Strategic Assessment

The involvement of Chinese companies in national infrastructure tenders in Israel has sparked concern in recent years among Israeli and United States government figures. This paper examines the involvement of Chinese companies in various infrastructure tenders in Israel in comparison to other foreign involvement, broken down by category and arranged chronologically, and finds that the high Chinese participation in tenders reflects primarily a lack of interest in these tenders by other countries. Moreover, Chinese companies have won primarily construction tenders for infrastructure, and fewer operations tenders. These companies won a particularly high number of tenders in 2015 and 2019, but since the establishment in 2020 of the Advisory Board for Evaluating National Security Aspects of Foreign Investments in Israel, they have ceased winning bids for operations.

Introduction

Chinese companies have constructed and operated national infrastructure in Israel since 2006, but this involvement is a matter of controversy. Supporters, including Finance Ministry officials, claim that Chinese companies can construct necessary infrastructure rapidly and efficiently, and that their very participation in tenders lowers all bids, such that even if they are not awarded the specific contract they save public funds. Security elements, however, have raised concerns about risks entailed in Chinese involvement in national infrastructure. For example, former head of the Israel Security Agency Nadav Argaman claimed in January 2019 that “Chinese involvement in Israel is especially dangerous for everything related to strategic infrastructure and large companies in our economy.” He made this statement while the Advisory Board for Evaluating National Security Aspects of Foreign Investments was in formation in Jerusalem, in light of repeated warnings by Trump administration officials of the risks of Chinese investments in Israel, including risks of espionage, capacity to shut down infrastructure, and leverage over the Israeli government. While Washington was primarily concerned about technology investments in Israel, infrastructure investments are public knowledge and thus easier to monitor. In addition to security concerns, the Israel Builders Association (IBA) claims that all the Chinese companies operating in Israel are a single “holding group” owned by the Chinese government, which thereby takes over the infrastructure market in Israel. The High Court of Justice rejected this claim, but according to the IBA, “The Chinese government competes unfairly in the infrastructure market and endangers hundreds of Israeli companies, which employ tens of thousands of workers.”

An additional and particularly serious concern is the potential harm to Israel’s special relations with the United States. The establishment of the Advisory Board did not satisfy the Trump administration, and the strategic competition between the superpowers has not diminished with the change of administration in Washington. The Biden administration may use different means and its senior officials may communicate with politer and more articulate language, but let there be no mistake—the strategic perspective that views China as a rival threatening the global order and the leading United States role remains. Continued Chinese involvement in national infrastructure tenders will thus certainly increase tension between Israel and its closest friend. It is thus particularly important to understand Chinese involvement in Israeli national infrastructure. This article gives an up-to-date picture of this involvement, analyzes its characteristics, and proposes relevant policy recommendations.

Methodology

In the absence of a government database documenting infrastructure tenders in various fields, information about infrastructure tenders was culled from the websites of Israeli government corporations NTA Metropolitan Mass Transit System Ltd., Netivei Israel National Transport Infrastructure Ltd., Israel Port Company, Israel Electric Corporation, the Water Authority, and Israel Railways; Chinese company websites; Knesset reports; and publications in the Israeli and foreign press. On this basis an initial database was created. Of 72 tenders in the database, 46 from the period of 2001-June 2022 were selected that amounted to NIS 100 million or more and dealt with ports infrastructure; intercity rail; Tel Aviv area metro and light rail, including provision of engines and railway cars; power stations; desalination plants; and road paving. The database excludes tenders that were closed to foreign companies and tenders that were not for national infrastructure. For each tender, the database lists the type of infrastructure, purpose of the project, the companies competing in the final stage, the winning companies, and the closing date of the tender. The tally is by tender and not by company, so that in instances where a number of companies from the same country competed or won a tender together, they were counted only once.

Security elements have raised concerns about risks entailed in Chinese involvement in national infrastructure. For example, former head of the Israel Security Agency Nadav Argaman claimed in January 2019 that “Chinese involvement in Israel is especially dangerous for everything related to strategic infrastructure and large companies in our economy.”

One of the limitations of the research results from the incomplete information available. Official sources do not name all bidders for each tender but rather only the winning bidder. The press also sometimes names only the winning bid and does not describe the full tender process, and as a result, information about participants in various stages of the tenders is incomplete. To circumvent this limitation, the present work focuses on the final stage of tenders and the winning bidders.

Foreign Involvement in Israel’s National Infrastructure

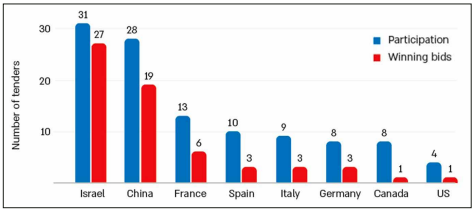

Figure 1: Participation and winning bids, by country

Companies from 17 foreign countries joined Israel to participate in infrastructure tenders, with China, France, Spain, Italy, German, Canada, and the United States having won the greatest number of tenders (Figure 1). The complexity of the projects requires companies to associate into groups. Thus, for example, in order to bid for the tender for management of the Tel Aviv area metro, companies from Israel, France, and Canada formed a group; in another group companies from Israel, France, and Italy submitted a joint bid. Thus, in a single tender, companies from the same country competed against one another.

Likewise, sometimes two companies joined together for the purposes of bidding on one tender but competed against one another on a different tender. For example, the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) made a joint bid with the Israel firm Minrav Engineeering, and in a different tender the two companies competed against one another. This complexity makes it difficult to analyze results by country of bidder, but the breakdown results shown in Figure 1 show clearly that Chinese companies bid and won more tenders than other foreign companies. Chinese companies participated in 61 percent of all tenders (28 of 46), in comparison to French companies, who had the second-highest rate of participation at 28 percent. Companies from the United States were in seventh place among foreign companies, participating in only 8.7 percent of tenders.

The breakdown of winning bids also demonstrates the dominance of Chinese companies, although it is less pronounced. Chinese companies won 68 percent of the tenders for which they bid, versus 46 percent for French companies and 25 percent for American companies. Chinese companies won fewer tenders than Israeli companies, who won 84 percent of the tenders for which they bid, although in most tenders, bidding groups included both Israeli and Chinese companies.

Chinese Involvement in Israel’s National Infrastructure

Chinese involvement in Israeli ports and in the Tel Aviv light rail is well-known and has been covered extensively by the Israeli press. Some connect it to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI—see also Mordechai Chaziza’s article in this issue), announced by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013. The BRI is a strategic program to develop land and maritime trade routes from China, the world’s largest exporter, via central Asian and Middle East countries that are in need of new infrastructure, to markets in prosperous European states and to African countries that supply China with important raw materials. With this Initiative China seeks to diversify its trade routes, take advantage of excess capacity among Chinese infrastructure companies, strengthen its ties and its influence with countries along the way, and present itself as a responsible power engaged in global development. Even before the BRI was announced, Chinese companies were involved in various infrastructure initiatives around the world, including in Israel, but the BRI provided the conceptual framework and brought Chinese government financial and diplomatic support into the picture.

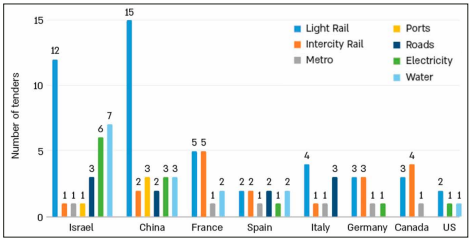

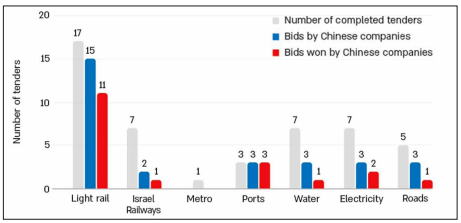

Figure 2: Participation in tenders (final stage), by sector

It appears that the involvement of Chinese companies in Israel is not directly connected to the BRI, and goes beyond the transportation sector to other types of infrastructure. Chinese (as well as Spanish) companies participated in tenders in six of the seven sectors that were examined, as opposed to companies from other countries that focused on fewer sectors (Figure 2). Chinese companies participated in light rail and port tenders, as well as in electricity and water tenders. On the other hand, their participation in intercity rail tenders was quite limited.

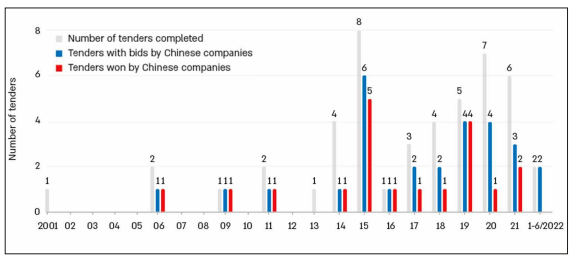

Figure 3: Breakdown of tenders by year

Figure 3 illustrates Chinese companies’ participation in tenders chronologically. Chinese companies typically won one bid a year, independent of the number of tenders completed that year. For example, four tenders and one tender were completed in 2014 and 2016, respectively, but in both years Chinese companies competed in one tender and won it.

In certain years the pattern diverged. In 2015 a record eight tenders were completed, half of which were tenders for the Red Line of the Tel Aviv light rail. Chinese companies won five of the six tenders on which they bid, or 83 percent. In spite of the temptation to explain this expansion of Chinese companies outside of China by the BRI, it is better explained by a specific event. In July 2012, then-Transportation Minister Israel Katz visited China and signed a cooperation agreement between the two countries in the fields of transportation and infrastructure. In 2013 then-Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu also visited China and met with the president of the Chinese Development Bank (CDB), which provides loans for infrastructure initiatives both within and outside China. These visits and agreements also influenced Israeli government decisions, leading to the high rates of Chinese companies winning the tenders on which they bid.

2019 too departed from the more familiar pattern. Five tenders were completed, and Chinese companies won all four of the tenders on which they bid, i.e., 100 percent. This increase is surprising for two reasons. First, it conflicted with restrictions imposed by the Chinese government in mid-2018 on sending capital outside the country’s borders, which aimed to reduce risks to the local Chinese economy. These limitations led to a reduction in Chinese investments worldwide as well as in Israel; hence the unexpected increased involvement in Israeli infrastructure. Second, from mid-2018, the Israeli government was pressured publicly by the Trump administration and other parties about reducing Chinese infrastructure investments. They opposed the Haifa Port tender, for example, which was won by the Shanghai International Port Group (SIPG) in 2015. In that case, the high rate of Chinese companies winning tenders in 2019, including a tender for purchasing and operating the Alon Tavor power station, indicates that the Israeli government at that time continued with a policy of encouraging investment by Chinese companies, in spite of the changed policy and pressure from Washington.

2020 was a turning point for the patterns of Chinese companies winning bids; seven tenders were completed, and Chinese companies won only one bid of the four they submitted. In 2021 Chinese companies won two bids of the three they submitted, but the rate of winning did not compare to its 2019 peak and decreased to 66 percent.

The breakdown of tenders won by Chinese companies over the last few years clearly reflects American influence over decision makers in Israel on national infrastructure initiatives.

The decline in Chinese winning tenders can be attributed to the Advisory Board for Evaluating National Security Aspects of Foreign Investments, which began to function in 2020. While this board is a voluntary mechanism for regulators and its decisions are ostensibly non-binding, in practice its discussions and messages reverberate in the press, and in turn create a constraining effect. This effect is felt by the Israeli regulators, who think twice about authorizing bids by Chinese companies; by the Chinese companies, which reexamine the advisability of participating in these tenders; and by Israeli and foreign companies, which may reconsider the effect of cooperating with a Chinese company on their chance of winning. The COVID-19 pandemic may have had a certain impact on Chinese companies’ participation in Israeli infrastructure tenders, but due to the length of time between the publication of tenders and their completion, this cannot yet be evaluated. In the first half of 2022 Chinese companies did not win either of the two tenders that were issued and on which they bid.

In this situation, the breakdown of tenders won by Chinese companies over the last few years clearly reflects American influence over decision makers in Israel on national infrastructure initiatives. After reaching a peak in 2019, 2020 stood out as a low point for Chinese companies winning tenders, in which they only won 25 percent of the tenders on which they bid. This was the year in which the tenders for the Ramat Hovav power station and the Sorek B desalination plant were completed, which generated public interest and were apparently discussed during the visit by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to Israel. The Chinese companies that bid on these tenders did not win them.

The three tenders won by Chinese companies since 2019 were all small-scale tenders for infrastructure construction. In 2020 a Chinese company won the tender for building the Rokach bridge, and in 2021 Chinese companies won two tenders—one for building a bridge and the Pinchas Rosen light rail station, and the other for initial infrastructure work around Rabin Square.

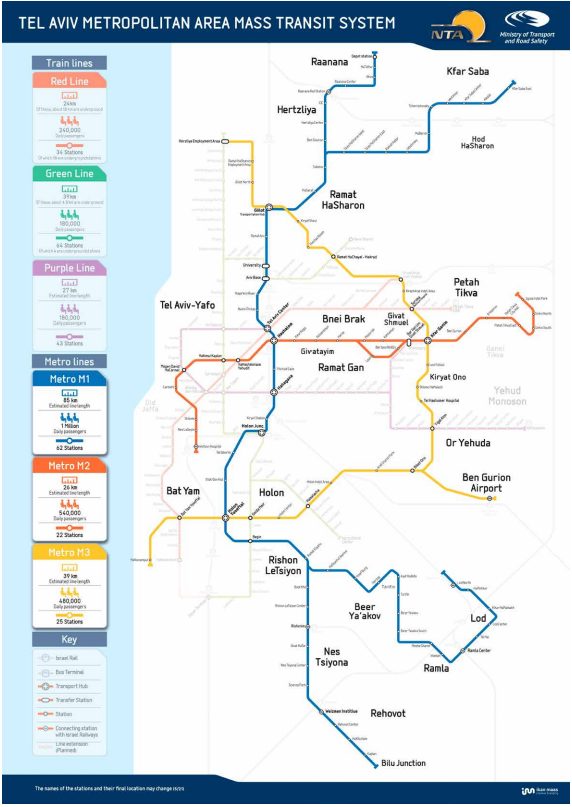

Figure 4: Mass transit system in metropolitan Tel Aviv | Source: NTA, Metro Lines (updated as of 4/2021). Final station names and locations may change.

The light rail in Tel Aviv comprises the Red Line (most central), the Green Line, and the Purple Line (Figure 4). The Red Line spans 24 km, half of which are in underground tunnels, and includes 34 stations, of which ten are underground. This enormous project has already been built and is expected to begin operating regularly in late 2022, but its construction entailed many difficulties and delays. The first tender was decided back in 2006, but funding issues in the winning group, which included CCECC, led to its nationalization in 2010. The construction of the Green Line also entailed substantial delays, and work on it only commenced in mid-2020, along with the Purple Line.

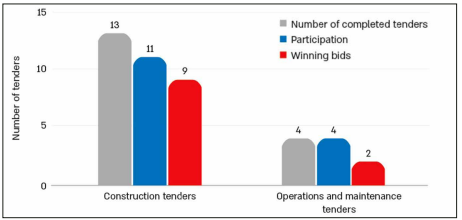

The construction of all lines is under the responsibility of the government company NTA (Metropolitan Mass Transit System Ltd.), which supervises the entire project and publishes two types of tenders: construction tenders and operations tenders. The group that wins a construction tender functions as a contractor, which works for a limited time and receives payment for this work from the government. The risks in infrastructure initiatives of this type do not include dependence or the ability of an external actor to shut down a system, and therefore in the context of non-sensitive infrastructure, the risk level is low. In contrast, the group that wins an operations tender wins a long-term contract for managing infrastructure and profits from its operation. Such infrastructure initiatives are exposed to all risks, and particularly the risks of dependence or shut-down capabilities. In initiatives of this type the foreign firm also uses local companies as subcontractors, which reduces some of the risk, especially the classic security risk of espionage. In the period reviewed here, NTA issued 17 tenders, of which 13 were for construction and four were for operation of the three lines.

Figure 5: Bids by Chinese companies for Tel Aviv light rail tenders

Chinese companies won primarily construction tenders, nominally and proportionally (Figure 5). Their rate of winning these tenders is 82 percent, or nine of eleven tenders on which they bid. On the other hand, their rate of winning operations tenders is only 50 percent, or two of four tenders. The first such tender, for the operation of the Red Line, was won by the Tevel group, comprising the Israeli company Egged and the Chinese companies Shenzhen Metro and CCECC. The second such tender was for supplying 90 train cars for the Red Line and maintaining them for 16 years. The two winning operations tenders that included no Chinese company were the tenders for the Green Line, which were decided in 2022. In one case, one of these groups went to court with the claim that its non-winning was tainted by political considerations and stemmed from US pressure on the Israeli government.

It is possible that a lower rate of Chinese firms winning operations tenders led them to refrain from bidding on the only tender issued in 2021, for operating the metro network in the Tel Aviv metropolitan region.

Additional Transportation Tenders

In contrast to the extensive involvement of Chinese firms in ports and Tel Aviv light rail tenders, there has been less participation in tenders related to intercity rail activity. Of seven such tenders, Chinese companies bid on only two—digging the Mt. Gilon tunnel on the Karmiel-Acre rail line, and supplying engines—and won only the former tender. Chinese companies chose not to bid on the other tenders, in spite of these requiring the exact capabilities they possess, such as track laying, maintenance and upgrades of train cars, train tracks electrification, and signal system upgrades. This may be due to these tenders including requirements that prevent Chinese participation. For example, in the tender that ended in 2017 for providing 330 rail cars, Israel Railways changed the specifications from what had been standard until then, and included a requirement to lower platforms in accordance with the European standard—a capability that most Chinese companies do not have.

Tenders involving Chinese companies that attracted much attention were tenders for Israeli ports. Chinese companies participated and won in all three of these tenders: Pan-Mediterranean Engineering Company (PMEC) won the tenders for constructing the Southport Terminal in Ashdod and upgrading and deepening platform 21 in the Ashdod port. SIPG won the tender for operating the Bayport Terminal in Haifa, which is still mentioned as one of the security risks involved in Chinese infrastructure investments. The heated press coverage of this subject perhaps encouraged the outcome whereby no Chinese company bid on the tender to privatize the Haifa port, which was issued in 2020.

In four tenders for paving roads, Chinese companies won one tender of the two on which they bid—building the Olga Interchange on Highway 2.

Tenders in Energy

A total of 14 tenders were issued in the fields of electricity and water over the last two decades, of which six were between 2019-2021; this may explain a portion of the overall rise in tenders issued during these years. Chinese companies won three out of the six tenders on which they bid: constructing the Sorek A desalination plant; purchasing the Alon Tavor power station; and operating a hydroelectric power station at Kochav Hayarden. The winning bid for the Alon Tavor power station was as part of the MRC group, which included the Israeli firms Mivtach Shamir and Rapac Energy and PMEC. The latter, in accordance with the requirements of the National Security Council, does not hold a controlling interest in the winning corporation and was denied veto rights in decisions. PMEC is the branch in Israel of China Harbor Engineering Company (CHEC), which is itself a subsidiary of the China Communications Construction Company Ltd (CCCC). The structure of this complex company indicates one of the advantages and disadvantages of Chinese companies. The advantage is that they are part of an enormous system of companies with extensive experience and knowledge in a variety of fields. This advantage may become a disadvantage when one of the parent companies meets with difficulty. In the case of PMEC, CCCC, the parent company was added to a United States blacklist in August 2020 for carrying out work that aids the Communist Party in securing its hold in the South China Sea. This fact overshadowed PMEC’s participation in the tender for purchasing the Ramat Hovav power station, which it ultimately did not win.

It is notable that Chinese companies did not show interest in the four tenders issued for establishing solar power stations, but did participate in and won a bid for establishing and operating the green power station at Kochav Hayarden, which is operated via pumped storage hydroelectricity. Hydroelectric power explains the interest of Chinese firm Hutchison Water from Hong Kong in this tender. The same company also won the tender for operating the Sorek A desalination plant, as part of a group that includes the Israeli companies IDE and SDL Technologies. In contrast, it bid on a tender to operate the Sorek B desalination plant in 2020 and did not win. That was after PMEC was already disqualified due to “lack of experience.”

Figure 6: Bids on tenders by Chinese companies, by type of infrastructure

In the distribution of bids won by Chinese companies in tenders for all types of infrastructure (Figure 6), Chinese companies bid on 28 tenders (61 percent of the total) and won 19 bids (68 percent of the tenders on which they bid). Of these, 13 were tenders for construction and six were tenders for operations: two for ports (66 percent), two for power stations (around 28.5 percent), one for water facilities (around 14 percent) and one for the Tel Aviv light rail (around 6.6 percent).

Conclusion

This work examined the involvement of Chinese companies in national infrastructure in Israel in comparison to companies from other nations, broken down according to type of infrastructure and arranged chronologically.

The findings show that Chinese companies competed in a greater number and wider variety of tenders on infrastructure types than companies from other foreign countries. Perhaps predictably, then, the number of tenders won by Chinese companies significantly exceeded the number of tenders won by other foreign companies. Chinese companies do not necessarily win infrastructure tenders due to preferential treatment by Israel, but rather due to fewer foreign competitors. An extreme example of this is the tender for operating Haifa's Bayport Terminal, where SIPG was the sole bidder. Likewise, for many of the Tel Aviv light rail tenders, Chinese companies were part of all the groups that submitted bids. In such a case there is no choice but to allow a Chinese company to win, as part of a group. Furthermore, given that companies from other foreign countries do not participate in tenders for all types of infrastructure, the absence of Chinese companies sometimes means that only Israeli companies participate. The implications include lack of knowledge and experience in certain fields, and a lower level of competitiveness, lack of diversity, high costs, and—in the case of infrastructure operations—a return to the era of powerful workers unions, like the port and rail workers unions.

Chinese involvement in infrastructure has clear advantages for Israel, but at the same time exposure to various risks should be minimized, and China-US relations—which are not expected to improve in the foreseeable future—must be taken into account.

In 2015 the number of successful bids by Chinese companies for infrastructure tenders in Israel increased, apparently as a result of tightened relations following visits to China by the Prime Minister and the Minister of Transportation. A second increase was noted in 2019 and reflects continued policy of the Israeli government of encouraging participation by Chinese companies in spite of adamant messages from Washington opposing Chinese involvement in investments and infrastructure. 2020 was a low point for Chinese companies winning bids, and although in 2021 this trend was reversed, this was in relatively small tenders. The downturn in winning bids in 2020 can be attributed to the Advisory Board for Evaluating National Security Aspects of Foreign Investments, which began its work on January 1, 2020. Even though it does not discuss all tenders, its very existence has a chilling effect on various actors. The Board’s influence is particularly clear in infrastructure operations tenders, as 2019 was the last year in which a Chinese company won any tender for infrastructure operations (the Alon Tavor power station)—despite Chinese companies competing in five operations tenders since the beginning of 2020.

Chinese involvement in infrastructure has clear advantages for Israel, but at the same time exposure to various risks should be minimized, and China-US relations—which are not expected to improve in the foreseeable future—must be taken into account. Accordingly, the following actions are recommended for relevant Israeli government policymakers.

First, the Advisory Board must have a broad picture of the involvement of all companies from a given country in the State of Israel in order to make decisions about the involvement of a certain foreign company in a national infrastructure project, and prevent foreign government control over such infrastructure. A governmental database should thus be established with data on tenders for all types of infrastructure, and should be updated regularly. Such a database would provide a comprehensive picture of foreign company involvement in national infrastructure tenders, and allow identification of trends and changes over time.

Second, Israel has thus far chosen—wisely—to limit the risks inherent in foreign investments in infrastructure in different ways, such as in the electricity reform that mandated that network management and electricity provision remain in the hands of the state, with foreign companies limited to manufacturing up to a certain amount of electricity in order to prevent excess concentration and dependence. Similarly, the ports reform left the state in charge of management, maintenance, and development of the ports, and allowed renting them to foreign operation companies. It is thus recommended that Israel formulate similar procedures for the fields of electricity, water, and transportation. This will allow foreign involvement in construction tenders with lower security risks, but will limit foreign company involvement and prevent excessive control in operating critical infrastructure. It will thus be necessary to determine the maximum foreign involvement acceptable for each type of infrastructure.

Third, in addition to the authority to review proposed investments, the Advisory Board must engage with Israeli companies to convey government requirements for cooperation with foreign companies and allow Israeli companies to adapt themselves. These actions will enable Israel to reduce the risks of exposing its national infrastructure to the investment of foreign companies, while at the same time enjoying the advantages that such investments offers.