Strategic Assessment

Taiwan, and the complex, tense relations that surround it, is considered a significant “hot spot” in the global arena. The more the competition between the two major superpowers, the United States and China, escalates in the Asian or Indo-Pacific arenas, the more the tension surrounding the issue of Taiwan intensifies, the rhetoric grows extreme, and the actions of the two sides form a new status quo that threatens to be replaced overnight by real warfare. To understand the events surrounding the Strait of Taiwan, this article examines the reasons for the strategic importance of the controversial island; reviews Taiwan’s historical background as reflected in US-China relations; and highlights the “third Formosa crisis” (1995-1996). In doing so, it maps the primary trends and prominent changes that occurred in the dispute over the island until 2016, which marks the beginning of a new era in these relations.

Keywords: China, Taiwan, United States, Formosa Crisis, Communist Party, Gaomindang, DPP.

Introduction

In recent years, and especially since 2022, the media has been full of reports pondering whether the People’s Republic of China is heading for war with Taiwan to achieve the island’s forceful unification with the mainland. The media storm intensified against the analogy of Taiwan to Ukraine, which was invaded by Russia in February 2022; the visit of Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the US House of Representatives, to the island in August 2022; the Chinese military response to this visit, during and following it, and in May 2024, upon the swearing-in of a new president in Taiwan. Still, the media and academic storms have typically addressed the events of the hour in an overly specific manner, while assigning secondary, if any, importance to the historical background and long-term trends in China-Taiwan relations.

Also missing from the discussions is any comparison with other crises in this context, particularly that of 1995-1996. The present article, therefore, will review the strategic importance of Taiwan in general; examine China-Taiwan relations, through a historical lens including the various crises and US-China relations, which have had decisive influence on the issue; map the major trends in this tripartite relationship until 2016, with the coming into office of the DPP (the Democratic Progressive Party, which recently began its third term in the Presidency of Taiwan), when relations took a turn that requires separate examination in its own right. The main question underlying this article is: How have the dynamic relations between China, Taiwan, and the United States, in addition to the changing interests of all three, influenced Taiwan’s positioning in the regional (East Asian) and in the global space and its own self-understanding?

The Strategic Importance of Taiwan

Taiwan consists of several islands (some located just a few kilometers from mainland China), of which Taiwan is the major one both in terms of land area and population (and whose name is therefore often used as a synonym for the Republic of China [ROC] in general. In what follows Taiwan will be used to refer to the singular island of Taiwan for the pre-1949 era and the entire collection of islands, also known as ROC, for the post-1949 period.). Today, Taiwan has 23 million inhabitants and an 800 billion dollar (gross domestic product) economy (in 2023)—that is the world’s twenty-first strongest, with a per capita average annual income of more than $30,000.[1] Still, most of the world does not formally recognize Taiwan as a sovereign independent state (except for a handful of countries, primarily in the Pacific Ocean and in South and Central America), and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) regards it as an integral part of China and a “district in rebellion” that must be unified with the Chinese “homeland.” Even within Taiwan itself this is a controversial issue, leading to disagreements from both sides of the Formosa Strait, which separates the island of Taiwan from the PRC.

The island of Taiwan was not ascribed any special strategic importance until the seventeenth century, when its strategic location, the rise in scope of international trade and the superpowers’ increasing presence in the region, gave it expanding significance. The main geostrategic reasons for this growing importance are as follows:

- The island’s relative proximity to the mainland (southeast of China—at a distance of 160 kilometers on average—provides access to trade areas and to the estuaries of important rivers in southeast China that lead inland (the importance of Taiwan’s location grew in the early modern period together with the expansion of trade).

- Taiwan’s location between northeast and southeast Asia, or between the South China Sea and the East China Sea, in close proximity to international trade routes (and maritime currents) running from southern China, Vietnam, the Philippines, and other countries in southeast Asia, to Japan and Korea, in the northeast.

- The region is also strategic from a military perspective (navy, air force, missiles, etc.), whether due to its access (or lack thereof) to the South China Sea, an area that in itself constitutes a sensitive issue in the region due to intensified Chinese activity in recent years, or to the access or lack thereof to the East China Sea, on the way to China, Japan, and Korea.

- Its location on the route linking western America to China via the Pacific Ocean—This maritime route first became significant in the early modern era, but its significance intensified from the second half of the nineteenth century.

- The island of Taiwan itself is located at a crossroads of maritime topographies: to its west, toward China, the ocean is relatively shallow (depth of 40-60 meters, and sometimes less); to its east, toward the Pacific Ocean, the depth of the waters plunges quickly to hundreds of meters and even deeper. This is the source of the island’s geostrategic importance in terms of resources (energy and fishing, for example), as well as its military and security importance (especially from the twentieth century onward, vis-à-vis submarine activity).

Map 1. China and Taiwan in broad context. | Design: Shai Librovsky

When we consider these factors together, we understand that the island has become not only a stopping point during maritime voyages, but also a kind of immense (and fertile) base at China’s doorstep. It comes as no surprise, then, that the island became a coveted target for control by the Japanese as they worked to expand their empire from the end of the nineteenth century; and by China, in order to protect the strategic space surrounding it to the east. Clearly, for the United States and its allies, Taiwan is a strategic asset for any action in the region and for securing routes of access to and from the region. The more the United States develops alliance systems in the Indo-Pacific region, especially under the Biden Administration, the more Taiwan constitutes a center connecting the alliance systems of northeast Asia (Japan and South Korea) with those of southeast Asia to Australia—even if not necessarily in an explicit or official manner. For China, therefore, US control over Taiwan is a break in “the first island chain”—a collection of key points facing the coast or borders of China—that it regards as an attempt to limit its actions in eastern Asia and beyond. In addition, in recent decades Taiwan has become a world leader in the production of microchips, explaining its essential role in the production and supply chains of an immense variety of products for the entire world, the PRC and the United States included. The fact that Taiwan possesses some of the world’s largest foreign currency and gold reserves also increases its economic importance (Chen, 2024).

For the PRC, however, more than all these concrete elements, Taiwan’s “return” to the bosom of China is perceived as a “core interest” (核心利益) that constitutes a red line regarding which there is no room for compromise or negotiation (Fang & Zhao, 2021). This stems not only from its economic, security, and geostrategic importance, but rather mainly because the division between Taiwan and the PRC is perceived as an “original sin” and lies at the heart of the national ethos of building the Chinese nation, or, according to the rhetoric of current Chinese president Xi Jinping, “the national rejuvenation of China.” Historically, moreover, and not in modern China alone, “separatism” (分裂) is typically perceived as one of the most serious “crimes” against the sovereign (see, for example: State Council, 1993), regardless of the identity of the “separatists”; as an unacceptable precedent; and as a relinquishment of an essential element of Chinese national culture. Because Taiwan’s very existence is defined as such “separatism,” any compromise on the issue is also viewed as untenable, as relinquishing an essential element of the national identity of the PRC, and as n undermining the fundamental reason for the very existence of the PRC—the Communist Party of China (CPC). Moreover, for the PRC, Taiwan is a mirror image— an alternative Chinese regime in which the absolute sovereign is not the Communist Party but rather the state and the liberal-democratic state regime. By its very existence, this alternative is perceived as a threat to the CPC regime.

Thus, despite the facts that on both sides of the Strait the Chinese language is dominant, ethnic belonging is largely similar, and, on many occasions, culture and religion are also very similar, the major question that has been hanging over the island for more than seven decades has been: What is the real China, and to which China does the island belong?

Historical Background

During the seventeenth century, with some inroads in the sixteenth century, the Portuguese (who apparently were those who coined the term “Formosa,” meaning “beautiful,” for which the Strait was named), the Spanish, and then the Dutch made their way into East Asia. They regarded Taiwan as an important anchor between northeast and southeast Asia—destinations which for them were particularly important. The Dutch also established a small port on the island to meet their needs in the region. Although the island had a small indigenous population, it had not, by that point in history, been forced to answer questions of sovereignty, and as an unimportant island it had also not been the site of any unusual battles. However, in the seventeenth century, the Chinese arena was turbulent, and the Manchus gradually succeeded in defeating the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), conquering the territory it had controlled, and establishing a new dynasty: the Qing Dynasty (1635-1911). During the conquest years, one loyalist of the previous (Ming) dynasty fled to Taiwan with an army, accompanied by a wave of immigrants who feared the Manchus, by means of the Ming Dynasty navy; they conquered the part of the island that was held by the Dutch and established a base of their own there, thus creating in Taiwan a small renegade regime to the Manchus in China. In this way, the island of Taiwan captured the attention of the Qing Dynasty shortly after it established its rule over the entire Chinese mainland. In the 1680s, the Qing Dynasty embarked upon a campaign of war against the “rebels” in Taiwan and subdued them. Taiwan became part of the sovereign territory of the Qing Dynasty (although rebellions on the island continued to trouble its rulers) for a period of approximately 200 years (Andrade, 2008).

However, at the end of the nineteenth century, a new power emerged in East Asia: Japan. It was the Ming era (1868-1912), and from the 1870s Japan began seeking to expand its territory and sovereignty into additional regions in eastern and northeastern Asia (Mizuno, 2009). In 1874, shortly after an incident in which Japanese sailors were killed on the shores of Taiwan, Japan successfully invaded the island but withdrew after being paid compensation by the Qing Dynasty. Approximately one decade later, during the Sino-French War (1884), France also attempted to invade the island, but without success. As a result of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, in which China suffered a stunning defeat, Taiwan in its entirety was seized by the Japanese and became part of the Japanese empire until the end of World War II. During this period, Japan introduced modernization and industrialization (on many occasions working against the local population of Taiwan), including a railway system, and turned Taiwan into an important base of operations in the Pacific region during World War II (Liao & Wang, 2006).

In the meantime, in China proper, the Qing Dynasty collapsed (at the end of 1911), and the Republic of China (ROC) was established, led by the figure known as the “father of the Chinese nation”: Dr. Sun Yat-Sen. The newly formed ROC was governed by the Guomindang (the nationalist party, transcribed in Taiwan as Kuo-min-tang, henceforth KMT), but in the first decade-and-a-half of its existence its control of China was weak and extremely partial. In 1921, the Communist Party of China (CPC) was established, and despite an element of cooperation between the two parties at the beginning of the 1920s, relations between them quickly became violent. In 1927 and 1928 (that is, during and after the unification of a large portion of the Chinese state) the KMT tried to eliminate the members of the Communist Party and to establish one party rule led by General Chiang Kai-shek (who rose to power after the death of Sun Yat-Sen in 1925). The Communists were forced to flee or to go underground; they managed to survive the persecution, and in doing so they began to build initial foundations for their own rule, particularly in remote rural areas, in parallel to the KMT’s military campaigns against them. The latter also resulted in the Communists’ Long March (1934-1936), in which they kept moving for thousands of kilometers, from southeast China, via the western regions, to the north. Despite the mutual animosity between the two sides, both parties were forced to resume an element of cooperation during World War II in order to resist Japan, which had begun a gradual invasion of mainland China in the 1930s (in East Asia, the war was at full intensity already in 1937).

From the 1920s until the 1940s, the CPC’s approach to Taiwan differed from the form it assumed after World War II. First, the CPC recognized the Taiwanese as an “ethnic group,” a “nationality” (民族), and even a “race” (種族) that was separate from that of the Han Chinese. The Taiwanese were referred to in the same breath as Koreans, Mongols, Muslims, and others. At the time, the CPC also supported the Taiwanese, who were fighting “Japanese imperialism” and explicitly sought to act against the Japanese together with other nations, including Korea and Taiwan, for example, on the way to a broad scale international communist revolution. The Taiwanese who helped the Japanese in mainland China, in Fujian for instance, were portrayed not as traitors against their homeland but rather as foreign agents. In 1941, Zhou Enlai, deputy chairman of the CPC who was responsible for foreign policy for many years, declared unequivocally that the Chinese needed to act together,

…with the liberation and independence movements of other nation states. Not only will we assist the anti-Japanese movements of Korea or Taiwan, or movements against German or Italian aggression, of nations in the Balkans or in Africa, but we are also working together with national liberation movements in India and in a variety of states in Southeast Asia.

His words portrayed Taiwan as one of many other nation states that were not China (Hsiao & Sullivan, 1979, p. 453).

Concurrently, the KMT was somewhat more resolute regarding Taiwan’s belonging to China and claimed distinctly that Taiwan (and Korea, incidentally) was originally part of China. Nonetheless, the KMT maintained an element of ambiguity and appears to have implicitly accepted the idea that Taiwan—paralleled to Korea—could be independent or enjoy an element of independence, and in any event held that both (Taiwan and Korea) should receive help in liberating themselves from the Japanese. The turning point in the approach of both parties, the KMT and the CPC alike, to the issue of Taiwan, occurred around the Cairo Conference in November 1943, where Roosevelt, Churchill, and Chiang Kai-shek formulated concrete principles for the postwar world order. In the Cairo Declaration, these leaders agreed that Taiwan was part of China and should be returned to China. Both parties accepted this principle, and from this point on the policy of both parties was unequivocal: Taiwan was and was meant to be an integral part of China (Hsiao & Sullivan, 1979).

The end of the World War also marked the end of cooperation, as partial as it was, between the KMT and the CPC. Despite American efforts to bring KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong, leader of the Communist Party from the mid-1930s onward, to negotiations towards a continued shared existence, a bloody civil war quickly broke out in China. This war, which erupted in parallel to the beginning of the Cold War and the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union, prompted the Chinese parties to align with one of the sides in the Cold War: the KMT with the United States, and the CPC with the Soviet Union. After several years of civil war, the army of the CPC succeeded in driving the army of the KMT out of mainland China. In this way, Chiang Kai-shek found himself with what remained of his army and one and a half million refugees from China on the island of Taiwan, from which the Japanese withdrew at the end of 1945. On October 1, 1949 Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, leaving the ROC and the PRC facing one another from either side of the Strait of Formosa—each with the respective superpower supporting it, and each claiming to be the true and authentic representative of greater China.

Over the years, beginning in the 1910s, the ROC (and later Taiwan) was regarded by most of the world as the official representative of “China.” Thus, during World War II, it was Chiang Kai-shek who met with leaders such as Roosevelt and Churchill, and when the United Nations was founded, it was the ROC that became one of the founding states and a permanent member of the UN Security Council. When the ROC and the PRC separated in 1949, the ROC (Taiwan) continued to serve as the China representative to the UN, and many states did not even recognize the PRC, nor maintain diplomatic relations with it.

The People’s Republic of China-Taiwan-US Triangle, 1949-1995

The stormy 1950s in Asia, and most importantly the Korean War (1950-1953), caused the United States to assign increasing importance to every country in Asia, no matter how small (the Truman Doctrine) (Yoshihara, 2012). Beginning in the 1940s, the PRC saw the Asian space surrounding it (and not East Asia alone) as part of the “intermediate zone” (一个中间地带)—a concept developed by Mao during the decade following World War II, based on the idea that in the struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union, the United States was trying to seize control of various countries in the world, and only then to engage in conflict directly with the Soviet Union. East Asia, as a mirror image of the US Domino Theory threat, was perceived as a necessary stage on the road to total American world domination. From China’s perspective, then, the struggle against the American attempt to achieve hegemony in the intermediate zone was critical to the global future, and Taiwan, like other states in the same region, was an Archimedean point for this struggle, particularly as a possible point of American entry into China itself.

It was in this context that China unsuccessfully attempted, in October 1949, to conquer the island of Kin-men, just kilometers away from China’s eastern coast, and staged a successful conquest (or “liberation,” to use CPC terminology) of the large island of Hainan, located southeast of China (An, 2013; Zhang, 1992). It is important to emphasize that during the preparations for the military campaign to conquer Hainan, Mao explicitly instructed the commander of the army, Lin Biao, that “the principle of the attack on the island of Hainan should be that we must be completely ready and absolutely certain of victory before we start the attack; and that we must completely refrain from any haste or irresponsibility” (以充分准备确有把握而后动作为原则,避免仓促莽撞造成过失) (Yang & He, 2020). This principle, and the civic influence campaign in Hainan, which preceded the successful attack of the spring of 1950 (Murray, 2017), continues to reverberate in today’s PRC, while the memory of the loss of Hainan is also present in Taiwan.

Map 2. The Formosa Strait. | Design: Shai Librovsky

The PRC threats against Taiwan, which were accompanied by actual warfare on two occasions (the “first Formosa crisis,” in 1954-1955, and the “second Formosa crisis,” in 1958), were also part of the PRC’s strategy to handle the United States in the region, vis-à-vis the Korean War and American actions in Vietnam. These threats appear to have been more of an attempt to influence the mood in Taiwan (similar to the attempts in Hainan, in preparation for the concrete military action) than the beginning of a full scale military campaign against Taiwan. Nonetheless, in January 1955, China’s threatening moves caused the United States to legislate the “Formosa decision,” which authorized the president of the United States to use force to defend Taiwan (Mutual Defense Treaty, 1954). At the same time, the idea of a “median line” (or the “Davis line,” after the American general who proposed it) also entered the informal lexicon: an imaginary line, running more or less down the middle of the Strait, that separated Taiwan from the mainland and that the military forces of China and Taiwan were not supposed to cross. Though never formalized in an official agreement of any kind, this line remained in place for decades, with virtually no crossings from either side (until recent years). The warfare in both crises occurred primarily on and around small islands located very close to the mainland (a distance of up to 10 kilometers), and except for several air or sea battles (in the second crisis), most of the fighting consisted of mutual artillery bombardment, despite the use of nuclear threats on the part of the United States (Trent, 2020).

During this period, between 1954 and 1959, the statements made by CPC leaders such as Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong defined the party’s distinct attitude to the Taiwan issue from that point on (Chen, 2019):

1.The Taiwan issue is an internal issue (内政问题) that holds no relevance for any other state, whereas every discussion with the United States (or any other country) is an international issue (国际问题), which are two completely different matters. This is a critical distinction from the perspective of the CPC.

- “Taiwan is ours, and under no circumstances should concessions on this matter be made” (台湾是我们的,那是无论如何不能让步的).

- The Taiwan issue is the result of foreign imperialism (帝国主义) (first Japanese, then American).

- The issue can be resolved by “liberating Taiwan through peaceful measures” (和平解放台湾), but if this fails, there is nothing to prevent the use of military force to achieve the aim of “liberating Taiwan.”

Throughout the 1950s, the feeling in the PRC that “peaceful measures” were no longer an option grew. However, due to PRC’s weakness at that time, the violent clashes faded for the most part by the end of the decade, although the aggressive ideology remained. On the other hand, the propaganda clashes between the PRC and the ROC continued, with each trying to convince the citizens of the other country that it was the one and only real China, while the other was the embodiment of evil (Aldrich et al., 2000). At the same time, in the 1950s, both with the support of American aid and as a result of wise economic policy, Taiwan began maneuvering out of destruction and poverty and towards economic growth: first, as a result of a process that allowed farmers greater economic freedom; and gradually, into the 1960s, as a result of a process of rapid industrialization that transformed the island into a significant export economy. Taiwan’s alliance with the United States and its allies in East Asia (primarily Japan, and South Korea) contributed significantly to this success and to Taiwan’s solid economic position, which only accelerated in the decades that followed (Kuo, 1983).

In parallel, beginning in the 1950s, and with greater intensity in the 1960s and 1970s, relations between the PRC and the Soviet Union worsened, to the point of a border clash in 1969. On the other hand, beginning around 1970, ties between the PRC and the United States began to take form. It is important to remember that in the 1960s, other Western countries such as France (1964), had established diplomatic relations with the PRC, so that at the beginning of the 1970s, the PRC was no longer as isolated as it had been in its early days. The outcome of the warming of relations between it and the United States and other countries in the West, was that at the end of 1971, the UN passed a resolution that the ROC no longer represented “China,” and that the PRC would now represent China at the United Nations in its stead. The United States, interestingly, abstained in this vote. Still, relations between the United States and Taiwan remained positive (Nam, 2020).

In 1979, relations between the PRC and the United States matured into full formal diplomatic relations. Taiwan paid the diplomatic price, again, when the United States ceased to recognize it as a state for all intents and purposes (the embassy and the consulates of Taiwan in the United States were no longer referred to as such and became economic, commercial, or cultural offices). Nonetheless, the United States sought to strengthen its commitment to the security of Taiwan and to maintain its relations with it. The result was the Taiwan Relations Act of the same year. This law maintained relations between the United States and Taiwan from an economic and a security perspective, alongside the diplomatic downgrade towards non-recognition of Taiwan as a sovereign state that was separate from the PRC (Goldstein & Schriver, 2001). Immediately thereafter, the United States continued with another series of binding statements (known as the Six Assurances and the Three Joint Communiques), which explicitly normalized its commitment to the “One China” policy, on the one hand, and its commitment in practice to Taiwan, on the other hand (Kan, 2009).[2]

The “One China” principle requires some explanation, as the different players interpret it differently (Drun, 2017). This issue took center stage during President Nixon’s visit to China in 1972 and in the Shanghai Joint Communique from the same visit (Joint Statement, 1972). In this communique, China advanced the principle of One China from its perspective, and the United States presented its own One China policy. The Chinese principle, according to the communique, was that “the Government of the People’s Republic of China is the sole legal government of China” and that “Taiwan is a province of China.” In contrast, in the same document the United States stated that “all Chinese on both sides of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China.” It appeared that both had accepted the position that there was only one country named China that faithfully represented “China,” and that it was not possible to separate, divide, or split-off different countries claiming to be China. However, as noted, Taiwan regarded itself as the One China for many years, while the PRC also maintained that it was the One China. American statements, in the Joint Communique of 1972 and subsequently, did not determine which was the true One China, and in any event the path to creating that One China would be one of peace and dialogue. The PRC agreed to this, to the extent that this was possible. Indeed, the PRC itself ostensibly proposed “peaceful measures” back in the early 1950s; however, the context in which the UN accepted the PRC as the representative of China in 1971, and the fact that in 1979 the United States sought formal relations with PRC at the expense of Taiwan, resulted in a prevalent feeling that beside the formal vagueness regarding the question of One China, the United States was relating to the PRC as the “One.” Still, the United States also insisted (and continues to insist) that using the term “policy,” as opposed to the term “principle,” allows for greater flexibility in understanding the idea in question and allows for change to this policy (Goldstein, 2023).

The broader context of the US desire for closer relations with the PRC in the 1970s and the early 1980s also included the Cold War and the desire to include the PRC among the countries that were opposed to the Soviet Union; the fear during the years in question of the increasing economic strength of Japan; and the naïve assumption, which may have stemmed from ignorance or possibly over-optimism, that the closer the PRC got to the United States and the “enlightened” West, the more China itself would “see the light” and seek a liberal democracy for itself, as was customary in the West. As we will see below, the latter point would be put to the test a decade after the establishment of full relations.

From an economic perspective, in the second half of the 1970s and with greater intensity in the 1980s, Taiwan began to place an emphasis on its hi-tech economy, and especially on the manufacturing of microchips by different companies, led by TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company). As a result of this emphasis, Taiwan’s economy experienced particularly impressive growth throughout most of the 1980s and the 1990s, with success that was referred to as the “Taiwanese miracle.” At the beginning of the 2000s, Taiwan’s microchip industry was referred to as a “silicon shield” (Adisson, 2000, 2001). The silicon shield concept conveys the following ideas: Taiwan’s global importance with regard to microchips means, firstly, that the world became dependent on these microchips and would therefore defend Taiwan; and secondly, that China itself—which also needs microchips from Taiwan—would refrain from taking military action against the island so as to avoid damaging this industry, and especially its supply chain to China proper.

The increasingly close relations between the PRC and the United States in the 1980s allowed Taiwan and the PRC, in the second half of the decade, to begin to establish informal relations with one another, based on visits, economic links, and, gradually and secretly, diplomatic conversations and an attempt to reach understandings (Tung, 2005). At the beginning of the 1990s, according to various reports, this attempt developed into what was referred to in retrospect as “1992 consensus.” Within this framework, the PRC and Taiwan agreed to the One China principle, but also agreed that this principle would be implemented gradually via dialogue and over time, and without explicitly stating which country was the true One China.

This consensus, to the extent that it existed (there are contradictory statements on this point), was reached when the PRC was in need of greater international legitimacy, particularly Western legitimacy (Wang et al., 2021). As a result of the Tiananmen Square incident of 1989, large parts of the Western world came to regard the PRC as a problem. The violent suppression of the massive protests, which sought democratization, caused the Western world to rethink its relations with the PRC, as well as to rethink the probability of the assumption regarding China’s track to liberal democracy (Foot, 2000). The Gulf War (1991) demonstrated to PRC how far it still was from modernization (especially in the technological and military realms), as opposed to the United States, and Taiwan’s technological abilities were therefore alluring. In addition, although the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union allowed the PRC to renew its relations with Russia, which was not troubled by the events of Tiananmen Square, the technological and economic gap between Russia at the beginning of the 1990s and prosperous Taiwan or other Western countries was significant.

When President Clinton entered the White House at the beginning of 1993, it appeared that, as an extension of his campaign promises, Washington would take a more stringent approach to China and would more closely connect the subject of human rights in China to the issue of trade. However, less than two years later, the Clinton Administration severed this first connection between human rights and trade, supposedly in order to help bolster relations between the countries (Baum, 2001; Shambaugh, 2000). On the other hand, at the end of President Bush’s term in office in 1992, a decision was made to provide Taiwan with 150 F-16 fighter jets. In addition to previous declarations and decisions of the United States, in which it expressed its obligation to defend the island, the PRC was extremely displeased with the direction in which it appeared that Taiwan was heading. American protection and advanced weaponry were perceived as means that would enable Taiwan to avoid implementing the terms of the 1992 consensus, and especially to withdraw from the agreement (as the PRC saw it) that the PRC was the One China (Lee, 1993).

In the meantime, in September 1993, China published a first “white paper” on the subject of “the Taiwan question and the unification of China” (台湾问题与中国统一) (State Council, 1993). In this document, China asserted that “the solution to the Taiwan question and the realization of the unification of China are the weightiest and most sacred task of the entire Chinese People” (解决台湾问题,实现国家统一,是全体中国人民一项庄严而神圣的使命). China emphasized that its fundamental policy regarding the resolution of this issue was “unification through peaceful measures and one country—two systems” (和平统一、一国两制), the approach that appears in the agreement with Britain regarding Hong Kong. The white paper unequivocally clarified that “the world has only one China; Taiwan is an inseparable part of China” (世界上只有一个中国,台湾是中国不可分割的一部分), and that for more than a decade prior to the publication of the document, the Chinese leadership had espoused these principles of “One China,” “unity through peaceful measures,” and “one state—two systems.” In the same document, in a manner that has persisted consistently until today, China also presented the Cairo Declaration (1943) as a binding international document that defines Taiwan as part of China (although the Chinese representative to this conference was of course Chiang Kai-shek).

The Third Formosa Crisis and Its Aftermath

When the PRC published the first white paper on the issue of Taiwan in 1993, Taiwan itself was deep in the midst of a process of democratization. After decades of dictatorship led by Chiang Kai-shek, and since the mid-1970s under the rule of his son Chiang Ching-kuo, Taiwan began to undergo a gradual dramatic shift. Initially, after free elections (which were later split into parliamentary elections and presidential elections), the government remained in the hands of the KMT party (the party that had been led by Chiang and his son), but voices that did not accept the principle of One China gradually began to emerge and gain momentum. Lee Teng-hui, who was appointed president after the death of Chiang Ching-kuo in 1988, was the one who led the democratization process that developed into the first elections for the presidency in 1996. Leading up to these elections, Lee, a member of the KMT, emphasized Taiwanese identity, sought to limit ties with the PRC, and to strengthen connections with the United States (Jacobs, 2012).

Accordingly, Lee sought to visit the United States. Whereas in 1994 Washington had refused him a visa, under Chinese pressure, in mid-1995 he was granted one. Despite the opposition of the US administration, both houses of Congress (then under Republican control) passed a decision that demanded that the administration allow Lee to visit the United States. The decision passed with a crushing majority of 397:0 in the House of Representatives and 97:1 in the Senate. Even if the American administration did not think that such a step was wise, at this point it surrendered to pressure, and Lee Teng-hui paid what was portrayed as a private visit to Cornell University (where he studied in the 1960s) in June, 1995. Beijing’s resolute reaction was quick to come and propelled the “third Formosa crisis” into high gear.

It is important to note that only a few months earlier, on January 30, 1995, in a major speech on the issue of Taiwan, Chinese President Jiang Zemin had presented a plan of “compromise,” as the PRC viewed it, for reconciliation with Taiwan through peaceful measures. This plan recognized Taiwanese democratization and did not insist on the idea of “one country, two systems” as a basis for negotiations, which, as noted, was the idea that facilitated the agreement with Britain regarding the return of Hong Kong to the PRC. Taiwan’s lukewarm response to this proposal disappointed Beijing and resulted in a feeling of humiliation. Still, the talks between the sides continued, along with growing resentment on the western side of the Strait. The United States had let the PRC understand that Lee Teng-hui would not receive a visa, but it quickly became clear that he actually would receive one. The United States continued to support arms sales to Taiwan. And the Taiwanese president and his close associates sought to circumscribe relations with the mainland and to demand that the PRC publicly denounce any unity by force, while trying to advance Taiwan’s formal status among nations of the world (for example, through an attempt to acquire a seat in the UN) (Ross, 2000).

In Beijing, it seemed the discussions, either with the Unite States or with Taiwan, were pointless. From China’s perspective, American policy vis-à-vis Taiwan, especially after the end of the Cold War and the flourishing of the Chinese economy, boiled down to four characters: “Controlling China by means of Taiwan” (以台制华). These four characters were based on a concept that depicted China’s “century of humiliation” (from the mid-nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century): “Controlling China by means of the Chinese” (以华制华). The concept related especially, but not exclusively, to Japan, which from the Chinese perspective had made use of the Chinese in Manchuria or the coastal regions (for example, Wang Jingwei) to establish its control over China. Use of the term to refer to the US policy, replacing the Chinese with the Taiwanese, gives expression to Beijing’s deep resentment and sense of humiliation, as well as the feeling that the entire Taiwan issue, from the American perspective, was a colonialist legacy and an attempt to contain and belittle China. Since the 1990s (especially in recent years), the use of this term has also been prevalent in administration documents and in the Chinese media (Fan, 1997).

The immediate concrete response to Lee’s receipt of a visa in May 1995 was formal protest by members of the Chinese foreign service in the United States, in addition to the recalling of diplomatic delegations and the cancelling of high-level talks. The testing of a DF-31 intercontinental ballistic missile was conducted at the end of May, although it is difficult to determine whether this test had been planned ahead of time. In any event, the connection between these events was only natural. When Lee’s visit to Cornell occurred on June 9-10, 1995, the media in China went wild, publishing numerous articles that, in addition to emphasizing that Taiwan was an integral part of the PRC, referred to Lee himself as a “traitor.” The Chinese ambassador to the United State was recalled back to his country, and the PRC announced that toward the end of July it would begin various military exercises, including live-fire exercises (“missile tests”) in the East China Sea region—in other words, in Taiwan’s direction.

And indeed, this is what transpired. For approximately a week at the end of July and ten days at the end of August, China conducted wide-ranging exercises, including live fire from planes, ships and artillery, and landing exercises on various islands. Short range (DF-15) and medium range (DF-21) ballistic missiles—some of China’s most advanced missiles at the time—were fired toward Taiwan in addition to various kinds of rockets. In mid-August, China also conducted a nuclear test, apparently of a warhead for a DF-31 missile. The PRC may have hoped that as the elections in Taiwan approached, the unequivocal message it had tried to send—that the One China principle must be maintained—had been conveyed. This message had several target audiences: the party of Lee Teng-hui, the KMT, which may decide to replace him; Lee Teng-hui himself and his associates; those in Taiwan who were calling for final separation between the Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China (the “independence” of Taiwan supporters); and those who were perceived as weakening the One China principle.

Between the two exercises, the foreign minister of China and the secretary of state of the United States met on the sidelines of the ASEAN conference, but their meeting bore no real results, except for a declaration that they would continue to engage in dialogue. The United States continued to state, in a weak voice, that its policy regarding Taiwan and One China had not changed, but nothing more. Still, China decided to return its ambassador to Washington, and it appeared that the crisis had subsided. Between September and November, the Chinese foreign minister and the US Secretary of State met repeatedly, and a brief summit between their presidents took place. The Chinese military continued to conduct exercises, but with no direct proximity to Taiwan, which was perceived as less of a threat to the island, even if the scale of the exercises was larger. However, at the beginning of December, one day before the parliamentary elections in Taiwan, China announced that it would conduct larger scale, more comprehensive exercises in March, just before the presidential election in Taiwan.

In addition to the announcement apparently resulting in sharp drops on Taiwan’s stock exchange, it may also have been one of the factors that resulted in election results that were less positive for Lee Teng-hui, and was certainly perceived as such by Beijing at the time. Although his party remained the largest in the legislature (with 85 seats), it lost 17 seats. The New Party (which split from the KMT a few years earlier and supported union with the PRC), on the other hand, achieved unprecedented success, winning 21 seats (in the previous elections, it ran under a slightly different name and won only seven seats), and the DPP also gained three seats (for 54 in total). From the perspective of the PRC, the pressure had worked.

On December 12, 1995, a battle group led by the American aircraft carrier the USS Nimitz passed through the Strait of Taiwan, on its way to the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf. Whereas this step is sometimes understood as a message from Washington to Beijing, it was part of a planned deployment and a passage that was apparently caused by considerations pertaining to weather and navigation, not by an attempt to convey a geostrategic message. Beijing also appears to have dismissed this act as lacking any meaningful signal of any kind. In China, the fact that the United States continued to grant visas to senior Taiwanese officials during January 1996 only reinforced the feeling that there was no one to talk to in Washington.

And so, assuming a deaf ear in Washington, China amassed large forces in the Nanjing command (the command responsible for the Taiwanese front): some 150,000 soldiers, hundreds of airplanes and helicopters, ships, air defense components, and missiles. The United States warned China against “erroneous calculations” or “mistakes,” and sought to restore order. However, Beijing continued to engage in additional military exercises during March, which only intensified in scope and in proximity to Taiwan. At the same time, the Chinese military continued to launch missiles (DF-15) and also made use of a civilian maritime force, an act that would repeat itself over the years. At the same time, the United States dispatched a battle group led by the aircraft carrier the USS Independence—which was usually stationed in Japan, not far from the area in any event—to closely follow the events along the coast of Taiwan. Shortly after, it also sent the battle group led by the USS Nimitz, which was in the Persian Gulf at the time. Both battle groups remained a safe distance from the exercises themselves and did not get directly involved, because Washington was convinced that China, in any event, would not attempt to invade Taiwan. These events occurred concurrently with the presidential elections in Taiwan and, contrary to expectations in Beijing following the parliamentary elections in December, the Chinese actions did not result in the fall of Lee Teng-hui, who won the presidency with a 54% majority of the votes. The new/old president did not declare independence, the Chinese pulled back their forces, and the major crisis came to an end, at least temporarily.

During the months of the crisis, from May 1995 to March 1996, whereas the PRC maneuvered militarily vis-à-vis Taiwan, its actions were in fact directed, perhaps primarily, at Washington, demonstrating its desire to preserve the status quo between United States, the PRC and Taiwan according to the agreements that had been reached since the 1970s. That is, a status quo in which all are committed, not only in rhetoric but rather also in practice, to the One China principle according to the Chinese understanding thereof. However, it is doubtful that Beijing’s goals were achieved.

In 1997 Newt Gingrich, then Speaker of the US House of Representatives for the Republican party, visited Taiwan. Gingrich was the highest-ranking American official to visit Taiwan in decades. However, this visit occurred after the elections had already been decided in Taiwan, and after the PRC was deterred by the American forces in the region or did not intend to continue beyond the exercises in any event. It is also important to remember that, in addition to the fact that part of the American conduct was related to internal political considerations, such (internal) motivations also played a role for the PRC: in 1995, reports that Deng Xiaoping had a serious medical condition began to flood the Chinese media. Jiang Zemin, who until that point had been in Deng’s shadow, needed to assume the reins of government in a clear and resolute manner. Once his conciliatory suggestions regarding the issue of Taiwan (from the end of January, 1995) received a cold shoulder, and Lee’s visit to the United States came to pass, he himself needed to show, domestically, that he was in fact the strong leader that was worthy of replacing Deng. (Thies & Braton 2004; Ross, 2000).

Later, the strengthening of Jiang’s standing also allowed him to return to the pragmatic position that had preceded the crisis in China’s foreign relations, referred to as the Good Neighbor policy (or diplomacy), or China’s “peaceful development.” Although this policy had begun a bit earlier (in the context of other countries in the region), the aftermath of the crisis of 1995-1996 accelerated the policy and the Chinese president at the time, Jiang Zemin, reiterated it several times at the most important Party conferences in 1997. It appears that the understanding in the PRC was that at that point in time, a positive policy toward its neighbors would yield more than a negative one. China experienced an economic boom in the 1990s, but progress had not yet been made militarily on a similar scale, and patience was necessary. In other words, the PRC knew that, militarily, it was at a disadvantage, but that economically—given the right diplomatic system—it could continue to grow stronger and thereby also strengthen its army with an eye toward the future. One of the lessons learned from the crisis was that the Chinese military required significant strengthening, particularly its A2/AD (anti-access/area-denial) capabilities. This was a lesson that was first learned during the 1991 Gulf War, and it gained notable momentum.

China proceeded accordingly. In the East Asian economic crisis of 1997-1998, the PRC was an important factor that helped stabilize the situation by providing economic and diplomatic aid to countries in the region. Its regional and international standing increased. Concurrent with its economic and diplomatic development, 1997 was also a year of fundamental change in terms of Chinese military development. From that year on, PRC’s military budget grew consistently by more than 10% in real terms (most of the time by more than 15% annually). In 1997, it was decided to separate the commercial activities of the army (which had engaged in many such activities over the years up to that point) and to place them in civilian hands, so that the army could focus on its military tasks. In addition, reform to the Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOE) facilitated the upgrading and reform of the Chinese defense industry. Also, the army transitioned from an approach of high-intensity warfare to one of local wars under modern, hi-tech, conditions. As a result, the Chinese army has developed impressively since then, from its technological abilities to its weaponry, to the type of training exercises employed in the different corps (Kanwal, 2007; Watkins, 1999).

Developing Relations in a Global Context, 2000-2016

In the United States, as the tension surrounding Taiwan in the 1990s did not interrupt US economic ties with the PRC, many understood that the PRC was quickly becoming a globally dominant country economically (and gradually militarily as well). Its dominance was not to be confined to “its own neighborhood” but also on the global level. If President Clinton referred to China as a “strategic partner” in the second half of the decade, the 2000 candidate for president, George W. Bush, was already referring to China as a “strategic competitor” of the United States. Central to the elections of that year was the question of using “a firm hand” or “too weak a hand” toward the PRC, in a preview of the years to come. However, despite the statements made by presidential candidate George W. Bush regarding the firm hand that was needed vis-à-vis China and the intense competition it posed to the United States, President Bush soon found himself in a different position (Shambaugh, 2000). First, a few months after the start of his term, on April 1, 2001, a collision between an American intelligence-plane and a Chinese fighter plane (apparently as a result of overenthusiasm on the part of the Chinese pilot) resulted in the emergency landing of the American plane and the crash of the Chinese fighter plane. The emergency landing occurred on the Chinese island of Hainan, the crew of the plane was taken by the Chinese, and the plane itself, or what was left of it after the actions of the crew, remained dismantled into components. The new US president sought to reach understandings with China’s long-time president Jiang Zemin and to try to retrieve the crew and the remains of the plane. In this way, a US-Chinese dialogue began with the US in an inferior position.

Shortly afterward, after understandings were reached, Beijing was declared the host city of the 2008 Olympics, and the discussions regarding China’s joining of the World Trade Organization (WTO) gained momentum. Though Bush the candidate sought to constrain China, by the beginning of his presidential term, the PRC’s standing only continued to rise (Blanchard & Chen, 2015). This was the context immediately prior to the 9/11 attacks. The United States then needed maximum support from the international arena if it wanted to take action, and certainly from the UN Security Council, of which the PRC was a permanent member with veto rights since 1971. In this way, the approach of “China as a strategic competitor” made way for the approach of “China as a partner” by means of the War on Terror, whether in rhetoric (primarily) or in practice, for most of the first decade of the twenty-first century.

American attention shifted to other places, and East Asia was less the focus. During this period, China could also increase its regional influence via regional organizations that China itself had played a role in establishing (such as via the development of the SCO—the Shanghai Cooperation Organization), or through instruments which the United States itself encouraged, such as the Six Party Talks with North Korea, from 2003. Moreover, the more the United States became militarily and economically entangled in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the more China could increase its involvement elsewhere. In the mid-2000s, China began to increasingly invest in many countries, from Sri Lanka to Greece. The world financial crisis of 2008-2009, which harmed the United States and the countries of Europe first and foremost and caused them to be economically drawn into their own domestic matters and to decrease and reduce their capacity for global investment, enabled China, immediately afterward, to significantly increase its investments around the world (Overholt, 2010).

At the same time, between 2000 and 2008, Taiwan was governed by the DPP. The PRC, which at the beginning of the 1990s took action to try to prevent representatives of the KMT from winning the elections, understood that the party that was the main rival of KMT posed an even bigger challenge, as the DPP entertained itself with the idea of full separation from the PRC and non-recognition of the One China principle. As a result, during this period, and particularly during the DPP’s first term in office (2000-2004), an almost total rift emerged between the PRC and Taiwan, and great hostility prevailed between the bodies of government. Nonetheless, during the DPP’s second term in office (2004-2008), the situation changed somewhat, perhaps due to the change of presidents in China (Hu Jintao in place of Jiang Zemin) and perhaps due to a rethinking of more effective means of influencing Taiwan. It was then that the PRC decided to allow greater informal ties with Taiwan and started to cultivate ties with the KMT party, which was then in opposition (Muyard, 2008).

However, at the same time, the hostility between the countries’ governing bodies—the CPC on the one hand, and the DPP on the other—persisted, and at the end of 2004, after the DPP again won the presidential elections, the PRC began to legislate the “Anti-Secession Law of China” (反分裂国家法2005), which was fully enacted in 2005 (following another “white paper” that was published in 2000, again emphasizing its principles and condemning Lee Teng-hui and the “separatists” on the Taiwanese side). This law is ascribed declarative, lobbyist, and diplomatic importance even today, and it includes ten sections. Most of the law’s sections (1-7) contain principled statements on the following themes: “in the whole world, there is only One China” (世界上只有一个中国), that includes mainland China and Taiwan; sovereignty in that One China is indivisible; and actualizing the unification between the PRC and Taiwan is “the sacred task of the entire Chinese People” (全中国人民的神圣职责). This part of the law calls for “the unification of the homeland through peaceful measures” (以和平方式实现祖国统一) and details the different ways of strengthening the connection between mainland China and the island of Taiwan, as well as of conducting negotiations regarding the desired unification.

The two following sections of the law (8 and 9; section 10 only defines the law’s immediate application), on the other hand, address a situation in which unification through peaceful measures is not achieved. The law defines three options in which the state, the PRC, must use non-peaceful measures to “defend the sovereignty of the state and its territorial wholeness” (捍卫国家主权和领土完整): if the forces of “independent Taiwan” (台独) somehow manage to make it so that the division of China is an established fact; if the occurrence of a significant event leads to such a division; or if all possibility of bringing about unification through peaceful measures is lost. The law defines the institutions entrusted with implementing “non-peaceful measures” and seeks to ensure that if such an event occurs, the state would put its greatest efforts into protecting the lives, property, and rights of the people living in Taiwan—Taiwanese and foreigners alike.

This law sparked protest in Taiwan itself on the part of all political parties. However, as already noted, the PRC also promoted informal ties with Taiwan, so when the KMT won the elections of 2008, these ties developed into much more widely ranging relations between PRC and Taiwan. The new KMT president, Ma Ying-jeou, cultivated and advanced China-Taiwan relations according to the tripartite principle: “without unification, without independence, and without the use of force”—in other words, preserving the political status quo while promoting all other connections. Indeed, the scope of trade increased, China also invested in Taiwan (and Taiwanese investments were made in China), tourists began to move between the island and the mainland, and many thousands of PRC citizens settled in Taiwan, and vice-versa. The connections were not only economic, commercial, and related to tourism, but also included deeper ties, based, for example, on shared religions, journeys of pilgrimage, and the support for temples, especially Daoist or Buddhist temples on both sides of the Strait (Brown & Cheng, 2012; Laliberté, 2013).

Relations appeared to be advancing on a clear and positive track, despite the fierce PRC opposition to agreements on the sale of billions of dollars of arms by the United States to Taiwan that emerged from time to time. Meetings between formal PRC and Taiwanese officials occurred on several occasions; the high point was a meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou in Singapore in 2015 and the establishment of mechanisms for direct ties between the governments (Hsiao, 2016).

At the same time, President Obama’s entry into the White House in 2009, and the US initiative that positioned Asia, and especially East Asia, at the focus of its foreign policy (“pivot to Asia”) beginning in the early 2010s, resulted also in a rethinking of US-Taiwan relations. Whereas the Obama Administration continued to accept the One China policy and to support increasingly close relations between the two sides of the Strait, an internal American debate developed on the subject: on the one hand, some maintained that Taiwan had become a factor disturbing the advancement of China-US relations, and at that stage—more than 20 years after the end of the Cold War and 30 years after the normalization of relations with the PRC—there was no longer anything to be gained from US protection of Taiwan. From their perspective, the United States needed to stop selling arms to Taiwan and to promote the position of the PRC to conclude the matter. In contrast, the majority in the United States argued the opposite: that the rise and growing strength of the PRC made it increasingly necessary to promote Taiwan, especially as its increasingly close relations with PRC had made Taiwan more and more dependent on the PRC. Obama, as noted, continued the approach that maintained all the United States’ previous agreements with China on the political level (“One China” and support of ties between China and Taiwan). But at the same time, his administration also promoted wide-scale arms sales to Taiwan worth billions of dollars, including an agreement to upgrade the F-16 fighter planes that had been sold to Taiwan at the beginning of the 1990s and warships (Thayer, 2011). It also attempted to promote the international standing of Taiwan, for example, by adding it to the World Health Organization as an observer in 2009 and, several years later, as an observer in the International Civil Aviation Organization. The Taiwanese also received a visa exemption for entry to the US. The PRC was of course displeased with the way in which the United States had acted. It viewed the arms deals as a deviation from the agreements between the United States and the PRC that had been made decades earlier (under the Reagan Administration, for example, the United States committed itself to reducing such deals over the years) (Löfflmann, 2016). But, in any event, the good relationship between the Chinese administration and the Ma Ying-jeou administration in Taiwan resulted in China-Taiwan relations that continued to advance quickly in positive directions.

However, due to the increasingly close ties and the agreements that developed between the two sides of the Strait, most of the Taiwanese public felt that its own interests were being abandoned, or that the relations between the PRC and Taiwan were improving at the expense of the Taiwanese population. One of the most well-known agreements that Taiwan signed with the PRC, but that Taiwan ultimately did not ratify, was the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement. This agreement was signed in Shanghai in June 2013 and was supposed to be ratified by the legislative branch in Taiwan immediately afterward. However, this agreement, which was to result in a marked intensification of economic and social ties between the two (from banking to health, tourism, etc.), was perceived by the Taiwanese public as extremely problematic and undermining its very existence. Many thought that the agreement would worsen Taiwan’s economic situation, result in total dependence on the PRC, and give it immense influence on the island’s political system. As a result, not only was the agreement itself not ratified, but massive demonstrations and protests, referred to as the “sunflower protests,” led to an overall decline in the popularity of the administration (Templeman et al., 2020).

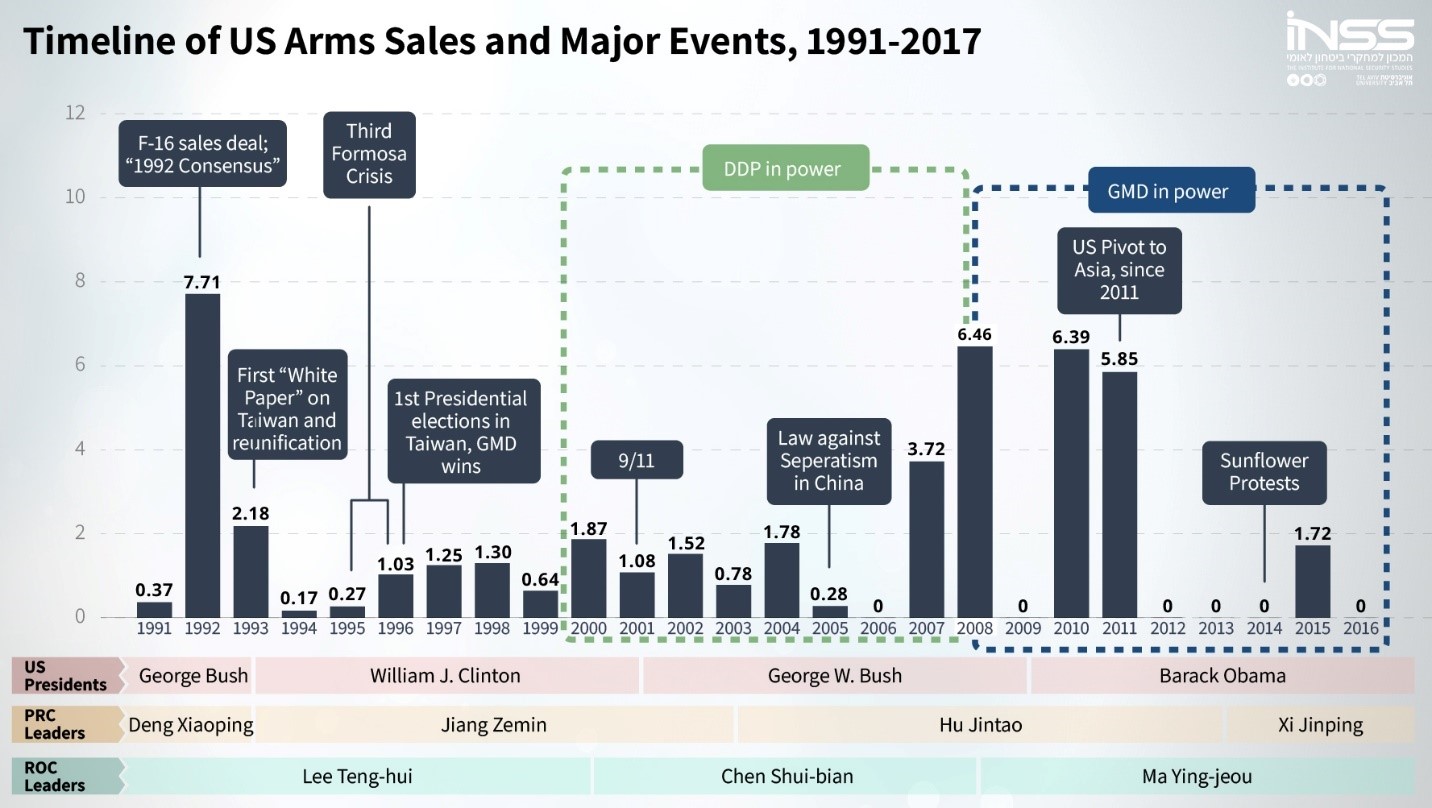

Diagram 1. Timeline – Major events and American announcements of arms sales to Taiwan | Design: Shai Librovsky | Source: Taiwan arms sales, 2023; Major arms sales, n.d.; Taiwan: Major U.S. arms sales since 1990, 2014.

Economic issues were not the only ones to cast a shadow over the question of unification between Taiwan and the PRC; an issue that was no less complex was that of Taiwanese identity, which also lurked in the background. If, for most of its years in existence until the mid-2010s a majority of Taiwan’s population saw themselves and defined themselves as Chinese, the trend over the past three decades has been one of retreat from this definition and a marked increase among those who regard themselves as Taiwanese. The rise of Taiwanese identity has also resulted in hesitations about returning to the homeland, which gradually came to be considered less and less as a true homeland, even if a variety of significant Chinese elements (cultural, religious, etc.) still remained the basis of the new Taiwanese identity (Brown, 2010; Lin, 2016; Liu & Li, 2017).[3]

Conclusion: Major Trends in Relations up to 2016

We can identify three major phases in the relationship between Taiwan and the PRC between 1949 and 2016:

- 1949-1971: After initial attempts at the beginning of the 1950s to achieve military successes that would allow the unification of “China,” both countries understood that it could not be achieved by force, which resulted in stagnated relations. During this period, each tried to exert influence on the other, using both propaganda and military scare tactics, and in this way to produce long-term internal change that would lead to unification. At the same time, from a political perspective, Taiwan’s claim to be the authentic representative of “China” received international legitimacy, including in the UN Security Council based on American support, whereas China and the Soviet Union became enemies.

- 1971-1995: As a result of the process of reconciliation between the United States and China, based on acceptance of the “One China policy” (as opposed to the “One China principle,” which is espoused by the PRC) and in the context of the Cold War, Taiwan’s international legitimacy was eroded, certainly on a formal level (as the PRC replaced Taiwan in UN institutions and received broad international recognition). In this way, reliance on the United States became even more important, while Taiwan’s (global) importance in the technological context (the “silicon shield”) grew. In addition, China and Taiwan gradually began secret discussions to promote mutual ties, in the shadow of the dispute, until they reached a dead end with the third Formosa crisis, which also emphasized Taiwan’s dependence on the United States, the obstructions blocking the PRC, internal politics in the United States, and the PRC’s need to seek a different direction.

- 1995-2016: Despite the military actions of the PRC in the mid-1990s (the third Formosa crisis), two trends emerged from the end of the military crisis. On the one hand, particularly from the mid-2000s onward, we observe a gradual strengthening of the economic and civic ties between the countries. On the other hand, the more pressure was exerted by China on Taiwan to accept its position, the more the Taiwanese public distanced itself from China and from any willingness to discuss unification. The positive contacts between the PRC and the KMT resulted in a public counter-response in Taiwan, after which the DPP rose to power. The United States has remained an essential force for Taiwan, and China understood that, at the time, it was still far from advancing a military force with capabilities superior to the United States. Nonetheless, it has continued to build up its military. From China’s perspective, America’s “pivot to Asia” has brought into sharper relief the US’s intention to engage in what China regards as excessive intervention in its backyard. As a result, its perceived need to build up its forces has only increased.

During the first two phases, the more democratic Taiwan became, the more significant domestic issues and Taiwanese public opinion became in the tripartite relationship. The strengthening of the economic ties between China and Taiwan has helped the island’s economy, but it also brought about an element of dependence on China. The strengthening of ties in the areas of tourism and culture (people-to-people) helped the two populations get to know one another again. At the same time, however, it created channels for potential Chinese campaigns of influence. The more invested the United States became in the Middle East (“the global war on terror”), the greater potential China saw for non-military successes in the context of Taiwan. Still, the Obama Administration’s focus on East Asia (pivot to Asia) caused China to attempt to accelerate its measures vis-à-vis Taiwan under the KMT administration, which accepted some of China’s basic assumptions. This acceleration of the aggressive elements of China’s approach caused the Taiwanese public—as in the third Formosa crisis, even if not in a military sense—to experience intensified fear of China, to emphasize its separate identity, and to form an administration perceived as oppositional to Beijing in the elections of early 2016. After the elections and the DPP’s entry into government, just before Trump’s rise to power in the United States, these elements prompted the Chinese administration, led since 2012 by President Xi Jinping, to change its approach to Taiwan. This change would later gain significant momentum and greatly intensify.

The radicalization of American rhetoric against China—during and following Trump’s election campaign, which intertwined with the “trade war” and the strategic and technological competition between China and the United States at the end of the second decade of the current century—was in a dialectical relationship with similar Chinese radicalization (of course, from the other direction), and China began to position itself, also for its own reasons, as more dominant and aggressive in its foreign policy (“wolf warrior diplomacy,” broad military exercises, intensified activity in the South China Sea, and, though somewhat less, in the East China Sea, meaning near Taiwan, until 2020). Taiwan, therefore, has served as fertile ground, and perhaps an excuse, for both superpowers to spar with one another, even as the economic and civic relations between Taiwan and China continued to develop. Still, domestic Taiwanese issues during Tsai Ing-wen’s first term in office made it seem as if she would lose the presidential elections in January 2020 and the KMT would return to power. However, China’s aggressive approach to the protests in Hong Kong (2019) resulted in a significant rise in the popularity of the DPP, in reaction to the idea that China and Taiwan could be unified based on the Hong Kong model. Indeed, in the 2020 elections, Tsai Ing-wen emerged victorious and continued to serve in office, placing an emphasis on strengthening Taiwan’s relations with the United States.

Concurrently, the Coronavirus pandemic, which created internal problems for both superpowers, intensified the negative trends between China and the United States that had started earlier. In addition to the efforts of Taiwan, which contended with the pandemic successfully, to leverage its strengths to receive a more prominent voice in the global arena, it became apparent that the Taiwan arena was heating up. The penetration of Taiwanese airspace by the Chinese Airforce, including crossing the “median line,” became part of a threat diplomacy that only worsened over time, especially since the autumn of 2020.

A more complex relationship between China and the United States since President Biden came into office, both in terms of intensified technological warfare between the two and the creation of wider American alliance systems in the Indo-Pacific (directly related to the Taiwan issue) has again brought Taiwan, sometimes willingly and typically unwillingly, to the center of the discussion, certainly as long as the matters pertain to semiconductors. The internal political needs of the superpowers have also played an important role, as in the case of the US midterm elections in the autumn of 2022, which occurred around the time of the visit of Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan and resulted in a harsh Chinese response; or the 20th National Congress of the CPC (October 2022), which combined to engender a firmer hand (or harsher rhetoric) on the part of the Chinese regime. All of these factors interacted with global geopolitical issues such as the war in Ukraine, which also helped radicalize the discourse, and the reactions within the tripartite relations between China, Taiwan, and the United States.

In practice, we can say that the situation since Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan constitutes a “fourth Formosa crisis,” which has continued far into 2024 (and continues at the time of writing) and can also be identified in the Chinese response to the Taiwanese elections at the beginning of 2024 and to the inauguration speech of the new president William Lai, also from the DPP, in May 2024. This ongoing crisis itself, whose more recent causes lie in the 2016 fault line, requires separate extensive examination.

Bibliography

Adisson, C. (2000, September 29). A silicon shield protects Taiwan. The New York Times. https://tinyurl.com/68b3vzmf

-. (2001, May 12). ‘Silicon shield’ may protect from China attack. Taipei Times. https://tinyurl.com/ms5z883x

Aldrich, R.J, Rawnsley, G.D, & Rawnsley, M.T. (Eds.) (2000). The clandestine cold war in Asia, 1945-6: Western intelligence, propaganda, security and special operations. Frank Cass.

An, J. (2013). Mao Zedong’s “Three Worlds” theory: Political considerations and value for the times. Social Sciences in China, 34(1), 35–57. DOI:10.1080/02529203.2013.760715

Andrade, T. (2008). How Taiwan became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han colonization in the seventeenth century. Columbia University Press.

Baum R. (2001). From “strategic partners” to “strategic competitors”: George W. Bush and the politics of U.S. China policy. Journal of East Asian Studies, 1(2),191-220. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1598240800000497

Blanchard, J.F., & Shen, S. (2015). Conflict and cooperation in Sino-US relations: Change and continuity, causes and cures. Routledge.

Brown, D.A., & Cheng, T.J. (2012). Religious relations across the Taiwan Strait: Patterns, alignments, and political effects. Orbis, 56(1), 60-81.

Brown, M. (2010). Changing authentic identities: Evidence from Taiwan and China. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 16(3), 459-479. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40926117

Chen, Y.L. (2024). From Laissez Faire to a market mechanism: The formation of housing finance in Taiwan. International Journal of Taiwan Studies (published online ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1163/24688800-20241374

Chen Z. (2019). 九五四年至一九五八年间中共对台策略的调整探析 [Analysis of the CCP’s changing policy towards Taiwan between 1954-1958]. Zhonggong dang yanjiu, 7, 36-50.

Drun, J. (2017, December 28). One China, multiple interpretations. Center for Advanced China Research. https://tinyurl.com/s76patkp

Election Study Center, National Chengchi University. https://tinyurl.com/u6e4xku3

Fan, Y. (1997).美国“以台制华”政策的制约因素及前景 [Conditions, elements, and perspectives of the American ‘use Taiwan to control China’ policy], Taiwan Yanjiu 3, 37-42.

Fang, L., & Zhao, K. (2021). 国家核心利益与中国新外交 [National Core Interests and China’s New Diplomacy]. Guoji zhengzhi kexue, 6(3), 68-94. https://tinyurl.com/3sr577xx

Foot, R. (2000). Rights beyond borders: The global community and the struggle over human rights in China. Oxford University Press.

Goldstein, S.M., & Schriver, R. (2001). An uncertain relationship: The United States, Taiwan and the Taiwan Relations Act. The China Quarterly, 165,147-172. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0009443901000080

Goldstein, S.M. (2023, August 31). Understanding the One China policy. Brookings. https://tinyurl.com/yedesvtm

Hsiao, F.S.T., & Sullivan, L.R. (1979). The Chinese communist party and the status of Taiwan, 1928-1943. Pacific Affairs, 52(3), 446–467. DOI:10.2307/2757657

Hsiao, H.H.M. (2016). 2016 Taiwan elections: Significance and implications. Orbis, 60(4), 504-514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2016.08.006

Jacobs, J.B. (2012). Democratizing Taiwan. Brill.

Joint statement following discussions with leaders of the People’s Republic of China (Shanghai Communiqué). (1972, February 27). US Department of State, Office of the Historians. https://tinyurl.com/4tv4rsxf

Kan, S.A. (2009, August 17). China/Taiwan: Evolution of the “One China” policy—key statements from Washington, Beijing, and Taipei. Congressional Research Service. https://tinyurl.com/nm5ahajp

-. (2014, August 29). Taiwan: Major U.S. arms sales since 1990. Congressional Research Service. https://tinyurl.com/dpzprtx7

Kanwal, G. (2007). China’s new war concepts for 21st century battlefields. Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, 48, 1-5. https://tinyurl.com/4ya5tefv

Kuo, S.W.Y. (1983). The Taiwan economy in transition. Westview Press.

Laliberté, A. (2013). The growth of a Taiwanese Buddhist association in China: Soft power and institutional learning. China Information, 27(1), 81-105.

Lee, T.C. (1993). Perspectives on US sales of F‐16 to Taiwan. The Journal of Contemporary China, 2(2), 87-92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670569308724167

Liao, P., & Wang, D. (2006). Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule, 1895–1945: History, culture, memory. Columbia University Press.

Lin, S.S. (2016). Taiwan’s China dilemma: Contested identities and multiple interests in Taiwan’s cross-strait economic policy. Stanford University Press.

Liu, F.C.S., & Li, Y. (2017). Generation matters: Taiwan’s perceptions of mainland China and attitudes towards cross-strait trade talks, Journal of Contemporary China, 26(104), 263-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2016.1223107

Löfflmann, G. (2016). The pivot between containment, engagement, and restraint: President Obama’s conflicted grand strategy in Asia. Asian Security, 12(2), 92-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2016.1190338

Major arms sales (n.d.). Defense Security Cooperation Agency. https://tinyurl.com/yndyk9vy

Mizuno, N. (2009). Early Meiji policies towards the Ryukyus and the Taiwanese Aboriginal territories. Modern Asian Studies, 43(3), 683-739. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X07003034

Murray, J.A. (2017). China’s lonely revolution: The local communist movement of Hainan Island, 1926-1956. State University of New York Press.

Mutual defense treaty between the United States and the Republic of China. (1954, December 2). The Avalon Project. https://tinyurl.com/hyzptmza

Muyard, F. (2008). Taiwan elections 2008: Ma Ying-jeou’s victory and the KMT’s return to power. China Perspectives, 1, 79-94. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.3423

Nam, K.K. (2020). US strategy and role in cross-strait relations: Focusing on US-Taiwan relations. The Journal of East Asian Affairs, 33(1), 155-176. https://tinyurl.com/34sz2e7b

Overholt, W.H. (2010). China in the global financial crisis: Rising influence, rising challenges. The Washington Quarterly, 33(1), 21-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/01636600903418652

Ross, R.S. (2000). The 1995-96 Taiwan Strait confrontation: Coercion, credibility, and the use of force. International Security, 25(2), 87-123. https://doi.org/10.1162/016228800560462

Shambaugh, D. (2000). Sino-American strategic relations: From partners to competitors. Survival, 42(1), 97-115. https://doi.org/10.1080/713660152

State Council (1993, August 31). The Taiwan question and “reunification” of China. CSIS Interpret: China, original work published in Xinhua News Agency. https://tinyurl.com/sek48ut2

Taiwan arms sales notified to congress 1990-2023 (2023, December 15). Taiwan Defense & National Security. https://tinyurl.com/3s6c2abj

Templeman, K., Chu, Y. & Diamond, L. (eds.) (2020). Dynamics of democracy in Taiwan: The Ma Ying-jeou years. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Thayer, C. (2011, October 4). US arms sales to Taiwan: Impact on Sino-American relations. EastAsiaForum. https://tinyurl.com/mr3kx9uv

Thies, W.J., & Bratton, P.C. (2004). When governments collide in the Taiwan Strait. Journal of Strategic studies, 27(4), 556-584. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362369042000314510

Trent, M. (2020). Over the Line: The implications of China’s ADIZ intrusions in Northeast Asia. Federation of American Scientists. https://tinyurl.com/mr2wm3ru