Publications

INSS Insight No. 1572, March 14, 2022

The World Youth Forum that met in January 2022 in Sharm el-Sheikh was cast in Egypt as preparation for the UN Conference on Climate Change that will be held there in November. At a session devoted to environmental issues, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi declared that “Man is the only creature on earth that is capable of bringing destruction but is also capable of building and repairing.” Indeed, the Forum showed that Egypt seeks to play a leading role in building and repairing, both in its own territory and in the regional arena – Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. Israel, for its part, should support Egypt’s intentions and seek to collaborate with it, particularly in the field of renewable energy.

In recent years the climate issue has occupied a prominent position in the political and public discourse in Egypt. In 2015 Egypt established the National Council for Climate Change as the body responsible for formulating an overall strategy and coordinating government efforts on this issue, and subsequently updated the Council’s composition and authority. In 2016 Egypt published a document of its vision for 2030, which centered on the objectives of reduced air pollution, green energy and clean transportation, treatment of waste water, and protection of biodiversity. In 2020 Egypt launched a center for excellence in environmental studies, designed to position it at the forefront of the global investigation of climate change, and issued green bonds worth $750 million to raise funds for environmental projects. At the climate conference in Glasgow in November 2021, Egypt presented its latest national strategy for dealing with climate change up to 2050, intended for the country’s internal development efforts to match international environmental protocols.

The intense Egyptian activity on the climate issue derives from four considerations: first, the direct threat posed to Egypt by the climate crisis. At the World Youth Forum (WYF) in January 2022, Egyptian Prime Minister Moustafa Madbouly noted that Egypt was one of the most vulnerable countries to global warming, although its contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions is only 0.6 percent. The rises in temperatures and sea levels threaten the coastal areas home to 22 percent of Egypt’s population, its main tourism sites, and agricultural land in the Nile Delta. Climate damage is likely to lead to poverty, waves of migration, and political instability. The overall financial damage the country expects to suffer in the coming decades as a result of the climate crisis is estimated by the Egyptian Center for Strategic Studies (ECSS) at 100-500 billion Egyptian pounds.

Second, Egypt sees itself as the representative of developing countries, particularly in Africa, since it leads the continent in dealing with climate damage and has considerable experience organizing international conferences. By hosting the climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh this coming November, Egypt wants to place itself and the other African countries at the top of the world agenda and recruit the international community to help them by means of grants and loans, investment in green technology, and technological know-how. As they see it, only massive external aid can ensure that less developed countries will be able to play their part in the global effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Third, Egypt’s leading role in coping with the climate crisis is used by Cairo as a diplomatic tool to nurture its soft power. Egypt seeks to use the environmental issue – which has become acute in recent years – to position itself as a constructive player in the eyes of the West in general, and the United States in particular, to establish its regional leadership, and to mark itself as an attractive destination for capital investment in green projects. Indeed, many of the speakers at the WYF praised Egypt for “setting an example” and “leading the way” on environmental issues. The value attributed to Egypt on environmental issues reinforces international concern for its stability and creates positive branding, which to some degree balances criticisms from the West of its human rights record.

Fourth, Egypt wants to contribute directly to the global fight against the climate and energy crises by becoming a hub for gas in the short term and renewable energies in the mid-to-long term, particularly for countries in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. At the WYF, el-Sisi declared that every crisis offers an opportunity, and expressed his hope that Egypt would be a source of cheap and clean energy for Europe through its connection with the electrical networks of Greece and Cyprus, and for its other neighbors, including Sudan, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel. Madbouly added that renewable energy should be the source of 20 percent of the country’s energy in 2022, and 42 percent in 2035. Also at the WYF, Minister of Electricity and Renewable Energy Muhammad Shaker estimated that the cost of solar power and wind power was becoming more competitive, thanks to technological developments enabling this energy to be stored.

Egypt has a string of flagship ventures in the field of green energy: the Benban Solar Park in the Aswan district, the largest of its kind in the Middle East and one of the largest in the world, produces more electricity than the Aswan Dam; the wind turbines at Ras Ragheb and Jabal al-Zayt supply clean electricity to about a million families; the nuclear power station at el-Dabaa is due to start operating in 2028 and by 2035 to supply 3 percent of all energy in Egypt; green cities, headed by the new administrative capital, will rely on renewable energy; and there are ventures to produce green hydrogen for industry, to convert automobiles from petrol to gas, and to produce electrical vehicles.

The Potential for Egyptian-Israeli Cooperation

The climate crisis presents humanity with a worldwide challenge that requires countries and peoples to join forces, and this is certainly true for Egypt and Israel, who share a similar climate and therefore face similar challenge. These include utilizing green energy, preventing sea and land contamination, preventing flooding of coastal towns caused by rising sea levels, protecting bio-diversity on land and at sea, ensuring water and food security, stopping desertification, and dealing with natural disasters such as floods and fires. Egypt’s moves to encourage joint regional activity with neighboring countries on climate issues, as expressed at the World Youth Forum, are in line with Israeli policy and create a basis for intensifying and expanding the links between Cairo and Jerusalem.

In recent years natural gas has helped warm relations between Israel and Egypt: Egypt supplied Israel with a destination for natural gas exports and liquefaction facilities, while Israel supplied Egypt with an additional source of gas and supported its positioning as a regional energy hub, and the establishment of the Cairo-led East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF). Israeli gas is expected to continue flowing to Egypt at least until the end of the decade, and both countries have an interest in anchoring its status as an “interim station” in the move from coal to cleaner energy. In the short term, Israeli export of gas to Egypt is even expected to grow, given the escalating energy crisis in Europe following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. At the same time, in view of the global trend for increased reliance on renewable energy, it appears that the use of gas may decline in the medium and long term, and both countries must already start making joint preparations for the post-fossil fuels era.

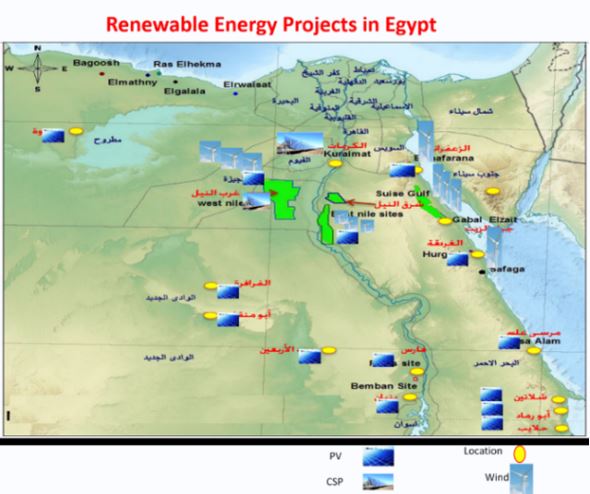

Continued fruitful cooperation in the field of energy, therefore, requires Israel and Egypt to diversify their connections and work on renewable energy in addition to gas. In this field there is also promising potential for synergy: both countries have set themselves a goal for the coming years of investing in the accelerated development of renewable energy sources. Israel has special technological know-how, while Egypt has well developed infrastructures, large areas for placing solar panels, and an ambitious vision of connecting regional energy networks. In the Sinai Peninsula, for example, there are as yet no significant projects in the field of renewable energy. Future projects there could serve Egypt, Israel, and the Gaza Strip (see map), and organizations such as the EMGF, the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM), and the International Energy Agency could provide a platform to promote them.

Source: Egyptian Ministry of Electricity & Renewable Energy

Israel’s participation for the first time in the Egypt Petroleum Show held in February in Cairo is an additional sign of positive movement in the bilateral relations. Minister of Energy Karine Elharrar led the Israeli delegation, and received a special personal welcome from President el-Sisi, who went over to greet her in a live television broadcast. This gesture reflects the President’s recognition of Israel’s role in strengthening Egypt’s status as a regional energy hub and his willingness to display openly the strengthening ties between the states in the gas realm.

At the closing ceremony of the WYF, President el-Sisi announced the encouragement of dialogue between groups of young people from Egypt and other countries in preparation for the climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh. Last February, Israeli Minister for Environmental Protection Tamar Zandberg also mentioned the conference as an opportunity to strengthen regional collaboration, and noted that she is working with her Egyptian counterpart, Yasmine Fouad, to establish a regional climate forum for Middle Eastern countries.

While Egypt has been preoccupied with climate issues for several years, Israel is trying to catch up with the world in this context by formulating an overall strategy and setting long term targets. Both sides will gain from encouraging dialogue between government agencies, civil society, experts, and young people, in order to shape a coordinated environmental vision and policies that will meet their common needs.

* This article was written in the framework of the INSS research program on Climate Change and National Security, supported by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS) in Israel. The author wishes to thank Dr. Moshe Terdiman and Dr. Shira Efron for their constructive comments.