Publications

INSS Insight No. 1974, April 28, 2025

The risks to Israel’s economy have risen in recent weeks, along with the likelihood of a financial crisis in Israel. This is due to three events that occurred simultaneously: the end of the ceasefire in Gaza and the resumption of fighting, the approval of a problematic state budget for 2025, and political instability reflected in the dismissal of gatekeepers and the return of the judicial overhaul. All these raise many questions regarding the fiscal responsibility of the Israeli government in general, and the financing of the war in particular.

The risks to Israel’s economy have risen in recent weeks due to three events that occurred simultaneously: the end of the ceasefire in the Gaza Strip and the resumption of fighting, the approval of a problematic state budget for 2025, and the dismissal of gatekeepers and the return of the judicial overhaul. All these raise questions about the fiscal responsibility of the Israeli government in general and the financing of the war in particular.

The First Event: The Resumption of Fighting

The first event is the resumption of fighting, which took place in mid-March. IDF operations in the Gaza Strip and in Lebanon have also renewed the rocket threat on Israel and attacks by the Houthis from Yemen. Beyond the uncertainty accompanying this stage of the war and its objectives, it also hinders the functioning of the economy, which had begun to return to normal in the preceding weeks. For example, the return to fighting negatively affects economic growth in Israel due to the mobilization of reservists: businesses will again have to find replacements for those employees called back to reserves, and additionally, the expenses related to mobilizing reserve soldiers increase. A 2024 Ministry of Finance study found that the economic cost of a reserve soldier is approximately 48,000 shekels per month. In October 2024, the Governor of the Bank of Israel, Professor Amir Yaron, estimated that the economic cost of not drafting ultra-Orthodox men is about 10 billion shekels per year (roughly 0.6% of Israel’s GDP). The Bank of Israel Annual Report for 2024, published in March 2025, also states that it will not be possible to return to high-intensity fighting without significant steps, including further budget cuts and tax increases.

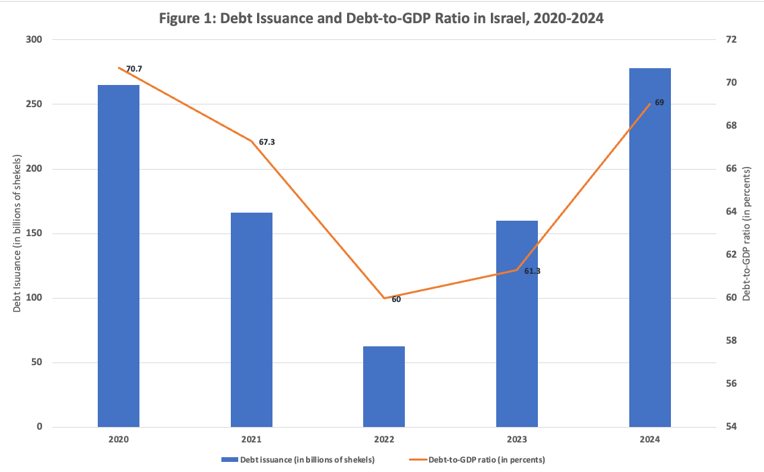

Figure 1 clearly shows that financing the war so far has required raising the debt in enormous amounts, even exceeding the debt raised during the COVID-19 crisis in 2020. Thus, debt raised in 2024 stood at 278 billion shekels compared to 265 billion in 2020. As can be seen in the figure, these borrowings, together with near-zero GDP growth, led to a significant increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio, from 60% in 2022 to 69% in 2024.

The Second Event: The Budget Undermining the Stability of Israel’s Economy

The second event destabilizing Israel’s economy is the approval in the Knesset of the largest state budget ever, amounting to approximately 620 billion shekels. On the face of it, passing a state budget should be a positive sign of political and economic stability. However, the approved budget represents a political achievement for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government but an economic failure for the country.

The Bank of Israel and the Ministry of Finance have repeatedly stated that the current government’s priorities do not align with the economic challenges facing the State of Israel. Therefore, it is not surprising that there is a significant gap between the recommendations of professional bodies for the 2025 budget and the budget that was actually approved. The budget places most of the burden on Israel’s working population, including increases in National Insurance contributions, freezing of income tax brackets, reduction of paid convalescence days, and an increase in VAT—all of which may harm demand levels in the economy. Additionally, it includes across-the-board cuts in education, health, and welfare budgets. In contrast, the budget lacks policies geared to promote economic growth, contains no significant cut to unnecessary coalition funds, and also excludes funds promised under the “Tkuma Law” for the rehabilitation of the communities along the Gaza border and in the north.

Instead of budgetary clauses that might encourage economic growth and the integration of ultra-Orthodox men into the labor market, the budget includes allowances as part of coalition agreements, which incentivize non-enlistment in the IDF and non-participation in the workforce. Furthermore, the allocation of funds to ultra-Orthodox educational institutions that do not teach core subjects perpetuates and worsens the problem, as the education they provide does not enhance their students’ future earning potential.

In summary, despite Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich’s December 2024 promise that the deficit would not exceed 4%, the planned deficit in the approved budget already stands at 4.9%. This follows two years in which Israel did not meet its planned deficit target due to the war: the deficit reached 4.1% in 2023 and 6.8% in 2024. All of this has significantly increased Israel’s debt-to-GDP ratio from 60% to 70% in a short time (see Figure 1). If the plan of the new IDF Chief of Staff, Eyal Zamir, to reoccupy the Gaza Strip is implemented, the deficit—and with it, the debt-to-GDP ratio—will rise sharply.

The Third Event: Political Instability and Its Economic Implications

The third event is political instability, marked by the return of the judicial overhaul and attempts to dismiss the attorney general and the head of the Israel Security Agency (Shin Bet). Since the outbreak of the war, three credit rating agencies have downgraded Israel’s credit rating. In each of their reports issued since the November 2022 elections, they have cited concerns over political instability and deepening polarization in Israeli society.

Over the past year, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich has predicted high growth for the Israeli economy after the war. He repeatedly criticized the rating agencies, claiming they are addressing non-economic issues. However, his argument contains a fundamental flaw: A vast body of economic literature shows that economic and political institutions influence a country’s growth and prosperity. For example, the 2024 Nobel Prize winners in Economics—Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson—demonstrated that countries with democratic institutions and a stable rule of law tend to prosper economically, while countries with weak institutions struggle to achieve meaningful long-term growth. This means that weakening the judicial power should affect a country’s credit rating even from a purely economic perspective. Therefore, rating agencies must consider political issues in every country they assess to evaluate potential risks to its economy. In essence, political instability contributes to rising debt financing costs, as evidenced by the increase in Israel’s risk premium in 2023—even before the war began.

The Cost of Political Instability: Rising Debt Risk

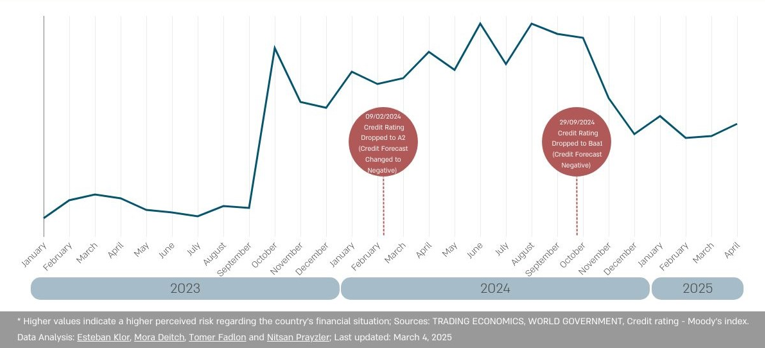

To better understand the impact of these three simultaneous developments on Israel’s financial resilience—as perceived by international investors—it is useful to examine fluctuations in Credit Default Swaps (CDS). This financial instrument serves as insurance against the risk of debt default. The higher a country’s CDS, the greater the perceived risk among investors regarding the country’s economic stability. As this index changes daily, it offers real-time insight into a country’s credit risk.

Figure 2 shows the CDS for 10-year Israeli government bonds (in US dollars) since January 1, 2023. It demonstrates that Israel’s CDS began to rise moderately at the start of 2023 and surged significantly with the outbreak of war. It continued a modest upward trend during the first year of the war. Following Israel’s successful operation against Iran in October 2024, the CDS dropped sharply. It continued to fall in November 2024 after a ceasefire agreement with Lebanon. However, with the renewal of fighting in Gaza in early March 2025, Israel’s CDS rose again. The practical implication of this increase is that the markets are pricing in a greater risk of default in Israel.

Figure 2. The Price of Credit Default Swap (CDS) Contracts for 10-Year Israeli Government Bonds

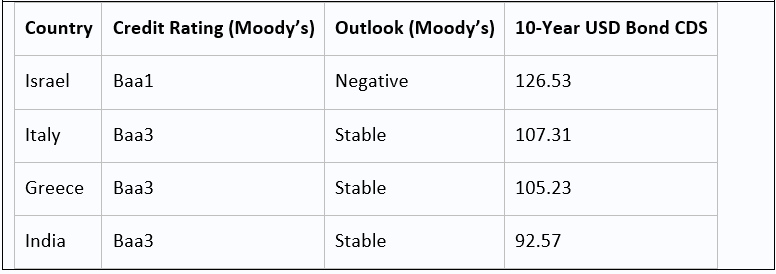

This index often precedes credit rating agency decisions. For example, Moody’s downgraded Israel’s credit rating in February and September 2024, well after the CDS spike. Overall, Israel’s credit rating by Moody’s dropped from A1 before the war to Baa1, with a negative outlook. This rating is very close to Ba1, a level at which bonds are considered junk status. A downgrade to this level could push Israel into a financial crisis, making it difficult to raise funds in the capital markets to finance its expenditures (including war expenses).

Table 1 highlights this danger and the possibility of further downgrades. The table compares 10-year CDS rates and Moody’s ratings across several countries. It shows that investors assess Israel’s bond risk as higher than what its official credit rating suggests. For example, Israel’s credit rating is higher than that of Italy, Greece, and India, meaning that according to Moody’s, Israeli bonds are less risky. However, according to CDS levels, Israeli bonds are viewed as riskier than those of these countries.

Table 1: Comparison Between Israel and Selected Countries

All data correct as of March 31, 2025.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the economic picture that emerges from the simultaneous occurrence of the three developments analyzed in this article is not promising. This is not to say that international markets should dictate Israel’s decisions in the realm of national security. However, it is important to emphasize that the country’s leadership must take into account that Israel’s national security is also tied to how it is perceived by the financial markets. From the perspective of the financial markets, Israel is in the middle of a security, political, and social whirlwind, and this is happening against the backdrop of trade wars and global economic uncertainty, largely stemming from US President Donald Trump’s economic policies. As a result of these trade wars, we are witnessing declines in global financial markets, and there are fears of a global slowdown or even stagflation in 2025. If these scenarios materialize, Israel’s economy will face far greater challenges. Therefore, Israel must pay close attention to the international financial institutions, act with increased caution during this period, and try to minimize the elements of uncertainty that cloud its economic outlook.