Publications

Special Publication, January 5, 2023

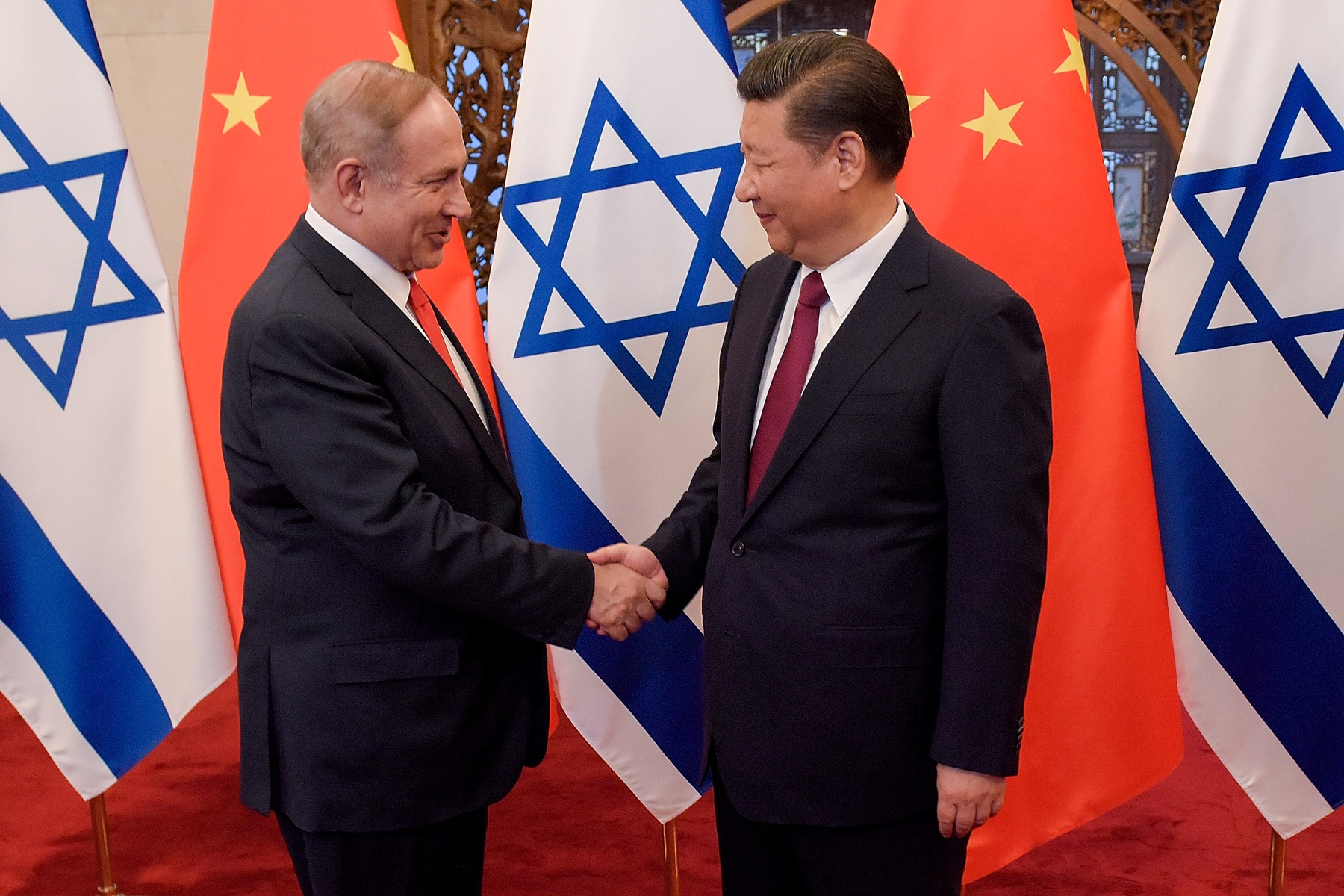

As the 37th Israeli government begins its term of office, it faces a host of national security challenges, from the Temple Mount, to the Palestinian theater, the security challenges in the north, and the complex threat from Iran, most of which have a significant international dimension. Against the background of the strategic competition between the great powers, the war in Ukraine, and the struggle for technological-economic dominance, the new government must navigate prudently between the United States, Israel’s great strategic ally; and China, its significant economic partner, Russia, its military neighbor in the north; and other important countries in Asia and Europe. Benjamin Netanyahu is returning to the Prime Minister’s office and to the management of Israel’s relations with the powers at a time of many reversals and upheavals. The man who over the past decade enthusiastically campioned the development of Israel’s relations with China must chart Israel’s future path – between China and the United States, and between the economy and national security.

As a rule, the contours of Israel-China relations have been shaped in the shadow of United States relations with China: during the Cold War, Israel was primarily part of the Western bloc; in the 1970s, when the United States sought to establish relations with Beijing, Israel’s defense support to China began with Washington’s blessing; in 1992, after the fall of the Soviet Union and the Madrid Conference, Israel and China established diplomatic relations; following military tensions between the United States and China at the end of the 1990s and the Phalcon and Harpy crises with the United States, Israel stopped its defense exports to China; after 2001, as the United States focused on the war on terror and the Middle East, Israel-China economic relations blossomed. Washington has since woken up to the challenges from the East, and the ripples have reached Israel’s shores.

Since early last decade, Israel’s governments have pursued a clear policy of promoting economic relations with China – in innovation, investment, projects, and trade. PM Benjamin Netanyahu, the architect of these relations in these years, identified China’s growing economy as an important opportunity for Israel, defining the start-up nation’s innovation as an excellent match for China’s technological needs, capital, and markets as a “marriage made in heaven.” In his new memoir, Bibi: My Story, Netanyahu describes the policy: “Like most Western leaders, I walked a fine line with China. On the one hand, I wanted to open the enormous Chinese market to Israel and also lure Chinese investments to Israel, particularly in physical infrastructure. On the other, I was totally frank about setting clear limitations on what types of technologies we would share with China, stopping when it came to military and intelligence fields. This was our solemn commitment to our great ally the United States, with whom we shared much of this technology, as well as our cherished values as democratic societies.”

Indeed, Israel’s policy on its relations with China in this period, shaped by resolutions taken in 2013-2014 (155, 251, 1687) and focused on seizing opportunities, was driven from 2014 onwards by the joint Innovation Committee and formalized in the Comprehensive Innovative Partnership agreement, signed in March 2017. In those years the volume of trade in commodities with China rose (from about $9 billion in 2012 to about $18 billion in 2021; by November 2022 annual trade in goods passed the $19 billion mark); Chinese investments in Israel increased, as has Chinese involvement in Israeli infrastructure projects, mainly in the areas of transport, energy, and water. Then-Minister of Transport Israel Katz worked energetically and with determination to promote Israel’s infrastructure and transport needs with Chinese involvement, with the emphasis on ports, railways, and public transport. Israel’s policy on relations with China during this period sought to maximize economic relations, with the emphasis on innovation, to the exclusion of the military-defense realm.

Source: Glazer Center for Israel-China Policy

Source: Glazer Center for Israel-China Policy

In December 2017 the Trump administration published its National Security Strategy, with competition with China as the main priority and technology at its core. In the following years, Washington stepped up the pressure on Jerusalem to limit its relations with China in areas affecting national security, particularly investment, infrastructures, communications, data, and technology. Under this pressure, in late 2019, the Netanyahu government passed a resolution (372b) to set up an advisory mechanism on the national security aspects of foreign investments in areas subject to regulation, though not in the area of technology. The resolution, which does not mention China, reflects a development in Israeli policy – widening the exclusions in its economic relations from a narrow security scope (military and defense) to broader definitions of national security, somewhat in response to the demands from Washington. Nonetheless, many in Israel and the United States described this policy as “walking between the raindrops,” seeking to minimize the restrictions, gain time, and navigate between the US demands, Israel’s economic needs, and their advancement in China.

Ostensibly, the 36th Israeli government led by PM Naftali Bennett and the caretaker government led by PM Yair Lapid continued the policy of their predecessors on relations with China. During their premierships the Israel-China Joint Innovation Committee met, marking 30 years of diplomatic relations between the countries; SIPG from Shanghai began to operate the Bay Port in Haifa; and work continued on the Red Line of the Tel Aviv Light Railway – two projects with Chinese involvement that began during Netanyahu governments.

In fact, however, recent years have seen a quiet change of policy over Israel’s relations with China, stemming from its relations with the US. Before Prime Minister Bennett left for his first meeting with President Biden, his office briefed that the Israeli government took American concerns about relations with China very seriously, and saw them as a national security issue. On the eve of President Joe Biden’s visit to Israel, on July 13, 2022, the President and Prime Minister Yair Lapid published a joint statement on the launch of a strategic dialogue on advanced technologies, and since then two meetings were held in Washington (August 23 and September 28), headed by National Security Advisors Jake Sullivan and Eyal Hulata. In the framework of the dialogue, work groups were set up headed by the Ministries of Science, Health, and the Environment, on artificial intelligence and quantum, pandemics, and climate, respectively, on the one hand, as well as a work group headed by National Security Staffs on Trusted Tech Ecosystems. This statement does not mention China, although the agenda of the last working group reflects US national security concerns over China in the technological dimension.

On October 12, 2022, the Biden administration published its National Security Strategy; China remains at the top of the list of challenges, with technology occupying a central position. By chance, on the same day the Israeli government passed a resolution (41b) to strengthen the advisory mechanism on foreign investments, which doesn’t mention China. In an interview in Haaretz (December 18), US Ambassador to Israel Tom Nides said the administration has reached understandings with Israel regarding trade with China as well, and will tighten oversight of the sale of local technology to the East Asian giant, due to concerns that the technology will reach the wrong hands. “We can’t tell Israel with whom to trade, nor will we. We just want to make sure that there are checks and balances to make sure that they understand where the technology might end up,” he said.

Israel’s policy during this period has therefore sought to promote fruitful and secure economic relations with China, albeit with growing control and under wider restrictions, while strengthening its strategic partnership with the United States, with the emphasis on technology and innovation. Senior administration officials in Washington have recently expressed appreciation of Israel’s considerable progress in this area (“Israel scores very high”), mentioning the clear change under the outgoing government, and looking forward to a continuation of this progress under the next government.

Israel’s relations with China reflect a complex trend. An analysis of economic data shows that while the volume of trade in goods is steadily increasing, exports from Israel to China peaked in 2018, as did the number of Chinese investments in Israel, and both have declined since then. Yearly trade in goods with China until November 2022 approached the scope of trade with the United States ($19.22 and $20.23 billion, respectively), about half the volume of trade with Europe, but in the field of services from Israel, exports to China are only about 1 percent of the exports to the US, which are worth some $17 billion (2020). China’s involvement in infrastructure projects peaked in 2019, and has since fallen sharply. Chinese companies lost a number of prominent infrastructure tenders and there was also a decline in their bids for tenders. Flights and tourism between Israel and China were limited during the pandemic years, and are only now being cautiously renewed. Even public opinion on China in Israel, which in the past was very positive, has dropped by about 20 percent, as in many Western countries. These developments are an outcome not only of Israeli government policy; rather, they primarily reflect global developments in economy and foreign relations, particularly the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and disruption of supply chains, as well as Chinese policy, for example in the field of capital outflow, Beijing’s Covid policy, and United States policy on technology and chips.

Source: Glazer Center for Israel-China Policy

Source: Glazer Center for Israel-China Policy

What kind of policy will Benjamin Netanyahu lead as he returns to the Prime Minister’s office? The honeymoon of the previous decade’s “marriage made in heaven” is over, and in any case this conjugal metaphor never suited interest-based interstate relations, which are rarely exclusive. In an interview with Bari Weiss, Netanyahu was asked about Israel’s relations with China, and whether they were a substitute for a United States that is receding in on itself and whose support for Israel might dwindle. His reply, which was no doubt aimed largely at the American public, contained indications of his future policy. First, he stressed the United States as Israel’s indispensable ally and as the world’s beacon of liberty. Second, he stated that Israel, like all countries, needs alliances, but there is a difference between its relations with sister democracies in the West, and above all the United States, where the ties are deep and based on shared values, and relations with other countries. Third, “there is a limit to how much we can open ourselves up to being dependent on non-like-minded states. We're all drawing the lessons from that with the supply chain issues during Covid.” Therefore, he said, “I enthusiastically opened Israel up for trade with China and economic enterprises with China. I suppose I'll continue to do that. But matters of national security are also uppermost in our minds as they are in the minds of others. We'll continue to work with China, but we'll also protect our national interests.” Interestingly, in his speech to the Knesset at the swearing in of his new government, Netanyahu vowed to develop a high-speed train connecting Israel’s north to Eilat in the south. Notably, Netanyahu has previously tried to advance a project on a train to Eilat with China’s involvement. Does he intend to try this again?

The world as it was when Prime Minister Netanyahu shaped his policy early last decade has changed entirely. Competition between the great powers is fiercer and has spilled over from exchanges of blows and tarriffs to dramatic restrictions on exports of silicon chips and technology, to a war in Ukraine and to the real possibility of a military clash over Taiwan. Netanyahu can’t enter the same river twice, when Israel’s room for maneuver between the powers, particularly on technology, has shrunk significantly. Many Western countries face dilemmas similar to those facing Israel, and are part of an emerging camp for technology partnerships between democracies. In view of the range of political issues on the agenda between Jerusalem and Washington – Iran, the Palestinians, Russia and Ukraine, and numerous domestic matters – relations with China appear to be a subject where the government has neither need of nor interest in a confrontation with Washington, for whom China is a major concern.

The government of Israel must be aware of differences in the degree of urgency in Jerusalem and Washington on China, and to the United States’ sensitivity over the tempo and direction of Israel’s progress on this front. The strategic dialogue with the United States opens up new horizons for Israel for breakthrough collaborations with its greatest ally, and enables it to increase its value for Washington and to strengthen the strategic ties between them. The new Israeli government should continue building its policy on the layers sown by its predecessors since 2019: to continue to advance economic relations with China under national security considerations; continue to decrease its exposure to the national security challenges associated with China worldwide: dependence, espionage and influence, supply chain security, and loss of technology; and promote the strategic dialogue with Washington on trusted tech ecosystems, as a path toward improving the security of Israel’s technologies in the face of external challenges, and strengthening relations with its indispensable ally.