Publications

INSS Insight No. 1379, September 6, 2020

The decision by the United Arab Emirates to sign an agreement toward normalization with Israel was hailed by Egypt, Oman, Bahrain, and Mauritania. It was severely criticized, however, by Islamist forces and the Palestinian Authority, which accused the UAE of deviating from the Arab and Islamic line. While most of the discourse in Israel is centered on the political, security, and economic interests affected by the groundbreaking agreement, less attention has been paid to the normative-religious challenge involved in legitimizing it. The polemic between the UAE and its adversaries about the religious legitimacy of the agreement with Israel demonstrates the flexibility of Islamic religious law, and its ability to play a positive role in mustering broad-based public support for peace and normalization among Arab and Islamic audiences. The importance of the religious aspects, as seen by Abu Dhabi, should also be taken into account by policymakers in Jerusalem.

For many years, and particularly over the last decade, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has striven to disseminate a religious-political doctrine that defines peace as an Islamic value and a fundamental element of national identity. It poses this stance as an ideological alternative to the radical concepts of political Islam advocated by the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafi-jihadist forces in the region. Such efforts by the UAE help to foster a national ethos in the country that supports the anti-Islamist vision it seeks to promote in the Middle East. These efforts also contribute to the UAE's international image as a stronghold of religious freedom, pluralism, and multiculturalism.

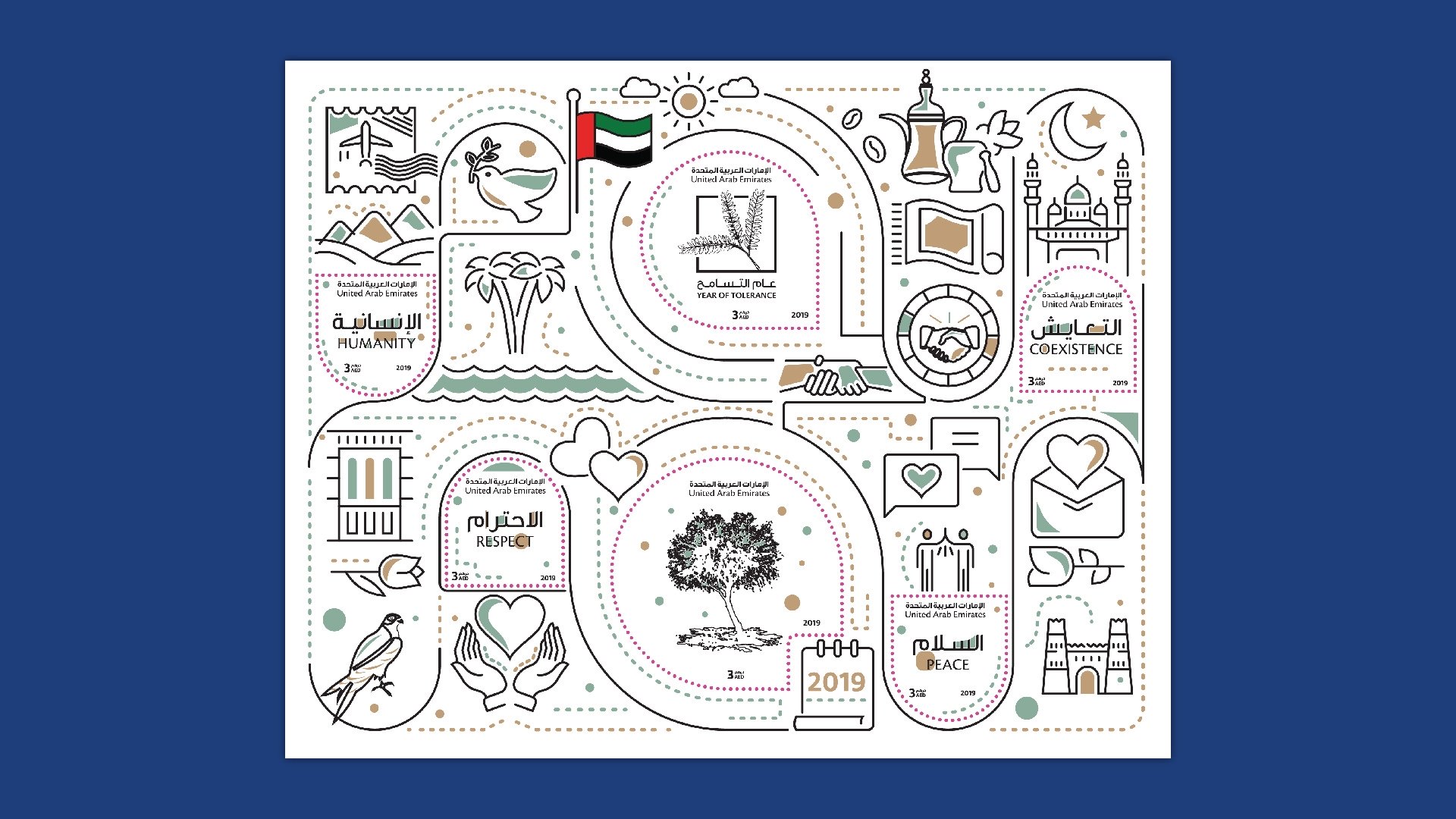

In 2016, the UAE founded a government ministry for promoting tolerance and declared 2019 a Year of Tolerance, during which it hosted a summit between the Pope and Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb, Grand Imam of al-Azhar University, the leading religious authority in Egypt and the Sunni Muslim world. The two religious leaders jointly drew up the Document on Human Fraternity for the express purpose of promoting global peace and coexistence between people of all religions. In 2022, the Abrahamic Family House complex is scheduled to open in Abu Dhabi, and will house a mosque, a church, and a synagogue. The center is designed to promote values shared by the three monotheistic religions, and to promote mutual understanding and acceptance among all believers.

The normalization process between Israel and UAE, under American sponsorship, was fashioned in this reconciliatory spirit, and in part is marketed as a renewed religious rapprochement between Muslims, Jews, and Christians. Those who formulated it named it the Abraham Accord, in honor of the father of the three monotheistic religions. The announcement of the agreement included a section (which is also to be expressed in the agreement itself) stating that all peace-loving Muslims would be allowed to pray at the al-Aqsa Mosque, and that the other holy sites in Jerusalem would be open to peaceful believers of all religions. Official religious institutions and Muslim jurists in the UAE have stamped the accord with their religious approval.

The peace agreements signed by Israel with Egypt and Jordan were also approved by pro-establishment Muslim clerics, who strove to help their regimes achieve legitimacy for the dramatic change in policy and to rebuff Islamist criticism. Yet just as President Sadat and King Hussein were attacked in their countries by the Muslim Brotherhood, which still refuses to recognize Israel, UAE de facto ruler Mohammed bin Zayed is now attacked by the current Islamist axis. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan threatened to close his country's embassy in Abu Dhabi because of the agreement. Iran called it a "knife in the back of all Muslims," while Hamas regards it as betrayal of the struggle of the Palestinian people. The preacher Ahmed al-Raissouni, head of the International Union of Muslim Scholars, which is based in and funded by Qatar, stated, "The prohibition on normalization [with Israel] means a prohibition of theft, occupation, and the other crimes committed and being committed by the Zionists and their country in the past eight decades."

As for criticism in the UAE, opposition members, some of them exiles linked to Qatar, accused the government of breaching Article 12 of the country's constitution, which mandates Arab and Islamic solidarity. They quickly founded an association to combat normalization, and chose a picture of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem as its logo. The association's founding statement concluded with the verse from the Qur’an (5:2), "Cooperate in righteousness and piety, but do not cooperate in sin and aggression." This was designed to highlight what the founders regarded as the contradiction between mandatory support for the Palestinian cause and disgraceful connections with Israel.

The UAE did not shy away from the religious polemic about the agreement's legitimacy. The principal argument cited in the ruling by the Emirates Fatwa Council, the country's supreme religious authority, was that the agreement with Israel is maslaha (literally: an interest), an act that safeguards one or more of the fundamental goals of the sharia (Islamic law). Use of the maslaha mechanism enables the regime in Abu Dhabi to claim that the political achievements of the agreement with Israel also have religious value. Fatwa Council Chairman Sheikh Abdullah bin Bayyah underscored that contracting the agreement was within the exclusive authority of the ruler, once he concluded that it would prevent Israeli sovereignty from being applied to the West Bank, assist a solution to the Palestinian problem, encourage peace, confront the threat of war and pandemics, and benefit humanity.

The UAE also justified its actions by citing Islamic precedents, among them the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah by the Prophet Muhammad with idolaters in Mecca in 628. Bin Bayyah noted that "the Islamic sharia abounds in many examples of such cases of reconciliations and peacemaking in accordance with the public good and circumstances." Just as the opponents of the agreement quoted Qur’an verses, its supporters rely on alternative verses showing Islam's preference for peace, such as, "if they are inclined to peace, make peace with them" (Qur’an 8:61). Dr. Mohammed Matar Salem al-Kaabi, chairman of the UAE General Authority of Islamic Affairs and Endowments, stated that the agreement with Israel was consistent with the principles of Islam, which uphold cooperation between people of all religions, and with the Document on Human Fraternity. He added that the agreement helps reinforce the UAE's international image as a country that champions views of peace and tolerance.

In addition to Islamist attacks, the UAE also faces protests by the Palestinian Authority. Ramallah regards the suspension of Israeli annexation as inadequate compensation for Abu Dhabi's deviation from the Arab Peace Initiative, which made normalization contingent on a settlement with the Palestinians based on the 1967 lines. Jerusalem Mufti Muhammad Hussein ruled that pilgrims from the UAE would not be allowed to pray in the al-Aqsa Mosque. Mahmoud al-Habbash, Supreme PA Qadi and Abu Mazen's advisor on religious affairs, added that any non-Palestinian Muslim coming to pray in the Mosque on the basis of the normalization accord between Israel and UAE was "unwanted in the PA." The PA fears that such visits will help Israel consolidate its image as a country that allows religious freedom, and strengthen its hold on the holy places. The PA's siding with the Islamist axis and against the axis of pragmatic countries, with which it is associated, highlights Ramallah's regional isolation resulting from the agreement and the difficult watershed it approaches.

In response to the Palestinian criticism, Egypt came to the aid of its Emirati ally. Dr. Abbas Shoman, former Secretary-General of the al-Azhar Council of Senior Scholars, denounced the ban on visits by UAE citizens to al-Aqsa, and stated that he knew of no precedent in Islamic law preventing a person, group, or people to pray at any mosque whatsoever because of the political stance of a native country. Shoman wondered why the Palestinians did not bar citizens from Turkey and Qatar from praying in al-Aqsa when their countries had conducted normal relations with Israel for many years in economic and even military matters.

In the case of Oman, the supreme religious authority, which enjoys some independence, did not completely conform to the government's political position, possibly in order to obstruct a potential warming of relations between Oman and Israel. Despite Oman's public support for the UAE's action, Oman Grand Mufti Sheikh Ahmad al-Khalili issued a religious ruling against the emerging agreement, and described a visit to al-Aqsa as unacceptable normalization. He stated that the liberation of al-Aqsa and the liberation of the land around the mosque is a holy duty for the entire Muslim nation.

Significance

The Islamic religion plays a key role in political discourse in the Arab world, in part as a means for the authorities to gain popular support for the prevailing social and political order and for the regime policies. Arab leaders utilize state-funded religious institutions to forestall Islamist opposition and prepare the ground for political measures that arouse internal and external controversy. The question of relations with Israel sheds additional light on the status of the religious establishments in each country, and on the nature of the respective connections between religion and politics. Furthermore, it exposes the profound schism in the current Arab and Muslim world between the pragmatic axis, centered in Egypt, Jordan, UAE, and Saudi Arabia, and the radical axes, led by Turkey and Iran.

The argument between the two sides demonstrates that Islam as a religion has no consensual stance on peace and normalization with Israel. On the contrary, competing actors in the Arab and Islamic world have different and sometimes contradictory views on the issue, and each demands a monopoly on interpretation of the religious canon according to its particular needs and political outlooks. The importance of the religious polemic in legitimizing relations with Israel results from the great weight of Islam as a source of political legitimacy in religious Muslim majority societies. In addition, the Islamic justifications for peace were designed to alleviate the cognitive dissonance involved in the transition from years of conflict with Israel, accompanied by religious tension, to overt formal relations.

The competing regional axes represent distinct political, ideological, and philosophical models: tolerance versus extremism, nationalism versus transnationalism, and pragmatism versus radicalism. Israel has an interest in encouraging the pragmatic axis that supports peace and normalization, and in the weakening of radical ideas that condemn these options. The desired benefits of the agreement between Israel and UAE were described as maslaha, giving them religious validation, but they reflect concrete aspirations: political, economic, and others. To the extent that these aspirations materialize and contribute to the countries and peoples in the region, the political and religious legitimacy of peace with Israel will grow over the counter arguments.

Finally, the agreement highlights the gap between the importance of religious aspects in the discourse coming from UAE and their marginal status in Israeli discourse. Government, civil, and religious actors in Israel should step into this vacuum and take advantage of the positive potential in the interfaith aspect of relations with UAE. The Holy Basin in Jerusalem was explicitly mentioned in the agreement, and an inclusive vision should be fostered around it in cooperation with the peace countries (with an emphasis on Jordan), and, if possible, with the PA.