Publications

INSS Insight No. 1817, January 21, 2024

Since the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7 and the ensuing war in Gaza, there has been very little security-related news coming out of East Jerusalem. This is in stark contrast to the growing security challenges in the West Bank and to previous campaigns involving Israel and Hamas, in which there were clashes between Israeli forces and Palestinians not only on the streets of East Jerusalem and at the al-Aqsa Mosque, but also in Israeli cities such as Acre and Bat Yam. This article offers reasons that may explain this discrepancy. In addition, it suggests what we can expect to see emanating from East Jerusalem in the reality of the current war, and considers some of the policy options available to Israel.

East Jerusalem, Prior to October 7

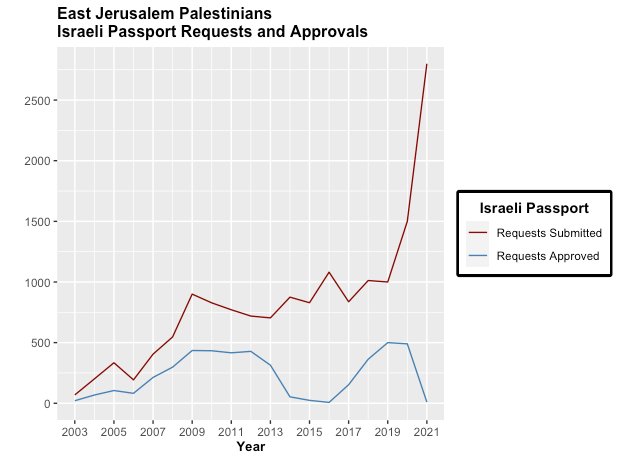

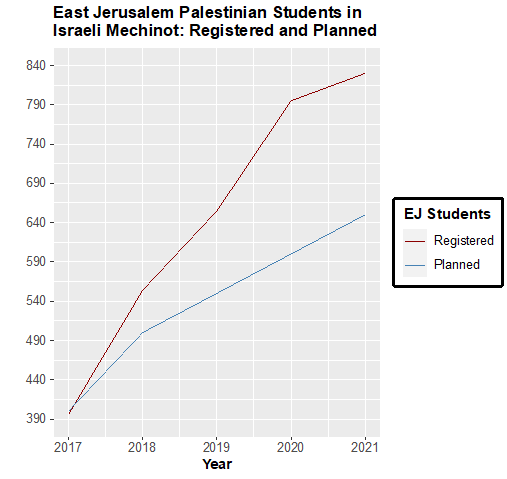

To suggest that there was no incitement, violence, or terrorism perpetrated against Israelis from East Jerusalem in the years prior to October 7 is incorrect. For example, from 2015-2022, Jerusalem experienced approximately fourteen terror attacks each year. At the same time, in the years before October 7 there were empirical trends from multiple sources that suggested less hostile attitudes by East Jerusalem Palestinians toward Israel. These initial trends from sources across the political spectrum were largely consistent, notwithstanding largely right wing governments during this period. First, a Special East Jerusalem Poll conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR) in November 2022 among 1,000 East Jerusalem Palestinians demonstrated an increased demand for Israeli citizenship by 13 percentage points over 2010–2022. Second, a poll conducted by David Pollock from the Washington Institute among 300 East Jerusalem Palestinians on June 6–21, 2022 showed that 48 percent of the city’s Palestinian residents said that if they had to choose, they would prefer to become citizens of Israel rather than a Palestinian state. In contrast, from 2017-2020, that same figure hovered around just 20 percent. This same poll also showed a preference among East Jerusalem Palestinians to “focus on practical matters” (62 percent) and “counter Islamic extremism” (62 percent). These trends were further corroborated by raw data demonstrating not only a jump in the number of applications for Israeli passports among East Jerusalem Palestinians (Figure 1), but also an increase in the number of East Jerusalem Palestinian students registered in Israeli university preparatory programs, significantly more than anticipated (Figure 2).

Figure 1:

Sources: N. Hasson, “All the Ways East Jerusalem Palestinians Get Rejected in Bid to Become Israelis,” Haaretz, January 15, 2019; N. Hasson, “Just 5 Percent of E. Jerusalem Palestinians Have Received Israeli Citizenship Since 1967,” Haaretz, May 29, 2022.

Figure 2:

Sources: A.Yazri, Summary of Government Decision 3790,” Misrad Yerushalim, May 2023 [Hebrew]; D. Levi, “First Generation of Higher Education in Israel: Integration Processes of East Jerusalem Youth in Israeli Academia,” Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research (2023) [Hebrew].

East Jerusalem, Since October 7

Both conventional wisdom and empirical data would suggest that Israel’s response in Gaza to the Hamas attack on October 7, in addition to heighted security measures in East Jerusalem against Palestinians there, would reverse these trends and incite more violence and anger against Israelis. This was the reaction from East Jerusalem Palestinians in 2014 with Operation Protective Edge, in 2015 with increased tension in the city surrounding Jewish visits to the Temple Mount, and in 2017 with the closing of al-Aqsa because of a terrorist attack there. According to a recent public opinion poll by PCPSR of November 22- December 2, 2023, it i also reflects the stance of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, with support for Hamas more than triple the rate of three months ago, and support for armed struggle rising ten percentage points, with 60 percent saying “it is the best means for ending the Israeli occupation.” Notably, and according to the same poll from PCPSR, in the West Bank more broadly, this percentage rises closer to 70 percent. Data focusing specifically on East Jerusalem and public opinion among the Palestinian population there have not yet been released; however, Hamas has been pursuing a strategy of widespread Palestinian consolidation across Gaza, Israel, Jerusalem, and the West Bank.

Nonetheless, at least on the ground, East Jerusalem appears to be largely bucking the trend. That is not to say that there have not been sporadic terrorist attacks against Israelis emanating from East Jerusalem – indeed, there have been several documented attacks, with the November 30 shooting at a bus stop in the city perhaps the most notable. There have, however, essentially been no large-scale clashes or large violent protests.

Why the “Quiet” In East Jerusalem Since October 7?

There are at least four reasons that might explain why East Jerusalem has been relatively quiet since October 7. First, Israel has heightened its security presence in East Jerusalem. While here have been some claims of excessive brutality and unwarranted arrests, it is almost certain that this greater security presence has thwarted terrorist attacks.

Second, during the war in Gaza and with the increase in clashes between Israel and Hezbollah on the northern border, East Jerusalem simply is a less attractive item on the media’s list. This does not mean that nothing is happening there. For example, there are still more minor clashes every Friday in Wadi Joz because of Israel’s decision to close al-Aqsa to young Palestinians. And there are still strikes, home demolitions, and quite a bit of violence.

Third, East Jerusalem Palestinians are possibly confused – quite similar to the Arab citizens of Israel, about how to digest and respond to the Hamas's horrific events of October 7. While they likely condemn Israel’s war on Gaza, they are also often more able to recognize the utter inhumanity of the deeds of Hamas on October 7 than Palestinians in Gaza or the West Bank. But any expression of understanding or empathy by them for Israelis, or condemnation of Hamas, would be perceived among their community as an abandonment of their identification with the national cause. As such, many likely choose to remain silent.

Finally, and most important, Jerusalem in the truest sense is a mixed city. Many East Jerusalem Palestinians are highly enmeshed in the fabric of the city, working and studying in the city's businesses, schools, and universities. Many are interested in advancing their own interests and those of their families and recognize that any incitement – especially during this time of extreme tension and fear – has the potential to completely destroy their lives. As such, they choose to remain largely silent. And with more frontal expressions of anger, frustration, or violence since October 7 largely muted, East Jerusalem has witnessed a form of “community awakening” characterized by increased community activities and volunteering.

What Presumably Lies Ahead?

Largely because so many East Jerusalem Palestinians’ lives are so intertwined with the Western part of the city, a large scale national uprising from East Jerusalem is unlikely. This expectation is buttressed by a warming of East Jerusalem Palestinians toward Israel in recent years, and what are likely their dilemmas regarding how to respond to the events of October 7.

This does not mean that that we will not continue to see smaller, lone-wolf terrorist attacks against Israelis in and from East Jerusalem. The pictures and videos coming out of Gaza are undoubtedly very hard to digest. As we have seen on more than one occasion since October 7, we can expect that youth from East Jerusalem will be motivated and convinced to engage in terror attacks against Israelis.

Under these circumstances, and largely in light of the terror attacks that might emanate from East Jerusalem, Israel should maintain a strong security presence and robust intelligence surveillance there. Eruption of widespread violent clashes, particularly in and around al-Aqsa, would introduce a new ominous dimension to the war and might further encourage disruptions among Arab citizens in Israel, as well as in other Arab countries.

In the long term, however, notwithstanding the present war, continued restraint in Jerusalem will prove that the city is a “mixed” one in the truest sense. This is a reality from which neither Palestinians nor Israelis in the city will be able to escape. As a result, when the war ends and tension dissipates, long term Israeli policy must be aimed toward creating a more viable future for Palestinians in East Jerusalem and Israelis in West Jerusalem alike. Investing in projects like Plan 3790, which has a stated goal of reducing socio-economic gaps and promoting economic development in East Jerusalem, and others like it, as opposed to mostly focusing on security, will ensure the development of a sustainable city that will remain part Israeli and part Palestinian.