Strategic Assessment

Relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors seem poised to embark on a path of mutual cooperation. This new reciprocity stands in marked contrast to the relations of Israel’s first decades, and reflects a transition from hostility, hatred, and rejection to coexistence and perhaps peace and cooperation, even if this change stems from the lack of other options. These new relations also reflect the changing face of the Middle East of recent years: the weakening of the Arab states, the decline of Arabism, and the rise of Israel to the point of its becoming a regional actor with significant military, political, and economic power. Although the Palestinian cause has lost its centrality as a defining issue in Arab-Israel relations, it continues as a glass ceiling that blocks efforts to promote relations between Israel and the Arab world. In addition, the relations Israel has formed with its Arab neighbors rest on regime and political interests, but lack widespread support among Arab public opinion.

Keywords: Arab-Israel relations, peace process, Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Arab world

Introduction

In December 1999, peace negotiations between Israel and Syria were restarted.

At a ceremony on the White House lawn, Syrian Foreign Minister Farouk a-Sharaa,

who was sent to Washington by Syrian President Hafez al-Assad to engage in the

peace talks with Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, declared that achieving

peace between the two countries would turn the "existential conflict"

between Israel and the Arabs, in which the two sides conducted a total war

aimed at destroying one another, into a "border dispute" that could

be settled at the negotiating table. A-Sharaa explained,

Those who refuse to return the occupied territories to their original owners in the framework of international legitimacy [the UN resolutions] send a message to the Arabs that the conflict between Israel and Arabs is a conflict of existence in which bloodshed can never stop, and not a conflict about borders, which can be ended as soon as parties get their rights…We are approaching the moment of truth…And there is no doubt that everyone realizes that a peace agreement between Syria and Israel and between Lebanon and Israel would indeed mean for our region the end of a history of wars and conflicts, and may well usher in a dialogue of civilization and an honorable competition in various domains the political, cultural, scientific and economy (a-Sharaa, 1999).

Later, at a conference of the Arab Writers Union in Damascus in

February 2000, a-Sharaa added that the Arabs should recognize that Zionism had

the upper hand in its historic struggle with the Arab national movement, a

struggle that began early in the 20th century with the emergence of

these two movements on history’s stage. He stated that achieving a peace

agreement with Israel was therefore a lesser evil for the purpose of ending

this struggle, which the Arabs could no longer win (a-Sharaa, 2000).

These remarks by a-Sharaa, and the fact that he was sent to the White

House to meet Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, showed willingness, and

perhaps even urgency, on the part of Damascus to reach a peace agreement with

Israel. The failure of the summit between Syrian President Hafez al-Assad and

United States President Bill Clinton in Geneva in March 2000, however, and the

Syrian President's death in June 2000 ended any chance of an agreement between

Israel and Syria. Several months later, in September 2000, the second intifada

broke out. This prompted the collapse of the negotiations that were underway

between Israel and the Palestinians, and doomed the two sides to continue a

bloody struggle that cost them thousands of victims (Rabinovich, 2004).

For a moment, it appeared as though the trend toward acceptance, and

even reconciliation, between Israel and the Arabs, which in the late 1990s

seemed to have progressed to a point of no return, had come to a halt. Two additional

indications of this were Hezbollah becoming a recognized and important actor in

Lebanon, following the IDF's unilateral withdrawal from the security zone in southern

Lebanon in May 2000, and the Hamas takeover in the Gaza Strip in a military

coup against the Palestinian Authority (PA) in February 2007, more than a year

after Israel unilaterally withdrew from the area in August-September 2005.

These two organizations reject the possibility of any acceptance of Israel or

reconciliation with it, and advocate maintaining an armed conflict. Their

achievements in Lebanon and the Gaza Strip therefore seemingly showed that despite

the statements by Foreign Minister a-Sharaa, there was no necessity or urgency

in reaching a settlement with Israel. On the contrary; it was possible to continue

fighting and score achievements in this armed conflict. Eventually, however,

Hezbollah and Hamas also had to reach understandings with Israel, even if

indirect. Moreover, Israel continued to advance relations with most of its Arab

neighbors, and even achieved cooperation with several of them, mostly of a

clandestine nature concerning security matters.

The story of Israel's relations with its Arab neighbors since its

founding in May 1948 is therefore one of evolution from hostility, enmity, and

rejection of acceptance, to readiness for coexistence and peace, albeit

sometimes for lack of choice, culminating even in a common desire for

cooperation, partly in strategic dimensions, given shared challenges and

threats.

All of this reflects the changes in the Middle East in recent decades:

the weakening of Arab states and the decline of pan-Arabism, while Israel grew

stronger and became a militarily, politically, and economically powerful

regional actor. This change in the Middle East narrowed the centrality of the

Palestinian question to the establishment of Arab-Israeli relations, as it was

no longer the axis around which those relations revolved. The issue is still

important, and continues to constitute a glass ceiling in any effort to promote

relations between the Arab world and Israel. As of now, however, Arab countries

have successfully maneuvered between their commitment to the Palestinian cause,

especially the commitment of Arab public opinion on this issue, and their

pressing political interest in preserving and advancing their relations with

Israel.

The Arab-Israeli conflict, and even the conflict between Israel and

the Palestinians, has been perceived for many years as a key issue for the

future of the Middle East, and of central importance to the stability of the

entire region, with consequences for stability in other parts of the world.

This accounts for the efforts that have been made by the international

community and are still underway to resolve the conflict. Over the years,

however, it has emerged that the conflict, or rather this amalgam of conflicts

between Israel and the Palestinians and Israel's other Arab neighbors, was only

one of a long series of conflicts and crises competing for a place on the

current regional and international agenda, and not necessarily the most

important. Other issues, such as religious fundamentalism, the spread of

Islamic terrorism, and the rise of radical Islamic jihad groups such as al-Qaeda

and the Islamic State, have taken the place of the Arab-Israeli conflict on the

public agenda. Furthermore, many Arab countries have experienced internal

crises, some of which have caused the collapse of the nation-state; the

appearance of non-state players, e.g., Hezbollah and Hamas; and the outbreak of

bloody civil wars. Also noteworthy is the competition for influence and

regional hegemony between two old-new regional powers, Turkey and Iran. Iran is

the more dynamic, intransigent, and daring of the two. The rise of Shiite Iran

and the tension between it and large parts of the mostly Sunni Arab world have

marked a divide that now extends throughout the entire length and breadth of

the Arab and Muslim world. Its success in consolidating its grip in large areas

of the Middle East has cast a threatening shadow over Israel, but also over

many of Israel's Arab neighbors.

The Middle East of today poses quite a few challenges to Israel, but

opens a window of opportunity to play a leading role in the region, and in any

case enables Israel to cultivate further its relations with the surrounding Arab

world. Israel's working assumption should be that Arab-Israeli coexistence and

cooperation can rest on firm ground, not on shifting sands.

Israel and

the Arab World: From War to Peacemaking

During the first decades of its existence, Israel's relations with the

Arab world surrounding it consisted of a bloody struggle between Jews and Arabs

over the Land of Israel. This conflict began during the late period of the

Ottoman Empire, when Jews began immigrating to the Land of Israel, and

escalated during the years of the British Mandate. The conflict reached a peak

in Israel's War of Independence in May 1948, which ended in a double defeat for

the Arab world: the defeat of the Arabs living in Palestine, many of whom became refugees in the

neighboring Arab countries, and the defeat of Arab countries that sent their

armies to take part in the fighting, with the declared aim of preventing the

establishment of a Jewish state (Morris, 2003).

The conflict between Jews and Arabs in Palestine thereby became a conflict between Israel and the Arab world, and in effect an amalgam of conflicts between Israel and its Arab neighbors. Each of these conflicts the conflict between Israel and Egypt, the conflict between Israel and Syria, and so on developed in its own direction. These conflicts were linked to each other, and all of them obviously concerned the Palestinian question. Nevertheless, each developed, escalated, and erupted into an active conflict and in the Egyptian and Jordanian cases, were resolved in its own way.

The point of departure for the Arab side in the conflict was a

determined and unequivocal refusal both to recognize Israel's right to exist in

the region and to form peaceful relations with it. The Arab refusal fed a

belief that the elimination of Israel was not only a "historic

necessity," because the Arabs regarded Israel as an aggressive entity

aiming at expansion, but also an achievable goal, even if in the long term, given

the sources of Israel’s weakness, above all a demographic imbalance in favor of

the Arab side (Harkabi, 1968).

Over the years, however, cracks appeared in the walls of enmity and

hostility surrounding Israel. De facto, the Arab world began to accept Israel's

existence and show willingness to end the conflict and establish peaceful

relations with it. The Six Day War in June 1967 and the Yom Kippur War in 1973

to a great extent paved the way to peace, because they refuted the Arab belief

that their victory was guaranteed in the long run, and that they should therefore

adhere to the status quo of neither peace nor war. It became clear to the Arabs

that if they wanted to regain the territories they had lost during the Six Day

War, and if they wanted to gain entry to the heart and coffers of the United

States in order to address their domestic social and economic problems, they

would have to achieve a peaceful settlement with Israel.

Egyptian President Anwar a-Sadat was the first to breach the Arab wall

of hostility and hatred with his historic visit to Jerusalem in November 1977. The

two sides subsequently signed a peace agreement in March 1979 (Stein, 1999).

Following the defeat of Saddam Hussein in the Gulf War in the spring of 1991

and the dissolution of the Soviet Union later that year, then-US Secretary of

State James Baker said there was a historic opportunity for promoting a political

solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict. In October 1991, a peace conference was

convened in Madrid, thereby opening a new chapter in Israel's relations with

the Arab world, followed by peace negotiations between Israel and its Arab

neighbors, including with the Palestinians (Ben-Tzur, 1997).

The Arab-Israeli political process led to the signing of the Oslo

Accords between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in

October 1993 and the signing of a peace agreement between Israel and Jordan in

October 1994. The Oslo Accords were designed to pave the way to achieve an

Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement based on mutual recognition between Israel

and the Palestinians, led by the PLO, of each side's national rights. The

process also included a multilateral channel for promoting economic cooperation

between Israel and Arab countries. Diplomatic ties were institutionalized, albeit

on a low level, between Israel and several Arab countries, including Tunisia,

Morocco, Oman, and Qatar.

The Decline

of Arab Nationalism, the Weakness of Arab States, and the Rising Power of Iran

and Turkey

The change in the Arab stance toward Israel, which eventually led to

the signing of peace agreements between Israel and some of its Arab neighbors,

took place at a time when Arab nationalism was declining as a force in the Arab

world. The death of Nasser in September 1970, the undisputed leader of Arab

nationalism at the time, preceded by the Arab defeat in the Six Day War,

spelled the end of Nasserism and Egypt's struggle under Nasser's leadership for

influence if not hegemony in the Arab world. Competing ideologies and doctrines

replaced Arab nationalism, which had failed in its attempt to unify the Arabs

and defeat Israel (Ajami, 1978/1979, 1981; Susser 2003).

The basic cause of this failure was the accumulation of domestic

social and economic difficulties afflicting large parts of the Arab world.

These difficulties stemmed from accelerated population growth, obstacles

preventing modernization and economic progress, and the backwardness of Arab

society. The Arab world was left trailing behind other parts of the globe by an

ever-increasing margin. There is no doubt that the absence of openness and

democracy also contributed to the failure (Ayubi, 1996).

The difficulties that afflicted the respective Arab countries motivated

each to lend priority to its particular national interests, and especially

those of the ruler and his regime, over the interests of Arab nationalism and a

focus on the Palestinian question. This latter issue therefore lost its

centrality and importance. The result was Arab willingness, or at least

willingness on the part of several Arab countries, to settle the conflict with

Israel and to make progress in political, security, and economic relations

(Sela, 1998).

With the threat of Iran hanging over them, many of the moderate Arab countries, such as the Gulf states, have been increasingly willing to step up their cooperation with Israel and accept help against the Iranian threat.

Israel was not the only beneficiary of the changes to the Middle East

map. In the first decade of the 21st century, two old-new regional

powers seeking to bolster their regional standing stood out: Turkey and Iran.

These countries were perceived in the region as continuing the policy of two empires:

the Ottoman Empire and the Persian-Safavid Empire (succeeded by the Qajar

Empire), which fought against each other for hundreds of years. The Ottoman

Empire controlled the Middle East for nearly 500 years, from the early 16th

century until the end of WWI, when the region fell into the hands of Western

powers, Britain and France.

Turkey and Iran now have the opportunity to try to regain their previous standing. Turkey, under the rule of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the charismatic leader of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), has succeeded in giving Turkey political stability and economic prosperity. In contrast to all other Turkish governments since Ataturk, the founder of the modern Turkish Republic, Erdogan has regarded the Arab and Muslim world, not Europe, as his preferred theater of action. He has tried to take advantage of the Islamic character of his party to promote his status and that of Turkey in the Arab world, with the help of Islamic political parties mostly those belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood movement, which took advantage of the Arab Spring to improve their standing, and in several cases achieved power and kept it for a while: Hamas in the Gaza Strip, the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and the Nahda Movement in Tunisia (Tol, 2019).

Iran has also profited from the changes in the Middle East. Tehran's

ambitions to attain influence and hegemony and to create a security zone

stretching from the Iranian mountain range to the Mediterranean shore began

decades or even hundreds of years ago. These ambitions were evident under the

shahs, who preceded the current regime of the ayatollahs. Moreover, Iran clearly

profited from the wars waged in the region by the United States, first in

Afghanistan in the winter of 2001, and then in Iraq in the spring of 2003,

which led to the collapse of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan and Saddam

Hussein's regime in Iraq. Both of these regimes were bitter enemies of Iran,

and served as a counterweight to its eastward and westward expansionist

ambitions. Of particular importance was the downfall of Saddam Hussein and the

overthrow of the Iraqi state, through which Iran now seeks to penetrate the

Fertile Crescent. The US entanglements in Afghanistan and Iraq also helped

Tehran establish itself in the vacuum that emerged after the departure of the

United States and increase its power. Since Iran is a Shiite country trying to

promote Shiite Islam and use it to consolidate its status among Shiite

communities throughout the Arab world, its rise is also perceived as the rise

of the Shiite world at the expense of the Sunni world. Iran has made strenuous

efforts to develop nuclear capability, and its involvement in terrorism and

subversion among Shiite Arab communities was designed to destabilize many Arab

countries, especially the Gulf states, such as Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and even

Kuwait. These actions have made these countries feel threatened, and have

accentuated their fear of Iran (Saikal, 2019).

With the threat of Iran hanging over them, many of the moderate Arab

countries, such as the Gulf states, have been increasingly willing to step up

their cooperation with Israel and accept help against the Iranian threat. As

early as the 1990s, in the wake of the Arab-Israeli peace process led by the

United States, a dialogue began between Israel and the Gulf states. Channels of

political and security cooperation between them were created, and trade and

economic ties, which previously had been kept on a low profile and a small

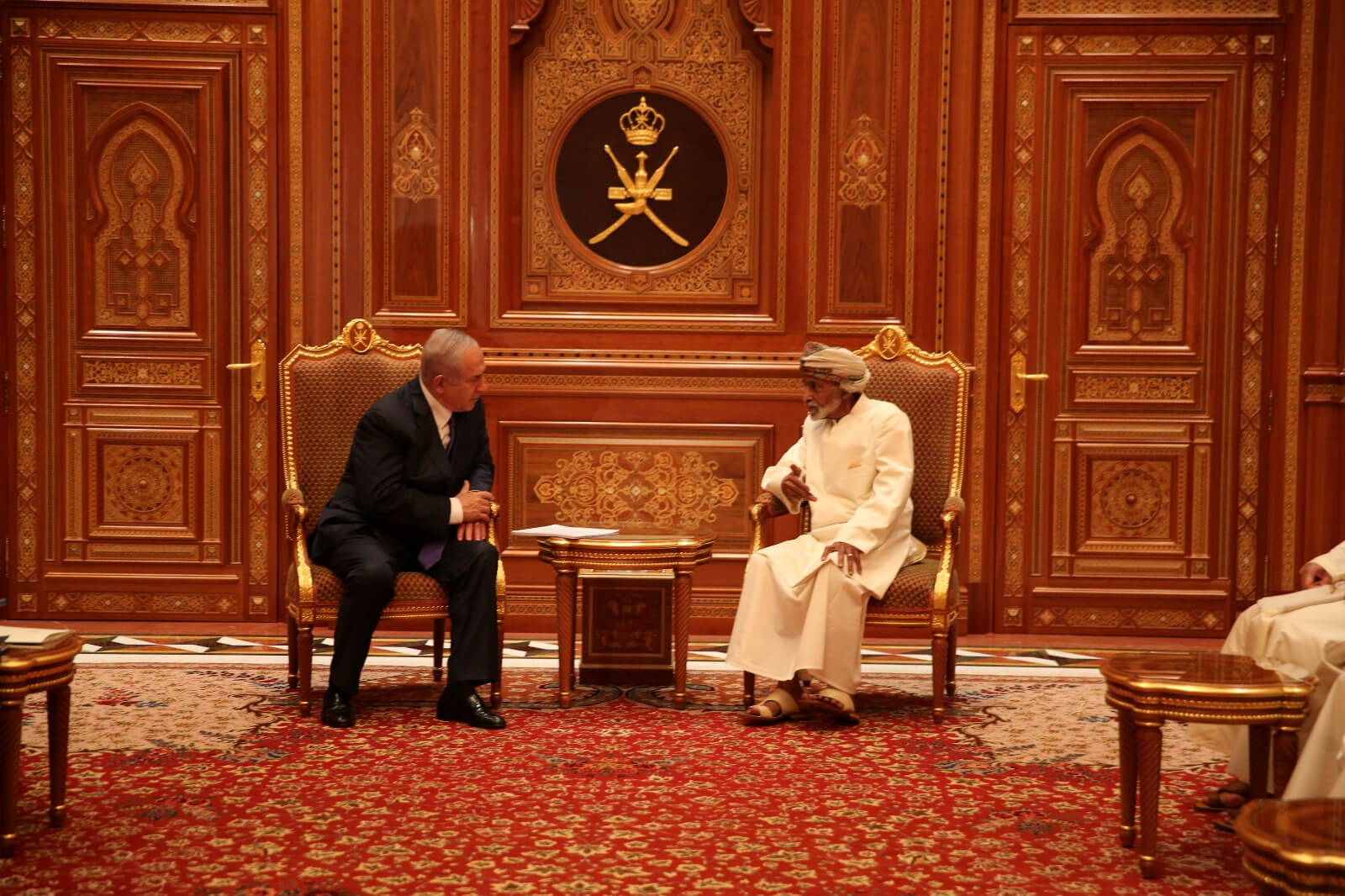

scale, were expanded. Two Gulf states, Oman and Qatar, hosted official visits

by Israeli leaders, such as the visit by Prime Minister Shimon Peres to Doha in

early 1996. Diplomatic offices were opened in Israel, and the opening of Israeli

offices in these countries was approved (Guzansky, 2009).

Israel and

the Arabs: Dialogue for Lack of Choice

Events, however, have disproved the assumption that the peace process

between Israel and its Arab neighbors has progressed beyond the point of no

return, and that achievement of peace between the parties is mainly a question

of time. In March 2000, the peace talks between Israel and Syria reached a

deadlock. Israel and the Palestinians also failed in their efforts to bridge

the gap between their respective positions. The al-Aqsa Intifada, which began

in September 2000, widened the rift between Israel and the Palestinians, and

worsened Israel's relations with many Arab countries.

The belief that a solution to the conflict is "historically

inevitable" was put to the test and disproven in 2000, not only by the second

intifada, but also by Israel's withdrawal from Lebanon after 18 years of

involvement, including the presence of the Israeli army. This withdrawal

followed Israel's failure in dealing with Hezbollah and the bloody clashes in

South Lebanon.

Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah was quick to portray Israel's unilateral withdrawal from southern Lebanon as a turning point in the history of the Arab-Israeli conflict. He claimed that Hezbollah had been able to achieve what no Arab country or army had ever achieved before the unconditional removal of Israel from territory at no cost whatsoever, let alone a settlement or peace agreement. Nasrallah further explained that what happened in Lebanon proved that economic prosperity could be achieved and maintained without peace or any commitment from Washington, and even despite American opposition. Furthermore, Nasrallah boasted that Hezbollah possessed the key, and even a blueprint, that would subsequently enable the Arabs to overcome Israel, based on the disclosure of Israel's Achilles’ heel the fatigue and exhaustion felt by Israeli society, and its excessive sensitivity to the lives of its soldiers, as shown by the war and its aftermath (Zisser, 2009).

On May 26, 2000, Nasrallah gave a victory speech in the village of Bint Jbeil, from where the IDF had withdrawn a few days previously. This has become known as the "spider web" speech, in which Nasrallah bragged, "Several hundred Hezbollah fighters forced the strongest state in the Middle East to raise the flag of defeat…The age in which the Zionists frightened the Lebanese and the Arabs has ended…Israel, which possesses nuclear weapons and the most powerful air force in the region this Israel is weaker than a spider's web" (Hezbollah, 2000).

The results of the Second Lebanon War in the summer of 2006 ostensibly provided support for Hezbollah's perception of Israel's weakness. Although the war was far from a Hezbollah victory, the organization saw quite a few achievements, and also exposed the limits of Israel's power and several of its weaknesses (Harel & Issacharoff, 2008). Indeed, in his "divine victory" speech on August 2006, following the end of the war, Nasrallah said that the war was a historic turning point in the chronicles of the Arab-Israeli conflict (Hezbollah, 2006). The takeover of the Gaza Strip by Hamas in February 2007 was also regarded in the Arab world as proof of the reversal of the trend from reconciliation and acceptance back to hostility and enmity, and especially the withdrawal from previous Arab willingness to reconcile with Israel.

The failure to progress toward an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement, followed by the outbreak of the second intifada, halted progress in relations between Israel and Arab countries, and even reversed progress that had been made. At the same time, Israel's peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan survived the challenge, as did the channels of communication between Israel and other Arab countries, headed by the Gulf states. Led by Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states invested considerable effort in an attempt to revitalize the peace process and achieve progress. As part of this effort, they proposed various initiatives, most prominently, the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative (API). This initiative was designed to break the deadlock in the peace process, with the Arab countries providing the Palestinians with backing and sponsorship, thereby making it easier for the Palestinians to accept painful compromises, while guaranteeing Israel what it sought normalization in its relations with the entire Arab and Muslim world (Fuller, 2002). The API, however, was far from meeting the requirements of the Israeli government, which did not accept it. Later, during the Second Lebanon War between Israel and Hezbollah, many of the Gulf states, among others, almost openly supported the Israeli stance and military operations against Hezbollah in Lebanon. Finally, as the first decade of the 21st century drew to a close, with the possibility of an Israeli attack on Iran's nuclear facilities to prevent Iran from attaining nuclear capability, many Arab countries again supported Israel, albeit tacitly and indirectly (Kedar, 2018).

The Gulf states, headed by Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab

Emirates, regard Iran as a concrete, immediate, and mounting threat. Iran has challenged

them on their own territory or in their immediate neighborhoods, i.e., not only

in remote theaters such as Lebanon, where Hezbollah has labored to impose

itself on the country's political system and challenge the Sunni population and

its leaders, most of whom were sponsored by Saudi Arabia, such as Saad el-Din al-Hariri

(for example, Hezbollah's takeover of West Beirut in May 2008). Nor was it

confined to Syria, led by the Alawite Assad dynasty, which adhered to its

strategic alliance with Tehran, nor even to Iraq, where Iranian influence

struck deep roots among the country's Shiite population.

This was apparently the background for the bolstering and expansion of the dialogue between Israel and several of the Gulf states, headed by Saudi Arabia. The media reported signs of covert cooperation between Israel and Saudi Arabia as part of the two countries' effort to thwart the Iranian nuclear program. For example, meetings were reported between Israeli leaders, including Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, and a Saudi leader, probably Prince Bandar bin Sultan, a former director general of the Saudi Intelligence Agency. It was also reported that Mossad head Meir Dagan visited Riyadh. There were many media reports of an effort to achieve security coordination between the two countries for a possible Israeli military operation against Iran's nuclear facilities (Israel Held Secret Talks, 2006).

At the same time, modest progress was also made in Israel's economic relations with the Gulf states. In the first decade of the 21st century, the Gulf states became the third largest destination for Israeli goods in the Middle East, after the PA and Turkey. Trade with these countries was conducted primarily through third parties, which makes it difficult to obtain up-to-date statistical information, but it has been estimated at over $500 million annually, and presumably the true extent is greater than reported. The media also occasionally reported that companies producing security products know-how, technology, or weapons were conducting large-scale connections with these Gulf states. This trend toward economic cooperation gained momentum as Israel became a global leader in cyber intelligence (Zaken, 2019; Atkins, 2018; Levingston, 2019).

The Fall of

the Arab Spring

The so-called Arab Spring, which began in December 2010, was a turning

point in the history of the region that greatly changed the prevailing order,

including relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors. The Arab Spring

destabilized many of the Arab countries, overthrowing several regimes that had

been in power for decades. At its height, it seemed to pose a challenge to the legitimacy

of the borders and the 20th century political order in the Arab

world that were determined at the San Remo conference in April 1920 (Michael

& Guzansky, 2016). In addition, at least momentarily, it seemed that the

Arab world was following the example of other parts of the world, such as

Eastern Europe and South America, where politically active young people led a

movement for change and even democracy. The term to describe the upheaval in

the Arab world, "Arab Spring," originated in discourse in the media

and among Western academics, reflecting the hope that this unrest would

overthrow the prevailing political and social order in the Arab world, and propel

Arab societies toward democracy and enlightenment that would culminate in

political stability, economic prosperity, security, and social justice (Bayat,

2017). The Middle East, however, marches to its own drum, and the

liberal-progressive wave gave way to an Islamic wave promoted by the forces of

Islam in the region. The protests and revolutions were later succeeded by bloody

civil wars that caused instability, insecurity, and chaos (Govrin, 2016; Podeh

& Winckler, 2017; Rabi, 2017).

The regimes of Zine el-Ben Ali in Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt were

overthrown. The Islamic political parties took power briefly, but both of these

countries eventually returned to their starting point of before the Arab

Spring. In Tunisia, some of the secular forces that regained power had been

part of Ben Ali's government. In Egypt, the army took power in June 2013 in a

military coup led by Minister of Defense Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, overthrowing the

Muslim Brotherhood government led by Mohamed Morsi. In Libya and Yemen, on the

other hand, the overthrow of the regimes led to the collapse of the

nation-state and the outbreak of bloody civil wars.

In Yemen, forces loyal to the Houthi movement (named for its founder,

Hussein al-Houthi), which belongs to the Zaidi Shi'ite faction, gained control

of Sanaa, the capital of Yemen. Iran became the Houthis' main supporter in

their battle for control of Yemen, located in Saudi Arabia's backyard. Riyadh has

long feared a scenario of Yemen becoming an Iranian frontline, from which it

could threaten Saudi cities with missile barrages and blockade shipping in the

Bab el-Mandeb Strait at the entrance to the Red Sea. Fear of the Houthis and

Iran, which increased its involvement in Yemen with the help of Hezbollah,

united the Gulf states, led by Saudi Arabia. In March 2015, the Gulf states launched

Operation Decisive Storm, an aerial offensive aimed at preventing the Houthis

from taking over Yemen and denying Iran the stronghold it hoped to acquire in

the southern Arabian Peninsula and at the entrance to the Red Sea. Saudi

Arabia, however, was unable to achieve victory, and became entangled in a

prolonged war in Yemen that exacerbated the security challenges created by the aid

given by Iran to the Houthis (Gordon, 2018). The statement by Israeli Prime

Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in October 2019 that Iran had stationed advanced

missiles in Yemeni territory capable of hitting Israeli targets showed that

Yemen had become a source of concern not only for Saudi Arabia, but for Israel as

well (Eichner, Friedson, & Fuchs, 2019).

In Syria, Bashar al-Assad held on to power, but In his struggle for

survival he dragged his country into a prolonged and bloody civil war in which

over half a million Syrians were killed and millions more fled the country,

becoming refugees. More important was the fact that Bashar al-Assad's victory

was achieved because in September 2015 Russia and Iran entered the war on his

side. These two countries' involvement gave them influence and control over

events in Syria (Zisser, 2020).

Moscow was thereby able to play a key role in shaping the map of the

region and designing its image according to Russia's interests and historic

goals in the Middle East. Moscow's rise came at the expense of Washington. In

the end, the outbreak of the Arab Spring signaled the end of a prolonged Pax

Americana in the Middle East that began following the Gulf War in the spring of

1991 and gained greater force when the Soviet Union disintegrated in December

of that year. Under both the Obama and the Trump administrations, it was

believed that the United States wanted to sever itself from the region and its

problems.

Russia did not operate in a vacuum, and was not the only power in the region. Iran and its satellites, which are all part of the radical Shiite axis that has emerged in the Middle East in recent decades, served as a platform and a helpful partner for Russia in the resumption of its place in the Middle East. Ironically, the Arab Spring, which many in and outside the region regarded as the rejuvenation of the Sunni Arab world in response to the Shiite challenge facing it, has strengthened the Shiite axis, instead of weakening it. Together with Russia, and in close cooperation with it, Iran has become an important element in large parts of the Middle East, and is perceived by many inside and outside the region as an actor contributing to stability in the Middle East, even while and at the price of promoting Tehran's goals in this region (Bolan, 2018). Tehran has thus been able to take advantage of the chaotic situation in the region to consolidate its grip in Iraq and Syria, and even in Yemen. Many Arab countries, especially Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, regard the strengthening of Iran as a threat. They turned to Israel because they regard it as an important regional actor, and also as a possible ally and partner, against the growing threat of Iran.

Initially Israel was thought likely to suffer as a result of the Arab

Spring, which led to the overthrow of regimes regarded as its allies, above all

the Mubarak regime in Egypt. The emerging trend in the early years of the Arab

Spring toward strengthened Islamic movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood,

which gained power in Egypt and ruled there for about a year, was also regarded

as a negative development liable to pose a threat to Israel. However, the chaos

that took hold in the Arab world, and the efforts by Arab regimes to retain

power despite the threats they faced, strengthened Israel's position, and led a

few Arab countries, notably Saudi Arabia and several other Gulf states, as well

as Egypt and Jordan, to cooperate with Israel on matters of interest and

importance. This cooperation was highly reminiscent of the alliance of the

periphery, and in a more practical way, Israel's covert cooperation in the late

1950s, including in intelligence and security, with Ethiopia, Turkey, and Iran

against the rising power of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel al-Nasser (Alpher,

2015). This time, however, the cooperation was not aimed against Egypt, which

instead was an important partner in this web of relations, together with other

countries that joined forces against the threat of Iran, perhaps also against

Turkish ambitions of hegemony, and in an effort to combat and halt the Islamic

terrorism that has surfaced in the Arab world.

Turkey, the largest Sunni Muslim country, albeit not an Arab country,

could have served as an axis for a general regional campaign by moderate

pro-Western Sunni states aimed at countering and halting Iran. This, however,

did not occur. Turkey’s close alliance with Israel in the early 1990s came to

an end with Erdogan's rise to power. Turkey tried to use the Arab Spring and

ride the Islamist wave that appeared likely to sweep the Arab countries. The

defeat of the Muslim Brotherhood, however, was also a defeat for Turkey, which

was left with an unsated appetite. In any case, Erdogan, who more than once has

subordinated Turkish foreign policy to his personal fancies or personal

political interests, prevented Turkey from using the crisis to strengthen its standing,

even though Ankara has expressed dissatisfaction with the strengthening of

Iran, Turkey's biggest Shiite and regional competitor (Schanzer &

Tahiroglu, 2016).

This cooperation can lay the groundwork for more extensive regional cooperation in the Mediterranean Basin by both Israel and the Arab countries with other players. One such example is the developing connection between Israel and Egypt with Cyprus and Greece.

One example of this was Ankara's policy toward Israel and Egypt, two important regional actors. Due to Turkey's use of the Palestinian issue, its relations with Israel plummeted, and a prolonged rift began following the Mavi Marmara flotilla incident, followed by Erdogan's wild anti-Israeli rhetoric. In relations with Egypt, Erdogan refused to recognize the legitimacy of the military coup led by el-Sisi against the Muslim Brotherhood government in June 2013. This caused a rupture and severance of relations between the two countries. Turkey's growing intervention in the war in Libya in the last months of 2019 and its attempt to establish facts on the ground concerning ownership of territorial waters in areas adjacent to Egypt, which includes the proposed natural gas pipeline from Israel via Cyprus to Europe, again heightened the tension between Cairo and Ankara, and threatened to involve Israel in this dispute (Ben-Yishai, 2019). The vacuum created in the region and the Iranian and some will also say Turkish threat have forced Israel and the other countries to step up the cooperation between them (Jones & Petersen, 2013). In this case, as with the alliance of the periphery 60 years earlier, there is no formal and official alliance; what is involved is a covert web of cooperation, mostly in intelligence and security. Israel has taken advantage of the war in Syria to attack arms deliveries that Iran tried to send to Hezbollah through Syria, and later targeted the bases established by Iran on Syrian territory for the Revolutionary Guards al-Quds force, or for the Shiite militias it brought to Syria. Israel has been at least partly successful in this campaign, since Iran has hesitated to embark on an all-out direct conflict with it. Iran withdrew its forces slightly from the Israeli-Syrian border, and also refrained from moving forward with the consolidation of its forces in deep within Syrian territory. Israel's determined struggle against Iranian consolidation in Syria is believed to be effective and to have deterred Iran, and for the time being has also hindered if not halted Iranian consolidation in Syria. It has thereby provided a model and example for other countries, which have been inspired by Israel's willingness to confront Iran (Byman, 2018). Needless to say, the tightening of relations between Israel and the Gulf states was validated and rendered more significant by President Trump's intention to withdraw United States forces from Syria as part of a general US disengagement from the Middle East, a measure already begun by President Obama (Hall, 2019). Washington's reluctance to respond in the summer of 2019 to Iranian acts of aggression against the Gulf states merely augmented their reliance on Israel. Even when the United States killed al-Quds force commander Qasem Soleimani in Iraqi territory in early January 2020, many of the Arab countries gave Israel credit for the act.

To be sure, this Arab-Israeli cooperation is subject to constraints

and weaknesses and a glass ceiling that the parties will have difficulty in

overcoming, especially in the absence of any progress in the political process

between Israel and the Palestinians. Some in Israel believe that this

cooperation rests on shifting sands, and is regularly threatened by well-grounded

relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors, and certainly by public

opinion and elite circles in these countries, in contrast to the defense

establishments, which favor this cooperation.

Nevertheless, the burgeoning cooperation between Israel and the Arab countries shows how the Middle East has changed, and the transformation in Israel's relations with the Arab world from enmity and hostility to acceptance, readiness to live in coexistence, and cooperation on essential strategic interests of many Arab countries. Furthermore, this cooperation can lay the groundwork for more extensive regional cooperation in the Mediterranean Basin by both Israel and the Arab countries with other players. One such example is the developing connection between Israel and Egypt with Cyprus and Greece.

Another example is the unprecedentedly close military cooperation

between Israel and Egypt in combating the threat posed by the branch of the

Islamic State operating in the Sinai Peninsula. Israel reportedly attacked Islamic

State targets in Sinai in cooperation with the Egyptian army, and supplied the Egyptian

army with intelligence information for assistance in the campaign against

Islamic extremists. The Egyptian public has not changed its attitude toward

Israel, but there is no doubt that the Egyptian government has become more

committed and willing to undertake unprecedented cooperation with Israel in the

military and intelligence spheres (Egypt, Israel in Close Cooperation, 2019). Jordan

has also tightened security, and even military, cooperation with Israel,

following efforts by the Islamic State to gain a foothold in the

Syrian-Jordanian border strip, but also in view of Iran's plans to consolidate

its grip near Jordanian territory.

Cooperation is also expanding between Israel and the Gulf states,

headed by Saudi Arabia (Melman, 2016). Along with closer security and

intelligence ties, a political dimension has been added to these relations

(Jones & Guzansky, 2019), for example, with Israel's willingness to come to

Riyadh’s aid in relations with the US administration following the murder of Saudi

journalist Adnan Khashoggi, which was attributed to Crown Prince Mohammed bin

Salman. Israel also expressed readiness to help Sudan following a historic

meeting in February 2020 in Entebbe, Uganda between Prime Minister Benjamin

Netanyahu and Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, Chairman of the Sovereignty Council of

Sudan (Netanyahu Says Israeli Airliners Now Overflying Sudan, 2020). For their

part, the Arab countries helped Washington promote the Trump administration’s “deal

of the century” as a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and were

willing to pressure the Palestinians to accept the proposal, which involves

painful compromises for the Palestinians (Caspit, 2018). To the Palestinians'

dismay, the response of some Arab countries to the publication of the American

peace plan in late January 2020 was moderate, and even friendly. The Arab

countries were not deterred by the fact that the Trump administration was

regarded as committed to Israel, or by the measures it took even before the

plan was published, such as moving the American embassy to Jerusalem,

recognizing the Israeli presence in the Golan Heights, and stating that the

Israeli settlements in the West Bank did not constitute a breach of

international law (Ravid, 2017).

The Palestinian issue has therefore ceased to be a burning question, and no longer constitutes a barrier to all progress in relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors. It still casts a shadow over such relations, however, and as such constitutes an obstacle that is hard to overcome.

Joining the enhanced military cooperation, and to some extent also

political cooperation, is economic cooperation, which has expanded as a result

of the discovery of offshore natural gas fields in the Mediterranean Sea.

Israel was the first to discover and make use of gas fields, which made it an

important player. Israel became a supplier of natural gas to Jordan, after

having already committed in the 1994 peace treaty to supply water to Jordan, and

it has increased the water quota over the years. Israel also signed agreements

to supply gas to Egypt. Israel's efforts to leverage these discoveries to

improve its relations with Turkey have been unsuccessful, as Erdogan's

hostility has prevented any agreement for exporting gas to Europe via Turkey.

As a substitute, Israel chose the Greek-Cypriot channel for gas exports to

Europe. These economic ties were part of a deeper set of ties, unquestionably

motivated by the three countries' anxiety about Turkey under Erdogan's

leadership (Karbuz, 2017).

The system of regional alliances that Israel hopes to create is not

limited to moderate Sunni Arab countries. Together with its connection to

parties in the region such as the Kurds and South Sudan, which have

historically been allies of Israel, Israel has also strengthened its

connections with Cyprus and Greece, as well as Egypt. These relations carry

economic weight, due to the desire to develop joint energy resources,

especially offshore gas fields in the Mediterranean Sea. These relations have a

security dimension as well, due to the anxiety about Turkey shared by Cyprus

and Greece and the hostility between Cairo and Ankara (Macaron, 2019). Some

also regard Israel's ties with countries such as Azerbaijan, Greece, Cyprus,

Ethiopia, South Sudan, Chad,

and other Asian and Africa countries as a continuation of the historical

alliance of the periphery in the 1950s.

Nevertheless, the shadow of the conflict with the Palestinians continues to hamper the effort to improve Israel's relations with the Arab countries (Black, 2017). One example is the chill in relations between Jordan and Israel. Amman refrained from celebrating the 25th anniversary of the peace agreement between the two countries, and demanded the return of the enclaves in its territory cultivated by Israeli farmers at Tzofar in the Arava region and at Naharayim. This deterioration in relations was a result of pressure from public opinion in Jordan, but also recognition by the Jordanian government itself that progress toward a solution of the Palestinian question is a critical issue for the kingdom not necessarily out of concern about the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, but out of concern that continuation of the conflict, or even the possibility that Israel will annex parts of the West Bank, is likely to pose a real threat to Jordan's stability and prompt a new wave of Palestinian refugees to Jordan and the possibility that the Palestinian national movement will seek to focus its efforts and activity in Jordan itself (Landau, 2019; Gal & Svetlova, 2019).

Conclusion

Over the 72 years since its founding, Israel’s relations with the Arab world have changed completely. Hostility and enmity have given way to acceptance; willingness to live in coexistence even if only for lack of choice; and relations of cooperation with strategic implications.

In the early decades of Israel's existence, Arab nationalism and its

undisputed leader, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel al-Nasser, were perceived as

enemies and the principal threat to Israel. Today, Iran is the reference threat

for both Israel and many of its Arab neighbors. For this reason, the Arab

countries with which Israel was in a prolonged and apparently unsolvable

conflict, among them both Egypt and Saudi Arabia, became allies because of the

Iranian threat, and to a lesser degree because of the Turkish challenge.

At the same time, this cooperation with Arab countries has clear limits

involving the lack of ability, and probably also the lack of desire, to make

these relations public and extend them beyond security relations between

rulers, governments, and defense institutions to normalization and a friendly

peace between peoples.

An interesting question is whether the process is reversible,

particularly in view of the fact that recognition of the importance of ties

with Israel is confined to the Arab rulers, and particularly the security and

military establishments behind the rulers. In contrast, popular opinion remains

hostile to Israel, although it does not advocate a conflict with it, as it did

in the Arab world in the 1950s and 1960s. This basic hostility, however, is fed

by the absence of progress in negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians,

as well as the perception of Israel as a non-Arab and non-Muslim foreign entity

in the region that sometimes looms as a threatening opponent. This attitude

constitutes a kind of glass ceiling hampering any effort to promote and enhance

relations between Israel and the Arab world (Miller & Zand, 2018).

The Palestinian issue has therefore ceased to be a burning question,

and no longer constitutes a barrier to all progress in relations between Israel

and its Arab neighbors. It still casts a shadow over such relations, however,

and as such constitutes an obstacle that is hard to overcome. While Arab

countries are no longer willing to subordinate their national and political

interests to the Palestinian cause, and may also be willing to expand their

relations with Israel even without a resolution to the Palestinian issue, they

need calm and stability, and keeping this issue under the radar is a definite

necessity for this purpose.

The Palestinian question remains a low common denominator for Arab

public opinion in its search for identity and meaning, as well as a tool

exploited by opposition groups and opponents of the regime in Arab countries to

bait their rulers. The Palestinian issue is the sole issue around which it is

possible to unite without fear of a rift or dispute between Arab communities in

the Arab world or outside it, including expatriate Arab and Muslim communities,

for example, Arab intellectuals and students on campuses in Western higher

education institutions. This issue is the only one that can still trumpet the

Arab identity that is still essential for many groups in the Arab world, and

certainly among expatriates; hence the reason for the sensitivity of this issue

among Arab rulers and regimes. In the absence of any chance of achieving an

Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement in the foreseeable future, the Palestinian

issue will continue to cast a shadow on the effort to promote normalization and

deeply rooted connections between Israel and the Arab countries. The truth is

that peace currently appears more distant than ever, given the unbridgeable

gaps between the parties' positions; the absence of leadership that is committed

to peace, believes in it, and is willing to take risks to achieve it; and the

hardening of Israel's positions, such as the disavowal among many of a

commitment to the two-state solution and the desire to annex territory in the

West Bank, including the Jordan Valley.

Current relations between Israel and the Arab world reflect the

changing face of the Middle East and the fundamental processes it has

experienced, above all the fading of Arab nationalism and the decline of the

Arab world, coupled with the rise in the influence and power of Iran and

Turkey. These two powers are now dictating the path of the Middle East. The

Arab Spring did not directly cause this development, but it unquestionably

accelerated it. Cooperation between Israel and the Arab countries, especially

with the Gulf states, may focus on Iran, but it also has the potential to

develop beyond the struggle against Iran, because both sides share additional

political and security interests. It reflects Israel's transformation, not only

from an ostracized state into a state accepted by the Arab world, but also from

a marginal and weak country into a powerful actor that everyone in today's

Middle East must take into account.

A wise policy by Israel's leadership, as well as by Israel's partners

in the system of relations and given the understandings now emerging in the

Middle East, is likely to enhance stability and promote peace efforts in the

region, or at least dialogue and reconciliation. No less important, it is

likely to yield substantial economic benefits for all of the regional actors.

On the other hand, the use of these relations to enshrine the status quo and

preserve it, or even to initiate conflict, in contrast to defense and

deterrence against common enemies, is liable to aggravate instability in the

region, and to lead to cycles of violence. For example, the drawbacks of unilateral

measures such as Israel’s annexation of territory in the West Bank, while

taking advantage of its edge over the Arab countries, even those with which there

is cooperation, are likely to outweigh the benefits. Israel should also act

with moderation and caution from a stance of legitimate defense in its conflict

with Iran and its political friction with Turkey, not from an assertive and

adventurous stance. Otherwise, a heavy shadow will be cast over the relations

that Israel has formed with its neighbors, which are far more significant than mere

acceptance of Israel's existence for lack of choice. These relations are still

not sufficiently stable and established; they rest exclusively on regime and

state interests, and lack a base in broad public support in Arab public

opinion.

References

Ajami, F. (1978/79,

winter). The end of pan-Arabism. Foreign Affairs.

https://katzr.net/92e650

Ajami, F. (1981). The

Arab predicament: Arab political thought and practice since 1967.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Alpher, Y. (2015). Periphery:

Israel's search for Middle East allies. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

A-Sharaa, F. (1999,

December 17). Fundamental principles for peace. Tishreen [in Arabic]

A-Sharaa, F. (2000,

February 12). Speech by Farouk a-Sharaa. a-Safir [in Arabic]

Atkins, J. (2018, August 16). Israel’s exports to Gulf states worth almost $1 billion, study suggests. i24news. https://katzr.net/ca57ad

Ayubi, N. N.

(1996). Over-stating the Arab state: Politics and society in the Middle East.

I. B. Tauris.

Bayat, A. (2017).

Revolution without revolutionaries: Making sense of the Arab Spring.

Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bentzur, E. (1997).

The road to peace goes through Madrid. Tel Aviv: Yediot Ahronot. [in Hebrew].

Ben-Yishai, R.

(2019, December 24). The new oil and gas wars in the Middle East. Ynet.

https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5647439,00.html [in Hebrew].

Black, I. (2017). Enemies

and neighbors: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017. Atlantic

Monthly Press.

Bolan, C. J. (2018,

December 20). Russian and Iranian “victory” in Syria: Does it matter? Foreign

Policy Research Institute. https://www.fpri.org/article/2018/12/russian-and-iranian-victory-in-syria-does-it-matter/

Byman, D. L. (2018,

October 5). Will Israel and Iran go to war in Syria? Brookings Institute. https://katzr.net/aeca3f.

Caspit, B., (2018,

October 18). Analysis: Israel torn between Saudi Arabia, Turkey on Khashoggi affair.

al-Monitor. https://bit.ly/3fQYifK

Egypt, Israel in close

cooperation against Sinai fighters: Sisi. (2019, January 5). al-Jazeera.

https://katzr.net/c0644b

Eichner, I. (2019,

October 28). "Netanyahu: Iran's precision missiles in Yemen meant to attack

Israel," Ynet, https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-5614949,00.html

Fuller, G. E.

(2002). The Saudi peace plan: How serious?" Middle East Policy Council,

9(2). https://www.mepc.org/saudi-peace-plan-how-serious

Gal, Y., & Svetlova,

K. (2019). 25 years of Israel-Jordan peace: Time to restart the relationship. Mitvim

Policy Paper.

Gordon, P. (2018 November

12). Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen has failed. The Washington Post.

https://katzr.net/d68f02

Govrin, D. (2014). The

journey to the Arab Spring: The ideological roots of the Middle East upheaval

in Arab liberal thought. Middlesex: Vallentine Mitchell Publishers.

Guzansky, Y. (2009).

Israel and the Gulf states: A thaw in relations? INSS Insight, 133.

Hall, R. (2019, January

3). Trump says Syria is “sand and death” in defence of troop withdrawal. The

Independent. https://katzr.net/40f3bc

Harel, A., & Issacharoff,

A. (2008). 34 days: Israel, Hezbollah, and the war in Lebanon. Palgrave

Macmillan.

Harkabi, Y. (1974).

Arab attitudes to Israel. Transaction Publishers.

Harris, W. (2018). Quicksilver

War: Syria, Iraq and the spiral of conflict. Oxford: Oxford University

press.

Hezbollah, Archive

of Nasrallah's speeches. (2000 May 26). https://video.moqawama.org/sound.php?catid=1 [Arabic recording].

Hezbollah, Archive

of Nasrallah's speeches (2006, August 16). https://video.moqawama.org/sound.php?catid=1 [Arabic recording].

Jones, C., &

Guzansky, Y. (2019). Fraternal Enemies: Israel and the Gulf Monarchies. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Jones, C., & Petersen,

T. (Eds.). (2013). Israel's Clandestine Diplomacies. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Karbuz, S. (2017). East

Mediterranean gas: Regional cooperation or source of tensions? Barcelona Center

for International Affairs. https://katzr.net/d0af00

Kedar, M. (2018,

November 8). Behind the scenes of the warmer relations between Israel and the

Gulf states. Mida. https://katzr.net/595c95/ [in

Hebrew].

Landau, N. (2019, October

13)."25 years since Israel-Jordan peace, security cooperation flourishes, but

people kept apart. Haaretz. https://bit.ly/2Z7ZGUF

Levingston, I.

(2019, July 24). Israel and Gulf states are going public with their relationship.

Bloomberg Businessweek. https://katzr.net/66c4d1

Macaron, J. (2019).

The Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum reinforces current regional dynamics. Arab

Center Washington DC (ACW). https://katzr.net/e5dcd4

Melman, Y. (2016, June

17). Under the radar: The secret contacts between Israel and Saudi Arabia have moved

up a notch. Forbes. http://www.forbes.co.il/news/new.aspx?Pn6VQ=EG&0r9VQ=EHJHL [in Hebrew].

Michael,

K., & Guzansky, Y. (2017). The Arab world on the road to state failure.

Tel Aviv: Institute for National Security Studies.

Miller, A. D., & Zand, H. (2018, November 1). Progress without peace in the Middle East. The Atlantic. https://katzr.net/3642bd

Morris, B. (2001). Righteous

victims: A history of the Zionist–Arab conflict, 1881–2001. First Vintage.

Netanyahu says

Israeli airliners now overflying Sudan. (2020, February 17). al-Jjazeera.

https://katzr.net/9b92f0.

Podeh, E., &

Winckler, O. (Eds.). (2017). The third wave: Protest and revolution in the

Middle East. Carmel. [in Hebrew].

Rabi, U. (2017). Back

to the future: The Middle East in the shadow of the Arab Spring. Resling [in

Hebrew].

Rabinovich, I.

(2004). Waging peace: Israel and the Arabs, 1948-2003. Princeton:

Princeton University Press.

Ravid, B. (2017,

May 16). Gulf states offer unprecedented steps to normalize Israel ties in exchange

for partial settlement freeze. Haaretz. https://bit.ly/3fWFRX9

Saikal, A. (2019). Iran

rising: The survival and future of the Islamic Republic. Princeton: Princeton

University Press.

Schanzer, J., &

Tahiroglu, M. (2106, January 25). Ankara's failure: How Turkey lost the Arab

Spring. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/turkey/2016-01-25/ankaras-failure.

Sela, A. (1998). The

decline of the Arab-Israeli conflict: Middle East politics and the quest for regional

order. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Stein, K. W.

(1999). Heroic diplomacy: Sadat, Kissinger, Carter, Begin and the quest for

Arab-Israeli peace. London: Routledge.

Susser, A. (2003).

The decline of the Arabs. Middle East Quarterly, 10(4), 3-15.

Tol, G. (2019,

January 10). Turkey’s bid for religious leadership: How the AKP uses Islamic soft

power. Foreign Affairs. https://fam.ag/3ewcFpB

Zaken, D. (2019,

July 1). Bahrain conference showcases Israeli ties with Gulf states. al-Monitor.

https://bit.ly/2NoWSgr

Zisser, E. (2009).

Hizbollah: The battle over Lebanon. Military and Strategic Affairs, 1(2),

47-59. https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/FILE1268647392-1.pdf

Zisser, E. (2020). The

rise and fall of the Syrian revolution. Tel Aviv: Maarachot [in Hebrew].