Publications

A special joint publication by the Institute for National Security Studies and the Institute for the Research of the Methodology of Intelligence at the Israel Intelligence Heritage and Commemoration Center, February 2025

This article discusses influence operations aimed at harming Israeli economic and security interests in the international arena, with a focus on two case studies in the United Kingdom and Japan. In both cases, Elbit Systems was targeted for economic and strategic influence and damage. The article describes the operational methods used in the influence operations on social networks, which include coordinating between activist organizations and coordinated inauthentic behavior networks on social media. In addition, it proposes initial directions for addressing these threats, including strengthening the ability to identify coordinated influence operations in social networks, developing international and civilian-security collaborations, strengthening digital resilience, and formulating legal and security action mechanisms for addressing influence operations in the digital arena.[2]

Intentional manipulation on social networks is a tool used by many states and organizations to influence the digital realm of their adversaries, shaping public opinion, public behavior, and specific target audiences within the adversary’s system. In particular, Russia’s and China’s activities against the United States and the West in this field have gained publicity. When such activities are deliberately designed to negatively influence political processes and public opinion in ways that contradict the values and norms of the targeted side, they may be considered acts of “foreign interference.” Unlike influence operations in the Israeli digital realm (by Iran, for example), this article describes a different type of operation designed to harm Israeli interests in other countries by influencing their digital realm.

Coordinated inauthentic behavior (CIB) networks on social media (see the definitions section) are large groups of accounts built and maintained by political organizations, governments, and entities that provide this service for a fee. The operation of these networks requires unique knowledge such as identity creation techniques, coordinated promotion of content, and a mechanism for the simultaneous command and control of thousands of automated accounts (bots) or human accounts. These networks are a central means for organizations, countries, and other strategic actors to attain fast and broad exposure to diverse target audiences and to produce change in public opinion or in the behavior of selected targeted audiences. They also allow messages to seep into the traditional media in these arenas.

Since October 7, 2023, attempts have been made by many entities in the international arena to leverage the public atmosphere to harm the economic, security, and national interests of the State of Israel around the world in a targeted manner. In this article, we will present an analysis of two case studies—one in the United Kingdom and the other in Japan—highlighting the familiar operational patterns of BDS organizations alongside a new pattern of support for these hostile operations by entities operating large groups of accounts on social media. These CIB networks, some with false and inauthentic identities, use advanced influence techniques to help the hostile activist organizations achieve broad public exposure and mobilize select target audiences to take action. Our assessment is that behind these CIB networks are Islamist organizations, political entities, and possibly also states, rather than these activist organizations directly operating the influence operations described. The scale of these networks (thousands of accounts) and other data, such as the variety of issues they address over time and the language of the activity in the Japanese case, show that this is not a one-off effort but rather the involvement of an entity or organization that is primarily engaged in this over time.

These two cases represent, as far as we know, the first cases after October 7 that clearly combine the efforts of both activist groups operating physically in the international arena against Israel with extensive coordinated activity on social media. This dual approach warrants analysis and offers valuable lessons. These two cases also illustrate how influence activity on social media can help cause real, targeted damage to Israeli interests, not merely through indirect participation in the general public discourse on social media and by influencing global public opinion, but especially in the hostile climate that has emerged since October 7.

In this article, we discuss influence operations directed toward the public and civilian sectors of target countries that are characterized by the extensive use of tools such as social media platforms, CIB networks, traditional media and journalism, and activity on the ground. The key characteristics of influence operations include having a clearly defined goal, sometimes with a specific date for achieving the desired result; a well-conceived plan that integrates several different information distribution capabilities; and centralized management of planning and execution.

The primary aim of this article is to highlight the threat posed to Israel’s economic, security, and national interests by the operators of CIB networks on social media. These operations have joined forces with entities hostile to Israel in international arenas to influence local audiences. In addition, this article seeks to demonstrate the central role of CIB networks as a tool in influence operations and the damage that they can inflict in the Israeli digital realm.

In the concluding section, we will outline initial directions for addressing the threat of influence operations against Israeli interests in the international arena. One challenge lies in the absence of a central body within the State of Israel tasked with coordinating and leading responses to influence threats on social media. Furthermore, addressing influence operations impacting Israeli interests within friendly countries presents unique complexities. To meet these challenges, we offer recommendations to adapt Israel’s national toolkit, focusing on legal channels, enhanced collaboration between Israeli and foreign authorities, and more tailored involvement by security and intelligence agencies.

This article was developed in collaboration with the technological platform of the company Next Dim, which specializes in analyzing and identifying anomalous patterns within large information networks, particularly in social media and financial networks. This special publication is part of a broader collaboration between the company and INSS, alongside its partnerships with academia and investigative journalism, aimed at bolstering defense against and raising awareness of influence operations.

Conceptual Framework

In this section, we will present the key concepts that we have used in analyzing the case studies. First, we provide two basic concepts that define “foreign interference” as the behavior exhibited by strategic actors in the international arena, and then we define the means of implementation and the tools employed in the specific tactical influence operations discussed.

Foreign interference is defined by Ofer Fridman as an international actor’s use of a combination of instruments of power to achieve political objectives vis-à-vis another actor in a manner that contradicts the values, norms, and laws of the targeted entity.[4] According to this definition, it is more difficult to determine if the influence operations discussed in this article are “foreign interference” operations because it is not always possible to determine to what extent their tools and norms conflict with the values of the specific international arenas where they operate. However, the coordinated use of networks of inauthentic accounts on social media is considered unethical and contrary to both the policy of the operators of the social media platforms themselves and to behavioral norms in some countries.

Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) is described by the European External Action Service as “a mostly non-illegal pattern of behaviour that threatens or has the potential to negatively impact values, procedures and political processes. Such activity is manipulative in character, conducted in an intentional and coordinated manner. Actors of such activity can be state or non-state actors, including their proxies inside and outside of their own territory.”[5] This definition fits the pattern of activity of the influence operations that we discuss in this article.

A similar term used by the Foreign Malign Influence Center at the US Department of Intelligence is Foreign Malign Influence,[6] which falls under “gray zone activities,” similar to hybrid warfare.[7] This definition underscores the relatively broad gray zone often involved in responding to foreign influence, a characteristic of the cases presented here. Sometimes, even when it comes to a coordinated and manipulative influence operation, it does not present false information or clearly break the law in the arena of activity. Intelligence organizations and states recognize this complexity and the need to address it in order to protect democratic values and public order vis-à-vis external and internal hostile entities.

An influence operation is defined by the RAND Corporation as a planned, coordinated, and synchronized effort using various means, such as information, media, social media platforms, and economic, diplomatic, legal, and military tools to influence the decision-making or behavior of a target audience.[8] This definition is very broad and includes a wide range of actions for diverse purposes using an array of tools. For example, a strategic economic investment in a foreign country’s infrastructure could be considered an influence operation under this definition.

Coordinated inauthentic behavior (CIB) was first defined by Meta as a group of users, including fake accounts, whose activities and interconnections demonstrate coordinated and synchronized efforts to promote and disseminate a message to the widest possible audience.[9] The term is commonly used to describe the operational methods employed by organizations and states on social media platforms.[10] We also apply this term more broadly to encompass additional platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, and others, to denote a pattern of activity where political organizations, governments, and entities offering paid services establish and operate extensive groups of accounts over time to exert influence in the digital space. Operating these networks requires specialized knowledge, such as techniques for identity creation, coordinated content promotion, and systems for simultaneous command and control of thousands of accounts—whether automated (bots), human, or hybrid.

Case 1: The #ShutElbitDown Campaign in the UK

Elbit Systems Ltd. is an Israeli military technology company that develops and produces combat systems in fields such as electronics, electro-optics, artillery, aviation, lasers, and more. The company operates globally and is publicly traded on the Nasdaq Stock Exchange in the United States and the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. Elbit has subsidiaries in the US, the UK, the EU, and Brazil.

In the operation discussed here, a small group of organizations collaborated with a coordinated network of numerous accounts on X (previously known as Twitter), primarily driven by the organization Palestine Action UK.[11] The coordinated social media activity significantly expanded the exposure of these organizations and their activities, achieving an unprecedented reach of 30 million views of the relevant posts on X. The number of proactive user engagements on this issue by X users surged from an average of about 12,000 interactions in the month before October 7, 2023, to an average of 112,000 interactions in the following month.

This increase in coordinated activity amplified the exposure of Palestine Action UK’s initiatives and received media coverage as well as responses from politicians. For example, Jeremy Corbyn, a former member of the British Parliament, publicly supported the organization’s actions in a post on X on December 21, 2023 (see Figure 1), which received 152,000 views.

Figure 1 Jeremy Corbyn’s Tweet

The Organizations Identified as Participating in the Operation

Palestine Action UK. Palestine Action UK is a small group of activists in the UK that emerged from the BDS movement between 2017 and 2020.[12] The group’s primary focus is targeting Elbit Systems as part of its pro-Palestinian and anti-Israel agenda. The organization has a website and social media channels, and it carries out actions such as blocking factory entrances, spray painting graffiti, and engaging in vandalism, which are documented and disseminated on social media.[13]

Figure 2 Two of the Organization’s Activists Blocking an Elbit Factory in the UK in October 2021

Since 2020, Palestine Action UK’s stated objective has been to shut down Elbit’s factories in the UK through direct pressure tactics, including physical protests aimed at various stakeholders such as legislators, companies, and the owners of the properties where the factories are located. The organization has also established secondary cells in the US, Germany, and Australia, most of which became active after October 7, 2023. These cells maintain certain ties with the BDS movement and were partly formed through joint operations with a CIB network described below.

A Coordinated Network of Accounts on X. This network consists of English-language accounts that, based on content analysis, appear to be operated by individuals in the UK with an Islamist activist orientation. This network played a central role in increasing the exposure of Palestine Action UK’s activities on social media platforms. The network’s methods of operation, discussed later in this section, focus on engaging and maintaining interactions with a local British target audience, particularly members of the Muslim community in the UK.

Progressive International. This organization joined the activity at a later stage to help internationalize Palestine Action UK’s campaign against Elbit. Progressive International describes itself as an umbrella organization that aims to unify and coordinate the efforts of dozens of groups worldwide with a progressive agenda, promoting a “post-capitalist” society and opposing imperialism. The organization has received endorsements from progressive left politicians and public figures, including Noam Chomsky, Bernie Sanders, and Jeremy Corbyn.[14]

Course of the Operation

In October 2023, Palestine Action UK expanded its activities, which included demonstrations, spray-painting Elbit facilities with red paint, attempted break-ins, and acts of vandalism. A key development was the increased visibility on social media platforms, driven not only by the organization’s own accounts and supporters but also by a coordinated network of thousands of accounts designed to amplify their demonstrations and content on X and other platforms not included in this paper. According to Next Dim’s systems, this network displayed clear characteristics of CIB, as discussed below. The online activity was marked by the use of the hashtag #ShutElbitDown, a signature associated with the organization.

During the joint operation with the CIB network, the number of followers of the organization’s Twitter account grew from about 60,000 to 128,000 within about two months of intensive activity. This contrasts with the account’s annual average growth of about 20,000 followers since 2021. A subsequent review revealed that many of these new followers were created after October 7 and exhibited low levels of activity, suggesting that an artificial effort was made to promote the account’s exposure by increasing the number of followers.

The main achievements at this stage were expanding the organization’s activities in the UK and increasing its online presence and the number of followers. In the next phase of the operation, Palestine Action UK collaborated with Progressive International, and on December 21, 2023 (see Figure 3), they held a coordinated day called “Global Day of Action Against Elbit Systems,” involving demonstrations at Elbit sites worldwide, including the UK, Brazil, the US, and other locations.[15] This event marked a clear expansion, with additional activist organizations joining the efforts for the first time. Various organizations produced placards and materials that were promoted on social media platforms and organized demonstrations as well as acts of vandalism, all of which received significant exposure.

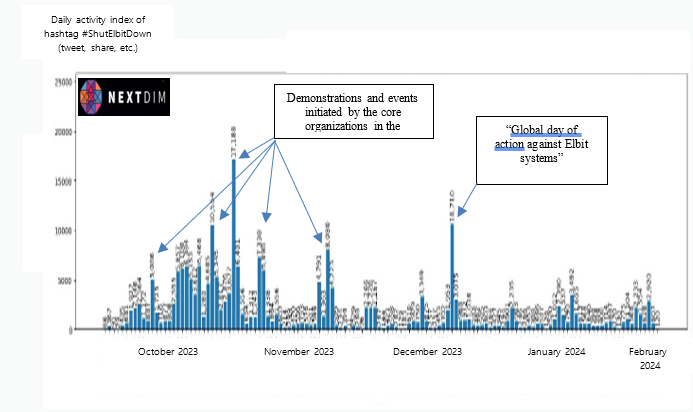

Figure 3 Daily Proactive Activity by Users Promoting #ShutElbitDown Content (October 1, 2023, to February 7, 2024)

Figure 3 shows a timeline of internet activity, represented by the blue columns that measure the daily usage of the hashtag #ShutElbitDown as a measure of the activity of the CIB network in this operation. The first significant and simultaneous surge in the organization’s activity was observed on October 12, 2023, around the days when Palestine Action organized physical actions at Elbit’s factories. Subsequently, there was a noticeable increase in activity, concentrated on the days of coordinated efforts, with the CIB network focusing solely on this issue during these periods. This kind of behavior is characteristic of CIB networks that promote a certain issue in a timed, simultaneous manner. The total amount of activity under the hashtag #ShutElbitDown reached an all-time peak during these months. Although this hashtag was first used by British BDS activists on X as early as 2018, it only gained more extensive exposure after October 7, due to the CIB network’s targeted promotion.

The CIB network that operated as part of this influence operation comprised coordinated accounts promoting pro-Palestinian agendas, often associated with Hamas or other Islamic groups, and primarily targeted Muslim populations in the UK, as well as potentially other segments of the British population. While the CIB network has been operating for some time, it began focusing on the campaign against Elbit during the events described in this section. Although the operators behind the network are unknown, activity patterns suggest that some coordination began with Palestine Action UK in October 2023.

Next Dim’s algorithms identified approximately 1,500 Twitter users suspected of belonging to this CIB network, geographically marked as British. These accounts exhibited various abnormal CIB metrics and internet relations, including a relatively high number of mutual follower-following relations.

Other CIB characteristics are:

- Performing unusually large numbers of actions within short time periods.

- Utilizing coordination techniques such as “Twitter bombing,” where identical content is posted simultaneously by a large number of accounts, and responding to posts with lists of hashtags and synchronized content and timing.

- A significant number of users with “purpose-built” accounts, characterized by vague human identities, sometimes no followers, limited activity on specific issues, and creation dates aligning with targeted campaigns.

- The presence of relatively new users who engage in the issue (in the #ShutElbitDown hashtag issue, there were around 2,350 new users), suggesting the creation of accounts as part of coordinated and directed activity.

It appears that the CIB network began working in a synchronized manner with the #ShutElbitDown campaign on October 12, coinciding with the first demonstration organized by Palestine Action. From that point onward, the network intensively promoted the content of the accounts involved in the campaign.

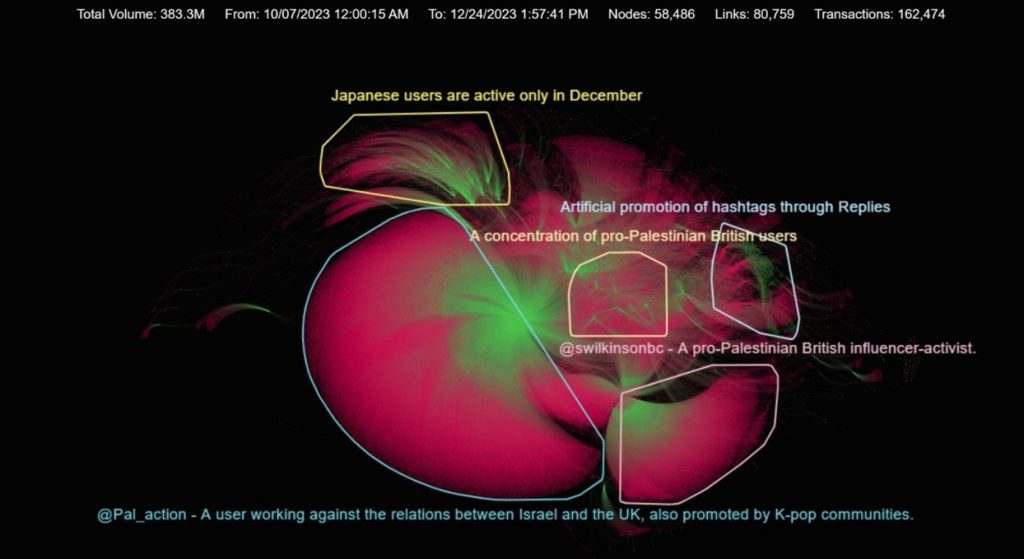

Figure 4 presents users who used the hashtag #ShutElbitDown between October and January. Two main sources of activity are visible (in green): the larger of the two being Palestine Action’s account, followed by the activist Sara Wilkinson, who has tens of thousands of followers. The majority of the remaining activity shown in the graph is characterized by abnormally coordinated behavior around a group of accounts labeled as a “concentration of liberal Brits.” Another coordinated group of users, labeled “Japanese accounts,” is also visible; these are part of the broader CIB network described in the next section.

Figure 4 Users Active Between October and January Who Used the Hashtag #ShutElbitDown

Figure 5 illustrates the method of operation employed by coordinated users through a technique called “Twitter bombing.” This involves different users disseminating posts with identical content either within a short period of time or simultaneously. The users on the left and in the middle are influencers with a medium to large number of followers, and the user on the right is suspected of being a purpose-built account, exhibiting the following key characteristics: created in October 2023, an identical number of followers and following (149), and solely engaged in the coordinated amplification of pro-Palestinian issues. These features are indicative of a CIB campaign.

Figure 5 Visual Illustration of Coordinated Activity and Connections Between Influencers and Purpose-built Users

Results of the Operation

In press interviews conducted by Palestine Action UK at the end of December 2023, amid their prosecution in the UK for property damage, the organization’s founders shared their worldview, offering insight into the objectives of the influence operation.[16] They expressed their disappointment with the legal and divestment channels, as well as a strong conviction that only global “direct action” involving physical damage to Elbit factories throughout the world would effectively harm the company in the long term. This perspective, expressed two weeks after the events described in this chapter, helps explain the motives and methods used by active organizations and highlights the role of the CIB network. Our assessment is that these activities were intended to target UK audiences with an Islamic orientation, aiming to expand their network of volunteers for direct action, establish international chapters, and mobilize organizations and individuals for acts of vandalism on a global scale.

During the operation, which lasted about two and a half months, anti-Elbit activity increased by several orders of magnitude (thousands of percent) in terms of online exposure and media coverage. What had initially been largely a UK-focused effort escalated into a wave of simultaneous violent protests in countries such as the United States, Brazil, Japan, and Australia, peaking in December 2023. Although there was no significant functional damage to Elbit’s factories in the United Kingdom or worldwide, the presumed objectives were largely achieved. Palestine Action UK expanded its network of collaborations and gained support and recognition from various political and progressive figures. Our assessment indicates that their intensive online activity broadened the organization’s followers as well as its pool of volunteers through its recruitment efforts on social media and the organization’s website.

Case 2: The Influence Operation to Sever Relations Between Elbit and the Japanese Company Itochu

In this influence operation, Japanese BDS groups, political bodies, and a CIB network operated by a confidential entity collaborated in a coordinated manner. The entity behind the CIB network may be linked to Japanese political bodies, business interests, or foreign governments with vested interests. The operation aimed to cancel the collaboration agreement between the Japanese company Itochu and Elbit, signed in March 2023, by capitalizing on the polarization surrounding the war in Gaza.

Itochu is one of Japan’s largest trading companies, with about $104 billion in sales in 2023.[17] Under a memorandum of understanding signed in March 2023 between Elbit, Nippon Aircraft Supply, and Itochu Aviation, Elbit agreed to provide Japan with technological knowledge and core components of its military systems. These components would be produced in Japan to meet the specific needs of the Japanese military. Itochu’s role was to work with Japan’s Ministry of Defense and the military while providing logistical assistance, similar to its work with other major defense manufacturers such as Boeing, Raytheon, and Lockheed Martin.[18] Thanks to this agreement, Elbit gained exposure to a market with enormous potential, particularly given Japan’s urgent need for rearmament in response to heightened tensions in the China Sea.[19]

The Organizations Identified as Participating in the Operation

A large variety of organizations and entities participated in the activities described below:

A CIB Network of Japanese Users on X. This network comprises a large group of accounts exhibiting salient features of inauthentic and coordinated behavior. It includes at least 2,600 users with abnormal mutual connections, about 800 users without followers, and hundreds of accounts that were opened around the time of the campaign and only promote its content. Another unusual quantitative metric characterizing the network’s coordinated activity is the average number of actions per user, which is significantly higher compared to other users in the campaign who used the relevant hashtag. The users identify as Japanese and have previously supported, in a coordinated manner, various political campaigns in Japan. These include a campaign against the decision of Prime Minister Suga to hold the Olympics in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic, a campaign against the government and the Dentsu corporation over alleged irregularities in the distribution of COVID-19 grants, and protests against the establishment of an American base in Okinawa during a referendum on the issue in 2019. This network began engaging intensively and simultaneously on the issue of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and Elbit in December 2023. Such behavior is characteristic of CIB networks and unlikely to be the result of organic user activity.

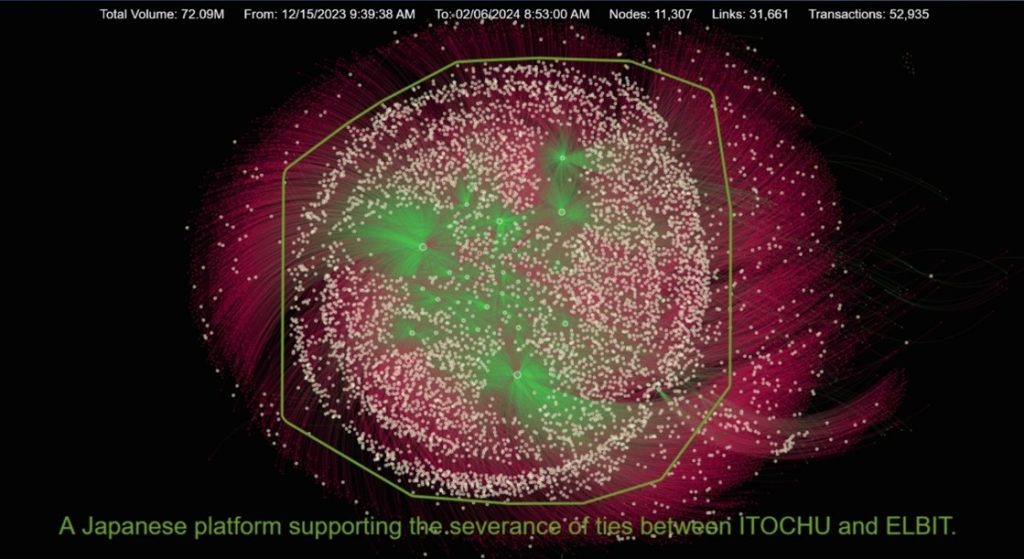

Figure 6 shows a visualization of the CIB network. The content sources (posts) are shown in green and include the accounts of partner organizations involved in the operation. Accounts interacting with the content through replies or retweets appear in red, while accounts identified as part of the Japanese CIB network, which exhibit abnormal coordination characteristics, are displayed in white. The significant concentration of coordinated accounts is evident among all observed activity surrounding the #ShutElbitDown hashtag, reflecting a deliberate and concerted effort by the CIB network.

Figure 6 Internet Graph of the Network of Users Participating in the Online Campaign on December 15, 2023, and February 7, 2024

A Field Operations Cell. A group that adopted the name “Students and Youths for Palestine” was organized specifically for this operation. This group organized and carried out most of the actions on the ground, including demonstrations and petition writing. It had two volunteer groups: one identified as a group of Japanese student activists called “Omou Palestine” (@Omou_palestine, 2,949 followers on Twitter) and the other as local Palestinian volunteers in Japan named “Palestinians of Japan” (POF).

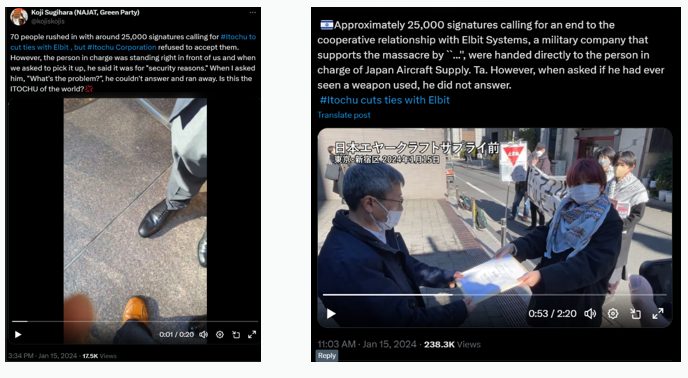

Political Organizations. Two key organizations were identified as integral parts of the operation. The first one appears to be a Japanese chapter of the BDS movement and may be responsible for establishing links with a previous campaign in the UK. The other organization, Networks Against Japan Arms Trade (NAJAT),[20] is a Japanese non-governmental organization affiliated with the Green Party that actively opposes Japan’s export of weapon systems. Koji Sugihara, a representative of the organization with about 14,000 followers on X,[21] participated in public protest events and also submitted a petition to Itochu’s representatives in a high-profile, in-person act.

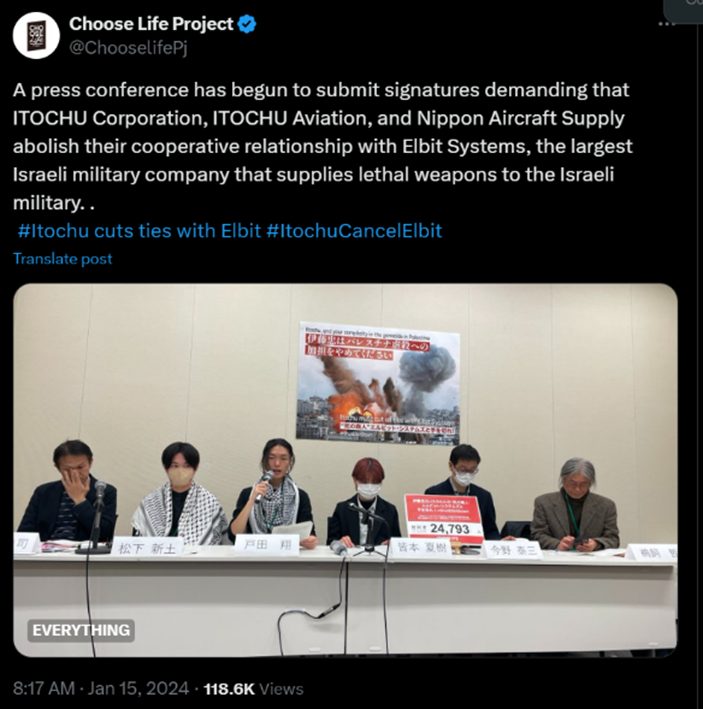

A Media Channel That Identifies as Independent. Choose Life, a digital news channel that identifies as independent, played a major role in the campaign. Established in 2016, the channel underwent various transformations before it became a digital news platform. It operates a website and social media accounts,[22] producing videos, graphics, and content aligned with the Japanese left. With a following of 65,000 on X (@ChooselifePj), the channel was instrumental in creating content and graphics for demonstrations, directing most of its activity toward severing Elbit’s relations in Japan. Whether the channel is influenced by other parties beyond its management is unclear.

The Course of the Operation

The central strategy of the campaign appeared to leverage the sensitive topic of the war in Gaza to apply public and personal pressure on the management of the two companies, Itochu and NAS (Nippon Aircraft Supply), with the aim of causing them to sever their cooperation agreement with Elbit.

The campaign’s activities were structured around a petition, which the participating organizations openly initiated and presented during a press conference. Japan has long had heightened public sensitivity regarding arms exports. The petition highlighted the arms exports and the “forbidden” partnership with Elbit, accusing the company of participating in genocide. Using these two false allegations, the campaign established a narrative to remind the management of the Japanese companies that arms exports are a particularly delicate issue in Japan and are restricted to situations promoting peace and stability.

Following the petition’s release, a series of demonstrations took place, with various bodies simultaneously acting both in person and online through the CIB network to produce maximum exposure. Demonstrators then physically delivered the petition to the company executives at the entrance to the companies’ offices.

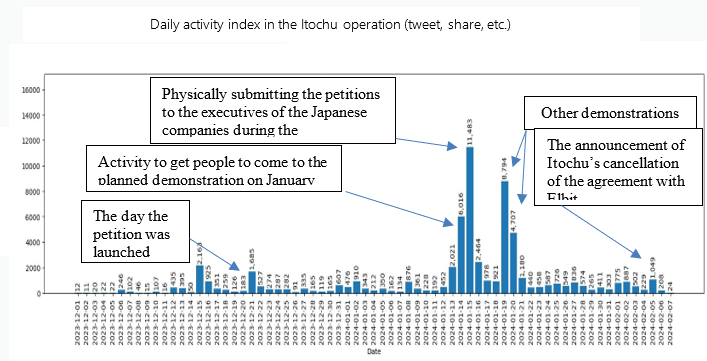

The organizational infrastructure for these demonstrations appears to have relied on a core group that included BDS Japan and a collection of volunteers who had only begun operating as a group at the end of October, having rarely addressed the Palestinian issue before then. After about three months of diverse pro-Palestinian activity, all groups involved rapidly shifted their focus to the campaign against Elbit. Other participants, including entities that had previously not been involved, also joined, such as the CIB network that had operated on other political issues and the Choose Life Project channel. Figure 7 shows the beginning of the coordinated campaign with the submission of the petition on January 15, 2024.

We do not have information on the mechanism of coordination between all of the bodies active in the operation as well as details of the operational planning process. It is not known whether representatives of the participating groups led the planning or if other undisclosed entities were involved. The initial activity of the CIB network on the issue of Elbit was observed roughly two weeks before the petition was launched, suggesting that this period may have been used for planning and preparation. Figure 7 highlights the spikes in coordinated activity by these accounts on peak days of the campaign.

Figure 7 Timeline of the Campaign Promoted by Japanese Users

Method of Operation

The operation demonstrated many salient characteristics of effective and directed influence efforts. Key characteristics include successfully identifying a clear and measurable operational achievement that can be attained by exerting leverage on a defined target audience. Other characteristics include a well-defined operational strategy, such as synchronized action among all the participating bodies and the use of a wide array of tools, such as media (both controlled and external), field operatives, and CIB networks on social media. All these operated in a coordinated, continuous manner until the operation’s aims were achieved.

The components of the operation were as follows:

Digital Petition on the Global Platform Change.Org.[23] The digital petition was launched on December 20, 2023, by the group Omou Palestine (Students and Youth for Palestine Association), seemingly in collaboration with BDS Japan. From that point forward, the Twitter account @Omou_palestine was exclusively dedicated to promoting the petition and calling on the public to sign it. It should be noted that the number of signatures did not grow significantly. This suggests that a user recruitment mechanism—human or otherwise—was in place already from the planning stage and that this was not a natural organic awakening of public interest.

Holding a Press Conference. With representatives from Omou Palestine, BDS Japan, and NAJAT, a press conference was held on January 15, 2024, to present the petition. During this event, held at an undisclosed location, 24,793 signatures were presented, which is, curiously, the same number submitted during the registration on December 20.

Figure 8 The Press Conference

Demonstrations in Front of the Offices of the Japanese Companies. Demonstrations were held outside the offices of the companies Itochu and Nippon, accompanied by the creation of additional propaganda materials, primarily by the Choose Life Project channel, which also served as the campaign’s content hub. These demonstrations and the materials produced aimed to pressure the companies’ management, increase media exposure, generate video materials for the continuation of the campaign, and collect signatures for the petition. The main demonstrations took place on January 15 and 19, 2024. Figure 7 shows the intensive and coordinated operation of the suspicious network and the Choose Life Project’s channels during this time.

Targeted and Intensive Promotion of the Petition. The Choose Life Project channel, along with users involved in the CIB network, carried out targeted and intensive promotion of the petition through press conferences and demonstrations. This included coordinated exposure campaigns involving numerous shares, posts, and replies on the days of the physical demonstrations outside the companies’ offices.

Direct Pressure on the Companies’ Management. Direct pressure was also applied to the management of the two Japanese companies during the January 15 demonstrations. Participants in the campaign presented hard copies of the petition to management at the two companies, delivering them directly in front of their offices and before an audience (Figure 9). On the same day, a similar attempt was made to hand the petition to a representative of Itochu, but he refused to accept the petition “for security reasons.” Both events were accompanied by intensive, coordinated activities by all the participants in the campaign to maximize the event’s exposure. Videos documenting the meetings with Itochu’s management were posted on X (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Physical Action Vis-à-vis the Companies’ Management

The wording of the petition is carefully tailored to resonate with the particular sensitivities of Japanese audiences, highlighting Itochu’s and Nippon’s partnership with an Israeli company allegedly involved in human rights violations. The petition mentions the planned dates for its submission and the physical demonstrations on January 15 and 19, reflecting clear operational planning and not spontaneous, unmanaged activity. The petition page also features photos of one Omou Palestine volunteer who was identified as being present at both the press conference and during the physical submission of the petition to the company’s management.

The Results of the Operation

This case demonstrated coordinated activity by Japanese BDS groups, internal Japanese political bodies, and a CIB network operated by an unidentified confidential entity. The operation had a defined goal of canceling the collaboration agreement between Itochu, Nippon, and Elbit, signed in March 2023, by leveraging the public sensitivity surrounding the war in Gaza and the special sensitivities of the Japanese.

It is unclear whether the campaign’s planning was influenced by the proceedings at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague. The campaign began on December 15, before South Africa’s submission of a genocide complaint to the ICJ on December 29. It seems there is some connection to the British campaign described earlier, as it aimed to expand into international activity through global BDS organizations. However, the Japanese operation does not appear to be a subsidiary organization of Palestine Action UK. Unlike Palestine Action UK’s exclusive emphasis on direct action and vandalism, this campaign targeted Itochu’s management through coordinated pressure tactics.

It is impossible to attribute Itochu’s decision to withdraw from the agreement solely to the influence operation described or to assess its relative impact on the management’s considerations. In its official response, the company cited only the January 26 decision by the court in The Hague, without mentioning other factors. While the influence operation was certainly among the pressures surrounding the cancellation, the decisive factor or primary reason for Itochu’s decision remains unclear. The Japanese press coverage at the time highlighted the protests against the company’s management as a contributing factor, in addition to a boycott of other companies owned by Itochu in Muslim countries following October 7.[24]

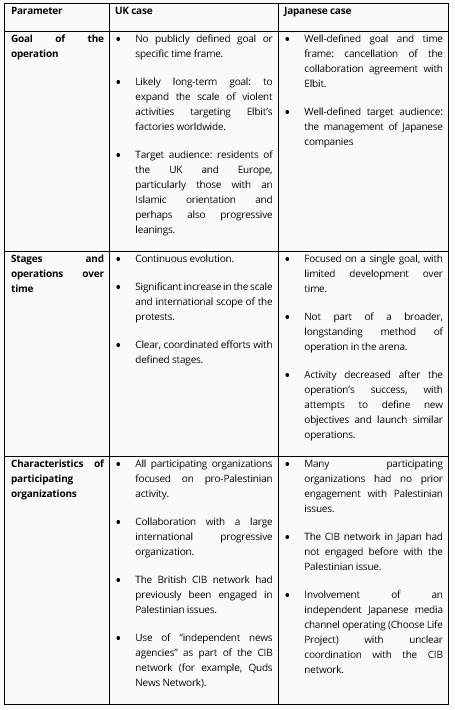

Table 1 presents a comparison of the main characteristics of the two operations. The comparison is based on three key criteria: the goals of the operations, their development over time, and the characteristics of the participating organizations. These criteria aim to identify and analyze patterns of activity to better understand the phenomenon and to illustrate the role of the CIB networks within each operation.

Table 1 Comparison between the Two Case Studies and Discussion of the Operations’ Characteristics

Cfir

Cfir

In their 2019 article, Shahar Eilam and Shira Patael describe the campaign of the network of BDS organizations as a long-term “war of attrition” aimed at achieving strategic objectives through concerted short-term tactical efforts.[25] The method of operation of hostile organizations involves collaboration within non-hierarchical networks of organizations across the international arena, forming local alliances to execute these tactical efforts. This operational pattern is apparent in the case studies presented in this article. Both cases analyzed highlight the collaboration of three kinds of entities: (1) activist organizations hostile to Israel that engage in on-the-ground activities (such as demonstrations), (2) CIB networks active on social media platforms and operated by various actors, and (3) organizations without a clear anti-Israel agenda but that align with the activities and cooperate with them.

In the Japanese case, the operation achieved a successful outcome within two months (although, as stated above, causality cannot be determined), after which the CIB network activity declined. However, the organizations involved continued to promote messages about ongoing objectives and additional activities in Japan. In contrast, the UK operation had multiple stages and did not produce a clear successful result. The first stage concluded without causing significant damage to Elbit but appeared to meet its presumed objective of significantly increasing media exposure and the organization’s number of volunteers and followers. In the second stage, possibly informed by lessons from the first stage, the operation reached another peak in its exposure with an international day of demonstrations in cooperation with a major progressive organization and supported by well-known public figures from the main progressive movement.

These operations seem to have many stages and coordinated tactical efforts over extended periods. While it is difficult to predict whether each stage or concerted effort will be successful, the cumulative achievements and the iterative learning over time create opportunities for breakthroughs. These arise when targeted activity, operational plans, and environmental conditions are suitable, and the target audience is ready.

A new and interesting phenomenon observed in both cases is the complementarity and synergy between activist organizations and CIB networks. Activist organizations focus on physical actions within their operational arena, but their numbers are often limited. As a result, they rely heavily on social media platforms to achieve public visibility. The exposure gained on social media platforms serves two purposes: to influence target audiences to partake in specific activities (such as demonstrations) and to expand the organizations’ outreach infrastructure by increasing the number of followers, supporters, volunteers, and activists. In contrast, CIB networks are designed to shape and mobilize public opinion in the digital space. They can complement and amplify the actions of activist organizations by effectively targeting and distributing messages to their audiences. This cooperation may be explicitly coordinated as part of a deliberate influence operation, as appears to have been the case in Japan. Alternatively, a CIB network may independently identify activist activities that align with its objectives and choose to promote them online without direct collaboration.

In both cases, social media news channels presenting themselves as independent were identified as operating in close cooperation with the CIB network. The activity of such accounts is a well-known component of the methods of the CIB networks. Their primary function is to produce content intended for specific segments of the population and to disseminate messages in a targeted and credible manner when needed. Monitoring such channels over time provides insights into the evolving objectives of online influence campaigns and can serve as an early warning for emerging threats.

Conclusion and Initial Directions for Addressing the Situation

The current international climate enables hostile organizations to identify achievable operational goals and simplifies their efforts in pursuing them. CIB networks on social media platforms provide the infrastructure to influence specific target populations, offering broad exposure in a short timeframe. In both cases discussed, the coordinated use of digital platforms was central to effectively disseminating messages and likely to achieving the objectives of these hostile organizations.

The integration of CIB networks into social media platforms has become a core capability for many states, armies, and organizations.[26] This enables groups such as BDS organizations to leverage resources from external actors to enhance their activities. However, the reliance on CIB networks as a main element in influence operations also presents an opportunity: their distinct network and behavioral characteristics make them identifiable, allowing for the tracking of their activity over time and possibly providing early warnings of an emerging hostile operation. For example, monitoring the Japanese CIB network might have provided early warning of its engagement with the Elbit issue days or weeks before the petition was launched.

Influence operations share similarities with cyber threats, particularly in their use of digital infrastructure. Like cyber threats, these operations rely on technological methods to maintain secrecy and to distance themselves from their targets while using active accounts and command-and-control (coordination) infrastructure. The tools and responses to such operations are in the early stages of design and formation, much like the initial development of cyber defense in previous decades.

As in cyber defense, addressing hostile influence operations requires collaboration among many national agencies, civil society, and private sectors.[27] One key conclusion from previous studies on this topic is that the State of Israel needs a central coordinating body to facilitate cooperation and information-sharing across these sectors.[28] This body would provide a unified national perspective for tracking threats, prioritizing responses, and developing a common language for addressing influence operations. Methodological frameworks for sharing knowledge and using a uniform language on the topic have advanced considerably in recent years, and several existing platforms enable inter-organizational and international cooperation on this topic.[29]

Addressing influence operations targeting Israeli interests abroad presents complex challenges that must be managed in terms of the jurisdiction of the Israeli authorities as well as the adaptation of methods and responsibilities on a case-by-case basis. The influence operations discussed here involved several key components: activists who are citizens of the target arena (usually friendly countries), operators of the CIB networks who are based either in the target arena or in a third country, and actors engaging in the digital space with audiences from various countries, each with its own regulatory framework governing the accountability of social media operators. In light of this, Israel’s national toolkit should be adapted to handle legal channels, cooperate with foreign authorities, and coordinate with security and intelligence agencies.

In the following, we describe key response components that should be developed to address the threat of influence operations on several levels:

The Role of State Security Agencies

As in the field of cybersecurity, technological detection and monitoring capabilities of civil society organizations complement the intelligence-gathering and prevention capabilities of state security agencies and work in synergy. Intelligence gathering and prevention efforts should be managed, when possible, in accordance with the authorities of the various security agencies, depending on the operational arena. However, it is necessary to appoint a dedicated body responsible for coordinating the activities of various agencies.

In addition, state security agencies play a critical role in preventing and investigating threats, often collaborating with international partners. Their unique and central capability lies in attributing the CIB networks to the entities operating them and identifying the interests behind these activities. This ability to attribute actions is a key strength that the civilian sector lacks in acting against threats.

Connecting to Legislation and Regulation Mechanisms in the International Arena

As in cyber defense, addressing influence operations requires international collaboration and an understanding of the organizational and legislative structures in each jurisdiction. Familiarity with these mechanisms is crucial for enabling effective action and information-sharing to neutralize threats. We recommend that the coordinating body in Israel develop expertise and knowledge of the local mechanisms in the various regions to enhance cooperation in countering CIB networks and influence operations, especially those originating outside the targeted arena.

Many countries, especially in the European Union, have initiated legislative measures and established regulatory frameworks aimed at creating a more transparent digital environment that is free of manipulations. In both case studies presented, and likely in other scenarios, the entities involved in the influence operations often use networks in the local language to engage with target audiences, and sometimes these activities extend beyond harming Israeli interests to encompass a broad range of issues. Therefore, this overlap presents an opportunity for the State of Israel to align its efforts with local regulatory bodies to combat foreign or hostile actors operating CIB networks among local populations.

Most of the relevant legislation addresses regulating digital platforms, requiring them to assume responsibility for addressing harmful content and its dissemination, in addition to mandating action against manipulative attempts, including removing influence infrastructure by enforcing platform terms of use.[30] A prominent example is the European Digital Services Act (DSA), a comprehensive regulatory framework that includes both legislation and mechanisms for monitoring and collaboration between enforcement agencies across the EU.[31]

However, a significant challenge in harnessing these mechanisms is that the actions of hostile organizations do not always include explicitly illegal content, and CIB networks do not always operate within the same jurisdiction as their targets, blurring the lines of foreign intervention. As a result, more in-depth work is needed to identify violations of laws or platform terms of use on a case-by-case basis to effectively address these operations.

The Role of Civil Society

Governments and defense organizations face inherent limitations in countering influence operations in the digital realm, primarily due to the global and almost unlimited nature of distributing information in the modern era, as well as the emphasis on freedom of expression and individual liberties in Western societies. Therefore, much of the work to combat manipulation takes place in the civilian and business sectors. Both in Israel and internationally, many organizations are engaged in these efforts, ranging from conducting research and building knowledge to raising public awareness, advancing legislation, reporting and monitoring disinformation, fact-checking, and identifying fake content.

Collaborations between non-governmental bodies, academia, tech companies, and even private influencers already play a key role in addressing foreign intervention and disinformation on social media platforms. As Amit Ashkenazi emphasizes, such partnerships should be a cornerstone of Israel’s broader defense strategy.[32] To enhance this component, we recommend fostering dialogue and creating a platform for sharing information between security agencies, the defense sector, and civilian bodies active in this field. The main advantage of this collaboration is the ability to leverage advanced commercial technologies for detecting CIB networks and providing early warning of influence operations.

Building Resilience at the Level of the Individual Organization

Just as developing digital literacy and resilience among citizens is an important component of defending against foreign intervention, building awareness and preparedness within Israel’s security and business communities operating in the international arena is essential to counter efforts aimed at harming Israeli economic and security interests.

This process involves several key elements, such as connecting organizations and companies to networks that specialize in defending against influence operations and establishing mechanisms that can function effectively during crises. It is important for organizations to recognize that an “influence crisis” is akin to a cyber event and should be included among the events requiring crisis management. Proper preparation includes developing detailed response plans, creating necessary external interfaces, building an appropriate conceptual understanding within the organization, and adopting advanced technologies for detection, warning, and response.

______________________

[1] This article is part of a soon-to-be-published memorandum on foreign influence and interference as a strategic challenge. Some of the articles included will address this issue from the perspective of adversaries. Some will also examine foreign influence and interference during routine times as well as during the disruption of democratic processes, the deepening of social rifts, election campaigns, and wars. The articles reflect a connection between systemic understandings and the policy needed to address it, both in Israel and in Western countries. The memorandum concludes a joint project conducted by INSS and the Israel Intelligence Heritage and Commemoration Center (IICC).

[2] Dolev Cfir is a researcher in the Military-Security Research Program at the Institute for National Security Studies. Yochai Elani is COO at Next Dim, managing the company’s activity with its clients in protecting against negative influence activity in social networks.

This article is part of a memorandum on foreign influence and intervention as a strategic challenge, which will be published soon. The memorandum concludes a joint project of the Institute for National Security Studies and the Institute for the Research of the Methodology of Intelligence at the Israel Intelligence Heritage and Commemoration Center.

[3] We would like to thank the editor of the article, David Siman-Tov, for the initiative for the research collaboration, the meticulous guidance throughout (in the sense of “he who spares the rod hates his son”) and his contribution to the quality of the research in general and the writing of the article in particular.

[4] Ofer Fridman, “Defining Foreign Influence and Interference,” Special Publication, January 4, 2024, https://www.inss.org.il/publication/influence-and-interference/

[5] Erika Magonara and Apostolos Malarias, “Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) and Cybersecurity, Threat Landscape,” European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), 2022, https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/foreign-information-manipulation-interference-fimi-and-cybersecurity-threat-landscape

[6] Office of the Law Revision Counsel, United States Code, Title 50—War and National Defense, chapter 44, National Security, subchapter I-Coordination for National Security, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, 2024, https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:50%20section:3059%20edition:prelim)#sourcecredit

[7] Office of the Director of National Intelligence, “Updated IC Gray Zone Lexicon: Key Terms and Definitions,” National Intelligence Council, July 2024, 20319-A NIC-SG-2024,

[8] Eric V. Larson, Richard E. Darilek, Daniel Gibran, Brian Nichiporuk, Amy Richardson, Lowell H. Schwartz, and Cathryn Quantic Thurston, Foundations of Effective Influence Operations, RAND Corporation, 2009, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2009/RAND_MG654.pdf

[9] Nathaniel Gleicher and Oscar Rodriguez, “Removing Additional Inauthentic Activity From Facebook,” Meta, October 11, 2018, https://about.fb.com/news/2018/10/removing-inauthentic-activity

[10] 1st EEAS Report on foreign information manipulation and Interference threats (2023). Strategic communications task forces and information analysis (STRAT.2), https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EEAS-DataTeam-ThreatReport-2023..pdf

Rowan Ings and Renee DiResta, “How Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Continues on Social Platforms,” blog, Stanford Internet Observatory Cyber Policy Center, May 29, 2024, https://cyber.fsi.stanford.edu/io/news/how-coordinated-inauthentic-behavior-continues-social-platforms

[11] See its profile at @Pal_action, X (formerly Twitter), https://x.com/pal_action; and its website at https://palestineaction.org/

[12] Damien Gayle, “Charges Dropped Over Protest at Israeli Military Drones Factory in UK,” The Guardian, November 23, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/nov/23/charges-dropped-protest-israeli-military-drones-factory-uk-uav-engines

[13] Nadine Talaat, “‘Can You Stop Us or Will We Stop You?’ Inside Palestine Action: The Group Shutting Down Israel’s Largest Weapons Company,” The New Arab, February 11, 2022, https://www.newarab.com/analysis/palestine-action-how-shut-down-israeli-weapon-company

[14] Progressive International, Progressive International Declaration, https://progressive.international/declaration/en; Elizabeth Leier, “Introducing Progressive International —A Global Left-Wing Solidarity Movement,” Canadian Dimension, September 24, 2020, https://canadiandimension.com/articles/view/introducing-progressive-internationala-global-left-wing-solidarity-movement

[15] Progressive International (@ProgIntl), “Breaking: Today, Elbit Systems, Israel’s largest arms manufacturer, is being shut down around the world, (December 21, 2023). X (formerly Twitter), https://x.com/ProgIntl/status/1737757037436494293

[16] Reza Javardi, “’Elbit 8’: Palestine Action Activists Win Legal Fight for Disrupting Israeli Arms Trade,” Press TV, December 27, 2023, https://www.presstv.ir/Detail/2023/12/27/717123/elbit-eight-palestine-action-win-legal-fight-disrupting-israeli-arms-trade

[17] Juliana Liu and Chie Kobayashi, “Japanese Trading Giant Itochu to Cut Ties, With Israeli Defense Firm Over Gaza War” CNN, February 6, 2024, https://edition.cnn.com/2024/02/06/business/japanese-israel-gaza-war-itochu-hnk-intl/index.html

[18] Yuval Azulai, “Because of The Hague: Elbit Systems Misses Entering the Japanese Market,” Calcalist, February 6, 2024, [in Hebrew] https://www.calcalist.co.il/market/article/bylid1lsa.

[19] “Because of The Hague’s Ruling, Japanese Company Itochu Cuts Off Contact with Elbit,” Techtime, February 7, 2024 [in Hebrew] https://techtime.co.il/2024/02/07/elbit-134/

[20] Network Against Japan Arms Trade (NAJAT), https://www.facebook.com/AntiArmsNAJAT/

[21] @kojiskojis, X (formerly Twitter), https://twitter.com/kojiskojis

[22] Choose Life Project, X (formerly Twitter), https://x.com/chooselifepj; Choose Life Project website: https://cl-p.jp/

[23] “Itochu must cut ties with Israel,” Petition, Change.org, 2023, https://shorturl.at/exTt8

[24] Kim Kahan, “Japanese Company Itochu to Cut Ties With Israeli Weapons Firm,” Tokyo Weekender, February 8, 2024, https://www.tokyoweekender.com/japan-life/news-and-opinion/japanese-company-itochu-to-cut-ties-with-israeli-weapons-firm/

[25] Shahar Eilam and Shira Patael, “The Threat of Delegitimization of the State of Israel: Case Study of the Management of a Cognitive Campaign,” in The Cognitive Campaign: The Strategic and Intelligence Perspectives, ed. Yossi Kuperwasser and David Siman-Tov, Memorandum No. 197 (INSS and Institute for the Research of the Methodology of Intelligence, October 2019), https://www.inss.org.il/publication/the-threat-of-the-delegitimization-of-the-state-of-israel-case-study-of-the-management-of-a-cognitive-campaign/

[26] European External Action Service (EEAS), StratCom Activity Report (2021), https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Report%20Stratcom%20activities%202021.pdf; EEAS, Strategic Communications, Task Forces and Information Analysis (STRAT.2),1st EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats, (2023), https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EEAS-DataTeam-ThreatReport-2023..pdf

[27] National Cyber Security Center (NCSC), National Counterintelligence Strategy (2024), https://www.dni.gov/files/NCSC/documents/features/NCSC_CI_Strategy-pages-20240730.pdf;

“Tackling Disinformation: Information on the Work of the EEAS Strategic Communication Division and Its Task Forces,” EEAS, October 12, 2021,

[28] Inbal Orpaz and David Siman-Tov, “Iranian Foreign Interference and Influence in Social Networks in Israel,” Special Publication (Institute for National Security Studies, 2024), https://www.inss.org.il/publication/iranian-influence/; Amit Ashkenazi, “Guidelines for Israel’s Addressing of Foreign Influence in Cyberspace and Social Networks,” Special Publication (Institute for National Security Studies, 2024) [in Hebrew], https://www.inss.org.il/he/publication/israel-cyber/

[29] “DISARM Red Framework,” DISARM Foundation, https://www.disarm.foundation/framework;

Ben Nimmo and Eric Hutchins, “Phase-Based Tactical Analysis of Online Operations,” Working Paper, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2023, https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/202303-Nimmo_Hutchins_Online_Ops.pdf

[30] Ashkenazi, “Guidelines.”

[31] European Commission, “The Digital Services Act Package,” https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package

[32] Ashkenazi, “Guidelines.”