Publications

INSS Insight No. 1720, May 4, 2023

Key states in the region have recently demonstrated their clear preference for diplomacy and economics over the use of military and more coercive measures. Following a decade of armed struggles in various arenas, exhaustion has brought Arab and non-Arab states to work to thaw their relations, in order to improve their situation. This process, and its internal, regional, and global rationale, has implications for Israel in its struggle against Iran, its relations with the United States, and its normalization with Arab states.

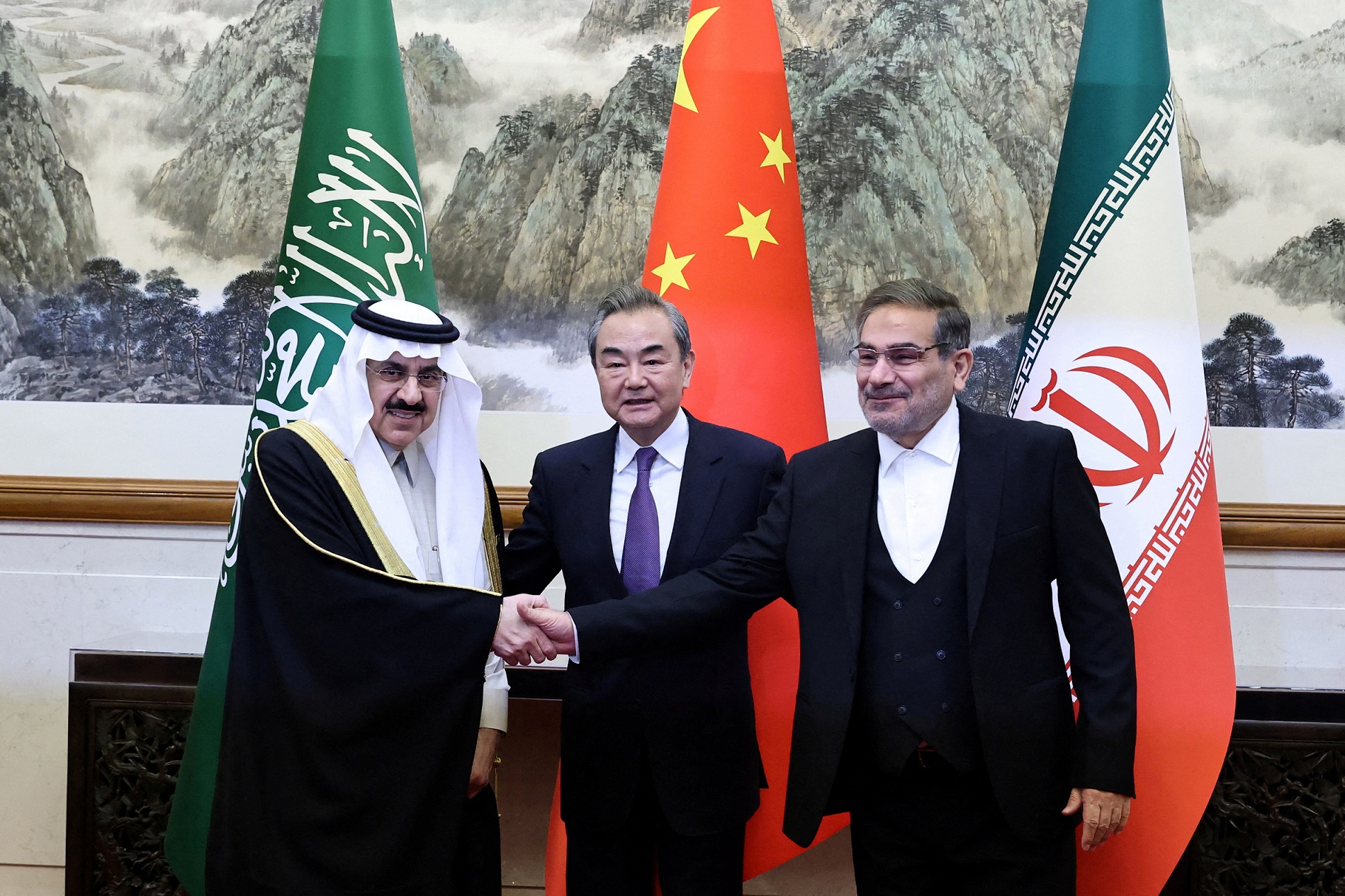

Negotiations between key Middle East states and non-state actors aimed at improving relations began several years ago. Some have recently borne fruit and produced new agreements, including the announcement of renewed diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, and gradually with Syria and Hamas; between Syria and Tunisia; between Qatar and its neighbors, and the gradual Turkish rapprochement with the Gulf states and Egypt. Syria may return to the Arab League after over a decade of a bloody civil war, and talks between Saudi Arabia and the Houthi rebels aimed at ending the war in Yemen have seen progress.

Regional actors seek to put behind them a decade of conflicts in various arenas, and are now choosing dialogue as a means to achieve national interests. This process appears to seek to reduce the level of hostility and to decrease tension, by prioritizing the use of diplomatic and economic tools over conflict and armed struggle. This regional sulha does not constitute a deep ideological or religious reconciliation, between Sunnis and Shiites, for example, but rather a sort of détente derived from cold interests and cost-benefit calculations, and primarily from the involved states’ deep need to improve their strategic positions. At the center of these dramatic processes are the improved diplomatic and economic relations within the Sunni Arab world and between Arab and key non-Arab states in the region – Turkey and Iran.

Underlying the Regional Détente

- Declining US influence in the region: Decreased attention by the United States to the security problems of its traditional Arab allies compelled them to try to improve their situation by themselves (self-help). Improved relations between the Gulf states and Iran, for example, are part of an ongoing attempt by the Gulf states toward strategic hedging; the same is true of the expanded footprint they now allow China and Russia. The latter seek to expand their influence in the region and reduce that of the US. For example, China was the mediator that facilitated the agreement to renew relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, and Russia was the mediator between Saudi Arabia and Syria.

- Directing attention to internal affairs: The Arab states are interested in narrowing external conflicts in order enable better responses to urgent domestic issues. In the poorer states, such as Turkey, the primary issue is the need for economic reconstruction, while in wealthy oil states there is a clear desire to complete projects, some of which are megalomaniacal, that rulers see as important for their long-term prosperity and stability.

- Iran’s enhanced strength and consolidation of its nuclear threshold status: The threat from Tehran led Iran’s neighbors to draw closer to it gradually, based on the idea of “keep your enemies close,” and recognition of its strength and its potential deterrent umbrella. Their moves were also grounded in the understanding that the attempt to stop Iran using diplomatic means has ceased, at least temporarily, and they seek to avoid an escalation of tensions. Some, especially the Gulf states, also fear a potential confrontation between Iran and Israel. By improving relations with Iran, they seek to distance themselves as much as possible from a potential regional military conflict that would be likely to harm them.

- The internal situation in Israel: The unfolding internal situation in Israel, with its attendant social and political instability, is seen by Israel’s friends and enemies alike as a source of weakness, and as a phenomenon that makes it a less attractive partner for collaboration. The tension between Israel and the US administration is also understood as a sign of weakness. This perception of Israel at the present time, compounded by Israeli government policy on the Palestinian issue, has caused a certain cooling effect on the normalization process and makes it difficult at the moment for Israel to draw other Arab and Muslim states into that process.

Reduction of regional tensions and cessation of bloody conflicts contribute to regional stability and therefore, in and of themselves, match Israeli interests. A stronger Saudi Arabia and an improvement in its security situation, for example, are in Israel’s interest, given that the two states share a similar view of strategic challenges in the region and have cooperated quietly for many years. Moreover, the establishment of diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran is not necessarily an impediment to continued gradual normalization with Israel: senior UAE officials, for example, claim that Gulf diplomacy with Iran does not endanger normalization with Israel. It is likely that Saudi Arabia, having somewhat secured itself vis-à-vis Iran and enjoying reduced tension in Yemen, will be able to continue the dialogue with Israel and the US regarding normalization. Furthermore, while improved relations between Tehran and its neighbors play into Iran’s hands diplomatically and economically, they do not necessarily give it increased freedom of action in the region. The series of agreements may also narrow the range of options available to Iran in the region and reduce its ability to operate proxies that harm its neighbors, given its substantially increased obligation to maintain proper relations with neighboring countries.

However, other processes concurrently underway in the region, including declining US influence and other noteworthy aspects of the rapprochement between Arab states and Iran, do not converge with Israel’s interests. In light of the new Arab image of closeness toward Iran, Israel may find it more difficult to promote the narrative that there is significant correspondence between the interests of Israel and the “moderate” Arab camp, as well as agreement on shared methods of actions vis-à-vis Iran. Furthermore, the new reality, within which actors formalize their relations with Iran in spite of Tehran not compromising on its “natural right” to full control of the nuclear fuel cycle, and its acceptance as a “semi-nuclear” state, one decision away from a nuclear weapon, is a dangerous precedent. Saudi Arabia will likely demand that the US also recognize its own nuclear capability as a condition for normalization with Israel.

A stable security reality in the region under Iranian nuclear deterrence will lead to a demand that Israel accept this new reality and not seek to change it. In other words, Iran will not present a nuclear weapon, and Israel will not act against it. The more Arab relations with Iran improve, the greater the pressure on Israel will be to walk back from its threat to attack Iranian nuclear installations, and the wider the possible gap will be between Israel’s stance and that of the Gulf states. States like Saudi Arabia will be able to turn a blind eye as long as Iran does not cross the nuclear threshold, without going down the nuclear military path themselves.

The instrumental rapprochement is also likely to lead to increased pressure by Tehran on the Gulf states not to enhance their relations with Israel. Iran has publicly expressed its opposition to the Abraham Accords and is trying to drive a wedge between Israel and its Arab neighbors. For their part, the Gulf states are hedging their risks and seeking to maintain proper relations with all sides, as a way to best pursue their interests to keep their options open. There may be some harm to the public nature of relations with Israel, as Iran will likely level additional pressure on these states. The agreement in Yemen also stands to cause Riyadh to feel safer and to have less need for Israel. However, it is not likely that the Gulf states will harm their quiet security relations with Israel, given that Iran was and remains the central threat against them, and that in this context, Israel is still perceived as an asset.

Conclusion

The process of reducing tension between the Sunni states in the region and between them and Turkey and Iran derives from preferencing regional-national interests over global and pan-Western interests. US policy in the region allows China to expand its footprint. The more China is involved, the more Chinese global relations (including the Belt and Road Initiative and the Global Security Initiative) invite a connection between regional actors. Israel is eager to be a part of a new “moderate” Sunni regional bloc; however, this development is currently in question. It appears that the Arab world has accepted, if reluctantly, the new regional reality at whose center is acceptance of Iran as a nuclear threshold state. This does not entail a rejection of Israel but is clearly a problematic turn of events for Jerusalem.

Israel must thus keep itself on the playing field – continuing to strengthen relations with Gulf states and maintaining and strengthening its peace agreements. To the extent that Israel can rebuild its image of strength and stability, it will continue to be relevant in the region. Accepting a negotiated compromise about the judicial overhaul advanced by the Israeli government will strengthen the country’s social resilience and cohesion and reduce tensions between the government and the US administration. Immediately thereafter, Iran’s achievements in the region should be overlooked and a joint push made with the United States to strengthen and expand the normalization process, with a primary focus on the kingdom of Saudi Arabia.