Strategic Assessment

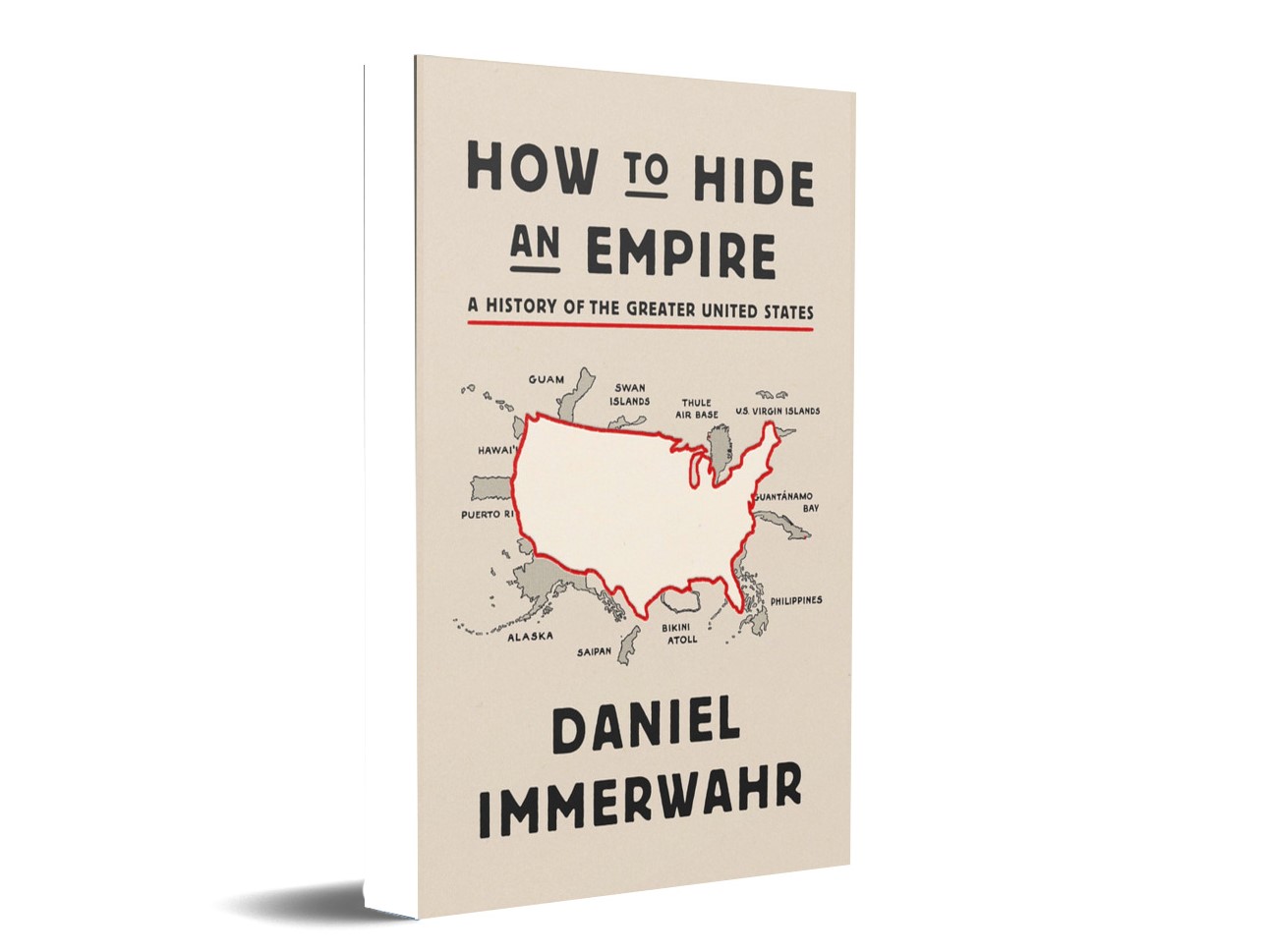

When one thinks of the age of colonialism, one generally thinks of the British Empire, the French colonial empire, Spain and Portugal, and perhaps even imperial Germany and Japan. However, Daniel Immerwahr, in How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States, discloses and examines the mostly overlooked empire of the United States.

- Book: How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States

- By: Daniel Immerwahr

- Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Year: 2019

- pp: 528

When one thinks of the age of colonialism, one generally thinks of the British Empire, the French colonial empire, Spain and Portugal, and perhaps even imperial Germany and Japan. However, Daniel Immerwahr, in How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States, discloses and examines the mostly overlooked empire of the United States.

How to Hide an Empire recalls the United States’ history of colonialism and its transition to a “pointillist empire” (p. 56). The book is arranged in two parts: The first part, “The Colonial Empire,” encompasses 12 sections recalling the history of US colonial expansion on the continent from the Louisiana Purchase to annexation of Native American lands. It then incorporates the history of US colonization overseas: the Philippine Islands, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and Alaska, and the changes in these places brought about by World War Two. The second part, “The Pointillist Empire,” details the transition from a colonial to a pointillist empire. In nine sections, Immerwahr explains the impact of WWII on the establishment of US military and logistical bases worldwide, the global standardization of manufacturing, and the spread of English as a lingua franca. In addition, he draws the connection between new technologies in chemistry, plastics, aviation, and radio, and discusses how these enabled the US to decolonize its overseas territories, while still maintaining a strategic presence.

The literature on colonialism and postcolonialism is prolific. Much has been written on the topic, from Edward Said’s “othering” in Orientalism to the arrested economies of the developing world, explained in Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Immerwahr adds to this conversation, recounting the US westward expansion and its colonization of the Philippines and Puerto Rico with imagery and new insights. Furthermore, Immerwahr illuminates the new imperial system of military bases and strategic access that the US enjoys throughout the world. David Vine, Catherine Lutz, and others have written on the topic of US foreign bases, but those texts were highly critical of US policy. Immerwahr is more nuanced. Without undue bias or nonchalance, he recognizes the benefits of the system in promoting regional stability as well as local economies; however, Immerwahr is also quick to point out that foreign bases bring unwanted US culture, unruliness of off duty soldiers, and an outsized influence on the hosting countries’ foreign policy due to the security relationship.

Immerwahr, an associate professor of history at Northwestern University in Illinois, reminds us that most Americans don’t know the history of the United States as a colonial empire. More to the point, Americans believe that the United States, though the global superpower since WWII, does not seek an empire status. Immerwahr may agree, but with caveats. After WWII, the US was no longer a colonial empire, having given up the Philippines; granted Hawaii and Alaska statehood; and eventually put in place partial self-rule for Guam, the Northern Marianas, American Samoa, and Puerto Rico with elections of their own respective governors under the President of the United States as head of state. However, after WWII, the United States, transformed from a territorial empire into a hegemonic empire, with over 800 military bases around the globe and strategic access for military bases, seaports, and airfields in tens of partner nations. This is a veritable empire of points without most of the political pitfalls or any of the economic costs of colonies. The United States had become something new in world history, what Immerwahr calls a pointillist empire.

Immerwahr introduces us to the “logo map” of the United States (p. 3). The familiar map is a representation of the forty-eight contiguous states sometimes with Alaska and Hawaii displayed in corner boxes. It does not include Puerto Rico, Guam, the US Virgin Islands, or the hundreds of mostly uninhabited islands under US auspices. When the US colonial portfolio was at its largest and included the Philippine Islands, the territories not represented on the logo map had a population of over 135 million people.

America’s colonial goals often conflicted with the racial chauvinism popular at the time. After the Mexican-American War, some in Congress wanted to annex Mexico. However, many argued, including South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun, that the United States should not incorporate “any but the Caucasian race” (p. 77). They found a compromise and annexed only the low populated areas of today’s America’s southwest, leaving the rest of Mexico for Mexicans.

At one time the United States had claims to over 100 Pacific and Caribbean Islands. Many of these islands were acquired under the 1856 Guano Island Act, which allowed US citizens to lay “peaceful” claim to uninhabited islands not claimed by another government and containing large guano deposits. Guano was needed for its nitrogen, a key ingredient in fertilizer. These Islands fell short of becoming territories. They became, according to the act, “considered as appertaining” to the United States (p. 51). Immerwahr shares a personal connection to the narrative when he tells the story of his great grandmother, Clara Immerwahr - the wife of Fritz Haber, of the Haber-Bosch process - a German-Jewish chemist whose work in synthesizing ammonia directly from air eliminated the need for nitrates from guano islands. However, the US did not relinquish claims to these islands, which became invaluable during WWII, as many of these islands acquired airfields essential for the US island hopping strategy.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Spain’s wealth and colonial control were in decline. Several Spanish colonies, including Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico, were in open revolt against the metropole. The US debated interfering in the conflict and decided to send the USS Main to Havana as a show of resolve. The Main exploded mysteriously, perhaps an engineering disaster, but it was blamed on Spain and became a casus belli. The Spanish American War was won quickly by the United States. The outcome was that Cuba received independence, and the US gained sovereignty over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippine Islands.

The US also received the insurgency movements underway in Spain’s former territories. Believing that the US would give independence to the Philippines, Filipino nationalists were soon disappointed. The conflict that followed, the Philippine–American War, is almost unknown in the continental US and never taught in schools. The war resulted in at least 200,000 civilian deaths, and as all Filipinos were US nationals, this was the worst war for non-combatants in US history. In the end, the US prevailed over its colony. Immerwahr describes how the American colonial administration brought architecture and city planning, educational standards, particularly in nursing, and military basing to the islands, but not American style democracy. That was reserved for the homeland.

Part of the United States’ contemporary hegemony is in global standardization. Starting in WWII and continuing in the reconstruction that followed, the US established global standards for engineering, logistics, communications, and materials. Necessitated by the war effort, these standards were required by any nation participating in manufacturing for the US defense establishment, a massive market that established logistical bases globally. The drive to standardize continued in the reconstruction after the war and was the precondition that led to today’s global markets.

English, too, became part of this standardization. A global market required a lingua franca to facilitate it. In the post-colonial era, many states pushed national languages; some went so far as to ban English from the classroom. However, as Immerwahr writes: “For those who speak English as a foreign language, the reasons are clear. English is the language of power. Speaking it means going to better schools, getting better jobs, and moving in more elite circles. A study commissioned by the British Council of five poorer countries (Pakistan, Bangladesh, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Rwanda) found that professionals who spoke English earned 20 to 30 percent more than those who didn’t” (p. 334). English has become the most common “second language” spoken globally. “If the Chinese…rule the world someday,” the linguist John McWhorter has written, “I suspect they will do it in English” (p. 333).

How to Hide an Empire is an important and relevant book strongly recommended for foreign policy decision makers as well as armchair historians. There is a nascent but growing literature not on specific empires but empire in general: categories of empire, and analysis of the different ways they form, how they sustain themselves, and why they fall. Immerwahr adds to this conversation while at the same time provides a clear picture of US imperial history, and paints a detailed and more attractive future for the United States’ hidden pointillist empire than its complicated and often ugly colonial past.