Publications

A Special Publication in cooperation between INSS and the Institute for the Study of Intelligence Methodology at the Israel Intelligence Heritage Commemoration Center (IICC), November 13, 2024

This article addresses the phenomenon of Iranian foreign interference in social media platforms in Israel during the years 2020–2022. Its aim is to examine and characterize the phenomenon, discuss its consequences, and propose policy addressing it. The study reveals that agents of foreign interference in the discourse on Israeli social networks do not favor a certain group or agenda in Israeli society; rather, they aim to deepen the rifts in Israeli society and weaken it. The article begins with a description of the main operations present in the Israeli discourse in recent years. We then present an analysis of the phenomenon and identify the main modus operandi of the perpetrators. Finally, we provide policy recommendations for the government, civil society, and the public.

Introduction

In the digital era, social networks have become the new “digital town square” active both in routine times and during emergencies. Over 70% of the Israeli public uses social networks for various purposes: consuming information, expressing diverse opinions, receiving purchasing recommendations, and staying in touch with friends.[1] However, it is not just Israeli citizens who use social networks in Israel. Occasionally, social media accounts that appear “Israeli” and publish content aimed at the Israeli public are, in fact, operated by hostile entities intending to interfere with and disrupt Israeli discourse in order to advance their strategic goals.

This study provides an in-depth analysis of foreign interference operations carried out on social networks in Israel in recent years, specifically from 2020 through the end of 2022. The study aims to analyze and characterize this phenomenon, discuss its implications, and propose policy recommendations to address it. Findings reveal that foreign actors engaging in Israeli social media discourse do not necessarily support any specific group or agenda within Israeli society. Rather, their primary objective is to deepen societal divisions and undermine the country's stability. While Iran is identified as being behind most of the influence operations discussed in this study, recent evidence suggests the involvement of additional actors.

The following research questions were examined:

- What are the modus operandi of foreign interference operations on social networks?

- How can suspected inauthentic activity on social networks be linked to foreign influence agents?

- What can we learn from the handling of the digital platform and the government that were exposed?

- What insights can be drawn from how digital platforms and government entities handle these exposures?

- How do networks affect national security, democracy, and national resilience?

- How do such influence networks affect national security, democratic processes, and societal resilience?

Part 1. Description of the Foreign Interference Operations

The foreign interference operations examined in this study were carried out by social media accounts exhibiting inauthentic behavior and were likely operated by foreign state actors. Later in the document we will detail the criteria used to identify each account as inauthentic, foreign, or Iranian. A report published by Meta discussing influence operations that took place during the years 2017–2020,[2] defined influence operations as “coordinated efforts to manipulate or disrupt the public discourse for a strategic goal.”

In this study, we focused on three groups of interference operations targeting specific audiences in Israel from early 2020 until the end of 2022. Additionally, we included networks active around the November 2022 election campaign.

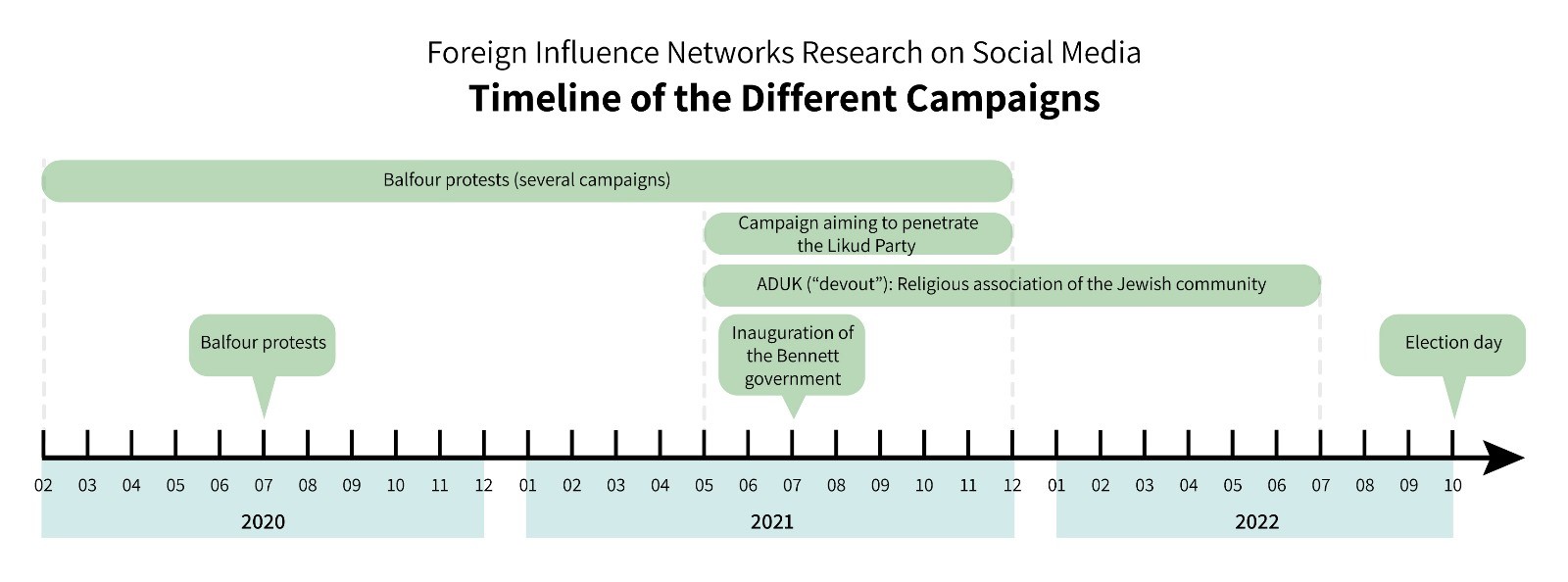

Figure 1. Timeline of Foreign Interference on Social Networks in Israel Included in This Study and Main Events in Israel During This Period

Influence Campaigns by Groups Posing as Activists in the Balfour Protests (February 2020–December 2021)

In this category, we include at least five influence operations and their affiliated accounts that were identified by Facebook and FakeReporter, which all shared similarities in terms of content and patterns of activity. The common denominator was posing as groups of activists from the Balfour protests (such as the legitimate groups of “The Black Flags” (haDegelim haShchorim in Hebrew) and “No Way” (ein matzav) groups). The operations took place from the beginning of 2020 until the end of 2021. The documentation about these groups is extremely limited, as Facebook shared information about these groups in its publications only after it had removed their accounts. Those behind these interference operations had access to a variety of platforms and tools at their disposal, including accounts on Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Twitter, websites, Facebook groups, and Telegram channels. The various operations employed multiple tactics and methods, including both Hebrew and English language accounts, impersonation of legitimate protest organizations and private individuals, and tagging tens of thousands of Instagram accounts.

The first operation—Black Flags IL—was identified by Facebook and disclosed in a report published by Meta in November 2020.[3] Facebook removed the accounts that were part of the operation, stating that Iranian agents were behind them. According to the report by Meta, a total of 12 Facebook accounts, 2 Facebook pages, and 307 Instagram accounts were identified as part of this single operation. About 1,100 accounts followed one or more of the pages, and about 9,500 people followed one or more Instagram accounts related to the operation.

A report by Graphika claimed that the operation did not allocate significant resources to creating these accounts. For example, the names “Leah” and “Ori” were selected for a dozen accounts in the operation. Instagram accounts were created with a standardized format of full name and year of birth. In addition, no effort was made to select credible profile pictures; rather, they used pictures from the Getty Images database (which included the company’s watermark) or used profile pictures of Arab women wearing hijab in accounts bearing Hebrew names.[4]

Facebook stated that when it removed the accounts, those behind the operation were still in the initial stages of building their community of followers. The operation used fake accounts, most of which had been created around the same time. Over time, these accounts changed their names and worked to promote various goals that served the aims of the Iranian influence operations. The accounts published pictures, memes, and content in Hebrew and Arabic. In some cases, different accounts published identical content, such as the same picture. The content revolved around current events, including anti-Netanyahu demonstrations and criticism of his policy on the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to Graphika’s report, the content changed at each stage of activity. The content addressed various issues based on public discourse in Israel and aimed to create social or political divisions. In the first few months of 2020, after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the content primarily focused on criticizing Netanyahu’s policy in addressing the pandemic. Specifically, it centered on the tensions between the government and its citizens, as well as the significant impact caused by the pandemic. In July of that year, the accounts affiliated with this operation started to publish content associated with the Black Flag movement—a legitimate Israeli protest movement that started during that period to oppose Netanyahu.

According to Graphika’s report, in one case, one account published the details of a PayPal account to which money could be transferred for donations to the operation. According to Facebook, the operators of these accounts attempted to hide their identities, but the company discovered links between them and entities connected to EITRC, an IT company based in Tehran.

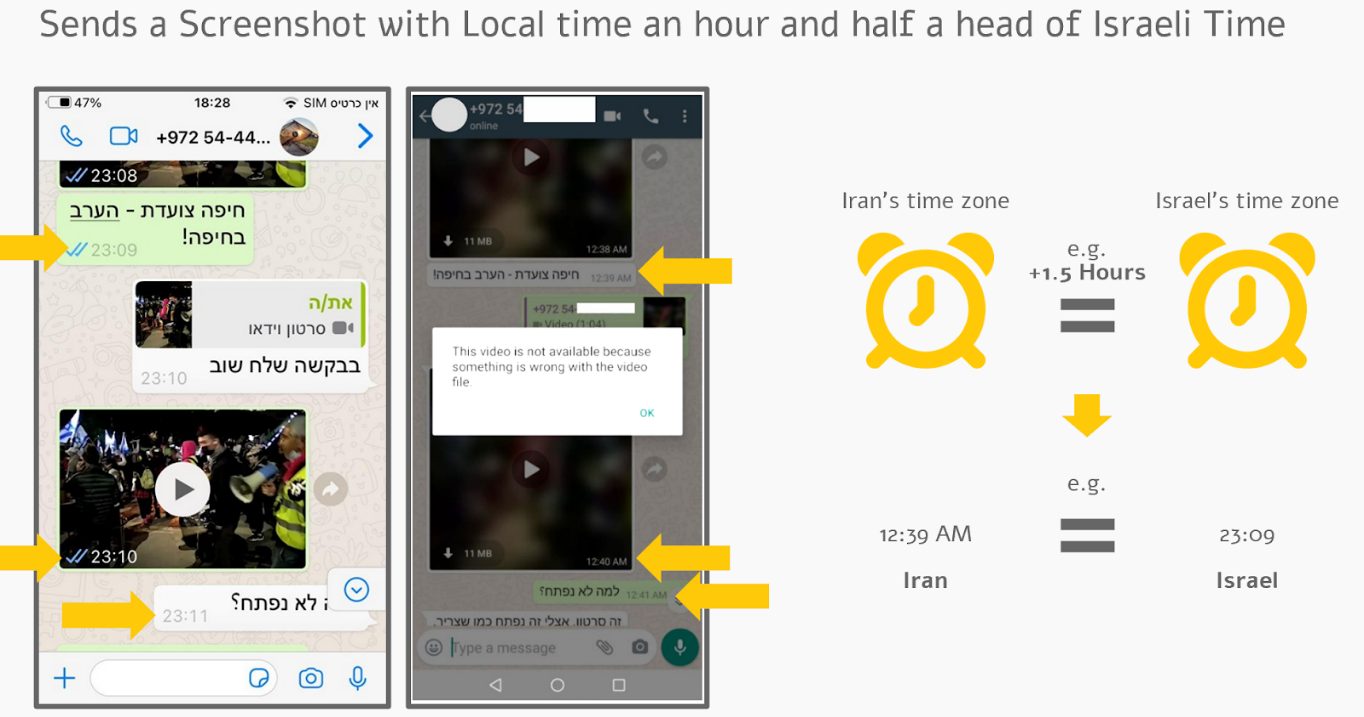

In December 2020, the team that eventually developed into FakeReporter began receiving reports about a suspicious person who joined WhatsApp groups and, in direct conversation with group members, asked for photos from demonstrations in Israel. In exchanges with this individual, indicators emerged connecting him to Iranian entities: broken Hebrew; backward question marks (؟), which are typical of Persian; screenshots from a phone with an interface in Persian; and a 1.5-hour time difference, reflecting the time difference between Israel and Iran (see Figure 2). Moreover, attempts to receive donations from Israeli citizens were identified.

Figure 2. Messages Between an Online Agent who Contacted Activists in the Balfour Protests and an Activist Whose Time Zone Is Characteristic of Iran’s

As part of this operation to impersonate BB (Black Banners) movements, in addition to infiltrating WhatsApp groups and making contact with Israeli citizens, a website was found that posed as part of the Black Flag movement. The pictures shared with the operators and updates on the demonstrations were posted on this website. As part of the operation, three domain names were acquired in November 2020, with names similar to the real “black flags il” movement. Moreover, about 10 accounts affiliated with this operation were set up on social media networks, including an account in Arabic. The accounts followed central activists in the protests. This influence operation was reported on the Kan 11 television channel,[5] and its operators responded in a video that they created, which was posted on the group’s Telegram channel. Following the report on Israeli television, Facebook and Twitter closed the relevant accounts, although one of the websites and the Telegram channel related to this operation are still active.

ADUK (“Devout”)—The Virtual Religious Association for the Religious Community (2020–2021)

The ADUK operation was active on several platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, and a Telegram channel, and posted content with a right-wing orientation related to the Haredi community. Meta confirmed to the BBC that Iranian operators were behind it. The Facebook and Twitter accounts that belonged to the network were closed by the platforms, but its Telegram channel continues to operate.

The name of the operation was ADUK, which was an acronym for “The Virtual Religious Association for the Religious Community.” The operation aimed to promote a Haredi agenda with a right-wing orientation. According to the Telegram channel, the topics discussed included “the voice of the religious community, news in real time, Haredi news in real time, the struggle against violence (police and Arab), anti-secular, interesting questions in Jewish law (Halacha), stories of the righteous.” In particular, the channel made statements against the police as well as claims of the IDF’s incompetence. The channel also addressed issues such as COVID-19 (the operation took place during the peak period of the pandemic), the cost of living in Israel, and so forth. In addition, the operation posted halachic issues under the hashtag (interesting issues in halacha) as well as Shabbat times each week.

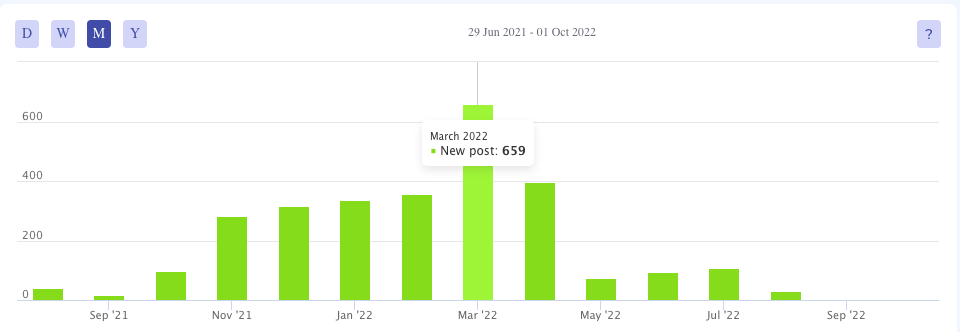

Most of the content posted on the Telegram channel was replicated from real posts made by ultra-Orthodox social media users. Operation ADUK’s Facebook page and group used stolen pictures of a deceased Russian Jewish man. The operation’s other characteristics included copying content from authentic accounts that served the operation’s agenda; creating fake assets to develop authenticity (a logo, the invention of the name ADUK, the creation of a special page as part of creating the fake identity); adding logos to the pictures posted; engaging in incitement, racism, and hate speech; attempting to appeal to emotions; consistently using the same hashtags (#enough is enough, #hot news); and sharing content in groups and channels that appealed to a right-wing and Haredi population. At its peak in March 2022, the operation published over 600 posts on Telegram (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Number of messages published per month on the Telegram channel of ADUK (based on Telemetrio)

It seems that the goal of the ADUK operation was to deepen the divisions and rifts in Israel. ADUK’s Telegram channel had reached 770 followers on March 20, 2022. Although the operators invested in this operation and posted content consistently and systematically, it did not gain widespread exposure and did not have significant influence over the Israeli public.

FakeReporter exposed the operation’s activity on its Twitter account on February 3, 2021.[6] The network was subsequently covered by the BBC,[7] and in response to the reporter’s request for a response from Meta, Meta confirmed that the operators of the accounts were Iranians.

Making Contact With Political Activists Associated With Netanyahu (July 2021–December 2021)

This group of accounts was discovered following a report received in November 2021, according to which a suspicious account had made contact with an Israeli citizen and tried to get her to say things about demonstrations in support of the political right. As a result of the report, approximately ten fake Facebook and Twitter accounts were identified, which had joined about 90 Facebook groups, more than half which were groups of Netanyahu supporters. These accounts posted content mainly against the government, which was then led by Naftali Bennett and tried to inflame tensions in Israel by fueling demonstrations and protest activities.

The fake accounts posted replies to prominent political activists, and they succeeded in making direct contact with some of these activists and received their phone numbers. The fake accounts were connected as virtual friends, amplified messages, sometimes sharing identical content, and they were active at similar times. The fake accounts created original content that aimed, in part, to promote real demonstrations that were held in Israel.

In one case, the operators of these accounts created and shared an invitation to a demonstration in September 2021, in which photographs from the fake accounts were integrated with pictures of real political activists. Afterward, the invitation was shared by political activists in groups connected to the Likud. Various actions taken by these accounts indicate deep familiarity with Israeli political activists.

The accounts that were identified as part of this operation were first opened in July 2021, and in November 2021, initial reports of suspicious activity by these accounts were made. On December 29, 2021, Channel 12 News broadcast a report about the interference operation,[8] after which Facebook and Twitter removed the accounts belonging to this operation.

The Elections to the 25th Knesset in November 2022

During the period of this research, the elections to the 25th Knesset took place in November 2022. At that time, additional operations with similar characteristics were uncovered. They included:

An Operation to Cause a Split in the Knesset List of the Religious Zionism Party.

Prior to the elections, a number of Twitter accounts were created, of which 40 have been identified. All these accounts were opened on August 2, 2022, and used profile photos of men who were employed by the real estate company RE/MAX. The accounts posted copied content, including caricatures and jokes, and did not raise any suspicions until September 14, the day before the submission of the Knesset party lists, when they began posting caricatures of Itamar Ben-Gvir and called for a split in the Religious Zionism Party using the hashtag #run alone in the elections. On October 18, 2022, FakeReporter reported the operation to Twitter and publicized it on its own channels and in Haaretz. On October 19, the accounts were removed.

Voter Suppression Operation on Election Day. Another operation was carried out to suppress voter turnout on election day, and it included two stages with indications that the same entity was behind both stages, based on activity patterns. In the first stage, hundreds of Twitter accounts were opened during a short window of time on October 17, but they did not post content until October 28—three days before the elections. Two days before the elections, these accounts began to coordinate thousands of tweets. The profiles posed as Israeli citizens, mainly opponents of Netanyahu, and called for boycotting the elections. The first group of accounts in the operation was removed before election day, while another group began its activity on election day. On October 31, the day before the elections, FakeReporter reported the operation to Twitter. The first set of profiles was removed on election day.

On election day, the second stage of the operation began. Several hundred Twitter accounts were created on October 22 and operated on election day. This operation also included posts in Arabic and promoted content aimed at suppressing voter turnout. On election day, FakeReporter reported the accounts to Twitter, and they were removed.

After the Elections: The Election Fraud Campaign. A group of accounts that operated on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Telegram made claims about election fraud and nonacceptance of the election results and called for a protest in front of the Prime Minister’s Office the day after the elections. About 15 accounts operated as part of this operation, and more than a thousand fictitious accounts followed them, apparently to increase the credibility of the main accounts in the operation. This collection of accounts that operated around the Israeli elections underlines the great interest that agents outside of Israel showed toward central events in the country and raises questions about their impact on the integrity of the elections.

Part 2. Shared Characteristics of the Interference Operations

In this section, we will present the modus operandi of the agents managing the interference operations. These pattern can be used to identify future interference operations, and they point to characteristics that require further examination. However, it is important to note that the operators of the interference operations continuously adapt and learn, and some of the characteristics are expected to change. One of the main changes in the past year relates to the accessibility of generative AI technologies, which affects the way influence operations are now waged.

The following is a list of common characteristics in the interference operations under study:

Content Related

- The fictitious accounts that belong to interference operations generally used Hebrew names. These names were intended to cause the Israeli Hebrew-speaking population—the target audience of the operations—to believe that these were authentic accounts belonging to real people and not fictitious accounts with foreign interference agents behind them.

- The profile pictures that were used in the interference operations were mainly stolen images or photos of unknown origin. Additionally, in some cases, pictures from stock photo databases; selfies in which it is difficult to identify the people photographed because the faces were hidden by the telephone; and photos of porn actresses that had been distorted making it impossible to locate their source were all used as profile photos.

- The accounts belonging to the interference operations often responded to posts about current events in Israel. In this way, they increased their credibility as Israelis who were knowledgeable about events in their country, were involved in the issues at the center of the local discourse, and received greater attention.

- In many cases the content posted on the fictitious accounts was copied from real users; that is, real people (including journalists, prominent tweeters, viral content, posts by news outlets, and so forth).

- The content of the posts addressed controversial issues in Israeli society. The variety of issues discussed indicates that these operations did not have an interest in favoring or acting against certain figures in the political system or in Israeli society but rather sought to identify issues that could deepen rifts in Israeli society and that could arouse intense responses on social networks.

- Many posts were characterized by poor grammar and inarticulate language. Sometimes, original posts were written in broken Hebrew. This stems from the fact that the writers were not native speakers, learned the language from listening, or used an automatic translation engine (such as Google Translate), causing the use of imprecise and incorrect language. In addition, when writing original content in Hebrew, they sometimes used incorrect or inappropriate words.

Relating to the Pattern of Activity of the Accounts in the Operations

- The fictitious accounts belonging to the operations functioned simultaneously on a variety of platforms. For example, accounts with the same name or using the same profile pictures were opened at the same time on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and so forth. This increased the credibility of the fake accounts in the eyes of those interested in checking their authenticity—the greater their internet presence was, and the more investment made in it, the more these accounts gave the impression that real people were behind them.

- The interference operations used frameworks that include groups, communities, and pages created by their operators. The pages and groups were given names of initiatives that represent the operation. Moreover, they created fictitious figures that promoted the content on the groups and pages of the initiatives or operated them.

- It is evident that most operations continued over an extended period. During the period of activity, the accounts that belonged to the operation systematically posted a variety of types of content, gradually building their credibility.

- The fictitious accounts operated in a coordinated manner. For example, they posted things at regular times (during hours of activity that seemed like work shifts).

- The fictitious users in the interference operations were members of popular Facebook groups with diverse political affiliations (for example, “Benjamin Netanyahu the Official Group”) and posted content in them. In this way they succeeded in gaining publicity and exposing an authentic audience to their content.

Part 3. Indicators of Suspicious and Inauthentic Behavior on Social Networks

The following list of characteristics can indicate coordinated, inauthentic activity on the internet. A single characteristic, however, is insufficient for determining with a high level of certainty that an account is not authentic:

- The use of stolen, fake, or AI-based profile pictures, or the inability to identify the figures appearing in them, and so forth

- Publishing content copied from real users (influencers, media outlets, and so forth)

- Repetition and duplication of identical responses to other users (fictitious or real) several times

- Follower-to-following ratios between suspicious accounts—this sometimes makes it possible to identify additional fictitious accounts

- Unusual usernames—for example, ones that only have a first name, or a group of accounts with usernames that have a fixed pattern

- Membership in numerous Facebook groups, most of them on political issues or related to the content areas of the operation

- Creating groups on Facebook and WhatsApp as well as Telegram channels with the name of the activity and aiming to promote the content of the operation

- Posting content at consistent times.

The list of characteristics below differentiate between locally coordinated inauthentic activity and foreign interference. Many of the signs included in this list relate to the use of language and understanding of the cultural-social context, which makes it possible to distinguish between an inauthentic Israeli account and a foreign agent. It is important to note that as artificial intelligence technologies improve, some of these suspicious indicators could disappear. Among them, we can note the following characteristics:

- Errors in Hebrew when writing original content or in correspondence with Israelis

- Backward question marks that can indicate the use of a keyboard in Arabic or Persian

- Repetitive content and sharing controversial and sometimes inflammatory issues.

- Complex systems that operate across multiple platforms over time, backed by significant organization with resources and infrastructure for conducting an influence operation

- Platform confirmations (Facebook, Twitter) that these accounts are operating from outside of Israel. Usually, the platforms will not state the precise source of the activity

- Time difference from Israel (in screenshots for example)

- The use of non-Israeli phone numbers from outside of Israel (for example, from the Palestinian Jawwal network or other area codes that are not +972) for WhatsApp users.

In some cases, evidence makes it possible to determine with a high degree of certainty that an operation is conducted by an Iranian body:

- Screenshots and reports from internal sources (such as Facebook) indicating that the device is set to Iran’s time zone, the interface language is Persian, or confirming the identification of inauthentic networks as part of influence operations active in Israel.

- Linguistic errors in original Hebrew texts characteristic of Persian speakers, as verified by linguistic analysis.

Based on the outlined above, it can be inferred that Iran is behind most of the operations analyzed in this research. The content and nature of the interference operations’ activity suggest that the operators’ primary objective is to intensify internal polarization in Israel by discussing controversial issues and by magnifying and exaggerating messages (for example, by focusing on controversial issues and amplifying extreme messages, such as comparing Israeli leaders to Hitler and embedding antisemitic content).

The focus on content relating to internal Israeli issues, such as elections or political protests, suggests a possible intent by the operators of these influence operations to interfere with Israel’s internal discourse and disrupt or influence democratic processes.

In addition to goals related to cognitive efforts and influencing mindsets, some of the operations also involve clear attempts to directly contact Israelis. In the operations studied, these individuals were political activists. Direct contact with Israeli citizens creates a different form of foreign interference, as it involves a hostile foreign agent using Israeli citizens without their knowledge.

Part 4. Lessons from Foreign Interference in Social Networks in Israel

In addition to the value of being the first in-depth study examining foreign interference operations in Israel, we also see its methodological value for conducting similar studies in the future, as well as the tools and technologies necessary for this purpose.

Insights on Foreign Interference Operations in Social Networks

A focus on controversial issues. The operations studied encompass a wide range of issues that are central to the Israeli discourse. It seems that those behind the interference operations have a deep understanding of current events in Israel and adapt their content to address controversial issues. These issues include support for the opposition to current prime ministers, Israeli elections, among others. The content shared also demonstrates familiarity with current events in Israel, such as the cost of living, COVID-19, and so forth.

The investment of resources in the development of influence operations as a sign of state interference. It is clear that significant efforts are made to create accounts that appear authentic by posting substantial content over time. In doing so, these fictitious accounts build credibility. In this way, the fictitious accounts gain credibility, and the communities and channels that they manage attract new followers organically, as people add their friends. This level of investment suggests the involvement of a state entity or entities behind these operations, with significant resources invested in interfering with what is happening in Israel.

Routine activity along with special events. The foreign interference operations on social networks are ongoing, but they also strategically time their actions around key events. As revealed in the interference operations we have studied, the operators identify opportune moments within Israeli public discourse and specific content areas upon which to focus. For example, there are operations that specifically target current events, such as the Knesset elections.

Few responses alongside studying the Israeli public. Despite the significant efforts invested in most of these interference operations, the majority have failed to generate significant publicity or provoke responses from Israeli users. However, it is important to consider two kinds of responses and their implications. First, Israelis have become aware of the presence of hostile influence agents on social media, and they warn about this and respond to them accordingly. Indeed, awareness of the phenomenon has increased over the years, partly due to reports in leading media outlets both in Israel and abroad. The realization that foreign agents are involved in internal discourses could create a sense of insecurity, mistrust, and vulnerability. However, it is possible that this awareness has not gained much attention among the Israeli public because these operations are woven into a domestic discourse of hatred, making it difficult to distinguish the foreign interference (which is disguised as being Israeli) from the authentic internal discourse.

In addition, more sophisticated operations, such as infiltrating WhatsApp groups and creating personal connections through them, have led to situations where Israeli citizens have unknowingly shared information with hostile agents. This poses a risk to Israel’s national security and exploits innocent citizens who are unable to distinguish fake users from real ones and view fake accounts, groups, and channels as credible. The public’s ability to cope with this challenge depends, in part, on the public’s level of digital literacy, and some populations are more vulnerable than others in this sense.

Challenges Inherent in Researching Interference Operations in Social Media

The “glass ceiling” of civil society. It is difficult to prove links with foreign agents without the support of a third party. This study illustrates that without support from third parties—such as assistance from the technological platforms themselves or members of the security establishment—confirming with certainty that accounts are fictitious and that interference operations are conducted by foreign agents is difficult. In most of the cases examined, except for those in which there was direct communication with the operators of the operation, it was not possible to state with absolute certainty that the accounts were part of a foreign influence operation.

“An analogue study in a digital world.” One of the main difficulties of this study was that it relied primarily on analyzing static screenshots of accounts and content. When the study was conducted, much of the content had already been removed from the internet. This limited the ability to add analytical and statistical dimensions to the analysis, perform semantic analyses, and identify patterns in the different operations, in addition to constraining the insights that we could derive from the existing content.

Difficulty Estimating the Impact of the Interference Operations and the Risk Posed to Israel’s Security

A major challenge in studying foreign interference operations on social networks is the difficulty of estimating their impact on Israel’s security, democracy, and national resilience.

This difficulty is similar to measuring marketing efforts aimed at influencing public opinion, as their impact is not necessarily measurable. While operations on many networks have been conducted over a long period without significant achievements, such as accumulating a large following, it is still difficult to accurately estimate their influence on Israel’s national security, even when potential damage exists. For example, during the Balfour protests in 2020, a high-ranking police officer read a call for violence against the police from a social network account during a television broadcast, relying on a fake account posing as one of the protest organizations.[9] Such incidents can deepen rifts and tensions in Israeli society and influence the Israeli discourse. Due to the difficulty of estimating the impact of foreign interference operations on social networks and the intentions behind them, it is also challenging to assess the potential dangers they pose.

Part 5. Addressing Foreign Interference Operations in Social Networks in Israel

Addressing the threat of foreign interference in social networks requires a methodical and systemic approach in cooperation with the variety of entities involved—the security establishment and the tech companies that operate the platforms where the operations are conducted—as well as adapting regulations in Israel to address the problem and involving the public via the media and civil society organizations in the initial identification of suspicious accounts.

Lack of Systemic Treatment of the Threat of Foreign Interference Operations in Social Networks in Israel

The main conclusion drawn from this research is that there is currently a lack of a systematic approach for addressing foreign intervention in social networks in Israel in an organized and methodical manner, from the moment the threat appears until its removal by social media companies. This indicates a need for ongoing, systematic, and continuous research into the phenomenon. Additionally, in our view, a comprehensive perspective is missing—from identifying the operations and assessing the threat they pose, to exposing the networks to the public through the media, and ultimately, removing them from the internet.

Difficulty for Security Agencies in Operating within the Public Civilian Sphere on Social Networks

Foreign interference operations usually take place within the public civilian sphere of social networks, which allows Israelis and foreign entities to interact, posing a significant challenge for the Israeli security forces. The challenge is not only technical, but it also involves concerns about infringing upon the freedom of expression of Israeli citizens, and the fact that sometimes it is not possible to determine with certainty that these are foreign entities. That is, it is possible that those attempting to influence the Israeli discourse by means of coordinated, inauthentic behavior are local. The involvement of civil society bodies could reduce the harm to democratic foundations since civilians report the suspicious profiles and activity, not security agencies. Moreover, intelligence agencies naturally prefer to operate in covert environments, further explaining their limited presence in the public areas of the internet.

The Role of Social Networks in Addressing Foreign Interference

The companies that operate the social networks—primarily Twitter and Meta, which owns Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram—play a decisive role in addressing foreign interference operations. First, the companies have access to information that allows them to identify and monitor foreign interference attempts over time. Moreover, they can remove accounts that are part of these operations. Currently, their technological capabilities in the Hebrew language result in insufficient filtering and identification of content that violates Meta’s community standards.

Existing legislation in Israel is not suitable for addressing foreign interference operations on social networks because it does not provide a means for citizens to directly contact the platforms. There is no clear government point of contact for citizens to report incidents on the networks, no prohibition on the trade of fake user profiles, no legislation mandating the monitoring and removal of fake accounts by the platforms, and insufficient international cooperation with other countries dealing with similar threats on social networks in the legislative, investigative, diplomatic, and intelligence contexts. Another issue is the lack of a direct channel of communication that allows Israeli citizens to contact the tech companies that operate the social networks.[10]

The Dilemma of Media Exposure: Increasing Public Awareness or Strengthening Hostile Agents?

One of the main approaches globally in dealing with disinformation and post-truth is educating the public on digital literacy.[11] From this perspective, exposing foreign interference operations on social networks in Israel helps raise the public’s awareness and increase skepticism toward fake accounts or those suspected of being fake. In other words, media exposure has value in improving the general public’s digital literacy, and the public can be enlisted in actively taking part in identifying suspicious accounts.

However, it is also important to understand the cost of exposure and its long-term consequences. First, exposing the networks can embolden their operators, incentivizing them to continue their interference operations by demonstrating their impact on the Israeli public, gaining publicity, and influencing the national agenda. In addition, once the operations are exposed, they can be used as a tool for political mudslinging, thus serving the goals of the operators and deepening the divisions and rifts within Israeli society.

Part 6. Recommendations for Action, Policy, and Legislation

Systemic Recommendations:

One of the main conclusions is that currently no single body in Israel conducts systematic and consistent research regarding the threat of foreign interference on social networks in Israel. As a result, the issue falls between the cracks and relies on the efforts of the security establishment and civil society, which address it in an uncoordinated manner. Although the issue falls under the responsibility of the Israel Security Services (Shin Bet), there are reasons why it does not receive optimal attention. Our recommendation is to establish a dedicated body for in-depth and ongoing research on interference operations. This body should focus not only on real-time removal but also on identifying patterns of activity, characteristics, and so forth. This body will require intelligence, technological, and analytical capabilities. Working in synchronization and coordination with all relevant actors, this body should consider all the implications, including the decision of when to expose foreign influence networks to the public. Establishing this body will help regulate the relationship between intelligence agencies and civil society organizations.

A systematic and continuous study of the issue will provide deeper insights into the adversary’s patterns of action. It will also allow for better and faster identification of interference operations on social networks and prompt response to intervention operations in emergencies and routine situations. Ongoing study of the issue will help monitor the learning and development of interference operations and equip the public with tools to deal with them. We recommend strengthening the research on foreign influence and intervention in social networks within the security system as well as among civilian entities such as research institutes and NGOs.

Meanwhile, the intelligence community, led by the Shin Bet, should expand its involvement in addressing the threat of foreign interference in social networks in Israel. This expansion should involve continuous activity, beyond just elections, and additional bodies besides the Shin Bet should be included.

While this study focused on interference operations on social networks where content was posted only in Hebrew, it is imperative to continue researching operations that target Israeli citizens who speak other languages, such as Arabic, Russian, Amharic, and so forth.

Furthermore, it is important to expand research to additional platforms where interference operations are used, such as TikTok and LinkedIn, which were not examined in this study. Over time, monitoring should be expanded to any new social networks that develop. Additionally, it is essential to monitor new technologies employed by interference operators, such as generative AI technologies.

Recommendations Relating to Government Ministries

With respect to government bodies, there should be increased awareness of the threat of foreign interference and influence in democratic processes in general, and in social networks in particular, as a significant new threat to national security and resilience. To this end, awareness should be raised among individuals in relevant government ministries (the Ministry of Justice), law enforcement (the Israel Police), and the relevant authorities (the Central Elections Committee, National Cyber Directorate, NSC, National Digital Agency), which should be designated as responsible for addressing the problem. Moreover, the public should have an accessible means to report possible foreign interference on social networks. Increasing the awareness of government bodies can lead to the advancement of necessary regulation on social networks.

Recommendations Relating to Regulation in Israel

There is a need for legislation that would require the major social networks to create a direct communication channel for Israeli residents to report complaints and receive clarifications related to content. In addition, legislation should prohibit the trade in fake users and empower state authorities to take action against the operators of fake accounts. It should also obligate the platforms to monitor and remove these accounts and to cooperate with other countries in addressing the risks of foreign interference in social networks within the legislative, investigative, diplomatic, and intelligence contexts. In this framework, it is necessary to supervise and restrict the architecture of the platforms, including their algorithmic engine and business models, while maintaining the end users’ freedom of expression. Finally, there is a need to update privacy legislation in Israel.

First, tech companies should invest in allocating resources and technologies that are adapted to the languages spoken in Israel, primarily Hebrew and Arabic. Relevant recommendations can also be found in Facebook’s report following Operation Guardian of the Walls. Social networks should allocate local monitoring teams and deploy fact-checkers familiar with Israel’s languages and cultures. It is important to ensure that the service is responsive to Israeli queries, aligned with local time zones, and that inquiries by civilian and state bodies are answered in a sufficient time period before events on the social networks get out of control.

The Committee to Adapt the Law to the Challenges of Innovation and the Acceleration of Technology (the Davidi Committee), which operated on behalf of the Ministry of Justice in the 36th government, called for the establishment of a regulatory body for digital activity.[12] Currently, the state’s contact with the platforms is managed by the Ministry of Justice’s Cyber Unit. In 2020, over 4,000 requests to remove information from social networks were submitted to the Cyber Unit by security agencies, constituting 94% of all the requests made. In the case of Adalah v. the State Attorney—Cyber Unit, the High Court of Justice (HCJ) determined that “the activity of the Cyber Unit in its current format is essential to the immediate preservation of national security and social order, but it is not free of difficulties, which relate mainly to the problem of authorization in primary private legislation for the unit’s activities.” The Ministry of Justice is not authorized in legislation to take action against the social networks; thus, the HCJ recommended arranging such authorization in legislation.

At the same time, in the 36th government, a committee in the Ministry of Communications examined regulating digital content platforms.[13] One of the committee’s proposals, which was adopted in December 2022 by the former minister of communications,[14] was the establishment of a public council with the purpose of increasing the supervision of social networks. According to the proposal, the council would be chosen by government and civil society leaders and would serve as a contact point for public complaints about foreign interference as well as to help formulate policy.[15]

In general, we recommend removing any coordinated inauthentic activity suspected to be foreign, regardless of its impact, the messages published, or actions taken following its activity. It is essential to reach an understanding with tech companies to share information about foreign interference operations they identify on social networks targeting Israel and to deepen research and understanding of adversary activities with maximum transparency.

Recommendations Relating to Civil Society

This research highlights the critical role of research institutes and civil society organizations in addressing the phenomenon of foreign interference in social networks in Israel. These entities are able to identify and monitor potential cases of foreign interference, raise public awareness about this phenomenon, and advance targeted research on this issue. However, this study also illustrates the limitations of civil society in dealing with the issue and the need to cooperate with state bodies and tech companies that operate the platforms to effectively address and mitigate the issue.

Recommendations Relating to the Israeli Public

Enhancing the public’s digital literacy is crucial so that Israeli citizens can learn to identify fake accounts that operate in their digital environment and attempt to mislead them as part of interference operations. Responsibility should be given to a body that addresses this issue regularly, and not just around events such as Knesset elections or wars. One possibility is to incorporate the subject into the curriculum of the Ministry of Education and to appoint the National Digital Unit to be responsible for promoting digital literacy among the adult population.

Additionally, partnerships should be initiated with relevant bodies around current events that could serve as fertile ground for foreign interference operations, such as the Home Front Command during military operations, the Central Elections Committee during election campaigns, and so forth. The main issue is to appoint a dedicated body responsible for this issue in routine times, which will receive budgets for public awareness and education efforts. The public council mentioned above, which includes public representatives, could be the basis for such a body. Other relevant entities include the National Cyber Directorate, the Ministry of Intelligence, civil society organizations, and research institutes that can characterize the phenomenon and develop ways to address it. When a communication channel is established between the public and the tech companies that operate the social networks, and a clear national point of contact is created to which the public can report security incidents on social networks, it will be important to inform the public of their existence and encourage their use. This way, the public can also complain about interactions with foreign agents.

Recommendations Relating to the Traditional Media

The traditional mass media—television channels, news sites, radio, and newspapers—play a role in increasing the public’s awareness of foreign interference operations in social networks. Thus, it is important for the media to expose some of the operations to improve the public’s digital literacy. However, there is a risk that media exposure may encourage the agents behind such interference operations to continue their activities within the social networks in Israel. After considering the various perspectives, we have concluded that, as a rule, it is worthwhile to publicize these interference attempts. The consideration of raising public awareness (as part of a means of protection and creating resilience) outweighs the concern of giving resonance to foreign subversive activities. However, in cases where national security is at risk, or there is a potential to enhance the research and achieve significant insights by monitoring the operation, delaying public disclosure should be considered. To facilitate this, the establishment of a military-civilian advisory forum is recommended. Furthermore, it is also important to raise awareness among journalists who specialize in covering state and security issues across different media platforms regarding the existence of interference operations on social networks, including the spread of disinformation. This would enable them to deepen their understanding of the impact of these operations on Israeli democracy, given how the incidents can spill over from the internet to traditional media.

Recommendations for Future Studies

To understand the current state of foreign interference operations and the latest approaches used, ongoing, systematic research is needed. This research should focus on identifying patterns of the adversary to see how operations change and develop over time. It is important to investigate the causes of these changes, whether they result from measures taken by Israel or steps taken by the social networks themselves, and so forth. Technological developments, for example, such as the accessibility of generative artificial intelligence technologies can affect these operations in ways that challenge some of the insights presented in this study (for example, identifying foreign interference operations based on elements related to language, reducing the need to steal photos because it is possible to create photos for fictitious accounts that look credible, and more). In 2022, over two-thirds of the coordinated, inauthentic operations on Meta used accounts with photos generated by GAN technology. The operators may think that by using these pictures, their accounts appear more authentic and genuine and can deceive bodies that investigate interference operations and rely on overt information. This presents a significant challenge in identifying and investigating interference operations. Changes in interference operations can also be influenced by the emergence of new social platforms, such as Telegram or TikTok, and increased usage of them. The way that fake accounts operate in interference operations has also changed, and a transition to smaller, more focused operations is evident, where fewer accounts are involved compared to larger and more disruptive operations seen in the past. This type of systematic and consistent research of interference operations should rely on a range of information sources, including a mechanized framework for information gathering and analysis, as well as information collected and published by research bodies and civil society organizations both in Israel and abroad. Effective identification, warning, and research efforts require a combination of skilled analysts, technological tools capable of handling and preserving large amounts of information, as well as issuing urgent warnings about significant incidents on the internet.

Among the challenges in the field, attributing the accounts to the organizations and individuals behind them, as well as providing concrete proof of their involvement and incriminating them are particularly difficult. This difficulty is rooted in user privacy protection provided by the social networks, which includes masking identification data and other user details. Consequently, it is impossible to discover IP addresses, email addresses, geographical locations, and phone numbers of accounts in general, and especially those involved in inauthentic activity. In contrast, automated tools for alerting, connecting, and monitoring interference operations could be highly effective.

We recommend emphasizing the technological context in the following fields:

- Invest in a reliable database that is updated over time—a fundamental component of any “defensive enterprise” needs to have the ability to “harvest” and “store” information from the relevant networks over time. To effectively combat interference threats over a wide variety of platforms (TikTok, WhatsApp, Telegram, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, and more), it is necessary to implement various methods of retrieving the information and gathering it over time for the purpose of applying statistical analysis and performing retroactive identification of malicious accounts.

- Invest in metadata tools for identifying suspicious, coordinated online activity.

- Invest in semantic processing and content-based processing tools to automatically detect “inflammatory” messages, to identify posts that have common language errors indicating they were written by non-Hebrew speakers (requires research), and to detect content created by deepfake algorithms as part of addressing the growing challenge in the field of generative AI.

[1] Central Bureau of Statistics, “Well Being, Sustainability, and National Resilience Indicators, 2021,” Part 11, “Internet and Technology,” https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/doclib/2022/1873_well_being_2021/prt11_5_h.pdf

[2] Facebook, “Threat Report: The State of Influence Operations 2017–2020,” May 2021, https://about.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/IO-Threat-Report-May-20-2021.pdf

[3] Meta, “October 2020 Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Report,” November 5, 2020, https://about.fb.com/news/2020/11/october-2020-cib-report/

[4] Graphika, “Capture the Flag: Iranian Operators Impersonate Anti-Netanyahu ‘Black Flag’ Protestors, Amplify Iranian Narratives,” November 2020, https://public-assets.graphika.com/reports/graphika_report_capture_the_flag.pdf

[5] Oren Aharoni, “Investigation: Who Is Trying to Impersonate Black Flag Activists?,” KAN, March 3, 2021, https://www.kan.org.il/content/kan-news/politic/281335/

[6] FakeReporter, “Under the guise of a Haredi network organization, an Iranian cell has been operating on social media for months..” [in Hebrew] X (formerly Twitter), February 3, 2022, https://twitter.com/fakereporter/status/1489164051011846144

[7] Tom Bateman, “Iran Accused of Sowing Israel Discontent with Fake Jewish Facebook Group,” BBC, February 3, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-60229146

[8] Dafna Liel, “Report: This Is How an Iranian Network Disseminates Content in Israel—In Order to Inflame the Political Debate,” [in Hebrew] N12, December 29, 2021, https://www.mako.co.il/news-digital/2021_q4/Article-5496b9571470e71026.htm

[9] Lior Kenan and Amit Maniv, “The Police: The Claim that Demonstrators Called for Violence Was Based on Fake News,” [in Hebrew] Channel 13, https://13tv.co.il/item/news/politics/security/fake-news-police-crime-minister-1139597/

[10] Digital Sovereignty: How the New Government Should Address the Dissemination of Fake News and Influence Operations [in Hebrew], INSS, https://www.inss.org.il/he/publication/truth1/

[11] For an example of addressing misinformation in Finland via educating the public on digital literacy, see Jenny Gross, “How Finland Is Teaching a Generation to Spot Misinformation,” New York Times, January 10, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/10/world/europe/finland-misinformation-classes.html

[12] Ministry of Justice, “Summary of the Committee’s Work on Adapting the Law to the Challenges of Innovation and Accelerating Technology, Regarding Illegal Content in the Digital Space,” [in Hebrew] October 2022,

https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/guide/davidi-committee-main/he/committee-summary.pdf

[13] The Advisory Committee to the Minister of Communications on Examining the Regulation of Digital Content Platforms, “Recommendations of the Committee,” [in Hebrew] December 2022, https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/14122022/he/Report-digital-platforms.pdf

[14] Ministry of Communications, “Report of the Advisory Committee to the Minister of Communications on Examining the Regulation of Digital Content Platforms,” [in Hebrew] December 14, 2022, https://www.gov.il/he/pages/14122022

[15] Tamir Hayman, David Siman-Tov, and Amos Hervitz, “Regulation of Social Media in Israel,” INSS Insight No. 1679, January 8, 2023, https://www.inss.org.il/publication/social-media/