Publications

INSS Insight No. 1321, May 21, 2020

Hezbollah’s military capabilities, which have been built up over recent decades with the help of Iran, are the leading conventional threat facing Israel. Since the end of the Second Lebanon War in 2006, the organization’s capabilities have strengthened both quantitatively and qualitatively, and its rocket and missile arsenal has increased more than ten-fold. The common assumption is that neither Israel nor Hezbollah is interested in war and that they are mutually deterred from it. Nonetheless, the risks of escalation have not waned, and perhaps are even gradually increasing. A number of scenarios may lead to escalation, including: an Israeli or American attack on the Iranian nuclear program, which Hezbollah is meant to deter with its threat of major retaliation; an Israeli attack in Lebanon, for instance against Hezbollah’s “precision project,” which Israeli leaders have pledged to obstruct; Hezbollah’s military entrenchment in Syria and its buildup by way of that territory, and Israel’s efforts to stop it; or a possible escalation due to a localized incident along the Blue Line between Israel and Lebanon. Israel has directed much political and media attention to the precision project, including in the Prime Minister’s speeches to the United Nations General Assembly, as well as in the efforts to condition American assistance to the Lebanese army on the dismantlement of sites for converting rockets to precision missiles. At the same time, Hezbollah’s military operations along the contact line appear in the headlines only when there are unusual incidents, and ordinarily, only a limited response effort is directed at it beyond the operational level. However, Hezbollah’s military deployment and operations in southern Lebanon in general and along the Blue Line in particular entail significant risks of escalation, and these in turn demand concerted and consistent efforts to contain them and roll them back.

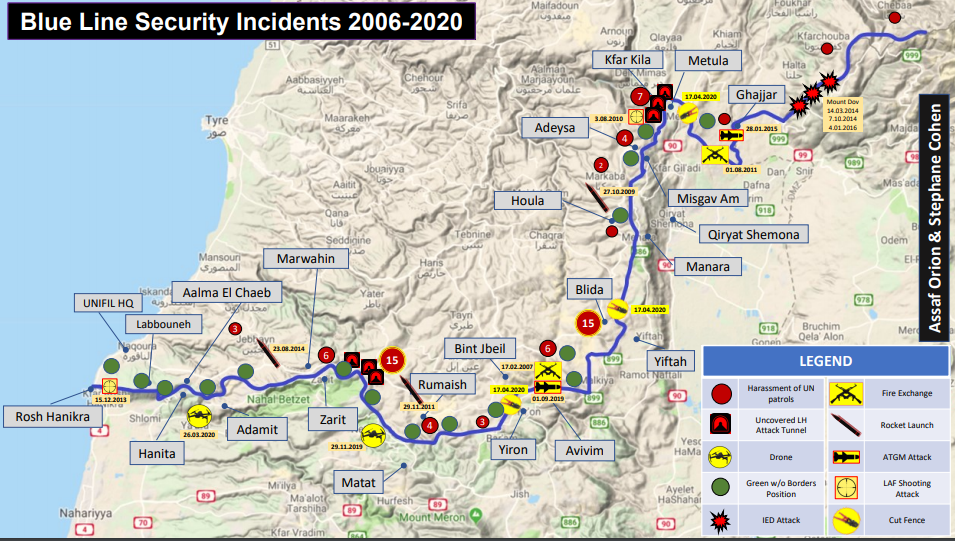

At the end of the Second Lebanon War (2006), the Security Council identified Hezbollah’s presence and activity in southern Lebanon as one of the causes of the war. Accordingly, Resolution 1701 sought to demilitarize southern Lebanon and remove illicit nongovernmental military capabilities by deploying the Lebanese army, supported by UNIFIL. In practice, however, Hezbollah in southern Lebanon has transitioned from its open military presence before the war (displaying arms and uniforms) to civilian cover after it; built up military infrastructures; undertaken reconstruction, rehabilitation, and buildup processes; and renewed and gradually even increased its military activity. Along the Blue Line, and sometimes across it, the organization routinely conducts close patrols by civilian-clothed groups with professional photographic equipment. Cloaked as a civilian forestry organization called “Green Without Borders,” Hezbollah has established at least sixteen observation posts alongside the border, and many other posts are operated from private homes. Homes and structures defined as “private property” were also used as the starting points for the attack tunnels project, meant to enable surprise and concealed penetration into Israeli territory beneath IDF border obstacles, placing Hezbollah forces behind IDF lines. This project was exposed by the IDF, and since the end of 2018, six tunnels crossing into Israeli territory were destroyed in Operation Northern Shield. The Hezbollah forces that were intended to move through the tunnels as part of the planned offensive on the Galilee are Radwan forces – high quality infantry forces that are deployed near the Blue Line and embedded in villages and the civilian environment, allowing Hezbollah rapid action into Israeli territory using a variety of methods. Hezbollah operatives systematically deny UNIFIL forces free access in the area, and most harassment actions against UN patrols are reported in the border area.

The escalation potential of Hezbollah’s deployment along the Blue Line can be deduced from the history of the sector since the IDF withdrawal from Lebanon, twenty years ago this month, and mainly from the years following the Second Lebanon War. Deployment near the border allowed Hezbollah to initiate and execute the kidnapping attack at Mt. Dov in October 2000, the attempted kidnapping from Ghajar in November 2005, and the kidnapping in July 2006 that precipitated the Second Lebanon War.

The contact line with Lebanon is also the area from which Hezbollah chooses to respond to Israeli attacks elsewhere in Lebanon or against its forces in Syria. Since 2006, sometimes in reaction to actions attributed to the IDF, Hezbollah has laid explosive devices along the contact line, mainly at Mt. Dov (Shab’a Farms). Following an IDF attack in the Syrian Golan Heights in mid January 2015, in which seven Hezbollah fighters and an Iranian general were killed, Hezbollah fired six Kornet anti-tank missiles from a location close to the Blue Line, killing two IDF soldiers on the slopes of Mt. Dov. The cumulative balance of casualties in the two incidents led to a limited IDF response. In late August 2019, Israel attacked a Quds Force cell in Syria, and two Lebanese nationals were among those killed. On the same day, there was a drone attack, also attributed to Israel, targeting a component of the precision project in the heart of Beirut. In early September, Hezbollah responded to the two incidents by firing three Kornet missiles from the border area toward an IDF facility in Avivim and a military vehicle near Yir’on. The missiles missed their targets by inches, and in the absence of casualties, the IDF again held back from launching a lethal or wide scale response, and made do mainly with firing smoke. On the night of April 17, 2020, the security fence was cut in three places, in response to an attack on a Hezbollah vehicle in Syria two days earlier. A columnist close to Hezbollah described some of the details of the operation in the al-Akhbar newspaper, calling it “readiness testing” for Israel by "knocking on doors of its border communities." He claimed that a daily security campaign is waged between the “occupation forces” and “the resistance,” whose fighters “are again deployed along the border itself, with their hands on the fence.”

Compared to the launch of a few rockets from farther away, accurate attacks from close range, such as explosive devices, sniping, and mainly anti-tank fire, have the most lethal potential during routine times. As such, they also have the greatest potential for leading to escalation, due to the direct link between Israeli casualties and the scope and lethality of the IDF’s response, and then between that response and the scale of the escalation on the part of the enemy's "response to the response." In addition, compared with operations in enemy depth, which are conducted under the close control of senior echelons, control of the operational response on the contact line is looser and more decentralized, down to the level of the individual soldier. It is not a coincidence that the two Kornet attacks were launched at moving vehicles that were in the field in contravention of sector command guidelines. The escalation dynamic is known, partly from experience in the Second Lebanon War, and also from incidents that took place in the Gaza Strip prior to Operation Protective Edge (2014). Despite the desire of both sides to avoid a wide scale conflict, when each side decides “only” on a limited operation, attack, or response, in practice it climbs another step on the ladder of escalation, which later turns out to have led to war.

Alongside the risks at the tactical level, Hezbollah’s deployment on the contact line increases the dangers of escalation to war on the strategic level as well. When escalation seems possible, it is often necessary to decide between a preemptive attack with its military advantages, and a delayed attack either to maximize the chances of avoiding an escalation or out of political considerations. Prior to the Yom Kippur War, Israel’s decision makers pondered the question of a preemptive attack on Egyptian forces before they began crossing the Suez Canal. They decided against it so that Israel would not be portrayed as the aggressor. Israeli decision makers may in the future be faced with a similar decision on Lebanon: avoid initiating or escalating operations in an effort to return to calm, or alternatively, assume that escalation is unavoidable, strike a preemptive blow against Hezbollah, and maximize the advantages of initiative and surprise. Hezbollah has the capability to launch a surprise attack by land into Israeli territory, which greatly increases the pressure on Israeli decision makers to decide upon a preemptive attack. In view of the risk presented by Radwan forces to Israeli border communities and the lack of depth between the threat and the targets to be protected, the considerations pushing for a decision on preemptive attack against the threat before it is realized gain in precedence.

Hezbollah deployment along the Blue Line, which has increased over time, therefore contains significant risks, both of escalation and in the fighting once it breaks out. Israeli policy in the “campaign between wars” must combine readiness for possible war, disrupting the enemy's buildup and slowing it down, reducing the threats to Israel should war break out, but no less important, dedicating significant efforts to prevent it. In parallel with its efforts against the precision project, Israel must strive to reduce the threat close to its northern border. At the operational level, Israel must document and expose the details of Hezbollah’s military deployment and operations near the Blue Line, and leverage that exposure to pressure the organization, its personnel, and those giving it cover, both in the villages and in the ranks of the Lebanese military and government. At the political level, UNIFIL forces should be demanded to focus their operations on a special security perimeter of 3–5 km depth along the Blue Line, and to condition the maintenance of its force (more than 10,000 troops) and budget (about half a billion dollars) levels on free access to any place within that perimeter. An effort is also required to dismantle the operational observation posts of the Green Without Borders organization, and to promote labeling it a terrorist organization. The practice of accepting “private territory” arguments as a pretext to prevent UN access must end, first to roads and open areas and then to buildings as well.

In addition, efforts should be made with the international community, with an emphasis on the United States and European countries whose position approaches that of Israel (compare Germany, which recently branded Hezbollah with all of its branches as a terrorist organization, with France, which stubbornly refuses to do so), in order to condition financial and military assistance to Lebanon on tangible progress in the security arrangements along the Blue Line. The deep economic crisis in Lebanon increases the dependency of the Beirut government and of Hezbollah on international assistance, and therefore empowers the international community’s leverage, in accordance with Security Council resolutions, to demand that steps be taken to lower the risks of war. In parallel, officials in the Lebanese government, military, security services, and local government should be labeled as terrorist supporters under sanction, insofar as they abet the continued prohibited military operations of Hezbollah along the Blue Line. Israel’s conduct with Hamas in recent years proves that it is possible to reach understandings and security arrangements in exchange for economic assistance even with a terrorist organization that is a bitter enemy. As the cost of war in Lebanon is much higher than the cost of war in the Gaza Strip, it is proper to exhaust efforts in a similar approach vis-à-vis Hezbollah, and even with greater intensity.