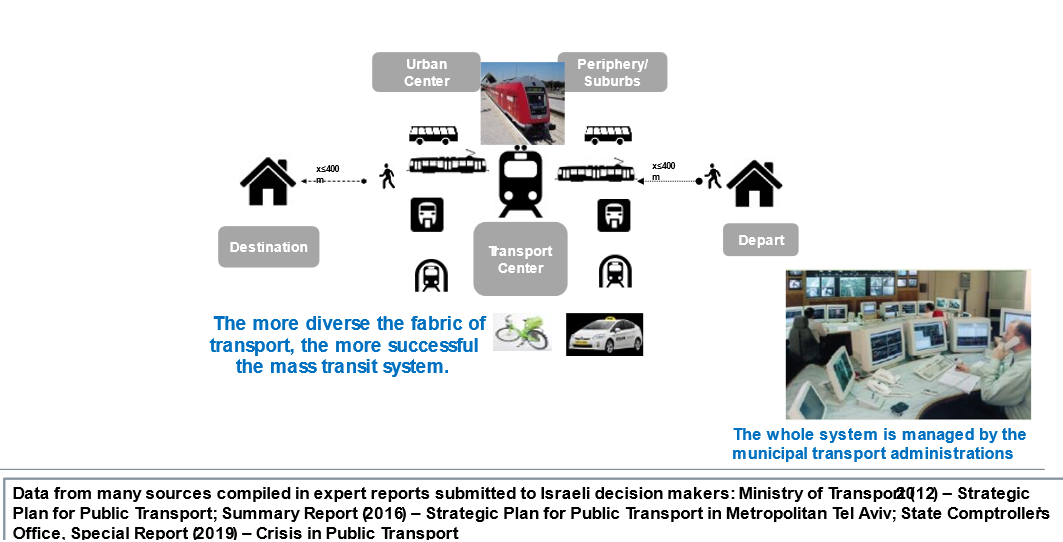

The widespread use of private vehicles in the public space is harmful (inter alia because they increase road accidents and air pollution), and the solution should be to create a situation in which public transportation is more reliable, more comfortable, faster, and cheaper than travel in private vehicles. The transportation model known as Door-to-Door (DTD) developed over the years on the basis of numerous studies (Finck et al., 2020; Thomas & Bertolini, 2020). It was submitted to the decision makers of several Israeli governments in the framework of reports from international advisors and as working papers prepared by the political echelons. Figure 2 illustrates the principle whereby an individual traveling to a specific destination uses a range of means of public transportation, operated by an urban transportation administration to reach the planned destination: the public transportation option is cheaper and more accessible than the use of a private vehicle.

Figure 2. Optimal model for reliable Door-to-Door public transportation

While this is not a perfect model, Berlin, Stockholm, Tokyo, and Singapore are just some of many cities that have adopted the elements of the model and built infrastructures for transportation centers, including fast inter-city trains, metro systems, light rails, and a wide range of bus services (Ovenden, 2004), and thus achieved the many benefits inherent in the use of public transportation.

Effects of Public Transportation

Wide use of efficient public transportation offers significant benefits on a number of levels:

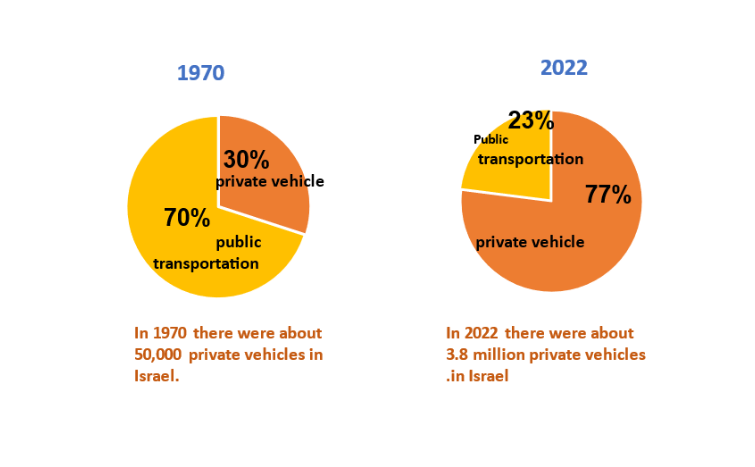

Human life: In the last 50 years the number of private vehicles has multiplied by hundreds of percent. In 1970 there were about 50,000 private vehicles on Israel’s roads, and by 2022, 3.8 million. The extensive use of private vehicles instead of public transportation has created a poor balance sheet marked by road accidents and air pollution. According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), every year on average 300-400 people in Israel are killed on the roads, while some 18,000 are hospitalized with injuries, of whom 2,000 suffer life-changing injuries (CBS, n.d.).

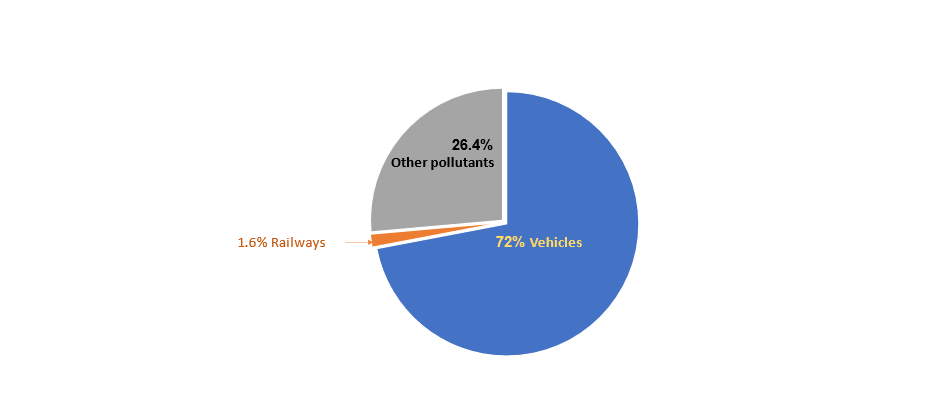

Air pollution: Travel in private vehicles increases air pollution. According to the World Health Organization, 72 percent of total urban air pollution is due to private vehicles. Other causes of pollution are shown in Figure 3. According to the Israeli CBS, in recent years an average of about 1,000 people die each year due to air pollution-related problems.

Figure 3. Average components of air pollution in urban areas | Source: Based on data from the World Health Organization

As road accidents and air pollution are a direct outcome of the growing numbers of private vehicles, the obvious conclusion is that wider use of public transportation will reduce these risks and thus save lives. For example, one train can carry about a thousand passengers (theoretically taking as many as a thousand cars off the road). According to data from Israel Railways and CBS, there are currently about 70 million journeys each year. From 2010 to 2023, Israel Railways carried millions of passengers and not one was killed. Moreover, Figure 3 shows the low rate of pollution caused by the railroads; in other words, wider use of public transportation helps reduce air pollution in urban areas.

Economic impact: Heavy traffic and the extended duration of journeys to work and elsewhere affect work productivity and lead to underachievement of potential GDP and revenues from taxation (Aviram, 2017; Maoz, 2021). Heavy traffic and traffic jams have serious economic implications. In 2018 the annual cost of congestion was defined by the Ministry of Finance as about NIS 49 billion. Treasury economists estimate that if congestion increases and there are no new conditions for public transportation, the annual cost by 2030 will be NIS 74 billion (State Comptroller, 2019, p. 545).

In addition, traffic congestion affects household expenditure with the cost of maintaining and running private vehicles. The greater the congestion, the heavier the burden on the economy. Apart from economic productivity, there is also overuse of land for roads and parking (Trajtenberg et al., 2018). Traffic congestion affects access of workers from outlying areas to their places of employment, thus damaging the efficient distribution of workers and means of stronger education in the periphery, due to problems of access by good teachers living in city centers (Ben-David, 2003).

Demographic dispersal: Efficient public transportation leads to demographic dispersal and changes the character of the social periphery. A related national security issue is the security significance of the concentration of populations, infrastructures, and resources within the metropolitan central area, as well as social and economic aspects, which in turn affect social and national resilience, a fundamental element in national security. All over the world, for example, rail transportation provides intercity travel at speeds of 250-350 kph. In a small country like Israel, fast travel between urban blocs would reduce the problems due to the remoteness of peripheral villages and development towns and help create a better balance between housing prices and the cost of living.

Security benefits: During the Second World War, residents of London found shelter in the underground Tube stations, and today in the war between Russia and Ukraine, citizens flee for refuge to underground rail tunnels. Dozens of countries that have developed underground railroads have made sure to protect the tunnels against attack in war. The rail system operating in Washington, Moscow, Tokyo, Berlin, and other cities can be locked in emergencies, and it is protected against attack by nonconventional weapons (Ovenden, 2003).

Rail transportation has also been an important element of military logistics, from the Civil War in the United States, through the First and Second World Wars, to the present: in the war between Russia and Ukraine extensive use has been made of the railraods. The logistics system of the US army includes a rail unit that takes care of infrastructures for rolling stock and is able to operate railroads independently in all situations (Magbanua, 2021).

Bilateral and multilateral connections through transportation contiguity: For overland transportation, the strategic link is clear. For example, as soon as the walls of the Eastern bloc came down, the adjustment of railroad tracks between Eastern and Western Europe was one of the first investments, to facilitate links between all regions (Citroën, 2017). In their attempts to broker peace in the Middle East, US representatives have offered aid for the construction of rail infrastructures (Indyk, 2009). Yet in spite of the global impact and all the benefits of public transportation, not all countries have realized an optimal situation.

Transportation, Public Policy, and Decision Making Processes: The Theoretical Basis

To understand what influences decision makers and what factors lead to failures in the development and management of a national public transportation system, tools and concepts from public policy literature are of major benefit. These in turn can help in an assessment of Israel’s problematic transportation situation and its essence as a government failure.

In academic research there are many theories that seek to explain government failures. The theory of public choice presents a comprehensive explanatory foundation for a wide spectrum of behaviors by leading actors in the public arena. The most prominent of the models proposed by this theory is the presentation of the democratic system as an arena in which pressure groups compete for distribution of resources, and struggles between the actors affect the decision making process contrary to the public good (Weimer & Vining, 2011). Shlomo Mizrachi and Assaf Midani state that the main motivation of politicians is reelection, and they therefore choose the options that in their assessment will earn them the most votes. Consequently, public policy cannot meet objective criteria of maximum efficiency, since the main actors are not interested in efficiency but in maximizing their personal gain, and this often creates a conflict of interest between the public that wants change and the professional echelons. Politicians prefer the status quo as long as the public does not demand a change. This dynamic partially explains why in many cases no public policy is formulated until the situation becomes catastrophic (Mizrachi & Midani, 2006).

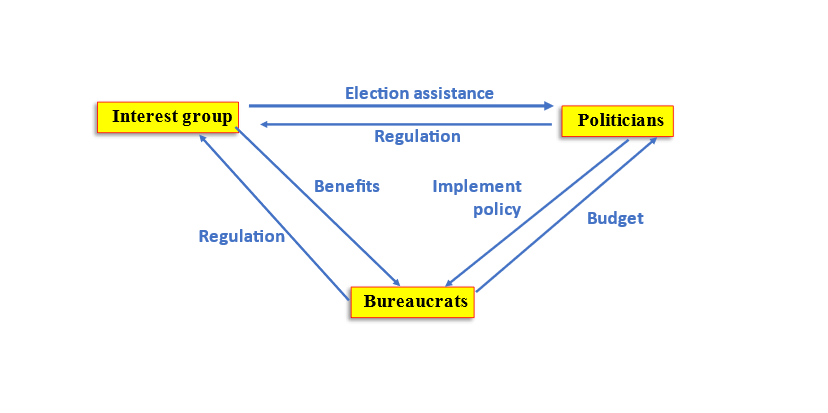

This theory is also integrated into the new paradigm on relations between state and economy, a research approach based on the claim that there is a relationship of mutual dependency between the state and the economy. The nature of this relationship and points of interface are influenced by alliances and the respective interests of politicians, professional levels, and various business sectors (Shalev, 2004). According to this theory, the conduct of the main actors is explained by the concept of regulatory capture, which refers to situations in which the regulator is a willing captive of the interests of supervisory private elements and therefore does not act properly to implement the public interests for which it is legally responsible (Figure 6). Captive regulation systematically promotes narrow interests at the expense of the public interest (Yadin, 2020; Carpenter & Moss, 2014). Regulation was created to protect supervisory bodies against competition and to ensure they fulfill their duties. In many cases, the supervised body consists of interest groups. The interest groups do not usually have absolute control of regulation, and therefore the regulators in properly run countries have a significant degree of discretion to promote the public interest.

The causes of regulatory capture can be direct and varied: bribery, threats, political appointments, election finance, gaps in information, and social proximity. The outcomes vary accordingly. Captive regulation can be extensive, but in most cases it is partial and limited (Baldwin et al., 2012).

Figure 4. Model of regulatory capture

Figure 4 shows the possibilities for influencing decision makers by virtue of their intention to be satisfied with personal benefit versus the public interest. In addition, the status of interest groups will be determined by their ability to provide the required benefits.

A thorough study of the Israeli market reveals a difficulty arising mainly from the indirect channels of regulatory capture. In particular, regulatory effectiveness is challenged by two specific features of the Israeli economy: a high degree of centralization of the private sector, and a society preoccupied with issues of peace and security (Navot & Cohen, 2015). These two singular features, economic centralization and the dominance of security concerns, affect not only economic indicators but also the ability to exert political influence and shape the agenda of narrow interest groups. The dominance of security concerns has diverted wide sections of the public from the debate on regulation, so that narrow interest groups dominate the field in the game of political influence (Rolnik & Shapiro, 2018; Navot, 2012).

A survey of the methodology for studying centralization of the economy considers factors that focus on the bargaining ability of a centralized body and its influence on policymakers. Bargaining power and extra influence can be created by possession of an essential infrastructure, which reinforces pressure when any disruption of this infrastructure will be bad for the decision makers. However, there may also be connections that reinforce the power of a centralized entity over policymakers. Such connections lie in the regulatory capture interface, which includes the fixed and ongoing relations between the centralized entity and the decision makers, politicians, and bureaucrats (Rina & Meir Heth Center, 2019).

Worldwide influences on decision makers: Several scholars agree with the claim that globalization and neo-liberal ideas as well as the theory of “new public management” (NPM) have been assimilated in Israel and created the foundation for changes and reforms in public administration (Ben-Bassat, 2001; Shalev, 2004). Globalization has spread since the last third of the 20th century and can be seen in the expansion of international collaboration, the transfer of information between countries, and the ever-increasing technological accessibility of information. All these have shaped policy that is influenced by ideas taken from other countries (Friedman, 2005).

Other studies show that globalization has been adopted as an official policy by Israel, thus shaping a new style of policy—from collectivism to liberalism. There was no move from government centralization to the transfer of additional powers to public administration, but decentralization was in the direction of transfer to the private business sector, in other words, a move from public centralization to private centralization, since decisions made by the government derive from an outlook that serves wealthy interest groups (Ram, 2006; Mitchell & Munger, 1991).

Globalization led to the free movement of knowledge, as seen for example in various professional reports (including those on transportation) from international bodies, such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, as well as the OECD and the UN. Reports of this kind are generally treated in academic research as reflecting the features of globalization that affect policy (Levi-Faur & Vigoda-Gadot, 2004). In their book, Pollitt & Bouckaert (2004) analyze the impact of decisions to make reforms in 15 different countries and identify a further influencing factor—the global economy—that has a dominant effect on policy shapers. They also stress the influences of political culture. Many studies show that reforms take place when several phenomena occur, together or separately: economic crisis, political crisis, global competition that opens a window of opportunity, or global socio-demographic change (Campbell, 2004).

Effects of political culture: In recent years, references to political culture have been marked by the new institutionalism theory, which assumes that institutions play an important and autonomous role in influencing political outcomes (Hacker, 2004; Person, 1996). Referring to different definitions of institutions, state, office holders, and more, the guiding principle is that government bodies and independent institutions influence society and are influenced by it, both formally and informally. This has a considerable impact on actor involvement, public policy shaping, government stability, reciprocal relationships, and the decision making process (Hazan, 1999; March & Olsen;1984; North,1990).

The theory on the role of institutions is not a uniform body of knowledge but a range of approaches that have developed over the last three decades. Here the focus is on two approaches that are relevant to the impact of the implementation of transportation reforms. The rational approach stresses the micro level, adopts a functional view of institutions, and highlights their role as a mechanism for creating or maintaining equilibrium. It assumes that the political and other actors involved in decision making processes act out of rational considerations in order to derive the maximum benefit for their personal interest. According to this approach, the importance of institutions lies in their ability to shape the conduct of the actors. It assumes that institutions operate according to laws that lay the foundation for connections between the actors and stress the centrality of the individual in the process of change (Hall &Taylor, 1996; Weimer, 2005; Streeck & Thelen, 2005).

In the sociological approach the basic assumption is that the institutional arrangements and customs accepted in the organizations of modern society are the result of cultural and social influences. The institutions that emerge are not built only on rational considerations of maximizing self-interest and effectiveness. Researchers in the field focus on understanding the culture and norms in public political organization, and the arrangements that became established due to social and cultural influences. Followers of this approach argue that institutional change and reforms occur because they reinforce the social legitimacy of the organization or its members (Hall & Taylor, 1996).

Engaging in reforms is important and significant due to the need to adapt public systems and infrastructures to internal and external changes. Any reform is a kind of threat that intensifies fears of change and arouses opposition from people and institutions, for whom the status quo represents convenience and political power because of their control of resources and the influence derived from their status and intention to maintain their status.

Transportation Reforms Worldwide

In view of the global effects on the need for transportation since the end of the 1970s, many countries have introduced extensive reforms. The most prominent change took place in England, where comprehensive reforms became a model for imitation elsewhere. After Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979, the economic steps led by her government were support for liberalism and a free market economy, and the result was wide-ranging privatization of government corporations.

Privatization included two very significant elements in the world of transportation. One was a curb on the dominance of the unions and greater representation of the private sector. The second was the principle that was dubbed “the golden share,” which left the state with a veto over decisions in some privatized companies (Harris, 2020; Evans, 2013). In the early 1980s, the Thatcher government fully privatized all the government's public transportation companies. With buses, the success was partial, and the government managed to improve its control with subsidy payments. In rail transportation, privatization was a complete failure (Larkin & Larkin, 1988). Thanks to globalization and collaboration in European countries, the lessons from England were translated into more effective reforms in most of the European market.

What were the main changes of the 1980s? For buses, governments adopted the free market principle, and instead of public government corporations, most countries allowed private companies to enter the transportation market by defining operating regions, renouncing central management, and facilitating the establishment of metropolitan transportation administrations. The achievements were competition between companies, lower prices, improved service, and better control of subsidy payments (Thomas & Bertolini, 2020).

For rail transportation, the lesson learned from England was mainly to avoid the complete privatization of government companies, which in Europe were mostly monopolies, and move to tenders for concessions—BOT (Build, Operate, Transfer) and PPP (Public Private Partnership). For the public administration, this meant collaboration with the private sector, granting the right to execute an infrastructure project and operate it for a limited period (similar to the “golden share” component), after which it returned to the public administration. For example, in constructing an urban metro system, the company that wins the tender builds the system, operates it for about twenty years, and then returns it to the government. Indeed, most of the reforms currently underway include removing the monopoly of a government company and moving to privatization by means of tenders for concessions and establishment of metropolitan transportation administrations (Citroën, 2017; Drew & Ludewig, 2011; Thomas & Bertolini, 2020).

Measuring the Success of Reforms

Since transportation in Israel suffers from government and market failures, an attempt was made to locate markets and countries that demonstrated success factors. Two studies were chosen with a number of elements that contributed to the success of changes and reforms in countries with features similar to Israel. The first was the study by Pollitt & Bouckaert that looks at changes in public administration in Western countries. The authors focus on the political system, the impact of socioeconomic forces, the administrative system, and the decision making process. In their research analysis, they emphasize the elements that led to successful reforms (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004).

In the second study, by Jeremy Drew and Johannes Ludewig, the emphasis is on reforms in transportation. They look at countries over a period of twenty years and create a professional database that indicates reforms in the field of urban public transportation, cargo trains, and intercity passenger trains (Drew & Ludewig, 2011).

Analysis of data from these two studies reveals an overlap in elements that contributed to improvements in public transportation and administration. Both reflect the impact of globalization and neo-liberalism as accelerators of reform. Analysis of the reforms highlights the link between reforms in public administration and success in the field of transportation. The common factors in the success of reforms are reduced bureaucracy, decentralized powers, privatization, review, and performance assessment. The studies describe successes in several countries; three countries will serve as representative examples (Table 1).

England—crisis in the 1970s, high inflation: From 1979 to 1990 the Thatcher government introduced a long series of reforms and significant institutional changes in public administration. The 2008 crisis struck England again and led to a whole range of reforms in the public sector, particularly the civil service, management, and the reduction of bureaucracy. All government offices underwent changes, mainly decentralization and the expansion of review systems, and the result was considerable improvement to operations (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004, pp. 313-321).

Public transportation in England has been rejuvenated in the last thirty years. A decade of reforms created a situation in which by 2003 the rail infrastructure had doubled in size, the number of passengers increased by 80 percent, and there was a rise in the number of people employed by the transportation industry. The principal reforms included broad privatization and delegation of powers from a national administration to local city administrations. The result was a considerable reduction in government costs and growth in state revenues from the export of transportation goods. Regulation also underwent changes, from a situation where the public administration was the only regulator, to a gradual move toward private regulation and decentralization of powers (Drew & Ludewig, 2011, pp. 89-99).

Italy is generally ranked low on all aspects of government efficiency, with a high level of instability and lack of governance. The civil service has four layers: state, region, province, and municipality. Nevertheless, from the early 2000s numerous national reforms have been introduced that have changed the face of public administration: reduction of costs, less political involvement in public administration, reliable management skills, innovative tools for manpower management, and performance review (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004, pp. 285-290). The reforms in transportation have changed the Italian railway, which was a monopoly. Reducing bureaucracy saw the number of employees fall from 220,000 to 87,000, and privatization processes occurred. Improved efficiency can be seen in the laying of a thousand kilometers of new tracks, operation of advanced fast trains, new mass transit systems in large cities, less use of private vehicles, and the move to efficient public transportation (Drew & Ludewig, 2011, pp. 103-110).

Sweden is a modern, egalitarian country with an open economy, although it accumulated a budget deficit that caused an economic crisis at the end of the 1990s. At that time, new ideas about management reached Sweden, and the political system was open to implementing several reforms. Decentralization of powers to the regions and municipalities contributed to the modernization of budgeting systems, performance review and assessment systems were set up, and the National Audit Office was established as an important element of public administration. The direct results were reductions in bureaucracy and government expenditure (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004, pp. 305-312).

Until 1988 the railway was run as a government monopoly. Global influences led to changes in approaches and transportation policy, manifested by decentralization and the move to metropolitan transportation administration. Privatization opened the market to competition, leading to a huge increase in public transportation infrastructures, growth of 70 percent in passengers, and increased employment in the transportation industry, while municipal administrations developed mass transit systems for the large cities (Drew & Ludewig, 2011, pp. 115-124).

| Pollitt & Bouckaert: success factors in public administration | Privatization | Decentralization | Reduction of bureaucracy | Performance assessment | Drew & Ludewig on rail transportation– features of success |

| Tenders for concessions | Municipal administrations | One umbrella administration per project | Private professional regulation | ||

| England | Widespread | Transfer of powers | Comprehensive government mechanism | Reinforcing review with private regulation | Significant increase in revenues, growth in passenger numbers, better service |

| Italy | Somewhat successful | Transfer of powers to regions | To some extent | Powers for government review | Comprehensive development of infrastructures, greater use, expansion of metro and mass transit, fast trains |

| Sweden | Done | Partial, now extended | Greater efficiency | National Review Office | Expansion of infrastructures, developed urban transportation, increased passenger numbers |

Table 1. Transportation reforms, comparative review

Public Transportation in Israel

Historical Overview

In the four decades following the establishment of the State of Israel, the issue of public transportation made little progress. Two bus company monopolies, Egged and Dan, were formed, while in rail transportation, the country made use of the infrastructure and equipment left behind by the British. The state lost control over subsidy payments to the bus monopolies, which operated with no proper oversight and regular price rises, although the service was lacking. Railroad service was limited and was used mainly for tourism purposes by young people rather than as public transportation (Braidburg, 2002; Daskal, 2023). Analysis by political science and public administration researchers found that Israel’s deficient infrastructures were a function of the state budget’s overwhelming allocations to existential and security problems (Dror, 1992).

There is no dispute that the “stabilization plan” passed by the unity government in 1985 was highly successful in handling the economic crisis. It became the basis for extensive reforms in the economy and government ministries and corporation authorities, and enabled the transition to a free market economy (Ben-Bassat, 2001; Shefer, 2004; Maman & Rosenhek, 2007). Implementation of the stabilization plan created conditions that facilitated freeing transportation issues from many years of stagnation. Although global processes such as population growth, urbanization, globalization, and increasing use of private vehicles had not bypassed Israel, it was only in 1992 with the Rabin government that a process of transportation reform began, marked by a sharp change of approach. The first phase began when the Prime Minister identified the Histadrut labor federation as the interest group that was obstructing transportation development—in the eyes of the Histadrut, transportation reforms would harm the cooperatives, so it was in their interest to maintain the status quo and avoid competition. For its part, the railroad workers’ union wanted to retain its power and therefore, with Histadrut support, preferred not to change the existing framework.

Rabin understood that implementing reforms required the removal of barriers, and he began dismantling some centers of Histadrut power (Gabbai, 2019). He appointed Histadrut Secretary Israel Keisar as his Minister of Transportation, which removed the main pressure group of the time, and thus opened the way to implementing different policies. Reforms that shaped new public policy in transportation were also adopted by subsequent governments. From the start, the direction was clear and in line with the measures that were successfully implemented in other countries. Among these:

- Privatization: The government passed resolutions to open the bus market to other companies (Prime Minister’s Office, 1997). Later resolutions dealt with the involvement of the private sector in developing mass transit systems in urban blocs (Prime Minister’s Office, 2002).

- Decentralization: It was decided to set up metropolitan transportation administrations (Prime Minister’s Office, 3988).

- Reduced bureaucracy: Resolutions were passed to set up NTA (Metropolitan Mass Transfer System Ltd.) as the umbrella company responsible for mass transit in the central region and remove the Tel Aviv metropolitan administration. Similar resolutions were passed in Haifa and Jerusalem.

- Performance review and regulation: In this context nothing changed, and remains in the hands of the professionals in public administration.

As reforms developed, Ministry of Transportation budgets began to grow; the public also showed great interest in this public good and voted with their feet. The improvements in bus service led to increased usage; new infrastructures and modern railroad cars caused passenger journeys to rise from a few million to over 70 million journeys annually; and the light rail began to operate in Jerusalem. But with all this, there is still a wide gap between the correct decisions made by various governments and the actual processes of shaping and implementing policy.

Current State of Public Transportation

in 2023, some thirty years after reforms began, there is no mass transit system in any of the large urban blocs. Companies report a shortage of 5,000 bus drivers (Zagrizek, 2022). Most intercity rail journeys are overcrowded, there is a shortage of railroad cars, and the infrastructure does not reach the outer periphery (Amsterdamsky, 2023). Figure 5 reflects the situation of public transportation in Israel.

Figure 5. Use of private vehicles compared to public transportation | Source: CBS

These figures suggest that most citizens are dissatisfied with the quality of the product provided by the government, very far from the DTD model. They found a substitute, and gradually through alternative politics[2] chose private vehicles instead of inconvenient and inefficient public transportation. The use of private vehicles is also encouraged by benefits that interest groups offer companies and individuals (such as leasing, easy loans). Moreover, when the government bans public transportation on the Sabbath, families feel compelled to buy cars in order to meet friends and family on the weekend. The public is apathetic about the problems of public transportation, and there are no protests on the subject.

A factor that reflects public attitudes and is recognized as a widespread and important influence in a democratic society is the third sector. As of 2012, the number of third sector organizations registered with the Registrar of Associations in Israel amounted to 49,916 (Cohen & Mizrachi, 2017, p. 147), of which the number of associations working for more efficient public transportation is still in single digits, and their impact is therefore very slight.

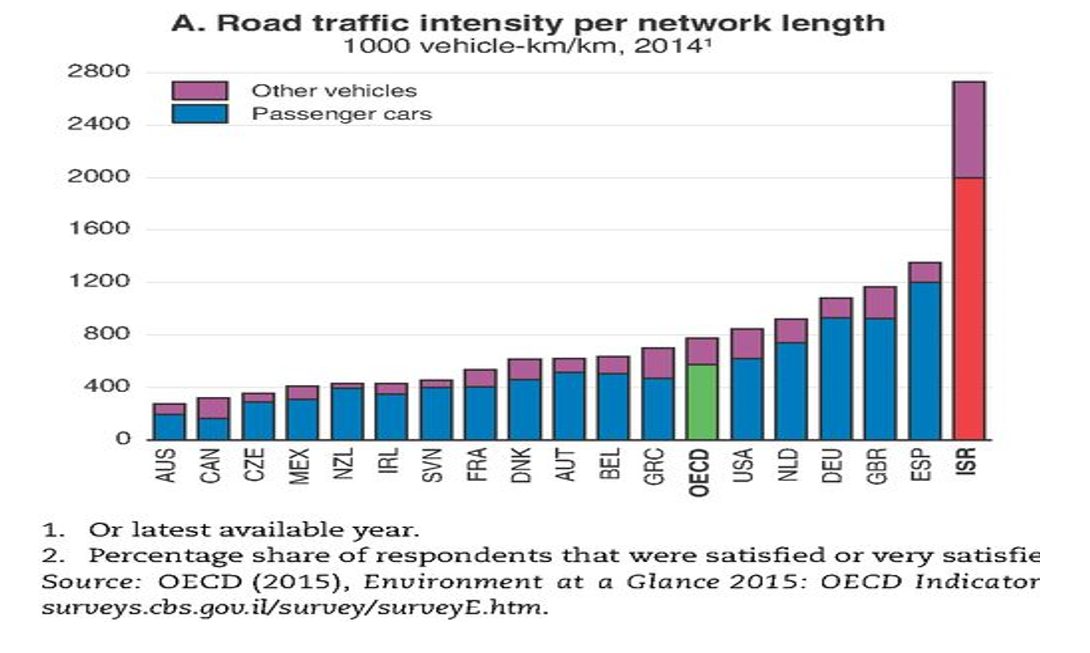

Another result of the huge increase in private vehicles is expressed in a report published by the OECD in 2015 dealing with congestion on the roads in OECD countries. The key was the number of kilometers of road per 1000 vehicles. Figure 6 shows that Israel’s roads are three times more congested than the OECD average.

Figure 6. Congestion on Israel’s roads | Source: Ministry of Transportation and Ministry of Finance data, 2020

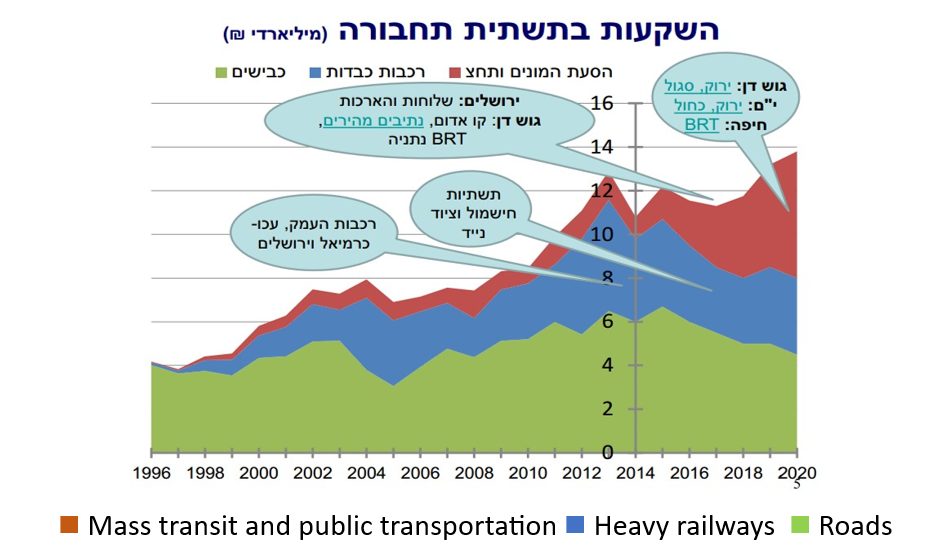

Since this survey was conducted in 2015, the situation has deteriorated, as every year the Israeli public purchases some 300,000 new cars, while the speed of developing new infrastructures cannot provide a proper response to this rate of increase (Aviram, 2017). The lack of infrastructure and congestion on the roads are the main causes of loss of life in road accidents and of air pollution. However, If the country was serious about dealing with this congestion, it would encourage the use of public transportation and allocate suitable budgets. Yet as Figure 7 indicates, over the years, greater budgets have been allocated to build roads than those allocated to public transportation.

Figure 7. Investments in transportation infrastructures (NIS billions) | Source: Ministry of Transportation and Ministry of Finance data, 2020.

In other words, the preference has been to build roads, which are used mainly by private vehicles, while public transportation is of secondary priority. Until 2018, the budget for public transportation was NIS 5 billion and NIS 6 billion for road development. It was only in 2020 that public transportation received a higher budget than roads. This means that over the years, government budgets have provided significant resources for the benefit of private vehicles.

In an attempt to understand the gap between normative, professional, and correct decisions and the failures revealed by the empirical data, Daniel Maman and Zeev Rosenhek contend that global influences on Israeli actors such as reports from the World Bank, the IMF, and the OECD force decision makers to make reforms to bring Israel into line with other properly run countries (Maman & Rosenhek, 2008). Once decisions are made, however, regulatory capture, or if we expand the scope according to the theory of public choice, the personal interests of politicians and bureaucrats, lead to a policy of retaining the status quo and do not promote public interests.

Interest groups worked hard to reach the status quo. The development of efficient and convenient public transportation affects the import of private vehicles, insurance companies, taxi owners, and leasing companies. The groups therefore provided benefits for politicians and employed numerous bureaucrats who left public service and obtained senior positions in companies forming interest groups (Zelekha, 2008).

In 2019 state revenues from taxes on private vehicles, license fees, excise duty on fuel, and usage equivalency amounted to NIS 41 billion (Ministry of Finance, 2019). This figure puts the Ministry of Finance at the head of the interest groups opposed to elements that could limit this income, while the Budgets Division also encouraged the continuation of the status quo and did not rush to implement the reforms. The call at the central committee of the Likud and the announcement “we want jobs” reflected the socio-political culture that was part of the considerations of senior officials in the party (Vardi, 2002). Over the years ministers of transportation have found the Ministry a convenient launching pad for political appointments.

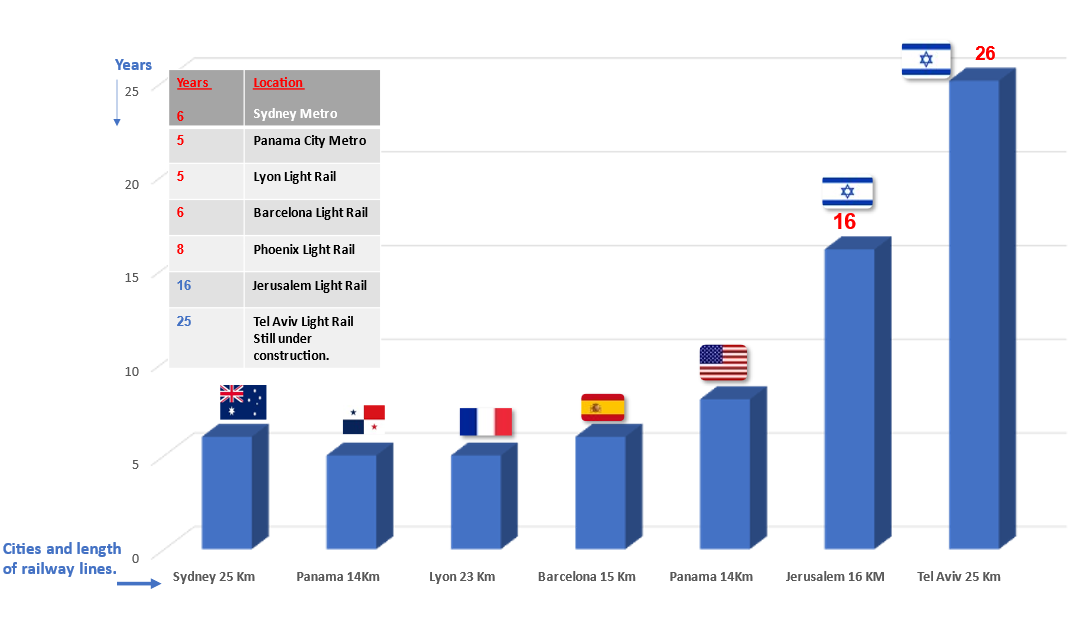

The assessment that it is possible to be appointed to an important position in the management of a national project without suitable training led to a substantial waste of public money. The lack of professionalism was reflected in the delays in completing important reforms in transportation, as shown by Figure 8.

Figure 8. International mass transit systems | Source: Data reported in the press and from www.railwaygazette.com

One of the measures of success included in government decisions is the improvement in performance reviews. The most striking example of a lack of proper review is the Red Line of the Tel Aviv Light Rail. The tender was issued in 2001 and four large professional international companies submitted bids that included a schedule for completion of the work within five years, for a government budget of NIS 7 billion. Today, 28 years after the establishment of NTA, government costs up to the operation of the line in August 2023 total some NIS 20 billion (Daskal, 2022). In Jerusalem, although the Light Rail began to operate successfully in 2011, it was only after a tender concluded in 2021 that a company was selected to construct an additional line (Master Plan Team for Jerusalem Transportation, n.d.).

There is no doubt that these examples validate the claim that over the past decades interest groups are the winners, and the status quo serves them rather than the wider public. Bus services in Israel are regulated by the government. The Ministry of Transportation preferred to settle subsidies with a limited number of bus companies, and thus Egged and Dan emerged as monopolies. The government tried to deal with the problem in the absence of detailed information about passenger numbers, real costs, and demand. This weakened the government’s bargaining power and in fact, it lost the ability to restrain rising costs. Lack of competition meant a considerable decline in standards. The market was only opened in 1997 when other bus companies were given licenses to operate in specific areas (Braidberg, 2002).

Even after so many years, Egged and Dan are still the largest companies in the privatized market, and the government has no control over subsidies. If Egged, which lacks over 1,000 drivers, can distribute a dividend of NIS 500 million in 2023 (Hazani, 2023), the clear conclusion is that there is no public administrative control of the subsidies that were intended to meet the basic needs of the general public.

Both the sociological approach, based on the new institutionalism theory, and Pollitt & Bouckaert stress that political culture has a significant influence on decision makers. In Israel, this influence is prominent and is reflected in decisions on public transportation.

The influence of the political culture in Israel is usually most obvious after the formation of a new government. In nearly all cases, when a minister is appointed, his/her first step is to appoint senior staff, which are often political appointments. Later, in public statements, some of the reforms that were advanced—often reforms initiated by ministers belonging to the same party—are canceled. This was recently done by the Minister of Education (Ilan, 2023). A similar process occurred with the current Minister of Transportation and the metro plans.

Transportation infrastructure projects usually last several years. Since the establishment of the state there have been 32 ministers of transportation, in other words, the average term in office is less than two years, while 12 ministers served for less than a year. Nevertheless, many ministers, with a lack of professionalism and based on personal interests, have canceled or rejected reforms introduced by their predecessors. This lack of governance has created a “pendulum of reforms.” Table 2 gives examples of just a few of the events created by ministers over the years.

| Event | First decision on change/ reform | Cancellation of the first decision | Revival of the first change decision |

| NTA – first light rail line – Red Line | 2001 – establish NTA, tender for concession | 2010 – winner nationalized, project transferred to NTA, government company | 2019 – return to new tender for the following lines |

| Electrification of the railway | 2005 – tender for work | 2007 – tender canceled | 2015 – new electrification tender |

| Tel Aviv-Jerusalem rail line | 1998 – closure of old line, plan for new line | 2001 – old line was renovated and reopened | 2006 – work starts on the new line (Line A1) |

| Haifa mass transit system | 2001 – light rail plan | 2011 – tender for mass capacity buses | 2019 – light rail tender, new Haifa-Nazareth line |

| Jerusalem light rail – Red Line | 2001 – tender for 27-year operating concession | 2018 – the state buys back the concession | 2020 – concession is given to a new winning company |

| 1973 – Government decision on Tel Aviv metro 1996 – feasibility study for the metro | Budget constraints – light rail instead of metro | Continued construction of light rail | 2018 – return to the metro option in Greater Tel Aviv; decision not yet final |

Table 2. The “pendulum of reforms” effect on transportation in Israel | Source: Websites of the Ministry of Transportation, NTA, Israel Railways, Yeffe Nof, Transportation Master Plan

Not one of these examples shows any professional or budgetary reason for changing or canceling the reform that was outlined from the start by the professional echelon. Clearly, these processes extend the duration of implementation, increase costs, and are a direct cause of government failure. Academic definitions of government failure also point to a lack of governance, over-centralization, and short-term planning. In fact, as an economic term that is also used in the analysis of public policy, it refers to the failure to achieve efficiency in a public good that the population needs (Weimer & Vining, 2011; Hirschman, 1982).

Transportation and Links to National Security

Based on the experience of other countries, more efficient design of public transportation in Israel could help provide a response to two foreseeable problems in the field of national security:

- Protection of the civilian front: Due to rocket and missile attacks on Israel and intelligence about future nonconventional attacks, protection of the civilian front is a vital part of the security system. In an article on national resilience (2012), Maj. Gen. (res.) Eyal Eisenberg, former head of the Home Front Command, wrote that a third of the Israeli population lacks standard protection, particularly in the large urban areas. Metro stations in urban blocs could reduce this gap, as is the case in many cities worldwide. The first government resolution on constructing a metro system in Israel was passed in April 1973. The current Minister of Transportation is still delaying the Metro Act (Cohen, 2023).

- Troop movements by rail: In summarizing Operation Guardian of the Walls in Gaza (May 2021), which was accompanied by violent incidents in cities within Israel with mixed Jewish and Arab populations, security figures expressed concern over two logistical matters. One is the lack of drivers for tank carriers and buses to transport troops, when drivers from the Arab sector fail to report for their work in transportation companies. The second is the difficulty of driving along certain routes (e.g., Wadi Ara) because of demonstrations. This was extensively covered by the media (Yehoshua, 2021).

Rail transportation is a central building block of military logistics worldwide, as with the United States Army. If Israel had a more developed railroad infrastructure, the lessons of Guardian of the Walls would not have included logistical problems. One steam engine driver can take a whole armored battalion with all components, without the need for dozens of armored truck drivers and without causing traffic jams, which would overcome the problem of blocked roads. It is easier to supervise railroad tracks than roads, so it would be easier to locate attempts to damage the infrastructure.

Thus, public transportation infrastructures can help to save lives, improve the economy and social welfare, close social gaps, and contribute to Israel’s security in general. Israeli public transportation is in dire need of improvements in order to cancel out market and government failures, caused by the harmful influences of the political culture and regulatory capture, in which interest groups play a not insignificant part. Significantly, there are countries that have succeeded in shaping and implementing changes and reforms, even the DTD model, using metrices that helped achieve success in wide-reaching reforms of public transportation. However, the question that remains is whether decision makers and politicians in Israel in previous decades chose to act contrary to the public interest with respect to the infrastructure for public transportation, and thus created a “march of folly” that in turn affects critical components of national security.

The March of Folly in Israeli Public Transportation

In her book The March of Folly (1986), Barbara Tuchman examined a long list of historical events and defined three conditions that turn policy into folly:

- The negative results of a decision must be clearly visible in real time and not in retrospect.

- There must be an alternative course of action that could have been adopted.

- The policy is the policy of a group, not a sole ruler.

It is possible to test these parameters against public transportation in Israel. Regarding the first condition: Since the decisions regarding reforms in public transportation were taken, the Knesset has received 15 reports from the State Comptroller and dozens of reports from experts, while the Knesset has issued 12 reports in preparation for debates on transportation. In all these documents the emphasis is on the urgent need for efficient public transportation, the growing damage caused by private vehicles, and the benefits of public transportation.

Regarding the second condition, a potential alternative course of action: In every proposal for reform there was an alternative, which still exists. The average annual loss of life on the roads is known to the decision makers. While the balance in Israel has hardly changed, European countries have found alternatives and successfully reduced road accidents. A European target was set for 2023 to reduce the number of dead and injured by 50 percent. The Or Yarok (Green Light) organization found that Israel was in 29th place among 32 countries for the reduction of road accidents from 2001-2020 (Or Yarok, 2021).

The government transferred responsibility for fighting road accidents to the National Road Safety Authority. In 2005 the Authority’s budget was NIS 550 million, and in 2021, NIS 73 million. Assaf Zagrizek wrote: “The slaughter on the roads never stops, but the state is drying up the National Road Safety Authority” (Zagrizek, 2021). In addition, although the rapid increase in the number of private vehicles bears the lion’s share of responsibility, in 2010 then- Minister of Transportation Israel Katz referred proudly to the establishment of a committee to reduce the cost of purchasing new cars; its recommendations were accepted by the Knesset and came into force. This is contrary to global trends and the views of experts, who stress that policy should work in the direction of reducing private vehicle use (Huberman, 2010). Transportation Minister Miri Regev has issued a populist declaration that limits public transportation lanes and allows private vehicles to use them (Sadeh, 2023).

However, there are other alternatives, among them:

- Delegation of powers: Apart from the basic aim of increasing the number of companies and employees in professional offices, Israeli politicians and bureaucrats have been engaged in maintaining their centralized powers and opposing decentralization. However, decentralization is an alternative way to success. Dozens of countries that have set up municipal transportation administrations have experienced significant improvements in efficiency and quality. Decentralization is a principal component in the success of institutional changes and reforms in other countries. The government and the Knesset are aware of this, as shown in the special report prepared on this subject for discussion in committees, ending with a clear recommendation for municipal administrations (Ronen, 2009). In view of this and some media pressure, a government resolution was passed (Prime Minister’s Office, 2011) to set up municipal transportation administrations.For politicians, decentralization means granting some political autonomy to the cities, which in their assessment weakens their senior position, and they have therefore completely ignored government resolutions and State Comptroller reports. This was highly noticeable with then-Minister Katz, who saw NTA as a political asset, and during his ten years in office maintained centralization, ignored government resolutions and harsh reports from the State Comptroller, and stopped the establishment of transportation administrations in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem (State Comptroller, 2019). Even now there are no municipal transportation administrations in Israel. The negative outcomes are highly evident, yet there is clearly an alternative.

- Performance review and measurement: The story of the Tel Aviv Light Rail’s Red Line reflects how politicians relate to regulation and performance review. In brief, according to the NTA website, the decision to establish the NTA was passed in 1996, in order to conduct a survey for setting up a mass transit system in the country’s center. In 1998 a partial budget of NIS 2 billion was approved, instead of the planned budget of NIS 7 billion. In 2001 a tender was issued, but the winner was only decided in 2007. In 2008, during the global financial crisis, the winner met with financial difficulties. The alternative way all over the world was to recognize the crisis as force majeure, thus making it easier to bridge the gaps. In Israel, the tender winner was nationalized and the concession was transferred to NTA, a government corporation. So instead of commercial operation of the line starting in 2012, it only began operations in August 2023. Meanwhile, the original budget of NIS 7 billion is now close to NIS 20 billion (Daskal, 2022).

Public sector performance measurement has existed since the start of modern public administration. It is intended to increase the responsibility and transparency of government actions, and elected politicians and professional grade managers can realize the “symbolic benefits” of creating the impression of a well-functioning government (Moynihan, 2008). The former director of the Companies Authority Ori Yogev describes in his book his review of the financial conduct of government companies and wrote: “NTA was one of the worst companies we managed, with conduct that reflected the emotional nature of the actions of his chairman and chief executives. They made threats, spread slander, and did everything to avoid reviews, mainly through the use of the media and failing to cooperate…Their conduct was backed by the Minister of Transportation, and all attempts to suggest a change or practical alternatives for improvements and proper budget management were met with personal attacks on the critic” (Yogev, 2018, p. 180).

In spite of budget irregularities, no chief executive or board member of NTA was removed from his position on that account, and the board of directors was not dissolved due to management failure. Shlomo Mizrachi wrote that the approach to management, processes of defining policy, and assimilation between the two constitutes an interaction that leads to a policy of performance management—a concept that is bi-directional. On the one hand, there are ways in which policymakers can use performance to enrich management mechanisms. On the other hand, there are ways in which policy theories and methods can help to identify potential defects, and ways to plan and implement more effective performance management as a result (Mizrachi, 2017).

In the world of research and in business management practice, there are dozens of methods for planning and measuring performance. The data show that the public administration did not use any of the methods of review and regulation—not in Tel Aviv, not in Jerusalem, not in the bus sector. Thus, in spite of correct decisions for reforms and changes, politicians, bureaucrats, and interest groups managed to keep the status quo, and acted contrary to the national public interest in a way that also damages national security.

Regarding, the third condition, the issue of a group policy: In democratic Israel, changes, reforms, and policy design are done by ministers with the backing of government resolutions and the Knesset, so the basic condition for the march of folly are met.

The negative outcomes are familiar to decision makers, the available alternatives are known, and all this is happening in a democratic regime with the approval of the government and the Knesset. The public conduct shown by the handling of changes and reforms reflects an inefficient political culture, which mainly serves individual interests instead of the public interest. All this and more contribute to a moral distortion in Israeli society, leading to the conclusion that the current situation is the result of a march of folly in the field of public transportation in Israel.

Conclusion and Recommendations

A country’s transportation affects human lives, environmental quality, the economy, national infrastructures, society, and security. Therefore, the public transportation system has implications for elements of national strength (economic and technological strength, social resilience, population dispersal, industrial and technological centers of gravity, military logistics, protection, and more). Since national strength is the ultimate resource to ensure national security, transportation clearly has an impact on security in the widest sense. A government that has a security-political cabinet should also set up a transportation cabinet to deal with the market and government failures in this field, with thorough reference to the interfaces between transportation and national infrastructures, and the elements of national strength and their impact on national security.

If every meeting of the security cabinet included the subject of transportation, or separate meetings were arranged for the transportation cabinet, there would be an upgrade of the subject and the understanding of politicians, professional levels, the media, and the public, so that it would be possible to bring together the resources necessary to overcome the market and government failings that currently impair national resilience.

Transportation is a complex field and requires a multi-disciplinary approach. The government must make decisions based on evidence (evidence-based policy) and make use of international knowledge and experience, which is now highly available.

The media, the third sector, and the general public must change their approach and serve as a factor that influences decisions on transportation policy, as well as demanding that the political system consider the national public interest and pass laws that promote public transportation.

The decisions of transportation engineers and experienced professionals who rose through the ranks of public transportation administration have direct influence on lives. Therefore, if the security and health systems would not consider appointing a general or a hospital department manager as an external political appointment, so too there is a need for a mechanism or law or procedure whereby qualified transportation engineers must not be replaced by unqualified political appointees.

The gatekeepers and elected officials must adopt legitimate ways of reducing the negative effects of the political culture in Israel and work to change it, while restraining interest groups, stopping extensive political appointments, and preventing the pendulum of changes and reforms. They must address immediately the implementation of reforms that were already decided on the matter of buses and mass transit systems, and of the government decision on establishing municipal transportation administrations. They must also restore without delay the budget of the National Road Safety Authority. All this is essential to reinforce elements of Israel’s national strength in order to improve its national security.

References

Amsterdamsky, S. (2023, June 15). Not exactly the economy’s engine. Calcalist. https://tinyurl.com/32y27r6b [in Hebrew].

Aviram, H. (2017). Transportation economy. Ofir Bikkurim [in Hebrew].

Baldwin, R., Cave, M., & Lodge, M. (2012). Understanding regulation: Theory, strategy, and practice. Oxford University Press.

Evans, E.J. (2013). Thatcher and Thatcherism. Taylor & Francis Group.

Ben-Bassat, A. (2001). The way of obstacles to a market economy in Israel. In A. Ben-Bassat (Ed.), From government involvement to a market economy: The Israeli economy 1985-1988, collected articles in memory of Prof. Michael Bruno (pp. 1-48). Am Oved [in Hebrew].

Ben-David, D. (2003). Israel’s transportation infrastructure from a socio-economic perspective. Economic Quarterly, 50(1), 91-104. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23776166 [in Hebrew].

Braidberg, A. (2002). Reforms in public transportation (Doctoral dissertation). Technion.

Campbell, J. L. (2004). Institutional change and globalization. Princeton University Press.

Carmon, N., & Fainstein, S. S. (Eds.). (2013). Policy, planning, and people: Promoting justice in urban development. University of Pennsylvania Press .

Carpenter, D., & Moss, D. (Eds.). (2014). Preventing regulatory capture: Special interest influence and how to limit it. Cambridge University Press.

Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). (n.d.). Transportation. https://tinyurl.com/yp5nmdfh [in Hebrew].

Citroën, P. (Ed.). (2017). UNIFE: World rail market study forecast 2012 to 2017. Eurail Press.

Cohen, A. (2023, June 5). Regev is blocking the Metro, but the residential district has already been promoted in its operating complex. TheMarker. https://tinyurl.com/yyycn5ja [in Hebrew].

Cohen, N., & Mizrachi, S. (2017). Introduction to public administration and management. Open University [in Hebrew].

Daskal, Y. (2022, October 9). Delay, waste, and inefficiency: Will the lessons of the Red Line be learned? Ynet. https://tinyurl.com/2nejdzss [in Hebrew].

Daskal, Y. (2023). Designing a policy for rail transportation in Israel. Regulatory Studies, Volume G, 255-284. Rina & Meir Heth Center for Competition and Regulation Studies, College of Administration. https://tinyurl.com/4pvnak3f [in Hebrew].

Drew, J., & Ludewig, J. (Eds.). (2011). Reforming railways: Learning from experience. Eurailpress.

Dror, Y. (1992). Memorandum to the Prime Minister: A state of the nation. Y. L. Magnes Publishers [in Hebrew].

Eisenberg, E. (2012). Principles and challenges for building national resilience. In M. Elran & A. Altshuler (Eds.), The complex mosaic of the civilian front in Israel (pp. 81-88). Memorandum 120. Institute for National Security Studies. https://tinyurl.com/yf8x863u [in Hebrew].

Feitelson, E. I. (2011). Issue generating assessment: Bridging the gap between evaluation theory and practice? Planning Theory & Practice, 12(4), 549-568. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2011.626305

Finck, M., Lamping, M., Moscon, V., & Richter, H. (Eds). (2020). Smart urban mobility: Law, regulation, and policy. Springer

Friedman, T. L. (2005). The World is Flat. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Gabbai, Y. (2019). Society of abundance without welfare and without peace: Netanyahu versus the Rabin legacy. Carmel[in Hebrew].

Guillén, M. F. (2003). The limits of convergence: Globalization and organizational change. Princeton University Press.

Hacker, J. S. (2004). Privatizing risk without privatizing the welfare state: The hidden politics of social policy retrenchment in United States. American Political Science Review, 98(2), 243-260. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055404001121

Hall, P. A., & Taylor, R. C. R. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), 936-957. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

Harkabi, Y. (1990). War and strategy. Maarachot [in Hebrew].

(2013). Not for turning: The life of Margaret Thatcher. Bantam.

Hazan, R. Y. (1999). Yes, institutions matter: The impact of institutional reform on parliamentary members and leaders in Israel. Journal of Legislative Studies, 5(3-4), 303-326. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572339908420606

Hazani, G. (2023, June 4). Seven months after the acquisition: Kiston withdraws 70% of Egged equity as a dividend. Calcalist. https://tinyurl.com/mrdr5pcz [in Hebrew].

Hirschman, A. O. (1982). Shifting involvements: Private interest and public action. Princeton University Press.

Huberman, O. (2010, February 18). Executive summary: Fast work interview with Transportation Minister Israel Katz. Calcalist. https://tinyurl.com/3865asv5 [in Hebrew].

Ilan, S. (2023, January 5). Kisch cancels the matriculation reform of Shasha Biton and formulates his own plan. Calcalist. https://tinyurl.com/54hb7523 [in Hebrew].

. (2009). Innocent abroad: An intimate account of American peace diplomacy in the Middle East. Simon & Schuster.

Larkin, E. J., & Larkin, J. G. (1988). The railway workshops of Britain, 1823-1986. Macmillan.

Leach, J. (2004). A course in public economics. Cambridge University Press, p. 5.

Levi-Faur, D., & Vigoda-Gadot, E. (Eds.). (2004). International public policy and management: Policy learning beyond regional cultural and political boundaries. Taylor and Francis.

Magbanua. J. (2021, March 25). No train, no gain: U.S. Army keeps the freight moving. Army Reserve. https://tinyurl.com/ybcbyw6s

Maman, D., & Rosenhek, Z. (2007). The politics of institutional reform: The “declaration of independence” of the Israeli central bank. Review of International Political Economy, 14(2), 251-275. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25261910

Maman, D., & Rosenhek, Z. (2008). Making the global present: The Bank of Israel and the politics of inevitability of neo-liberalism. Israeli Sociology, 10(1), 107-131. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23442632 [in Hebrew].

Maoz, Y. (2021). Introduction to microeconomics. Open University [in Hebrew].

March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1984). The new institutionalism: Organizational factors in political life. American Political Science Review 78(3), 734–749. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961840

Master Plan Team for Jerusalem Transportation. (n.d.). Jerusalem on the way to a new reality. https://jet.gov.il/ [in Hebrew].

Ministry of Finance (2022, March 8). Report on state revenues for 2019-2020. https://tinyurl.com/bdcs4vcm [in Hebrew].

Mitchell, W., & Munger, M. C. (1991). Economic models of interest groups: An introductory survey. American Journal of Political Science, 35, 512-546.

Mizrahi, S. (2017). Public policy and performance management in democratic systems: Theory and practice. Springer International Publishing.

Mizrachi, S., & Midani, A. (2006). Public policy between company and law: The Supreme Court, political participation, and shaping policy. Carmel [in Hebrew].

Moynihan, D. P. (2008). The dynamics of performance management: Constructing information and reform. Georgetown University Press.

Navot, D. (2012). Political corruption in Israel. Israel Democracy Institute. https://tinyurl.com/2p9cfvke [in Hebrew].

Navot, D., & Cohen, N. (2015). How policy entrepreneurs reduce corruption in Israel. Governance, 28(1), 61-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12074

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

Oatley, T. (218). International political economy. 6th ed. Routledge.

Or Yarok. (2021). Report on road safety: Israel compared to Europe. https://tinyurl.com/5n6nshky [in Hebrew].

Ovenden, M. (2003). Metro maps of the world. Singapore: Capital Transportation publishing CS Graphics.

Pierson, P. (1996). The new politics of the welfare State. World Politics, 48(2), 117-143. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25053959

Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2004). Public management reform: A comparative analysis (2nd edition). Oxford University Press.

Prime Minister’s Office. (1997). Overall policy for dealing with the problem of congestion on the roads and preference for public transportation. Government Resolution no. 2457 of 13.08.1997. https://tinyurl.com/ycxh2uuv [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office. (2002). Integrating the private sector in the execution and management of transportation projects: State Comptroller’s Report no. 52b. Government Resolution no. 1819 of 16.05.2002. https://tinyurl.com/yyrh2y7n [in Hebrew].

Prime Minister’s Office. (2011). Establishment of a national authority for public transportation and metropolitan transportation authorities. Government Resolution no. 3988 of 18.12.2011. https://tinyurl.com/k7d7kex5 [in Hebrew].

Ram, A. (2006). Globalization. In A. Ram & N. Berkowitz (Eds.), In/equality (pp. 90-99). Ben Gurion University of the Negev [in Hebrew].

Rina & Meir Heth Center for Competition and Regulation Studies (2019). Methodology for examining concentration in the general economy. In Legal Review June 2019 (pp. 7-8), College of Administration. https://tinyurl.com/57bxncxu [in Hebrew].

Rolnik, G., & Shapira, R. (2018). The dynamics of regulatory capture: Study of the Israeli case. Shmuel Ne’eman Institute [in Hebrew].

Ronen, Y. (2009, August 9). Metropolitan transportation authorities worldwide and in Israel. Knesset Research & Information Center. https://tinyurl.com/yemzhxer [in Hebrew].

Sadeh, Y. (2023, January 10). Miri Regev effectively cancels enforcement on the plus lane of the Coastal Highway. Calcalist. http://tinyurl.com/4ndcaskk [in Hebrew].

Shalev, M. (2004). Have globalization and liberalization “normalized” the political economy in Israel? In D. Flick & A. Ram (Eds.), The rule of capital: Israeli society in the global era (pp. 84-115). Hakibbutz Hameuhad and Van Leer Institute in Jerusalem. [in Hebrew].

Sheffer, G. (2004). Global and local processes and the weakening of Israel’s political institutions. In. M. Naor (Ed.). State and community (pp. 9-13). Y. L. Magnes [in Hebrew].

Spiker, P. (2022). How to fix the welfare state: Some ideas for better social services. Bristol University Policy Press, pp. 121-130.

State Comptroller. (2019). The public transportation crisis. Special Audit Report. https://tinyurl.com/4nbaemsm [in Hebrew].

Streeck, W., & Thelen, K. (2005) Beyond continuity: Institutional change in advanced political economies. Oxford University Press.

Thomas, R., & Bertolini, L. (2020). Transit-oriented development: Learning from international case studies. Springer International Publishing.

Trajtenberg, M., Cohen, S., Pardo, A., & Sharav, N. (2018). Releasing the Gordian Knot: Transportation outline for the short term. Shmuel Ne’eman Institute, Technion. [in Hebrew].

Tuchman, B. (1984). The march of folly: From Troy to Vietnam. Knopf.

Vardi, R. (2002, October 10). Want jobs? Y-e-e-s! God now likes Likud members and even more, those who were elected to the party committee. Globes. https://tinyurl.com/3w5cnv7j [in Hebrew].

Weimer, D. L. (2005). The potential of contingent valuation for public administration practice and research. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(1-2), 73-87. DOI:10.1081/PAD-200044564

Weimer, D. L., & Vining, A. R. (2011). Policy Analysis: Concepts and practice. Longman.

Yadin, S. (2020). Interpretation of the regulatory contract: Following the Zeligman rule. In Nevo Theoretical Forum in Law, 44 (pp. 3-14). Tel Aviv University [in Hebrew].

Yehoshua, Y. (2021, July 16). The Arab drivers didn’t come: Figures that worry the IDF. Ynet. https://tinyurl.com/yc854h4x [in Hebrew].

Yogev, O. (2018). Without outside considerations. Yediot Books [in Hebrew].

Zagrizek, A. (2021, July 9). The slaughter on the roads never stops, but the state is drying up the National Road Safety Authority. Ynet. https://tinyurl.com/yyzmdx2t

Zagrizek, A. (2002, May 11). Why does nobody want to be a bus driver? It’s not only because of the pay. Globes. https://tinyurl.com/y7b2dx47 [in Hebrew].

Zelekha, Y. (2008). The black guard. Kinneret Zmora Beitan Dvir [in Hebrew].

Further Reading

Appendix 1. Government resolutions on the subject of transportation [in Hebrew]

- Resolution 2308 of 30.7.2002: Making Israel Railways a limited company. https://tinyurl.com/5ah29x82

- Resolution 2561 of 15.9.2004: Regulating the public transportation and railway industry. https://tinyurl.com/bdfymzkt

- Resolution 4329 of 26.10.2005: Authorizing NTA Ltd. to act on behalf of the state. https://tinyurl.com/muwv9957

- Resolution 1421 of 24.2.2010: Netivei Israel: Transportation plan to develop the Negev and Galilee, 5770-2010. https://tinyurl.com/2a2wzm3n

- Resolution 2569 of 12.12.2010: Usage of Tel Aviv Light Railway budgets. https://tinyurl.com/225fz6vj

- Resolution 3987 of 18.12.2011: Setting up mass transit systems. https://tinyurl.com/4k7mh4mv

- Resolution 1575 of 17.4.2014: Principles of the outline agreement between the Government and Israel Railways Ltd. https://tinyurl.com/4k7mh4mv

- Resolution 1838 of 11.8.2016: Multi-year investment program for the development of metropolitan public transportation. https://tinyurl.com/34fw72zr

- Resolution 1865 of 11.8.2016: Raising of bonds by Israel Railways Ltd. https://tinyurl.com/mrwetsud

- Resolution 3012 of 3.9.2017: Master plan for infrastructure development in Israel. https://tinyurl.com/835wn5sk

- Resolution 2558 of 24.3.2017: Transfer of Netivei Ayalon Ltd. to full state ownership. https://tinyurl.com/4eanz5cx

- Resolution 3426 of 11.1.2018: Setting up metropolitan transportation authorities. https://tinyurl.com/4zw2dueh

- Resolution 421 of 7.10.2020: Transfer of transportation projects from Yeffe Nof Ltd. to government corporations. https://tinyurl.com/3un53bna

Appendix 2: Websites used for this paper

UN research papers: https://www.un.org/en/our-work/documents

Bank of Israel Research Division: www.boi.org.il [in Hebrew]

World Bank reports: https://www.worldbank.org