Publications

INSS Insight No. 836, July 21, 2016

On July 12, 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague issued its ruling on the case filed by the Philippines regarding its dispute with China in the South China Sea. The ruling, which clearly favored the Philippine position, stated that China’s claims to sovereignty in the “nine-dash line” area had no legal basis. According to the ruling, some of the territorial features in the area over which China demanded sovereignty are too small to confer territorial rights. Therefore, according to the ruling, China’s actions in Philippine waters violate international law.

In the months leading up the ruling, China stepped up its activity in the international theater, in view of the possibility that a political-military crisis was approaching. This article reviews the main points of the dispute and its implications.

Background to the PCA Ruling

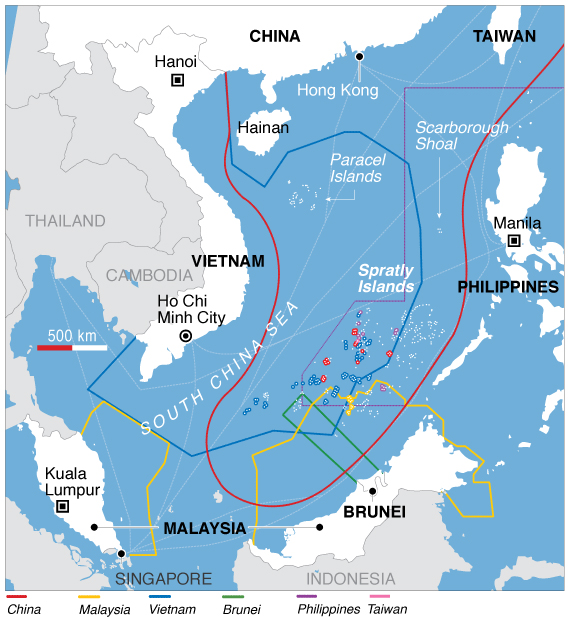

Given its strategic importance in international trade, fishing, and oil and gas potential, in recent years the South China Sea has become a much contested issue between six countries bordering it. In an effort to establish its sovereignty in the area and derive the most of the resources, in recent years China has constructed lighthouses and artificial islands housing military bases and civilian installations. Some of these areas, such as the Spratly Islands and the Paracel Islands, are claimed simultaneously by a number of countries.

In 2013, the Philippines, under then-President Benigno Aquino, filed for arbitration by the PCA in a case entitled “The Republic of the Philippines vs. the People’s Republic of China.” The arbitration was filed after China seized a shoal that both countries claimed was in their sovereign jurisdiction.

The Court’s ruling includes three main points:

a. The “nine-dash line” and historical rights demanded by China have no basis in international law.

b. None of the territorial features in the Spratly Islands meet the definition of an island under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

c. Restrictions on the movement and activity of Philippine ships by Chinese ships in the South China Sea are illegal. In addition, the construction of artificial islands, an intensive Chinese activity designed to bolster its territorial claims over the waters, was declared unequivocally illegal.

The precise legal definitions of the territorial features (e.g., islands, rocks, low-tide elevations) lie at the heart of the ruling, because each feature gives the country controlling it different rights in the area surrounding it. Islands entitle their sovereigns to 12 nautical miles of territorial waters and the right to declare an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around them to a range of 200 nautical miles. Rocks give their sovereigns rights only in 12-nautical mile territorial waters, while a low-tide elevation (LTE) gives its owner no rights whatsoever. The Court does not deal with the question of sovereignty over these territorial features, because this question is not within its jurisdiction. Without discussing China’s sovereignty over the marine land features in the “nine-dash line,” however, the Court substantially undermined the legitimacy of China’s claim to marine territorial and economic rights in the South China Sea.

China’s Attitude to Arbitration and its Interpretation of International Law

Beyond the context of the specific disputed points, the Court’s ruling has significance for international norms and law; the authority of international entities; China’s relations with neighbors beside the Philippines that also have disputes over rights in the South and East China Seas; and China’s relations with the United States. For its part, the United States has not taken sides in the dispute, but has consistently upheld a policy of protecting freedom of navigation and preservation of an international rule-based order, and has also increased its support for countries in the region concerned about Chinese policy.

Already in February 2013, China announced that it rejected the Court’s jurisdiction to hear the question because, China asserted, the main point in dispute was the question of sovereignty over the territorial features in the South China Sea, not the legal definition of those features, and the Court had no legal authority in the matter. China also claimed that the dispute should be solved through direct talks between the two parties.

China’s attitude toward the Court’s ruling has far-reaching consequences beyond the South China Sea. In public statements, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs emphasizes that China obeys international law and will continue to do so, arguing that in effect, the ruling itself constitutes a violation of international law, which China seeks to uphold. China has ratified UNCLOS (which the United States signed, but did not ratify), and its policy will therefore be an important precedent for obedience to international law and the behavioral norms of the major powers in general, especially toward small countries. If China ignores the ruling, this may weaken the authority of the international courts and their ability to exert actual influence. Researchers have also asked whether China aims to reshape the international system so that it serves its interests and culture better and reflects its current power in the global balance more effectively.

Mobilizing International Support

In advance of The Hague ruling, China took intensive action to build a broad coalition, asking many countries to declare that the dispute between China and the Philippines should be solved in direct bilateral talks without mediation. According to China, at least 66 countries support its views. The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) research institute has identified 65 countries that appear to be on this list. However, among them, only ten of the countries that China claims support its position (including Afghanistan, Gambia, and Kenya) have actually, as an official government position, declared their support for China. Four countries (Cambodia, Fiji Islands, Poland, and Slovenia) stated that China’s assertion of their support was incorrect. The remaining 51 countries (including Brunei, Belarus, and Ethiopia) did not officially declare their support for China, although they did not contradict the Chinese statement. China also declared that the Arab League supports it, and that this support was expressed at the seventh ministerial meeting of the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF), which took place in May 2016 in Qatar, but there is no public documentation of this. To date, Israel has refrained from taking a position on the question.

An examination of the countries supporting China, whether by declaring support or failing to deny it, shows a possible connection between China’s economic activity in those countries and their support for China’s position. On June 18, 2016 Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Serbia, where he signed 22 financial and infrastructure agreements, and said that China would support Serbia’s request to join the European Union (EU). On June 22, Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokeswoman Hua Chunying noted that Serbia was one of the countries supporting China’s position in the South China Sea. Serbia did not officially declare its support for China, but likewise did not deny it.

In an interview to the Chinese television station CCTV, Fatah Central Committee member Abbas Zaki expressed the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) unqualified support for China’s sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea on the one hand, and for solving the dispute through direct talks between the two parties on the other. This position is understandable, given China’s public and traditional support for the Palestinian positions in the conflict with Israel, but is particularly ironic, in view of the fact that the PA encourages international intervention in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and avoids direct bilateral negotiations with Israel.

Military Signals and Follow-Up Measures

Between July 5 (the day after US Independence Day) and July 11 (the day before the arbitration ruling), the Chinese navy conducted an exercise in the South China Sea in the area of the Paracel Islands controlled by China (over which both Vietnam and Taiwan claim sovereignty), declared a 1,300 sq km drill area, prohibited foreign ships from entering those waters, and fired missiles there. It is difficult to avoid interpreting this maneuver as a military signal of China’s political determination, despite its description in the Chinese media as “a routine and planned annual exercise.”

China’s future behavior depends on the actions of the other players, primarily the Philippines, other countries in the region, and the United States, but also on internal Chinese considerations. China has no interest in escalating the dynamic into military friction and conflict, but it is interested in deterring other countries from following the Philippines’ example, continuing to consolidate its status and claims, and maintaining the image among the Chinese public of the Chinese Communist Party leadership as determined to protect China’s national interest and pride. In a situation such as this, the parties are liable to be dragged into the use of military means, making control of escalation challenging. For example, reports recently circulated that China was considering declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the South China Sea in response to future pressure or provocations against it. Until now, China has exhibited determination in its statements, while maintaining maneuvering room and flexibility with respect to its actions.

Newly-elected Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte has declared his willingness to solve the problem through bilateral talks with China, especially if China aids his country in building infrastructure. This approach, which may reflect his realization that Manila has no effective means of enforcing the international ruling in its favor in the face of Chinese obduracy, increases the chances of a political-economic dialogue between the two countries. The PCA has no means of enforcing its ruling, and it is therefore likely that a solution to the dispute will be to send the two countries to the negotiating table.

Recommendations for Israel

Israel has refrained from joining UNCLOS, in part out of concern about being dragged unwillingly into international courts. This case is an example that shows that countries, even superpowers, have no control over a tribunal and its intervention. At the same time, had China taken an active part in the arbitration, it presumably could have influenced the ruling. This case therefore demonstrates the importance of taking an active part in the legal proceedings in international courts.

Where the South China Sea is concerned, Israel has no known public position on the matter in general, or on the issue of the current dispute in particular. On the one hand, Israel’s preference for direct negotiations with the Palestinians over international coercion is known, as is its interest in freedom of navigation and aviation. On the other hand, given the involvement of both the United States and China, it is recommended that Israel join the countries taking no declared official position in the dispute, and at most support its settlement through dialogue and peaceful means for the benefit of both sides.