Publications

INSS Insight No. 913, April 4, 2017

The Revolutionary Guards’ expanded involvement in infrastructure and development projects throughout Iran is highly evident. However, the lifting of the economic sanctions following the implementation of the JCPOA provides an opportunity to reduce Revolutionary Guards involvement in the economy by means of encouraging foreign companies to invest in Iran once again. Indeed, the corps is well aware of the challenges it faces following the nuclear agreement that endanger the organization’s economic interests. However, it feels the need to control the state economy not only to finance its own activities in Iran and beyond, but also to solidify its political status, and hence the group’s increased efforts to entrench its involvement in development and infrastructure projects. This trend has some serious ramifications: at the economic level; politically; and socially, by deepening the organization’s penetration into society while serving security interests related to regime stability.

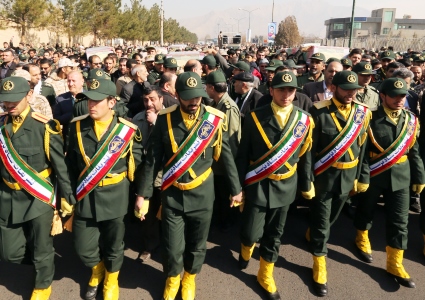

In mid-February 2017, Mohammad Ali Jafari, commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), attended a ceremony inaugurating the first stage of a project to establish two subway lines in Mashhad, a city in the northeast of Iran. Also in attendance were Ibrahim Raisi, a senior cleric in charge of Imam Reza Foundation in Mashhad and named as a possible successor to Supreme Leader Khamenei, local government officials, and Abdollah Abdollahi, the head of the IRGC construction corporation Khatam-al Anbiya, responsible for the project. During the ceremony, Abdollahi announced that the corporation “set new records” by completing the first stage of the project in only 33 months, and when speaking with journalists, he stressed that Khatam-al Anbiya works in cooperation with the government, which defines the organization’s priorities and authorizes the engineers to advance the projects, particularly in the field of construction. Similarly, in a visit to the Sistan-Balouchistan province in the country’s southeast just prior to the event, Jafari announced that the organization’s development efforts in the province, considered one of Iran’s most backward areas, would continue over the next few years as per the instruction of the Supreme Leader to ease plights throughout Iran.

In early March, Jafari likewise announced the IRGC’s intention of expanding the organization’s involvement in agricultural development so as to help the “resistance economy” announced by the Supreme Leader, whose main goal is reducing Iran’s dependence on foreign elements and developing self-sufficiency. At a science and technology conference, Jafari said that the Revolutionary Guards will acquire locally made technological products as part of expanding the organization’s involvement in the agricultural industry.

The expansion of the Revolutionary Guards’ involvement in infrastructure and development projects throughout Iran may be seen in conjunction with the October 2016 declaration by the IRGC spokesman about its intention to begin building regional bases throughout Iran that would act to promote development projects in the provinces. He noted that the bases would be built based on the Supreme Leader’s decision to develop impoverished regions far from the center, would help improve public security in these areas, and would provide various services to the population. Jafari instructed the IRGC commanding officers in the provinces to exploit the know-how of Khatam-al Anbiya in building these bases.

Khatam-al Anbiya was established in 1989 at the Supreme Leader’s directive to help Iran reconstruct its economy and infrastructures, badly damaged during the Iran-Iraq War. The corporation is subordinate to the Revolutionary Guards, and its head is appointed directly by the commander of the IRGC. At present, it employs some 5,000 companies and contractors and more than 150,000 workers. Since its establishment, the corporation has been tasked with hundreds of large economic projects, with activity focusing on three major areas: energy projects, such as gas and oil field development, construction of refineries and oil storage depots, and oil and gas lines; engineering development projects, such as ports, tunnels, roads, railways, dams, water pipers, channels, and drainage systems, and projects in the mining industry; and anti-poverty projects, such as programs for developing backward regions, agricultural development, and the establishment of cultural, social, and religious centers in the nation’s periphery. In late December 2016, Iranian Defense Minister Hossein Dehghan said that dozens of key economic projects of national significance in oil, gas, transportation, dams, water supply, and communications are currently underway out by Khatam-al Anbiya. At present, the corporation is the spearhead of the IRGC involvement in the state economy, and based on various assessments, controls anywhere between 20 and 40 percent of the national economy.

In recent years, a growing number of Iranian voices have been calling for limiting the involvement of the Revolutionary Guards in the economy, and especially the role of Khatam-al Anbiya. According to critics, the corporation’s continued involvement in national economic projects perpetuates the private sector’s weakness and opens the door to corruption because of the tax breaks it receives and its direct subordination to the Revolutionary Guards, which prevents effective oversight and criticism. A report issued by the Majlis research center in January 2016 noted that the involvement of government and quasi-government institutions (a veiled reference to the Revolutionary Guards and large Iranian foundations under the regime’s control) managed by large economic companies is one of the primary factors jeopardizing foreign investments in Iran critical for economic development in the post-sanctions era.

By contrast, those favoring Revolutionary Guards involvement in the economy, headed by the leaders of the armed forces and the IRGC itself, claim that the organization’s involvement is necessary for Iran’s economic development, especially given the economic sanctions and the private sector’s weakness. While President Rouhani supports reducing Revolutionary Guards involvement in the economy, he too recognizes the need to continue to make use of the organization’s capabilities. In a speech to Revolutionary Guards commanders in September 2013, Rouhani called on the organization to continue to use its power and human and economic resources to help the government advance the economy. He rejected the claim that the Revolutionary Guards competes economically with the private sector, and noted that the organization’s participation in large national projects that cannot be carried out by the private sectors is indispensable.

However, the lifting of the economic sanctions following the implementation of the JCPOA provides an opportunity to reduce Revolutionary Guards involvement in the economy by means of encouraging foreign companies to invest in Iran once again. Reducing IRGC involvement in the economy in the post-sanctions era is seen not only as a necessary step in promoting structural reforms essential to the economy but also as an answer to the international community’s demand that Iran stop supporting terrorism via the Revolutionary Guards as a precondition for incorporating Iranian banks in the global banking system. Indeed, Iran’s efforts to take itself off the blacklist of the international Financial Action Task Force, which roots out money laundering and terrorist financing, resulted in the September 2016 decision of two local banks – Mellat and Sepah – to stop providing banking services to institutions associated with the Revolutionary Guards.

For its part, the Revolutionary Guard corps is well aware of the challenges it faces following the nuclear agreement and worries that the lifting of the sanctions will result in foreign companies entering the Iranian economy with the President’s blessing, thus endangering the organization’s economic interests. It needs to control the state’s economy not only to finance its own activities in Iran and beyond, but also to solidify its political status. Consequently, it is easier to understand the organization’s increased efforts to entrench its involvement in development and infrastructure projects throughout Iran. This trend has some serious ramifications: at the economic level, it could make it difficult to realize the reforms necessary for Iran’s economy, which suffers from severe structural flaws, particularly over-centralization and corruption; politically, it could help the Revolutionary Guards retain great political power in Iran’s internal balance of power, primarily vis-à-vis the President; and, when it comes to security, it could lead to increased presence throughout Iran, especially in the periphery, and deepen the organization’s penetration into society while serving security interests related to regime stability.

Alongside the benefits to the Revolutionary Guards from the growing involvement in the economy, the trend is rife with risk. Although economic activity is ostensibly managed separately from military and operational tasks, the involvement of the organization’s top leadership in large economic projects might affect their ability to focus on core missions and in turn, damage operational efficiency. Moreover, the more the IRGC involvement in economic projects grows, the greater the danger it will lead to increased corruption, which is a major flaw in the Iranian economy. This might erode the organization’s public image, which has already been tarnished because of the politicization of the Revolutionary Guards in recent decades and further the alienation between the public and the regime’s institutions.