Publications

INSS Insight No. 929, May 15, 2017

The “Memorandum to Create De-escalation Zones in Syria,” signed in Astana, Kazakhstan on May 5, 2017 by Russia, Iran, and Turkey as guarantors of implementation, is the fourth attempt within just over a year to bring about a sustainable ceasefire in Syria. New this time is the establishment of four de-escalation zones in Syrian territory. The agreement is thus an attempt to shape the future in Syria, including areas where Israel and Jordan have very clear interests, yet thus far without consideration of these interests. As such, it creates the potential for the emergence of substantive new threats. At the same time, it serves as another signal to Israel to reconsider its policy of non-intervention in the crisis in Syria and display strong resolve to protect its essential interests.

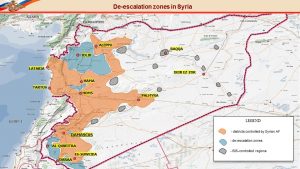

Map of the De-escalation Zones published by the Russian Defense Ministry (CC BY 4.0)

Map of the De-escalation Zones published by the Russian Defense Ministry (CC BY 4.0)

On May 5, 2017, against the despair and pessimism that has surrounded the repeated attempts to solve the six year crisis in Syria, the "Memorandum to Create De-escalation Zones in Syria” was signed in Astana, Kazakhstan. The agreement, signed by Russia, Iran, and Turkey as guarantors of implementation, is the fourth attempt within just over a year to bring about a sustainable ceasefire in Syria. New this time is the establishment of four de-escalation zones in Syrian territory. The first and largest zone includes Idlib province and certain parts of the neighboring provinces in northern Syria, close to the Turkish border, home to some one million civilians and where several opposition groups are concentrated. The second zone is the enclave between Hama and Homs, with about 200,000 residents. The third zone is the enclave to the east of Damascus, with about 700,000 people. The fourth zone in southern Syria covers parts of the Daraa and Quneitra provinces, which are adjacent to the Israeli and Jordanian borders and are home to some 800,000 people.

The stated purposes of the agreement, which came into force the day after it was signed, are to reduce the intensity and extent of the fighting; relieve the humanitarian distress to the extent possible; and enable refugees to start returning to Syria. Above all the goal is to lay the foundations for a comprehensive solution to the crisis, while maintaining Syrian unity (and from Russia's perspective, to prepare the ground for a federal structure). Thus, under the agreement, for six months with an option of extension, fighting between the regime and the armed opposition in the four de-escalation zones will be forbidden, including activity by the Syrian Air Force. However, the war will continue in these safe zones, as throughout Syria, against the Islamic State, Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham [Jabhat al-Nusra], and other terrorist elements identified with Sunni-Jihadi Islam. In addition, humanitarian aid will be brought in and public services such as supplies of water and electricity will be renewed by the government, and conditions will be created for the voluntary return of refugees and displaced persons. Military forces from the three guarantor states will be deployed at checkpoints and observation posts around the safe zones, to supervise implementation and enforcement of the agreement.

Missing from the parties to the agreement are the Syrians themselves: although the Assad regime announced that it will observe the terms of the agreement (excluding external third party supervision), there is no guarantee that it will keep its promise. For its part, the Syrian opposition opposes the limitation of the ceasefire to only portions of the country, and has firmly ruled out formal recognition of the role of Iran, which it sees as "putting the wolf in charge of the sheep." Moreover, the opposition has called for the necessary involvement of the United States and the Sunni countries, above all Saudi Arabia, who were noticeably absent from the Astana process. (A United States representative attended the talks, but was not an active participant.) Perhaps the May 10 meeting in Washington between President Trump and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov signals its possible return to the picture).

Throughout the years of the civil war in Syria, Israel has taken a position of non-involvement, except to prevent attacks on itself and the transfer of advanced weapons to Hezbollah. However, the Russian initiative reinforces the need to review this policy, because the latest move represents a new phase in shaping the future of Syria, including both challenges and risks on several levels.

At the regional and superpower level, the absence of the United States from the agreement framework leaves the task of shaping Syria's future in the hands of Russia, Iran, and Turkey (with its problematic stance toward Israel), while Israel's security interests are without any suitable representation.

At the military-security level, the agreement gives Iran, to the extent that this depends on Russia, an official and recognized status in any future Syria and the legitimacy to establish a military presence in the country. This conflicts sharply with the position of the Syrian opposition and with the red lines set by the United States and Israel on this matter. According to the agreement, Iranian forces will take part in supervision and enforcement, which will validate Iran’s deployment on Syrian territory while using "all means necessary" for that purpose. At this stage, details are not entirely clear, including the question of participation by Iranian forces in supervision of the de-escalation zone adjacent to the Israeli border.

At the local level, a risk posed by the agreement is the gradual return of the Assad regime's forces to areas where they are not currently in control, under the pretext of restoring basic services to the de-escalation zone. This development could increase the dependency of the various zones on the regime and strengthen Assad's local influence, while the regime will gain breathing space to rehabilitate the army and build up its strength. In the absence of external aid to reinforce the defensive abilities of the local forces, and with no improvement in the economic and social conditions of the local population, the de-escalation zones could quickly find themselves at a disadvantage, exposed to the regime's efforts to return to the helm along with its allies hostile to Israel.

The return of refugees and displaced persons to the safe zones is another complex and challenging issue. Their return to areas of destruction, without the means to absorb them, could degenerate into a severe humanitarian crisis, with consequences for the internal Syrian situation as well as for neighboring countries, including Israel and Jordan.

At the tactical level, the announcement of the cessation of fighting between the regime and the rebels while the fight against terror organizations continues, is expected to lead to further attacks on rebels and the general population by Assad and Russian forces on the pretext of fighting terror organizations, as occurred under previous ceasefire agreements.

To avoid the negative developments and unilateral shaping of tomorrow's Syria by the Russian-Iranian axis, Israel should act on two parallel levels: one, display resolve toward Russia and continue to project strength and power to undermine Russian efforts in the region, in order to retain its bargaining chips; and two, encourage the United States, Jordan, and the Gulf states to be more involved in the strategic discussions on resolving the Syrian crisis, and promote the following principles:

- No agreement can be reached without the involvement of the United States and the Gulf states, in order to insure a balanced picture of interests in Syria.

- Observance of Israel's "red lines," which are based on preventing Iran and Hezbollah forces from getting a foothold in southwest Syria, and particularly the Golan Heights, and banning the use of Syrian territory for transferring weapons to the Hezbollah.

- Arrangements regarding the border areas must be made in conjunction with the neighboring countries. Just as Turkey is a party to the arrangements affecting northern Syria, Jordanian and Israeli interests must be considered in southern Syria.

- Possible expansion of the UNDOF mandate as the body responsible for supervising and stabilizing the area and assisting the local population.

- Local pragmatic forces will be organized with regional and international support into effective combat frameworks, with joint training programs, equipment, and arms, both to defend civilians and to fight jihad terror organizations in the arena.

- Western countries and international organizations, with the support of neighboring countries and Israel, will work to strengthen their ties with the local population in southern Syria to send humanitarian aid and support efforts to rehabilitate and develop the safe zones, giving them some independence in areas of energy, housing, food, agriculture, education, and health.

- Quotas and stages for receiving refugees will be defined according to the success of rehabilitation, with control and review mechanisms.

- A mechanism for joint coordination with Israel, Jordan, and the United States will be established that will reflect a joint strategy both for the talks on the arrangements in Syria and regarding the military and civilian efforts in southern Syria.

The de-escalation regional agreement is an attempt to shape the future in Syria, including areas where Israel and Jordan have very clear interests, yet thus far without consideration of these interests. As such, it creates the potential for the emergence of substantive new threats. At the same time, it serves as another signal to Israel to reconsider its policy of non-intervention in the crisis in Syria and display strong resolve to protect its essential interests.