Publications

Special Publication, August 29, 2022

The establishment of diplomatic relations between Israel and China in 1992 did not prompt Israeli universities to change the classic course of their research, and new studies on China were not among their priorities. Despite this trend, Prof. Aron Shai, one of Israel’s veteran Sinologists, dedicated many books to the subject, including China and Israel: Chinese, Jews; Beijing, Jerusalem. As the founder of the East Asian Studies Department at Tel Aviv University, Prof. Shai was asked about his insights on Israel-China ties and the development of knowledge about China in institutions of higher education in Israel. Prof. Shai looks positively at the revolution in Israel-China relations in the past 30 years, but advises that these relations be conducted judiciously and with awareness of Israel’s historic and strategic relations with the United States.

Prof. Aron Shai's interest in China, the vast nation in the east, began when he was a young socialist in Israel in the 1960s. He saw a possible way of managing a country using certain elements of the Chinese model, which was based on theories and ideologies, Marxism-Leninism in particular. At the same time, with a flexible outlook, he proposed adjustments for countries interested in applying the Chinese example, with the help of "Mao Zedong Thought," for instance. Shai saw additional parallels between China and Israel in the "pioneering empathy" that the two countries demonstrated in Africa. He contends that when the continent was freed from the burden of colonialism, both China and Israel supplied it with friendly and non-patronizing external aid – resources without loans and activity on the ground, rather than from a distance.

In addition to his interest in China from governmental theories, Shai was greatly interested in the relations between China and the Jews – a subject that he asserts has not yet been researched fully and should be the subject of further study. For example, additional research should be concentrated on the asylum provided to persecuted Jews from Europe, especially in Shanghai. Credit for this is usually given to the Chinese authorities, but knowledge of the local situation at the relevant time is likely to show that the credit in fact belongs to the Japanese authorities. Shai states that as occupiers, the Japanese held sway over large parts of eastern China and cities where Jews found refuge.

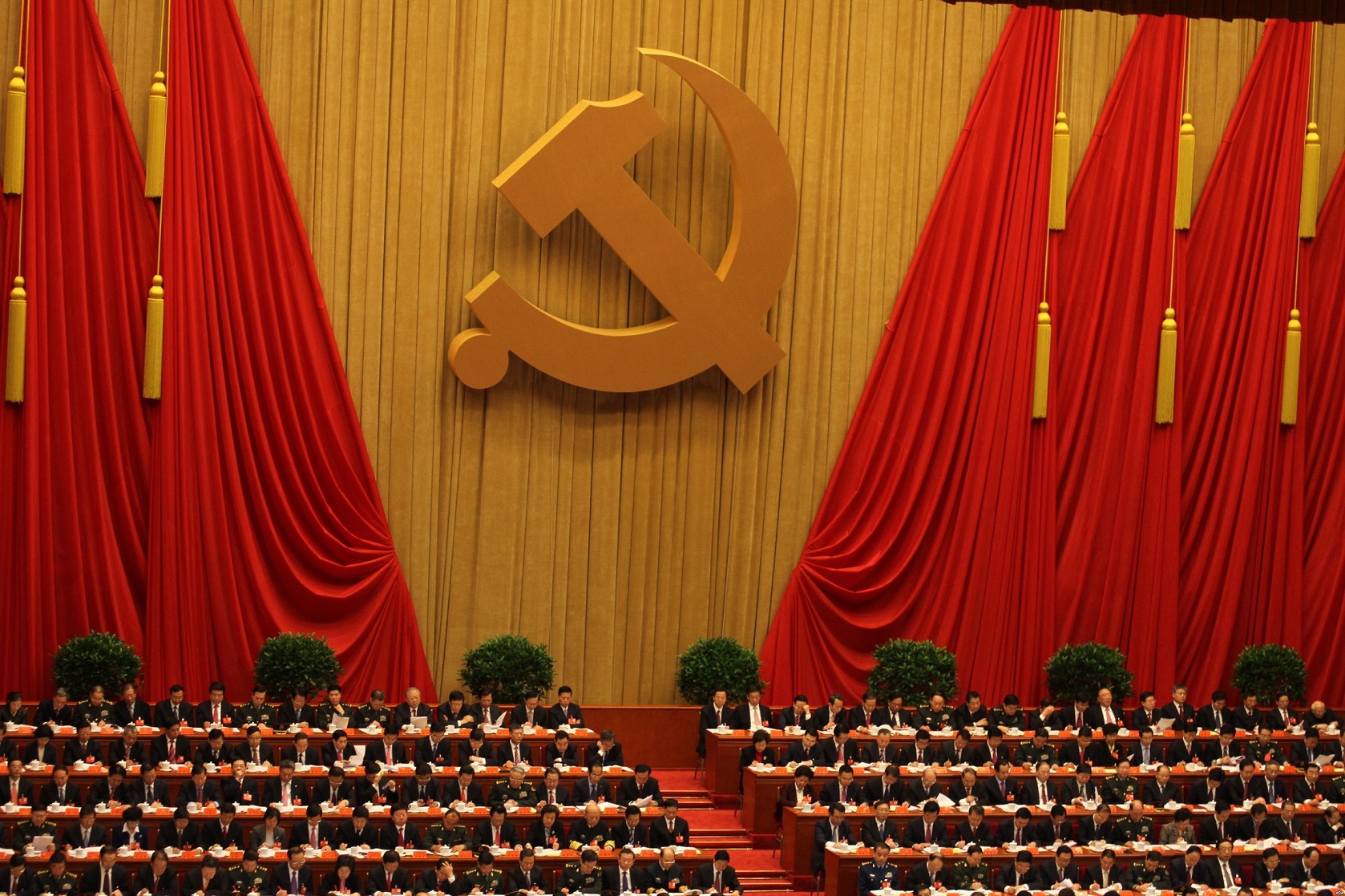

Subjects addressed in Shai's wide-ranging research include the origins of World War II in Asia (the Sino-Japanese war); the West's withdrawal from East Asia upon the rise of nationalism in China, India, and Southeast Asia; and the fate of foreign companies in China following the establishment of the Communist regime there. Shai argues that the Chinese wanted to have their cake and eat it, too: on the one hand, they wanted to benefit from the foreign companies' spheres of activity with which they were insufficiently familiar, such as urban transportation and chemical industries. On the other hand, they sought to act independently. They used sophisticated methods to gain control of foreign companies but did not allow foreign managers to leave China. These managers were supposed to serve as mentors to the Chinese managers and workers who succeeded them. According to Shai, the Chinese usually gained the upper hand in negotiation processes and commercial confrontations, and thus companies left quite a bit of their assets behind. Today, it is an astonishing fact to Shai that dozens of foreign companies, among them Siemens, the Spanish company Telefonica, H&M, Volkswagen, Peugeot, and ThyssenKrupp acceded, or even surrendered, to the Chinese government's demands in order to continue benefiting from their activity there. Furthermore, he adds, that while these companies sympathize indirectly with the criticism regarding the human rights situation in China, at the same time they continue their involvement in economic activity in the Xinjiang region.

Prof. Shai examined and analyzed the fate of several Israeli companies that operated in China, and explained the reasons for their losses. He found that while the diplomatic relations between Israel and China, which were forged in 1992, kept improving, many of the Israeli businesses that tried to do business with China failed completely, because Israeli businesspeople saw, and still see, the Chinese market as a great opportunity for a quick and easy profit, but their vision is short term. They do not learn enough about the Chinese market, Chinese culture, local perceptions, and the risks incurred in this context. As a result, they arrive in China with very limited knowledge and fail because of their lack of understanding of the Chinese mind and how it works.

Recently, following the severe restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic and unfavorable governmental changes in China, there has been, according to Shai, a gradual withdrawal from China by companies and their managers. Even the Israeli community living in China has shrunk. Nevertheless, bilateral trade between Israel and China continues as before, and in general remains unbalanced: Israeli exports to China consistently amount to less than a third of total bilateral trade. A few hi-tech companies, such as Intel, account for most of Israel's exports to China. In services, where Israel excels, there is no breakthrough on the horizon.

Shai, the founder of the East Asian Studies Department at Tel Aviv University, was asked about the academic ties between Israel and China. As a young scholar in the 1970s, Shai found higher education in Israel to be very Eurocentric, and sound academic research on China was lacking. The heads of Tel Aviv University initially rejected his idea when he tried to convince them of the need for a special department on this subject, especially since the Hebrew University of Jerusalem was already launching such a department. In 1995, however, it was nevertheless decided to establish an East Asian Studies Department at Tel Aviv University. Some believed that this department would be unable to maintain itself, but it was a spectacular success, and very quickly became the University's largest department, with over 700 students. The department's success also helped introduce the study of Chinese language and history in high schools, including the development of matriculation exams in these subjects.

The Chinese government saw the founding of the department at Tel Aviv University as having potential for the establishment of a Confucius Institute – something that did not yet exist in Israel. As the East Asian Studies Department head, Shai received a query on this matter. However, he refused to sign the contract in the format proposed by the Chinese and demanded some balancing changes to delineate the boundaries between the new Institute and the University. Under the agreed terms, the Confucius Institute was designed to promote the study of the Chinese language among the general public, but language studies in the academic framework were to run solely according to academic criteria, with the department's own teachers and books, different than those of the Institute. Shai says that this constraint and others have prevented the Confucius Institute from influencing the department's academic studies and research.

The existence of the Confucius Institute at the university required alertness and delicate management in a number of events. For example, Shai said that the authorities in China asked him to change the status of the Chinese deputy of the Institute's director. When he refused, they cut off the Institute's budget. After a year in which he refused to cede to their demand, the Chinese reversed themselves and even increased the budget. In another case, the event was not managed as well: a number of student supporters of Falun Gong[1] held an exhibition about the organization's activity in the main Tel Aviv University library. After a representative of the Chinese embassy demanded that the exhibition be removed, the Dean of Students ordered that it be removed – not in response to the Chinese demand, he said, but because it included offensive visual presentations that he did not approve. The court eventually ruled that the embassy had intervened and issued an order that the exhibition be restored.

Over the years, Shai has come a long way in his understanding of the Chinese superpower and in his attitude to it. As an enthusiastic socialist, his view of the Chinese system of government was positive, and he even believed that certain elements of it could be adopted in Israel. Various developments in China have diminished his enthusiasm and have shown him the other face of the Chinese entity. Today he is more critical and believes that a stand should be taken against some of China's initiatives that are incompatible with the principles of higher education and the state. He speaks proudly of the Dalai Lama's two unofficial visits to the Tel Aviv University campus, despite the objections communicated to him by the Chinese embassy. In his opinion, this fact, like many others, illustrates Tel Aviv University's responsible attitude and independence.

In order to act correctly with China, whether in business, higher education, or any other sphere, it is first necessary to understand China, its history, and the way that the Chinese people and leaders think. Shai believes that a good level of knowledge of the academic aspects has been achieved, although it is still not enough, and more time and resources are needed to attain the same extent and depth of knowledge that Israel possesses about Western countries and their culture. He notes approvingly that graduates of the East Asian Studies Department are now working in government ministries, embassies, higher education, and the private sector. Despite the knowledge accumulated and the presence of people with a good understanding of China in leading positions in the economy, however, there is still a gap in applying the safeguards mandated by the risks that China poses. For example, there is no comprehensive supervision of Chinese investments in Israel's private sector, which is liable to result in unwanted leaks of information to China. Similarly, there are joint studies with scholars from China in Israeli higher education, joint conferences, and other activities. Although this activity is welcome, its limitations must also be understood.

Prof. Shai believes that China will continue its efforts to penetrate Israel in a variety of areas – some innocuous, others not. Relocating the Chinese Embassy to its new compound in Ramat Hahayal in Tel Aviv will help make its actions more effective. On the Israeli side, Shai is concerned about the tendency of Israelis to become very friendly with the people with whom they interact – a characteristic that sometimes leads them to divulge too much professional information. Furthermore, Shai expects the Americans to become more active in the reduction of potential transfers of sensitive knowledge from Israel to China.

All in all, Prof. Shai cites favorably the revolution in Israel-China relations in the past 30 years. He adds, however, that these relations should be conducted judiciously and with awareness of Israel's historic and strategic relations with the United States.

__________________

[1] Falun Gong is a movement based on the Qigong exercise system. The movement's recruitment of many members in China is perceived as a threat by the Communist government, which has classified Falun Gong as an illegal political organization.

* This article is part of a series of articles marking 30 years of diplomatic relations between Israel and China.

** The authors thank Daniel Rakov and Tomer Barak for their helpful comments.