Aircraft Under the Radar: Mechanisms of Evading Sanctions in Iran’s Aviation Sector

Danny Citrinowicz, Avishai Sober, Dor Huri, and Omer Bazia

A Special joint publication of the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) and ColEven

Despite being subjected to one of the harshest sanctions regimes in the world, Iran has succeeded in building a sophisticated, law-evading mechanism to support its aviation industry, which reflects the broader principles of the shadow economy it has developed. This article maps the operational architecture of that mechanism, based on using front and shell companies in countries with little transparency, layered ownership registries, bursts of activity designed to complete transfers within short timeframes, and flight-path planning that includes fictitious emergency landings to allow aircraft to quietly enter Iran. The article describes how Iran’s aviation sector—significantly harmed by sanctions—has shifted from a civilian transportation tool to a core component of the regime’s economic and security strategy, enabling it to continue functioning, finance its regional proxies, and project resilience in the face of international pressure. The aviation industry represents only one link in a much larger apparatus designed to evade sanctions in the trade of oil, gold, and dual-use technologies; yet the aviation sector clearly demonstrates the method: a sophisticated integration of state, market, and underground networks that operate in regulatory gray zones and disrupt efforts to globally enforce the sanctions.

Iran’s aviation industry has achieved independence and is ready to overcome the sanctions.

—Hossein Pourfarzaneh, head of Iran’s Civil Aviation Organization, May 23, 2025

For decades, the Iranian regime has contended with multilayered international sanctions imposed in response to its nuclear program, ballistic missile development, and support for terrorism. The American, European, and international sanction regime imposed on Iran includes a wide array of economic, financial, and technological restrictions. The sanctions imposed on Iran’s civil aviation sector are primarily designed to block the transfer of dual-use technologies that could serve the regime’s security organizations, and they constitute an integral part of the sanctions regime, representing one of the West’s most significant forms of pressure on Tehran.

The American sanctions, which are the broadest and most effective, are based on a combination of federal legislation and administrative regulations: the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act (IFCA), the Iran Sanctions Act (ISA), and Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), as well as regulations of the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) and those of the Bureau of Industry and Security. In addition to banning Iranian airlines from flying to a number of countries, this legal framework prohibits any sale, lease, maintenance, or transfer of aircraft or aircraft components to Iran, including indirect transactions through intermediary states or entities. The Export Administration Regulations (EAR) apply the de minimis rule, which stipulates that products manufactured outside the United States containing more than 1% US components are still subject to American regulation. The Foreign Direct Product Rule expands the scope of sanctions by determining that equipment based on US software or technology—even if manufactured in a third country—will be considered an American product for legal purposes.

In September 2025, the UN Security Council fully activated the snapback mechanism, reinstating all international sanctions that had been lifted from Iran under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear agreement in 2015. This move was preceded by the renewal of US sanctions following President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the nuclear agreement in 2018, and followed the decision of the E3 countries (Britain, France, and Germany) in August 2025, to activate the mechanism after determining that Iran was materially and continuously violating its nuclear commitments.

The sanctions have significantly impaired Iran’s ability to renew and upgrade its aircraft fleet. As a result, Iran has been compelled to pursue methods that at least allow it to sustain its aging fleet. The country’s size and its extensive reliance on aircraft for both civilian and military purposes have required the regime to maintain the aviation industry’s operational continuity despite the sweeping sanctions. Consequently, Tehran has consistently employed creative means to circumvent restrictions and smuggle spare parts and even entire aircraft that enable ongoing civil and military aviation activity. The critical importance of the aviation sector for the regime became evident immediately after the 2015 nuclear deal, when Iran sought to acquire aircraft from companies such as Airbus in an effort to modernize the fleets of its airlines.

Western states have identified Iran’s aviation industry as key to the regime’s weapons smuggling to its regional proxies (Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Syrian regime prior to its collapse, and pro-Iranian militias in Iraq) as well as to Africa (e.g., shipments of UAVs and weapons to Sudan) and even to Venezuela. This activity involves Iranian airlines such as Mahan Air and Qeshm Air, which the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) uses to transport weapons on ostensibly civilian flights. This understanding, combined with the fact that Iran’s aviation sector also provides vital internal connectivity across the country, has made the sector a major target of the sanctions regime. The prevailing assessment is that impairing Iran’s ability to operate its aircraft (primarily by restricting access to spare parts) would not only disrupt its capacity to move weapons worldwide but would also heighten the regime’s sense of isolation and undermine its public standing among Iranian citizens who depend on domestic airlines for travel within Iran and abroad.

The Iranian civil aviation sector has suffered heavily under these sanctions. As of 2025, it is estimated that approximately 60% of the passenger aircraft registered in Iran are grounded. The average age of Iran’s civil aircraft fleet is around 28 years—more than double the global average. Import restrictions and the lack of original spare parts have pushed airlines toward “cannibalization” to keep the planes operational. Without access to international insurance, conversion, and oversight services, Iranian airlines struggle to meet even basic safety standards.

Another major difficulty stems from restrictions on refueling Iranian aircraft in many countries. As a result, Iranian planes are often forced to carry excess fuel, which increases weight, raises operational risks, and significantly drives up operating costs. Lacking adequate logistical and maintenance support, Iranian airlines find it increasingly difficult to keep their aging fleets in service and must bear unusually high costs to operate aircraft that would have already been retired elsewhere. This situation has led to Iran’s greater dependence on smuggling networks and opaque aviation transactions, which now form an economic subsystem sustaining the regime as part of the broader “Iranian shadow economy.”

The evasion of sanctions in Iran’s civil aviation sector is not merely a legal challenge; it also has a clear security-strategic dimension. Airlines such as Mahan Air and Qeshm Fars Air effectively serve as an air-transport arm of the IRGC, operating under Unit 190 of the Quds Force, which oversees covert smuggling of weapons, equipment, and funds to terrorist organizations and Iran’s regional proxies. These airlines are used to transport weaponry, dual-use equipment, personnel, and financing to theaters of strategic importance for the regime worldwide, particularly the Middle East. The connection between these airlines and the IRGC extends beyond infrastructure and the civilian cover they provide and are also evident at the organizational level. Numerous findings indicate substantial structural-organizational overlap between airline employees, their senior officials, and the IRGC. As a result, the line between these companies’ declared civilian activity and their military-operational role is often blurred. This blurring in turn makes it difficult for enforcement and regulatory agencies to detect illicit activity in real time, creating an ongoing challenge for international monitoring mechanisms.

Methodology

This study provides an in-depth analysis of the acquisition and smuggling of civil aircraft into Iran between 2014 and 2025, excluding transactions conducted during 2016–2018, the period of sanctions relief under the nuclear agreement. The research methodology relies exclusively on open-source collection and analysis, including intelligence reports, credible media sources, and databases that track ownership records and transfers of civil aircraft, alongside up-to-date fleet data. Our examination of the ownership structures of the entities involved in acquiring and smuggling aircraft draws on local corporate registries as well as reliable media reporting.

Iran’s Smuggling Typologies

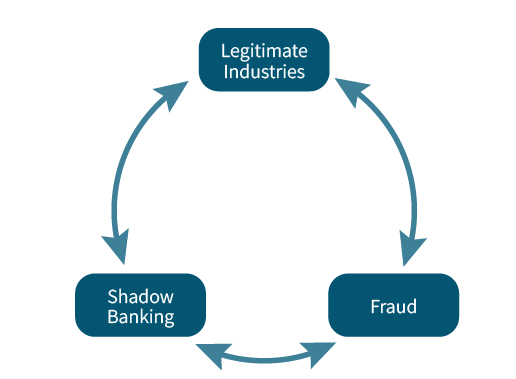

Iran’s smuggling network is structured as a triangle, with each of its three sides essential to its operation (see Figure 1). Although specific sectors, such as oil, weapons, and aircraft, differ in certain details, the underlying principles are the same.

Figure 1. Iran’s Smuggling Network Triangle

- “Legitimate” Commercial Industries

Iran relies on trade in global markets and industries viewed as lawful in order to generate state revenue. The most prominent example is the oil sector, large segments of which are subject to extensive sanctions.

- Corporate Fraud, Front and Shell Companies

In parallel, Iran operates an extensive system of fraud built on establishing and managing front and shell companies, using intermediaries, and creating formal ownership structures to sever the apparent connection between the Iranian entity and the corporate body. This creates a smokescreen that obscures true ownership and control.

- An Alternative Financial System—“Shadow Banking”

The third side of the triangle is a parallel financial system. Currency-exchange businesses, informal payment channels, Chinese banks, and various financial instruments provide front and shell companies with access to funding channels and the ability to move money around globally while minimizing exposure and bypassing Western regulations.

Smuggling Patterns and Transfer Mechanisms

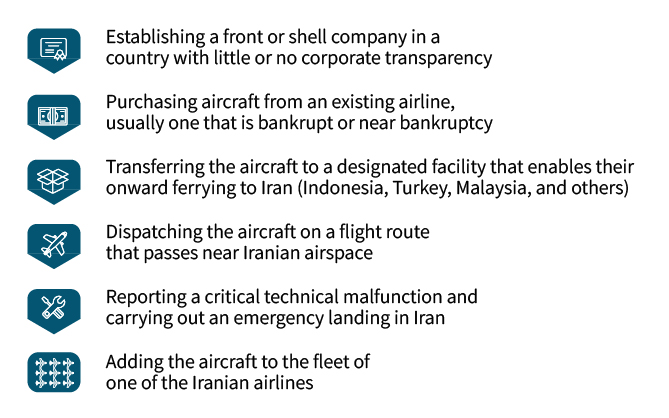

In recent years, the Iranian government and the IRGC have developed significant capabilities in transferring weapons and military equipment, as seen, for example, in the activity of Unit 190 of the Quds Force. However, the acquisition and transfer of passenger aircraft require a very different skill set from those previously developed by the Quds Force. As a result, Unit 190 was compelled to adapt its methods to purchase aircraft despite sanctions, store them safely, and then transfer them in a way that would avoid detection until the aircraft reach Iran (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Process of Smuggling Aircraft into Iran

Iranian smuggling typologies reveal several distinct operational patterns used to conduct these transfers. The first stage is the purchase of the aircraft, and this mechanism splits into two primary types of acquisitions: (1) purchases from states that permit trade with Iran and bypass the sanctions; and (2) purchases from states that publicly declare their compliance with sanctions. Transfers from Russia, China, or Iran’s regional allies are generally carried out directly, without the need for front or shell companies, due to extensive cooperation between these countries. By contrast, transfers from states that ostensibly adhere to international sanctions shed light on the methods Iran uses to move essential equipment for its economy and security-industrial complex under the radar of Western oversight. These transfers rely on the strategic deployment of front and shell companies around the world. Analysis of these front and shell companies, which facilitate the transfer of aircraft to Iran, indicates that the IRGC typically establishes them in countries with limited commercial transparency, including Gambia, Madagascar, Kenya, South Africa, Namibia, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Ukraine.

After the front or shell company completes the purchase, the next stage is transferring the aircraft to Iran without raising suspicion. This step involves significant risk, as detection of the transfer plan by authorities in the originating country can thwart the operation. For example, in 2024, when Iran attempted to smuggle three aircraft owned by Macka Invest Company, registered in Gambia, on flights originating in Lithuania, the third aircraft was stopped after authorities noticed that the first two aircraft had landed in Iran rather than the Philippines, the declared destination on the flight plan. To minimize the window of opportunity for authorities to intervene, smugglers almost always conduct the transfers in close succession. This operational approach is known in the field of fraud as “Burst Activity”: a series of rapid transfers designed to prevent law-enforcement agencies from identifying the illicit activity in real time.

To carry out the transfer, the front or shell company must file a legitimate flight plan with aviation authorities. However, the planned flight path is deliberately designed to pass close to—or even through—Iranian airspace. In this way, the aircraft can enter Iranian airspace, report a fabricated critical malfunction, and declare an emergency landing at an Iranian airport while switching off its radar system. The aircraft then “disappears” and is absorbed into the fleet of Iranian airlines. This method has been used repeatedly by the Quds Force, including in the three aircraft transferred from Lithuania; five aircraft smuggled via a Madagascar-based company in 2025; four aircraft transferred from South Africa under the cover of a flight to Uzbekistan in 2022; and many other cases detailed in Appendix A.

Another dimension is the deliberate political involvement of states that help circumvent the US sanctions. Iran’s ability to evade sanctions relies on the cooperation of foreign governments that allow Iranian entities to exploit their territory for the illegal purchase and transfer of aircraft and spare parts. This activity occurs in two main geographic areas. First, in Southeast Asia, Indonesia and Malaysia provide a largely permissive environment. Indonesia serves as a central logistical and transit hub, and its government’s lack of willingness to intervene enables local intermediaries to handle forged paperwork and the final smuggling of Western aircraft into Iran. Beyond aircraft smuggling, new research indicates that Iran also uses these states to bypass sanctions on its oil industry. Data shows a sharp rise in oil imports to China from Indonesia and Malaysia, masking the Iranian origin of the shipments. In some cases, the volume of oil imported from these states exceeds their own total production, reinforcing the assumption that the oil in question is in fact Iranian rather than Indonesian or Malaysian. Second, Central Asian countries and states aligned with Russia, including Mongolia, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, permit open trade with Iran, sometimes even through state-owned companies. Examples include Tajik Air, owned by the government of Tajikistan, and MIAT Mongolian Airlines, owned by the government of Mongolia.

The Structure of the Front and Shell-Company Networks and Analysis of Ownership

Beyond the general typologies of aircraft smuggling, it is essential to examine the individuals and financial structures behind these networks. As many of these companies open and close frequently, a deeper understanding of the underlying network that enables their activity is required. This involves examining the multi-layered ownership structures of front and shell companies in various countries, identifying the individuals who control them, and investigating their related activities.

One example is Avro Global Limited, registered in Hong Kong and owned by British citizen Gary Neil Webster. In 2019 the company purchased four aircraft from Turkish Airlines. The aircraft were stored in South Africa without activity until 2022, after which they were re-registered under an anonymous company in Burkina Faso and departed on a flight ostensibly destined for Uzbekistan. As already noted, the aircraft conducted a planned emergency landing in Iran and were absorbed into the Mahan Air fleet. In this case, aircraft smuggling is not Webster’s only activity on behalf of the Iranian regime. In fact, he is a long-standing business partner of brothers Nader and Yaser Al-Aqili, with whom he owns several companies. The Al-Aqili family has a long history of smuggling and financing networks on behalf of Iran, and several family members and affiliated companies have already been placed on US sanctions lists. For example, ACS Trading, jointly owned by Webster and Yaser Al-Aqili, is believed to have functioned as an Iranian front company that facilitated gold transfers from Venezuela in exchange for Iranian oil. The company has also cooperated extensively with Mahan Air, which further reinforces the relationship between Webster and the Iranian entities and explains his role in facilitating aircraft smuggling through his company registered in Hong Kong.

Asia Sky Lines from Tajikistan presents a different pattern of activity. In 2019, it transferred three Airbus aircraft to Iran, but unlike other companies that cease operations after the transfer, this company continued and transferred two additional aircraft in 2020, one in 2021, and another in 2023. A closer examination reveals that the company is owned by Narzikul Khamraev. Beyond its direct connection to Iranian airlines, the company was previously linked to aircraft that supported the Wagner Group in Africa. In addition, Khamraev served as the CEO of another airline, Asia Airways, which was registered at the same address as Asia Sky Lines but had different ownership.

Another example is the French company LMO Aero, which purchased two Airbus 340 aircraft from the French Air Force in 2021. After about two years, LMO Aero sold the aircraft to a front company associated with the Iranian airline Mahan Air. The aircraft were transferred to the ownership of an anonymous company in Mali; about two months later, one aircraft arrived in Iran and the second reached Conviasa, which is Venezuela’s state-owned airline. Behind LMO Aero is Ludovic Martinho, indicating involvement of European actors in the smuggling network.

Lastly, we can also examine Udaan Aviation, a company registered in Madagascar, which is owned by businessman Khushwinder Singh and his partner Rahul Chawala. The two also jointly control several other ventures, including companies in the mining and cryptocurrency sectors. In July 2025, Udaan Aviation transferred five aircraft to Mahan Air through a complex routing scheme that moved the planes from Indonesia, via Cambodia and Madagascar, before their final delivery to Iran.

Summary and Conclusions

The Iranian method for circumventing sanctions on the aviation industry relies on three consistent components: (1) the use of shell and front companies located in states with limited regulatory transparency; (2) multi-layered ownership structures designed to obscure the direct connection to Iran; and (3) the use of “burst activity”— a rapid sequence of transfers intended to exploit the narrow window between reporting and detection. This system reflects an institutional mechanism built on the regime’s long-standing experience in smuggling oil, gold, technology, and spare parts.

It is also important to distinguish between states operating under cover and those acting openly. Countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Kenya allow their territory to serve as an operational space, turning a regulatory blind eye without direct involvement. In contrast, other states, primarily Russia and China, deviate from this covert model and facilitate Iranian activity openly, at times through state-owned entities. In doing so, they effectively help neutralize the impact of Western sanctions and strengthen Iran’s ability to maintain the logistical infrastructure of its aviation industry.

The smuggling operations themselves illustrate the combination of a shadow-economy infrastructure with strategic-security objectives. Companies such as Mahan Air and Qeshm Fars Air serve as logistical arms of the Quds Force, while front and shell companies in Africa, Asia, and Europe provide an ostensibly civilian support channel. This enables Iran to maintain a dual-layered smuggling system: outwardly civilian, internally military.

It is unlikely that the activation of the snapback mechanism will fundamentally change this reality. The American threat of secondary sanctions has already produced strong deterrence among airlines, manufacturers, and financial intermediaries, limiting Iran’s ability to conduct open transactions in aviation or in international trade regardless of the renewed application of sanctions under the UN Security Council framework.

Finally, Iran’s long-standing pattern of activity demonstrates a high degree of adaptability and consistent exploitation of regulatory gray zones—factors that will make it difficult for Western states to enforce sanctions even if they are intensified and regulations tightened. As long as no unified international framework is established that includes states outside the Western consensus, Iran will continue to operate “under the radar,” combining commercial networks, security proxies, and protective states.