Publications

Special Publication, July 8, 2024

This paper discusses the major trends in the portrayal of Jews and Israel in Muslim and Arab textbooks across the Middle East, North Africa, Azerbaijan, and Indonesia. The depiction of Jews ranges from vitriolic tropes typical of the traditions concerning the Prophet Muhammad’s seemingly tense relations with Arabian Jews to the influence of modern European antisemitism with a backlash against Zionist “settler-colonialism.” The textbooks also include positive references to the knowledge possessed by the “Israelites” and how they earned the respect of the prophet. Israel is mainly depicted negatively, portrayed as the bane of the Palestinians’ existence. With few exceptions, the textbooks ignore the Holocaust and the history of Jews native to the region. While curricula may be relatively free from anti-Jewish content but still contain anti-Israel material, the opposite case has not been observed. The more a country deviates from promoting a religiously moderate, inclusive vision that is sensitive to international norms of peace and tolerance, the greater the presence of the delegitimizing rhetoric against Jews and Israel in its textbooks. Consequently, countries that strive to elevate their curricula by adhering to higher standards of peace and tolerance often mitigate the radical discourse against Jews and Israel.

Major Trends in the Portrayal of Jews and Israel in Textbooks

The research assumption of scholars who study textbooks is that curricula reflect deeper currents within society, and they are usually more moderate and less volatile than other forms of public discourse.[1] Anecdotal evidence also indicates that school activities include radical elements that are not covered in the textbooks.[2] Focusing on official books, however, has a number of methodological advantages. Textbooks form a “sacred and living corpus” for the nation, consistently and systematically imparting society’s vision for the future.[3] Textbooks are the filter through which the younger generation receives its religious, civil, national, and social lessons. We must, therefore, observe the treatment of “others” outside the national group from the perspective of the overall national vision presented in textbooks, and whether those “others” help to fulfill it or threaten it.[4] In the present case, the perceived “others” that we examine are the Jews and Israel, including Judaism and Zionism. This short paper aims to analyze the main trends in the portrayal of Jews and Israel in textbooks of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, Azerbaijan, and Indonesia. The way they are depicted across different curricula varies greatly in style, length, extent to which specific aspects are accepted or denounced, and so forth. However, for the sake of this discussion, we have identified two main types of curricula: one is followed by countries promoting a religiously moderate, inclusive vision sensitive to international norms of peace and tolerance, such as the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Morocco, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Indonesia. The other is followed by countries espousing Islamic fundamentalism and socially regressive ideas, for whom the existence of Palestine relies on totally delegitimizing Israel and, to some extent, Jews, and include Iran, Syria, Iraq, and the Yemeni Houthis. In addition, there is a sub-category of countries—namely Qatar, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority (PA)—that espouse some of the worst views against Jews and Israel in their textbooks, despite having long-standing engagements with them.

The textbooks in question portray Jews and Israel in a diverse manner, but there are some similarities in the presentation of these themes over the years. Most involve negative (and rarely positive) references to the Jews in the Qur’an, Hadith, and early Islamic history, and to Israel in the context of the Zionist movement, the “Palestinian cause,” and the wars and peace agreements with Arab nations. Another aspect is the influence of modern Western antisemitism, which was first adopted by radical Islamists and later by radical nationalists, largely through interactions with German and Soviet propagandists during the 20th century.[5] By portraying Israel as a colonialist country, it is labeled as a pariah state and further fuels those who seek to harm its legitimacy.

Regional Factors to Consider

Several factors influence attitudes toward Israel and the Jews in the MENA curricula. The first factor is the nuances of outlooks positioned between the opposing ends of the main Middle Eastern religiopolitical spectrum—the rejectionist-Khomeinist block largely affiliated with Iran and its Shiite proxies and the Palestinians, and the moderate-inclusive block largely associated with the Sunni countries that are closer to Israel. Turkey, Qatar, and Jordan are each special cases that harbor an overarching attitude of ambivalence toward Jews and Israel. However, the positioning of curricula along this spectrum can be swayed by the identity of the educators who develop the curricula and the authors. In what may be regarded as educational and intellectual negligence, in quite a few cases, the authoring process of textbooks is outsourced to authors and publishing houses whose staff spread hate and intolerance toward others, especially Jews and Israel.[6]

A second factor is the tension between national and supranational ideologies, the latter being, for example, denominational-Islamic (Sunni or Shiite), pan-Arabism, pan-Turkism, neo-Ottomanism, pan-Iranianism or pan-Kurdism. Minority groups across the region could stand in conflict with the national vision and/or the supranational ideology.[7] Other elements of national identities in the region are that claims to descending from pre-Islamic ethnic groups to bolster their legitimacy, indigenousness, and purity of race (Pharaonic Egyptian, Moabite Jordanian, Canaanite Palestinian, Babylonian Iraqi, Aryan Iranian, Semitic Arab and so forth). These elements of race, language, ethnicity, and roots can play out for or against improving relations with Israel, just as conflicting interpretations of Islam can perform opposing roles. Hence, in today’s Middle East, Israel’s independence is incompatible not only with Palestinian nationalism, but also with most of the supranational identities espoused by the rejectionist-Khomeinist vision that revolves around the centrality of military jihad and incessant expansionism. The moderate-inclusive vision, however, aims for a loosely interconnected and collaborative regional structure that keeps nation-states separate and independent. Naturally, this vision can tolerate and even welcome the Israeli presence. Nevertheless, the unyielding Arab-Islamic support for the Palestinian cause serves as a unifying vision in itself.

A third factor is the processes of identity consolidation undertaken by the countries in the region, which manifest the underlying tensions that persistently shape the periodization of history into three main layers—pre-Islam (pre-monotheistic), Islamic, and post-Islamic.[8] The Jews and Israel, anachronistically, are likewise focal points of tensions that cut across each layer. The Jews or “Israelites” are among those pre-Islamic and even pre-Monotheistic tribes that were rejected by Islam and are perpetually regarded as “others.” Paradoxically, although the Israelites are acknowledged as being the source of monotheism, Judaism, as a religion indigenous to the region and one that still thrives, is not recognized. In the Islamic layer, the existence of Jews is contextualized as either deserving or undeserving of respect; that is, should they and their Judaism be accepted per se, should they be seen as part of the Islamic civilization, or should they be rejected altogether. Consequently, Jews and Judaism are constantly weighed against Arab and Islamic elements. In the post-Islamic layer, the revitalization of Hebrew, the Jewish language, and the Jews’ pursuit of political independence through Zionism are closely associated with Western colonialism and hegemony, viewing Israel as a bridgehead created by “Western” colonizers. Therefore, Israel and Jews in the post-Islamic layer are recognized as elements that may have adverse, neutral, or conducive effects on society.

Reflecting the vision of the Islamic Republic, Iranian textbooks indicate that Israel’s existence thwarts the possibility of unifying the region into a single Iranian-led revolutionary Islamic state, which would control the sea lanes and natural resources.[9] Israel’s existence certainly does not allow the establishment of a Palestinian state in “historical Palestine,” and therefore the “Israeli other” should somehow vanish. In contrast, the Pharaonic Egyptian national vision is almost unaffected by Israel’s existence.[10] Egypt thus can pursue its vision and attain collective “ontological security,”[11] with or without Israel.

Elements of Content

There are typically three main sources of hatred toward Jews—the Palestine issue / Arab–Israeli conflict, theological issues stemming from tensions between Jews and Muslims in the 7th and 8th centuries, and Western-inspired antisemitism. References to Jews in textbooks largely depend on the subject matter and the extent of the country’s conflict with Israel and the West. Islamic Education textbooks across all state curricula contain varying degrees of anti-Jewish content, primarily focusing on the conflicts between the Prophet Muhammad and the Jews of Medina. Consequently, the Jews may be described as treacherous, conspiring against the Muslims, with references to their significant influence on early Islamic commerce and finance.

Identifying the trends of how Jews and Israel are depicted in the region’s textbooks is not a straightforward task. Methodologically, we need to distinguish between the depictions of Jews in the inclusive/exclusive Islamic or European narratives, as opposed to the modern portrayals of Israel and Zionism which are often tinged with Western antisemitism or Islamic anti-Judaism. These portrayals are often intertwined. Furthermore, it is important to study how these depictions change over time. Textbook editions typically undergo changes either by completely overhauling previous material and introducing new content, or by removing, altering, or adding content. When problematic content is eliminated, it helps mitigate the overall impact of the textbook as a whole, presenting a less biased or more accurate narrative. However, in a few cases, despite the changes to the content, the textbooks still contribute to bigotry, hate speech, incitement, or historical inaccuracy. Those who are committed to military struggle, violent unification of the region, and “resistance” often continue to teach Western antisemitism alongside conspiracy theories and elements from popular war and anti-colonialist discourses, in which Israel plays the role of the settler-colonialist.

As we will see, a more positive portrayal of Jews can be found in countries that have been moving away from direct or indirect conflicts with Israel and have been seeking a closeness with the West, namely the UAE, Turkey, Morocco, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Indonesia. Although all the countries in this study express their commitment to the Palestinian cause, and are generally critical of Israel, the aforementioned countries differ in the extent of the antisemitic/anti-Jewish rhetoric combined with the portrayal of Israel as well as the degree to which they recognize Israel’s right to exist. Hence, the moderate-inclusive countries still criticize Israel but are gradually disentangling portrayals of Israel from the depictions of Jews and are willing to acknowledge Israel’s right to exist. It can be generalized that the countries in this category (referred to as promoting a religiously moderate, inclusive vision that is sensitive to international standards of peace and tolerance, or in short “moderate-inclusive”) are mostly Sunni Muslim countries that have signed peace treaties with Israel or have embraced the Abraham Accords.

Conversely, the harshest anti-Jewish and anti-Israel rhetoric is promoted by countries that combine the worst aspects of both (referred to as “fundamentalist” and “regressive”). Specifically, these countries mainly adhere to the vision of ending the state of Israel promoted by Iran, the PA, and Hamas. Jordan is an exception to this, as it has a peace treaty and strategic cooperation projects with Israel, but its curriculum is extremely problematic and is quite similar to the PA curriculum in its portrayal of Israel and Jews. This is largely due to the significant influence of the Palestinian population in Jordan. Another exception is Qatar, which has removed some antisemitic content but left other elements intact. The following section will expand on these two types of curricula.

Moderate-Inclusive Curricula

In many moderate-inclusive curricula, Jews and Judaism are portrayed positively, based on occasional Qur’anic praise of the Jews’ knowledge of scripture, the Torah as an authoritative text, or their inclusion in the category of protected groups known as the ahl al-kitāb or “People of the Book.” For example, a 9th grade Islamic Education textbook in the UAE encourages tolerance toward non-Muslims, specifically the People of the Book, by “strengthening connections with them” through constructive dialogue and coexistence.[12]

Thus, countries like the UAE, Turkey, Morocco, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt that aim to present their curricula as more responsible, moderate-inclusive and in line with international standards of peace and tolerance, have gradually highlighted these positive aspects and moderated or removed some of the existing problematic contents.[13] For instance, the identification of Jews with “unbelievers” (kuffār) has gradually been effaced from some curricula, as is the anachronistic contextualization of Arab–Israeli conflicts in the Islamic discourse of Jews rejecting Islam, Muhammad and the Qur’an. Saudi Arabia, for example, has removed most cases of Islamic anti-Jewish tropes from its curriculum, including a Social and National Studies lesson that portrayed the Jews of ancient Medina as trying to fight Muhammad and Islam, describing them as having a “treacherous and perfidious nature.”[14] Instead, new content has been added to the Saudi curriculum about Muhammad’s treaties with various peoples, including the Jews, and the constitution of Medina, which protected all inhabitants of Medina, regardless of religion, and allowed them to freely practice their religion. This new content aims to show the tolerant nature of Islam and pave the way for further agreements with Jews.[15]

An extremely positive change in recent years is the gradual disappearance of the Western-inspired antisemitism from school textbooks in countries that share the vision of thriving through regional, peaceful cooperation. A prime example is again that of Saudi Arabia, which removed a statement from a 2017 textbook on Islam that affirmed the existence of “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” As the textbook stated:

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: They are secret decisions that seek the control of the Jews over the world. They were likely [originated] in the Basel Conference [the First Zionist Congress]. They were exposed in the nineteenth century. The Jews tried to deny them, but there is abounding evidence that they were genuine and published by the elders of Zion.[16]

Countries with a rich history or a significant presence of local Jewish culture also include references to Judaism in the Arabic Language and Social Studies textbooks. Morocco is perhaps the only country that has highlighted the contribution of Jews of Morocco to its society and culture. This can be seen from several examples, such as lessons in the Arabic Language textbooks referring to Jewish celebrations on the Sabbath (such as cooking the skhina, a traditional Moroccan Jewish dish for Sabbath), where they “congratulate each other during religious holidays, whether Islamic or Jewish.”[17] In addition, Indonesia has noted the importance of Jews and the Hebrew language in the golden age of Islam.[18]

The history of the Jewish Holocaust is generally not taught as part of the curricula, with the exception of Turkey, Azerbaijan (whose textbooks also show respect for Judaism),[19] and the specific curriculum geared toward the small Christian minority in Indonesia. In early 2023, the UAE announced that the Holocaust would be taught in history classes, but to the best of our knowledge, this has not yet happened.[20]

Turkey’s reference to the Holocaust is evident in a 12th grade history textbook in a section noting the repercussions of World War II and the Nazi regime. As shown in Figure 1, the text also briefly covers Kristallnacht (Night of the Broken Glass), in addition to Auschwitz, and the “5.1 million victims,” including Jews and others such as Roma and Soviet POWs who were killed by the Nazis.[21] The Holocaust is mentioned but its presentation as primarily a Jewish event is somewhat downplayed. For example, the textbook states that “With the start of World War II, Jews, Roma and the people in the [German] occupied regions were subjected to genocide (Holocaust) in gas chambers and ovens in concentration camps.”[22] While the textbooks do not discuss the persecution of Jews in Turkey during this period, the recognition, albeit limited, of the most significant trauma affecting Jews in modern times is noteworthy.

Figure 1. A photograph of a synagogue that was set on fire during Kristallnacht, which appears in a Turkish history textbook

It should be noted that some countries may have multiple curriculum systems, and while one may be moderate-inclusive, another may be fundamentalist. In Egypt, for instance, there are both the general public curriculum and that of the al-Azhar religious school system, and these two curricula differ in their treatment of Jews.[23] The public curriculum textbooks have been entirely rewritten as part of an educational reform in 2018, and they have made significant strides in differentiating between criticism of Israel (which has been reduced to some extent) and criticism of the Jews, which often invokes antisemitic tropes. For example, a lesson in a 5th grade Islamic Studies textbook (2021‒2022), which has since been removed, drew parallels between the Egyptian army’s victory over the Israeli forces in the Yom Kippur/October War of 1973 and the Prophet Muhammad’s victory over the Jewish Banu al-Nadir tribe in the 7th century. This example was particularly inflammatory because it attempted to link the “holy war” against the Jews with contemporary events in the history of relations between Israel and Egypt. For example:

Then the father pointed to the other side, saying: And these are the fortifications of the Bar Lev Line. Allah helped us against the Jews just like when He helped the Messenger against them in Medina, destroying their fortifications with them inside.[24]

Israel is not mentioned by name in this lesson; instead, it is referred to as the “enemies” or “usurping Jews.” The lesson emphasizes the stereotype of Jews as betraying others, stating that “they are always like this.”

Unlike the public system, which has eliminated many harmful expressions about Jews and Israel, the Al-Azhar textbooks still contain inciting examples, making them regressive and extreme. For instance, according to a Principles of Religion textbook for the 8th grade, the Jews of Medina violated their agreement with the Muslims, due to their unavoidable treacherous nature.[25] In contrast, religious textbooks for Egypt’s Coptic minority acknowledge the Jewish roots in the Land of Israel, with one of the textbooks referring to Judea as bilād al-yahūdiyya (literally “Land of Jewry” or “The Jewish Land”).[26]

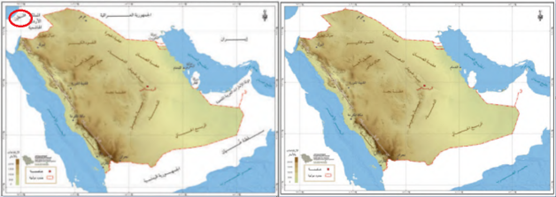

The issue of recognizing Israel is also illustrated through maps. The name “Israel” rarely appears, with the exception of some UAE textbook editions, and instead, the region is referred to as “Palestine” or “Occupied Palestine.” Some moderate-inclusive curricula have increasingly adopted a methodology of leaving the geographical area unnamed. In the Saudi curriculum, for instance, the maps either give the name of the area as “Palestine,” leave it unnamed, or even acknowledge the existence of the “Green Line” (the 1949 Armistice demarcation).[27] In some cases, the names of other countries have also been omitted in the Saudi curriculum, as seen in Figure 2. This approach provides an elegant solution for remaining neutral on the Israel/Palestine border issue and can be easily justified to critics. Although it is a slight improvement over naming the entire area “Palestine,” the non-recognition of Israel is still problematic, as it fails to acknowledge reality.

Figure 2. Left: In the Saudi high school Geography textbook, 2021, “Palestine” appears on the top left corner. Right: In the high school Geography textbook, 2022, only Saudi Arabia appears, with no other countries mentioned, including Palestine

It can be argued that the moderate-inclusive countries, to varying degrees, have acknowledged that Jews and Israel are “here to stay”—an understanding which has led to two main visions embraced by these countries. The first vision promotes significant measures to eradicate any incitement against Jews or Israel and not yielding completely to opposition pressure, as is the case chiefly with Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Egypt.[28] The second one reluctantly accepts Israel’s existence but due to the susceptibility to pressure from opposition voices, these countries focus on mitigating antisemitic/anti-Jewish content, separating it from their critical and often inflammatory views on Israeli policies, such as in the case of Bahrain.[29]

Fundamentalist and Regressive Curricula

Fundamentalist and regressive curricula seem to be motivated primarily by two sentiments: securing Palestinian justice over Israel’s ruins and promoting a vision where Jews are portrayed as second-rate subjects at best. These sentiments can be observed in the curricula of the Palestinian Authority, Hamas, Jordan, Syria, Yemeni Houthis, Iraq, and Iran.[30] Hence, countries and entities engaged in direct or indirect conflict with Israel rarely attempt to moderate the antisemitic portrayal of Jews. Instead, the political hostilities appear to further fuel anti-Jewish hatred. As such, Jews are continuously maligned as the enemies of Islam in the various textbooks. The Palestinian curriculum, for instance, implies that Jews are the “enemies of Islam in all times and places.”[31] The Syrian textbooks teach a pan-Arab revolutionary worldview that suggests its universalism is incompatible with the “prejudiced” exclusionist nature of Judaism.[32] Furthermore, antisemitic motifs such as stereotypical references to the character of Shylock from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice are found.[33]

In the curricula of the Yemeni Houthis, Iraq, and Iran, the portrayal of Jews is often tinged with Shiite sentiments. The interests of the Jews are seen as aligned with those of the Sunnis, with the curricula emphasizing that Judaism is like that of Sunni Islam, perceived by Shiite Muslims as “others.” For example, the Houthi material depicts Jews as universally evil, being “the most hostile people to the believers” and “cursed by God”—revilements that extremist Shiites also apply to the Sunna.[34] In the Iranian curriculum, even Kaʿb al-Aḥbār, a prominent Jewish convert to Islam, is blamed for falsifying Hadith religious traditions in support of the anti-Shiite Umayyad dynasty.[35] In parallel, these study materials preach in different ways pan-Islamic solidarity against Israel and the West.

Mentions of Israel are generally negative, with very few exceptions. Lessons about Israel, Zionism, and modern Judaism are mostly found in Social Studies, History, or Geography textbooks, although there are also references in Islam or Arabic Language textbooks. For example, an 8th grade Arabic Language textbook used by the Palestinian Authority teaches reading comprehension through a violent story that promotes suicide bombings and exalts Palestinian militants in the Battle of Karameh, as shown in Figure 3. The story describes the militants as they “cut the necks of enemy soldiers” and “wore explosive belts, thus turning their bodies into fire burning the Zionist tank.” Israeli forces are described as “leaving behind some of the bodies and body parts, to become food for wild animals on land and birds of prey in the sky.” An accompanying illustration at the beginning of the story depicts Israeli soldiers in a tank, shot dead by a Palestinian gunman.[36]

Figure 3. The story of the Battle of Karameh

As per the regressive curricula’s unwavering support of the Palestinian cause, Israel’s right to exist is completely rejected, often harnessing Islamic discourse to demonstrate the jihadi duty to free Palestine. In the Syrian curriculum, all means of fighting against Israel—“the racist Zionist Entity”[37]—are deemed legitimate.[38] In the Iranian textbooks, for example, animosity toward Israel is exemplified not only by highlighting its threat to Iran, but also to other Muslim nations, primarily the Palestinians. For instance, the 8th grade Social Studies textbook emphasizes that the Palestinian question and the fight against Zionism are relevant to all Muslims and specifically related to the future and development of Iran.[39] An Iranian 12th grade Sociology textbook encourages Muslims to “apply the jurisprudential situation of the world of Islam, to properly address and resolve the Palestinian issue,” teaching that Islamic jurisprudence behooves Muslims to “resist attacks on the borders of the Muslim world,” thus also implying the involvement of Western powers wherever Muslims reside.[40] In the PA curriculum, a 10th grade Islamic Education textbook teaches that jihad is “for the liberation of Palestine” and is presented as a “personal obligation incumbent upon every Muslim.”[41]

The Jordanian curricula is also profoundly anti-Israeli, arguably influenced by the significant percentage of the Palestinian population in the country. This is evident to the extent that following the October 7 massacres, it was reported that a 10th grade Civics textbook introduced a section about the events, justifying the Hamas attacks against “the Israeli enemy,” describing Israeli civilian hostages as “settlers,” blaming Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians for provoking the attacks, and accusing them of committing an “attack of mass destruction” against the Palestinians.[42] However, while reports from February stated that the new passage was removed from the textbooks, as of June 17 it is still featured in the edition available online at the National Center for Curriculum Development website.[43] This indicates that proper criticism of incitement and violence in textbooks may lead to swift changes, provided that relevant authorities and decision-makers are willing.

Qatar is a good example of a country that has an ambivalent position toward the portrayal of Jews and Israel.[44]Although Qatar aims to meet international norms of peace and tolerance, at the same time, it has accommodated Hamas’s views and harbors its key figures. Thus, Qatar removed much of the explicit antisemitic and anti-Jewish content from its textbooks in 2021, but it still continues to legitimize and glorify violence against Israel in both historical and contemporary contexts. For example, a Qatari textbook from 2017 contained apologetic messages explaining Nazi hatred toward Jews, such as Nazi Germany’s “canceling the rights of the Jews because they had a great impact on the defeat of Germany in the First World War.”[45] This content has been removed, and the Holocaust is no longer mentioned at all.

Nonetheless, Qatari textbooks still share other hateful content, particularly as it relates to Israel. For instance, the internationally recognized territory of Israel in its pre-1967 borders is labeled as “Occupied Palestine.” Muslim obligations toward Palestine include to “exert any effort” to liberate Palestine from “the Occupation,” while “not conceding on any part of Palestine, for it is an Arab, Islamic land.” Furthermore, the textbooks share religiously motivated polemic that teaches that Jews are materialistic and arrogant in their beliefs, disobedient to Allah, and inherently hostile to Islam and Muslims.

Qatari textbooks promote a narrative that denies Jewish historic ties to the region of Israel/Palestine and portray Jewish self-determination as unjustifiable, racist, and cynical. The textbooks also lack information that could foster empathy or understanding of the Jewish experience, such as the history of Jews in the Arab and Islamic world or the Holocaust.[46] Moreover, violent jihad and glorification of martyrdom remain part of the Qatari curriculum. The curriculum consistently employs a pro-Arab, anti-Israel nationalist narrative, portraying Israel and Israelis as a malevolent force devoid of human motivations and undeserving of empathy. This narrative is contrasted with the unquestionably just Palestinian Arab cause. In serving this narrative, Qatari students are taught historically dubious or unfounded ideas, such as the myth that the ancient Canaanite people, who inhabited present-day Israel/Palestine, were Arabs.[47]

Despite the unyielding approach of the fundamentalist and regressive curricula, there are rare cases where the existence of Jews and Israel is accepted as fact without challenge. For example, a Syrian textbook acknowledges the Agreement on Disengagement (1974) between Israel and Syria as valid to this day.[48] The Iranian curriculum presents Iran as a country tolerant toward its ethnic minorities, including Jews.[49] Clearly, there is a distinction between the Jews of Iran, who have proven loyalty to the Islamic Republic, and foreign Jews. Although the peace agreement between Jordan and Israel is largely ignored, the Jordanian textbooks do show some pragmatism toward Israel, by presenting Jordan as accepting some responsibility for the Arab rejection of the 1947 partition plan and the subsequent 1948 Arab invasion.[50] Even Qatar has removed some problematic examples about Jews and Israel, such as accusing the Jews of manipulating the economy that gave rise to the Nazi Party,[51] as well as describing Hamas as “brave” and “remarkable” for firing thousands of rockets at Israel.[52]

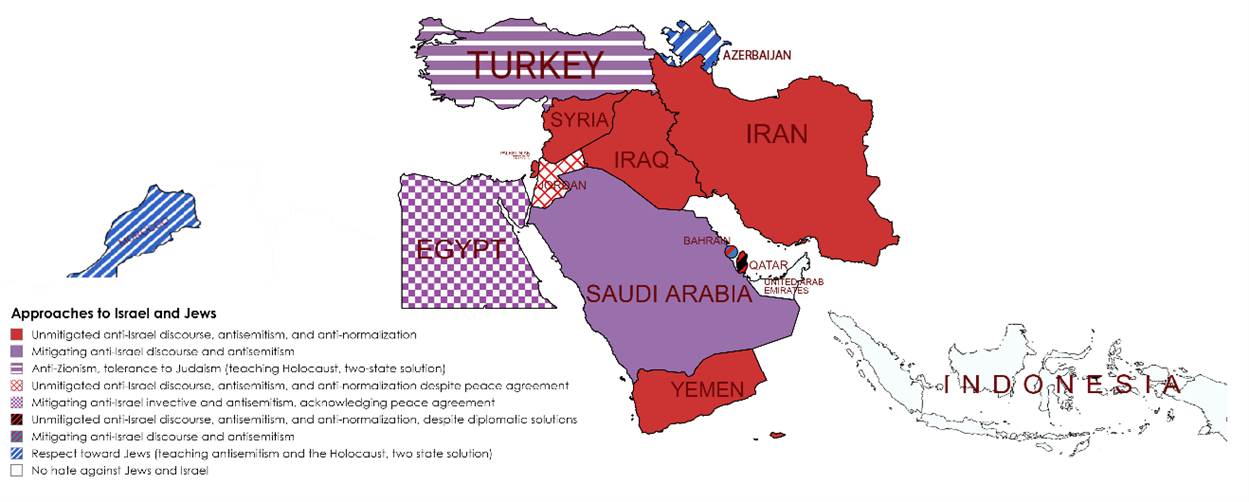

Figure 4 demonstrates the major trend lines in the region vis-à-vis Israel and Jews. Whereas red signifies countries with the harshest, most intolerant approach, blue represents countries that have the most tolerant curricula, and purple is for those countries that have a middle way approach. White represents those countries whose curricula have little reference and interest in Jews and Israel, and without noticeable hatred toward them.

Figure 4. Approaches to Israel and the Jews

Conclusion

In examining how Jews and Israel are portrayed in the curricula of the MENA countries, Azerbaijan, and Indonesia, we proposed a clear distinction between countries that promote a religiously moderate, inclusive vision that is sensitive to international standards of peace and tolerance (UAE, Turkey, Morocco, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Azerbaijan, Indonesia), and countries that espouse religious fundamentalism and socially regressive ideas and dehumanize Israel and Jews (Iran, Syria, Iraq, the Yemeni Houthis, Qatar, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority).

The overarching similarities notwithstanding, the differences in curricula within each category are quite nuanced. These nuances usually result from different policies a country has toward Israel as well as their distinct social-cultural aspects. For example, while Jordan has a peace agreement with Israel and, unlike the PA or Iran, is not involved in direct or indirect warfare with it, it is nonetheless extremely influenced by the large presence of Palestinians in Jordanian society. Even though it teaches about the Holocaust and a two-state solution, Turkey is highly critical of Israel, perhaps reflecting the deteriorating relations with Israel over the recent decade; however, its textbooks generally respect Jews.

In contrast, Egypt seems committed to curriculum reforms aimed at mitigating anti-Jewish, antisemitic, and anti-Israel material, but the educational corollaries of the October 7 war should be examined. Although the UAE and Morocco are categorized alongside Egypt and Saudi Arabia, their attitudes toward Israel and Jews are far more positive and inclusive than those of Egypt and Saudi Arabia, likely due to their commitment to the Abraham Accords and moderation. In Morocco’s case, one must consider their embrace of cultural inclusivism and pluralism, particularly regarding the contributions of Morocco’s Jewish population to its society. Indonesia takes a rigid “anti-colonialist” approach of delegitimizing Israel and does not teach about Judaism, while Azerbaijan teaches about Judaism, antisemitism, and the Holocaust and recognizes Israel. Distance from Israel may also influence the degree to which the curriculum reflects policy, as in the cases of Tunisia and Qatar, whose curricula reflect a seemingly conscious attempt on behalf of their governments to highlight Israel’s impingement on the Palestinian cause.

As the reports of IMPACT-se have shown on multiple occasions, improvements in the portrayal of Jews and Israel in textbooks are possible. When there is a will, decision-makers and relevant ministries can and do introduce swift changes. International pressure is useful to a limited extent when dealing with entities blatantly hostile to Israel that depend on foreign Western funding, such as UNRWA or the PA. In the long run, changes may also trickle down to parts of the radical block (think Iraq). However, a persistent educational effort via media outlets and social networks will be needed to prepare the ground for justifying the removal of harmful contents to a public indoctrinated to hate Israel and Jews. As mentioned, more promising is the situation with countries appreciating moderation, modernity, and sophistication. For them, the path of diplomacy—opening a direct channel to education officials—is most often the preferable option. Exposing information that demonstrates potential anti-Israeli bias may also contribute to overall educational policies, for example by encouraging the relevant ministries to better scrutinize the origins of their curricular development.

In light of the historical periodization of history into three layers mentioned above, a fourth layer is emerging—the “pan-Abrahamic era” that is based on the Abrahamic discourse and other outlooks envisioning a peaceful, moderate, and inclusive Middle East for all its inhabitants, including Israel and Jews. For a regional initiative and vision in the spirit of the Abraham Accords, a larger joint “pan-Abrahamic” effort of educational teams representing countries and minorities will be needed. The various platforms established thanks to the Abraham Accords and other regional dialogues should be used to promote curricular reforms, to include more values of peace, tolerance, and coexistence and to remove harmful content.

Removing the harmful material described in this review is only part of what is needed. A lot is missing, from empathetic information on Jews and Israelis, their unique history and indigenousness, to recognition of the State of Israel in text and on educational maps. For the countries committed to this vision, the pan-Abrahamic initiative would be a gateway for benefits, where access to shared experiences and best practices for curricular reform are just the tip of the iceberg. That said, curricular reform must be achieved from within the country according to its cultural sensibilities and sensitivities. Thus, countries committed to this pan-Abrahamic vision must show forbearance and not be swayed by anti-normalization voices that are often vocalized from the opposition benches.[53] There is much learning to do through a dialogical process among those who design the MENA curricula and beyond. If elites across this region are determined to lead it to an age of efflorescence, they must educate the young generation in the spirit of Abraham, Sarah, and Hagar. In other words, they should embrace Israel and the Jewish people—among other ancient minorities—as an inseparable and critical piece of the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean mosaic.

_____________________

* This article is published as part of a joint research project of INSS and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which deals with the perceptions of Jews and Israel in the Arab-Muslim sphere and their effects on the West. For more publications, please see the project page on the INSS website.

[1] See, for instance, Michael Young, “The Curriculum as Socially Organised Knowledge,” in Robert McCormick and Carrie Paechter (eds.), Learning & Knowledge (London: Paul Chapman and The Open University, 1999), 56–70.

[2] According to anecdotal evidence, this is particularly true for semi-independent subgroups within nations, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Palestinian Authority, the Houthis in Yemen, Hamas, and the Israeli National-Religious curricula. On education in the PA, see IMPACT-se, “UNRWA’s Education: Textbooks and Terror,” (November 2023); UN Watch and Impact-se, “UNRWA Education: Reform or Regression: A Review of UNRWA Teachers and Schools Concerning Incitement to Hate and Violence,” (March 2023). About Hamas’s curriculum, see IMPACT-se Staff, “Al-Fateh – The Hamas Web Magazine for Children: Indoctrination to Jihad, Annihilation and Self-Destruction,” (2009). About the curriculum in Yemen, see Itam Shalev, “Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen 2015–19,” (IMPACT-se, 2021). On Hezbollah’s education, see “Hezbollah’s ‘Education Mobilization,’” The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center, July 27, 2019; “Youth Movement Affiliated with Hezbollah Spreads Messages of Violence, ” IDF, November 20, 2014. Catherine Le Thomas, Socialization Agencies and Party Dynamics: Functions and Uses of Hizballah Schools in Lebanon, edited by Myriam Catusse and Karam Karam (Beirut: Presses de l’Ifpo, 2010), 217‒249.

[3] For a discussion on curricula as a scripture-like genre and on the methodology of Curriculum-Informed Strategic Assessment (CISA), see Eldad J. Pardo and Ofir Winter, “Israel and Jews in Egyptian Textbooks: A Forward-Looking Perspective,” INSS (February 4, 2024), 3‒7. See also Elie Podeh and Samira Alayan, eds., Multiple Alterities: Views of Others in Textbooks of the Middle East (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 1‒4; Ben Williamson, The Future of the Curriculum: School Knowledge in the Digital Age (Cambridge, MA and London: The MIT Press, 2013), 115.

[4] An intriguing example of the use of “othering” to elucidate social boundaries and solidify identity is the development of Shiite Islam. Modern Shiite methods of “othering,” such as cursing and vilifying, have substituted their classical Sunni others (primarily the enemies of ‘Ali and ahl al-bayt) with their modern “others,” such as the West, Israel, Salafists, Bahais, and more. See Meir Litvak, Know Thy Enemy: Evolving Attitudes Towards “Others” in Modern Shi’i Thought and Practice (Leiden: Brill, 2021). On medieval Twelver Shiite views on delegitimizing the Companions of the Prophet Muhammad, see Yonatan Negev, “Cursing the Companions of the Prophet Muḥammad (la’n al-ṣaḥāba) in Pre-Modern Twelver Shi’i Religious Thought” (PhD Dissertation, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2023).

[5] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Hajj Amin Al-Husayni: Wartime Propagandist,” Holocaust Encyclopedia; Joel S. Fishman, “The PLO’s People’s War,” Nativ: A Journal of Politics and the Arts, Ariel Center for Policy Research 16, no. 6(95) (November 2003); Matthias Küntzel, “Islamischer Antisemitismus,” CARS Working Papers, No. 4, Center for Antisemitism and Racism Studies (2022). See also the diverse statements that make up the IHRA’s non-legally binding working definition of antisemitism.

[6] Elements of the curricula regarding Palestinian issues often bear surprising similarities to the Palestinian “party line.” Islamic textbooks in Qatar were found to be authored by Muslim Brotherhood activists. See MEMRI, “Review Of Qatari Islamic Education School Textbooks for the First Half of the 2018‒2019 School Year” (Washington, DC: MEMRI, 2019), 7. Since 1991, some of the Bahraini curriculum (social studies, history, and Arabic language textbooks) has been authored and developed, among others, by experts from GEOprojects, a large educational publishing company headquartered in Beirut. Textbooks that it published for the Bahraini curriculum include Modern and Contemporary Arab History (Society 213), 2021, for high school grades; Arabic Language: Ancient Arab Poetry (Arabic 213), 2009–2010, also for high school grades. GEOprojects also has branches in the UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, Iraq, and Kurdistan, as well as agents and representatives in Egypt, Jordan, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Libya, Algeria, and Sudan. The company is closely associated with several leading educational publishers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, notably Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, which has granted GEOprojects the exclusive rights to translate and adapt its Math and Science Series for Arab learners. About GEOprojects, see http://www.geo-publishers.com/Home/About; and about “The Social Studies Series,” see http://www.geo-publishers.com/Home/Eprograms.

[7] Greek and Armenian nationalism in Anatolia, for example, was in conflict with not only Turkish nationalism but also pan-Turkish and pan-Islamic perceptions, both of which are integral to modern Turkish nationalism.

[8] According to P. R. Kumaraswamy, most countries in the Middle East suffer from an identity crisis due to their inability to foster an inclusive and representative national identity. See P. R. Kumaraswamy, “Who Am I? The Identity Crisis in the Middle East,” Middle East Review of International Affairs (MERIA), 10, no. 1 (March 2006), 63. That inability, we believe, is partly due to the difficulty of reconciling the tensions that pervade a state’s myriad of identities and narratives, most of which can be stratified along the three main periods. Thus, as a reflection of national identity, the success of a state’s curriculum depends on its ability to be inclusive and representative of the various identities that exist within that state.

[9] Eldad J. Pardo, “Iran’s Radical Education: An Interim Update Report, 2021–22,” (IMPACT-se, 2022).

[10] Ofir Winter, “Generational Change: Egypt’s Quest to Reform its School Curriculum,” (IMPACT-se, 2023).

[11] Jennifer Mitzen, “Ontological Security in World Politics: State Identity and the Security Dilemma,” European Journal of International Relations 12, no. 3 (2006): 341‒370.

[12] For full analysis of the example see IMPACT-se, The Emirati Curriculum 2016–21 Grades 1–12 (2022), 33.

[13] Eldad J. Pardo, “When Peace Goes to School: The Emirati Curriculum 2016–21,” (IMPACT-se, 2022); Hay Eytan Cohen Yanarocak, “The Erdoğan Revolution in the Turkish Curriculum Textbooks,” (IMPACT-se, 2021); Itam Shalev, “The Moroccan Curriculum: Education in the Service of Tolerance,” (IMPACT-se, 2023); IMPACT-se, “Bahrain Report,” forthcoming; IMPACT-se, “Updated Review: Saudi Textbooks 2022–23,” (IMPACT-se, 2023); Winter, “Generational Change.”

[14] Social and National Studies, 7th grade, Vol. 2 (2017), 86. See IMPACT-se, “Updated Review: Saudi Textbooks,” 162.

[15] Saudi Arabia, Islamic Studies – Hadith (2), 10th–12th grades, Pathways System (2022), 84; Saudi Arabia, History, 10th–12th grades, Courses System (2022), 76.

[16] Saudi Arabia, Hadith and Islamic Culture 1, 10th–12th grades, Level 2 (2017), 204. See Eldad J. Pardo and Uzi Rabi, “The Winding Road to a New Identity: Saudi Arabian Curriculum 2016–19,” (IMPACT-se, 2020), 103.

[17] Morocco, Arabic Language (Moufid), 4th grade (2021), 36; Arabic Language (Jadid, Teacher Guide), 4th grade (2021), 220–221 [Audio text].

[18] Indonesia, Islam and Character Education, 12th grade (2018), 248. See also, Eldad J. Pardo and Indri Retno Setyaningrahayu, “Unity in Diversity The Indonesian Curriculum,” (IMPACT-se, 2023).

[19] The Holocaust is briefly but succinctly handled in General History, 11th grade (2018), 90. Other issues related to antisemitism are also taught in the Azerbaijani curriculum. For example, about the Dreyfus Affair, see General History, Grade 11 (2018), 47, 90. About giving respect to Judaism in the Azerbaijani curriculum, see Life Knowledge, 5th grade, (n.d.), 50. This is the textbook currently taught.

[20] Jon Gambrell, “United Arab Emirates Says It Will Teach Holocaust in Schools,” AP, January 9, 2023.

[21] Emrullah Alemdar and Savaş Keleş, Çağdaş Türk ve Dünya Tarihi [Contemporary Turkish and World History] (Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı, 2021), 66–67.

[22] Alemdar and Keleş, Çağdaş Türk, 67.

[23] For more about the portrayal of Israel and Jews in Egyptian textbooks, see Pardo and Winter, “Israel and Jews in Egyptian Textbooks – A Forward-Looking Perspective.” On al-Azhar’s ambivalent voices regarding religious moderation and espousing Hamas views, see Ofir Winter and Michael Barak, “From Moderate Islam to Radical Islam? Al-Azhar Stands with Hamas,” INSS Insight No. 1777, Nov. 2, 2023.

[24] Egypt, Islamic Religious Education, 5th grade, Vol. 2 (2021–2022), 11–18. For a full analysis and translation of the example, see Winter, “Generational Change: Egypt’s Quest,” 59‒60.

[25] See Yonatan Negev and Ofir Winter, “Between Conservatism and Reforms: The Dual Nature of Al-Azhar’s School Curriculum,” (IMPACT-se, November 2023).

[26] Egypt, Christian Religious Education, 7th grade (2022–2023), 47.

[27] Saudi Arabia, Geography, Grades 10–12 (Pathways System—Third Year) (2022–23), 198, 221. See IMPACT-se, Saudi Textbooks 2022–23, Updated Review (May 2023), 95, 109.

[28]“Saudi Arabia Calmly Changes Its Textbooks …Could That Lead to Accepting Israel?” CNN Arabic, June 20, 2023;“Ali al-Nuaimi’s New Disgrace,” Alsyasiah, March 23, 2023; Ahmad al-Fakhrani, “Despite the Effacing of the Palestinian Cause in Egyptian Curricula, Palestine Is Alive In the Hearts of the New Generation,” Raseef22, November 1, 2023.

[29] “Bahrain to Suspend Changes to Curriculum Linked to Israel, Normalization,” Al Arabiya News English, May 11, 2023.

[30] About the PA, see IMPACT-se, “The 2020–21 Palestinian School Curriculum Grades 1–12,” (May 2021). For Jordan, see Eldad Pardo and Maya Jacobi, “Jordan’s New Curriculum: The Challenge of Radicalism,” (IMPACT-se, August 2019), as well as the forthcoming IMPACT-se Jordan report. For Hamas, see IMPACT-se Staff, “Al-Fateh – The Hamas Web Magazine for Children.” About Syria, see Eldad Pardo and Maya Jacobi, “Syrian National Identity: Reformulating School Textbooks During the Civil War,” (IMPACT-se, July 2018). For the Houthi curriculum in Yemen, see Itam Shalev, “Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen 2015–19,” (IMPACT-se, March 2021). Regarding Iraq, see Ofra Benjio, “Clashing Narratives and Identities in Iraq’s School Curriculum 2015–2022,” (IMPACT-se, March 2024). For Iran, see Eldad J. Pardo, “Iran’s Radical Education: An Interim Update Report, 2021–22,” (IMPACT-se, August 2022).

[31] PA, Islamic Education, 5th grade, Vol. 2 (2020–21), 65–66; IMPACT-se, “The 2020–21 Palestinian School Curriculum,” 26.

[32] Syria, Historical Issues, 10th grade (2017–18), 107. For the deceptive nature of Jews in Syrian Islamic Education, see Islamic Education, 6th grade (2017–18), 126–127.

[33] Syria, Arabic Language, 9th grade, Vol. 1 (2017–18), 101.

[34] The Houthi slogan, “death to Israel, curse on the Jews,” is repeated throughout the materials, further reinforcing the message. See example 13 in Shalev, “Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen,” 26. On cursing the Sunnis in Shiite religious thought, see Negev, “Cursing the Companions.”

[35] See Pardo, “Iran’s Radical Education,” 94.

[36] For full analysis of the example, see IMPACT-se, “The 2020-21 Palestinian School Curriculum,” 22–23.

[37] Syria, National Education, 8th grade (2017–18), 61.

[38] See Pardo and Jacobi, “Syrian National Identity,” 73ff.

[39] Pardo, “Iran’s Radical Education,” 70.

[40] For a full translation and analysis of the example, see Pardo, “Iran’s Radical Education,” 108.

[41] PA, Islamic Education, Vol. 1, 10th grade (2020), 72. For full analysis of the example, see IMPACT-se, “The 2020-21 Palestinian School Curriculum,” 9, 12, 25.

[42] Jordan, National and Civic Education, 10th grade, Vol. 2 (2023–24), 34. See also TOI Staff, “Jordanian School Textbook Said to Paint October 7 Atrocities in Positive Light,” Times of Israel, February 3, 2024.

[43]Saraya, “Removal of a Paragraph from the ‘National Education’ Textbook Mentioning the October 7 Events,” Saraya News, February 22, 2024.

[44] Eldad J. Pardo, “Understanding Qatari Ambition The Curriculum 2016–20,” (IMPACT-se, June 2021).

[45] Qatar, Social Studies, 12th grade Vol. 1 (2017) (Advanced), 95. Similarly, “Hatred of Jews; For They Are the Reason for Germany’s Defeat,” Qatar, History, 11th grade, Vol. 2 (2020), 175.

[46] See example 66 in IMPACT-se, “Review of Changes and Remaining Problematic Content in 2021–2022 Qatari Textbooks Annual Report (Fall & Spring Editions),” (July 2022), 71; Qatar, Islamic Education, 11th grade, Vol. 1 (2021–2022), 147.

[47] IMPACT-se, “Review of Changes,” 2‒5.

[48] Syria, National Education, 12th grade (2017–18), 54.

[49] Iran, Sociology 3, 12th grade, Literature and Humanities (2021–22), 88; Pardo, “Iran’s Radical Education,” 90.

[50] Jordan, History of Jordan, 12th grade (2018), 63–65; Pardo and Jacobi, “Jordan’s New Curriculum,” 89.

[51] Qatar, Social Studies, 12th grade, Vol. 1 (Advanced) (2017–2018), 95, 114.

[52] Qatar, Social Studies, 11th grade, Vol. 2 (Advanced) (2017), 32.

[53] See, for instance, the order to halt textbook changes following backlash from opposition in Gulf News Report, “Bahrain Halts Controversial Curriculum Changes Amid Concerns Over National Values and Religion,” May 14, 2023.